User login

This past August, President Trump, with the advice and consent of the United States Senate, nominated Indiana Health Commissioner Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH, as the nation’s 20th Surgeon General (SG). As the country’s “doctor,” the SG has access to the best available scientific information to advise Americans of ways to improve their health and decrease risk for illness and injury. Overseen by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, the Office of the Surgeon General has no budget or line authority. As a political appointee, the SG ranks three levels below a presidential cabinet member and reports to an assistant health secretary.1

The SG nominally oversees the US Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, an exclusive group of more than 6,700 public health professionals working throughout the federal government with the mission to protect, promote, and advance the health of our nation.2 In 2010, under the Affordable Care Act, the SG was designated as Chair of the National Prevention Council, which coordinates and leads 20 executive departments encouraging prevention, wellness, and health promotion activities.

Past SGs, during their time in office, have quietly gone about their duties, although some have used their platform to raise awareness of specific public health concerns. C. Everett Koop (a Reagan appointee) is among the most-remembered SGs, thanks in part to his use of the media to promote his causes, specifically smoking cessation and AIDS prevention. Newly appointed Dr. Adams, an anesthesiologist by training, is known for his focus on the opioid epidemic, tobacco use, and infant mortality.

As we’ve seen over the years, the limitations of the SG’s role equate to a mixed bag of “results.” For every C. Everett Koop (whether you agree with his views or not, he was prolific!), there are several SGs who came and went from office without making a blip on the public’s radar. Since health care remains at the forefront of our national conversation, the burning question is: If you were a consultant to the SG, which health issues would you prioritize?

I posed this question to 30 of my PA and NP colleagues. While certainly not an official survey—rather, a straw poll—I was nonetheless surprised by the overlap in responses. Here are some of the highlights.

Substance abuse/opioid crisis. Globally, one in every eight deaths result from the use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. According to Humphreys et al, the implications of addiction are clear: It will do massive and increasing damage to humanity if not addressed emergently and at the source.3 But to do so, we must understand the root cause. Neuroscientific research has shown that repeated addictive drug use can rewire the brain’s motivational and reward circuits and influence decision-making.3

This is evidenced by the startling fact that every day, an average of 91 Americans die of opioid overdose.3 In March, the Director-General of the World Health Organization called for more scientifically informed public policies regarding addiction.4 The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis released a preliminary report in August recommending next steps, which included the declaration of a federal state of emergency.5

Mental health. As you may recall from my December 2016 editorial, mental health is a forgotten facet of primary care—and one that is imperative to address.6 Only 43% of family physicians in this country provide mental health care; furthermore, half of Americans with mental health conditions go without essential care, and those with intellectual and developmental disabilities are significantly underserved.6 Perhaps increased efforts to attend to mental health in primary care will subsequently reduce addiction and substance abuse rates, resulting in a physically and mentally healthier America.

Oral health. Dr. Koop was known for his quote, “You can’t be healthy without good oral health.” Unfortunately, the major challenge expressed in Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General—“not all Americans have achieved the same level of oral health and well-being”—is as relevant today as it was when the report was released in 2000.7 We must therefore accelerate efforts toward achieving this goal. We must also address the need for a more diverse and well-distributed oral health workforce.

The CDC Division of Oral Health has made oral health an integral component of public health programs, with a goal of eliminating disparities and improving oral health for all. Continued investment in research, such as that undertaken by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Centers for Research to Reduce Disparities in Oral Health, is critical.8 Lastly, we must continue to expand initiatives to prevent tobacco use and promote better dietary choices.

Obesity. Literature on the health consequences of obesity in both adults and children has increased exponentially in recent decades, due to the condition’s alarming prevalence in the US and other industrialized countries. The CDC reports significant racial and ethnic disparities in obesity, specifically among Hispanics/Latinos compared to non-Hispanic whites. Because obesity significantly contributes to acute and chronic diseases and has a direct relationship to morbidity and mortality, public health officials should target health prevention messages and interventions to those populations with the greatest need.9

Kidney disease. An estimated 31 million people in the US have chronic kidney disease (CKD), and it is the eighth leading cause of death in this country. Shockingly, 9 out of 10 people who have stage 3 CKD are not even aware they have it.10 The cost of CKD in the US is extortionate; research in this area is horrifically underfunded compared to that for other chronic diseases. The entire NIH budget for CKD is $31 billion, while the expense to the patient population is $32 billion—and every five minutes, someone’s kidneys fail.11

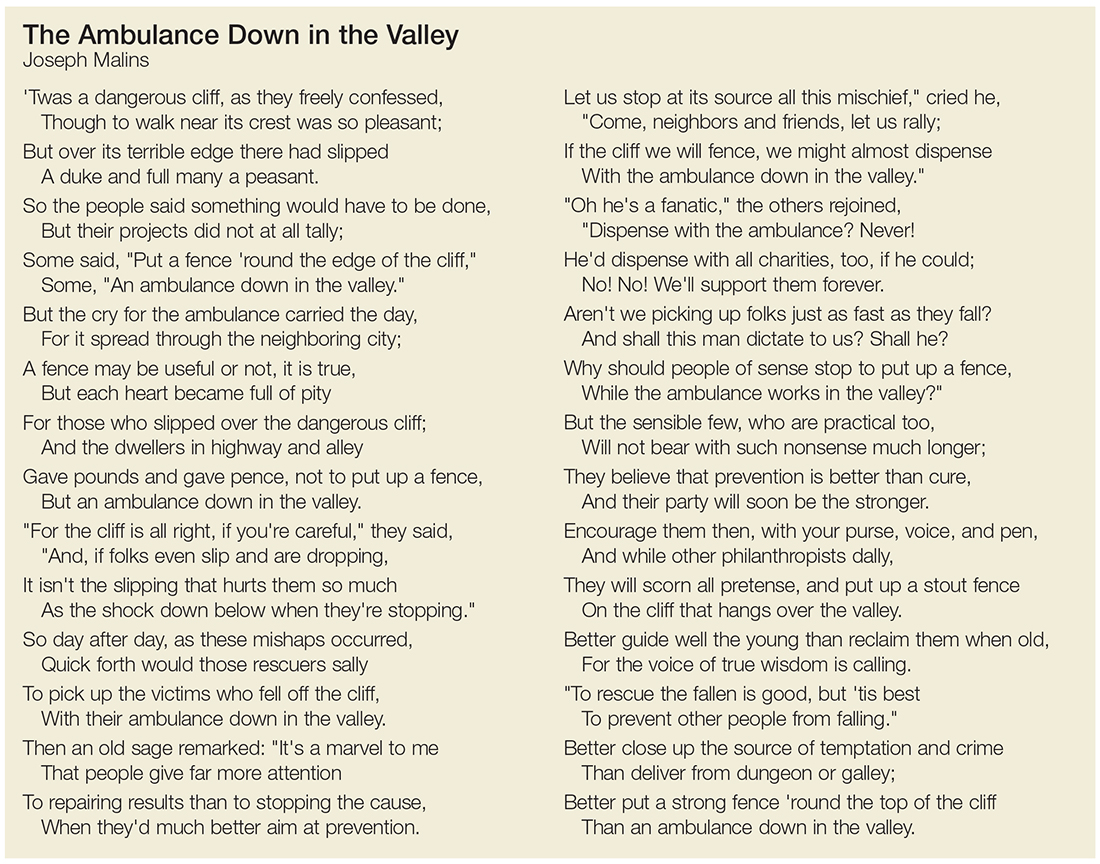

The seemingly obvious question is, what can we do to prevent CKD? As far back as 1948, SG Thomas Parran Jr. advocated for preventive and curative services.12 Alas, I recently came across an excellent poem by Joseph Malins (circa 1855) that speaks volumes about prevention versus cure (see box).

Environmental threats/emerging viruses. Particular attention should be paid to newly identified infectious agents, both locally and internationally, to prevent public health problems—for example, the Zika virus epidemic. In 1896, William Osler said, “Humanity has but three great enemies: infection, famine, and war; of these, by far the greatest, by far the most terrible is infection.”13 We know the factors that contribute to the emergence of new infections: the evolution of pathogenic infectious agents (microbial adaptation and change), development of drug resistance, and vector resistance to pesticides. Other important factors include climate and changing ecosystems, economic development and land use (eg, urbanization, deforestation), and technology and industry (eg, food processing and handling).14

Access to health care. Last but certainly not least, every respondent emphasized that we need to prioritize access to health care and eliminate socioeconomic disparities. But when we recognize that these disparities exist across all populations, we see that this is not an easy task. Lack of health insurance, lack of financial resources, irregular sources of care, legal obstacles, structural barriers, lack of health care providers, language barriers, socioeconomic disparity, and age are all contributing factors that are also obstacles.15 But in order for any of the previously discussed changes in health care to be influential, they must be accessible.

And so I open the floor to you, colleagues: What do you think should be done to improve access to health care? What are your pressing public health issues? Share your thoughts with me at PAeditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

1. Scutti S. Dr. Jerome Adams confirmed as Surgeon General. www.cnn.com/2017/08/04/health/jerome-adams-surgeon-general-confirmation/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. About the Office of the Surgeon General. www.surgeongeneral.gov/about/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2017.

3. Humphreys K, Malenka RC, Knutson B, MacCoun RJ. Brains, environments, and policy responses to addiction. Science. 2017;356(6344):1237-1238.

4. Chan M. Opening remarks at the 60th session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs. www.who.int/dg/speeches/2017/commission-narcotic-drugs/en/. Accessed September 1, 2017.

5. Burns J. Opioid Task Force recommends state of emergency and (sort of) bold treatment agenda. www.forbes.com/sites/janetwburns/2017/08/02/opioid-task-force-recommends-state-of-emergency-and-sort-of-bold-treatment-agenda/#378810163956. Accessed September 1, 2017.

6. Danielsen RD. Mental health: a forgotten facet of primary care. Clinician Reviews. 2016;26(12):7,46.

7. NIH National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Oral health in America: report of the Surgeon General (executive summary). Rockville, MD: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; 2000. Page 287.

8. Satcher D, Nottingham JH. Revisiting oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. AJPH. 2017;107(suppl 1):S32-S33.

9. Hu F. Obesity Epidemiology. 2008; New York: Oxford University Press. 5-7.

10. American Kidney Fund. 2015 kidney disease statistics. www.kidneyfund.org/assets/pdf/kidney-disease-statistics.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2017.

11. Tyler. Statistics on chronic kidney disease (CKD) that may shock you. www.dietitiansathome.com/post/statistics-on-chronic-kidney-disease-ckd.

12. Sledge D. Linking public health and individual medicine: the health policy approach of Surgeon General Thomas Parran. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(4):509-516.

13. Osler W. The study of the fevers of the south. JAMA. 1896;XXVI(21):999-1004.

14. Fauci AS, Touchette NA, Folkers GK. Emerging infectious diseases: a 10-year perspective from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11(4):519-525.

15. Mandal A. Disparities in access to health care. www.news-medical.net/health/Disparities-in-Access-to-Health-Care.aspx. Accessed September 1, 2017.

This past August, President Trump, with the advice and consent of the United States Senate, nominated Indiana Health Commissioner Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH, as the nation’s 20th Surgeon General (SG). As the country’s “doctor,” the SG has access to the best available scientific information to advise Americans of ways to improve their health and decrease risk for illness and injury. Overseen by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, the Office of the Surgeon General has no budget or line authority. As a political appointee, the SG ranks three levels below a presidential cabinet member and reports to an assistant health secretary.1

The SG nominally oversees the US Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, an exclusive group of more than 6,700 public health professionals working throughout the federal government with the mission to protect, promote, and advance the health of our nation.2 In 2010, under the Affordable Care Act, the SG was designated as Chair of the National Prevention Council, which coordinates and leads 20 executive departments encouraging prevention, wellness, and health promotion activities.

Past SGs, during their time in office, have quietly gone about their duties, although some have used their platform to raise awareness of specific public health concerns. C. Everett Koop (a Reagan appointee) is among the most-remembered SGs, thanks in part to his use of the media to promote his causes, specifically smoking cessation and AIDS prevention. Newly appointed Dr. Adams, an anesthesiologist by training, is known for his focus on the opioid epidemic, tobacco use, and infant mortality.

As we’ve seen over the years, the limitations of the SG’s role equate to a mixed bag of “results.” For every C. Everett Koop (whether you agree with his views or not, he was prolific!), there are several SGs who came and went from office without making a blip on the public’s radar. Since health care remains at the forefront of our national conversation, the burning question is: If you were a consultant to the SG, which health issues would you prioritize?

I posed this question to 30 of my PA and NP colleagues. While certainly not an official survey—rather, a straw poll—I was nonetheless surprised by the overlap in responses. Here are some of the highlights.

Substance abuse/opioid crisis. Globally, one in every eight deaths result from the use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. According to Humphreys et al, the implications of addiction are clear: It will do massive and increasing damage to humanity if not addressed emergently and at the source.3 But to do so, we must understand the root cause. Neuroscientific research has shown that repeated addictive drug use can rewire the brain’s motivational and reward circuits and influence decision-making.3

This is evidenced by the startling fact that every day, an average of 91 Americans die of opioid overdose.3 In March, the Director-General of the World Health Organization called for more scientifically informed public policies regarding addiction.4 The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis released a preliminary report in August recommending next steps, which included the declaration of a federal state of emergency.5

Mental health. As you may recall from my December 2016 editorial, mental health is a forgotten facet of primary care—and one that is imperative to address.6 Only 43% of family physicians in this country provide mental health care; furthermore, half of Americans with mental health conditions go without essential care, and those with intellectual and developmental disabilities are significantly underserved.6 Perhaps increased efforts to attend to mental health in primary care will subsequently reduce addiction and substance abuse rates, resulting in a physically and mentally healthier America.

Oral health. Dr. Koop was known for his quote, “You can’t be healthy without good oral health.” Unfortunately, the major challenge expressed in Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General—“not all Americans have achieved the same level of oral health and well-being”—is as relevant today as it was when the report was released in 2000.7 We must therefore accelerate efforts toward achieving this goal. We must also address the need for a more diverse and well-distributed oral health workforce.

The CDC Division of Oral Health has made oral health an integral component of public health programs, with a goal of eliminating disparities and improving oral health for all. Continued investment in research, such as that undertaken by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Centers for Research to Reduce Disparities in Oral Health, is critical.8 Lastly, we must continue to expand initiatives to prevent tobacco use and promote better dietary choices.

Obesity. Literature on the health consequences of obesity in both adults and children has increased exponentially in recent decades, due to the condition’s alarming prevalence in the US and other industrialized countries. The CDC reports significant racial and ethnic disparities in obesity, specifically among Hispanics/Latinos compared to non-Hispanic whites. Because obesity significantly contributes to acute and chronic diseases and has a direct relationship to morbidity and mortality, public health officials should target health prevention messages and interventions to those populations with the greatest need.9

Kidney disease. An estimated 31 million people in the US have chronic kidney disease (CKD), and it is the eighth leading cause of death in this country. Shockingly, 9 out of 10 people who have stage 3 CKD are not even aware they have it.10 The cost of CKD in the US is extortionate; research in this area is horrifically underfunded compared to that for other chronic diseases. The entire NIH budget for CKD is $31 billion, while the expense to the patient population is $32 billion—and every five minutes, someone’s kidneys fail.11

The seemingly obvious question is, what can we do to prevent CKD? As far back as 1948, SG Thomas Parran Jr. advocated for preventive and curative services.12 Alas, I recently came across an excellent poem by Joseph Malins (circa 1855) that speaks volumes about prevention versus cure (see box).

Environmental threats/emerging viruses. Particular attention should be paid to newly identified infectious agents, both locally and internationally, to prevent public health problems—for example, the Zika virus epidemic. In 1896, William Osler said, “Humanity has but three great enemies: infection, famine, and war; of these, by far the greatest, by far the most terrible is infection.”13 We know the factors that contribute to the emergence of new infections: the evolution of pathogenic infectious agents (microbial adaptation and change), development of drug resistance, and vector resistance to pesticides. Other important factors include climate and changing ecosystems, economic development and land use (eg, urbanization, deforestation), and technology and industry (eg, food processing and handling).14

Access to health care. Last but certainly not least, every respondent emphasized that we need to prioritize access to health care and eliminate socioeconomic disparities. But when we recognize that these disparities exist across all populations, we see that this is not an easy task. Lack of health insurance, lack of financial resources, irregular sources of care, legal obstacles, structural barriers, lack of health care providers, language barriers, socioeconomic disparity, and age are all contributing factors that are also obstacles.15 But in order for any of the previously discussed changes in health care to be influential, they must be accessible.

And so I open the floor to you, colleagues: What do you think should be done to improve access to health care? What are your pressing public health issues? Share your thoughts with me at PAeditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

This past August, President Trump, with the advice and consent of the United States Senate, nominated Indiana Health Commissioner Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH, as the nation’s 20th Surgeon General (SG). As the country’s “doctor,” the SG has access to the best available scientific information to advise Americans of ways to improve their health and decrease risk for illness and injury. Overseen by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, the Office of the Surgeon General has no budget or line authority. As a political appointee, the SG ranks three levels below a presidential cabinet member and reports to an assistant health secretary.1

The SG nominally oversees the US Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, an exclusive group of more than 6,700 public health professionals working throughout the federal government with the mission to protect, promote, and advance the health of our nation.2 In 2010, under the Affordable Care Act, the SG was designated as Chair of the National Prevention Council, which coordinates and leads 20 executive departments encouraging prevention, wellness, and health promotion activities.

Past SGs, during their time in office, have quietly gone about their duties, although some have used their platform to raise awareness of specific public health concerns. C. Everett Koop (a Reagan appointee) is among the most-remembered SGs, thanks in part to his use of the media to promote his causes, specifically smoking cessation and AIDS prevention. Newly appointed Dr. Adams, an anesthesiologist by training, is known for his focus on the opioid epidemic, tobacco use, and infant mortality.

As we’ve seen over the years, the limitations of the SG’s role equate to a mixed bag of “results.” For every C. Everett Koop (whether you agree with his views or not, he was prolific!), there are several SGs who came and went from office without making a blip on the public’s radar. Since health care remains at the forefront of our national conversation, the burning question is: If you were a consultant to the SG, which health issues would you prioritize?

I posed this question to 30 of my PA and NP colleagues. While certainly not an official survey—rather, a straw poll—I was nonetheless surprised by the overlap in responses. Here are some of the highlights.

Substance abuse/opioid crisis. Globally, one in every eight deaths result from the use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. According to Humphreys et al, the implications of addiction are clear: It will do massive and increasing damage to humanity if not addressed emergently and at the source.3 But to do so, we must understand the root cause. Neuroscientific research has shown that repeated addictive drug use can rewire the brain’s motivational and reward circuits and influence decision-making.3

This is evidenced by the startling fact that every day, an average of 91 Americans die of opioid overdose.3 In March, the Director-General of the World Health Organization called for more scientifically informed public policies regarding addiction.4 The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis released a preliminary report in August recommending next steps, which included the declaration of a federal state of emergency.5

Mental health. As you may recall from my December 2016 editorial, mental health is a forgotten facet of primary care—and one that is imperative to address.6 Only 43% of family physicians in this country provide mental health care; furthermore, half of Americans with mental health conditions go without essential care, and those with intellectual and developmental disabilities are significantly underserved.6 Perhaps increased efforts to attend to mental health in primary care will subsequently reduce addiction and substance abuse rates, resulting in a physically and mentally healthier America.

Oral health. Dr. Koop was known for his quote, “You can’t be healthy without good oral health.” Unfortunately, the major challenge expressed in Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General—“not all Americans have achieved the same level of oral health and well-being”—is as relevant today as it was when the report was released in 2000.7 We must therefore accelerate efforts toward achieving this goal. We must also address the need for a more diverse and well-distributed oral health workforce.

The CDC Division of Oral Health has made oral health an integral component of public health programs, with a goal of eliminating disparities and improving oral health for all. Continued investment in research, such as that undertaken by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Centers for Research to Reduce Disparities in Oral Health, is critical.8 Lastly, we must continue to expand initiatives to prevent tobacco use and promote better dietary choices.

Obesity. Literature on the health consequences of obesity in both adults and children has increased exponentially in recent decades, due to the condition’s alarming prevalence in the US and other industrialized countries. The CDC reports significant racial and ethnic disparities in obesity, specifically among Hispanics/Latinos compared to non-Hispanic whites. Because obesity significantly contributes to acute and chronic diseases and has a direct relationship to morbidity and mortality, public health officials should target health prevention messages and interventions to those populations with the greatest need.9

Kidney disease. An estimated 31 million people in the US have chronic kidney disease (CKD), and it is the eighth leading cause of death in this country. Shockingly, 9 out of 10 people who have stage 3 CKD are not even aware they have it.10 The cost of CKD in the US is extortionate; research in this area is horrifically underfunded compared to that for other chronic diseases. The entire NIH budget for CKD is $31 billion, while the expense to the patient population is $32 billion—and every five minutes, someone’s kidneys fail.11

The seemingly obvious question is, what can we do to prevent CKD? As far back as 1948, SG Thomas Parran Jr. advocated for preventive and curative services.12 Alas, I recently came across an excellent poem by Joseph Malins (circa 1855) that speaks volumes about prevention versus cure (see box).

Environmental threats/emerging viruses. Particular attention should be paid to newly identified infectious agents, both locally and internationally, to prevent public health problems—for example, the Zika virus epidemic. In 1896, William Osler said, “Humanity has but three great enemies: infection, famine, and war; of these, by far the greatest, by far the most terrible is infection.”13 We know the factors that contribute to the emergence of new infections: the evolution of pathogenic infectious agents (microbial adaptation and change), development of drug resistance, and vector resistance to pesticides. Other important factors include climate and changing ecosystems, economic development and land use (eg, urbanization, deforestation), and technology and industry (eg, food processing and handling).14

Access to health care. Last but certainly not least, every respondent emphasized that we need to prioritize access to health care and eliminate socioeconomic disparities. But when we recognize that these disparities exist across all populations, we see that this is not an easy task. Lack of health insurance, lack of financial resources, irregular sources of care, legal obstacles, structural barriers, lack of health care providers, language barriers, socioeconomic disparity, and age are all contributing factors that are also obstacles.15 But in order for any of the previously discussed changes in health care to be influential, they must be accessible.

And so I open the floor to you, colleagues: What do you think should be done to improve access to health care? What are your pressing public health issues? Share your thoughts with me at PAeditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

1. Scutti S. Dr. Jerome Adams confirmed as Surgeon General. www.cnn.com/2017/08/04/health/jerome-adams-surgeon-general-confirmation/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. About the Office of the Surgeon General. www.surgeongeneral.gov/about/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2017.

3. Humphreys K, Malenka RC, Knutson B, MacCoun RJ. Brains, environments, and policy responses to addiction. Science. 2017;356(6344):1237-1238.

4. Chan M. Opening remarks at the 60th session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs. www.who.int/dg/speeches/2017/commission-narcotic-drugs/en/. Accessed September 1, 2017.

5. Burns J. Opioid Task Force recommends state of emergency and (sort of) bold treatment agenda. www.forbes.com/sites/janetwburns/2017/08/02/opioid-task-force-recommends-state-of-emergency-and-sort-of-bold-treatment-agenda/#378810163956. Accessed September 1, 2017.

6. Danielsen RD. Mental health: a forgotten facet of primary care. Clinician Reviews. 2016;26(12):7,46.

7. NIH National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Oral health in America: report of the Surgeon General (executive summary). Rockville, MD: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; 2000. Page 287.

8. Satcher D, Nottingham JH. Revisiting oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. AJPH. 2017;107(suppl 1):S32-S33.

9. Hu F. Obesity Epidemiology. 2008; New York: Oxford University Press. 5-7.

10. American Kidney Fund. 2015 kidney disease statistics. www.kidneyfund.org/assets/pdf/kidney-disease-statistics.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2017.

11. Tyler. Statistics on chronic kidney disease (CKD) that may shock you. www.dietitiansathome.com/post/statistics-on-chronic-kidney-disease-ckd.

12. Sledge D. Linking public health and individual medicine: the health policy approach of Surgeon General Thomas Parran. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(4):509-516.

13. Osler W. The study of the fevers of the south. JAMA. 1896;XXVI(21):999-1004.

14. Fauci AS, Touchette NA, Folkers GK. Emerging infectious diseases: a 10-year perspective from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11(4):519-525.

15. Mandal A. Disparities in access to health care. www.news-medical.net/health/Disparities-in-Access-to-Health-Care.aspx. Accessed September 1, 2017.

1. Scutti S. Dr. Jerome Adams confirmed as Surgeon General. www.cnn.com/2017/08/04/health/jerome-adams-surgeon-general-confirmation/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. About the Office of the Surgeon General. www.surgeongeneral.gov/about/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2017.

3. Humphreys K, Malenka RC, Knutson B, MacCoun RJ. Brains, environments, and policy responses to addiction. Science. 2017;356(6344):1237-1238.

4. Chan M. Opening remarks at the 60th session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs. www.who.int/dg/speeches/2017/commission-narcotic-drugs/en/. Accessed September 1, 2017.

5. Burns J. Opioid Task Force recommends state of emergency and (sort of) bold treatment agenda. www.forbes.com/sites/janetwburns/2017/08/02/opioid-task-force-recommends-state-of-emergency-and-sort-of-bold-treatment-agenda/#378810163956. Accessed September 1, 2017.

6. Danielsen RD. Mental health: a forgotten facet of primary care. Clinician Reviews. 2016;26(12):7,46.

7. NIH National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Oral health in America: report of the Surgeon General (executive summary). Rockville, MD: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; 2000. Page 287.

8. Satcher D, Nottingham JH. Revisiting oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. AJPH. 2017;107(suppl 1):S32-S33.

9. Hu F. Obesity Epidemiology. 2008; New York: Oxford University Press. 5-7.

10. American Kidney Fund. 2015 kidney disease statistics. www.kidneyfund.org/assets/pdf/kidney-disease-statistics.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2017.

11. Tyler. Statistics on chronic kidney disease (CKD) that may shock you. www.dietitiansathome.com/post/statistics-on-chronic-kidney-disease-ckd.

12. Sledge D. Linking public health and individual medicine: the health policy approach of Surgeon General Thomas Parran. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(4):509-516.

13. Osler W. The study of the fevers of the south. JAMA. 1896;XXVI(21):999-1004.

14. Fauci AS, Touchette NA, Folkers GK. Emerging infectious diseases: a 10-year perspective from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11(4):519-525.

15. Mandal A. Disparities in access to health care. www.news-medical.net/health/Disparities-in-Access-to-Health-Care.aspx. Accessed September 1, 2017.