User login

How often do you misplace your keys or forget why you walked into a room? When I was younger, I dismissed things such as losing my train of thought (my nephew calls that a brain fart), a neglected errand (probably not important enough), or getting lost trying to go somewhere (never was good at directions anyway).

Know that I was never a “list maker.” I gave that up—because I often could not remember where I’d put it. Usually, once I wrote something down, I would eventually (in the same day) recall whatever was on it, so I wouldn’t fret about where I left that list.

Names? I could always tell you where we met, what you were wearing, and where you were sitting. But your name? Forget about it. (Those who have met me know the truth in that statement!)

During particularly stressful or busy times, if I found myself a bit more “absentminded” than usual, I would joke, “Of all the things I’ve lost, I miss my mind the most.”

Now I wonder: Just how serious are those instances of memory lapse? Yes, occasional memory lapses are part of normal aging. Just like our joints, our brains are not as young as they used to be. Even a 90-year-old with a healthy brain has experienced a loss of 10% brain cell volume.1 And let’s be honest, in celebrating major accomplishments (or failures), some of us have killed a few additional brain cells along the way (wink, wink).

We know that as we age, just as our stride has slowed, so too has the sharpness of our recall dulled. However, at what point are those misfires of our brain no longer a minor nuisance?

Data from the Administration on Aging document that in 2013, an estimated 44.7 million US residents were 65 or older.2 An estimated 5 million of them had Alzheimer disease. That translates to one in nine people—scary! This number, researchers predict, will increase to 13.8 million by 2050.3

Moreover, these statistics become more startling as we recognize that the cost of providing long-term and hospice care to people with Alzheimer disease (and other forms of dementia) is estimated to increase from $203 billion in 2013 to $1.2 trillion in 2050 (in 2013 dollars).4 Therefore, it is imperative for us, both as individuals and as health care professionals, to know the warning signs of dementia and be attentive to even seemingly subtle changes in behavior.

Early recognition that these changes are more than minor lapses in memory is important. Delays in diagnosis can result in a reduction of access to available treatments and resources. Yet, at what point do we start to consider those minor instances of forgetfulness not as normal but as indications of developing cognitive problems? My colleagues in gerontology tell us it is when those changes negatively affect activities of daily living and ability to function.

Continue for the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia >>

What is the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia? Would I (or any of my family or friends) recognize it? The diagnosis of dementia is not based on a sole symptom; rather, it requires the existence of at least two types of impairment that are significant and interfere with daily life.

Thankfully, I have adjusted to being “temporarily misplaced” (I don’t call it lost) and smiling at you whilst I try to remember your name. It may seem I jest or am insensitive to a grave health issue—but I am very serious about our need to pay attention to ourselves, to those we care for, and to those we care about (including neighbors). I now live in an area where a “silver alert” (missing elder) is an almost daily occurrence.

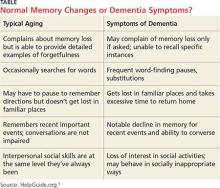

The table provides a comparison of normal-aging memory changes versus dementia symptoms; this is a tool we can use in practice and provide to our patients and their families.5 However, when changes in memory become so pervasive and severe that they are disrupting work, hobbies, social activities, and family relationships, we must recognize that they are the warning signs of Alzheimer disease.6 After reading multiple reports and guides, and witnessing the disease progression in neighbors, I share the three most significant hallmarks of the disease: impaired judgment, difficulty in recalling new information, and unusual behavior.7

It is important to remember—and to communicate to our patients—that memory loss itself does not meet the criteria for dementia. While some may be quick to fear that diagnosis, other factors that can contribute to cognitive problems are stress, depression, vitamin deficiency, thyroid disease, and even dehydration. All of these can be managed, with a resultant reversal of symptoms of memory loss.8 As always, a good health history, review of symptoms, and physical examination will guide us to an accurate diagnosis and plan of care.

There are multiple resources available for patients and families who receive a diagnosis of dementia or Alzheimer disease. Fear of the diagnosis need not blind us to the early warning signs. As NPs and PAs, despite our busy schedules, we must stop and listen to both the patient and the family, and ask the difficult questions about judgment and behavior in our aging patients.

REFERENCES

1. Doty L. Caregiving topics: early signs of dementia. http://alzonline.phhp.ufl.edu/en/reading/EarlySignsFeb08.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

2. CDC. Older persons’ health. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

3. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DL. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778-1783.

4. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):20-245.

5. Wayne M, White M, Smith M. Understanding dementia. www.helpguide.org/articles/alzheimers-dementia/understanding-dementia.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

6. Smith M, Robinson L, Segal R. Age-related memory loss. www.helpguide.org/articles/memory/age-related-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

7. A guide to coping with Alzheimer’s disease: a Harvard Medical School Special Health Report. www.health.harvard.edu/special-health-reports/a-guide-to-coping-with-alzheimers-disease. Accessed December 11, 2015.

8. HelpGuide.org. What’s causing your memory loss? www.helpguide.org/harvard/whats-causing-your-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

How often do you misplace your keys or forget why you walked into a room? When I was younger, I dismissed things such as losing my train of thought (my nephew calls that a brain fart), a neglected errand (probably not important enough), or getting lost trying to go somewhere (never was good at directions anyway).

Know that I was never a “list maker.” I gave that up—because I often could not remember where I’d put it. Usually, once I wrote something down, I would eventually (in the same day) recall whatever was on it, so I wouldn’t fret about where I left that list.

Names? I could always tell you where we met, what you were wearing, and where you were sitting. But your name? Forget about it. (Those who have met me know the truth in that statement!)

During particularly stressful or busy times, if I found myself a bit more “absentminded” than usual, I would joke, “Of all the things I’ve lost, I miss my mind the most.”

Now I wonder: Just how serious are those instances of memory lapse? Yes, occasional memory lapses are part of normal aging. Just like our joints, our brains are not as young as they used to be. Even a 90-year-old with a healthy brain has experienced a loss of 10% brain cell volume.1 And let’s be honest, in celebrating major accomplishments (or failures), some of us have killed a few additional brain cells along the way (wink, wink).

We know that as we age, just as our stride has slowed, so too has the sharpness of our recall dulled. However, at what point are those misfires of our brain no longer a minor nuisance?

Data from the Administration on Aging document that in 2013, an estimated 44.7 million US residents were 65 or older.2 An estimated 5 million of them had Alzheimer disease. That translates to one in nine people—scary! This number, researchers predict, will increase to 13.8 million by 2050.3

Moreover, these statistics become more startling as we recognize that the cost of providing long-term and hospice care to people with Alzheimer disease (and other forms of dementia) is estimated to increase from $203 billion in 2013 to $1.2 trillion in 2050 (in 2013 dollars).4 Therefore, it is imperative for us, both as individuals and as health care professionals, to know the warning signs of dementia and be attentive to even seemingly subtle changes in behavior.

Early recognition that these changes are more than minor lapses in memory is important. Delays in diagnosis can result in a reduction of access to available treatments and resources. Yet, at what point do we start to consider those minor instances of forgetfulness not as normal but as indications of developing cognitive problems? My colleagues in gerontology tell us it is when those changes negatively affect activities of daily living and ability to function.

Continue for the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia >>

What is the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia? Would I (or any of my family or friends) recognize it? The diagnosis of dementia is not based on a sole symptom; rather, it requires the existence of at least two types of impairment that are significant and interfere with daily life.

Thankfully, I have adjusted to being “temporarily misplaced” (I don’t call it lost) and smiling at you whilst I try to remember your name. It may seem I jest or am insensitive to a grave health issue—but I am very serious about our need to pay attention to ourselves, to those we care for, and to those we care about (including neighbors). I now live in an area where a “silver alert” (missing elder) is an almost daily occurrence.

The table provides a comparison of normal-aging memory changes versus dementia symptoms; this is a tool we can use in practice and provide to our patients and their families.5 However, when changes in memory become so pervasive and severe that they are disrupting work, hobbies, social activities, and family relationships, we must recognize that they are the warning signs of Alzheimer disease.6 After reading multiple reports and guides, and witnessing the disease progression in neighbors, I share the three most significant hallmarks of the disease: impaired judgment, difficulty in recalling new information, and unusual behavior.7

It is important to remember—and to communicate to our patients—that memory loss itself does not meet the criteria for dementia. While some may be quick to fear that diagnosis, other factors that can contribute to cognitive problems are stress, depression, vitamin deficiency, thyroid disease, and even dehydration. All of these can be managed, with a resultant reversal of symptoms of memory loss.8 As always, a good health history, review of symptoms, and physical examination will guide us to an accurate diagnosis and plan of care.

There are multiple resources available for patients and families who receive a diagnosis of dementia or Alzheimer disease. Fear of the diagnosis need not blind us to the early warning signs. As NPs and PAs, despite our busy schedules, we must stop and listen to both the patient and the family, and ask the difficult questions about judgment and behavior in our aging patients.

REFERENCES

1. Doty L. Caregiving topics: early signs of dementia. http://alzonline.phhp.ufl.edu/en/reading/EarlySignsFeb08.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

2. CDC. Older persons’ health. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

3. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DL. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778-1783.

4. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):20-245.

5. Wayne M, White M, Smith M. Understanding dementia. www.helpguide.org/articles/alzheimers-dementia/understanding-dementia.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

6. Smith M, Robinson L, Segal R. Age-related memory loss. www.helpguide.org/articles/memory/age-related-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

7. A guide to coping with Alzheimer’s disease: a Harvard Medical School Special Health Report. www.health.harvard.edu/special-health-reports/a-guide-to-coping-with-alzheimers-disease. Accessed December 11, 2015.

8. HelpGuide.org. What’s causing your memory loss? www.helpguide.org/harvard/whats-causing-your-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

How often do you misplace your keys or forget why you walked into a room? When I was younger, I dismissed things such as losing my train of thought (my nephew calls that a brain fart), a neglected errand (probably not important enough), or getting lost trying to go somewhere (never was good at directions anyway).

Know that I was never a “list maker.” I gave that up—because I often could not remember where I’d put it. Usually, once I wrote something down, I would eventually (in the same day) recall whatever was on it, so I wouldn’t fret about where I left that list.

Names? I could always tell you where we met, what you were wearing, and where you were sitting. But your name? Forget about it. (Those who have met me know the truth in that statement!)

During particularly stressful or busy times, if I found myself a bit more “absentminded” than usual, I would joke, “Of all the things I’ve lost, I miss my mind the most.”

Now I wonder: Just how serious are those instances of memory lapse? Yes, occasional memory lapses are part of normal aging. Just like our joints, our brains are not as young as they used to be. Even a 90-year-old with a healthy brain has experienced a loss of 10% brain cell volume.1 And let’s be honest, in celebrating major accomplishments (or failures), some of us have killed a few additional brain cells along the way (wink, wink).

We know that as we age, just as our stride has slowed, so too has the sharpness of our recall dulled. However, at what point are those misfires of our brain no longer a minor nuisance?

Data from the Administration on Aging document that in 2013, an estimated 44.7 million US residents were 65 or older.2 An estimated 5 million of them had Alzheimer disease. That translates to one in nine people—scary! This number, researchers predict, will increase to 13.8 million by 2050.3

Moreover, these statistics become more startling as we recognize that the cost of providing long-term and hospice care to people with Alzheimer disease (and other forms of dementia) is estimated to increase from $203 billion in 2013 to $1.2 trillion in 2050 (in 2013 dollars).4 Therefore, it is imperative for us, both as individuals and as health care professionals, to know the warning signs of dementia and be attentive to even seemingly subtle changes in behavior.

Early recognition that these changes are more than minor lapses in memory is important. Delays in diagnosis can result in a reduction of access to available treatments and resources. Yet, at what point do we start to consider those minor instances of forgetfulness not as normal but as indications of developing cognitive problems? My colleagues in gerontology tell us it is when those changes negatively affect activities of daily living and ability to function.

Continue for the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia >>

What is the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia? Would I (or any of my family or friends) recognize it? The diagnosis of dementia is not based on a sole symptom; rather, it requires the existence of at least two types of impairment that are significant and interfere with daily life.

Thankfully, I have adjusted to being “temporarily misplaced” (I don’t call it lost) and smiling at you whilst I try to remember your name. It may seem I jest or am insensitive to a grave health issue—but I am very serious about our need to pay attention to ourselves, to those we care for, and to those we care about (including neighbors). I now live in an area where a “silver alert” (missing elder) is an almost daily occurrence.

The table provides a comparison of normal-aging memory changes versus dementia symptoms; this is a tool we can use in practice and provide to our patients and their families.5 However, when changes in memory become so pervasive and severe that they are disrupting work, hobbies, social activities, and family relationships, we must recognize that they are the warning signs of Alzheimer disease.6 After reading multiple reports and guides, and witnessing the disease progression in neighbors, I share the three most significant hallmarks of the disease: impaired judgment, difficulty in recalling new information, and unusual behavior.7

It is important to remember—and to communicate to our patients—that memory loss itself does not meet the criteria for dementia. While some may be quick to fear that diagnosis, other factors that can contribute to cognitive problems are stress, depression, vitamin deficiency, thyroid disease, and even dehydration. All of these can be managed, with a resultant reversal of symptoms of memory loss.8 As always, a good health history, review of symptoms, and physical examination will guide us to an accurate diagnosis and plan of care.

There are multiple resources available for patients and families who receive a diagnosis of dementia or Alzheimer disease. Fear of the diagnosis need not blind us to the early warning signs. As NPs and PAs, despite our busy schedules, we must stop and listen to both the patient and the family, and ask the difficult questions about judgment and behavior in our aging patients.

REFERENCES

1. Doty L. Caregiving topics: early signs of dementia. http://alzonline.phhp.ufl.edu/en/reading/EarlySignsFeb08.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

2. CDC. Older persons’ health. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

3. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DL. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778-1783.

4. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):20-245.

5. Wayne M, White M, Smith M. Understanding dementia. www.helpguide.org/articles/alzheimers-dementia/understanding-dementia.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

6. Smith M, Robinson L, Segal R. Age-related memory loss. www.helpguide.org/articles/memory/age-related-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

7. A guide to coping with Alzheimer’s disease: a Harvard Medical School Special Health Report. www.health.harvard.edu/special-health-reports/a-guide-to-coping-with-alzheimers-disease. Accessed December 11, 2015.

8. HelpGuide.org. What’s causing your memory loss? www.helpguide.org/harvard/whats-causing-your-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.