User login

Part 4: Talking to Older Patients About Sex and STIs

Having established that there is a documented increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among older Americans, and furthermore recognizing that a contributing factor to this trend may be communication gaps between patients and their health care providers, I now want to address the “What do we do about it?” aspect of our discussion. As clinicians, we know that the core focus around infectious diseases of any kind is prevention.

There are 3 types of prevention, as noted by Fos and Fine in Introduction to Public Health, all of which fit into our current topic: primary (eliminating risk factors), secondary (early detection), and tertiary (eliminating or moderating disability associated with advanced disease).1 The following recommendations fall into at least one of these categories.

1. All clinicians need to be involved in educating older Americans about the risks for STIs. Providers should routinely ask seniors if they are sexually active and should be prepared to recommend appropriate screening and education resources. Essentially, older adults should be getting the same basic “safe sex” education that younger people receive: learning about STIs, from recognizing the signs to understanding how STIs complicate other chronic medical conditions.2,3

2. Seniors also need education on the importance—and proper use—of condoms. Furthermore, we should go a step further and ensure that free condoms are distributed in places where seniors live and congregate. People older than 60 report the lowest condom use of any population.2,3

3. Information on STI detection and treatment options needs to be well publicized. For example, Medicare provides free STI screenings and low-cost treatments. We need to make sure our older patients are aware of this benefit and encourage them to make use of it.

4. Older Americans should be screened for STIs, regardless of age, per CDC guidelines. Seniors should get annual testing if they have new sexual partners—which means they must be asked the difficult questions.

And that’s the crux of the issue: Family members and clinicians may find it uncomfortable to have this conversation with Grandpa or Grandma. But there should be a dialogue to ensure they are aware of their risk for STIs, as well as how to prevent them.3 A well-known NP colleague reminded me of the importance of emphasizing to our older patients that anything discussed within the encounter is confidential and will not be disclosed without their permission. She starts off her conversations with patients by saying, “A lot of people your age experience …” or “Please don’t be insulted if I ask you about …” or “Is it OK if I ask you a few very personal questions?”

Continue to: It is critical...

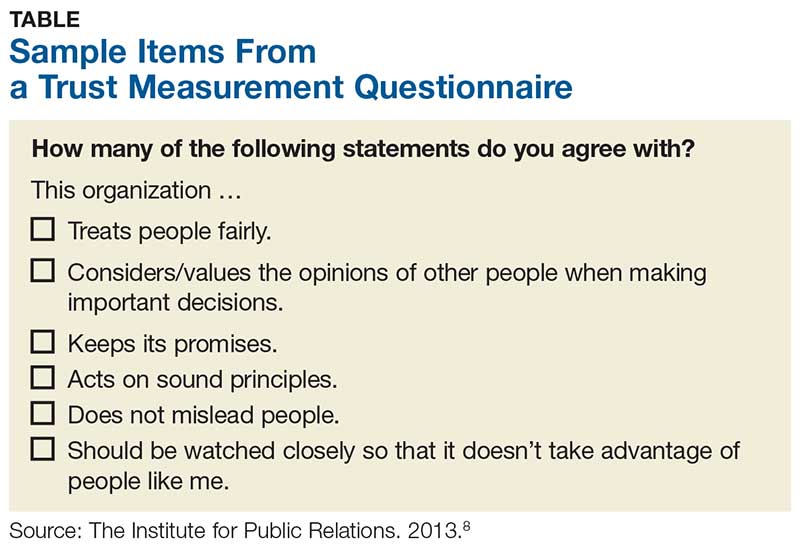

It is critical to keep an open mind and accepting attitude when discussing sexuality or intimate issues with older patients. Paying attention to patients’ verbal and nonverbal cues is also essential. Clinicians should never assume older adults are sexually inactive, no longer care about sex, or are necessarily heterosexual. There was an excellent article in the Journal of Family Practice a few years ago on “How to discuss sex with elderly patients” that is worth rereading. In it, the authors suggest using the PLISSIT model to facilitate a conversation with your elderly patient. As explained in the article, the acronym “is a reminder to seek Permission to discuss sexuality, share Limited information about sexual issues that affect the older adult, provide Specific Suggestions to improve sexual health, and offer to provide a referral for Intensive Therapy if needed.”4 The Table offers some examples of how to address each step of PLISSIT.

So, as we wrap up our examination of this issue, I encourage you to open this dialogue with your older patients. In light of the increasing number of older patients with STIs, it is essential for clinicians to obtain an accurate and complete sexual history for patients of any age. That starts with asking the appropriate questions, preferably in a manner that puts the patient at ease to share important details. If you have additional ideas about what we can do to reverse this STI trend, please share them with me at PAeditor@MDedge.com.

1. Goldstein RL, Goldstein K, Dwelle TL. Introduction to Public Health. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 2015.

2. Cohen JK. STDs on the rise among senior. Becker's Hospital Review. May 18, 2018. www.beckershospitalreview.com/population-health/stds-on-the-rise-among-seniors.html. Accessed May 22, 2019.

3. Humphrey D. Seniors at high risk for sexually transmitted diseases [STDs]. HomeHelpers. March 31, 2018. https://www.homehelpershomecare.com/clearwater/blog/2018/13/seniors-at-high-risk-for-sexually-transmitted-diseases-stds. Accessed Mary 22, 2019.

4. Omole F, Fresh EM, Sow C, et al. How to discuss sex with elderly patients. J Fam Pract. 2014;63(4):E1-E4.

Having established that there is a documented increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among older Americans, and furthermore recognizing that a contributing factor to this trend may be communication gaps between patients and their health care providers, I now want to address the “What do we do about it?” aspect of our discussion. As clinicians, we know that the core focus around infectious diseases of any kind is prevention.

There are 3 types of prevention, as noted by Fos and Fine in Introduction to Public Health, all of which fit into our current topic: primary (eliminating risk factors), secondary (early detection), and tertiary (eliminating or moderating disability associated with advanced disease).1 The following recommendations fall into at least one of these categories.

1. All clinicians need to be involved in educating older Americans about the risks for STIs. Providers should routinely ask seniors if they are sexually active and should be prepared to recommend appropriate screening and education resources. Essentially, older adults should be getting the same basic “safe sex” education that younger people receive: learning about STIs, from recognizing the signs to understanding how STIs complicate other chronic medical conditions.2,3

2. Seniors also need education on the importance—and proper use—of condoms. Furthermore, we should go a step further and ensure that free condoms are distributed in places where seniors live and congregate. People older than 60 report the lowest condom use of any population.2,3

3. Information on STI detection and treatment options needs to be well publicized. For example, Medicare provides free STI screenings and low-cost treatments. We need to make sure our older patients are aware of this benefit and encourage them to make use of it.

4. Older Americans should be screened for STIs, regardless of age, per CDC guidelines. Seniors should get annual testing if they have new sexual partners—which means they must be asked the difficult questions.

And that’s the crux of the issue: Family members and clinicians may find it uncomfortable to have this conversation with Grandpa or Grandma. But there should be a dialogue to ensure they are aware of their risk for STIs, as well as how to prevent them.3 A well-known NP colleague reminded me of the importance of emphasizing to our older patients that anything discussed within the encounter is confidential and will not be disclosed without their permission. She starts off her conversations with patients by saying, “A lot of people your age experience …” or “Please don’t be insulted if I ask you about …” or “Is it OK if I ask you a few very personal questions?”

Continue to: It is critical...

It is critical to keep an open mind and accepting attitude when discussing sexuality or intimate issues with older patients. Paying attention to patients’ verbal and nonverbal cues is also essential. Clinicians should never assume older adults are sexually inactive, no longer care about sex, or are necessarily heterosexual. There was an excellent article in the Journal of Family Practice a few years ago on “How to discuss sex with elderly patients” that is worth rereading. In it, the authors suggest using the PLISSIT model to facilitate a conversation with your elderly patient. As explained in the article, the acronym “is a reminder to seek Permission to discuss sexuality, share Limited information about sexual issues that affect the older adult, provide Specific Suggestions to improve sexual health, and offer to provide a referral for Intensive Therapy if needed.”4 The Table offers some examples of how to address each step of PLISSIT.

So, as we wrap up our examination of this issue, I encourage you to open this dialogue with your older patients. In light of the increasing number of older patients with STIs, it is essential for clinicians to obtain an accurate and complete sexual history for patients of any age. That starts with asking the appropriate questions, preferably in a manner that puts the patient at ease to share important details. If you have additional ideas about what we can do to reverse this STI trend, please share them with me at PAeditor@MDedge.com.

Having established that there is a documented increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among older Americans, and furthermore recognizing that a contributing factor to this trend may be communication gaps between patients and their health care providers, I now want to address the “What do we do about it?” aspect of our discussion. As clinicians, we know that the core focus around infectious diseases of any kind is prevention.

There are 3 types of prevention, as noted by Fos and Fine in Introduction to Public Health, all of which fit into our current topic: primary (eliminating risk factors), secondary (early detection), and tertiary (eliminating or moderating disability associated with advanced disease).1 The following recommendations fall into at least one of these categories.

1. All clinicians need to be involved in educating older Americans about the risks for STIs. Providers should routinely ask seniors if they are sexually active and should be prepared to recommend appropriate screening and education resources. Essentially, older adults should be getting the same basic “safe sex” education that younger people receive: learning about STIs, from recognizing the signs to understanding how STIs complicate other chronic medical conditions.2,3

2. Seniors also need education on the importance—and proper use—of condoms. Furthermore, we should go a step further and ensure that free condoms are distributed in places where seniors live and congregate. People older than 60 report the lowest condom use of any population.2,3

3. Information on STI detection and treatment options needs to be well publicized. For example, Medicare provides free STI screenings and low-cost treatments. We need to make sure our older patients are aware of this benefit and encourage them to make use of it.

4. Older Americans should be screened for STIs, regardless of age, per CDC guidelines. Seniors should get annual testing if they have new sexual partners—which means they must be asked the difficult questions.

And that’s the crux of the issue: Family members and clinicians may find it uncomfortable to have this conversation with Grandpa or Grandma. But there should be a dialogue to ensure they are aware of their risk for STIs, as well as how to prevent them.3 A well-known NP colleague reminded me of the importance of emphasizing to our older patients that anything discussed within the encounter is confidential and will not be disclosed without their permission. She starts off her conversations with patients by saying, “A lot of people your age experience …” or “Please don’t be insulted if I ask you about …” or “Is it OK if I ask you a few very personal questions?”

Continue to: It is critical...

It is critical to keep an open mind and accepting attitude when discussing sexuality or intimate issues with older patients. Paying attention to patients’ verbal and nonverbal cues is also essential. Clinicians should never assume older adults are sexually inactive, no longer care about sex, or are necessarily heterosexual. There was an excellent article in the Journal of Family Practice a few years ago on “How to discuss sex with elderly patients” that is worth rereading. In it, the authors suggest using the PLISSIT model to facilitate a conversation with your elderly patient. As explained in the article, the acronym “is a reminder to seek Permission to discuss sexuality, share Limited information about sexual issues that affect the older adult, provide Specific Suggestions to improve sexual health, and offer to provide a referral for Intensive Therapy if needed.”4 The Table offers some examples of how to address each step of PLISSIT.

So, as we wrap up our examination of this issue, I encourage you to open this dialogue with your older patients. In light of the increasing number of older patients with STIs, it is essential for clinicians to obtain an accurate and complete sexual history for patients of any age. That starts with asking the appropriate questions, preferably in a manner that puts the patient at ease to share important details. If you have additional ideas about what we can do to reverse this STI trend, please share them with me at PAeditor@MDedge.com.

1. Goldstein RL, Goldstein K, Dwelle TL. Introduction to Public Health. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 2015.

2. Cohen JK. STDs on the rise among senior. Becker's Hospital Review. May 18, 2018. www.beckershospitalreview.com/population-health/stds-on-the-rise-among-seniors.html. Accessed May 22, 2019.

3. Humphrey D. Seniors at high risk for sexually transmitted diseases [STDs]. HomeHelpers. March 31, 2018. https://www.homehelpershomecare.com/clearwater/blog/2018/13/seniors-at-high-risk-for-sexually-transmitted-diseases-stds. Accessed Mary 22, 2019.

4. Omole F, Fresh EM, Sow C, et al. How to discuss sex with elderly patients. J Fam Pract. 2014;63(4):E1-E4.

1. Goldstein RL, Goldstein K, Dwelle TL. Introduction to Public Health. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 2015.

2. Cohen JK. STDs on the rise among senior. Becker's Hospital Review. May 18, 2018. www.beckershospitalreview.com/population-health/stds-on-the-rise-among-seniors.html. Accessed May 22, 2019.

3. Humphrey D. Seniors at high risk for sexually transmitted diseases [STDs]. HomeHelpers. March 31, 2018. https://www.homehelpershomecare.com/clearwater/blog/2018/13/seniors-at-high-risk-for-sexually-transmitted-diseases-stds. Accessed Mary 22, 2019.

4. Omole F, Fresh EM, Sow C, et al. How to discuss sex with elderly patients. J Fam Pract. 2014;63(4):E1-E4.

Part 3: Talkin’ ’bout My Generation

Members of the baby boom generation (yes, my generation)—the nomenclature given to the 76 million people born between 1946 and 1964—are now in our 50s, 60s, and 70s. Many of us are enjoying our retirement while others are still working. Regardless of our circumstances, we all share one challenge: aging as comfortably as we can. It’s a fact of our lives that as we age, we battle risk factors for a variety of conditions, ranging from diabetes, heart disease, and Alzheimer disease to … sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Ever since I saw the statistics about increasing rates of STIs among older Americans, I’ve been mulling possible explanations for this trend. In conversation with my CR colleagues, the question arose as to whether the fact that the current population of senior citizens is comprised largely of Baby Boomers has had an impact. It’s certainly worth considering!

We (the Baby Boomers) are more savvy, assertive, health-conscious, and engaged in our health care than the generations that preceded us.1,2 When I look around at my friends and colleagues, I see a group of people who want to live more active lives and remain socially engaged—even as we manage our chronic conditions! As self-determining patients, we are likely to question established principles of medical care, demanding greater attention to our own definitions of health-related quality of life, including a satisfactory sex life.3

In fact, some of this increase in STIs among older Americans could be explained by the availability of treatments that address the sexual dysfunction that comes with aging. Previous generations of older adults have faced menopause and erectile dysfunction—but Baby Boomers are living and aging at a time when the symptoms can be more effectively managed. For older women, there are bioidentical hormones to replace those lost during menopause, which is often cited as the primary offender affecting their sexual lives (despite research suggesting that social and psychologic factors—emotional well-being, a strong emotional association with one’s partner, and positive body image—may be more foretelling of sexual activity later in life than the hormonal changes related to menopause).4

As for erectile dysfunction, yes, some men still feel awkward about bringing it up with their clinician; it can feel enfeebling for men to acknowledge, even though the physiologic changes are explained by the biology of aging (as we alluded to last week). Continuing sales of Viagra and Cialis suggest that boomer men are overcoming the stigmas of revealing their erectile dysfunction, however.

And maybe that is a contributing factor to this trend in STIs: We are being equipped for sexual performance, but perhaps we haven’t been adequately educated on what the consequences of our sexual encounters are. A lot of today’s seniors were already married when sex education gained prominence and perhaps missed the “safe sex” talks.

When I discussed this with a colleague of mine—a retired employee of the State Department—he noted that this topic was talked about even among US Embassy staff! At the risk of making a sweeping generalization and stating the obvious, he observed that “sexual mores have changed over time. Even many generations ago, they thought previous generations had been restrictive about sexual behavior!” Nevertheless, we agreed that the generation now emerging as “older Americans” grew up during the ’60s Free Love movement—and that philosophy seems to have carried into some individuals’ current sexual behavior. My colleague also noted that “as we get older, we lose partners—and sexual monogamy is lost with the loss of a partner.”

Continue to: The Baby Boomers...

The Baby Boomers are by far the most sexually liberal generation of older adults that this country has ever seen. Providing health care to this population requires addressing all health care needs, including sexual health and prevention. Next week, we’ll examine ways clinicians can comfortably broach these topics with older patients.

In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts: Is this the Second Spring of the Summer of Love generation? Whether you’re a Boomer or a Millennial or anyone in between, feel free to write to me at PAeditor@mdedge.com.

1. Kickbusch I, Payne L. Twenty-first century health promotion: the public health revolution meets the wellness revolution. Health Promot Int. 2003;18(4):275-278.

2. Wilson LB, Simson SP (eds). Civic Engagement and the Baby Boomer Generation: Research, Policy, and Practice Perspectives. New York, NY: Haworth Press; 2006.

3. Kane RL, Kane RA. What older people want from long-term care, and how they can get it. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):114-127.

4. Bancroft J, Loftus J, Long JS. Distress about sex: a national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32(3):193-208.

Members of the baby boom generation (yes, my generation)—the nomenclature given to the 76 million people born between 1946 and 1964—are now in our 50s, 60s, and 70s. Many of us are enjoying our retirement while others are still working. Regardless of our circumstances, we all share one challenge: aging as comfortably as we can. It’s a fact of our lives that as we age, we battle risk factors for a variety of conditions, ranging from diabetes, heart disease, and Alzheimer disease to … sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Ever since I saw the statistics about increasing rates of STIs among older Americans, I’ve been mulling possible explanations for this trend. In conversation with my CR colleagues, the question arose as to whether the fact that the current population of senior citizens is comprised largely of Baby Boomers has had an impact. It’s certainly worth considering!

We (the Baby Boomers) are more savvy, assertive, health-conscious, and engaged in our health care than the generations that preceded us.1,2 When I look around at my friends and colleagues, I see a group of people who want to live more active lives and remain socially engaged—even as we manage our chronic conditions! As self-determining patients, we are likely to question established principles of medical care, demanding greater attention to our own definitions of health-related quality of life, including a satisfactory sex life.3

In fact, some of this increase in STIs among older Americans could be explained by the availability of treatments that address the sexual dysfunction that comes with aging. Previous generations of older adults have faced menopause and erectile dysfunction—but Baby Boomers are living and aging at a time when the symptoms can be more effectively managed. For older women, there are bioidentical hormones to replace those lost during menopause, which is often cited as the primary offender affecting their sexual lives (despite research suggesting that social and psychologic factors—emotional well-being, a strong emotional association with one’s partner, and positive body image—may be more foretelling of sexual activity later in life than the hormonal changes related to menopause).4

As for erectile dysfunction, yes, some men still feel awkward about bringing it up with their clinician; it can feel enfeebling for men to acknowledge, even though the physiologic changes are explained by the biology of aging (as we alluded to last week). Continuing sales of Viagra and Cialis suggest that boomer men are overcoming the stigmas of revealing their erectile dysfunction, however.

And maybe that is a contributing factor to this trend in STIs: We are being equipped for sexual performance, but perhaps we haven’t been adequately educated on what the consequences of our sexual encounters are. A lot of today’s seniors were already married when sex education gained prominence and perhaps missed the “safe sex” talks.

When I discussed this with a colleague of mine—a retired employee of the State Department—he noted that this topic was talked about even among US Embassy staff! At the risk of making a sweeping generalization and stating the obvious, he observed that “sexual mores have changed over time. Even many generations ago, they thought previous generations had been restrictive about sexual behavior!” Nevertheless, we agreed that the generation now emerging as “older Americans” grew up during the ’60s Free Love movement—and that philosophy seems to have carried into some individuals’ current sexual behavior. My colleague also noted that “as we get older, we lose partners—and sexual monogamy is lost with the loss of a partner.”

Continue to: The Baby Boomers...

The Baby Boomers are by far the most sexually liberal generation of older adults that this country has ever seen. Providing health care to this population requires addressing all health care needs, including sexual health and prevention. Next week, we’ll examine ways clinicians can comfortably broach these topics with older patients.

In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts: Is this the Second Spring of the Summer of Love generation? Whether you’re a Boomer or a Millennial or anyone in between, feel free to write to me at PAeditor@mdedge.com.

Members of the baby boom generation (yes, my generation)—the nomenclature given to the 76 million people born between 1946 and 1964—are now in our 50s, 60s, and 70s. Many of us are enjoying our retirement while others are still working. Regardless of our circumstances, we all share one challenge: aging as comfortably as we can. It’s a fact of our lives that as we age, we battle risk factors for a variety of conditions, ranging from diabetes, heart disease, and Alzheimer disease to … sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Ever since I saw the statistics about increasing rates of STIs among older Americans, I’ve been mulling possible explanations for this trend. In conversation with my CR colleagues, the question arose as to whether the fact that the current population of senior citizens is comprised largely of Baby Boomers has had an impact. It’s certainly worth considering!

We (the Baby Boomers) are more savvy, assertive, health-conscious, and engaged in our health care than the generations that preceded us.1,2 When I look around at my friends and colleagues, I see a group of people who want to live more active lives and remain socially engaged—even as we manage our chronic conditions! As self-determining patients, we are likely to question established principles of medical care, demanding greater attention to our own definitions of health-related quality of life, including a satisfactory sex life.3

In fact, some of this increase in STIs among older Americans could be explained by the availability of treatments that address the sexual dysfunction that comes with aging. Previous generations of older adults have faced menopause and erectile dysfunction—but Baby Boomers are living and aging at a time when the symptoms can be more effectively managed. For older women, there are bioidentical hormones to replace those lost during menopause, which is often cited as the primary offender affecting their sexual lives (despite research suggesting that social and psychologic factors—emotional well-being, a strong emotional association with one’s partner, and positive body image—may be more foretelling of sexual activity later in life than the hormonal changes related to menopause).4

As for erectile dysfunction, yes, some men still feel awkward about bringing it up with their clinician; it can feel enfeebling for men to acknowledge, even though the physiologic changes are explained by the biology of aging (as we alluded to last week). Continuing sales of Viagra and Cialis suggest that boomer men are overcoming the stigmas of revealing their erectile dysfunction, however.

And maybe that is a contributing factor to this trend in STIs: We are being equipped for sexual performance, but perhaps we haven’t been adequately educated on what the consequences of our sexual encounters are. A lot of today’s seniors were already married when sex education gained prominence and perhaps missed the “safe sex” talks.

When I discussed this with a colleague of mine—a retired employee of the State Department—he noted that this topic was talked about even among US Embassy staff! At the risk of making a sweeping generalization and stating the obvious, he observed that “sexual mores have changed over time. Even many generations ago, they thought previous generations had been restrictive about sexual behavior!” Nevertheless, we agreed that the generation now emerging as “older Americans” grew up during the ’60s Free Love movement—and that philosophy seems to have carried into some individuals’ current sexual behavior. My colleague also noted that “as we get older, we lose partners—and sexual monogamy is lost with the loss of a partner.”

Continue to: The Baby Boomers...

The Baby Boomers are by far the most sexually liberal generation of older adults that this country has ever seen. Providing health care to this population requires addressing all health care needs, including sexual health and prevention. Next week, we’ll examine ways clinicians can comfortably broach these topics with older patients.

In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts: Is this the Second Spring of the Summer of Love generation? Whether you’re a Boomer or a Millennial or anyone in between, feel free to write to me at PAeditor@mdedge.com.

1. Kickbusch I, Payne L. Twenty-first century health promotion: the public health revolution meets the wellness revolution. Health Promot Int. 2003;18(4):275-278.

2. Wilson LB, Simson SP (eds). Civic Engagement and the Baby Boomer Generation: Research, Policy, and Practice Perspectives. New York, NY: Haworth Press; 2006.

3. Kane RL, Kane RA. What older people want from long-term care, and how they can get it. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):114-127.

4. Bancroft J, Loftus J, Long JS. Distress about sex: a national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32(3):193-208.

1. Kickbusch I, Payne L. Twenty-first century health promotion: the public health revolution meets the wellness revolution. Health Promot Int. 2003;18(4):275-278.

2. Wilson LB, Simson SP (eds). Civic Engagement and the Baby Boomer Generation: Research, Policy, and Practice Perspectives. New York, NY: Haworth Press; 2006.

3. Kane RL, Kane RA. What older people want from long-term care, and how they can get it. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):114-127.

4. Bancroft J, Loftus J, Long JS. Distress about sex: a national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32(3):193-208.

Part 2: Why the Increase?

As established last week, there has been a startling increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among older adults in the United States. The burning question on everyone’s mind (certainly mine!) is: Why? Engaging in some “educated speculation” yields many factors possibly driving this trend. For example:

1. Provider Reluctance. Older Americans may not get regular screenings for STIs because their health care providers are often reluctant to raise the issue. That may be fueled by lack of awareness on the clinician’s part: More than 60% of individuals older than 60 have sex at least once a month, yet this population is rarely considered to be “at risk” for STIs.1

2. Patient Embarrassment/awkwardness. For many older Americans, admitting that they are having sex makes them feel awkward or embarrassed. Reluctance to share intimate details means they may not seek evaluation and treatment for symptoms that seem related to their sexual health or activity.

3. Effects of Aging. There are 2 sides to this coin: actual physiologic changes that occur with age and assumptions that all changes are just part of aging. As people get older, their immune systems tend to deteriorate, making them more vulnerable to contracting any disease—including STIs. After menopause, women's vaginal tissues thin and natural lubrication declines, increasing their risk for microtears that can leave them susceptible to infectious organisms. And let’s be honest: Some STI symptoms, such as fatigue, weakness, and changes in memory, are nonspecific and may be mistaken by clinicians for the regular progression of age.2

4. Social Changes. The world has changed since most older adults last dove into the dating pool. We now have online dating services, some of which cater to a mature audience; as a result, people may be less familiar with their partner’s sexual history. Compounding that, many older adults just aren’t accustomed to thinking of themselves or a partner as being at high risk for STIs—and if you don’t even think about it, you definitely won’t ask. Widowed or divorced adults may date more than one person at a time, raising their risk for infection after a long period of monogamy. Seniors also may not be accustomed to using a condom or do not use one because they think the risk for STIs is minimal or nonexistent. Seniors may not consider oral or anal sex as a way of contracting or transmitting STIs.3

5. Medical Advances. Compared with previous generations, today’s seniors have an easier time having sex at an older age, thanks to the availability of medications such as sildenafil (Viagra) and tadalafil (Cialis) for men with erectile dysfunction. There has also been an increase in postmenopausal women requesting and receiving bioidentical hormone replacement. With increased libido and ability to perform come more sexual encounters among the older population—and as a result, more opportunities for STIs to spread. Are there other reasons for the increase in STIs in this population? Next week we’ll consider the unique societal influences of the Baby Boom generation. In the meantime, please share your insights with me at PAeditor@mdedge.com.

1. Boskey E. STDs in the elderly community. Verywell Health. February 14, 2018. www.verywellhealth.com/stds-the-elderly-3133189. Accessed May 8, 2019.

2. East A. (2017). Seniors and STDs: common sexually transmitted diseases. CaringPeople. June 23, 2017. https://caringpeopleinc.com/blog/seniors-common-sexually-transmitted-diseases. Accessed May 8, 2019.

3. Harvard Medical School. Sexually transmitted disease? At my age? Harvard Health Letter. February 2018. www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/sexually-transmitted-disease-at-my-age. Accessed May 8, 2019.

As established last week, there has been a startling increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among older adults in the United States. The burning question on everyone’s mind (certainly mine!) is: Why? Engaging in some “educated speculation” yields many factors possibly driving this trend. For example:

1. Provider Reluctance. Older Americans may not get regular screenings for STIs because their health care providers are often reluctant to raise the issue. That may be fueled by lack of awareness on the clinician’s part: More than 60% of individuals older than 60 have sex at least once a month, yet this population is rarely considered to be “at risk” for STIs.1

2. Patient Embarrassment/awkwardness. For many older Americans, admitting that they are having sex makes them feel awkward or embarrassed. Reluctance to share intimate details means they may not seek evaluation and treatment for symptoms that seem related to their sexual health or activity.

3. Effects of Aging. There are 2 sides to this coin: actual physiologic changes that occur with age and assumptions that all changes are just part of aging. As people get older, their immune systems tend to deteriorate, making them more vulnerable to contracting any disease—including STIs. After menopause, women's vaginal tissues thin and natural lubrication declines, increasing their risk for microtears that can leave them susceptible to infectious organisms. And let’s be honest: Some STI symptoms, such as fatigue, weakness, and changes in memory, are nonspecific and may be mistaken by clinicians for the regular progression of age.2

4. Social Changes. The world has changed since most older adults last dove into the dating pool. We now have online dating services, some of which cater to a mature audience; as a result, people may be less familiar with their partner’s sexual history. Compounding that, many older adults just aren’t accustomed to thinking of themselves or a partner as being at high risk for STIs—and if you don’t even think about it, you definitely won’t ask. Widowed or divorced adults may date more than one person at a time, raising their risk for infection after a long period of monogamy. Seniors also may not be accustomed to using a condom or do not use one because they think the risk for STIs is minimal or nonexistent. Seniors may not consider oral or anal sex as a way of contracting or transmitting STIs.3

5. Medical Advances. Compared with previous generations, today’s seniors have an easier time having sex at an older age, thanks to the availability of medications such as sildenafil (Viagra) and tadalafil (Cialis) for men with erectile dysfunction. There has also been an increase in postmenopausal women requesting and receiving bioidentical hormone replacement. With increased libido and ability to perform come more sexual encounters among the older population—and as a result, more opportunities for STIs to spread. Are there other reasons for the increase in STIs in this population? Next week we’ll consider the unique societal influences of the Baby Boom generation. In the meantime, please share your insights with me at PAeditor@mdedge.com.

As established last week, there has been a startling increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among older adults in the United States. The burning question on everyone’s mind (certainly mine!) is: Why? Engaging in some “educated speculation” yields many factors possibly driving this trend. For example:

1. Provider Reluctance. Older Americans may not get regular screenings for STIs because their health care providers are often reluctant to raise the issue. That may be fueled by lack of awareness on the clinician’s part: More than 60% of individuals older than 60 have sex at least once a month, yet this population is rarely considered to be “at risk” for STIs.1

2. Patient Embarrassment/awkwardness. For many older Americans, admitting that they are having sex makes them feel awkward or embarrassed. Reluctance to share intimate details means they may not seek evaluation and treatment for symptoms that seem related to their sexual health or activity.

3. Effects of Aging. There are 2 sides to this coin: actual physiologic changes that occur with age and assumptions that all changes are just part of aging. As people get older, their immune systems tend to deteriorate, making them more vulnerable to contracting any disease—including STIs. After menopause, women's vaginal tissues thin and natural lubrication declines, increasing their risk for microtears that can leave them susceptible to infectious organisms. And let’s be honest: Some STI symptoms, such as fatigue, weakness, and changes in memory, are nonspecific and may be mistaken by clinicians for the regular progression of age.2

4. Social Changes. The world has changed since most older adults last dove into the dating pool. We now have online dating services, some of which cater to a mature audience; as a result, people may be less familiar with their partner’s sexual history. Compounding that, many older adults just aren’t accustomed to thinking of themselves or a partner as being at high risk for STIs—and if you don’t even think about it, you definitely won’t ask. Widowed or divorced adults may date more than one person at a time, raising their risk for infection after a long period of monogamy. Seniors also may not be accustomed to using a condom or do not use one because they think the risk for STIs is minimal or nonexistent. Seniors may not consider oral or anal sex as a way of contracting or transmitting STIs.3

5. Medical Advances. Compared with previous generations, today’s seniors have an easier time having sex at an older age, thanks to the availability of medications such as sildenafil (Viagra) and tadalafil (Cialis) for men with erectile dysfunction. There has also been an increase in postmenopausal women requesting and receiving bioidentical hormone replacement. With increased libido and ability to perform come more sexual encounters among the older population—and as a result, more opportunities for STIs to spread. Are there other reasons for the increase in STIs in this population? Next week we’ll consider the unique societal influences of the Baby Boom generation. In the meantime, please share your insights with me at PAeditor@mdedge.com.

1. Boskey E. STDs in the elderly community. Verywell Health. February 14, 2018. www.verywellhealth.com/stds-the-elderly-3133189. Accessed May 8, 2019.

2. East A. (2017). Seniors and STDs: common sexually transmitted diseases. CaringPeople. June 23, 2017. https://caringpeopleinc.com/blog/seniors-common-sexually-transmitted-diseases. Accessed May 8, 2019.

3. Harvard Medical School. Sexually transmitted disease? At my age? Harvard Health Letter. February 2018. www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/sexually-transmitted-disease-at-my-age. Accessed May 8, 2019.

1. Boskey E. STDs in the elderly community. Verywell Health. February 14, 2018. www.verywellhealth.com/stds-the-elderly-3133189. Accessed May 8, 2019.

2. East A. (2017). Seniors and STDs: common sexually transmitted diseases. CaringPeople. June 23, 2017. https://caringpeopleinc.com/blog/seniors-common-sexually-transmitted-diseases. Accessed May 8, 2019.

3. Harvard Medical School. Sexually transmitted disease? At my age? Harvard Health Letter. February 2018. www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/sexually-transmitted-disease-at-my-age. Accessed May 8, 2019.

Part 1: A Disturbing Trend

While reviewing some epidemiology data for a lecture recently, I couldn’t believe my eyes: The numbers indicated an increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among older Americans. Filled with doubt about the accuracy, I decided to research further. My first stop was a PA colleague who works with a mobile urgent care company that specializes in retirement communities—and she confirmed that she has witnessed this “trend”!

The fundamental public health concern for older Americans is, of course, long-term illness, disability, and dependency on others. However, experts on aging agree that since the last century, disability rates among those older than 65 have declined, as have the number of seniors living in nursing homes. Suffice it to say, the good news is that Americans are living longer—the bad news, they are doing so with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and malignant neoplasms. The other downside is that seniors have increased risk for infectious diseases.1

Healthy People 2020 continues to recognize HIV and other STIs as problems in the United States and to promote efforts to reduce them. Unfortunately, prevention strategies for older adults in primary care settings are often not aimed at these diseases. More broadly, sexual behaviors tend to be discussed less with this population.2

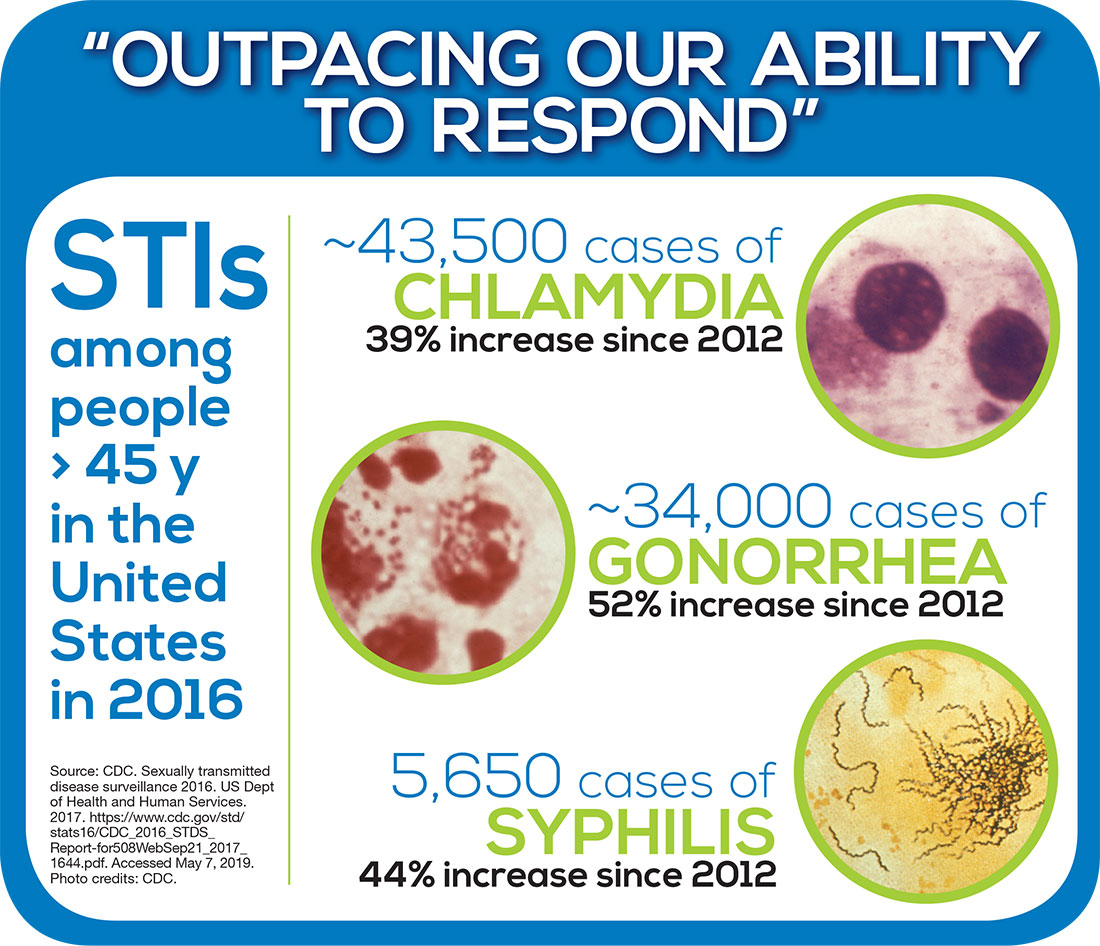

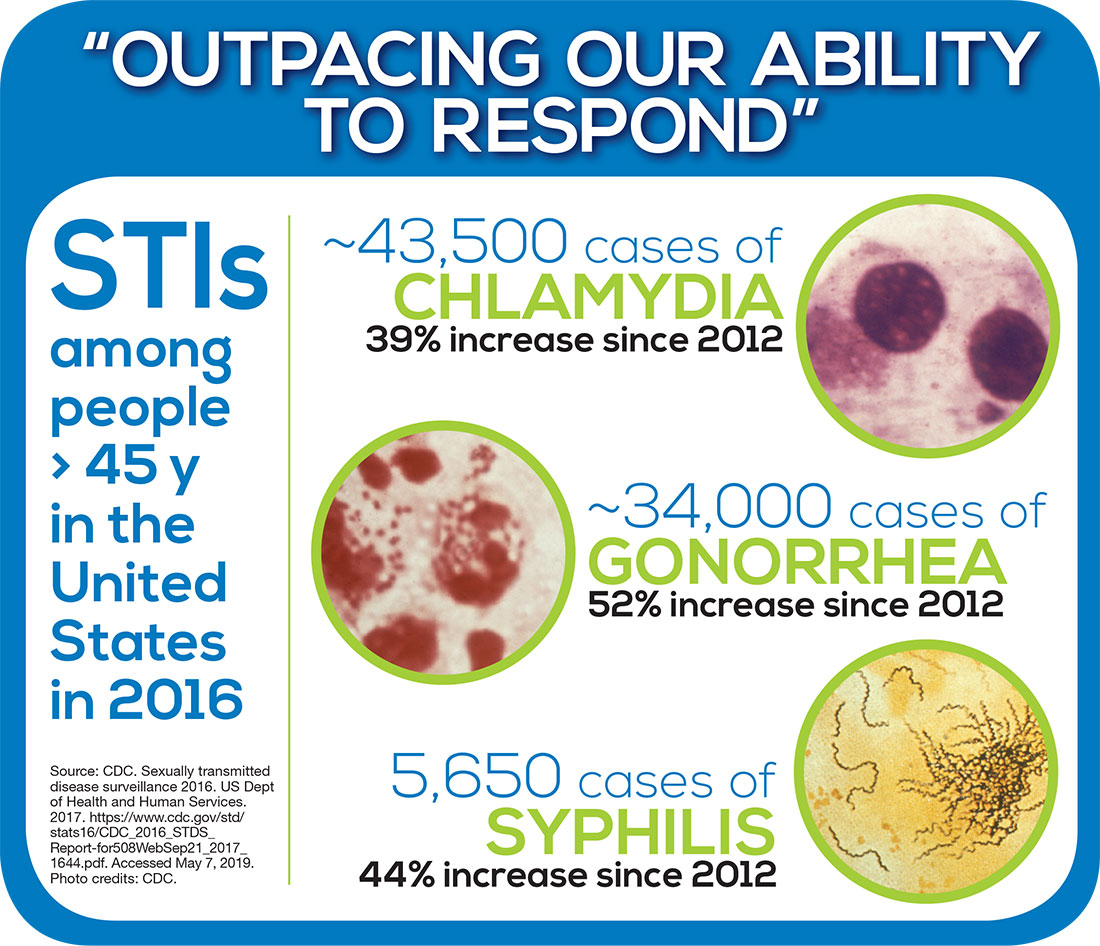

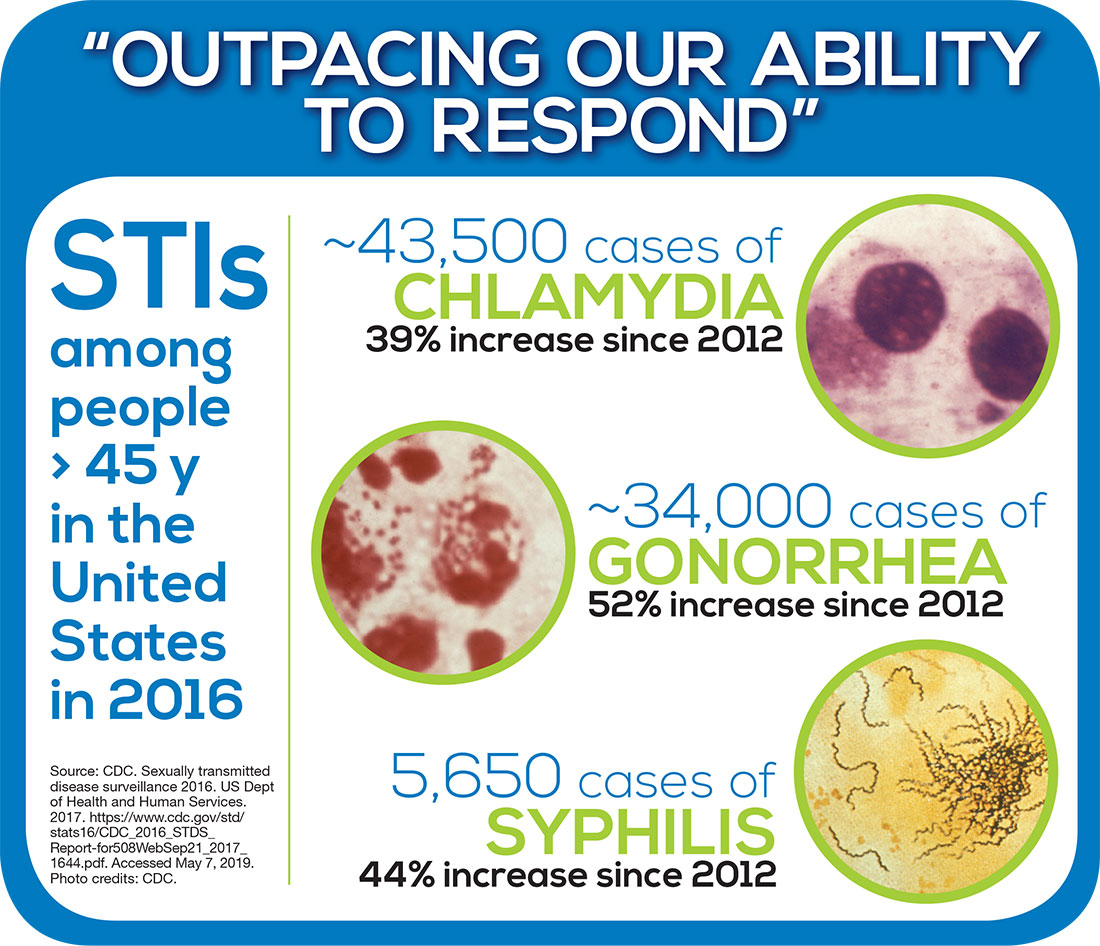

The disturbing climb in STIs among older Americans is part of a more momentous national trend that the CDC says must be tackled. Overall rates of STIs in 2016 were the highest ever recorded in a single year.3 And although STI rates are highest among people ages 15 to 24, the upsurge among older Americans is larger than it is for the rest of the US population. According to the CDC, in 2016, there were 82,938 cases of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia reported among Americans ages 45 and older—about a 20% percent increase from 2015 and continuing a trend of annual increases since at least 2012.3 The infographic shows the rates for individual STIs.

The CDC notes that STIs put people “at risk for severe, lifelong health outcomes like chronic pain, severe reproductive health complications, and HIV" particularly if left untreated.4 Jonathan Mermin, MD, Director of the CDC National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention has described STIs as “a persistent enemy, growing in number and outpacing our ability to respond.”5

Over the next 3 weeks, we will explore this public health issue—starting next week with the big question: Why is this trend occurring? In the meantime, feel free to share your thoughts with me at PAeditor@mdedge.com. See you next Thursday!

1. Schneider M. Introduction to Public Health. 5th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2017.

2. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020: Sexually transmitted diseases. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/sexually-transmitted-diseases. Accessed May 6, 2019.

3. CDC. 2016 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/default.htm. Accessed May 6, 2019.

4. CDC. Fact sheet: reported STDs in the United States, 2017. www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/std-trends-508.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2019.

5. CDC National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. STDs at record high, indicating urgent need for prevention [press release]. September 26, 2017. www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2017/std-surveillance-report-2016-press-release.html. Accessed May 6, 2019.

While reviewing some epidemiology data for a lecture recently, I couldn’t believe my eyes: The numbers indicated an increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among older Americans. Filled with doubt about the accuracy, I decided to research further. My first stop was a PA colleague who works with a mobile urgent care company that specializes in retirement communities—and she confirmed that she has witnessed this “trend”!

The fundamental public health concern for older Americans is, of course, long-term illness, disability, and dependency on others. However, experts on aging agree that since the last century, disability rates among those older than 65 have declined, as have the number of seniors living in nursing homes. Suffice it to say, the good news is that Americans are living longer—the bad news, they are doing so with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and malignant neoplasms. The other downside is that seniors have increased risk for infectious diseases.1

Healthy People 2020 continues to recognize HIV and other STIs as problems in the United States and to promote efforts to reduce them. Unfortunately, prevention strategies for older adults in primary care settings are often not aimed at these diseases. More broadly, sexual behaviors tend to be discussed less with this population.2

The disturbing climb in STIs among older Americans is part of a more momentous national trend that the CDC says must be tackled. Overall rates of STIs in 2016 were the highest ever recorded in a single year.3 And although STI rates are highest among people ages 15 to 24, the upsurge among older Americans is larger than it is for the rest of the US population. According to the CDC, in 2016, there were 82,938 cases of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia reported among Americans ages 45 and older—about a 20% percent increase from 2015 and continuing a trend of annual increases since at least 2012.3 The infographic shows the rates for individual STIs.

The CDC notes that STIs put people “at risk for severe, lifelong health outcomes like chronic pain, severe reproductive health complications, and HIV" particularly if left untreated.4 Jonathan Mermin, MD, Director of the CDC National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention has described STIs as “a persistent enemy, growing in number and outpacing our ability to respond.”5

Over the next 3 weeks, we will explore this public health issue—starting next week with the big question: Why is this trend occurring? In the meantime, feel free to share your thoughts with me at PAeditor@mdedge.com. See you next Thursday!

While reviewing some epidemiology data for a lecture recently, I couldn’t believe my eyes: The numbers indicated an increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among older Americans. Filled with doubt about the accuracy, I decided to research further. My first stop was a PA colleague who works with a mobile urgent care company that specializes in retirement communities—and she confirmed that she has witnessed this “trend”!

The fundamental public health concern for older Americans is, of course, long-term illness, disability, and dependency on others. However, experts on aging agree that since the last century, disability rates among those older than 65 have declined, as have the number of seniors living in nursing homes. Suffice it to say, the good news is that Americans are living longer—the bad news, they are doing so with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and malignant neoplasms. The other downside is that seniors have increased risk for infectious diseases.1

Healthy People 2020 continues to recognize HIV and other STIs as problems in the United States and to promote efforts to reduce them. Unfortunately, prevention strategies for older adults in primary care settings are often not aimed at these diseases. More broadly, sexual behaviors tend to be discussed less with this population.2

The disturbing climb in STIs among older Americans is part of a more momentous national trend that the CDC says must be tackled. Overall rates of STIs in 2016 were the highest ever recorded in a single year.3 And although STI rates are highest among people ages 15 to 24, the upsurge among older Americans is larger than it is for the rest of the US population. According to the CDC, in 2016, there were 82,938 cases of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia reported among Americans ages 45 and older—about a 20% percent increase from 2015 and continuing a trend of annual increases since at least 2012.3 The infographic shows the rates for individual STIs.

The CDC notes that STIs put people “at risk for severe, lifelong health outcomes like chronic pain, severe reproductive health complications, and HIV" particularly if left untreated.4 Jonathan Mermin, MD, Director of the CDC National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention has described STIs as “a persistent enemy, growing in number and outpacing our ability to respond.”5

Over the next 3 weeks, we will explore this public health issue—starting next week with the big question: Why is this trend occurring? In the meantime, feel free to share your thoughts with me at PAeditor@mdedge.com. See you next Thursday!

1. Schneider M. Introduction to Public Health. 5th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2017.

2. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020: Sexually transmitted diseases. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/sexually-transmitted-diseases. Accessed May 6, 2019.

3. CDC. 2016 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/default.htm. Accessed May 6, 2019.

4. CDC. Fact sheet: reported STDs in the United States, 2017. www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/std-trends-508.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2019.

5. CDC National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. STDs at record high, indicating urgent need for prevention [press release]. September 26, 2017. www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2017/std-surveillance-report-2016-press-release.html. Accessed May 6, 2019.

1. Schneider M. Introduction to Public Health. 5th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2017.

2. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020: Sexually transmitted diseases. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/sexually-transmitted-diseases. Accessed May 6, 2019.

3. CDC. 2016 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/default.htm. Accessed May 6, 2019.

4. CDC. Fact sheet: reported STDs in the United States, 2017. www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/std-trends-508.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2019.

5. CDC National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. STDs at record high, indicating urgent need for prevention [press release]. September 26, 2017. www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2017/std-surveillance-report-2016-press-release.html. Accessed May 6, 2019.

Working With Parents to Vaccinate Children

Global outbreaks of infectious diseases—such as smallpox, pertussis, dysentery, and scarlet fever—seem like fodder for the history books. It was centuries ago that epidemics wiped out large swathes of the world population. Many people living and raising children today have never witnessed the devastating effects of measles, mumps, polio, and influenza—diseases that have been substantially reduced or even eradicated.1 Why? Because since the early 1900s, we have had scientifically developed and widely distributed vaccines at our disposal.

In context, it is incredible to realize that we are still in the beginning stages of vaccine research and development. From that perspective, it is perhaps not as surprising that some parents are hesitant to vaccinate their children—after all, do we really know everything we can and should know about inoculation? Parental resistance to or refusal of vaccination is further fueled by tainted research (Andrew Wakefield was forced to retract his findings that “validated” a link between thimerosal in vaccines and autism) and misinformation propagated on the Internet.2

But what has long been a source of frustration to those who support routine vaccination has, in recent years, started to become a public health issue. Measles outbreaks are no longer historical artifacts—they are real, as evidenced by the current rise in cases centered in Clark County, Washington. Through the first full week of February 2019, there were 101 confirmed cases of measles in the US, half of which occurred in Washington State—leading the governor to declare a public health emergency.3

This has, of course, reinvigorated the ongoing discussion about parental refusal to vaccinate. Enough has been said on this topic, by both public officials and private individuals, in a variety of venues over the years. So I’d like to focus instead on the role that individual health care providers can play in this situation.

Over the years, many of my colleagues have shared stories about parents who have refused to vaccinate their children. We know many things: These parents often fear complications from vaccination more than complications of disease. Many have religious or philosophical reasons for their reluctance or refusal to vaccinate their children. Some have concerns about vaccine safety or effectiveness. We know these things … but we don’t always know how to speak with parents about these issues.

It is somewhat ironic that the core motivation for hesitant parents and well-meaning clinicians is the same: care and protection of the child. The difficulty lies in the disparate view of what that entails. As NPs and PAs, though, our duty is to seek health benefits for and minimize harm to the patients in our care. Part of our role, when those patients are children, is to provide parents with the necessary risk-benefit information to help them make informed decisions. When the subject is vaccination, we must listen carefully and be respectful of parents’ concerns; we must recognize that their decision-making criteria may differ from ours.

So how can we bridge the gap with parents who “don’t see it the way we do”? We start by being honest with them about what is and isn’t known as far as the risks and benefits of vaccination in general or a vaccine in particular. This means acknowledging that although vaccines are very safe, they are not risk-free or 100% effective. But this also gives us the opportunity to provide them with validated data and to emphasize that the risks of any vaccine should not be considered in a silo but rather in comparison with the risks of the disease in question or of the lack of immunization.

Continue to: Helpfully, Leask and colleagues...

Helpfully, Leask and colleagues have classified parental positions on vaccination, which also provided the groundwork to offer strategies for communicating with each group.4 They identified five classes:

Unquestioning acceptors (30% to 40% of parents), who vaccinate their children and typically have no specific questions about the need for or safety of vaccines. Since this group tends to have a good relationship with their health care team but less detailed knowledge about vaccination, clinicians should continue to build rapport while providing scientific information about the vaccine being recommended or administered.4

Cautious acceptors (25% to 35%), who vaccinate their children despite having minor concerns. They tend to recognize the risk for adverse effects and hope their child will not be affected. In addition to building rapport, clinicians should provide verbal and numeric descriptions of relevant vaccine data and explain common adverse effects and disease risks.4

Hesitant vaccinators (20% to 30%), who are on the fence about the benefits and safety of vaccination. Their focus is more on the negative aspects, and they may not feel particularly trusting of their health care provider. Therefore, gaining trust is vital—parents in this group are eager to discuss their concerns with their clinician and have their questions answered satisfactorily. Motivational interviewing using a guiding style may be a helpful tool.4

Late or selective vaccinators (2% to 27%), who have significant doubts about the safety and necessity of vaccines, resulting in their choice to delay vaccination or select only some of the recommended vaccines for their child. These parents may require additional time—possibly a second appointment—in which to fully discuss their concerns. Be sure to provide up-to-date information on the risks and benefits of a vaccine, and use decision aids as appropriate.4

Continue to: Refusers...

Refusers (<2%), who have concerns about the number of vaccines children receive and conflicting feelings about whom to trust and how best to get answers to their questions. This group tends to demonstrate high knowledge levels about vaccination but may be the most argumentative when presented with information. Emphasize the importance of protecting the child from an infectious disease and reinforce the effectiveness of the vaccine. Use statistics rather than anecdotes. But above all, spend the time needed to provide refusers with a thorough understanding of the risks of not immunizing their child.4

Although it is not a universal sentiment, many parents confer trust on their health care providers. We can use this trust in a respectful, noncoercive, and non-condescending manner by providing research-supported facts about vaccines. Clinicians who listen with a compassionate ear will be in the best position to lead the hesitant, late or selective, or refusing parents to confidently make an informed decision that immunization is the best way to protect their children from vaccine-preventable diseases.4

Rather than yet again focusing on the negative, I’d like to ask: Have you had a success story of helping parents to choose vaccination for their children? How did you overcome their concerns? Share your experience with me at PAeditor@mdege.com.

1. CDC. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999 impact of vaccines universally recommended for children—United States, 1990-1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):243-248.

2. Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, et al. RETRACTED: Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet. 1998;351(9103):637-641.

3. Franki R. United States now over 100 measles cases for the year. MDEdge Family Practice. February 11, 2019.

4. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12:154.

Global outbreaks of infectious diseases—such as smallpox, pertussis, dysentery, and scarlet fever—seem like fodder for the history books. It was centuries ago that epidemics wiped out large swathes of the world population. Many people living and raising children today have never witnessed the devastating effects of measles, mumps, polio, and influenza—diseases that have been substantially reduced or even eradicated.1 Why? Because since the early 1900s, we have had scientifically developed and widely distributed vaccines at our disposal.

In context, it is incredible to realize that we are still in the beginning stages of vaccine research and development. From that perspective, it is perhaps not as surprising that some parents are hesitant to vaccinate their children—after all, do we really know everything we can and should know about inoculation? Parental resistance to or refusal of vaccination is further fueled by tainted research (Andrew Wakefield was forced to retract his findings that “validated” a link between thimerosal in vaccines and autism) and misinformation propagated on the Internet.2

But what has long been a source of frustration to those who support routine vaccination has, in recent years, started to become a public health issue. Measles outbreaks are no longer historical artifacts—they are real, as evidenced by the current rise in cases centered in Clark County, Washington. Through the first full week of February 2019, there were 101 confirmed cases of measles in the US, half of which occurred in Washington State—leading the governor to declare a public health emergency.3

This has, of course, reinvigorated the ongoing discussion about parental refusal to vaccinate. Enough has been said on this topic, by both public officials and private individuals, in a variety of venues over the years. So I’d like to focus instead on the role that individual health care providers can play in this situation.

Over the years, many of my colleagues have shared stories about parents who have refused to vaccinate their children. We know many things: These parents often fear complications from vaccination more than complications of disease. Many have religious or philosophical reasons for their reluctance or refusal to vaccinate their children. Some have concerns about vaccine safety or effectiveness. We know these things … but we don’t always know how to speak with parents about these issues.

It is somewhat ironic that the core motivation for hesitant parents and well-meaning clinicians is the same: care and protection of the child. The difficulty lies in the disparate view of what that entails. As NPs and PAs, though, our duty is to seek health benefits for and minimize harm to the patients in our care. Part of our role, when those patients are children, is to provide parents with the necessary risk-benefit information to help them make informed decisions. When the subject is vaccination, we must listen carefully and be respectful of parents’ concerns; we must recognize that their decision-making criteria may differ from ours.

So how can we bridge the gap with parents who “don’t see it the way we do”? We start by being honest with them about what is and isn’t known as far as the risks and benefits of vaccination in general or a vaccine in particular. This means acknowledging that although vaccines are very safe, they are not risk-free or 100% effective. But this also gives us the opportunity to provide them with validated data and to emphasize that the risks of any vaccine should not be considered in a silo but rather in comparison with the risks of the disease in question or of the lack of immunization.

Continue to: Helpfully, Leask and colleagues...

Helpfully, Leask and colleagues have classified parental positions on vaccination, which also provided the groundwork to offer strategies for communicating with each group.4 They identified five classes:

Unquestioning acceptors (30% to 40% of parents), who vaccinate their children and typically have no specific questions about the need for or safety of vaccines. Since this group tends to have a good relationship with their health care team but less detailed knowledge about vaccination, clinicians should continue to build rapport while providing scientific information about the vaccine being recommended or administered.4

Cautious acceptors (25% to 35%), who vaccinate their children despite having minor concerns. They tend to recognize the risk for adverse effects and hope their child will not be affected. In addition to building rapport, clinicians should provide verbal and numeric descriptions of relevant vaccine data and explain common adverse effects and disease risks.4

Hesitant vaccinators (20% to 30%), who are on the fence about the benefits and safety of vaccination. Their focus is more on the negative aspects, and they may not feel particularly trusting of their health care provider. Therefore, gaining trust is vital—parents in this group are eager to discuss their concerns with their clinician and have their questions answered satisfactorily. Motivational interviewing using a guiding style may be a helpful tool.4

Late or selective vaccinators (2% to 27%), who have significant doubts about the safety and necessity of vaccines, resulting in their choice to delay vaccination or select only some of the recommended vaccines for their child. These parents may require additional time—possibly a second appointment—in which to fully discuss their concerns. Be sure to provide up-to-date information on the risks and benefits of a vaccine, and use decision aids as appropriate.4

Continue to: Refusers...

Refusers (<2%), who have concerns about the number of vaccines children receive and conflicting feelings about whom to trust and how best to get answers to their questions. This group tends to demonstrate high knowledge levels about vaccination but may be the most argumentative when presented with information. Emphasize the importance of protecting the child from an infectious disease and reinforce the effectiveness of the vaccine. Use statistics rather than anecdotes. But above all, spend the time needed to provide refusers with a thorough understanding of the risks of not immunizing their child.4

Although it is not a universal sentiment, many parents confer trust on their health care providers. We can use this trust in a respectful, noncoercive, and non-condescending manner by providing research-supported facts about vaccines. Clinicians who listen with a compassionate ear will be in the best position to lead the hesitant, late or selective, or refusing parents to confidently make an informed decision that immunization is the best way to protect their children from vaccine-preventable diseases.4

Rather than yet again focusing on the negative, I’d like to ask: Have you had a success story of helping parents to choose vaccination for their children? How did you overcome their concerns? Share your experience with me at PAeditor@mdege.com.

Global outbreaks of infectious diseases—such as smallpox, pertussis, dysentery, and scarlet fever—seem like fodder for the history books. It was centuries ago that epidemics wiped out large swathes of the world population. Many people living and raising children today have never witnessed the devastating effects of measles, mumps, polio, and influenza—diseases that have been substantially reduced or even eradicated.1 Why? Because since the early 1900s, we have had scientifically developed and widely distributed vaccines at our disposal.

In context, it is incredible to realize that we are still in the beginning stages of vaccine research and development. From that perspective, it is perhaps not as surprising that some parents are hesitant to vaccinate their children—after all, do we really know everything we can and should know about inoculation? Parental resistance to or refusal of vaccination is further fueled by tainted research (Andrew Wakefield was forced to retract his findings that “validated” a link between thimerosal in vaccines and autism) and misinformation propagated on the Internet.2

But what has long been a source of frustration to those who support routine vaccination has, in recent years, started to become a public health issue. Measles outbreaks are no longer historical artifacts—they are real, as evidenced by the current rise in cases centered in Clark County, Washington. Through the first full week of February 2019, there were 101 confirmed cases of measles in the US, half of which occurred in Washington State—leading the governor to declare a public health emergency.3

This has, of course, reinvigorated the ongoing discussion about parental refusal to vaccinate. Enough has been said on this topic, by both public officials and private individuals, in a variety of venues over the years. So I’d like to focus instead on the role that individual health care providers can play in this situation.

Over the years, many of my colleagues have shared stories about parents who have refused to vaccinate their children. We know many things: These parents often fear complications from vaccination more than complications of disease. Many have religious or philosophical reasons for their reluctance or refusal to vaccinate their children. Some have concerns about vaccine safety or effectiveness. We know these things … but we don’t always know how to speak with parents about these issues.

It is somewhat ironic that the core motivation for hesitant parents and well-meaning clinicians is the same: care and protection of the child. The difficulty lies in the disparate view of what that entails. As NPs and PAs, though, our duty is to seek health benefits for and minimize harm to the patients in our care. Part of our role, when those patients are children, is to provide parents with the necessary risk-benefit information to help them make informed decisions. When the subject is vaccination, we must listen carefully and be respectful of parents’ concerns; we must recognize that their decision-making criteria may differ from ours.

So how can we bridge the gap with parents who “don’t see it the way we do”? We start by being honest with them about what is and isn’t known as far as the risks and benefits of vaccination in general or a vaccine in particular. This means acknowledging that although vaccines are very safe, they are not risk-free or 100% effective. But this also gives us the opportunity to provide them with validated data and to emphasize that the risks of any vaccine should not be considered in a silo but rather in comparison with the risks of the disease in question or of the lack of immunization.

Continue to: Helpfully, Leask and colleagues...

Helpfully, Leask and colleagues have classified parental positions on vaccination, which also provided the groundwork to offer strategies for communicating with each group.4 They identified five classes:

Unquestioning acceptors (30% to 40% of parents), who vaccinate their children and typically have no specific questions about the need for or safety of vaccines. Since this group tends to have a good relationship with their health care team but less detailed knowledge about vaccination, clinicians should continue to build rapport while providing scientific information about the vaccine being recommended or administered.4

Cautious acceptors (25% to 35%), who vaccinate their children despite having minor concerns. They tend to recognize the risk for adverse effects and hope their child will not be affected. In addition to building rapport, clinicians should provide verbal and numeric descriptions of relevant vaccine data and explain common adverse effects and disease risks.4

Hesitant vaccinators (20% to 30%), who are on the fence about the benefits and safety of vaccination. Their focus is more on the negative aspects, and they may not feel particularly trusting of their health care provider. Therefore, gaining trust is vital—parents in this group are eager to discuss their concerns with their clinician and have their questions answered satisfactorily. Motivational interviewing using a guiding style may be a helpful tool.4

Late or selective vaccinators (2% to 27%), who have significant doubts about the safety and necessity of vaccines, resulting in their choice to delay vaccination or select only some of the recommended vaccines for their child. These parents may require additional time—possibly a second appointment—in which to fully discuss their concerns. Be sure to provide up-to-date information on the risks and benefits of a vaccine, and use decision aids as appropriate.4

Continue to: Refusers...

Refusers (<2%), who have concerns about the number of vaccines children receive and conflicting feelings about whom to trust and how best to get answers to their questions. This group tends to demonstrate high knowledge levels about vaccination but may be the most argumentative when presented with information. Emphasize the importance of protecting the child from an infectious disease and reinforce the effectiveness of the vaccine. Use statistics rather than anecdotes. But above all, spend the time needed to provide refusers with a thorough understanding of the risks of not immunizing their child.4

Although it is not a universal sentiment, many parents confer trust on their health care providers. We can use this trust in a respectful, noncoercive, and non-condescending manner by providing research-supported facts about vaccines. Clinicians who listen with a compassionate ear will be in the best position to lead the hesitant, late or selective, or refusing parents to confidently make an informed decision that immunization is the best way to protect their children from vaccine-preventable diseases.4

Rather than yet again focusing on the negative, I’d like to ask: Have you had a success story of helping parents to choose vaccination for their children? How did you overcome their concerns? Share your experience with me at PAeditor@mdege.com.

1. CDC. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999 impact of vaccines universally recommended for children—United States, 1990-1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):243-248.

2. Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, et al. RETRACTED: Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet. 1998;351(9103):637-641.

3. Franki R. United States now over 100 measles cases for the year. MDEdge Family Practice. February 11, 2019.

4. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12:154.

1. CDC. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999 impact of vaccines universally recommended for children—United States, 1990-1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):243-248.

2. Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, et al. RETRACTED: Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet. 1998;351(9103):637-641.

3. Franki R. United States now over 100 measles cases for the year. MDEdge Family Practice. February 11, 2019.

4. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12:154.

OTP: Pipe Dream, Smoke Screen, or the Right Thing?

We live in a world of acronyms. OMG, GOAT, and the like are ubiquitous on social media and increasingly sprinkled into more traditional journalistic formats. But if you’re a PA, the most important acronym for at least the past two years has been OTP—optimal team practice.

In my February 2017 editorial, I opined on the related concept of full practice authority (FPA), discussing the hurdles the NP and PA professions face to achieve this goal (Clinician Reviews. 2017;27[2]:12-14). Both professions, now more than a half-century old, assert that they have demonstrated, through practice and research, a commitment to competent, quality health care. In recent years, these assertions have been increasingly centered around acquiring more autonomy and responsibility—what NPs refer to as the ability to practice to the fullest extent of their education and training. As a profession, the NPs have done an excellent job of breaking down unnecessary barriers to their practice.

PAs, however, continue to have challenges with this concept. To address this, a mere three months after my FPA editorial, the House of Delegates of the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) adopted OTP as a policy. The Academy says OTP is designed to increase access to care and help align the PA profession with modern societal health care needs.1

- Allow PAs to practice without a formal agreement with a particular physician

- Create separate majority-PA regulatory boards (or give authority to boards comprised of PAs and physicians who practice with PAs), and

- Allow PAs to be directly reimbursed by all public and private insurers. (PAs continue to be the only health care professionals who bill Medicare but are not entitled to direct reimbursement.)

These changes encourage PAs to practice to the full extent of their training and remove restrictions that currently obstruct delivery of care.1,2 Yet there are unintended consequences as the profession pursues this path.

The Physician Assistant Education Association (PAEA), while supporting most of the OTP policy, has raised concerns about changing curricula to reflect increased autonomy, which would require longer educational programs and incur higher costs for students.3 A significant part of PA education for the past half-century has been the social integration into the health care realm with physicians. There is also concern that changes to accommodate OTP might ultimately lead to a requirement for PAs to have a doctorate degree in order to practice—although not everyone sees that as a drawback!

Proponents of OTP, on the other hand, insist that times have changed and the profession must change with them—or at least, the rules governing the profession must be amended to reflect practical realities. AAPA leaders believe that physician oversight provisions are no longer necessary, and that PAs must acclimate to the changing health care marketplace to solidify the future of the profession and meet the needs of patients.

Continue to: Barriers to PA recruitment continue to...

Barriers to PA recruitment continue to exist as a result of statutory requirements. In today’s health care system, physicians are more likely to be employed by a large institution. Because of this, they may no longer see a financial benefit to entering into a formal agreement with a PA, which is currently required by statute for PAs to practice. Furthermore, as PAs and physicians increasingly practice in groups, the requirement for PAs to have an agreement with a specific physician is challenging to manage and places all providers involved at risk for disciplinary action for administrative infractions unrelated to patient care or outcomes.

Advocates for OTP also emphasize the perception that our NP colleagues are preferentially hired over PAs. In 22 states and the District of Columbia, NPs are allowed to practice without a collaborative agreement with a specific physician, anecdotally making them easier to hire.4 Even in states where NPs do not have FPA, the perception that hiring an NP is less burdensome than hiring a PA often exists. If accurate, these reports suggest PAs are at a disadvantage relative to NPs, resulting in lost opportunities for employment and advancement. (At least one study—based on a survey of members of the American College of Emergency Physicians council, who have direct experience in hiring NPs and PAs—demonstrated no differences in hiring preferences between the two professions. The same survey also revealed wide variability in supervisory requirements, however.5)