User login

Since my high school days, I have used some form of artificial sweetener in lieu of sugar. Long believing that sugar avoidance was the key to weight maintenance, I didn’t give much thought to the published ill effects of sugar substitutes—after all, I wasn’t a mouse, and I wasn’t consuming mass doses. Did the artificial sweeteners assist in controlling my weight? Quite honestly, I doubt it—but I was so used to being “sugar free” that I was habituated to using these products.

Several years ago at a luncheon, I was reaching for a packet of artificial sweetener to pour into my iced tea when an NP friend stopped me. She and her husband (a pharmacist) had sworn off these products after noting that he was having issues with his cognition and experiencing increased irritability. With no obvious cause for these symptoms, they investigated his diet. He had, over the previous year, increased his use of aspartame. They found research supporting an association between aspartame and changes in behavior and cognition. When he stopped using the product, they both noticed a return to his former jovial, intellectual self. I acknowledged their research conclusion as an “n = 1” but gave it no further credence.

More recently, friends who had adopted an “all-natural” diet chastised me for drinking sugar-free seltzer. I had switched years ago from diet sodas to this beverage as my primary source of hydration. What could be wrong? It had zero calories, no sodium, and no sugar. Ah, but it contained aspartame! Since switching to a food plan without aspartame, my friends had observed that they were feeling better and more alert. Hmm, sounded familiar … maybe there was something to these claims after all. I did a little research of my own, and was I surprised!

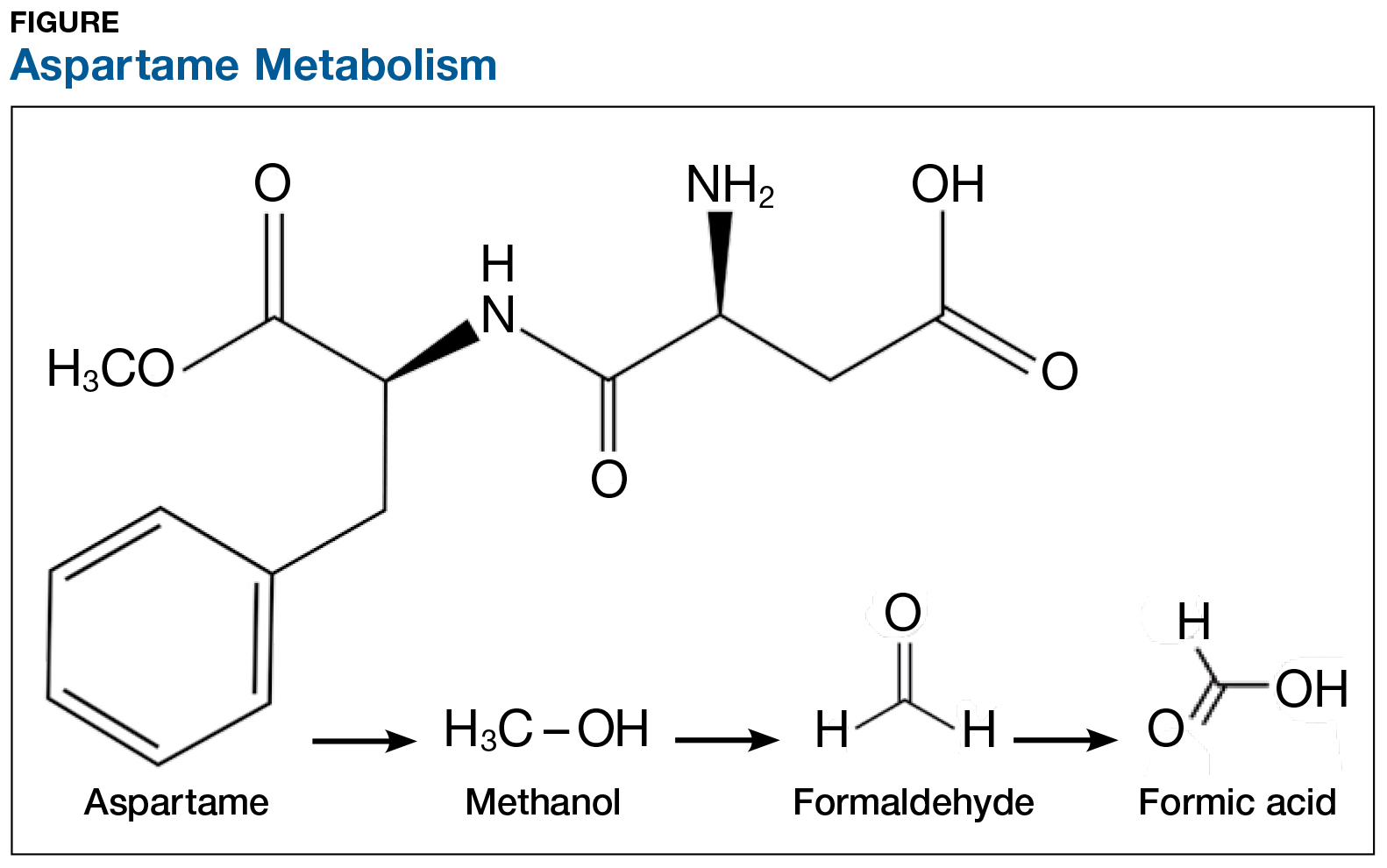

On the exterior, aspartame is a highly studied food additive with decades of research demonstrating its safety for human consumption.1 But what exactly happens when this sweetener is ingested? First, aspartame breaks down into amino acids and methanol (ie, wood alcohol). The methanol continues to break down into formaldehyde and formic acid, a substance commonly found in bee and ant venom (see Figure). And if that weren’t enough, a potential brain tumor agent (aspartylphenylalanine diketopiperazine) is also a residual byproduct.2,3 As you might expect, these components and byproducts come with varying adverse effects and potential health risks.

The majority of artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) contain aspartame. As early as 1984—a mere six months after aspartame was approved for use in soft drinks—the FDA, with the assistance of the CDC, undertook an investigation of consumer complaints related to its use. The research team interviewed 517 complainants; 346 (67%) reported neurologic/behavioral symptoms, including headache, dizziness, and mood alteration.4 Despite that statistic, however, the researchers reported no evidence for the existence of serious, widespread, adverse health consequences resulting from aspartame consumption.4

Reading these reports reminded me of my friends’ comments and strongly suggested to me that soft drinks containing aspartame may be hard on the brain. Further to this point, a recent study found that ASB consumption is associated with an increased risk for stroke and dementia.5

Additional studies—including evaluations of possible associations between aspartame and headaches, seizures, behavior, cognition, and mood, as well as allergic-type reactions and use by potentially sensitive subpopulations—have been conducted. The verdict? Scientists maintain that aspartame is safe and that there are no unresolved questions regarding its safety when used as intended.6 Some researchers question the validity of the link between ASB consumption and negative health consequences, suggesting that individuals in worse health consume diet beverages in an effort to slow health deterioration or to lose weight.7 Yet, the debate about the effects of aspartame on our organs continues.

The number of epidemiologic studies that document strong associations between frequent ASB consumption and illness suggests that substituting or promoting artificial sweeteners as “healthy alternatives” to sugar may not be advisable.8 In fact, the most recent studies indicate that artificial sweeteners—the very compounds marketed to assist with weight control—can lead to weight gain, as they trick our brains into craving high-calorie foods. Moreover, ASB consumption is associated with a 21% increased risk for type 2 diabetes.9 Azad and colleagues found that evidence does not clearly support the use of nonnutritive sweeteners for weight management; they recommend using caution with these products until the long-term risks and benefits are fully understood.7

Is satisfying your sweet tooth with sugar alternatives worth the potential risk? Most of the studies conducted to support or refute aspartame-related health concerns prove correlation, not causality. A purist might point out that many of the studies have limitations that can lead to faulty conclusions. Be that as it may, it still gives one pause.

Small doses of aspartame each day might not be a tipping point toward the documented health complaints, but the consistent concerns about its effects were enough for me to make the switch to plain water, and sugar for my coffee. I do believe that Mary Poppins was correct—a spoonful of sugar does help—and I, for one, am following her lead.

What do you think? Are these concerns unfounded, or are we sweetening our road to poor health? Share your thoughts with me at NPeditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

1. Novella S. Aspartame: truth vs. fiction. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/aspartame-truth-vs-fiction/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

2. Barua J, Bal A. Emerging facts about aspartame. www.manningsscience.com/uploads/8/6/8/1/8681125/article-on-aspartame.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. Supersweet blog. Learning about sweeteners. https://supersweetblog.wordpress.com/aspartame/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

4. CDC. Evaluation of consumer complaints related to aspartame use. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1984;33(43):605-607.

5. Pase MP, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Sugar- and artificially sweetened beverages and the risks of incident stroke and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48(5): 1139-1146.

6. Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, et al. Aspartame: review of safety. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;35(2):S1- S93.

7. Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, Chauhan BF, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ. 2017;189(28): E929-E939.

8. Wersching H, Gardener H, Sacco L. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages in relation to stroke and dementia. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1129-1131.

9. Huang M, Quddus A, Stinson L, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, plain water, and incident diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the prospective Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:614-622.

Since my high school days, I have used some form of artificial sweetener in lieu of sugar. Long believing that sugar avoidance was the key to weight maintenance, I didn’t give much thought to the published ill effects of sugar substitutes—after all, I wasn’t a mouse, and I wasn’t consuming mass doses. Did the artificial sweeteners assist in controlling my weight? Quite honestly, I doubt it—but I was so used to being “sugar free” that I was habituated to using these products.

Several years ago at a luncheon, I was reaching for a packet of artificial sweetener to pour into my iced tea when an NP friend stopped me. She and her husband (a pharmacist) had sworn off these products after noting that he was having issues with his cognition and experiencing increased irritability. With no obvious cause for these symptoms, they investigated his diet. He had, over the previous year, increased his use of aspartame. They found research supporting an association between aspartame and changes in behavior and cognition. When he stopped using the product, they both noticed a return to his former jovial, intellectual self. I acknowledged their research conclusion as an “n = 1” but gave it no further credence.

More recently, friends who had adopted an “all-natural” diet chastised me for drinking sugar-free seltzer. I had switched years ago from diet sodas to this beverage as my primary source of hydration. What could be wrong? It had zero calories, no sodium, and no sugar. Ah, but it contained aspartame! Since switching to a food plan without aspartame, my friends had observed that they were feeling better and more alert. Hmm, sounded familiar … maybe there was something to these claims after all. I did a little research of my own, and was I surprised!

On the exterior, aspartame is a highly studied food additive with decades of research demonstrating its safety for human consumption.1 But what exactly happens when this sweetener is ingested? First, aspartame breaks down into amino acids and methanol (ie, wood alcohol). The methanol continues to break down into formaldehyde and formic acid, a substance commonly found in bee and ant venom (see Figure). And if that weren’t enough, a potential brain tumor agent (aspartylphenylalanine diketopiperazine) is also a residual byproduct.2,3 As you might expect, these components and byproducts come with varying adverse effects and potential health risks.

The majority of artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) contain aspartame. As early as 1984—a mere six months after aspartame was approved for use in soft drinks—the FDA, with the assistance of the CDC, undertook an investigation of consumer complaints related to its use. The research team interviewed 517 complainants; 346 (67%) reported neurologic/behavioral symptoms, including headache, dizziness, and mood alteration.4 Despite that statistic, however, the researchers reported no evidence for the existence of serious, widespread, adverse health consequences resulting from aspartame consumption.4

Reading these reports reminded me of my friends’ comments and strongly suggested to me that soft drinks containing aspartame may be hard on the brain. Further to this point, a recent study found that ASB consumption is associated with an increased risk for stroke and dementia.5

Additional studies—including evaluations of possible associations between aspartame and headaches, seizures, behavior, cognition, and mood, as well as allergic-type reactions and use by potentially sensitive subpopulations—have been conducted. The verdict? Scientists maintain that aspartame is safe and that there are no unresolved questions regarding its safety when used as intended.6 Some researchers question the validity of the link between ASB consumption and negative health consequences, suggesting that individuals in worse health consume diet beverages in an effort to slow health deterioration or to lose weight.7 Yet, the debate about the effects of aspartame on our organs continues.

The number of epidemiologic studies that document strong associations between frequent ASB consumption and illness suggests that substituting or promoting artificial sweeteners as “healthy alternatives” to sugar may not be advisable.8 In fact, the most recent studies indicate that artificial sweeteners—the very compounds marketed to assist with weight control—can lead to weight gain, as they trick our brains into craving high-calorie foods. Moreover, ASB consumption is associated with a 21% increased risk for type 2 diabetes.9 Azad and colleagues found that evidence does not clearly support the use of nonnutritive sweeteners for weight management; they recommend using caution with these products until the long-term risks and benefits are fully understood.7

Is satisfying your sweet tooth with sugar alternatives worth the potential risk? Most of the studies conducted to support or refute aspartame-related health concerns prove correlation, not causality. A purist might point out that many of the studies have limitations that can lead to faulty conclusions. Be that as it may, it still gives one pause.

Small doses of aspartame each day might not be a tipping point toward the documented health complaints, but the consistent concerns about its effects were enough for me to make the switch to plain water, and sugar for my coffee. I do believe that Mary Poppins was correct—a spoonful of sugar does help—and I, for one, am following her lead.

What do you think? Are these concerns unfounded, or are we sweetening our road to poor health? Share your thoughts with me at NPeditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

Since my high school days, I have used some form of artificial sweetener in lieu of sugar. Long believing that sugar avoidance was the key to weight maintenance, I didn’t give much thought to the published ill effects of sugar substitutes—after all, I wasn’t a mouse, and I wasn’t consuming mass doses. Did the artificial sweeteners assist in controlling my weight? Quite honestly, I doubt it—but I was so used to being “sugar free” that I was habituated to using these products.

Several years ago at a luncheon, I was reaching for a packet of artificial sweetener to pour into my iced tea when an NP friend stopped me. She and her husband (a pharmacist) had sworn off these products after noting that he was having issues with his cognition and experiencing increased irritability. With no obvious cause for these symptoms, they investigated his diet. He had, over the previous year, increased his use of aspartame. They found research supporting an association between aspartame and changes in behavior and cognition. When he stopped using the product, they both noticed a return to his former jovial, intellectual self. I acknowledged their research conclusion as an “n = 1” but gave it no further credence.

More recently, friends who had adopted an “all-natural” diet chastised me for drinking sugar-free seltzer. I had switched years ago from diet sodas to this beverage as my primary source of hydration. What could be wrong? It had zero calories, no sodium, and no sugar. Ah, but it contained aspartame! Since switching to a food plan without aspartame, my friends had observed that they were feeling better and more alert. Hmm, sounded familiar … maybe there was something to these claims after all. I did a little research of my own, and was I surprised!

On the exterior, aspartame is a highly studied food additive with decades of research demonstrating its safety for human consumption.1 But what exactly happens when this sweetener is ingested? First, aspartame breaks down into amino acids and methanol (ie, wood alcohol). The methanol continues to break down into formaldehyde and formic acid, a substance commonly found in bee and ant venom (see Figure). And if that weren’t enough, a potential brain tumor agent (aspartylphenylalanine diketopiperazine) is also a residual byproduct.2,3 As you might expect, these components and byproducts come with varying adverse effects and potential health risks.

The majority of artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) contain aspartame. As early as 1984—a mere six months after aspartame was approved for use in soft drinks—the FDA, with the assistance of the CDC, undertook an investigation of consumer complaints related to its use. The research team interviewed 517 complainants; 346 (67%) reported neurologic/behavioral symptoms, including headache, dizziness, and mood alteration.4 Despite that statistic, however, the researchers reported no evidence for the existence of serious, widespread, adverse health consequences resulting from aspartame consumption.4

Reading these reports reminded me of my friends’ comments and strongly suggested to me that soft drinks containing aspartame may be hard on the brain. Further to this point, a recent study found that ASB consumption is associated with an increased risk for stroke and dementia.5

Additional studies—including evaluations of possible associations between aspartame and headaches, seizures, behavior, cognition, and mood, as well as allergic-type reactions and use by potentially sensitive subpopulations—have been conducted. The verdict? Scientists maintain that aspartame is safe and that there are no unresolved questions regarding its safety when used as intended.6 Some researchers question the validity of the link between ASB consumption and negative health consequences, suggesting that individuals in worse health consume diet beverages in an effort to slow health deterioration or to lose weight.7 Yet, the debate about the effects of aspartame on our organs continues.

The number of epidemiologic studies that document strong associations between frequent ASB consumption and illness suggests that substituting or promoting artificial sweeteners as “healthy alternatives” to sugar may not be advisable.8 In fact, the most recent studies indicate that artificial sweeteners—the very compounds marketed to assist with weight control—can lead to weight gain, as they trick our brains into craving high-calorie foods. Moreover, ASB consumption is associated with a 21% increased risk for type 2 diabetes.9 Azad and colleagues found that evidence does not clearly support the use of nonnutritive sweeteners for weight management; they recommend using caution with these products until the long-term risks and benefits are fully understood.7

Is satisfying your sweet tooth with sugar alternatives worth the potential risk? Most of the studies conducted to support or refute aspartame-related health concerns prove correlation, not causality. A purist might point out that many of the studies have limitations that can lead to faulty conclusions. Be that as it may, it still gives one pause.

Small doses of aspartame each day might not be a tipping point toward the documented health complaints, but the consistent concerns about its effects were enough for me to make the switch to plain water, and sugar for my coffee. I do believe that Mary Poppins was correct—a spoonful of sugar does help—and I, for one, am following her lead.

What do you think? Are these concerns unfounded, or are we sweetening our road to poor health? Share your thoughts with me at NPeditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

1. Novella S. Aspartame: truth vs. fiction. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/aspartame-truth-vs-fiction/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

2. Barua J, Bal A. Emerging facts about aspartame. www.manningsscience.com/uploads/8/6/8/1/8681125/article-on-aspartame.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. Supersweet blog. Learning about sweeteners. https://supersweetblog.wordpress.com/aspartame/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

4. CDC. Evaluation of consumer complaints related to aspartame use. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1984;33(43):605-607.

5. Pase MP, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Sugar- and artificially sweetened beverages and the risks of incident stroke and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48(5): 1139-1146.

6. Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, et al. Aspartame: review of safety. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;35(2):S1- S93.

7. Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, Chauhan BF, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ. 2017;189(28): E929-E939.

8. Wersching H, Gardener H, Sacco L. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages in relation to stroke and dementia. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1129-1131.

9. Huang M, Quddus A, Stinson L, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, plain water, and incident diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the prospective Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:614-622.

1. Novella S. Aspartame: truth vs. fiction. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/aspartame-truth-vs-fiction/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

2. Barua J, Bal A. Emerging facts about aspartame. www.manningsscience.com/uploads/8/6/8/1/8681125/article-on-aspartame.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. Supersweet blog. Learning about sweeteners. https://supersweetblog.wordpress.com/aspartame/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

4. CDC. Evaluation of consumer complaints related to aspartame use. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1984;33(43):605-607.

5. Pase MP, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Sugar- and artificially sweetened beverages and the risks of incident stroke and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48(5): 1139-1146.

6. Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, et al. Aspartame: review of safety. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;35(2):S1- S93.

7. Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, Chauhan BF, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ. 2017;189(28): E929-E939.

8. Wersching H, Gardener H, Sacco L. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages in relation to stroke and dementia. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1129-1131.

9. Huang M, Quddus A, Stinson L, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, plain water, and incident diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the prospective Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:614-622.