User login

Precepting: Holding Students and Programs Accountable

Randy Danielsen’s editorial on the topic of precepting (April 2016) elicited a flurry of responses from our NP readers.1 The influx of feedback prompted me as an educator, an NP, and a former preceptor to wonder: Why the paucity of preceptors? Are there too many programs and too many students? And are we dropping the ball when it comes to engendering professional responsibility as a “social contract”?1

Let me start with a query: Are we requiring students to uphold their social contracts? That is, are they engaged in professional networking to enrich their own clinical experiences? Are they responsible for establishing relationships with providers in their communities in preparation for clinical rotations? Aren’t these all components of their social contracts as students?

In my PNP program, we found our own preceptors (there were no clinical coordinators “back in the day”). As a component of that, we often had to educate our preceptors on the role of the NP. Thankfully, the pediatric community was aware of the NP; in the Boston area, at least, many settings already had NPs (and PAs) as providers. Still, when I reflect back, the experience of finding a preceptor augmented my professional education. It also instilled in me responsibility for my own professional development.

When it was my turn, I agreed to precept as my contribution to the profession. However, my first foray into precepting was not a pleasant one. As some of our email authors attested to experiencing, my student was completely unprepared for her clinical rotation. I found myself teaching basic assessment skills (to a student in her final semester!), which takes considerable time in the office setting. Subsequently, I required students to have at least three years of RN experience and demonstrate a full H&P prior to acceptance. This proviso raised some eyebrows among my colleagues, but as I saw it, my role as a preceptor was to help students to improve their skills—not teach them the basics. The result: a happy preceptor and long-standing relationships with the precepted students.

Even so, like many of the clinicians who responded to Dr. Danielsen’s editorial, I must admit I eventually stopped precepting. My decision was based on several factors, but the primary reason was that the students and faculty recruiting me were somewhat cavalier in their responsibility for preparedness to practice.

Among the readers who shared their precepting experiences, many cited inexperience in the RN role as a significant issue, as well as the rapidity with which students progress through their NP programs. Some commented that there is too much material to understand and process and not enough time to master the skills. These observations lead me back to the idea of “too many programs and students.” I know I risk offending my colleagues in academia with that statement. But I also know, from conversations with colleagues and the volume of emails we received on this topic, that many preceptors are frustrated by some students’ lack of responsibility, motivation, and preparation for their clinical rotations.

Some chalk up this shortcoming to being “millennials.” Others suggest that online programs do not hold students accountable for the “real world” demands of the job. On the latter point, I would submit that the “brick and mortar” programs have similar issues with students. And while both of these points have some validity, I think the problem is more complicated.

We face a perfect storm in NP education: The demand for NPs has increased as a result of the implementation of the ACA. In response to this demand, the number of NP programs has grown, and so has the need for NP preceptors. Yet, at this critical time, the number of preceptors is dwindling (in volume, yes, but also in willingness).

To resolve this conundrum, we must take a closer look at ways we can reverse the declining interest in preceptorship. Increasing the number of available preceptors requires overcoming perceived barriers. One of these, as noted by Barker and Pittman, is the detrimental effect precepting has on productivity.2 To illustrate this, they presented findings from a study of community physicians that documented an increase in the time taken to see patients and a decrease in the number of patients seen when the physician was precepting students.3 Additional time and reduced productivity are not tolerated in today’s work environment, and patients, who increasingly see themselves as health care consumers (who can take their “business” elsewhere), don’t appreciate waiting to see their health care provider when they have an appointment.

In their research, Logan, Kovacs, and Barry also found that productivity expectations (or should I say, the expectation of reduced productivity) impeded willingness to precept.4 They identified lack of time in the workday as a major barrier. This point is difficult to counter, I admit. But they also presented two other deterrents that, conversely, I view as potential opportunities for increasing the number of willing preceptors:

Lack of training for preceptors. Preceptors must learn how to fulfill this role on their own, without any training or support. This is a significant problem, not only for nascent preceptors but also for seasoned ones, who often precept students from different programs with a variety of requirements and expectations (and paperwork!). In an editorial, a new preceptor expressed concern about her ability to “get it right” and give her student what was needed to accomplish the goals for the rotation.5 Training and supportive testimonies are essential for successful precepting. A simple approach would be for program faculty to “mentor” new preceptors: Spend time orienting them to the expectations of the program and explaining how to evaluate students. Be proactive—establish weekly conference calls and share both strategies for successful precepting relationships and the “pitfalls to avoid.”

Student preparation. The other problem discussed by Logan, Kovacs, and Barry—and attested to by many of our readers—was the skill level and readiness of students on the first day of their clinical experience. While this responsibility lies with the student (rightfully so), I believe awareness of this problem, and understanding of how it affects practitioners’ willingness to precept, offers an opportunity for our education programs. Students may not know what they don’t know, or some may be too timid to speak up if they feel unprepared to step into a clinical arena (not to confuse that unease with “first-day jitters”). It is incumbent on the program faculty to ensure their students—who are representatives of that program and the faculty—are ready for clinical rotations. What do they need to do? Conduct an assessment of skills and readiness, which would assist all parties—the student, the preceptor, and the faculty—in gauging the progress of skill improvement and student competency and capability as a provider. It is also imperative that any remediation be provided by the program (prior to the student’s entrance into the clinical setting) and not the preceptor.

The bottom line is that precepting is a partnership between the skilled practitioner, the NP faculty, and the focused student.2 The responsibility for a mutually enjoyable and rewarding experience lies with all parties involved. As seasoned NPs, we must be active participants in preparing the next generation of our colleagues. That is our professional responsibility—our fulfillment of the “social contract.” We owe it to them, we owe it to our patients, and we owe it to ourselves—because someday, down the road, these clinicians will be taking care of us!

When a topic merits two editorials, there is clearly much to discuss. What steps do you suggest we undertake to mitigate this conundrum? Share your ideas by writing to me at NPEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Danielsen RD. The death of altruism, or, can I get a preceptor please? Clin Rev. 2016;26(4):10,13-14.

2. Barker ER, Pittman O. Becoming a super preceptor: a practical guide to preceptorship in today’s clinical climate. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2010;22(3):144-149.

3. Levy BT, Gjerde CL, Albrecht LA. The effects of precepting on and the support desired by community-based preceptors in Iowa. Acad Med. 1997;72(5):382-384.

4. Logan BL, Kovacs KA, Barry TL. Precepting nurse practitioner students: one medical center’s efforts to improve the precepting process. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(12):676-682.

5. Aktan NM. Clinical preceptoring: what’s in it for me? J Nurse Pract. 2010;6(2):159-160.

Randy Danielsen’s editorial on the topic of precepting (April 2016) elicited a flurry of responses from our NP readers.1 The influx of feedback prompted me as an educator, an NP, and a former preceptor to wonder: Why the paucity of preceptors? Are there too many programs and too many students? And are we dropping the ball when it comes to engendering professional responsibility as a “social contract”?1

Let me start with a query: Are we requiring students to uphold their social contracts? That is, are they engaged in professional networking to enrich their own clinical experiences? Are they responsible for establishing relationships with providers in their communities in preparation for clinical rotations? Aren’t these all components of their social contracts as students?

In my PNP program, we found our own preceptors (there were no clinical coordinators “back in the day”). As a component of that, we often had to educate our preceptors on the role of the NP. Thankfully, the pediatric community was aware of the NP; in the Boston area, at least, many settings already had NPs (and PAs) as providers. Still, when I reflect back, the experience of finding a preceptor augmented my professional education. It also instilled in me responsibility for my own professional development.

When it was my turn, I agreed to precept as my contribution to the profession. However, my first foray into precepting was not a pleasant one. As some of our email authors attested to experiencing, my student was completely unprepared for her clinical rotation. I found myself teaching basic assessment skills (to a student in her final semester!), which takes considerable time in the office setting. Subsequently, I required students to have at least three years of RN experience and demonstrate a full H&P prior to acceptance. This proviso raised some eyebrows among my colleagues, but as I saw it, my role as a preceptor was to help students to improve their skills—not teach them the basics. The result: a happy preceptor and long-standing relationships with the precepted students.

Even so, like many of the clinicians who responded to Dr. Danielsen’s editorial, I must admit I eventually stopped precepting. My decision was based on several factors, but the primary reason was that the students and faculty recruiting me were somewhat cavalier in their responsibility for preparedness to practice.

Among the readers who shared their precepting experiences, many cited inexperience in the RN role as a significant issue, as well as the rapidity with which students progress through their NP programs. Some commented that there is too much material to understand and process and not enough time to master the skills. These observations lead me back to the idea of “too many programs and students.” I know I risk offending my colleagues in academia with that statement. But I also know, from conversations with colleagues and the volume of emails we received on this topic, that many preceptors are frustrated by some students’ lack of responsibility, motivation, and preparation for their clinical rotations.

Some chalk up this shortcoming to being “millennials.” Others suggest that online programs do not hold students accountable for the “real world” demands of the job. On the latter point, I would submit that the “brick and mortar” programs have similar issues with students. And while both of these points have some validity, I think the problem is more complicated.

We face a perfect storm in NP education: The demand for NPs has increased as a result of the implementation of the ACA. In response to this demand, the number of NP programs has grown, and so has the need for NP preceptors. Yet, at this critical time, the number of preceptors is dwindling (in volume, yes, but also in willingness).

To resolve this conundrum, we must take a closer look at ways we can reverse the declining interest in preceptorship. Increasing the number of available preceptors requires overcoming perceived barriers. One of these, as noted by Barker and Pittman, is the detrimental effect precepting has on productivity.2 To illustrate this, they presented findings from a study of community physicians that documented an increase in the time taken to see patients and a decrease in the number of patients seen when the physician was precepting students.3 Additional time and reduced productivity are not tolerated in today’s work environment, and patients, who increasingly see themselves as health care consumers (who can take their “business” elsewhere), don’t appreciate waiting to see their health care provider when they have an appointment.

In their research, Logan, Kovacs, and Barry also found that productivity expectations (or should I say, the expectation of reduced productivity) impeded willingness to precept.4 They identified lack of time in the workday as a major barrier. This point is difficult to counter, I admit. But they also presented two other deterrents that, conversely, I view as potential opportunities for increasing the number of willing preceptors:

Lack of training for preceptors. Preceptors must learn how to fulfill this role on their own, without any training or support. This is a significant problem, not only for nascent preceptors but also for seasoned ones, who often precept students from different programs with a variety of requirements and expectations (and paperwork!). In an editorial, a new preceptor expressed concern about her ability to “get it right” and give her student what was needed to accomplish the goals for the rotation.5 Training and supportive testimonies are essential for successful precepting. A simple approach would be for program faculty to “mentor” new preceptors: Spend time orienting them to the expectations of the program and explaining how to evaluate students. Be proactive—establish weekly conference calls and share both strategies for successful precepting relationships and the “pitfalls to avoid.”

Student preparation. The other problem discussed by Logan, Kovacs, and Barry—and attested to by many of our readers—was the skill level and readiness of students on the first day of their clinical experience. While this responsibility lies with the student (rightfully so), I believe awareness of this problem, and understanding of how it affects practitioners’ willingness to precept, offers an opportunity for our education programs. Students may not know what they don’t know, or some may be too timid to speak up if they feel unprepared to step into a clinical arena (not to confuse that unease with “first-day jitters”). It is incumbent on the program faculty to ensure their students—who are representatives of that program and the faculty—are ready for clinical rotations. What do they need to do? Conduct an assessment of skills and readiness, which would assist all parties—the student, the preceptor, and the faculty—in gauging the progress of skill improvement and student competency and capability as a provider. It is also imperative that any remediation be provided by the program (prior to the student’s entrance into the clinical setting) and not the preceptor.

The bottom line is that precepting is a partnership between the skilled practitioner, the NP faculty, and the focused student.2 The responsibility for a mutually enjoyable and rewarding experience lies with all parties involved. As seasoned NPs, we must be active participants in preparing the next generation of our colleagues. That is our professional responsibility—our fulfillment of the “social contract.” We owe it to them, we owe it to our patients, and we owe it to ourselves—because someday, down the road, these clinicians will be taking care of us!

When a topic merits two editorials, there is clearly much to discuss. What steps do you suggest we undertake to mitigate this conundrum? Share your ideas by writing to me at NPEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Danielsen RD. The death of altruism, or, can I get a preceptor please? Clin Rev. 2016;26(4):10,13-14.

2. Barker ER, Pittman O. Becoming a super preceptor: a practical guide to preceptorship in today’s clinical climate. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2010;22(3):144-149.

3. Levy BT, Gjerde CL, Albrecht LA. The effects of precepting on and the support desired by community-based preceptors in Iowa. Acad Med. 1997;72(5):382-384.

4. Logan BL, Kovacs KA, Barry TL. Precepting nurse practitioner students: one medical center’s efforts to improve the precepting process. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(12):676-682.

5. Aktan NM. Clinical preceptoring: what’s in it for me? J Nurse Pract. 2010;6(2):159-160.

Randy Danielsen’s editorial on the topic of precepting (April 2016) elicited a flurry of responses from our NP readers.1 The influx of feedback prompted me as an educator, an NP, and a former preceptor to wonder: Why the paucity of preceptors? Are there too many programs and too many students? And are we dropping the ball when it comes to engendering professional responsibility as a “social contract”?1

Let me start with a query: Are we requiring students to uphold their social contracts? That is, are they engaged in professional networking to enrich their own clinical experiences? Are they responsible for establishing relationships with providers in their communities in preparation for clinical rotations? Aren’t these all components of their social contracts as students?

In my PNP program, we found our own preceptors (there were no clinical coordinators “back in the day”). As a component of that, we often had to educate our preceptors on the role of the NP. Thankfully, the pediatric community was aware of the NP; in the Boston area, at least, many settings already had NPs (and PAs) as providers. Still, when I reflect back, the experience of finding a preceptor augmented my professional education. It also instilled in me responsibility for my own professional development.

When it was my turn, I agreed to precept as my contribution to the profession. However, my first foray into precepting was not a pleasant one. As some of our email authors attested to experiencing, my student was completely unprepared for her clinical rotation. I found myself teaching basic assessment skills (to a student in her final semester!), which takes considerable time in the office setting. Subsequently, I required students to have at least three years of RN experience and demonstrate a full H&P prior to acceptance. This proviso raised some eyebrows among my colleagues, but as I saw it, my role as a preceptor was to help students to improve their skills—not teach them the basics. The result: a happy preceptor and long-standing relationships with the precepted students.

Even so, like many of the clinicians who responded to Dr. Danielsen’s editorial, I must admit I eventually stopped precepting. My decision was based on several factors, but the primary reason was that the students and faculty recruiting me were somewhat cavalier in their responsibility for preparedness to practice.

Among the readers who shared their precepting experiences, many cited inexperience in the RN role as a significant issue, as well as the rapidity with which students progress through their NP programs. Some commented that there is too much material to understand and process and not enough time to master the skills. These observations lead me back to the idea of “too many programs and students.” I know I risk offending my colleagues in academia with that statement. But I also know, from conversations with colleagues and the volume of emails we received on this topic, that many preceptors are frustrated by some students’ lack of responsibility, motivation, and preparation for their clinical rotations.

Some chalk up this shortcoming to being “millennials.” Others suggest that online programs do not hold students accountable for the “real world” demands of the job. On the latter point, I would submit that the “brick and mortar” programs have similar issues with students. And while both of these points have some validity, I think the problem is more complicated.

We face a perfect storm in NP education: The demand for NPs has increased as a result of the implementation of the ACA. In response to this demand, the number of NP programs has grown, and so has the need for NP preceptors. Yet, at this critical time, the number of preceptors is dwindling (in volume, yes, but also in willingness).

To resolve this conundrum, we must take a closer look at ways we can reverse the declining interest in preceptorship. Increasing the number of available preceptors requires overcoming perceived barriers. One of these, as noted by Barker and Pittman, is the detrimental effect precepting has on productivity.2 To illustrate this, they presented findings from a study of community physicians that documented an increase in the time taken to see patients and a decrease in the number of patients seen when the physician was precepting students.3 Additional time and reduced productivity are not tolerated in today’s work environment, and patients, who increasingly see themselves as health care consumers (who can take their “business” elsewhere), don’t appreciate waiting to see their health care provider when they have an appointment.

In their research, Logan, Kovacs, and Barry also found that productivity expectations (or should I say, the expectation of reduced productivity) impeded willingness to precept.4 They identified lack of time in the workday as a major barrier. This point is difficult to counter, I admit. But they also presented two other deterrents that, conversely, I view as potential opportunities for increasing the number of willing preceptors:

Lack of training for preceptors. Preceptors must learn how to fulfill this role on their own, without any training or support. This is a significant problem, not only for nascent preceptors but also for seasoned ones, who often precept students from different programs with a variety of requirements and expectations (and paperwork!). In an editorial, a new preceptor expressed concern about her ability to “get it right” and give her student what was needed to accomplish the goals for the rotation.5 Training and supportive testimonies are essential for successful precepting. A simple approach would be for program faculty to “mentor” new preceptors: Spend time orienting them to the expectations of the program and explaining how to evaluate students. Be proactive—establish weekly conference calls and share both strategies for successful precepting relationships and the “pitfalls to avoid.”

Student preparation. The other problem discussed by Logan, Kovacs, and Barry—and attested to by many of our readers—was the skill level and readiness of students on the first day of their clinical experience. While this responsibility lies with the student (rightfully so), I believe awareness of this problem, and understanding of how it affects practitioners’ willingness to precept, offers an opportunity for our education programs. Students may not know what they don’t know, or some may be too timid to speak up if they feel unprepared to step into a clinical arena (not to confuse that unease with “first-day jitters”). It is incumbent on the program faculty to ensure their students—who are representatives of that program and the faculty—are ready for clinical rotations. What do they need to do? Conduct an assessment of skills and readiness, which would assist all parties—the student, the preceptor, and the faculty—in gauging the progress of skill improvement and student competency and capability as a provider. It is also imperative that any remediation be provided by the program (prior to the student’s entrance into the clinical setting) and not the preceptor.

The bottom line is that precepting is a partnership between the skilled practitioner, the NP faculty, and the focused student.2 The responsibility for a mutually enjoyable and rewarding experience lies with all parties involved. As seasoned NPs, we must be active participants in preparing the next generation of our colleagues. That is our professional responsibility—our fulfillment of the “social contract.” We owe it to them, we owe it to our patients, and we owe it to ourselves—because someday, down the road, these clinicians will be taking care of us!

When a topic merits two editorials, there is clearly much to discuss. What steps do you suggest we undertake to mitigate this conundrum? Share your ideas by writing to me at NPEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Danielsen RD. The death of altruism, or, can I get a preceptor please? Clin Rev. 2016;26(4):10,13-14.

2. Barker ER, Pittman O. Becoming a super preceptor: a practical guide to preceptorship in today’s clinical climate. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2010;22(3):144-149.

3. Levy BT, Gjerde CL, Albrecht LA. The effects of precepting on and the support desired by community-based preceptors in Iowa. Acad Med. 1997;72(5):382-384.

4. Logan BL, Kovacs KA, Barry TL. Precepting nurse practitioner students: one medical center’s efforts to improve the precepting process. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(12):676-682.

5. Aktan NM. Clinical preceptoring: what’s in it for me? J Nurse Pract. 2010;6(2):159-160.

The ACA, Six Years Later …

On March 23, 2016, we recognized the sixth anniversary of the signing of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), a law designed to increase the number of Americans covered by health insurance and decrease the cost of health care. Prior to and since its passage, many have criticized the ACA as too costly and too quickly implemented (indeed, some would say, implemented without much planning or thought). Others have denigrated it as a step toward “socialized medicine” or as “big government”—a historically distrusted approach to solving problems.

As a student of health policy, I have watched the yarn of attempts to enact a comprehensive health insurance system ravel and unravel with each administration. Yes, for decades, political parties have staunchly opposed this type of program to reform our ailing system. But why is there such resistance to government involvement in health care reform?

This hasn’t been limited to insurance. Since the mid-1800s, despite the known dangers (including death) of various contagious diseases (eg, smallpox, malaria), people have resisted, even vehemently opposed, government-initiated regulations intended to combat such illnesses.1 Yet, today, we recognize that many improvements in the health of our communities and ourselves are founded on the infrastructure of the public health system. In most cities and states, the public health department responds to everyday health threats and emergencies through programs and initiatives that are government sponsored and funded—and accepted (one might even say expected) by most of us. Dare I point out that these are part of a “social insurance” program?

The idea of a comprehensive approach to health care coverage is not new. One of the earliest government interventions toward social insurance was the 1921 Sheppard-Towner Act, which provided matching funds to states for prenatal and child health centers. Regrettably, it was viewed by the AMA as “excessive federal interference in local health concerns” and discontinued a mere six years later.1

A later intervention, the Hill-Burton Act (passed in 1946) provided hospitals, nursing homes, and other health facilities with grants and loans for construction and modernization.2 An obligation tied to receiving funds was the requirement that administrators of the facilities “provide a reasonable volume of services to persons unable to pay and to make their services available to all persons residing in the facility’s area.”2 One could posit that these two policies influenced the movement toward national insurance in the United States.

We have a patchwork quilt of a health insurance system that includes social insurance programs: Social Security and Medicare. Generations of Americans have contributed to those programs through taxes and expect to benefit from them. And for generations—actually a century—there have been attempts to establish national health insurance (NHI) in the US. In the early 1900s, after Germany and England established health insurance for industrial workers, progressive social reformers attempted to secure similar protection for American workers but were unsuccessful.3 Repeated efforts in 1948, 1965, 1974, 1978, and 1994 also failed to institute an NHI program.

But why? There has been public support for some form of comprehensive NHI since the 1930s. The percentage of Americans expressing support for more government intervention on health care delivery has not fallen below 60% since 1937.4 This disconnect between the people’s desires and politics has been analyzed extensively and written about in many health policy texts.

So when did the idea of NHI become palatable? The notion came closer to reality during the Clinton administration. As the political parties began to fragment, they lost their power over health care politics. With more than 30 million Americans either without health insurance, or in jeopardy of losing what they had, the push for reform was stronger than ever before. We came close, but the scare tactics by NHI opponents about cost, decreased benefits, and increased risk (remember the Harry and Louise commercials?) quickly put the kibosh on that attempt at reform.

Continue forward to 2009 >>

Fast forward to 2009: Barack Obama is elected president and upholds his stance on health care reform, with a vow to institute a universal or near-universal health insurance program during his administration. As he said in his remarks to Congress, “I am not the first President to take up this cause [the issue of health care], but I am determined to be the last.”5 Hearing that an NHI program would cost $900 billion over 10 years was a bitter pill to swallow for some.5 But we couldn’t afford not to undertake it.

Since the enactment of the ACA, 18 million uninsured people have gained health coverage.6 The law has also improved access to health care services provided by NPs and PAs, evidenced by the nondiscrimination provision acknowledging us as primary care providers. The shortage of physicians and the increase in the number of newly insured persons seeking health care created an unprecedented opportunity to increase the utilization of NPs and PAs throughout the health care system.

Reflecting on the cost of the ACA, I have always maintained two positions: First, we pay for health care at often the most expensive place (the ED) or time (end-stage disease) … so it is a case of “pay me now or pay me later.” Second, we must gain control over the overall cost of health care. Providing access to primary care services for everyone is a step toward getting that control.

I have been a supporter of an NHI system all my adult life. I consider myself lucky to have had continuous access to health care. But I have cared for many who have not been so fortunate, and I have seen a minor illness become a major event because the family has no access to care. Without universal access to care, these cases increase—and with them, the cost of care.

Is the ACA the perfect solution? Even six years later, I think the jury is still out. But what I know for sure is that it was the first step in the right direction. You no doubt have opinions on this topic; please share them with me at NPEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Heinrich J. Organization and delivery of health care in the United States: the health care system that isn’t. In: Mason DJ, Leavitt JK, eds. Policy and Politics in Nursing and Health Care. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1998:59-79.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Hill-Burton Program (July 2010). www.hrsa.gov/gethealthcare/affordable/hillburton/hillburton.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2016.

3. Altman S, Schactman D. Power, Politics, and Universal Health Care: The Inside Story of a Century-long Battle. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books; 2011.

4. Steinmo S, Watts J. It’s the institutions, stupid: why comprehensive national health insurance always fails in America. In: Harrington C, Estes CL, eds. Health Policy: Crisis and Reform in the US Health Care Delivery System. 5th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2008:30-36.

5. White House Office of the Press Secretary. Remarks by the President to a Joint Session of Congress on Health Care, September 9, 2009. www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-a-joint-session-congress-health-care. Accessed April 11, 2016.

6. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, September 2015. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-insurance-coverage-and-affordable-care-act-september-2015. Accessed April 11, 2016.

On March 23, 2016, we recognized the sixth anniversary of the signing of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), a law designed to increase the number of Americans covered by health insurance and decrease the cost of health care. Prior to and since its passage, many have criticized the ACA as too costly and too quickly implemented (indeed, some would say, implemented without much planning or thought). Others have denigrated it as a step toward “socialized medicine” or as “big government”—a historically distrusted approach to solving problems.

As a student of health policy, I have watched the yarn of attempts to enact a comprehensive health insurance system ravel and unravel with each administration. Yes, for decades, political parties have staunchly opposed this type of program to reform our ailing system. But why is there such resistance to government involvement in health care reform?

This hasn’t been limited to insurance. Since the mid-1800s, despite the known dangers (including death) of various contagious diseases (eg, smallpox, malaria), people have resisted, even vehemently opposed, government-initiated regulations intended to combat such illnesses.1 Yet, today, we recognize that many improvements in the health of our communities and ourselves are founded on the infrastructure of the public health system. In most cities and states, the public health department responds to everyday health threats and emergencies through programs and initiatives that are government sponsored and funded—and accepted (one might even say expected) by most of us. Dare I point out that these are part of a “social insurance” program?

The idea of a comprehensive approach to health care coverage is not new. One of the earliest government interventions toward social insurance was the 1921 Sheppard-Towner Act, which provided matching funds to states for prenatal and child health centers. Regrettably, it was viewed by the AMA as “excessive federal interference in local health concerns” and discontinued a mere six years later.1

A later intervention, the Hill-Burton Act (passed in 1946) provided hospitals, nursing homes, and other health facilities with grants and loans for construction and modernization.2 An obligation tied to receiving funds was the requirement that administrators of the facilities “provide a reasonable volume of services to persons unable to pay and to make their services available to all persons residing in the facility’s area.”2 One could posit that these two policies influenced the movement toward national insurance in the United States.

We have a patchwork quilt of a health insurance system that includes social insurance programs: Social Security and Medicare. Generations of Americans have contributed to those programs through taxes and expect to benefit from them. And for generations—actually a century—there have been attempts to establish national health insurance (NHI) in the US. In the early 1900s, after Germany and England established health insurance for industrial workers, progressive social reformers attempted to secure similar protection for American workers but were unsuccessful.3 Repeated efforts in 1948, 1965, 1974, 1978, and 1994 also failed to institute an NHI program.

But why? There has been public support for some form of comprehensive NHI since the 1930s. The percentage of Americans expressing support for more government intervention on health care delivery has not fallen below 60% since 1937.4 This disconnect between the people’s desires and politics has been analyzed extensively and written about in many health policy texts.

So when did the idea of NHI become palatable? The notion came closer to reality during the Clinton administration. As the political parties began to fragment, they lost their power over health care politics. With more than 30 million Americans either without health insurance, or in jeopardy of losing what they had, the push for reform was stronger than ever before. We came close, but the scare tactics by NHI opponents about cost, decreased benefits, and increased risk (remember the Harry and Louise commercials?) quickly put the kibosh on that attempt at reform.

Continue forward to 2009 >>

Fast forward to 2009: Barack Obama is elected president and upholds his stance on health care reform, with a vow to institute a universal or near-universal health insurance program during his administration. As he said in his remarks to Congress, “I am not the first President to take up this cause [the issue of health care], but I am determined to be the last.”5 Hearing that an NHI program would cost $900 billion over 10 years was a bitter pill to swallow for some.5 But we couldn’t afford not to undertake it.

Since the enactment of the ACA, 18 million uninsured people have gained health coverage.6 The law has also improved access to health care services provided by NPs and PAs, evidenced by the nondiscrimination provision acknowledging us as primary care providers. The shortage of physicians and the increase in the number of newly insured persons seeking health care created an unprecedented opportunity to increase the utilization of NPs and PAs throughout the health care system.

Reflecting on the cost of the ACA, I have always maintained two positions: First, we pay for health care at often the most expensive place (the ED) or time (end-stage disease) … so it is a case of “pay me now or pay me later.” Second, we must gain control over the overall cost of health care. Providing access to primary care services for everyone is a step toward getting that control.

I have been a supporter of an NHI system all my adult life. I consider myself lucky to have had continuous access to health care. But I have cared for many who have not been so fortunate, and I have seen a minor illness become a major event because the family has no access to care. Without universal access to care, these cases increase—and with them, the cost of care.

Is the ACA the perfect solution? Even six years later, I think the jury is still out. But what I know for sure is that it was the first step in the right direction. You no doubt have opinions on this topic; please share them with me at NPEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Heinrich J. Organization and delivery of health care in the United States: the health care system that isn’t. In: Mason DJ, Leavitt JK, eds. Policy and Politics in Nursing and Health Care. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1998:59-79.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Hill-Burton Program (July 2010). www.hrsa.gov/gethealthcare/affordable/hillburton/hillburton.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2016.

3. Altman S, Schactman D. Power, Politics, and Universal Health Care: The Inside Story of a Century-long Battle. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books; 2011.

4. Steinmo S, Watts J. It’s the institutions, stupid: why comprehensive national health insurance always fails in America. In: Harrington C, Estes CL, eds. Health Policy: Crisis and Reform in the US Health Care Delivery System. 5th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2008:30-36.

5. White House Office of the Press Secretary. Remarks by the President to a Joint Session of Congress on Health Care, September 9, 2009. www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-a-joint-session-congress-health-care. Accessed April 11, 2016.

6. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, September 2015. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-insurance-coverage-and-affordable-care-act-september-2015. Accessed April 11, 2016.

On March 23, 2016, we recognized the sixth anniversary of the signing of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), a law designed to increase the number of Americans covered by health insurance and decrease the cost of health care. Prior to and since its passage, many have criticized the ACA as too costly and too quickly implemented (indeed, some would say, implemented without much planning or thought). Others have denigrated it as a step toward “socialized medicine” or as “big government”—a historically distrusted approach to solving problems.

As a student of health policy, I have watched the yarn of attempts to enact a comprehensive health insurance system ravel and unravel with each administration. Yes, for decades, political parties have staunchly opposed this type of program to reform our ailing system. But why is there such resistance to government involvement in health care reform?

This hasn’t been limited to insurance. Since the mid-1800s, despite the known dangers (including death) of various contagious diseases (eg, smallpox, malaria), people have resisted, even vehemently opposed, government-initiated regulations intended to combat such illnesses.1 Yet, today, we recognize that many improvements in the health of our communities and ourselves are founded on the infrastructure of the public health system. In most cities and states, the public health department responds to everyday health threats and emergencies through programs and initiatives that are government sponsored and funded—and accepted (one might even say expected) by most of us. Dare I point out that these are part of a “social insurance” program?

The idea of a comprehensive approach to health care coverage is not new. One of the earliest government interventions toward social insurance was the 1921 Sheppard-Towner Act, which provided matching funds to states for prenatal and child health centers. Regrettably, it was viewed by the AMA as “excessive federal interference in local health concerns” and discontinued a mere six years later.1

A later intervention, the Hill-Burton Act (passed in 1946) provided hospitals, nursing homes, and other health facilities with grants and loans for construction and modernization.2 An obligation tied to receiving funds was the requirement that administrators of the facilities “provide a reasonable volume of services to persons unable to pay and to make their services available to all persons residing in the facility’s area.”2 One could posit that these two policies influenced the movement toward national insurance in the United States.

We have a patchwork quilt of a health insurance system that includes social insurance programs: Social Security and Medicare. Generations of Americans have contributed to those programs through taxes and expect to benefit from them. And for generations—actually a century—there have been attempts to establish national health insurance (NHI) in the US. In the early 1900s, after Germany and England established health insurance for industrial workers, progressive social reformers attempted to secure similar protection for American workers but were unsuccessful.3 Repeated efforts in 1948, 1965, 1974, 1978, and 1994 also failed to institute an NHI program.

But why? There has been public support for some form of comprehensive NHI since the 1930s. The percentage of Americans expressing support for more government intervention on health care delivery has not fallen below 60% since 1937.4 This disconnect between the people’s desires and politics has been analyzed extensively and written about in many health policy texts.

So when did the idea of NHI become palatable? The notion came closer to reality during the Clinton administration. As the political parties began to fragment, they lost their power over health care politics. With more than 30 million Americans either without health insurance, or in jeopardy of losing what they had, the push for reform was stronger than ever before. We came close, but the scare tactics by NHI opponents about cost, decreased benefits, and increased risk (remember the Harry and Louise commercials?) quickly put the kibosh on that attempt at reform.

Continue forward to 2009 >>

Fast forward to 2009: Barack Obama is elected president and upholds his stance on health care reform, with a vow to institute a universal or near-universal health insurance program during his administration. As he said in his remarks to Congress, “I am not the first President to take up this cause [the issue of health care], but I am determined to be the last.”5 Hearing that an NHI program would cost $900 billion over 10 years was a bitter pill to swallow for some.5 But we couldn’t afford not to undertake it.

Since the enactment of the ACA, 18 million uninsured people have gained health coverage.6 The law has also improved access to health care services provided by NPs and PAs, evidenced by the nondiscrimination provision acknowledging us as primary care providers. The shortage of physicians and the increase in the number of newly insured persons seeking health care created an unprecedented opportunity to increase the utilization of NPs and PAs throughout the health care system.

Reflecting on the cost of the ACA, I have always maintained two positions: First, we pay for health care at often the most expensive place (the ED) or time (end-stage disease) … so it is a case of “pay me now or pay me later.” Second, we must gain control over the overall cost of health care. Providing access to primary care services for everyone is a step toward getting that control.

I have been a supporter of an NHI system all my adult life. I consider myself lucky to have had continuous access to health care. But I have cared for many who have not been so fortunate, and I have seen a minor illness become a major event because the family has no access to care. Without universal access to care, these cases increase—and with them, the cost of care.

Is the ACA the perfect solution? Even six years later, I think the jury is still out. But what I know for sure is that it was the first step in the right direction. You no doubt have opinions on this topic; please share them with me at NPEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Heinrich J. Organization and delivery of health care in the United States: the health care system that isn’t. In: Mason DJ, Leavitt JK, eds. Policy and Politics in Nursing and Health Care. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1998:59-79.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Hill-Burton Program (July 2010). www.hrsa.gov/gethealthcare/affordable/hillburton/hillburton.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2016.

3. Altman S, Schactman D. Power, Politics, and Universal Health Care: The Inside Story of a Century-long Battle. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books; 2011.

4. Steinmo S, Watts J. It’s the institutions, stupid: why comprehensive national health insurance always fails in America. In: Harrington C, Estes CL, eds. Health Policy: Crisis and Reform in the US Health Care Delivery System. 5th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2008:30-36.

5. White House Office of the Press Secretary. Remarks by the President to a Joint Session of Congress on Health Care, September 9, 2009. www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-a-joint-session-congress-health-care. Accessed April 11, 2016.

6. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, September 2015. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-insurance-coverage-and-affordable-care-act-september-2015. Accessed April 11, 2016.

Scholars in Solitude

Recently, six faculty colleagues and I were discussing socialization of students in distance-learning programs. Each of us shared concerns that had been voiced by students regarding the periods of isolation they frequently feel while studying or completing course assignments. The common theme was expressed as “not feeling connected” and “no real camaraderie” with fellow students. One of us also raised the issue of internal conflict; a student had described herself as enjoying the freedom to listen to lectures on her own schedule and not be obligated to attend class on a specific day at a specific time but simultaneously missing seeing her classmates on a weekly basis.

For the most part, my colleagues and I were all “bricks and mortar” students, tied to required attendance during scheduled classes. We collectively agreed that this was frequently a bother, but we recognized the advantage of being able to sit together before or after class to discuss assignments, bring clarity to confusion, or simply commiserate on the difficulties of balancing family, school, and work obligations. In my own doctoral studies, week-to-week support and encouragement kept us a close-knit group, seeing us through to completed dissertations.

As our conversation continued, we began to lament our own lack of connectedness, not to our students (we communicate with them at least, if not more than, once a week) but to our faculty colleagues. Our consensus was that the focus on student-to-faculty contact left faculty-to-faculty contact seemingly an afterthought—or not a thought at all. I consider myself lucky that most of “my faculty” were friends or professional colleagues prior to our academic postings. Thus, we had established relationships outside our faculty roles.

But this whole idea of the socialization of faculty in distance education got me wondering: Are there criteria or guidelines for communication among faculty? I don’t mean the required staff meetings; I mean something similar to the requirements for type, and frequency, of interactions with the students, which are set forth by credentialing entities. I wondered what I could find in the literature or educational texts about faculty “connectedness.” And so my search began.

Continue for where my search began >>

I started with Keating’s text,1 the table of contents of which listed a chapter on Distance Education. Hmm, I thought, there must be something there. Several sections were enlightening and could very easily provide guidance for faculty-student interactions, but not so much for faculty to faculty. Granted, the basis for the text is curriculum development, so I am not denigrating the work; I just hoped a chapter on program development would include something on developing faculty networks.

As my search continued, I found the Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. Notable was research presented by Bower,2 who described findings of an American Faculty Poll conducted in 2000 noting that “direct engagement with the students is one of the most important factors” in an educator’s decision to pursue an academic career.3 In this poll, a flexible work schedule was viewed as very important by 60% of those surveyed; those of us who are engaged in distance education have the most control (I would submit) over our schedules. But there was no evidence that faculty who taught online were represented in that survey—and no discussion of faculty-to-faculty connections.

Despite repeated searches, I found a paucity of research regarding socialization (or lack thereof) among faculty teaching in the online environment. In her dissertation, Heilman4 addressed perceptions of satisfaction with online teaching. One element she researched was faculty/peer relationships. Her participants noted that “networking and sharing with other online faculty members who work in another location” enhanced their satisfaction, but several noted that “lack of interactions or feeling isolated from their peers” diminished their satisfaction with online teaching. In reading their comments, I formed the impression that the interactions were initiated by the individual faculty, rather than facilitated by the institution.

Recently, I have seen blog posts addressing the issue of transforming clinicians to academics. There is a universal understanding that being an expert clinician does not necessarily mean you are a proficient educator. Moreover, transitioning from a face-to-face system to an online environment can be intimidating. Faculty, especially those new to the role, may need additional support.

Having an internal social network for online faculty is a means to achieving a supportive community and building a mentoring culture within an institution. A faculty member who has a sense of connectedness to other faculty (onsite and online) is as important to the successful online environment as is the development of a sense of community for students. The community must serve to enhance learning and teaching for both groups.

There are several published guidelines for successful online teaching—that is, what faculty can do for students. I have taken those principles, modified them, and applied them as suggestions for improving the socialization of faculty. With recognition of those who devised them5,6 and acknowledgement of the poetic license applied, here they are:

• Encourage faculty-to-faculty contact outside mandatory meetings

• Encourage faculty collaboration beyond course/institutional requirements

• Provide for live, interactive events that are fun.

With the ever-increasing number of educational institutions providing online programs (now at about 89%7), it is imperative that we as faculty and program administrators include socialization as a component of faculty orientation and training. What better than a connected faculty to enhance student achievement?

When we’re on site, my faculty colleagues and I plan dinner together. During commencement week, laughter and camaraderie from “unofficial” social activities allow us to relax, celebrate another successful class, and form memories that we carry with us throughout the year. What about your institutions? Please share your ideas about “staying connected” to colleagues in a digital environment by writing to NPEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Keating SB. Curriculum Development and Evaluation in Nursing. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006.

2. Bower BL. Distance education: facing the faculty challenge. Online J Distance Learning Admin. 2001;4(2).

3. Sanderson A, Phua VC, Herda D. The American Faculty Poll. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center; 2000.

4. Heilman JG. Higher education faculty satisfaction with online teaching [dissertation]. 2007. http://hdl.handle.net/2152/3796. Accessed February 15, 2016.

5. Koeckeritz J, Malkiewicz J, Henderson A. The seven principles of good practice: applications for online education in nursing. Nurse Educ. 2002;27(6):283-287.

6. Chickering AW, Gamson ZF. Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin. 1987;39(7):3-7.

7. Parker K, Lenhart A, Moore K. The Digital Revolution and Higher Education: College Presidents, Public Differ on Value of Online Learning. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2011.

Recently, six faculty colleagues and I were discussing socialization of students in distance-learning programs. Each of us shared concerns that had been voiced by students regarding the periods of isolation they frequently feel while studying or completing course assignments. The common theme was expressed as “not feeling connected” and “no real camaraderie” with fellow students. One of us also raised the issue of internal conflict; a student had described herself as enjoying the freedom to listen to lectures on her own schedule and not be obligated to attend class on a specific day at a specific time but simultaneously missing seeing her classmates on a weekly basis.

For the most part, my colleagues and I were all “bricks and mortar” students, tied to required attendance during scheduled classes. We collectively agreed that this was frequently a bother, but we recognized the advantage of being able to sit together before or after class to discuss assignments, bring clarity to confusion, or simply commiserate on the difficulties of balancing family, school, and work obligations. In my own doctoral studies, week-to-week support and encouragement kept us a close-knit group, seeing us through to completed dissertations.

As our conversation continued, we began to lament our own lack of connectedness, not to our students (we communicate with them at least, if not more than, once a week) but to our faculty colleagues. Our consensus was that the focus on student-to-faculty contact left faculty-to-faculty contact seemingly an afterthought—or not a thought at all. I consider myself lucky that most of “my faculty” were friends or professional colleagues prior to our academic postings. Thus, we had established relationships outside our faculty roles.

But this whole idea of the socialization of faculty in distance education got me wondering: Are there criteria or guidelines for communication among faculty? I don’t mean the required staff meetings; I mean something similar to the requirements for type, and frequency, of interactions with the students, which are set forth by credentialing entities. I wondered what I could find in the literature or educational texts about faculty “connectedness.” And so my search began.

Continue for where my search began >>

I started with Keating’s text,1 the table of contents of which listed a chapter on Distance Education. Hmm, I thought, there must be something there. Several sections were enlightening and could very easily provide guidance for faculty-student interactions, but not so much for faculty to faculty. Granted, the basis for the text is curriculum development, so I am not denigrating the work; I just hoped a chapter on program development would include something on developing faculty networks.

As my search continued, I found the Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. Notable was research presented by Bower,2 who described findings of an American Faculty Poll conducted in 2000 noting that “direct engagement with the students is one of the most important factors” in an educator’s decision to pursue an academic career.3 In this poll, a flexible work schedule was viewed as very important by 60% of those surveyed; those of us who are engaged in distance education have the most control (I would submit) over our schedules. But there was no evidence that faculty who taught online were represented in that survey—and no discussion of faculty-to-faculty connections.

Despite repeated searches, I found a paucity of research regarding socialization (or lack thereof) among faculty teaching in the online environment. In her dissertation, Heilman4 addressed perceptions of satisfaction with online teaching. One element she researched was faculty/peer relationships. Her participants noted that “networking and sharing with other online faculty members who work in another location” enhanced their satisfaction, but several noted that “lack of interactions or feeling isolated from their peers” diminished their satisfaction with online teaching. In reading their comments, I formed the impression that the interactions were initiated by the individual faculty, rather than facilitated by the institution.

Recently, I have seen blog posts addressing the issue of transforming clinicians to academics. There is a universal understanding that being an expert clinician does not necessarily mean you are a proficient educator. Moreover, transitioning from a face-to-face system to an online environment can be intimidating. Faculty, especially those new to the role, may need additional support.

Having an internal social network for online faculty is a means to achieving a supportive community and building a mentoring culture within an institution. A faculty member who has a sense of connectedness to other faculty (onsite and online) is as important to the successful online environment as is the development of a sense of community for students. The community must serve to enhance learning and teaching for both groups.

There are several published guidelines for successful online teaching—that is, what faculty can do for students. I have taken those principles, modified them, and applied them as suggestions for improving the socialization of faculty. With recognition of those who devised them5,6 and acknowledgement of the poetic license applied, here they are:

• Encourage faculty-to-faculty contact outside mandatory meetings

• Encourage faculty collaboration beyond course/institutional requirements

• Provide for live, interactive events that are fun.

With the ever-increasing number of educational institutions providing online programs (now at about 89%7), it is imperative that we as faculty and program administrators include socialization as a component of faculty orientation and training. What better than a connected faculty to enhance student achievement?

When we’re on site, my faculty colleagues and I plan dinner together. During commencement week, laughter and camaraderie from “unofficial” social activities allow us to relax, celebrate another successful class, and form memories that we carry with us throughout the year. What about your institutions? Please share your ideas about “staying connected” to colleagues in a digital environment by writing to NPEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Keating SB. Curriculum Development and Evaluation in Nursing. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006.

2. Bower BL. Distance education: facing the faculty challenge. Online J Distance Learning Admin. 2001;4(2).

3. Sanderson A, Phua VC, Herda D. The American Faculty Poll. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center; 2000.

4. Heilman JG. Higher education faculty satisfaction with online teaching [dissertation]. 2007. http://hdl.handle.net/2152/3796. Accessed February 15, 2016.

5. Koeckeritz J, Malkiewicz J, Henderson A. The seven principles of good practice: applications for online education in nursing. Nurse Educ. 2002;27(6):283-287.

6. Chickering AW, Gamson ZF. Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin. 1987;39(7):3-7.

7. Parker K, Lenhart A, Moore K. The Digital Revolution and Higher Education: College Presidents, Public Differ on Value of Online Learning. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2011.

Recently, six faculty colleagues and I were discussing socialization of students in distance-learning programs. Each of us shared concerns that had been voiced by students regarding the periods of isolation they frequently feel while studying or completing course assignments. The common theme was expressed as “not feeling connected” and “no real camaraderie” with fellow students. One of us also raised the issue of internal conflict; a student had described herself as enjoying the freedom to listen to lectures on her own schedule and not be obligated to attend class on a specific day at a specific time but simultaneously missing seeing her classmates on a weekly basis.

For the most part, my colleagues and I were all “bricks and mortar” students, tied to required attendance during scheduled classes. We collectively agreed that this was frequently a bother, but we recognized the advantage of being able to sit together before or after class to discuss assignments, bring clarity to confusion, or simply commiserate on the difficulties of balancing family, school, and work obligations. In my own doctoral studies, week-to-week support and encouragement kept us a close-knit group, seeing us through to completed dissertations.

As our conversation continued, we began to lament our own lack of connectedness, not to our students (we communicate with them at least, if not more than, once a week) but to our faculty colleagues. Our consensus was that the focus on student-to-faculty contact left faculty-to-faculty contact seemingly an afterthought—or not a thought at all. I consider myself lucky that most of “my faculty” were friends or professional colleagues prior to our academic postings. Thus, we had established relationships outside our faculty roles.

But this whole idea of the socialization of faculty in distance education got me wondering: Are there criteria or guidelines for communication among faculty? I don’t mean the required staff meetings; I mean something similar to the requirements for type, and frequency, of interactions with the students, which are set forth by credentialing entities. I wondered what I could find in the literature or educational texts about faculty “connectedness.” And so my search began.

Continue for where my search began >>

I started with Keating’s text,1 the table of contents of which listed a chapter on Distance Education. Hmm, I thought, there must be something there. Several sections were enlightening and could very easily provide guidance for faculty-student interactions, but not so much for faculty to faculty. Granted, the basis for the text is curriculum development, so I am not denigrating the work; I just hoped a chapter on program development would include something on developing faculty networks.

As my search continued, I found the Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. Notable was research presented by Bower,2 who described findings of an American Faculty Poll conducted in 2000 noting that “direct engagement with the students is one of the most important factors” in an educator’s decision to pursue an academic career.3 In this poll, a flexible work schedule was viewed as very important by 60% of those surveyed; those of us who are engaged in distance education have the most control (I would submit) over our schedules. But there was no evidence that faculty who taught online were represented in that survey—and no discussion of faculty-to-faculty connections.

Despite repeated searches, I found a paucity of research regarding socialization (or lack thereof) among faculty teaching in the online environment. In her dissertation, Heilman4 addressed perceptions of satisfaction with online teaching. One element she researched was faculty/peer relationships. Her participants noted that “networking and sharing with other online faculty members who work in another location” enhanced their satisfaction, but several noted that “lack of interactions or feeling isolated from their peers” diminished their satisfaction with online teaching. In reading their comments, I formed the impression that the interactions were initiated by the individual faculty, rather than facilitated by the institution.

Recently, I have seen blog posts addressing the issue of transforming clinicians to academics. There is a universal understanding that being an expert clinician does not necessarily mean you are a proficient educator. Moreover, transitioning from a face-to-face system to an online environment can be intimidating. Faculty, especially those new to the role, may need additional support.

Having an internal social network for online faculty is a means to achieving a supportive community and building a mentoring culture within an institution. A faculty member who has a sense of connectedness to other faculty (onsite and online) is as important to the successful online environment as is the development of a sense of community for students. The community must serve to enhance learning and teaching for both groups.

There are several published guidelines for successful online teaching—that is, what faculty can do for students. I have taken those principles, modified them, and applied them as suggestions for improving the socialization of faculty. With recognition of those who devised them5,6 and acknowledgement of the poetic license applied, here they are:

• Encourage faculty-to-faculty contact outside mandatory meetings

• Encourage faculty collaboration beyond course/institutional requirements

• Provide for live, interactive events that are fun.

With the ever-increasing number of educational institutions providing online programs (now at about 89%7), it is imperative that we as faculty and program administrators include socialization as a component of faculty orientation and training. What better than a connected faculty to enhance student achievement?

When we’re on site, my faculty colleagues and I plan dinner together. During commencement week, laughter and camaraderie from “unofficial” social activities allow us to relax, celebrate another successful class, and form memories that we carry with us throughout the year. What about your institutions? Please share your ideas about “staying connected” to colleagues in a digital environment by writing to NPEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Keating SB. Curriculum Development and Evaluation in Nursing. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006.

2. Bower BL. Distance education: facing the faculty challenge. Online J Distance Learning Admin. 2001;4(2).

3. Sanderson A, Phua VC, Herda D. The American Faculty Poll. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center; 2000.

4. Heilman JG. Higher education faculty satisfaction with online teaching [dissertation]. 2007. http://hdl.handle.net/2152/3796. Accessed February 15, 2016.

5. Koeckeritz J, Malkiewicz J, Henderson A. The seven principles of good practice: applications for online education in nursing. Nurse Educ. 2002;27(6):283-287.

6. Chickering AW, Gamson ZF. Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin. 1987;39(7):3-7.

7. Parker K, Lenhart A, Moore K. The Digital Revolution and Higher Education: College Presidents, Public Differ on Value of Online Learning. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2011.

Try to Remember …

How often do you misplace your keys or forget why you walked into a room? When I was younger, I dismissed things such as losing my train of thought (my nephew calls that a brain fart), a neglected errand (probably not important enough), or getting lost trying to go somewhere (never was good at directions anyway).

Know that I was never a “list maker.” I gave that up—because I often could not remember where I’d put it. Usually, once I wrote something down, I would eventually (in the same day) recall whatever was on it, so I wouldn’t fret about where I left that list.

Names? I could always tell you where we met, what you were wearing, and where you were sitting. But your name? Forget about it. (Those who have met me know the truth in that statement!)

During particularly stressful or busy times, if I found myself a bit more “absentminded” than usual, I would joke, “Of all the things I’ve lost, I miss my mind the most.”

Now I wonder: Just how serious are those instances of memory lapse? Yes, occasional memory lapses are part of normal aging. Just like our joints, our brains are not as young as they used to be. Even a 90-year-old with a healthy brain has experienced a loss of 10% brain cell volume.1 And let’s be honest, in celebrating major accomplishments (or failures), some of us have killed a few additional brain cells along the way (wink, wink).

We know that as we age, just as our stride has slowed, so too has the sharpness of our recall dulled. However, at what point are those misfires of our brain no longer a minor nuisance?

Data from the Administration on Aging document that in 2013, an estimated 44.7 million US residents were 65 or older.2 An estimated 5 million of them had Alzheimer disease. That translates to one in nine people—scary! This number, researchers predict, will increase to 13.8 million by 2050.3

Moreover, these statistics become more startling as we recognize that the cost of providing long-term and hospice care to people with Alzheimer disease (and other forms of dementia) is estimated to increase from $203 billion in 2013 to $1.2 trillion in 2050 (in 2013 dollars).4 Therefore, it is imperative for us, both as individuals and as health care professionals, to know the warning signs of dementia and be attentive to even seemingly subtle changes in behavior.

Early recognition that these changes are more than minor lapses in memory is important. Delays in diagnosis can result in a reduction of access to available treatments and resources. Yet, at what point do we start to consider those minor instances of forgetfulness not as normal but as indications of developing cognitive problems? My colleagues in gerontology tell us it is when those changes negatively affect activities of daily living and ability to function.

Continue for the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia >>

What is the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia? Would I (or any of my family or friends) recognize it? The diagnosis of dementia is not based on a sole symptom; rather, it requires the existence of at least two types of impairment that are significant and interfere with daily life.

Thankfully, I have adjusted to being “temporarily misplaced” (I don’t call it lost) and smiling at you whilst I try to remember your name. It may seem I jest or am insensitive to a grave health issue—but I am very serious about our need to pay attention to ourselves, to those we care for, and to those we care about (including neighbors). I now live in an area where a “silver alert” (missing elder) is an almost daily occurrence.

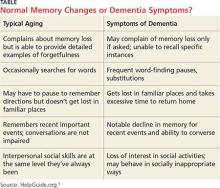

The table provides a comparison of normal-aging memory changes versus dementia symptoms; this is a tool we can use in practice and provide to our patients and their families.5 However, when changes in memory become so pervasive and severe that they are disrupting work, hobbies, social activities, and family relationships, we must recognize that they are the warning signs of Alzheimer disease.6 After reading multiple reports and guides, and witnessing the disease progression in neighbors, I share the three most significant hallmarks of the disease: impaired judgment, difficulty in recalling new information, and unusual behavior.7

It is important to remember—and to communicate to our patients—that memory loss itself does not meet the criteria for dementia. While some may be quick to fear that diagnosis, other factors that can contribute to cognitive problems are stress, depression, vitamin deficiency, thyroid disease, and even dehydration. All of these can be managed, with a resultant reversal of symptoms of memory loss.8 As always, a good health history, review of symptoms, and physical examination will guide us to an accurate diagnosis and plan of care.

There are multiple resources available for patients and families who receive a diagnosis of dementia or Alzheimer disease. Fear of the diagnosis need not blind us to the early warning signs. As NPs and PAs, despite our busy schedules, we must stop and listen to both the patient and the family, and ask the difficult questions about judgment and behavior in our aging patients.

REFERENCES

1. Doty L. Caregiving topics: early signs of dementia. http://alzonline.phhp.ufl.edu/en/reading/EarlySignsFeb08.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

2. CDC. Older persons’ health. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

3. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DL. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778-1783.

4. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):20-245.

5. Wayne M, White M, Smith M. Understanding dementia. www.helpguide.org/articles/alzheimers-dementia/understanding-dementia.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

6. Smith M, Robinson L, Segal R. Age-related memory loss. www.helpguide.org/articles/memory/age-related-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

7. A guide to coping with Alzheimer’s disease: a Harvard Medical School Special Health Report. www.health.harvard.edu/special-health-reports/a-guide-to-coping-with-alzheimers-disease. Accessed December 11, 2015.

8. HelpGuide.org. What’s causing your memory loss? www.helpguide.org/harvard/whats-causing-your-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

How often do you misplace your keys or forget why you walked into a room? When I was younger, I dismissed things such as losing my train of thought (my nephew calls that a brain fart), a neglected errand (probably not important enough), or getting lost trying to go somewhere (never was good at directions anyway).

Know that I was never a “list maker.” I gave that up—because I often could not remember where I’d put it. Usually, once I wrote something down, I would eventually (in the same day) recall whatever was on it, so I wouldn’t fret about where I left that list.

Names? I could always tell you where we met, what you were wearing, and where you were sitting. But your name? Forget about it. (Those who have met me know the truth in that statement!)

During particularly stressful or busy times, if I found myself a bit more “absentminded” than usual, I would joke, “Of all the things I’ve lost, I miss my mind the most.”

Now I wonder: Just how serious are those instances of memory lapse? Yes, occasional memory lapses are part of normal aging. Just like our joints, our brains are not as young as they used to be. Even a 90-year-old with a healthy brain has experienced a loss of 10% brain cell volume.1 And let’s be honest, in celebrating major accomplishments (or failures), some of us have killed a few additional brain cells along the way (wink, wink).