User login

HPV: Changing the Statistics

In the world of research, an “n of 1” is considered an insufficient sample size to make an inference about a population. While distinguishing significance in research is vital in the scientific world, this statistical view often feels invalid when the “n of 1” is you or someone you know. And when the statistic is a diagnosis of cancer, that “1” feels even more noteworthy.

We know that cancer is a devastating disease that results in an increasing number of diagnoses each day. Case in point, the American Cancer Society estimates that more than 4,700 new cancers will be diagnosed each day in 2018.1 Most of us know that breast, colon, lung, and prostate cancer are the main contributors to those staggering numbers. But did you know that the incidence of oropharyngeal cancers (OPCs) is increasing? I didn’t.

It is estimated that 51,540 new cancer cases in 2018 will be of the oral cavity and pharynx and will cause approximately 10,000 deaths in the United States (US).1 Included in this estimate is the increasing incidence of human papillomavirus–associated oropharyngeal cancers (HPV-OPCs). The “n of 1” that started this discussion? That was a colleague of mine, who received just such a diagnosis. And the causative factor was surprising to me.

Now, please don’t misunderstand me—I know that HPV, a group of more than 150 related viruses, is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the US.2 I also know that HPV is implicated in genital warts and in cervical and anal cancers. The virus, which is transmitted through intimate skin-to-skin contact, is acquired by many during their adolescent and young adult years.2 Currently, 84 million Americans have HPV, and 14 million new cases are diagnosed each year.3

The most serious of those health problems, HPV-related cancers (which include cervical, vulvovaginal, anal, and oropharyngeal), are on the rise in the US.4 The prevalence of HPV in oropharyngeal tumors increased from 16.3% during the 1980s to 72.7% during the 2000s.5 Moreover, HPV has been implicated in 12% to 63% of all oropharyngeal cancers.6 Fifteen years ago, researchers concluded that HPV type 16 was the cause of 90% of cases of HPV-positive squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck.7,8 At any given time, 7% of the population between ages 14 and 69 are infected by the virus within the oral mucosa.9

For my colleague—and many of us—the ship of prevention has sailed. But what disconcerts me most about this rise in HPV-related cancers is that, as of 2006, we have a vaccine that protects against infection with the two most prevalent cancer-causing HPV types. And yet, our vaccination rates continue to fall short of the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s goal of having 80% of females ages 13 to 15 fully vaccinated against HPV.10

Continue to: Research has shown that parents of young adolescents...

Research has shown that parents of young adolescents are often upset by the recommendation that their children receive the HPV vaccine.11 Common beliefs are that the vaccine will give adolescents permission to become sexually active—or, conversely, that the adolescent isn’t sexually active, so the vaccine isn’t necessary. The reality of the situation: Adolescents don’t consider oral sex as having sexual relations, and oral sex is often the first sexual encounter for young people. Adolescents also regard oral sex as less risky than vaginal sex.12 So, many have unknowingly put themselves at risk while thinking they are actually being “safe.”

There are ways to reduce cancer risk, but few interventions are more effective than HPV vaccination.13 Given the incidence of HPV-OPC, it’s time to debunk the misbeliefs about sexual activity and move on to a concerted effort to promote HPV vaccination. Recent advertising about the HPV vaccine has emphasized the consequence of cancer in its messages. I applaud this new direction—it could be key to reversing the persistently low rate of HPV vaccination and changing that “n of 1” to zero. Share your trials and triumphs in promoting HPV vaccination with me at NPeditor@mdedge.com.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7-30.

2. CDC. Human papillomavirus (HPV). www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/whatishpv.html. Accessed August 8, 2018.

3. Patel EU, Grabowski MK, Eisenberg AL, et al. Increases in human papillomavirus vaccination among adolescent and young adult males in the United States, 2011-2016. J Infect Dis. 2018;218(1):109-113.

4. Dilley S, Scarinci I, Kimberlin D, Straughn JM. Preventing human papillomavirus-related cancers: we are all in this together. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(6):576.e1-576.e5.

5. Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29(32):4294-4301.

6. Chandrani P, Kulkarni V, Iyer P, et al. NGS-based approach to determine the presence of HPV and their sites of integration in human cancer genome. Br J Cancer. 2015;112 (12):1958-1965.

7. Herrero R, Castellsague X, Pawlita M, et al; IARC Multicenter Oral Cancer Study Group. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(23):1772-1783.

8. Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(9):709-720.

9. Golusin´ski W, Leemans CR, Dietz D, eds. HPV Infection in Head and Neck Cancer. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

10. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Increase the vaccination coverage level of 3 doses of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for females by age 13 to 15 years. www.healthypeople.gov/node/4657/data_details. Accessed August 8, 2018.

11. National Cancer Institute; National Institutes of Health. President’s cancer panel annual report 2012–2013. Accelerating HPV vaccine uptake: urgency for action to prevent cancer. https://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/HPV/index.htm. Accessed August 8, 2018.

12. Halpern-Felsher BL, Cornell JL, Kropp RY, Tschann JM. Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):845-851.

13. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Call to action: HPV vaccination as a public health priority. www.nfid.org/publications/cta/hpv-call-to-action.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2018.

In the world of research, an “n of 1” is considered an insufficient sample size to make an inference about a population. While distinguishing significance in research is vital in the scientific world, this statistical view often feels invalid when the “n of 1” is you or someone you know. And when the statistic is a diagnosis of cancer, that “1” feels even more noteworthy.

We know that cancer is a devastating disease that results in an increasing number of diagnoses each day. Case in point, the American Cancer Society estimates that more than 4,700 new cancers will be diagnosed each day in 2018.1 Most of us know that breast, colon, lung, and prostate cancer are the main contributors to those staggering numbers. But did you know that the incidence of oropharyngeal cancers (OPCs) is increasing? I didn’t.

It is estimated that 51,540 new cancer cases in 2018 will be of the oral cavity and pharynx and will cause approximately 10,000 deaths in the United States (US).1 Included in this estimate is the increasing incidence of human papillomavirus–associated oropharyngeal cancers (HPV-OPCs). The “n of 1” that started this discussion? That was a colleague of mine, who received just such a diagnosis. And the causative factor was surprising to me.

Now, please don’t misunderstand me—I know that HPV, a group of more than 150 related viruses, is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the US.2 I also know that HPV is implicated in genital warts and in cervical and anal cancers. The virus, which is transmitted through intimate skin-to-skin contact, is acquired by many during their adolescent and young adult years.2 Currently, 84 million Americans have HPV, and 14 million new cases are diagnosed each year.3

The most serious of those health problems, HPV-related cancers (which include cervical, vulvovaginal, anal, and oropharyngeal), are on the rise in the US.4 The prevalence of HPV in oropharyngeal tumors increased from 16.3% during the 1980s to 72.7% during the 2000s.5 Moreover, HPV has been implicated in 12% to 63% of all oropharyngeal cancers.6 Fifteen years ago, researchers concluded that HPV type 16 was the cause of 90% of cases of HPV-positive squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck.7,8 At any given time, 7% of the population between ages 14 and 69 are infected by the virus within the oral mucosa.9

For my colleague—and many of us—the ship of prevention has sailed. But what disconcerts me most about this rise in HPV-related cancers is that, as of 2006, we have a vaccine that protects against infection with the two most prevalent cancer-causing HPV types. And yet, our vaccination rates continue to fall short of the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s goal of having 80% of females ages 13 to 15 fully vaccinated against HPV.10

Continue to: Research has shown that parents of young adolescents...

Research has shown that parents of young adolescents are often upset by the recommendation that their children receive the HPV vaccine.11 Common beliefs are that the vaccine will give adolescents permission to become sexually active—or, conversely, that the adolescent isn’t sexually active, so the vaccine isn’t necessary. The reality of the situation: Adolescents don’t consider oral sex as having sexual relations, and oral sex is often the first sexual encounter for young people. Adolescents also regard oral sex as less risky than vaginal sex.12 So, many have unknowingly put themselves at risk while thinking they are actually being “safe.”

There are ways to reduce cancer risk, but few interventions are more effective than HPV vaccination.13 Given the incidence of HPV-OPC, it’s time to debunk the misbeliefs about sexual activity and move on to a concerted effort to promote HPV vaccination. Recent advertising about the HPV vaccine has emphasized the consequence of cancer in its messages. I applaud this new direction—it could be key to reversing the persistently low rate of HPV vaccination and changing that “n of 1” to zero. Share your trials and triumphs in promoting HPV vaccination with me at NPeditor@mdedge.com.

In the world of research, an “n of 1” is considered an insufficient sample size to make an inference about a population. While distinguishing significance in research is vital in the scientific world, this statistical view often feels invalid when the “n of 1” is you or someone you know. And when the statistic is a diagnosis of cancer, that “1” feels even more noteworthy.

We know that cancer is a devastating disease that results in an increasing number of diagnoses each day. Case in point, the American Cancer Society estimates that more than 4,700 new cancers will be diagnosed each day in 2018.1 Most of us know that breast, colon, lung, and prostate cancer are the main contributors to those staggering numbers. But did you know that the incidence of oropharyngeal cancers (OPCs) is increasing? I didn’t.

It is estimated that 51,540 new cancer cases in 2018 will be of the oral cavity and pharynx and will cause approximately 10,000 deaths in the United States (US).1 Included in this estimate is the increasing incidence of human papillomavirus–associated oropharyngeal cancers (HPV-OPCs). The “n of 1” that started this discussion? That was a colleague of mine, who received just such a diagnosis. And the causative factor was surprising to me.

Now, please don’t misunderstand me—I know that HPV, a group of more than 150 related viruses, is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the US.2 I also know that HPV is implicated in genital warts and in cervical and anal cancers. The virus, which is transmitted through intimate skin-to-skin contact, is acquired by many during their adolescent and young adult years.2 Currently, 84 million Americans have HPV, and 14 million new cases are diagnosed each year.3

The most serious of those health problems, HPV-related cancers (which include cervical, vulvovaginal, anal, and oropharyngeal), are on the rise in the US.4 The prevalence of HPV in oropharyngeal tumors increased from 16.3% during the 1980s to 72.7% during the 2000s.5 Moreover, HPV has been implicated in 12% to 63% of all oropharyngeal cancers.6 Fifteen years ago, researchers concluded that HPV type 16 was the cause of 90% of cases of HPV-positive squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck.7,8 At any given time, 7% of the population between ages 14 and 69 are infected by the virus within the oral mucosa.9

For my colleague—and many of us—the ship of prevention has sailed. But what disconcerts me most about this rise in HPV-related cancers is that, as of 2006, we have a vaccine that protects against infection with the two most prevalent cancer-causing HPV types. And yet, our vaccination rates continue to fall short of the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s goal of having 80% of females ages 13 to 15 fully vaccinated against HPV.10

Continue to: Research has shown that parents of young adolescents...

Research has shown that parents of young adolescents are often upset by the recommendation that their children receive the HPV vaccine.11 Common beliefs are that the vaccine will give adolescents permission to become sexually active—or, conversely, that the adolescent isn’t sexually active, so the vaccine isn’t necessary. The reality of the situation: Adolescents don’t consider oral sex as having sexual relations, and oral sex is often the first sexual encounter for young people. Adolescents also regard oral sex as less risky than vaginal sex.12 So, many have unknowingly put themselves at risk while thinking they are actually being “safe.”

There are ways to reduce cancer risk, but few interventions are more effective than HPV vaccination.13 Given the incidence of HPV-OPC, it’s time to debunk the misbeliefs about sexual activity and move on to a concerted effort to promote HPV vaccination. Recent advertising about the HPV vaccine has emphasized the consequence of cancer in its messages. I applaud this new direction—it could be key to reversing the persistently low rate of HPV vaccination and changing that “n of 1” to zero. Share your trials and triumphs in promoting HPV vaccination with me at NPeditor@mdedge.com.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7-30.

2. CDC. Human papillomavirus (HPV). www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/whatishpv.html. Accessed August 8, 2018.

3. Patel EU, Grabowski MK, Eisenberg AL, et al. Increases in human papillomavirus vaccination among adolescent and young adult males in the United States, 2011-2016. J Infect Dis. 2018;218(1):109-113.

4. Dilley S, Scarinci I, Kimberlin D, Straughn JM. Preventing human papillomavirus-related cancers: we are all in this together. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(6):576.e1-576.e5.

5. Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29(32):4294-4301.

6. Chandrani P, Kulkarni V, Iyer P, et al. NGS-based approach to determine the presence of HPV and their sites of integration in human cancer genome. Br J Cancer. 2015;112 (12):1958-1965.

7. Herrero R, Castellsague X, Pawlita M, et al; IARC Multicenter Oral Cancer Study Group. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(23):1772-1783.

8. Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(9):709-720.

9. Golusin´ski W, Leemans CR, Dietz D, eds. HPV Infection in Head and Neck Cancer. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

10. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Increase the vaccination coverage level of 3 doses of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for females by age 13 to 15 years. www.healthypeople.gov/node/4657/data_details. Accessed August 8, 2018.

11. National Cancer Institute; National Institutes of Health. President’s cancer panel annual report 2012–2013. Accelerating HPV vaccine uptake: urgency for action to prevent cancer. https://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/HPV/index.htm. Accessed August 8, 2018.

12. Halpern-Felsher BL, Cornell JL, Kropp RY, Tschann JM. Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):845-851.

13. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Call to action: HPV vaccination as a public health priority. www.nfid.org/publications/cta/hpv-call-to-action.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2018.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7-30.

2. CDC. Human papillomavirus (HPV). www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/whatishpv.html. Accessed August 8, 2018.

3. Patel EU, Grabowski MK, Eisenberg AL, et al. Increases in human papillomavirus vaccination among adolescent and young adult males in the United States, 2011-2016. J Infect Dis. 2018;218(1):109-113.

4. Dilley S, Scarinci I, Kimberlin D, Straughn JM. Preventing human papillomavirus-related cancers: we are all in this together. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(6):576.e1-576.e5.

5. Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29(32):4294-4301.

6. Chandrani P, Kulkarni V, Iyer P, et al. NGS-based approach to determine the presence of HPV and their sites of integration in human cancer genome. Br J Cancer. 2015;112 (12):1958-1965.

7. Herrero R, Castellsague X, Pawlita M, et al; IARC Multicenter Oral Cancer Study Group. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(23):1772-1783.

8. Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(9):709-720.

9. Golusin´ski W, Leemans CR, Dietz D, eds. HPV Infection in Head and Neck Cancer. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

10. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Increase the vaccination coverage level of 3 doses of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for females by age 13 to 15 years. www.healthypeople.gov/node/4657/data_details. Accessed August 8, 2018.

11. National Cancer Institute; National Institutes of Health. President’s cancer panel annual report 2012–2013. Accelerating HPV vaccine uptake: urgency for action to prevent cancer. https://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/HPV/index.htm. Accessed August 8, 2018.

12. Halpern-Felsher BL, Cornell JL, Kropp RY, Tschann JM. Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):845-851.

13. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Call to action: HPV vaccination as a public health priority. www.nfid.org/publications/cta/hpv-call-to-action.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2018.

Brand Who? Brand You!

During the early days of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (incorporated in 1985), I spotted a full-page ad by the Campaign Consultants of America addressed to professional fundraisers. What caught my eye was a photograph of a mother with the tagline, “There’s only one person who understands you better than we do, and she still doesn’t understand what you do for a living.” I pulled the page from the magazine and made a note to consider using it to promote the NP profession. What we needed at the time, despite being an established profession, was to public

Historically, branding has been a task undertaken by a company’s marketing department or an advertising agency to identify elements that differentiate their product from the competition’s. Designing a logo, creating a jingle (Oscar-Mayer, anyone?), or recording a sound bite are the means to emphasize the difference. It paints the mental picture people have of a company, a product, or a provider. These cues remind the consumer about the product. So, how does this apply to the NP (and PA) profession?

The importance of establishing a “brand”—of distinguishing ourselves as competent clinicians with a specific skillset to offer the primary care community—cannot be overstated. Personal branding is a key component of fostering patient loyalty, building your reputation, and increasing referrals to your practice. Understanding the needs and desires of patients, their families, and the community is crucial. Our personal brand emphasizes our assets and expertise. While it can be difficult to look at yourself objectively (especially your assets), it is necessary in today’s competitive world of health care.

NPs constitute the fastest-growing segment of the primary care workforce in the US. More than 50 years of transforming health care as we know it has made us indispensable as health care providers. The literature has long supported the position that NPs provide care that is effective, patient-centered, and evidenced-based. Who we are, what we do, and how well we do it has been documented in myriad reports, surveys, and publications. Yet in many ways, we continue to struggle with an in-between identity. Despite our increasing responsibility in the clinical realm, some are still confused as to who we are.

We are known as nurses first, yet much of the health care we now provide was traditionally in the “physician-only” domain. And because of that history, our ability to function to the fullest extent of our education has been hobbled. These practice restrictions are counterproductive at a time when our nation is facing serious public health challenges.

Over the years, barriers to practice have slowly been whittled away, but full appreciation and recognition of our professional excellence and our contribution to improve the nation’s health is lacking. The fact that much of the research on health status and health ranking fails to include NPs and PAs is testimony that we remain somewhat invisible. And that, my friends, is exactly why it is time to revisit that aforementioned advertisement—not because our mothers don’t know what we do, but because, to some degree, we have eased off the belief that there are still obstacles to full access to NPs as primary care providers. And that is the origin of the need to establish your own brand.

Creating and maintaining your personal brand necessitates that you be multi-functional. You must be a role model, a mentor, and a voice that is respected and reliable. Your brand should advertise what you are known for and what motivates people to seek you, specifically, for their health care needs. Be relentlessly focused on what you do that adds value. As NPs, we have a unique blend of nursing and medicine that allows us to provide the patient-centered care that is central to meeting the existing and future primary care needs of our nation. From our roots in nursing, we offer patients high-quality care and a provider to partner with them in developing their plan of care.

Continue to: A foundational component of building your brand is...

A foundational component of building your brand is positioning yourself as a credible expert and leader. We each have a unique collection of experiences in preventive and primary care. Share that experience by getting involved in your community: participate in health fairs, interact with local news media, or volunteer to serve on your local health board. Emphasize the quality, flexibility, and continuity of care that you can provide. Share any survey findings that demonstrate your ability to anticipate, meet, and even exceed patients’ needs. Demonstrate your ability to deliver quality, accessible health care in a diverse society with increasingly complex medical needs.

As the nation continues to face a shortage of primary care providers and services—a gap that NPs and PAs are equipped to fill—it’s time for us to promote ourselves and advertise all that we can do. This isn’t just for our own sakes, but for our patients’ as well. Give some serious thought (and even more serious effort) to imagining and developing yourself as a brand. Define your brand’s attributes and the qualities or characteristics that make you distinctive from your competitors (or even your colleagues). You are the CEO of brand YOU!

If you have examples of how you promote your personal brand, please share them with me at NPeditor@mdedge.com.

During the early days of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (incorporated in 1985), I spotted a full-page ad by the Campaign Consultants of America addressed to professional fundraisers. What caught my eye was a photograph of a mother with the tagline, “There’s only one person who understands you better than we do, and she still doesn’t understand what you do for a living.” I pulled the page from the magazine and made a note to consider using it to promote the NP profession. What we needed at the time, despite being an established profession, was to public

Historically, branding has been a task undertaken by a company’s marketing department or an advertising agency to identify elements that differentiate their product from the competition’s. Designing a logo, creating a jingle (Oscar-Mayer, anyone?), or recording a sound bite are the means to emphasize the difference. It paints the mental picture people have of a company, a product, or a provider. These cues remind the consumer about the product. So, how does this apply to the NP (and PA) profession?

The importance of establishing a “brand”—of distinguishing ourselves as competent clinicians with a specific skillset to offer the primary care community—cannot be overstated. Personal branding is a key component of fostering patient loyalty, building your reputation, and increasing referrals to your practice. Understanding the needs and desires of patients, their families, and the community is crucial. Our personal brand emphasizes our assets and expertise. While it can be difficult to look at yourself objectively (especially your assets), it is necessary in today’s competitive world of health care.

NPs constitute the fastest-growing segment of the primary care workforce in the US. More than 50 years of transforming health care as we know it has made us indispensable as health care providers. The literature has long supported the position that NPs provide care that is effective, patient-centered, and evidenced-based. Who we are, what we do, and how well we do it has been documented in myriad reports, surveys, and publications. Yet in many ways, we continue to struggle with an in-between identity. Despite our increasing responsibility in the clinical realm, some are still confused as to who we are.

We are known as nurses first, yet much of the health care we now provide was traditionally in the “physician-only” domain. And because of that history, our ability to function to the fullest extent of our education has been hobbled. These practice restrictions are counterproductive at a time when our nation is facing serious public health challenges.

Over the years, barriers to practice have slowly been whittled away, but full appreciation and recognition of our professional excellence and our contribution to improve the nation’s health is lacking. The fact that much of the research on health status and health ranking fails to include NPs and PAs is testimony that we remain somewhat invisible. And that, my friends, is exactly why it is time to revisit that aforementioned advertisement—not because our mothers don’t know what we do, but because, to some degree, we have eased off the belief that there are still obstacles to full access to NPs as primary care providers. And that is the origin of the need to establish your own brand.

Creating and maintaining your personal brand necessitates that you be multi-functional. You must be a role model, a mentor, and a voice that is respected and reliable. Your brand should advertise what you are known for and what motivates people to seek you, specifically, for their health care needs. Be relentlessly focused on what you do that adds value. As NPs, we have a unique blend of nursing and medicine that allows us to provide the patient-centered care that is central to meeting the existing and future primary care needs of our nation. From our roots in nursing, we offer patients high-quality care and a provider to partner with them in developing their plan of care.

Continue to: A foundational component of building your brand is...

A foundational component of building your brand is positioning yourself as a credible expert and leader. We each have a unique collection of experiences in preventive and primary care. Share that experience by getting involved in your community: participate in health fairs, interact with local news media, or volunteer to serve on your local health board. Emphasize the quality, flexibility, and continuity of care that you can provide. Share any survey findings that demonstrate your ability to anticipate, meet, and even exceed patients’ needs. Demonstrate your ability to deliver quality, accessible health care in a diverse society with increasingly complex medical needs.

As the nation continues to face a shortage of primary care providers and services—a gap that NPs and PAs are equipped to fill—it’s time for us to promote ourselves and advertise all that we can do. This isn’t just for our own sakes, but for our patients’ as well. Give some serious thought (and even more serious effort) to imagining and developing yourself as a brand. Define your brand’s attributes and the qualities or characteristics that make you distinctive from your competitors (or even your colleagues). You are the CEO of brand YOU!

If you have examples of how you promote your personal brand, please share them with me at NPeditor@mdedge.com.

During the early days of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (incorporated in 1985), I spotted a full-page ad by the Campaign Consultants of America addressed to professional fundraisers. What caught my eye was a photograph of a mother with the tagline, “There’s only one person who understands you better than we do, and she still doesn’t understand what you do for a living.” I pulled the page from the magazine and made a note to consider using it to promote the NP profession. What we needed at the time, despite being an established profession, was to public

Historically, branding has been a task undertaken by a company’s marketing department or an advertising agency to identify elements that differentiate their product from the competition’s. Designing a logo, creating a jingle (Oscar-Mayer, anyone?), or recording a sound bite are the means to emphasize the difference. It paints the mental picture people have of a company, a product, or a provider. These cues remind the consumer about the product. So, how does this apply to the NP (and PA) profession?

The importance of establishing a “brand”—of distinguishing ourselves as competent clinicians with a specific skillset to offer the primary care community—cannot be overstated. Personal branding is a key component of fostering patient loyalty, building your reputation, and increasing referrals to your practice. Understanding the needs and desires of patients, their families, and the community is crucial. Our personal brand emphasizes our assets and expertise. While it can be difficult to look at yourself objectively (especially your assets), it is necessary in today’s competitive world of health care.

NPs constitute the fastest-growing segment of the primary care workforce in the US. More than 50 years of transforming health care as we know it has made us indispensable as health care providers. The literature has long supported the position that NPs provide care that is effective, patient-centered, and evidenced-based. Who we are, what we do, and how well we do it has been documented in myriad reports, surveys, and publications. Yet in many ways, we continue to struggle with an in-between identity. Despite our increasing responsibility in the clinical realm, some are still confused as to who we are.

We are known as nurses first, yet much of the health care we now provide was traditionally in the “physician-only” domain. And because of that history, our ability to function to the fullest extent of our education has been hobbled. These practice restrictions are counterproductive at a time when our nation is facing serious public health challenges.

Over the years, barriers to practice have slowly been whittled away, but full appreciation and recognition of our professional excellence and our contribution to improve the nation’s health is lacking. The fact that much of the research on health status and health ranking fails to include NPs and PAs is testimony that we remain somewhat invisible. And that, my friends, is exactly why it is time to revisit that aforementioned advertisement—not because our mothers don’t know what we do, but because, to some degree, we have eased off the belief that there are still obstacles to full access to NPs as primary care providers. And that is the origin of the need to establish your own brand.

Creating and maintaining your personal brand necessitates that you be multi-functional. You must be a role model, a mentor, and a voice that is respected and reliable. Your brand should advertise what you are known for and what motivates people to seek you, specifically, for their health care needs. Be relentlessly focused on what you do that adds value. As NPs, we have a unique blend of nursing and medicine that allows us to provide the patient-centered care that is central to meeting the existing and future primary care needs of our nation. From our roots in nursing, we offer patients high-quality care and a provider to partner with them in developing their plan of care.

Continue to: A foundational component of building your brand is...

A foundational component of building your brand is positioning yourself as a credible expert and leader. We each have a unique collection of experiences in preventive and primary care. Share that experience by getting involved in your community: participate in health fairs, interact with local news media, or volunteer to serve on your local health board. Emphasize the quality, flexibility, and continuity of care that you can provide. Share any survey findings that demonstrate your ability to anticipate, meet, and even exceed patients’ needs. Demonstrate your ability to deliver quality, accessible health care in a diverse society with increasingly complex medical needs.

As the nation continues to face a shortage of primary care providers and services—a gap that NPs and PAs are equipped to fill—it’s time for us to promote ourselves and advertise all that we can do. This isn’t just for our own sakes, but for our patients’ as well. Give some serious thought (and even more serious effort) to imagining and developing yourself as a brand. Define your brand’s attributes and the qualities or characteristics that make you distinctive from your competitors (or even your colleagues). You are the CEO of brand YOU!

If you have examples of how you promote your personal brand, please share them with me at NPeditor@mdedge.com.

Up in Arms About Gun Violence

Gun violence in America is a cancer—a metastasis that must be eradicated. As a nation, we continually mourn an ever-rising toll of victims and question why this senseless, tragic loss of life is repeated year after year. What is the reason for the increasing frequency of mass shootings? How is it that we are unable to stem the spread of this plague of gun-related deaths? When will we put an end to the massacres?

All good questions. And they have once again become the hue and cry of many people in the wake of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. This particular tragedy marked the 30th mass shooting in 2018—in other words, the latest in a line of tragedies that “should have” been preventable.1

Whatever your political stance on the issue of guns, surely we can all agree that it is a problem that more than 549,000 acts of gun violence occur each year.2 In 2015 (the most recent year for which a National Vital Statistics Report is available), there were 36,252 firearm-related deaths in the US—a rate of 11.1 deaths per 100,000 population. From 2012 to 2014, nearly 1,300 children died each year from a firearm-related injury.3 These statistics support the need to change our thinking about guns and gun violence.

Thus far, the discussion about gun control has tended to focus on passing and enforcing laws. We know that the US, compared to other countries, has fairly lenient restrictions for who can buy a gun and what kinds of guns can be purchased.4 In fact, many Americans can buy a gun in less than an hour, while in some countries, the process takes months.4 Furthermore, across the nation, there is no systematic fashion of gun regulation or ownership.

The challenge of how to balance gun safety and gun rights is an ongoing, yet one-focus, approach. The debate needs to be broadened; it’s time we stop talking about just the gun. We need to address the problem of firearm injuries in the context of a public health issue.5

A common assumption is that mental illness or high stress levels trigger gun violence. According to data from the Sandy Hook Promise organization, most criminal gun violence is committed by individuals who lack mental wellness (ie, coping skills, anger management, and other social/emotional skills).6 But other statistics contradict that notion. For example, a 2011 report in The Atlantic did not support mental illness as a causative factor in gun violence.7 And evidence presented by the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy indicates that the majority of people with mental illness do not engage in violence against others.8 The Consortium noted, however, that a small group of individuals with serious mental illness does have a propensity toward violence. It is this—the risk for dangerous behavior, rather than mental illness alone—that must be the focus for preventing gun violence.

Dangerous behaviors are those that carry a high risk for harm or injury to oneself or others.9 Emotional problems, social conflicts, access to weapons, and altered states of mind (via alcohol and drugs) all contribute to violent and homicidal behavior in adolescents.10 A worrisome fact: A nationwide study of mass shootings from 2009 to 2016 revealed that in at least 42% of these incidents there was documentation that the attacker exhibited dangerous warning signs before the shooting.11 So, in many cases of violent behavior, the perpetrator threatens others or his own life before actually carrying out his plan.12 But surely we must be able to do more than sit and watch for warning signs.

Continue to: Might tighter gun control laws...

Might tighter gun control laws help to mitigate this crisis? Perhaps; but we must also consider the importance of mental health care reform. In order to prevent gun violence, we need to understand (and address) the cause. We therefore need funding for mental health services to assist those who are at risk for harming themselves and others.

Instead of solely viewing gun control as a yes-or-no issue, we need to examine the intersection between mental health and violence. While our mental health care system is not equipped to help everyone, we need to acknowledge that gun-related deaths are preventable—and we need to make the choice to invest in that prevention.

Thus far, the ongoing debate about gun safety has largely centered around the Second Amendment, which has a two-fold obligation: the right of US citizens to be protected from violence and the right of the people to bear arms. Proponents on both sides of this polarizing issue have rallied to support their position; this often takes the form of shouting and counter-shouting (and sometimes threats)—and we make no progress on the core issue, which is that too many people in this country die because of gun violence.

We stand at the crossroads of realizing that something must be done. Share your reasoned suggestions (no rants, please!) for how we, as a nation, can combat gun violence and gun-related deaths with me at NPeditor@mdedge.com.

1. Robinson M, Gould S. There have been 30 mass shootings in the US so far in 2018 – here’s the full list. February 15, 2018. www.businessinsider.com/how-many-mass-shootings-in-america-this-year-2018-2. Accessed April 13, 2018.

2. CDC; Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek K, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports. Deaths: final data for 2015. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr66/nvsr66_06.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2018.

3. Fowler KA, Dahlberg LL, Haileyesus T, et al. Childhood firearm injuries in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1): e20163486.

4. Carlsen A, Chinoy S. How to buy a gun in 15 countries. The New York Times. March 2, 2018.

5. Grinshteyn E, Hemenway D. Violent death rates: the US compared with other high-income OECD countries, 2010. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):266-273.

6. Gun violence in America fact sheet: average 2003-2013. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/promise/pages/17/attachments/original/1445441287/Gun_Facts.pdf?1445441287. Accessed April 13, 2018.

7. Florida R. The geography of gun deaths. January 13, 2011. The Atlantic. Accessed April 13, 2018.

8. Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy. Guns, public health, and mental illness: an evidence-based approach for state policy. December 2, 2013. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-policy-and-research/publications/GPHMI-State.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2018.

9. Conner MG. The risk of violent and homicidal behavior in children. May 21, 2014. http://oregoncounseling.org/ArticlesPapers/Documents/childviolence.htm. Accessed April 13, 2018.

10. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Dangerous behavior. www.definitions.net/definition/dangerous behavior.11. Everytown for Gun Safety. Mass shootings in the United States: 2009-2016. March 2017. https://everytownresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Analysis_of_Mass_Shooting_062117.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2018.

12. Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights. Assessing lethal and extremely dangerous behavior. www.hotpeachpages.net/lang/EnglishTraining/LethalityModule_2.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2018.

Gun violence in America is a cancer—a metastasis that must be eradicated. As a nation, we continually mourn an ever-rising toll of victims and question why this senseless, tragic loss of life is repeated year after year. What is the reason for the increasing frequency of mass shootings? How is it that we are unable to stem the spread of this plague of gun-related deaths? When will we put an end to the massacres?

All good questions. And they have once again become the hue and cry of many people in the wake of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. This particular tragedy marked the 30th mass shooting in 2018—in other words, the latest in a line of tragedies that “should have” been preventable.1

Whatever your political stance on the issue of guns, surely we can all agree that it is a problem that more than 549,000 acts of gun violence occur each year.2 In 2015 (the most recent year for which a National Vital Statistics Report is available), there were 36,252 firearm-related deaths in the US—a rate of 11.1 deaths per 100,000 population. From 2012 to 2014, nearly 1,300 children died each year from a firearm-related injury.3 These statistics support the need to change our thinking about guns and gun violence.

Thus far, the discussion about gun control has tended to focus on passing and enforcing laws. We know that the US, compared to other countries, has fairly lenient restrictions for who can buy a gun and what kinds of guns can be purchased.4 In fact, many Americans can buy a gun in less than an hour, while in some countries, the process takes months.4 Furthermore, across the nation, there is no systematic fashion of gun regulation or ownership.

The challenge of how to balance gun safety and gun rights is an ongoing, yet one-focus, approach. The debate needs to be broadened; it’s time we stop talking about just the gun. We need to address the problem of firearm injuries in the context of a public health issue.5

A common assumption is that mental illness or high stress levels trigger gun violence. According to data from the Sandy Hook Promise organization, most criminal gun violence is committed by individuals who lack mental wellness (ie, coping skills, anger management, and other social/emotional skills).6 But other statistics contradict that notion. For example, a 2011 report in The Atlantic did not support mental illness as a causative factor in gun violence.7 And evidence presented by the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy indicates that the majority of people with mental illness do not engage in violence against others.8 The Consortium noted, however, that a small group of individuals with serious mental illness does have a propensity toward violence. It is this—the risk for dangerous behavior, rather than mental illness alone—that must be the focus for preventing gun violence.

Dangerous behaviors are those that carry a high risk for harm or injury to oneself or others.9 Emotional problems, social conflicts, access to weapons, and altered states of mind (via alcohol and drugs) all contribute to violent and homicidal behavior in adolescents.10 A worrisome fact: A nationwide study of mass shootings from 2009 to 2016 revealed that in at least 42% of these incidents there was documentation that the attacker exhibited dangerous warning signs before the shooting.11 So, in many cases of violent behavior, the perpetrator threatens others or his own life before actually carrying out his plan.12 But surely we must be able to do more than sit and watch for warning signs.

Continue to: Might tighter gun control laws...

Might tighter gun control laws help to mitigate this crisis? Perhaps; but we must also consider the importance of mental health care reform. In order to prevent gun violence, we need to understand (and address) the cause. We therefore need funding for mental health services to assist those who are at risk for harming themselves and others.

Instead of solely viewing gun control as a yes-or-no issue, we need to examine the intersection between mental health and violence. While our mental health care system is not equipped to help everyone, we need to acknowledge that gun-related deaths are preventable—and we need to make the choice to invest in that prevention.

Thus far, the ongoing debate about gun safety has largely centered around the Second Amendment, which has a two-fold obligation: the right of US citizens to be protected from violence and the right of the people to bear arms. Proponents on both sides of this polarizing issue have rallied to support their position; this often takes the form of shouting and counter-shouting (and sometimes threats)—and we make no progress on the core issue, which is that too many people in this country die because of gun violence.

We stand at the crossroads of realizing that something must be done. Share your reasoned suggestions (no rants, please!) for how we, as a nation, can combat gun violence and gun-related deaths with me at NPeditor@mdedge.com.

Gun violence in America is a cancer—a metastasis that must be eradicated. As a nation, we continually mourn an ever-rising toll of victims and question why this senseless, tragic loss of life is repeated year after year. What is the reason for the increasing frequency of mass shootings? How is it that we are unable to stem the spread of this plague of gun-related deaths? When will we put an end to the massacres?

All good questions. And they have once again become the hue and cry of many people in the wake of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. This particular tragedy marked the 30th mass shooting in 2018—in other words, the latest in a line of tragedies that “should have” been preventable.1

Whatever your political stance on the issue of guns, surely we can all agree that it is a problem that more than 549,000 acts of gun violence occur each year.2 In 2015 (the most recent year for which a National Vital Statistics Report is available), there were 36,252 firearm-related deaths in the US—a rate of 11.1 deaths per 100,000 population. From 2012 to 2014, nearly 1,300 children died each year from a firearm-related injury.3 These statistics support the need to change our thinking about guns and gun violence.

Thus far, the discussion about gun control has tended to focus on passing and enforcing laws. We know that the US, compared to other countries, has fairly lenient restrictions for who can buy a gun and what kinds of guns can be purchased.4 In fact, many Americans can buy a gun in less than an hour, while in some countries, the process takes months.4 Furthermore, across the nation, there is no systematic fashion of gun regulation or ownership.

The challenge of how to balance gun safety and gun rights is an ongoing, yet one-focus, approach. The debate needs to be broadened; it’s time we stop talking about just the gun. We need to address the problem of firearm injuries in the context of a public health issue.5

A common assumption is that mental illness or high stress levels trigger gun violence. According to data from the Sandy Hook Promise organization, most criminal gun violence is committed by individuals who lack mental wellness (ie, coping skills, anger management, and other social/emotional skills).6 But other statistics contradict that notion. For example, a 2011 report in The Atlantic did not support mental illness as a causative factor in gun violence.7 And evidence presented by the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy indicates that the majority of people with mental illness do not engage in violence against others.8 The Consortium noted, however, that a small group of individuals with serious mental illness does have a propensity toward violence. It is this—the risk for dangerous behavior, rather than mental illness alone—that must be the focus for preventing gun violence.

Dangerous behaviors are those that carry a high risk for harm or injury to oneself or others.9 Emotional problems, social conflicts, access to weapons, and altered states of mind (via alcohol and drugs) all contribute to violent and homicidal behavior in adolescents.10 A worrisome fact: A nationwide study of mass shootings from 2009 to 2016 revealed that in at least 42% of these incidents there was documentation that the attacker exhibited dangerous warning signs before the shooting.11 So, in many cases of violent behavior, the perpetrator threatens others or his own life before actually carrying out his plan.12 But surely we must be able to do more than sit and watch for warning signs.

Continue to: Might tighter gun control laws...

Might tighter gun control laws help to mitigate this crisis? Perhaps; but we must also consider the importance of mental health care reform. In order to prevent gun violence, we need to understand (and address) the cause. We therefore need funding for mental health services to assist those who are at risk for harming themselves and others.

Instead of solely viewing gun control as a yes-or-no issue, we need to examine the intersection between mental health and violence. While our mental health care system is not equipped to help everyone, we need to acknowledge that gun-related deaths are preventable—and we need to make the choice to invest in that prevention.

Thus far, the ongoing debate about gun safety has largely centered around the Second Amendment, which has a two-fold obligation: the right of US citizens to be protected from violence and the right of the people to bear arms. Proponents on both sides of this polarizing issue have rallied to support their position; this often takes the form of shouting and counter-shouting (and sometimes threats)—and we make no progress on the core issue, which is that too many people in this country die because of gun violence.

We stand at the crossroads of realizing that something must be done. Share your reasoned suggestions (no rants, please!) for how we, as a nation, can combat gun violence and gun-related deaths with me at NPeditor@mdedge.com.

1. Robinson M, Gould S. There have been 30 mass shootings in the US so far in 2018 – here’s the full list. February 15, 2018. www.businessinsider.com/how-many-mass-shootings-in-america-this-year-2018-2. Accessed April 13, 2018.

2. CDC; Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek K, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports. Deaths: final data for 2015. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr66/nvsr66_06.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2018.

3. Fowler KA, Dahlberg LL, Haileyesus T, et al. Childhood firearm injuries in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1): e20163486.

4. Carlsen A, Chinoy S. How to buy a gun in 15 countries. The New York Times. March 2, 2018.

5. Grinshteyn E, Hemenway D. Violent death rates: the US compared with other high-income OECD countries, 2010. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):266-273.

6. Gun violence in America fact sheet: average 2003-2013. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/promise/pages/17/attachments/original/1445441287/Gun_Facts.pdf?1445441287. Accessed April 13, 2018.

7. Florida R. The geography of gun deaths. January 13, 2011. The Atlantic. Accessed April 13, 2018.

8. Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy. Guns, public health, and mental illness: an evidence-based approach for state policy. December 2, 2013. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-policy-and-research/publications/GPHMI-State.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2018.

9. Conner MG. The risk of violent and homicidal behavior in children. May 21, 2014. http://oregoncounseling.org/ArticlesPapers/Documents/childviolence.htm. Accessed April 13, 2018.

10. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Dangerous behavior. www.definitions.net/definition/dangerous behavior.11. Everytown for Gun Safety. Mass shootings in the United States: 2009-2016. March 2017. https://everytownresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Analysis_of_Mass_Shooting_062117.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2018.

12. Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights. Assessing lethal and extremely dangerous behavior. www.hotpeachpages.net/lang/EnglishTraining/LethalityModule_2.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2018.

1. Robinson M, Gould S. There have been 30 mass shootings in the US so far in 2018 – here’s the full list. February 15, 2018. www.businessinsider.com/how-many-mass-shootings-in-america-this-year-2018-2. Accessed April 13, 2018.

2. CDC; Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek K, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports. Deaths: final data for 2015. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr66/nvsr66_06.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2018.

3. Fowler KA, Dahlberg LL, Haileyesus T, et al. Childhood firearm injuries in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1): e20163486.

4. Carlsen A, Chinoy S. How to buy a gun in 15 countries. The New York Times. March 2, 2018.

5. Grinshteyn E, Hemenway D. Violent death rates: the US compared with other high-income OECD countries, 2010. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):266-273.

6. Gun violence in America fact sheet: average 2003-2013. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/promise/pages/17/attachments/original/1445441287/Gun_Facts.pdf?1445441287. Accessed April 13, 2018.

7. Florida R. The geography of gun deaths. January 13, 2011. The Atlantic. Accessed April 13, 2018.

8. Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy. Guns, public health, and mental illness: an evidence-based approach for state policy. December 2, 2013. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-policy-and-research/publications/GPHMI-State.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2018.

9. Conner MG. The risk of violent and homicidal behavior in children. May 21, 2014. http://oregoncounseling.org/ArticlesPapers/Documents/childviolence.htm. Accessed April 13, 2018.

10. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Dangerous behavior. www.definitions.net/definition/dangerous behavior.11. Everytown for Gun Safety. Mass shootings in the United States: 2009-2016. March 2017. https://everytownresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Analysis_of_Mass_Shooting_062117.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2018.

12. Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights. Assessing lethal and extremely dangerous behavior. www.hotpeachpages.net/lang/EnglishTraining/LethalityModule_2.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2018.

Taking the Bite Out of Nutrition

As March arrives, we rejoice in the promise of spring sunlight and start planning ahead for summer and its associated clothing, which tends to be a bit more … revealing, shall we say. If we’re really motivated, we might dust off our (quickly forgotten) New Year’s weight-loss resolutions, adjusting our carb:veggie ratio to get beach-ready. Furthermore, March historically signified the start of farming season—making it a natural fit for National Nutrition Month.

In 1973, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) initiated a week-long campaign to educate the public about hea

This guidance is needed more now than ever before. About 75% of Americans follow a diet that is low in fruits, vegetables, dairy, and oils (compared to the recommended values)—and most exceed the recommended allotment for added sugars, sodium, and saturated fats.2 It’s no surprise, then, that two-thirds of US adults are either overweight or obese.2

It is imperative that we, as health care providers, provide our patients and their families with practical, evidence-based information about healthy food choices. But are we sufficiently educated to provide that guidance?

I admit, my confidence in my nutritional knowledge falls short of the mark. I vaguely recall nutrition being discussed in one of my basic nursing courses; diets designed for specific disease entities were introduced as I progressed in my education. But a specific nutrition course is not a requirement in the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education’s Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice—even though nutrition is directly linked to wellness and health promotion is an essential component of nursing practice.3 (This inconsistency in nutrition education holds true for our PA colleagues, as well.)

How, then, do we educate ourselves so that we can impart the necessary guidance to our patients? The plethora of articles—some more scholarly than others—on what we should and should not eat can be very confusing.

Generally, though, the soundest advice encourages a healthy lifestyle, with emphasis on consistent, enjoyable eating practices and regular physical activity. Of particular note: The word “diet” is not included in most guides. Rather, we are advised to make small changes to the way we think about eating.

Substituting fruit for added sugar, whole grains for refined grains, and oils for solid fats are just a few simple ways to transition to a healthier eating regimen.2 Another adaptation is to plan out meals and snacks prior to food shopping; this not only prevents us from making poor choices and purchasing items based on impulse or hunger, but also decreases food waste. These comparatively small adjustments can make a real difference over time.

To help achieve the goal of a healthy lifestyle, AND offers the following suggestions:

- Include a variety of healthful foods from all food groups on a regular basis.

- Consider which food items you have on hand before buying more at the store.

- Buy only an amount that can be eaten within a few days (or stored in the freezer) and plan ways to use leftovers later in the week.

- Be mindful of portion sizes.

- Find activities you enjoy to keep you physically active throughout the week.4

We also have a resource at our fingertips that we often overlook: registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs). These professionals are educated specifically to provide counseling on food choices and can help clear the murky waters surrounding nutrition. An RDN can partner with a consumer to develop a safe, effective, sustainable eating plan that takes into consideration health status, lifestyle, and personal taste preferences.

In addition to RDN colleagues, there are trustworthy, easy-to-navigate websites that provide resources on nutrition and healthy eating. They also have tools we can provide to our patients and their families (see box). For example, ChooseMyPlate (www.choosemyplate.gov) is an interactive site based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans that provides information on how much of each food group should be eaten each day. It also includes resources for planning well-balanced, healthy meals and a series of fact sheets with tips that can be useful for patients. The National Institutes of Health also offers practical guidance on differentiating a portion from a serving, controlling portion size (both at home and when eating out), and finding alternatives to salt when you want or need to season food.

Reviewing even just one or two of these resources can improve your knowledge about healthy eating habits. Since a balanced and tasty meal plan is a recipe for success, let’s make better nutrition our mantra. We can help our patients, and perhaps learn something ourselves!

1. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month®. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/national-nutrition-month. Accessed February 13, 2018.

2. US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th ed. 2015. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines. Accessed February 13, 2018.

3. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice. 2008. www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Publications/BaccEssentials08.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2018.

4. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month® celebration toolkit. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/toolkit. Accessed February 13, 2018.

As March arrives, we rejoice in the promise of spring sunlight and start planning ahead for summer and its associated clothing, which tends to be a bit more … revealing, shall we say. If we’re really motivated, we might dust off our (quickly forgotten) New Year’s weight-loss resolutions, adjusting our carb:veggie ratio to get beach-ready. Furthermore, March historically signified the start of farming season—making it a natural fit for National Nutrition Month.

In 1973, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) initiated a week-long campaign to educate the public about hea

This guidance is needed more now than ever before. About 75% of Americans follow a diet that is low in fruits, vegetables, dairy, and oils (compared to the recommended values)—and most exceed the recommended allotment for added sugars, sodium, and saturated fats.2 It’s no surprise, then, that two-thirds of US adults are either overweight or obese.2

It is imperative that we, as health care providers, provide our patients and their families with practical, evidence-based information about healthy food choices. But are we sufficiently educated to provide that guidance?

I admit, my confidence in my nutritional knowledge falls short of the mark. I vaguely recall nutrition being discussed in one of my basic nursing courses; diets designed for specific disease entities were introduced as I progressed in my education. But a specific nutrition course is not a requirement in the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education’s Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice—even though nutrition is directly linked to wellness and health promotion is an essential component of nursing practice.3 (This inconsistency in nutrition education holds true for our PA colleagues, as well.)

How, then, do we educate ourselves so that we can impart the necessary guidance to our patients? The plethora of articles—some more scholarly than others—on what we should and should not eat can be very confusing.

Generally, though, the soundest advice encourages a healthy lifestyle, with emphasis on consistent, enjoyable eating practices and regular physical activity. Of particular note: The word “diet” is not included in most guides. Rather, we are advised to make small changes to the way we think about eating.

Substituting fruit for added sugar, whole grains for refined grains, and oils for solid fats are just a few simple ways to transition to a healthier eating regimen.2 Another adaptation is to plan out meals and snacks prior to food shopping; this not only prevents us from making poor choices and purchasing items based on impulse or hunger, but also decreases food waste. These comparatively small adjustments can make a real difference over time.

To help achieve the goal of a healthy lifestyle, AND offers the following suggestions:

- Include a variety of healthful foods from all food groups on a regular basis.

- Consider which food items you have on hand before buying more at the store.

- Buy only an amount that can be eaten within a few days (or stored in the freezer) and plan ways to use leftovers later in the week.

- Be mindful of portion sizes.

- Find activities you enjoy to keep you physically active throughout the week.4

We also have a resource at our fingertips that we often overlook: registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs). These professionals are educated specifically to provide counseling on food choices and can help clear the murky waters surrounding nutrition. An RDN can partner with a consumer to develop a safe, effective, sustainable eating plan that takes into consideration health status, lifestyle, and personal taste preferences.

In addition to RDN colleagues, there are trustworthy, easy-to-navigate websites that provide resources on nutrition and healthy eating. They also have tools we can provide to our patients and their families (see box). For example, ChooseMyPlate (www.choosemyplate.gov) is an interactive site based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans that provides information on how much of each food group should be eaten each day. It also includes resources for planning well-balanced, healthy meals and a series of fact sheets with tips that can be useful for patients. The National Institutes of Health also offers practical guidance on differentiating a portion from a serving, controlling portion size (both at home and when eating out), and finding alternatives to salt when you want or need to season food.

Reviewing even just one or two of these resources can improve your knowledge about healthy eating habits. Since a balanced and tasty meal plan is a recipe for success, let’s make better nutrition our mantra. We can help our patients, and perhaps learn something ourselves!

As March arrives, we rejoice in the promise of spring sunlight and start planning ahead for summer and its associated clothing, which tends to be a bit more … revealing, shall we say. If we’re really motivated, we might dust off our (quickly forgotten) New Year’s weight-loss resolutions, adjusting our carb:veggie ratio to get beach-ready. Furthermore, March historically signified the start of farming season—making it a natural fit for National Nutrition Month.

In 1973, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) initiated a week-long campaign to educate the public about hea

This guidance is needed more now than ever before. About 75% of Americans follow a diet that is low in fruits, vegetables, dairy, and oils (compared to the recommended values)—and most exceed the recommended allotment for added sugars, sodium, and saturated fats.2 It’s no surprise, then, that two-thirds of US adults are either overweight or obese.2

It is imperative that we, as health care providers, provide our patients and their families with practical, evidence-based information about healthy food choices. But are we sufficiently educated to provide that guidance?

I admit, my confidence in my nutritional knowledge falls short of the mark. I vaguely recall nutrition being discussed in one of my basic nursing courses; diets designed for specific disease entities were introduced as I progressed in my education. But a specific nutrition course is not a requirement in the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education’s Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice—even though nutrition is directly linked to wellness and health promotion is an essential component of nursing practice.3 (This inconsistency in nutrition education holds true for our PA colleagues, as well.)

How, then, do we educate ourselves so that we can impart the necessary guidance to our patients? The plethora of articles—some more scholarly than others—on what we should and should not eat can be very confusing.

Generally, though, the soundest advice encourages a healthy lifestyle, with emphasis on consistent, enjoyable eating practices and regular physical activity. Of particular note: The word “diet” is not included in most guides. Rather, we are advised to make small changes to the way we think about eating.

Substituting fruit for added sugar, whole grains for refined grains, and oils for solid fats are just a few simple ways to transition to a healthier eating regimen.2 Another adaptation is to plan out meals and snacks prior to food shopping; this not only prevents us from making poor choices and purchasing items based on impulse or hunger, but also decreases food waste. These comparatively small adjustments can make a real difference over time.

To help achieve the goal of a healthy lifestyle, AND offers the following suggestions:

- Include a variety of healthful foods from all food groups on a regular basis.

- Consider which food items you have on hand before buying more at the store.

- Buy only an amount that can be eaten within a few days (or stored in the freezer) and plan ways to use leftovers later in the week.

- Be mindful of portion sizes.

- Find activities you enjoy to keep you physically active throughout the week.4

We also have a resource at our fingertips that we often overlook: registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs). These professionals are educated specifically to provide counseling on food choices and can help clear the murky waters surrounding nutrition. An RDN can partner with a consumer to develop a safe, effective, sustainable eating plan that takes into consideration health status, lifestyle, and personal taste preferences.

In addition to RDN colleagues, there are trustworthy, easy-to-navigate websites that provide resources on nutrition and healthy eating. They also have tools we can provide to our patients and their families (see box). For example, ChooseMyPlate (www.choosemyplate.gov) is an interactive site based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans that provides information on how much of each food group should be eaten each day. It also includes resources for planning well-balanced, healthy meals and a series of fact sheets with tips that can be useful for patients. The National Institutes of Health also offers practical guidance on differentiating a portion from a serving, controlling portion size (both at home and when eating out), and finding alternatives to salt when you want or need to season food.

Reviewing even just one or two of these resources can improve your knowledge about healthy eating habits. Since a balanced and tasty meal plan is a recipe for success, let’s make better nutrition our mantra. We can help our patients, and perhaps learn something ourselves!

1. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month®. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/national-nutrition-month. Accessed February 13, 2018.

2. US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th ed. 2015. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines. Accessed February 13, 2018.

3. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice. 2008. www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Publications/BaccEssentials08.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2018.

4. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month® celebration toolkit. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/toolkit. Accessed February 13, 2018.

1. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month®. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/national-nutrition-month. Accessed February 13, 2018.

2. US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th ed. 2015. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines. Accessed February 13, 2018.

3. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice. 2008. www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Publications/BaccEssentials08.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2018.

4. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month® celebration toolkit. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/toolkit. Accessed February 13, 2018.

Stressed for Success

As I write this column, the holiday season has just begun, and its incumbent demands lie ahead. By the time this article reaches you, we will have outlasted the season and its associated stress. But it’s not just the holiday baking, gift-wrapping, and decorating that overwhelms us—we face enormous professional stress during this time of year, with its emphasis on home, family, good health, and harmony.

Stress is simply a part of human nature. And despite its bad rap, not all stress is problematic; it’s what motivates people to prepare or perform. Routine, “normal” stress that is temporary or short-lived can actually be beneficial. When placed in danger, the body prepares to either face the threat or flee to safety. During these times, your pulse quickens, you breathe faster, your muscles tense, your brain uses more oxygen and increases activity—all functions that aid in survival.1

But not every situation we encounter necessitates an increase in endorphin levels and blood pressure. Tell that to our stress levels, which are often persistently elevated! Chronic stress can cause the self-protective responses your body activates when threatened to suppress immune, digestive, sleep, and reproductive systems, leading them to cease normal functioning over time.1 This “bad” stress—or distress—can contribute to health problems such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes.

Stress can elicit a variety of responses: behavioral, psychologic/emotional, physical, cognitive, and social.2 For many, consumption (of tobacco, alcohol, drugs, sugar, fat, or caffeine) is a coping mechanism. While many people look to food for comfort and stress relief, research suggests it may have undesired effects. Eating a high-fat meal when under stress can slow your metabolism and result in significant weight gain.3 Stress can also influence whether people undereat or overeat and affect neurohormonal activity—which leads to increased production of cortisol, which leads to weight gain (particularly in women).4 Let’s be honest: Gaining weight seldom lowers someone’s stress level.

Everyone has different triggers that cause their stress levels to spike, but the workplace has been found to top the list. Within the “work” category, commonly reported stressors include

- Heavy workload or too much responsibility

- Long hours

- Poor management, unclear expectations, or having no say in decision-making.5

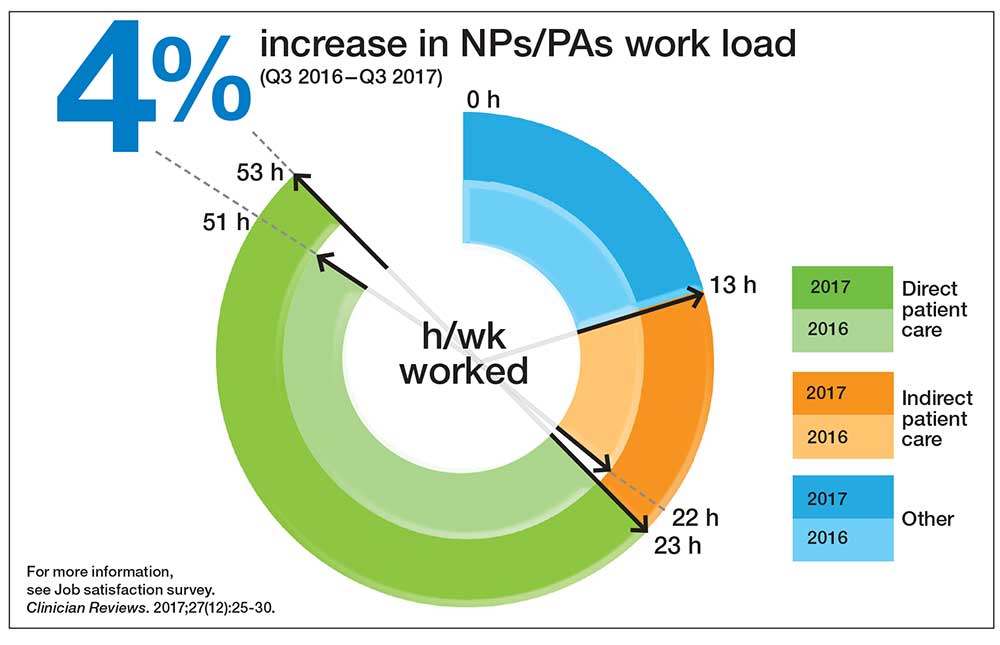

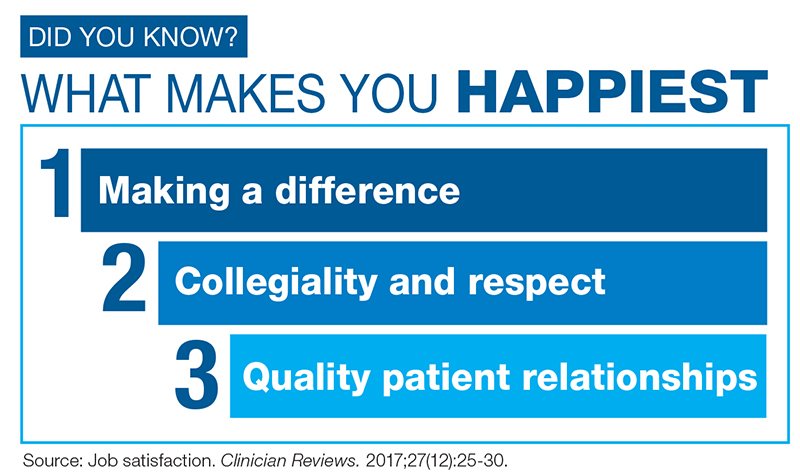

For health care providers, day-to-day stress is a chronic problem; responses to the Clinician Reviews annual job satisfaction survey have demonstrated that.6,7 Many of our readers report ongoing issues related to scheduling, work/life balance, compensation, and working conditions. That tension has a direct negative effect, not only on us, but on our families and our patients as well. A missed soccer game or a holiday on call are obvious stressors—but our inability to help patients achieve optimal health is a source of distress that we may not recognize the ramifications of. How often has a clinician felt caught in what feels like an unattainable quest?

Mitigating this workplace stress is the challenge. Changing jobs is another high-stress event, so up and quitting is probably not the answer. Identifying the problem is the first essential step.

If workload is the issue, focus on setting realistic goals for your day. Goal-setting provides purposeful direction and helps you feel in control. There will undeniably be days in which your plan must be completely abandoned. When this happens, don’t fret—reassess! Decide what must get done and what can wait. If possible, avoid scheduling patient appointments that will put you into overload. Learn to say “no” without feeling as though you are not a team player. And when you feel swamped, put a positive spin on the day by noting what you have accomplished, rather than what you have been unable to achieve.

If you find that your voice is but a whisper in the decision-making process, look for ways to become more involved. How can you provide direction on issues relating to organizational structure and clinical efficiency? Don’t suppress your feelings or concerns about the work environment. Pulling up a chair at the management table is crucial to improving the workplace and reducing stress for everyone (including the management!). Discuss key frustration points. Clear documentation of the issues that impede patient satisfaction (eg, long wait times) will aid in your dialogue.