User login

CASE New-onset auditory hallucinations

Ms. L, age 78, presents to our hospital with worsening anxiety due to auditory hallucinations. She has been hearing music, which she reports is worse at night and consists of songs, usually the song Jingle Bells, sometimes just melodies and other times with lyrics. Ms. L denies paranoia, visual hallucinations, or worsening mood.

Two weeks ago, Ms. L had visited another hospital, describing 5 days of right-side hearing loss accompanied by pain and burning in her ear and face, along with vesicular lesions in a dermatomal pattern extending into her auditory canal. During this visit, Ms. L’s complete blood count, urine culture, urine drug screen, electrolytes, liver panel, thyroid studies, and vitamin levels were unremarkable. A CT scan of her head showed no abnormalities.

Ms. L was diagnosed with Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), which affects cranial nerves, because of physical examination findings with a dermatomal pattern of lesion distribution and associated pain. Ramsay Hunt syndrome can cause facial paralysis and hearing loss in the affected ear. She was discharged with prescriptions for prednisone 60 mg/d for 7 days and valacyclovir 1 g/d for 7 days and told to follow up with her primary care physician. During the present visit to our hospital, Ms. L’s home health nurse reports that she still has her entire bottles of valacyclovir and prednisone left. Ms. L also has left-side hearing loss that began 5 years ago and a history of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder. Due to the recent onset of right-side hearing loss, her hearing impairment requires her to communicate via writing or via a voice-to-text app.

HISTORY Depressed and living alone

Ms. L was diagnosed with MDD more than 4 decades ago and has been receiving medication since then. She reports no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts, manic symptoms, or psychotic symptoms. For more than 20 years, she has seen a nurse practitioner, who had prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg/d for MDD, poor appetite, and sleep. Within the last 5 years, her nurse practitioner added risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night to augment the mirtazapine for tearfulness, irritability, and mood swings.

Ms. L’s medical history also includes hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She is a retired teacher and lives alone. She has a chore worker who visits her home for 1 hour 5 days a week to help with cleaning and lifting, and support from her son. Ms. L no longer drives and relies on others for transportation, but is able to manage her finances, activities of daily living, cooking, and walking without any assistance.

[polldaddy:12807642]

EVALUATION Identifying the cause of the music

Ms. L is alert and oriented to time and situation, her concentration is appropriate, and her recent and remote memories are preserved. A full cognitive screen is not performed, but she is able to spell WORLD forwards and backwards and adequately perform a serial 7s test. An examination of her ear does not reveal any open vesicular lesions or swelling, but she continues to report pain and tingling in the C7 dermatomal pattern. Her urine drug screen and infectious and autoimmune laboratory testing are unremarkable. She does not have electrolyte, renal function, or blood count abnormalities. An MRI of her brain that is performed to rule out intracranial pathology due to acute hearing loss shows no acute intracranial abnormalities, with some artifact effect due to motion. Because temporal lobe epilepsy can present with hallucinations,1 an EEG is performed to rule out seizure activity; it shows a normal wake pattern.

Psychiatry is consulted for management of the auditory hallucinations because Ms. L is distressed by hearing music. Ms. L is evaluated by Neurology and Otolaryngology. Neurology recommends a repeat brain MRI in the outpatient setting after seeing an artifact in the inpatient imaging, as well as follow-up with her primary care physician. Otolaryngology believes her symptoms are secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome with incomplete treatment, which is consistent with the initial diagnosis from her previous hospital visit, and recommends another course of oral corticosteroids, along with Audiology and Otolaryngology follow-up.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

This is the first case we have seen detailing musical hallucinations (MH) secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome, although musical hallucinations have been associated with other etiologies of hearing loss. MH is a “release phenomenon” believed to be caused by deprivation of stimulation of the auditory cortex.2 They are categorized as complex auditory hallucinations made up of melodies and rhythms and may be present in up to 2.5% of patients with hearing impairment.1 The condition is mostly seen in older adults because this population is more likely to experience hearing loss. MH is more common among women (70% to 80% of cases) and is highly comorbid with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or (as was the case for Ms. L) MDD.3 Hallucinations secondary to hearing loss may be more common in left-side hearing loss.4 In a 2005 study, Warner et al5 found religious music such as hymns or Christmas carols was most commonly heard, possibly due to repetitive past exposure.

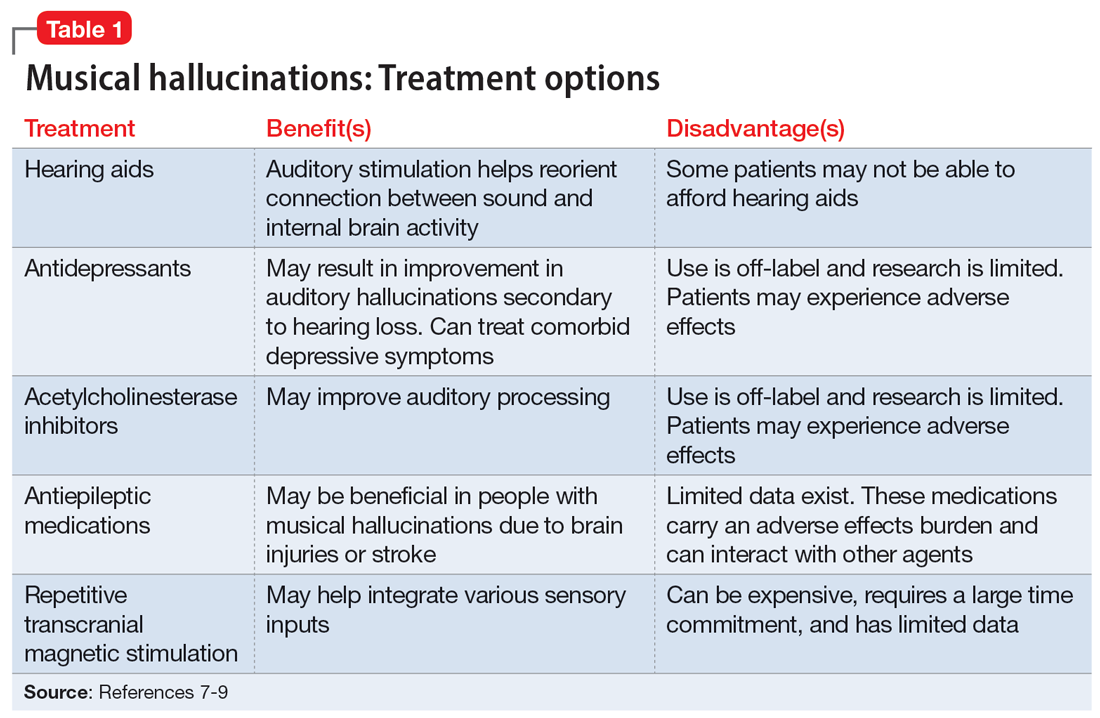

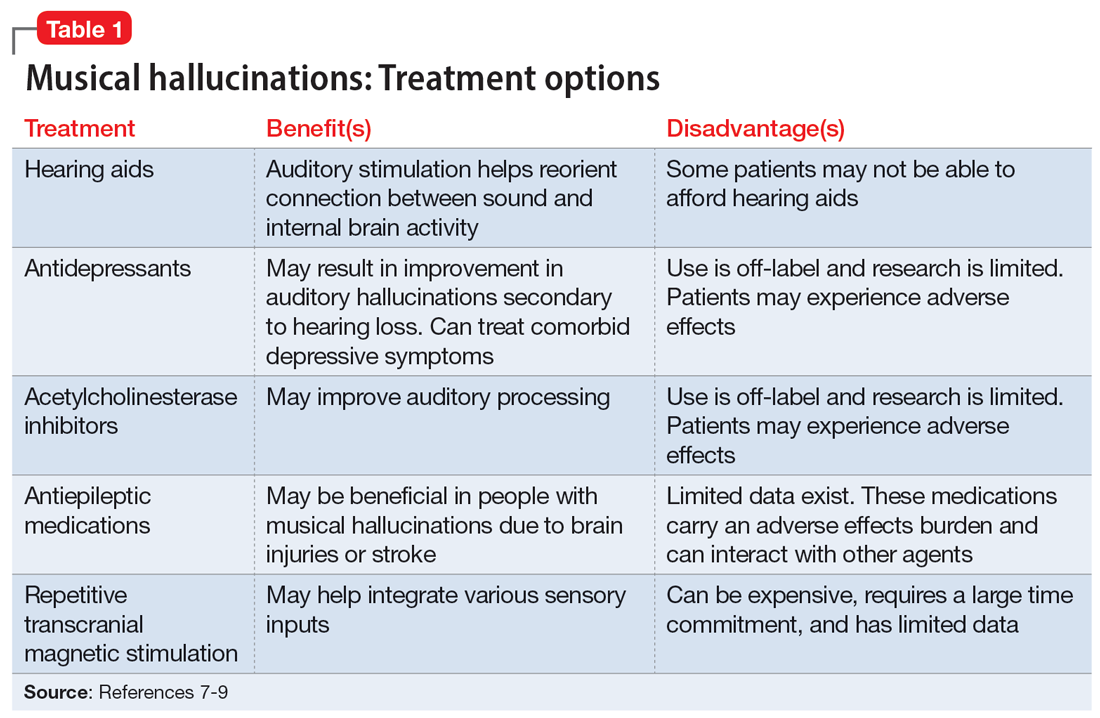

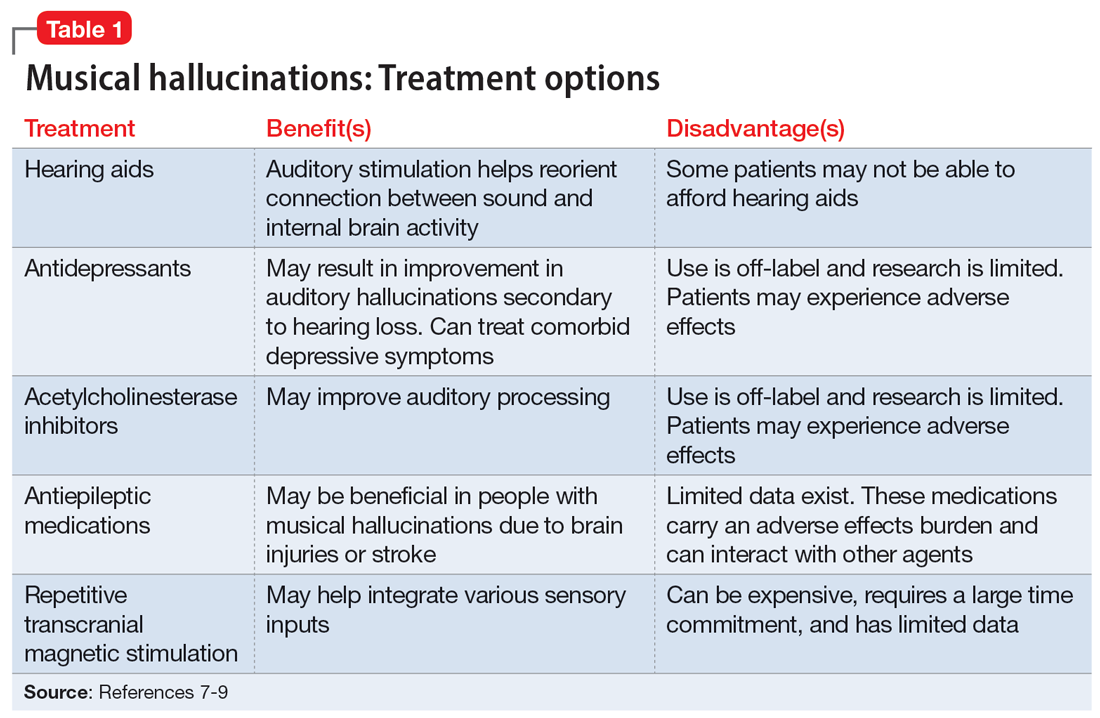

There is no consensus on treatment for MH. Current treatment guidance comes from case reports and case series. Treatment is generally most successful when the etiology of the hallucination is both apparent and treatable, such as an infectious eitiology.3 In the case of MH due to hearing loss, hallucinations may improve following treatment with hearing aids or cochlear implants,1,3,6,7 which is what was advised for Ms. L. Table 17-9 outlines other possible measures for addressing musical hallucinations.

Anticholinesterases, antidepressants, and antiepileptics may provide some benefit.8 However, pharmacotherapy is generally less efficacious and can cause adverse effects, so environmental support and hearing aids may be a safer approach. No medications have been shown to completely cure MH.

TREATMENT Hearing loss management and follow-up

When speaking with the consulting psychiatry team, Ms. L reports her outpatient psychotropic regimen has been helpful. The team decides to continue mirtazapine 30 mg/d and risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night. We recommend that Ms. L discuss tapering off risperidone with her outpatient clinician if they feel it may be indicated to reduce the risk of adverse effects. The treatment team decides not to start corticosteroids due to the risk of steroid-induced psychotic symptoms. The team discusses hallucinations related to hearing loss with Ms. L and advise her to follow up with Audiology and Otolaryngology in the outpatient setting.

The authors’ observations

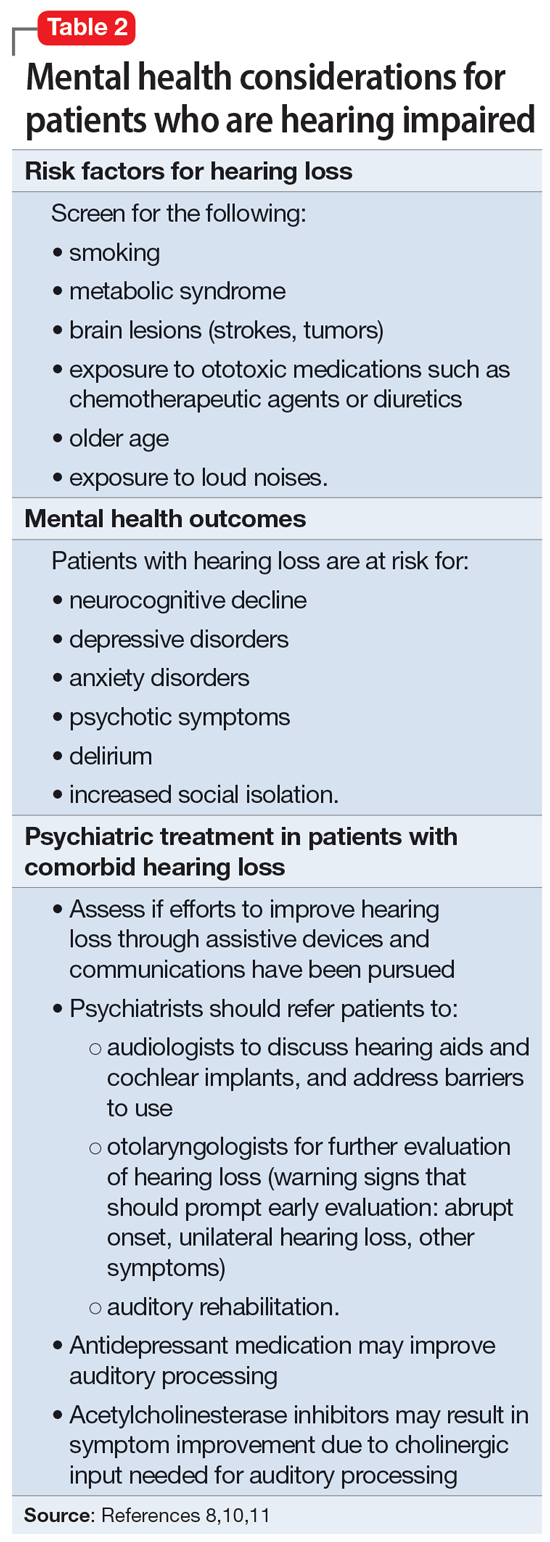

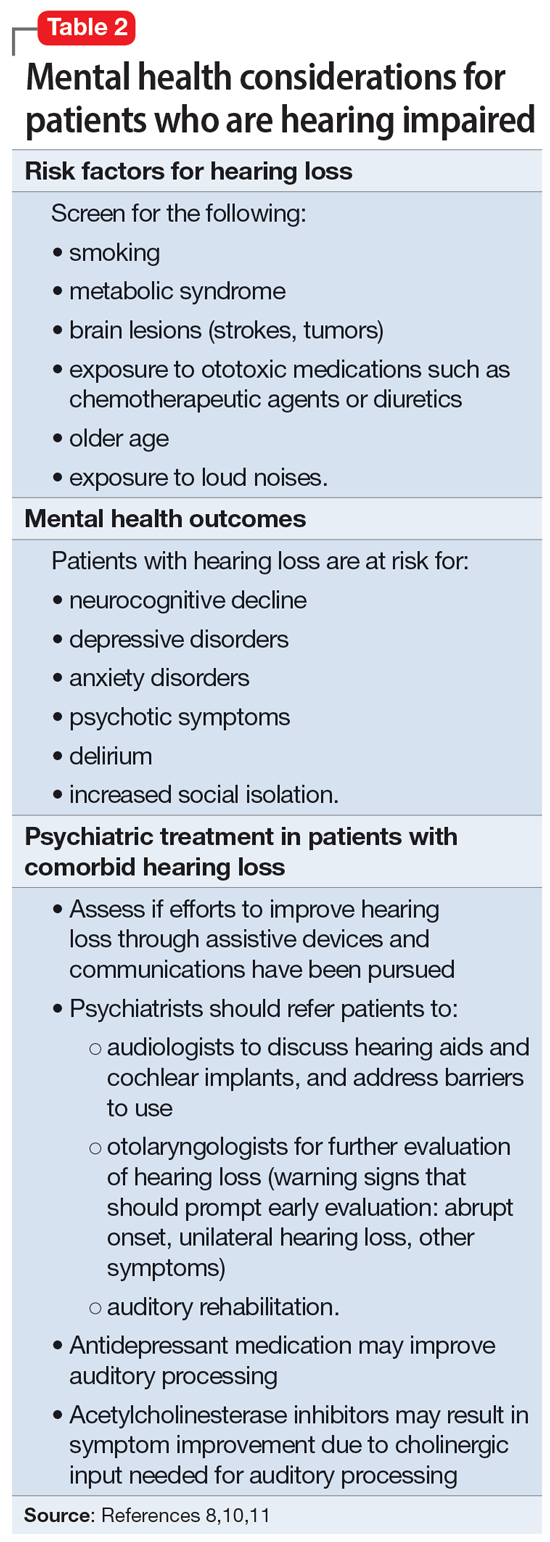

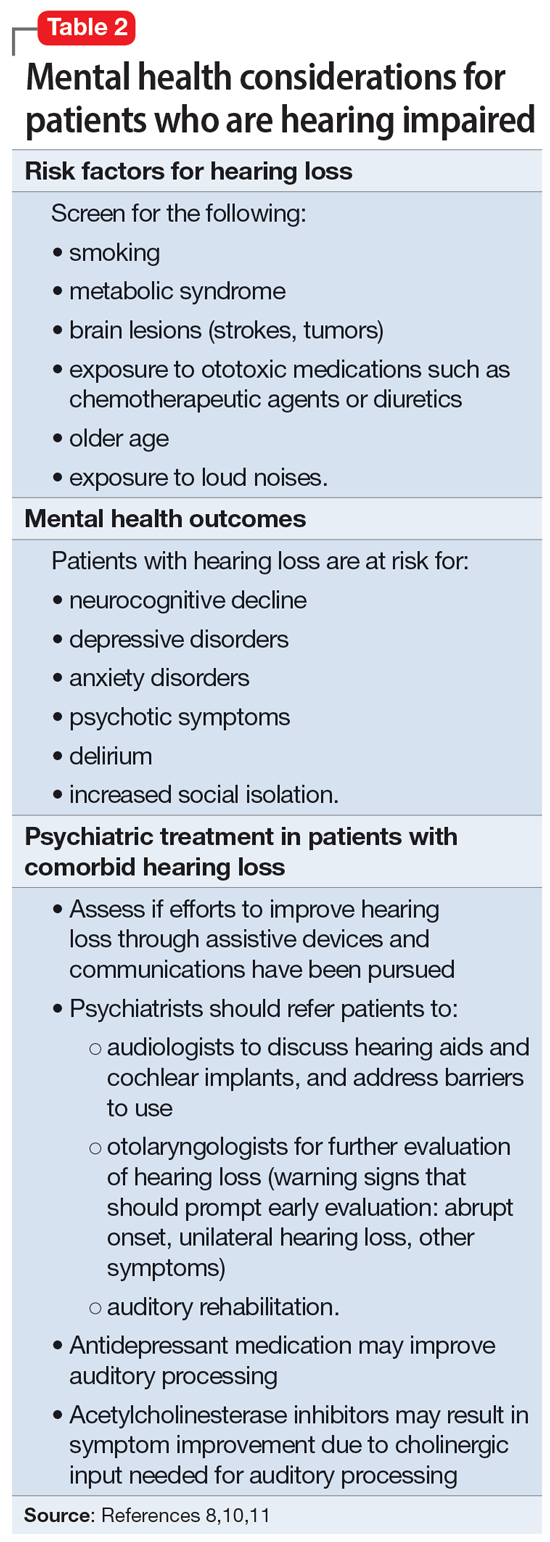

Approximately 40% of people age >60 struggle with hearing impairment4,9; this impacts their general quality of life and how clinicians communicate with such patients.10 People with hearing loss are more likely to develop feelings of social isolation, depression, and delirium (Table 28,10,11).11

Risk factors for hearing loss include tobacco use, metabolic syndrome, exposure to loud noises, and exposure to certain ototoxic medications such as chemotherapeutic agents.11 As psychiatrists, it is important to identify patients who may be at risk for hearing loss and refer them to the appropriate medical professional. If hearing loss is new onset, refer the patient to an otolaryngologist for a full evaluation. Unilateral hearing loss should warrant further workup because this could be due to an acoustic neuroma.11

When providing care for a patient who uses a hearing aid, discuss adherence, barriers to adherence, and difficulties with adjusting the hearing aid. A referral to an audiologist may help patients address these barriers. Patients with hearing impairment or loss may benefit from auditory rehabilitation programs that provide communication strategies, ways to adapt to hearing loss, and information about different assistive options.11 Such programs are often run by audiologists or speech language pathologists and contain both counseling and group components.

Continue to: Is is critical for psychiatrists...

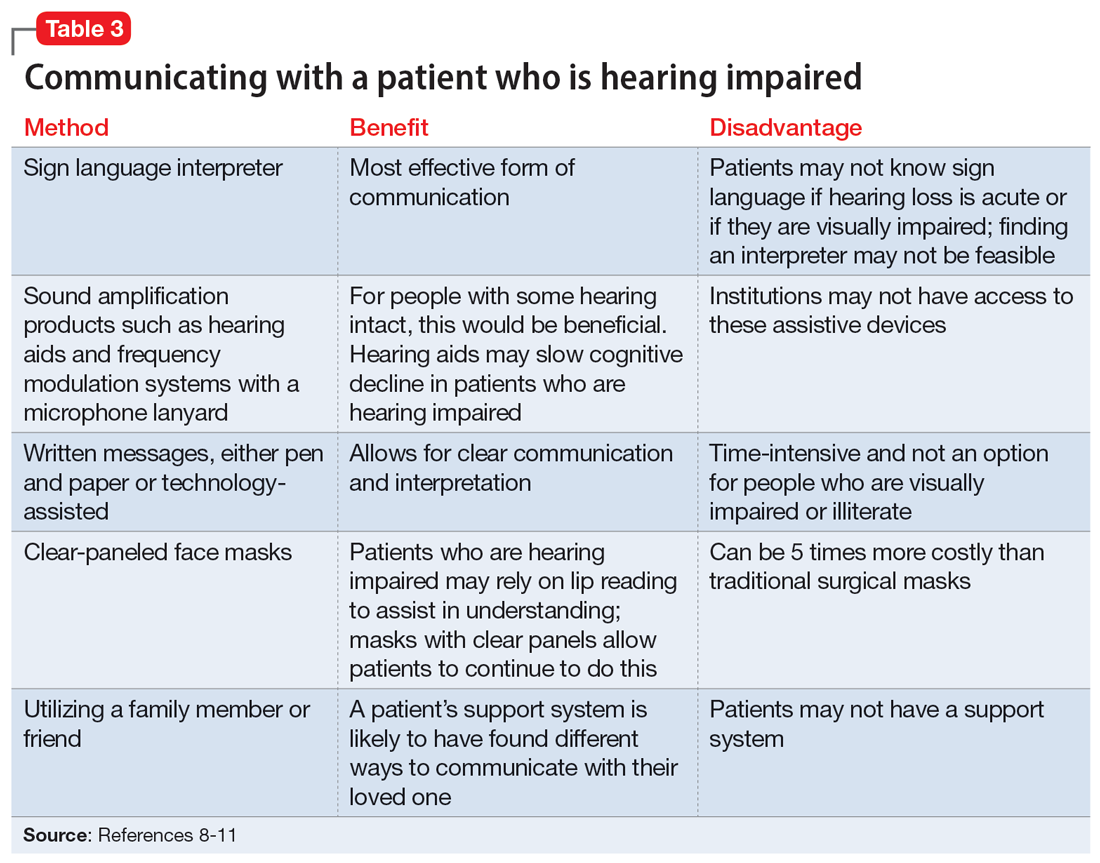

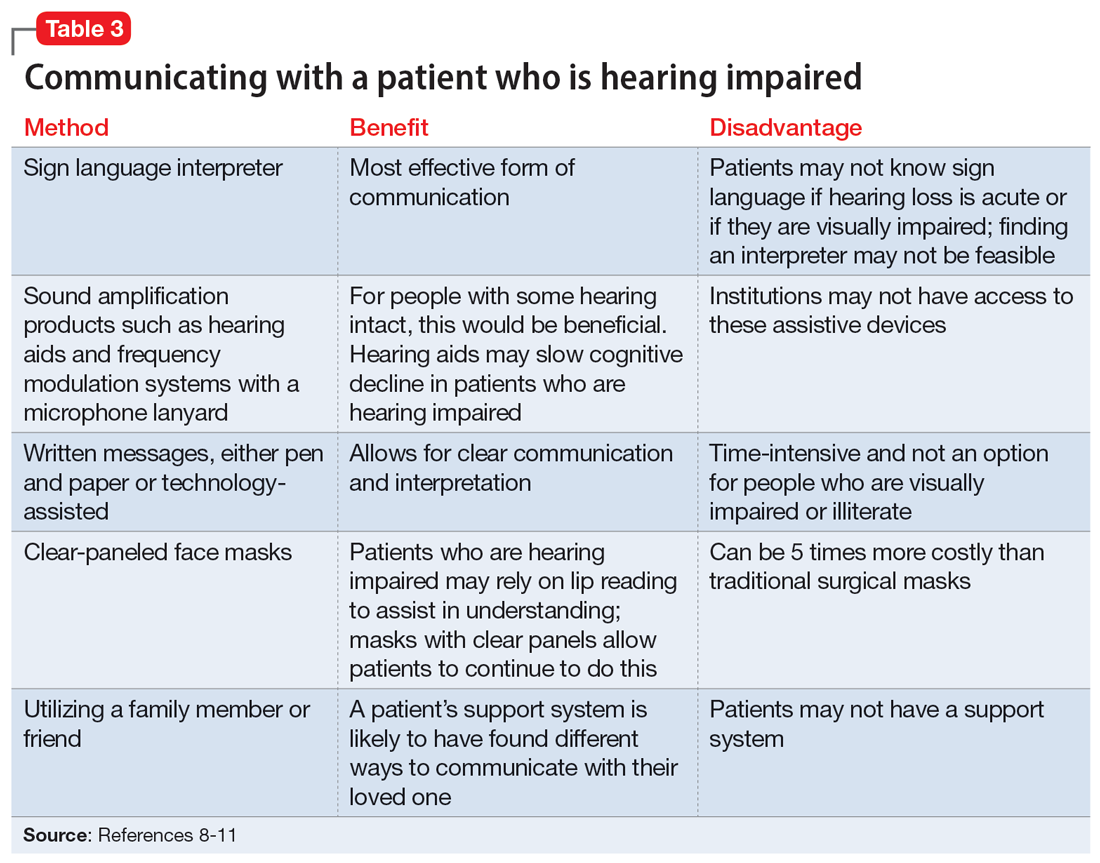

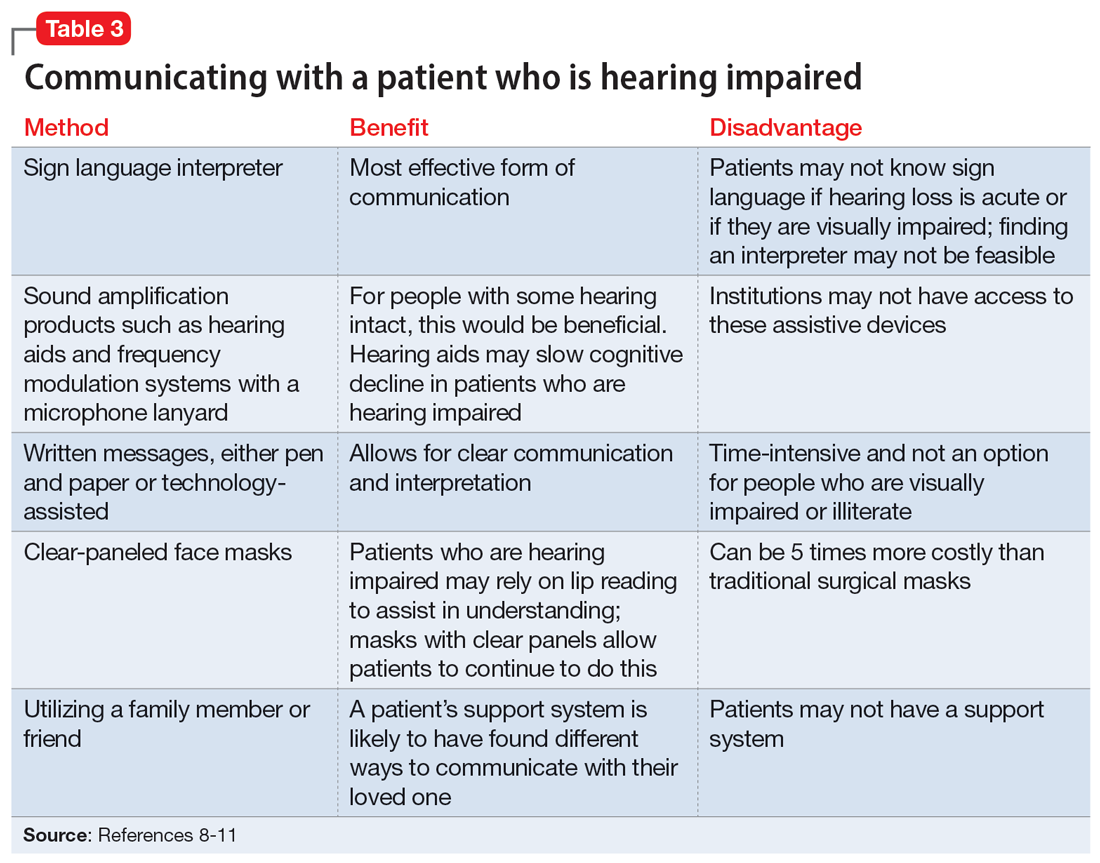

It is critical for psychiatrists to ensure appropriate communication with patients who are hearing impaired (Table 38-11). The use of assistive devices such as sound amplifiers, written messages, or family members to assist in communication is needed to prevent miscommunication.9-11

OUTCOME Lack of follow-up

A home health worker visits Ms. L, communicating with her using voice-to-text. Ms. L has not yet gone to her primary care physician, audiologist, or outpatient psychiatrist for follow-up because she needs to arrange transportation. Ms. L remains distressed by the music she is hearing, which is worse at night, along with her acute hearing loss.

Bottom Line

Hearing loss can predispose a person to psychiatric disorders and symptoms, including depression, delirium, and auditory hallucinations. Psychiatrists should strive to ensure clear communication with patients who are hearing impaired and should refer such patients to appropriate resources to improve outcomes.

Related Resources

- Wang J, Patel D, Francois D. Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):46-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0091

- Sosland MD, Pinninti N. 5 ways to quiet auditory hallucinations. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(4):110.

- Convery E, Keidser G, McLelland M, et al. A smartphone app to facilitate remote patient-provider communication in hearing health care: usability and effect on hearing aid outcomes. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(6):798-804. doi:10.1089/ tmj.2019.0109

Drug Brand Names

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Prednisone • Rayos

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valacyclovir • Valtrex

1. Cole MG, Dowson L, Dendukuri N, et al. The prevalence and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations among elderly subjects attending an audiology clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(5):444-452. doi:10.1002/gps.618

2. Alvarez Perez P, Garcia-Antelo MJ, Rubio-Nazabal E. “Doctor, I hear music”: a brief review about musical hallucinations. Open Neurol J. 2017;11:11-14. doi:10.2174/1874205X01711010011

3. Sanchez TG, Rocha SCM, Knobel KAB, et al. Musical hallucination associated with hearing loss. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69(2B):395-400. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2011000300024

4. Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MGM. Prevalence of musical hallucinations in patients referred for audiometric testing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(12):1075-1077. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823e31c4

5. Warner N, Aziz V. Hymns and arias: musical hallucinations in older people in Wales. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(7):658-660. doi:10.1002/gps.1338

6. Low WK, Tham CA, D’Souza VD, et al. Musical ear syndrome in adult cochlear implant patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(9):854-858. doi:10.1017/S0022215113001758

7. Brunner JP, Amedee RG. Musical hallucinations in a patient with presbycusis: a case report. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):89-91.

8. Coebergh JAF, Lauw RF, Bots R, et al. Musical hallucinations: review of treatment effects. Front Psychol. 2015;6:814. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00814

9. Ten Hulzen RD, Fabry DA. Impact of hearing loss and universal face masking in the COVID-19 era. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2069-2072. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.027

10. Shukla A, Nieman CL, Price C, et al. Impact of hearing loss on patient-provider communication among hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Am J Med Qual. 2019;34(3):284-292. doi:10.1177/1062860618798926

11. Blazer DG, Tucci DL. Hearing loss and psychiatric disorders: a review. Psychol Med. 2019;49(6):891-897. doi:10.1017/S0033291718003409

CASE New-onset auditory hallucinations

Ms. L, age 78, presents to our hospital with worsening anxiety due to auditory hallucinations. She has been hearing music, which she reports is worse at night and consists of songs, usually the song Jingle Bells, sometimes just melodies and other times with lyrics. Ms. L denies paranoia, visual hallucinations, or worsening mood.

Two weeks ago, Ms. L had visited another hospital, describing 5 days of right-side hearing loss accompanied by pain and burning in her ear and face, along with vesicular lesions in a dermatomal pattern extending into her auditory canal. During this visit, Ms. L’s complete blood count, urine culture, urine drug screen, electrolytes, liver panel, thyroid studies, and vitamin levels were unremarkable. A CT scan of her head showed no abnormalities.

Ms. L was diagnosed with Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), which affects cranial nerves, because of physical examination findings with a dermatomal pattern of lesion distribution and associated pain. Ramsay Hunt syndrome can cause facial paralysis and hearing loss in the affected ear. She was discharged with prescriptions for prednisone 60 mg/d for 7 days and valacyclovir 1 g/d for 7 days and told to follow up with her primary care physician. During the present visit to our hospital, Ms. L’s home health nurse reports that she still has her entire bottles of valacyclovir and prednisone left. Ms. L also has left-side hearing loss that began 5 years ago and a history of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder. Due to the recent onset of right-side hearing loss, her hearing impairment requires her to communicate via writing or via a voice-to-text app.

HISTORY Depressed and living alone

Ms. L was diagnosed with MDD more than 4 decades ago and has been receiving medication since then. She reports no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts, manic symptoms, or psychotic symptoms. For more than 20 years, she has seen a nurse practitioner, who had prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg/d for MDD, poor appetite, and sleep. Within the last 5 years, her nurse practitioner added risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night to augment the mirtazapine for tearfulness, irritability, and mood swings.

Ms. L’s medical history also includes hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She is a retired teacher and lives alone. She has a chore worker who visits her home for 1 hour 5 days a week to help with cleaning and lifting, and support from her son. Ms. L no longer drives and relies on others for transportation, but is able to manage her finances, activities of daily living, cooking, and walking without any assistance.

[polldaddy:12807642]

EVALUATION Identifying the cause of the music

Ms. L is alert and oriented to time and situation, her concentration is appropriate, and her recent and remote memories are preserved. A full cognitive screen is not performed, but she is able to spell WORLD forwards and backwards and adequately perform a serial 7s test. An examination of her ear does not reveal any open vesicular lesions or swelling, but she continues to report pain and tingling in the C7 dermatomal pattern. Her urine drug screen and infectious and autoimmune laboratory testing are unremarkable. She does not have electrolyte, renal function, or blood count abnormalities. An MRI of her brain that is performed to rule out intracranial pathology due to acute hearing loss shows no acute intracranial abnormalities, with some artifact effect due to motion. Because temporal lobe epilepsy can present with hallucinations,1 an EEG is performed to rule out seizure activity; it shows a normal wake pattern.

Psychiatry is consulted for management of the auditory hallucinations because Ms. L is distressed by hearing music. Ms. L is evaluated by Neurology and Otolaryngology. Neurology recommends a repeat brain MRI in the outpatient setting after seeing an artifact in the inpatient imaging, as well as follow-up with her primary care physician. Otolaryngology believes her symptoms are secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome with incomplete treatment, which is consistent with the initial diagnosis from her previous hospital visit, and recommends another course of oral corticosteroids, along with Audiology and Otolaryngology follow-up.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

This is the first case we have seen detailing musical hallucinations (MH) secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome, although musical hallucinations have been associated with other etiologies of hearing loss. MH is a “release phenomenon” believed to be caused by deprivation of stimulation of the auditory cortex.2 They are categorized as complex auditory hallucinations made up of melodies and rhythms and may be present in up to 2.5% of patients with hearing impairment.1 The condition is mostly seen in older adults because this population is more likely to experience hearing loss. MH is more common among women (70% to 80% of cases) and is highly comorbid with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or (as was the case for Ms. L) MDD.3 Hallucinations secondary to hearing loss may be more common in left-side hearing loss.4 In a 2005 study, Warner et al5 found religious music such as hymns or Christmas carols was most commonly heard, possibly due to repetitive past exposure.

There is no consensus on treatment for MH. Current treatment guidance comes from case reports and case series. Treatment is generally most successful when the etiology of the hallucination is both apparent and treatable, such as an infectious eitiology.3 In the case of MH due to hearing loss, hallucinations may improve following treatment with hearing aids or cochlear implants,1,3,6,7 which is what was advised for Ms. L. Table 17-9 outlines other possible measures for addressing musical hallucinations.

Anticholinesterases, antidepressants, and antiepileptics may provide some benefit.8 However, pharmacotherapy is generally less efficacious and can cause adverse effects, so environmental support and hearing aids may be a safer approach. No medications have been shown to completely cure MH.

TREATMENT Hearing loss management and follow-up

When speaking with the consulting psychiatry team, Ms. L reports her outpatient psychotropic regimen has been helpful. The team decides to continue mirtazapine 30 mg/d and risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night. We recommend that Ms. L discuss tapering off risperidone with her outpatient clinician if they feel it may be indicated to reduce the risk of adverse effects. The treatment team decides not to start corticosteroids due to the risk of steroid-induced psychotic symptoms. The team discusses hallucinations related to hearing loss with Ms. L and advise her to follow up with Audiology and Otolaryngology in the outpatient setting.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 40% of people age >60 struggle with hearing impairment4,9; this impacts their general quality of life and how clinicians communicate with such patients.10 People with hearing loss are more likely to develop feelings of social isolation, depression, and delirium (Table 28,10,11).11

Risk factors for hearing loss include tobacco use, metabolic syndrome, exposure to loud noises, and exposure to certain ototoxic medications such as chemotherapeutic agents.11 As psychiatrists, it is important to identify patients who may be at risk for hearing loss and refer them to the appropriate medical professional. If hearing loss is new onset, refer the patient to an otolaryngologist for a full evaluation. Unilateral hearing loss should warrant further workup because this could be due to an acoustic neuroma.11

When providing care for a patient who uses a hearing aid, discuss adherence, barriers to adherence, and difficulties with adjusting the hearing aid. A referral to an audiologist may help patients address these barriers. Patients with hearing impairment or loss may benefit from auditory rehabilitation programs that provide communication strategies, ways to adapt to hearing loss, and information about different assistive options.11 Such programs are often run by audiologists or speech language pathologists and contain both counseling and group components.

Continue to: Is is critical for psychiatrists...

It is critical for psychiatrists to ensure appropriate communication with patients who are hearing impaired (Table 38-11). The use of assistive devices such as sound amplifiers, written messages, or family members to assist in communication is needed to prevent miscommunication.9-11

OUTCOME Lack of follow-up

A home health worker visits Ms. L, communicating with her using voice-to-text. Ms. L has not yet gone to her primary care physician, audiologist, or outpatient psychiatrist for follow-up because she needs to arrange transportation. Ms. L remains distressed by the music she is hearing, which is worse at night, along with her acute hearing loss.

Bottom Line

Hearing loss can predispose a person to psychiatric disorders and symptoms, including depression, delirium, and auditory hallucinations. Psychiatrists should strive to ensure clear communication with patients who are hearing impaired and should refer such patients to appropriate resources to improve outcomes.

Related Resources

- Wang J, Patel D, Francois D. Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):46-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0091

- Sosland MD, Pinninti N. 5 ways to quiet auditory hallucinations. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(4):110.

- Convery E, Keidser G, McLelland M, et al. A smartphone app to facilitate remote patient-provider communication in hearing health care: usability and effect on hearing aid outcomes. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(6):798-804. doi:10.1089/ tmj.2019.0109

Drug Brand Names

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Prednisone • Rayos

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valacyclovir • Valtrex

CASE New-onset auditory hallucinations

Ms. L, age 78, presents to our hospital with worsening anxiety due to auditory hallucinations. She has been hearing music, which she reports is worse at night and consists of songs, usually the song Jingle Bells, sometimes just melodies and other times with lyrics. Ms. L denies paranoia, visual hallucinations, or worsening mood.

Two weeks ago, Ms. L had visited another hospital, describing 5 days of right-side hearing loss accompanied by pain and burning in her ear and face, along with vesicular lesions in a dermatomal pattern extending into her auditory canal. During this visit, Ms. L’s complete blood count, urine culture, urine drug screen, electrolytes, liver panel, thyroid studies, and vitamin levels were unremarkable. A CT scan of her head showed no abnormalities.

Ms. L was diagnosed with Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), which affects cranial nerves, because of physical examination findings with a dermatomal pattern of lesion distribution and associated pain. Ramsay Hunt syndrome can cause facial paralysis and hearing loss in the affected ear. She was discharged with prescriptions for prednisone 60 mg/d for 7 days and valacyclovir 1 g/d for 7 days and told to follow up with her primary care physician. During the present visit to our hospital, Ms. L’s home health nurse reports that she still has her entire bottles of valacyclovir and prednisone left. Ms. L also has left-side hearing loss that began 5 years ago and a history of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder. Due to the recent onset of right-side hearing loss, her hearing impairment requires her to communicate via writing or via a voice-to-text app.

HISTORY Depressed and living alone

Ms. L was diagnosed with MDD more than 4 decades ago and has been receiving medication since then. She reports no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts, manic symptoms, or psychotic symptoms. For more than 20 years, she has seen a nurse practitioner, who had prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg/d for MDD, poor appetite, and sleep. Within the last 5 years, her nurse practitioner added risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night to augment the mirtazapine for tearfulness, irritability, and mood swings.

Ms. L’s medical history also includes hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She is a retired teacher and lives alone. She has a chore worker who visits her home for 1 hour 5 days a week to help with cleaning and lifting, and support from her son. Ms. L no longer drives and relies on others for transportation, but is able to manage her finances, activities of daily living, cooking, and walking without any assistance.

[polldaddy:12807642]

EVALUATION Identifying the cause of the music

Ms. L is alert and oriented to time and situation, her concentration is appropriate, and her recent and remote memories are preserved. A full cognitive screen is not performed, but she is able to spell WORLD forwards and backwards and adequately perform a serial 7s test. An examination of her ear does not reveal any open vesicular lesions or swelling, but she continues to report pain and tingling in the C7 dermatomal pattern. Her urine drug screen and infectious and autoimmune laboratory testing are unremarkable. She does not have electrolyte, renal function, or blood count abnormalities. An MRI of her brain that is performed to rule out intracranial pathology due to acute hearing loss shows no acute intracranial abnormalities, with some artifact effect due to motion. Because temporal lobe epilepsy can present with hallucinations,1 an EEG is performed to rule out seizure activity; it shows a normal wake pattern.

Psychiatry is consulted for management of the auditory hallucinations because Ms. L is distressed by hearing music. Ms. L is evaluated by Neurology and Otolaryngology. Neurology recommends a repeat brain MRI in the outpatient setting after seeing an artifact in the inpatient imaging, as well as follow-up with her primary care physician. Otolaryngology believes her symptoms are secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome with incomplete treatment, which is consistent with the initial diagnosis from her previous hospital visit, and recommends another course of oral corticosteroids, along with Audiology and Otolaryngology follow-up.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

This is the first case we have seen detailing musical hallucinations (MH) secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome, although musical hallucinations have been associated with other etiologies of hearing loss. MH is a “release phenomenon” believed to be caused by deprivation of stimulation of the auditory cortex.2 They are categorized as complex auditory hallucinations made up of melodies and rhythms and may be present in up to 2.5% of patients with hearing impairment.1 The condition is mostly seen in older adults because this population is more likely to experience hearing loss. MH is more common among women (70% to 80% of cases) and is highly comorbid with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or (as was the case for Ms. L) MDD.3 Hallucinations secondary to hearing loss may be more common in left-side hearing loss.4 In a 2005 study, Warner et al5 found religious music such as hymns or Christmas carols was most commonly heard, possibly due to repetitive past exposure.

There is no consensus on treatment for MH. Current treatment guidance comes from case reports and case series. Treatment is generally most successful when the etiology of the hallucination is both apparent and treatable, such as an infectious eitiology.3 In the case of MH due to hearing loss, hallucinations may improve following treatment with hearing aids or cochlear implants,1,3,6,7 which is what was advised for Ms. L. Table 17-9 outlines other possible measures for addressing musical hallucinations.

Anticholinesterases, antidepressants, and antiepileptics may provide some benefit.8 However, pharmacotherapy is generally less efficacious and can cause adverse effects, so environmental support and hearing aids may be a safer approach. No medications have been shown to completely cure MH.

TREATMENT Hearing loss management and follow-up

When speaking with the consulting psychiatry team, Ms. L reports her outpatient psychotropic regimen has been helpful. The team decides to continue mirtazapine 30 mg/d and risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night. We recommend that Ms. L discuss tapering off risperidone with her outpatient clinician if they feel it may be indicated to reduce the risk of adverse effects. The treatment team decides not to start corticosteroids due to the risk of steroid-induced psychotic symptoms. The team discusses hallucinations related to hearing loss with Ms. L and advise her to follow up with Audiology and Otolaryngology in the outpatient setting.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 40% of people age >60 struggle with hearing impairment4,9; this impacts their general quality of life and how clinicians communicate with such patients.10 People with hearing loss are more likely to develop feelings of social isolation, depression, and delirium (Table 28,10,11).11

Risk factors for hearing loss include tobacco use, metabolic syndrome, exposure to loud noises, and exposure to certain ototoxic medications such as chemotherapeutic agents.11 As psychiatrists, it is important to identify patients who may be at risk for hearing loss and refer them to the appropriate medical professional. If hearing loss is new onset, refer the patient to an otolaryngologist for a full evaluation. Unilateral hearing loss should warrant further workup because this could be due to an acoustic neuroma.11

When providing care for a patient who uses a hearing aid, discuss adherence, barriers to adherence, and difficulties with adjusting the hearing aid. A referral to an audiologist may help patients address these barriers. Patients with hearing impairment or loss may benefit from auditory rehabilitation programs that provide communication strategies, ways to adapt to hearing loss, and information about different assistive options.11 Such programs are often run by audiologists or speech language pathologists and contain both counseling and group components.

Continue to: Is is critical for psychiatrists...

It is critical for psychiatrists to ensure appropriate communication with patients who are hearing impaired (Table 38-11). The use of assistive devices such as sound amplifiers, written messages, or family members to assist in communication is needed to prevent miscommunication.9-11

OUTCOME Lack of follow-up

A home health worker visits Ms. L, communicating with her using voice-to-text. Ms. L has not yet gone to her primary care physician, audiologist, or outpatient psychiatrist for follow-up because she needs to arrange transportation. Ms. L remains distressed by the music she is hearing, which is worse at night, along with her acute hearing loss.

Bottom Line

Hearing loss can predispose a person to psychiatric disorders and symptoms, including depression, delirium, and auditory hallucinations. Psychiatrists should strive to ensure clear communication with patients who are hearing impaired and should refer such patients to appropriate resources to improve outcomes.

Related Resources

- Wang J, Patel D, Francois D. Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):46-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0091

- Sosland MD, Pinninti N. 5 ways to quiet auditory hallucinations. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(4):110.

- Convery E, Keidser G, McLelland M, et al. A smartphone app to facilitate remote patient-provider communication in hearing health care: usability and effect on hearing aid outcomes. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(6):798-804. doi:10.1089/ tmj.2019.0109

Drug Brand Names

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Prednisone • Rayos

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valacyclovir • Valtrex

1. Cole MG, Dowson L, Dendukuri N, et al. The prevalence and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations among elderly subjects attending an audiology clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(5):444-452. doi:10.1002/gps.618

2. Alvarez Perez P, Garcia-Antelo MJ, Rubio-Nazabal E. “Doctor, I hear music”: a brief review about musical hallucinations. Open Neurol J. 2017;11:11-14. doi:10.2174/1874205X01711010011

3. Sanchez TG, Rocha SCM, Knobel KAB, et al. Musical hallucination associated with hearing loss. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69(2B):395-400. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2011000300024

4. Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MGM. Prevalence of musical hallucinations in patients referred for audiometric testing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(12):1075-1077. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823e31c4

5. Warner N, Aziz V. Hymns and arias: musical hallucinations in older people in Wales. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(7):658-660. doi:10.1002/gps.1338

6. Low WK, Tham CA, D’Souza VD, et al. Musical ear syndrome in adult cochlear implant patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(9):854-858. doi:10.1017/S0022215113001758

7. Brunner JP, Amedee RG. Musical hallucinations in a patient with presbycusis: a case report. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):89-91.

8. Coebergh JAF, Lauw RF, Bots R, et al. Musical hallucinations: review of treatment effects. Front Psychol. 2015;6:814. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00814

9. Ten Hulzen RD, Fabry DA. Impact of hearing loss and universal face masking in the COVID-19 era. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2069-2072. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.027

10. Shukla A, Nieman CL, Price C, et al. Impact of hearing loss on patient-provider communication among hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Am J Med Qual. 2019;34(3):284-292. doi:10.1177/1062860618798926

11. Blazer DG, Tucci DL. Hearing loss and psychiatric disorders: a review. Psychol Med. 2019;49(6):891-897. doi:10.1017/S0033291718003409

1. Cole MG, Dowson L, Dendukuri N, et al. The prevalence and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations among elderly subjects attending an audiology clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(5):444-452. doi:10.1002/gps.618

2. Alvarez Perez P, Garcia-Antelo MJ, Rubio-Nazabal E. “Doctor, I hear music”: a brief review about musical hallucinations. Open Neurol J. 2017;11:11-14. doi:10.2174/1874205X01711010011

3. Sanchez TG, Rocha SCM, Knobel KAB, et al. Musical hallucination associated with hearing loss. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69(2B):395-400. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2011000300024

4. Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MGM. Prevalence of musical hallucinations in patients referred for audiometric testing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(12):1075-1077. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823e31c4

5. Warner N, Aziz V. Hymns and arias: musical hallucinations in older people in Wales. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(7):658-660. doi:10.1002/gps.1338

6. Low WK, Tham CA, D’Souza VD, et al. Musical ear syndrome in adult cochlear implant patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(9):854-858. doi:10.1017/S0022215113001758

7. Brunner JP, Amedee RG. Musical hallucinations in a patient with presbycusis: a case report. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):89-91.

8. Coebergh JAF, Lauw RF, Bots R, et al. Musical hallucinations: review of treatment effects. Front Psychol. 2015;6:814. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00814

9. Ten Hulzen RD, Fabry DA. Impact of hearing loss and universal face masking in the COVID-19 era. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2069-2072. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.027

10. Shukla A, Nieman CL, Price C, et al. Impact of hearing loss on patient-provider communication among hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Am J Med Qual. 2019;34(3):284-292. doi:10.1177/1062860618798926

11. Blazer DG, Tucci DL. Hearing loss and psychiatric disorders: a review. Psychol Med. 2019;49(6):891-897. doi:10.1017/S0033291718003409