User login

Auditory hallucinations in a patient who is hearing impaired

CASE New-onset auditory hallucinations

Ms. L, age 78, presents to our hospital with worsening anxiety due to auditory hallucinations. She has been hearing music, which she reports is worse at night and consists of songs, usually the song Jingle Bells, sometimes just melodies and other times with lyrics. Ms. L denies paranoia, visual hallucinations, or worsening mood.

Two weeks ago, Ms. L had visited another hospital, describing 5 days of right-side hearing loss accompanied by pain and burning in her ear and face, along with vesicular lesions in a dermatomal pattern extending into her auditory canal. During this visit, Ms. L’s complete blood count, urine culture, urine drug screen, electrolytes, liver panel, thyroid studies, and vitamin levels were unremarkable. A CT scan of her head showed no abnormalities.

Ms. L was diagnosed with Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), which affects cranial nerves, because of physical examination findings with a dermatomal pattern of lesion distribution and associated pain. Ramsay Hunt syndrome can cause facial paralysis and hearing loss in the affected ear. She was discharged with prescriptions for prednisone 60 mg/d for 7 days and valacyclovir 1 g/d for 7 days and told to follow up with her primary care physician. During the present visit to our hospital, Ms. L’s home health nurse reports that she still has her entire bottles of valacyclovir and prednisone left. Ms. L also has left-side hearing loss that began 5 years ago and a history of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder. Due to the recent onset of right-side hearing loss, her hearing impairment requires her to communicate via writing or via a voice-to-text app.

HISTORY Depressed and living alone

Ms. L was diagnosed with MDD more than 4 decades ago and has been receiving medication since then. She reports no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts, manic symptoms, or psychotic symptoms. For more than 20 years, she has seen a nurse practitioner, who had prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg/d for MDD, poor appetite, and sleep. Within the last 5 years, her nurse practitioner added risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night to augment the mirtazapine for tearfulness, irritability, and mood swings.

Ms. L’s medical history also includes hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She is a retired teacher and lives alone. She has a chore worker who visits her home for 1 hour 5 days a week to help with cleaning and lifting, and support from her son. Ms. L no longer drives and relies on others for transportation, but is able to manage her finances, activities of daily living, cooking, and walking without any assistance.

[polldaddy:12807642]

EVALUATION Identifying the cause of the music

Ms. L is alert and oriented to time and situation, her concentration is appropriate, and her recent and remote memories are preserved. A full cognitive screen is not performed, but she is able to spell WORLD forwards and backwards and adequately perform a serial 7s test. An examination of her ear does not reveal any open vesicular lesions or swelling, but she continues to report pain and tingling in the C7 dermatomal pattern. Her urine drug screen and infectious and autoimmune laboratory testing are unremarkable. She does not have electrolyte, renal function, or blood count abnormalities. An MRI of her brain that is performed to rule out intracranial pathology due to acute hearing loss shows no acute intracranial abnormalities, with some artifact effect due to motion. Because temporal lobe epilepsy can present with hallucinations,1 an EEG is performed to rule out seizure activity; it shows a normal wake pattern.

Psychiatry is consulted for management of the auditory hallucinations because Ms. L is distressed by hearing music. Ms. L is evaluated by Neurology and Otolaryngology. Neurology recommends a repeat brain MRI in the outpatient setting after seeing an artifact in the inpatient imaging, as well as follow-up with her primary care physician. Otolaryngology believes her symptoms are secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome with incomplete treatment, which is consistent with the initial diagnosis from her previous hospital visit, and recommends another course of oral corticosteroids, along with Audiology and Otolaryngology follow-up.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

This is the first case we have seen detailing musical hallucinations (MH) secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome, although musical hallucinations have been associated with other etiologies of hearing loss. MH is a “release phenomenon” believed to be caused by deprivation of stimulation of the auditory cortex.2 They are categorized as complex auditory hallucinations made up of melodies and rhythms and may be present in up to 2.5% of patients with hearing impairment.1 The condition is mostly seen in older adults because this population is more likely to experience hearing loss. MH is more common among women (70% to 80% of cases) and is highly comorbid with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or (as was the case for Ms. L) MDD.3 Hallucinations secondary to hearing loss may be more common in left-side hearing loss.4 In a 2005 study, Warner et al5 found religious music such as hymns or Christmas carols was most commonly heard, possibly due to repetitive past exposure.

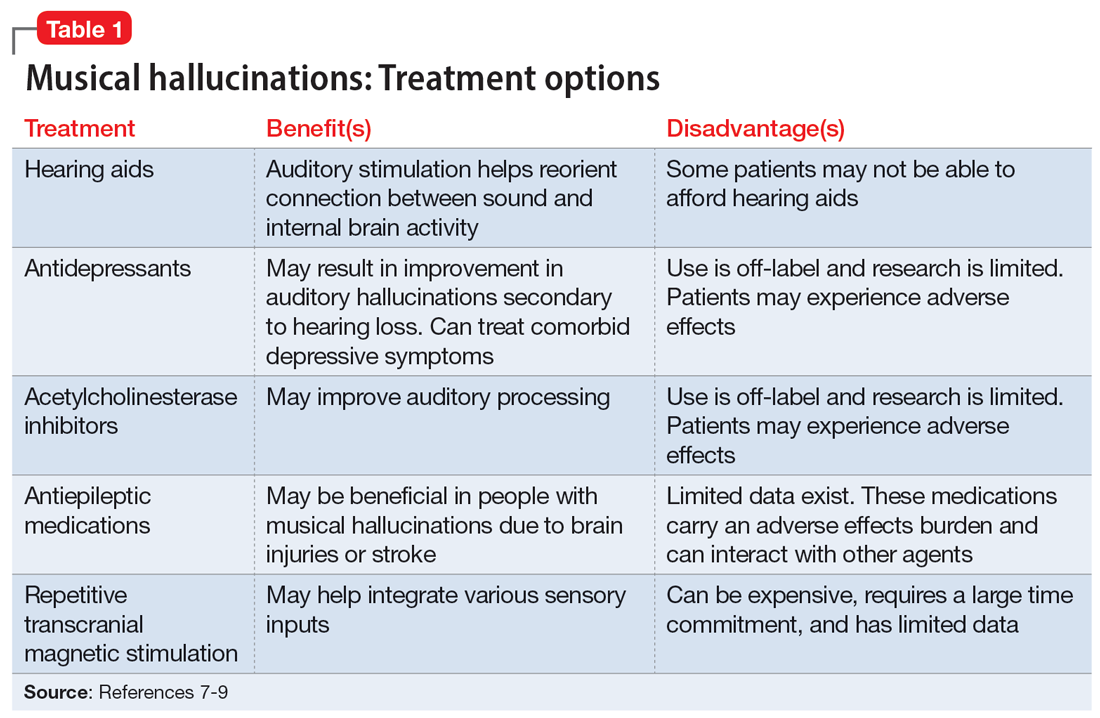

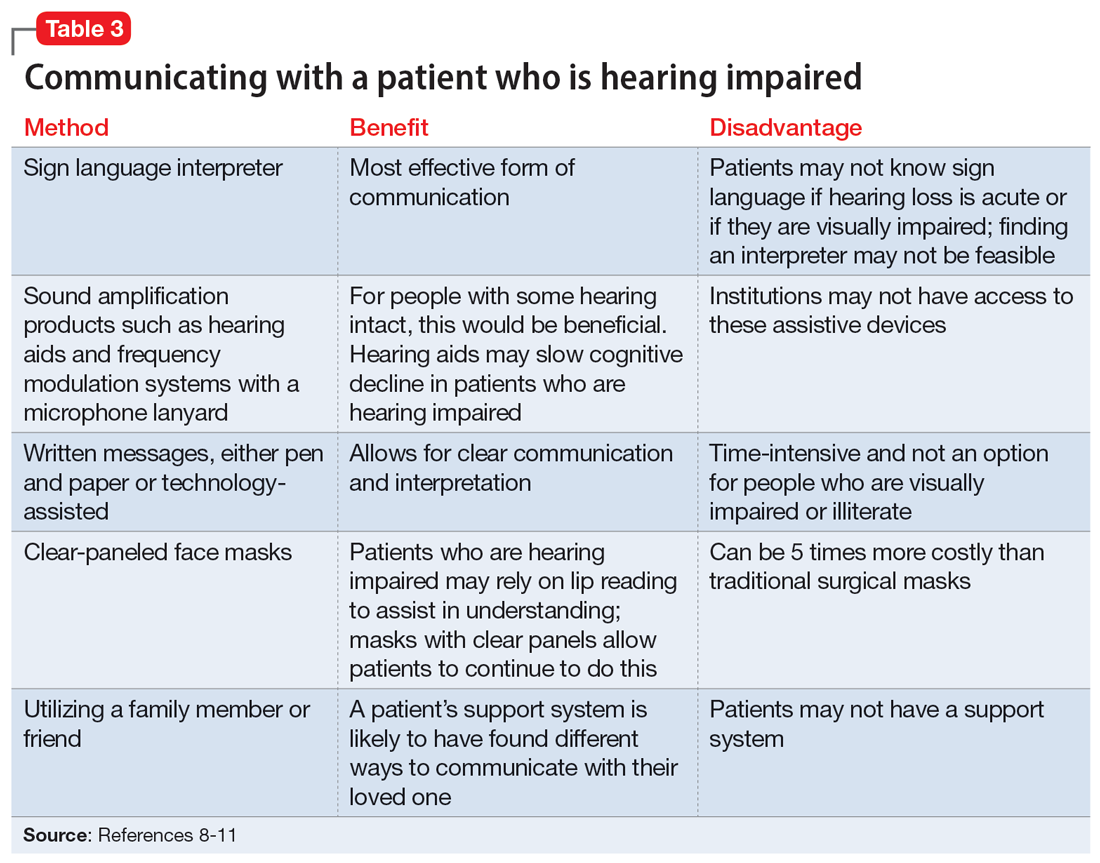

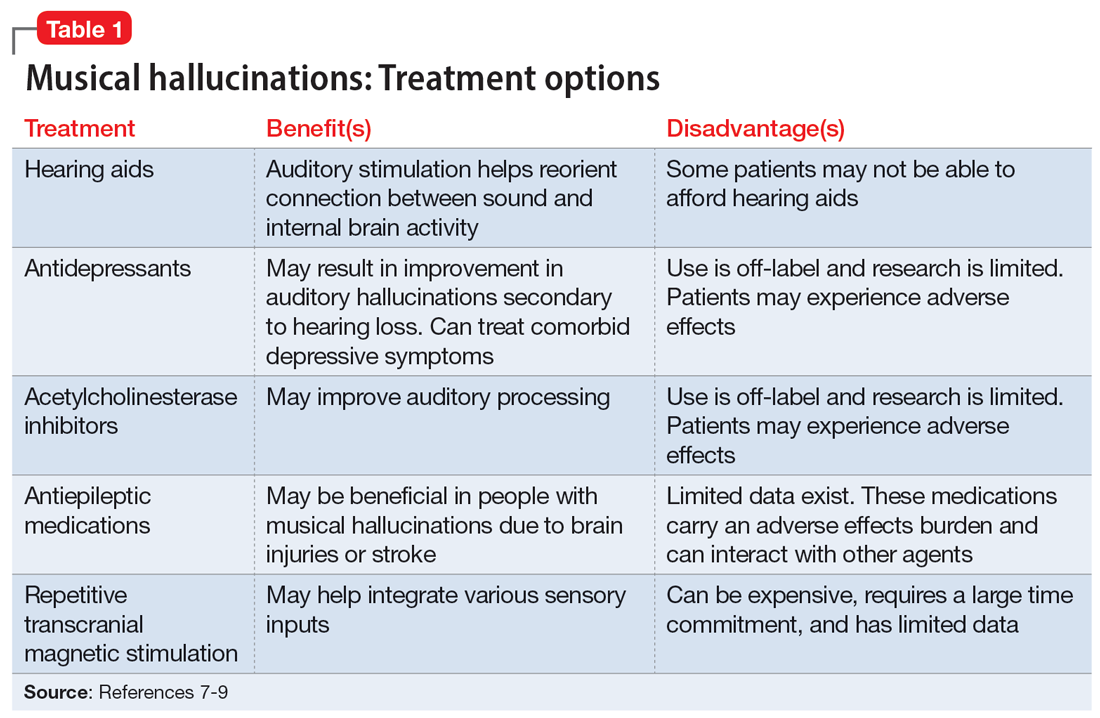

There is no consensus on treatment for MH. Current treatment guidance comes from case reports and case series. Treatment is generally most successful when the etiology of the hallucination is both apparent and treatable, such as an infectious eitiology.3 In the case of MH due to hearing loss, hallucinations may improve following treatment with hearing aids or cochlear implants,1,3,6,7 which is what was advised for Ms. L. Table 17-9 outlines other possible measures for addressing musical hallucinations.

Anticholinesterases, antidepressants, and antiepileptics may provide some benefit.8 However, pharmacotherapy is generally less efficacious and can cause adverse effects, so environmental support and hearing aids may be a safer approach. No medications have been shown to completely cure MH.

TREATMENT Hearing loss management and follow-up

When speaking with the consulting psychiatry team, Ms. L reports her outpatient psychotropic regimen has been helpful. The team decides to continue mirtazapine 30 mg/d and risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night. We recommend that Ms. L discuss tapering off risperidone with her outpatient clinician if they feel it may be indicated to reduce the risk of adverse effects. The treatment team decides not to start corticosteroids due to the risk of steroid-induced psychotic symptoms. The team discusses hallucinations related to hearing loss with Ms. L and advise her to follow up with Audiology and Otolaryngology in the outpatient setting.

The authors’ observations

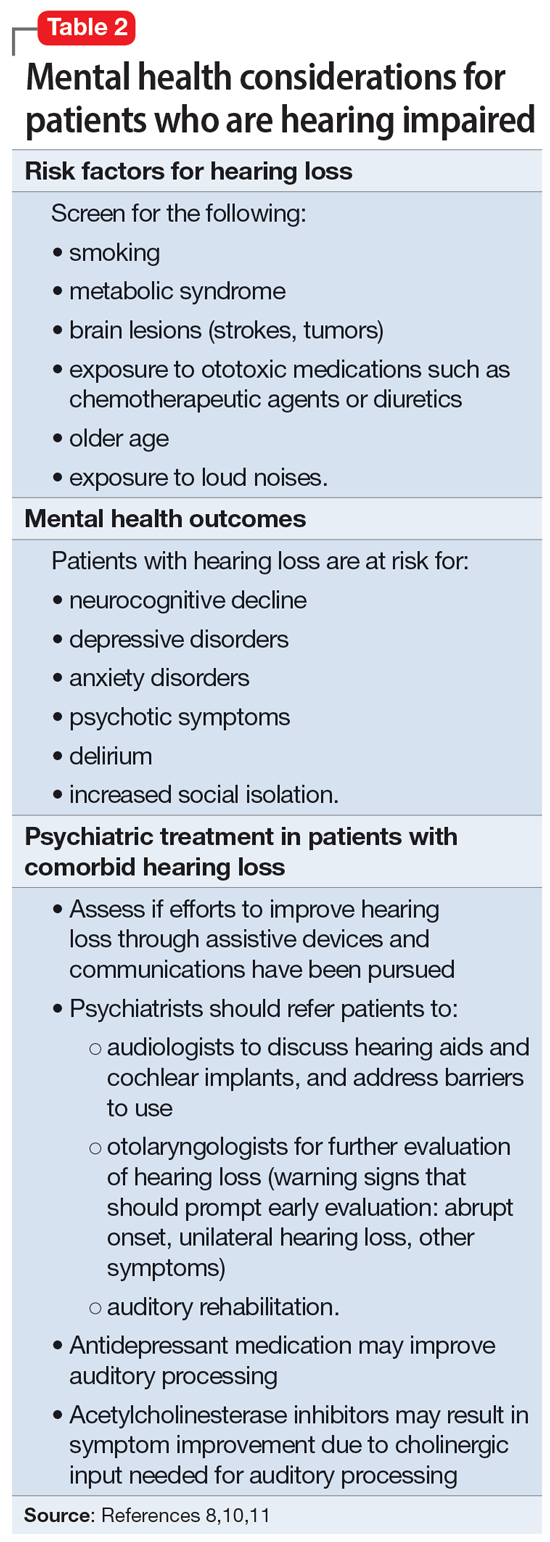

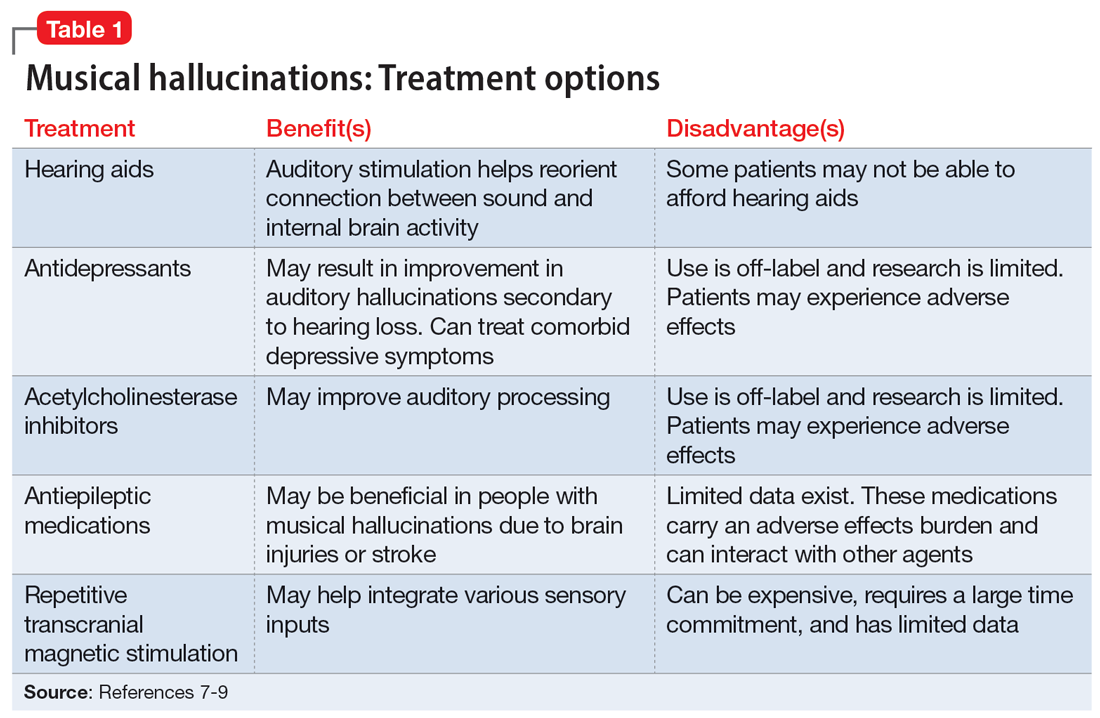

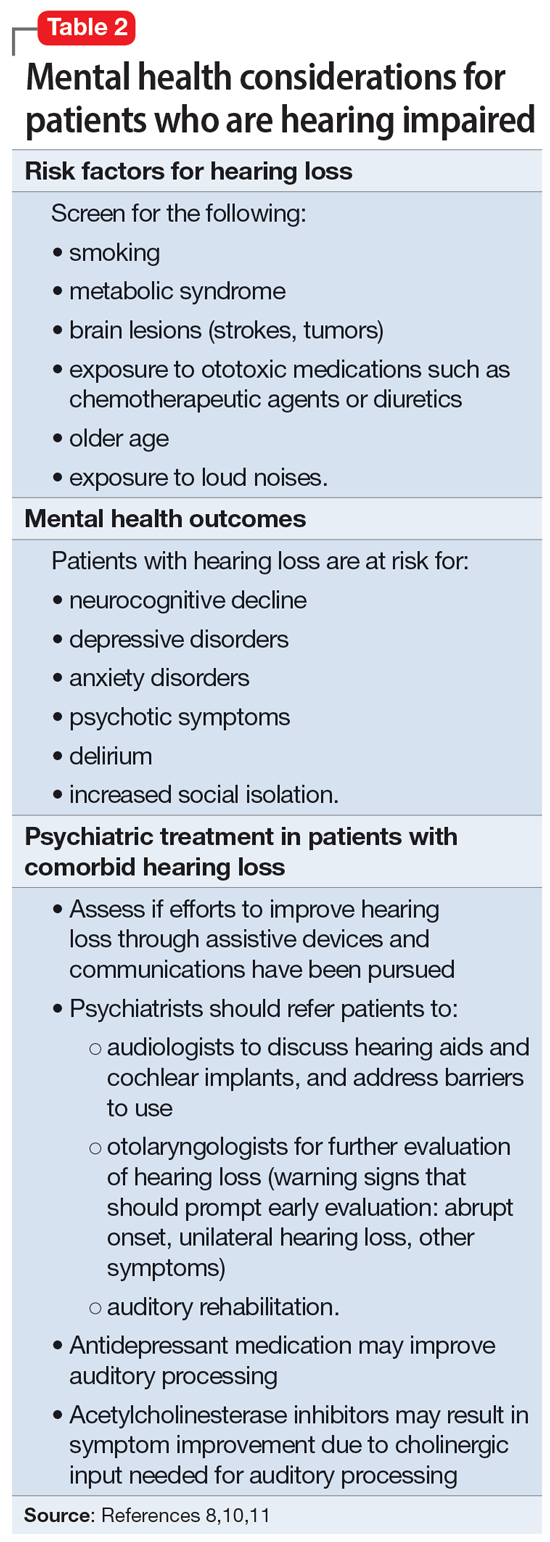

Approximately 40% of people age >60 struggle with hearing impairment4,9; this impacts their general quality of life and how clinicians communicate with such patients.10 People with hearing loss are more likely to develop feelings of social isolation, depression, and delirium (Table 28,10,11).11

Risk factors for hearing loss include tobacco use, metabolic syndrome, exposure to loud noises, and exposure to certain ototoxic medications such as chemotherapeutic agents.11 As psychiatrists, it is important to identify patients who may be at risk for hearing loss and refer them to the appropriate medical professional. If hearing loss is new onset, refer the patient to an otolaryngologist for a full evaluation. Unilateral hearing loss should warrant further workup because this could be due to an acoustic neuroma.11

When providing care for a patient who uses a hearing aid, discuss adherence, barriers to adherence, and difficulties with adjusting the hearing aid. A referral to an audiologist may help patients address these barriers. Patients with hearing impairment or loss may benefit from auditory rehabilitation programs that provide communication strategies, ways to adapt to hearing loss, and information about different assistive options.11 Such programs are often run by audiologists or speech language pathologists and contain both counseling and group components.

Continue to: Is is critical for psychiatrists...

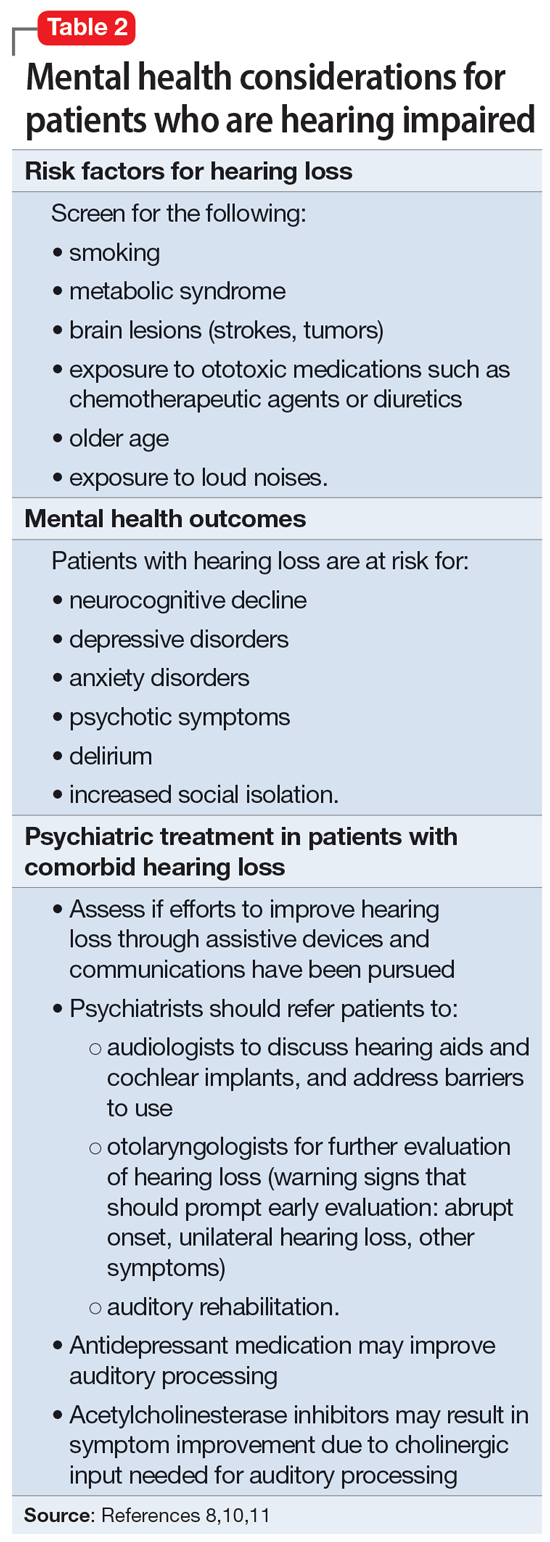

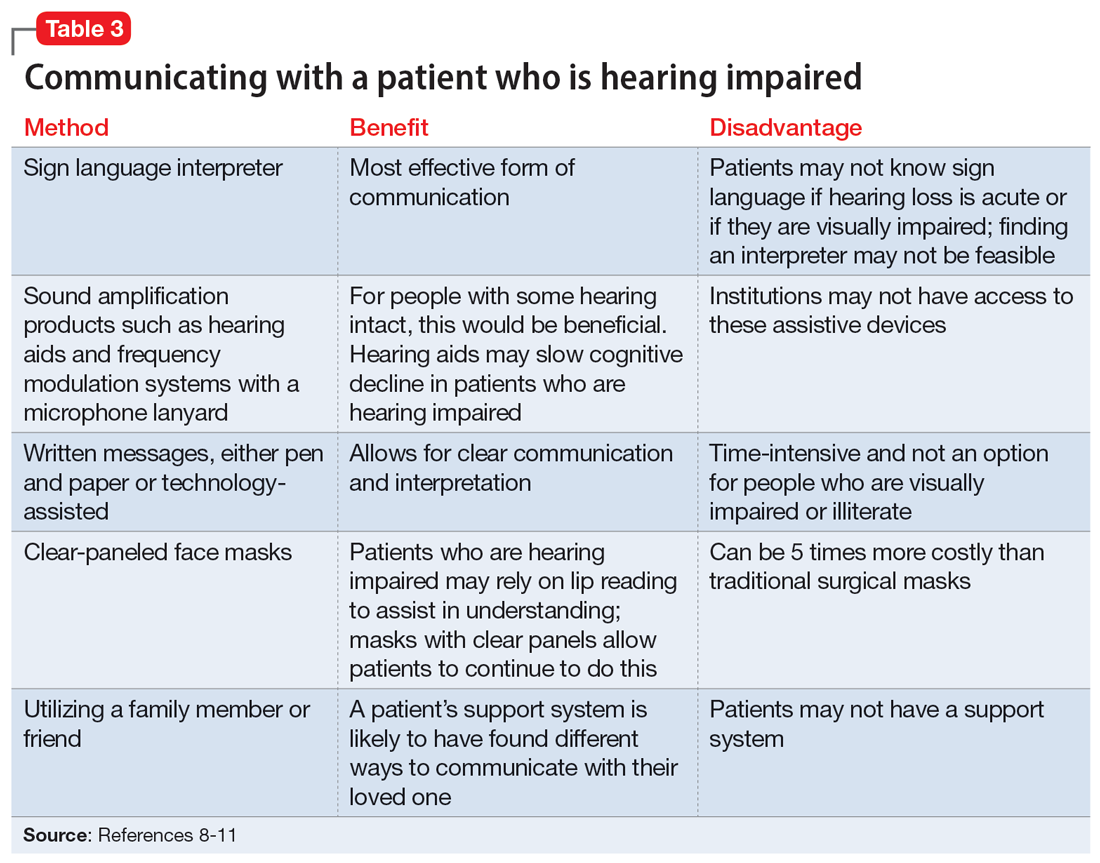

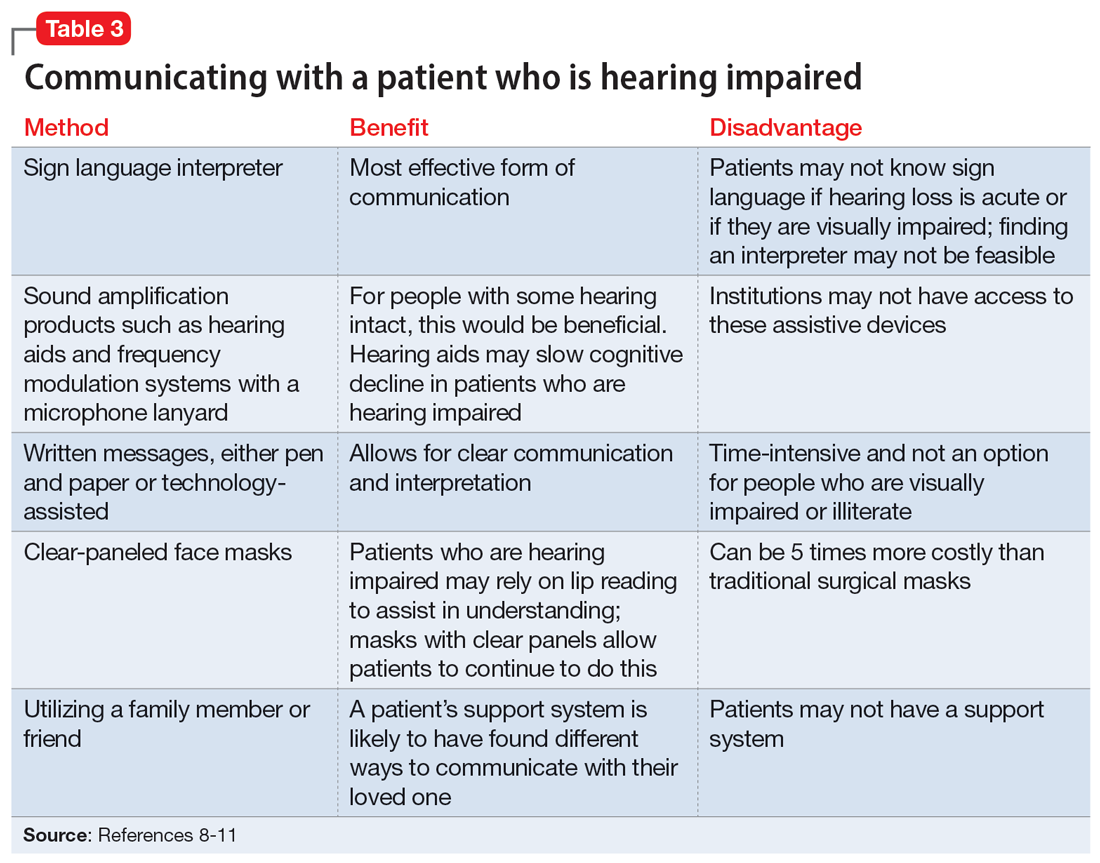

It is critical for psychiatrists to ensure appropriate communication with patients who are hearing impaired (Table 38-11). The use of assistive devices such as sound amplifiers, written messages, or family members to assist in communication is needed to prevent miscommunication.9-11

OUTCOME Lack of follow-up

A home health worker visits Ms. L, communicating with her using voice-to-text. Ms. L has not yet gone to her primary care physician, audiologist, or outpatient psychiatrist for follow-up because she needs to arrange transportation. Ms. L remains distressed by the music she is hearing, which is worse at night, along with her acute hearing loss.

Bottom Line

Hearing loss can predispose a person to psychiatric disorders and symptoms, including depression, delirium, and auditory hallucinations. Psychiatrists should strive to ensure clear communication with patients who are hearing impaired and should refer such patients to appropriate resources to improve outcomes.

Related Resources

- Wang J, Patel D, Francois D. Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):46-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0091

- Sosland MD, Pinninti N. 5 ways to quiet auditory hallucinations. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(4):110.

- Convery E, Keidser G, McLelland M, et al. A smartphone app to facilitate remote patient-provider communication in hearing health care: usability and effect on hearing aid outcomes. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(6):798-804. doi:10.1089/ tmj.2019.0109

Drug Brand Names

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Prednisone • Rayos

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valacyclovir • Valtrex

1. Cole MG, Dowson L, Dendukuri N, et al. The prevalence and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations among elderly subjects attending an audiology clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(5):444-452. doi:10.1002/gps.618

2. Alvarez Perez P, Garcia-Antelo MJ, Rubio-Nazabal E. “Doctor, I hear music”: a brief review about musical hallucinations. Open Neurol J. 2017;11:11-14. doi:10.2174/1874205X01711010011

3. Sanchez TG, Rocha SCM, Knobel KAB, et al. Musical hallucination associated with hearing loss. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69(2B):395-400. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2011000300024

4. Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MGM. Prevalence of musical hallucinations in patients referred for audiometric testing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(12):1075-1077. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823e31c4

5. Warner N, Aziz V. Hymns and arias: musical hallucinations in older people in Wales. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(7):658-660. doi:10.1002/gps.1338

6. Low WK, Tham CA, D’Souza VD, et al. Musical ear syndrome in adult cochlear implant patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(9):854-858. doi:10.1017/S0022215113001758

7. Brunner JP, Amedee RG. Musical hallucinations in a patient with presbycusis: a case report. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):89-91.

8. Coebergh JAF, Lauw RF, Bots R, et al. Musical hallucinations: review of treatment effects. Front Psychol. 2015;6:814. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00814

9. Ten Hulzen RD, Fabry DA. Impact of hearing loss and universal face masking in the COVID-19 era. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2069-2072. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.027

10. Shukla A, Nieman CL, Price C, et al. Impact of hearing loss on patient-provider communication among hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Am J Med Qual. 2019;34(3):284-292. doi:10.1177/1062860618798926

11. Blazer DG, Tucci DL. Hearing loss and psychiatric disorders: a review. Psychol Med. 2019;49(6):891-897. doi:10.1017/S0033291718003409

CASE New-onset auditory hallucinations

Ms. L, age 78, presents to our hospital with worsening anxiety due to auditory hallucinations. She has been hearing music, which she reports is worse at night and consists of songs, usually the song Jingle Bells, sometimes just melodies and other times with lyrics. Ms. L denies paranoia, visual hallucinations, or worsening mood.

Two weeks ago, Ms. L had visited another hospital, describing 5 days of right-side hearing loss accompanied by pain and burning in her ear and face, along with vesicular lesions in a dermatomal pattern extending into her auditory canal. During this visit, Ms. L’s complete blood count, urine culture, urine drug screen, electrolytes, liver panel, thyroid studies, and vitamin levels were unremarkable. A CT scan of her head showed no abnormalities.

Ms. L was diagnosed with Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), which affects cranial nerves, because of physical examination findings with a dermatomal pattern of lesion distribution and associated pain. Ramsay Hunt syndrome can cause facial paralysis and hearing loss in the affected ear. She was discharged with prescriptions for prednisone 60 mg/d for 7 days and valacyclovir 1 g/d for 7 days and told to follow up with her primary care physician. During the present visit to our hospital, Ms. L’s home health nurse reports that she still has her entire bottles of valacyclovir and prednisone left. Ms. L also has left-side hearing loss that began 5 years ago and a history of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder. Due to the recent onset of right-side hearing loss, her hearing impairment requires her to communicate via writing or via a voice-to-text app.

HISTORY Depressed and living alone

Ms. L was diagnosed with MDD more than 4 decades ago and has been receiving medication since then. She reports no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts, manic symptoms, or psychotic symptoms. For more than 20 years, she has seen a nurse practitioner, who had prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg/d for MDD, poor appetite, and sleep. Within the last 5 years, her nurse practitioner added risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night to augment the mirtazapine for tearfulness, irritability, and mood swings.

Ms. L’s medical history also includes hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She is a retired teacher and lives alone. She has a chore worker who visits her home for 1 hour 5 days a week to help with cleaning and lifting, and support from her son. Ms. L no longer drives and relies on others for transportation, but is able to manage her finances, activities of daily living, cooking, and walking without any assistance.

[polldaddy:12807642]

EVALUATION Identifying the cause of the music

Ms. L is alert and oriented to time and situation, her concentration is appropriate, and her recent and remote memories are preserved. A full cognitive screen is not performed, but she is able to spell WORLD forwards and backwards and adequately perform a serial 7s test. An examination of her ear does not reveal any open vesicular lesions or swelling, but she continues to report pain and tingling in the C7 dermatomal pattern. Her urine drug screen and infectious and autoimmune laboratory testing are unremarkable. She does not have electrolyte, renal function, or blood count abnormalities. An MRI of her brain that is performed to rule out intracranial pathology due to acute hearing loss shows no acute intracranial abnormalities, with some artifact effect due to motion. Because temporal lobe epilepsy can present with hallucinations,1 an EEG is performed to rule out seizure activity; it shows a normal wake pattern.

Psychiatry is consulted for management of the auditory hallucinations because Ms. L is distressed by hearing music. Ms. L is evaluated by Neurology and Otolaryngology. Neurology recommends a repeat brain MRI in the outpatient setting after seeing an artifact in the inpatient imaging, as well as follow-up with her primary care physician. Otolaryngology believes her symptoms are secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome with incomplete treatment, which is consistent with the initial diagnosis from her previous hospital visit, and recommends another course of oral corticosteroids, along with Audiology and Otolaryngology follow-up.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

This is the first case we have seen detailing musical hallucinations (MH) secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome, although musical hallucinations have been associated with other etiologies of hearing loss. MH is a “release phenomenon” believed to be caused by deprivation of stimulation of the auditory cortex.2 They are categorized as complex auditory hallucinations made up of melodies and rhythms and may be present in up to 2.5% of patients with hearing impairment.1 The condition is mostly seen in older adults because this population is more likely to experience hearing loss. MH is more common among women (70% to 80% of cases) and is highly comorbid with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or (as was the case for Ms. L) MDD.3 Hallucinations secondary to hearing loss may be more common in left-side hearing loss.4 In a 2005 study, Warner et al5 found religious music such as hymns or Christmas carols was most commonly heard, possibly due to repetitive past exposure.

There is no consensus on treatment for MH. Current treatment guidance comes from case reports and case series. Treatment is generally most successful when the etiology of the hallucination is both apparent and treatable, such as an infectious eitiology.3 In the case of MH due to hearing loss, hallucinations may improve following treatment with hearing aids or cochlear implants,1,3,6,7 which is what was advised for Ms. L. Table 17-9 outlines other possible measures for addressing musical hallucinations.

Anticholinesterases, antidepressants, and antiepileptics may provide some benefit.8 However, pharmacotherapy is generally less efficacious and can cause adverse effects, so environmental support and hearing aids may be a safer approach. No medications have been shown to completely cure MH.

TREATMENT Hearing loss management and follow-up

When speaking with the consulting psychiatry team, Ms. L reports her outpatient psychotropic regimen has been helpful. The team decides to continue mirtazapine 30 mg/d and risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night. We recommend that Ms. L discuss tapering off risperidone with her outpatient clinician if they feel it may be indicated to reduce the risk of adverse effects. The treatment team decides not to start corticosteroids due to the risk of steroid-induced psychotic symptoms. The team discusses hallucinations related to hearing loss with Ms. L and advise her to follow up with Audiology and Otolaryngology in the outpatient setting.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 40% of people age >60 struggle with hearing impairment4,9; this impacts their general quality of life and how clinicians communicate with such patients.10 People with hearing loss are more likely to develop feelings of social isolation, depression, and delirium (Table 28,10,11).11

Risk factors for hearing loss include tobacco use, metabolic syndrome, exposure to loud noises, and exposure to certain ototoxic medications such as chemotherapeutic agents.11 As psychiatrists, it is important to identify patients who may be at risk for hearing loss and refer them to the appropriate medical professional. If hearing loss is new onset, refer the patient to an otolaryngologist for a full evaluation. Unilateral hearing loss should warrant further workup because this could be due to an acoustic neuroma.11

When providing care for a patient who uses a hearing aid, discuss adherence, barriers to adherence, and difficulties with adjusting the hearing aid. A referral to an audiologist may help patients address these barriers. Patients with hearing impairment or loss may benefit from auditory rehabilitation programs that provide communication strategies, ways to adapt to hearing loss, and information about different assistive options.11 Such programs are often run by audiologists or speech language pathologists and contain both counseling and group components.

Continue to: Is is critical for psychiatrists...

It is critical for psychiatrists to ensure appropriate communication with patients who are hearing impaired (Table 38-11). The use of assistive devices such as sound amplifiers, written messages, or family members to assist in communication is needed to prevent miscommunication.9-11

OUTCOME Lack of follow-up

A home health worker visits Ms. L, communicating with her using voice-to-text. Ms. L has not yet gone to her primary care physician, audiologist, or outpatient psychiatrist for follow-up because she needs to arrange transportation. Ms. L remains distressed by the music she is hearing, which is worse at night, along with her acute hearing loss.

Bottom Line

Hearing loss can predispose a person to psychiatric disorders and symptoms, including depression, delirium, and auditory hallucinations. Psychiatrists should strive to ensure clear communication with patients who are hearing impaired and should refer such patients to appropriate resources to improve outcomes.

Related Resources

- Wang J, Patel D, Francois D. Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):46-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0091

- Sosland MD, Pinninti N. 5 ways to quiet auditory hallucinations. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(4):110.

- Convery E, Keidser G, McLelland M, et al. A smartphone app to facilitate remote patient-provider communication in hearing health care: usability and effect on hearing aid outcomes. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(6):798-804. doi:10.1089/ tmj.2019.0109

Drug Brand Names

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Prednisone • Rayos

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valacyclovir • Valtrex

CASE New-onset auditory hallucinations

Ms. L, age 78, presents to our hospital with worsening anxiety due to auditory hallucinations. She has been hearing music, which she reports is worse at night and consists of songs, usually the song Jingle Bells, sometimes just melodies and other times with lyrics. Ms. L denies paranoia, visual hallucinations, or worsening mood.

Two weeks ago, Ms. L had visited another hospital, describing 5 days of right-side hearing loss accompanied by pain and burning in her ear and face, along with vesicular lesions in a dermatomal pattern extending into her auditory canal. During this visit, Ms. L’s complete blood count, urine culture, urine drug screen, electrolytes, liver panel, thyroid studies, and vitamin levels were unremarkable. A CT scan of her head showed no abnormalities.

Ms. L was diagnosed with Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), which affects cranial nerves, because of physical examination findings with a dermatomal pattern of lesion distribution and associated pain. Ramsay Hunt syndrome can cause facial paralysis and hearing loss in the affected ear. She was discharged with prescriptions for prednisone 60 mg/d for 7 days and valacyclovir 1 g/d for 7 days and told to follow up with her primary care physician. During the present visit to our hospital, Ms. L’s home health nurse reports that she still has her entire bottles of valacyclovir and prednisone left. Ms. L also has left-side hearing loss that began 5 years ago and a history of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder. Due to the recent onset of right-side hearing loss, her hearing impairment requires her to communicate via writing or via a voice-to-text app.

HISTORY Depressed and living alone

Ms. L was diagnosed with MDD more than 4 decades ago and has been receiving medication since then. She reports no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts, manic symptoms, or psychotic symptoms. For more than 20 years, she has seen a nurse practitioner, who had prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg/d for MDD, poor appetite, and sleep. Within the last 5 years, her nurse practitioner added risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night to augment the mirtazapine for tearfulness, irritability, and mood swings.

Ms. L’s medical history also includes hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She is a retired teacher and lives alone. She has a chore worker who visits her home for 1 hour 5 days a week to help with cleaning and lifting, and support from her son. Ms. L no longer drives and relies on others for transportation, but is able to manage her finances, activities of daily living, cooking, and walking without any assistance.

[polldaddy:12807642]

EVALUATION Identifying the cause of the music

Ms. L is alert and oriented to time and situation, her concentration is appropriate, and her recent and remote memories are preserved. A full cognitive screen is not performed, but she is able to spell WORLD forwards and backwards and adequately perform a serial 7s test. An examination of her ear does not reveal any open vesicular lesions or swelling, but she continues to report pain and tingling in the C7 dermatomal pattern. Her urine drug screen and infectious and autoimmune laboratory testing are unremarkable. She does not have electrolyte, renal function, or blood count abnormalities. An MRI of her brain that is performed to rule out intracranial pathology due to acute hearing loss shows no acute intracranial abnormalities, with some artifact effect due to motion. Because temporal lobe epilepsy can present with hallucinations,1 an EEG is performed to rule out seizure activity; it shows a normal wake pattern.

Psychiatry is consulted for management of the auditory hallucinations because Ms. L is distressed by hearing music. Ms. L is evaluated by Neurology and Otolaryngology. Neurology recommends a repeat brain MRI in the outpatient setting after seeing an artifact in the inpatient imaging, as well as follow-up with her primary care physician. Otolaryngology believes her symptoms are secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome with incomplete treatment, which is consistent with the initial diagnosis from her previous hospital visit, and recommends another course of oral corticosteroids, along with Audiology and Otolaryngology follow-up.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

This is the first case we have seen detailing musical hallucinations (MH) secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome, although musical hallucinations have been associated with other etiologies of hearing loss. MH is a “release phenomenon” believed to be caused by deprivation of stimulation of the auditory cortex.2 They are categorized as complex auditory hallucinations made up of melodies and rhythms and may be present in up to 2.5% of patients with hearing impairment.1 The condition is mostly seen in older adults because this population is more likely to experience hearing loss. MH is more common among women (70% to 80% of cases) and is highly comorbid with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or (as was the case for Ms. L) MDD.3 Hallucinations secondary to hearing loss may be more common in left-side hearing loss.4 In a 2005 study, Warner et al5 found religious music such as hymns or Christmas carols was most commonly heard, possibly due to repetitive past exposure.

There is no consensus on treatment for MH. Current treatment guidance comes from case reports and case series. Treatment is generally most successful when the etiology of the hallucination is both apparent and treatable, such as an infectious eitiology.3 In the case of MH due to hearing loss, hallucinations may improve following treatment with hearing aids or cochlear implants,1,3,6,7 which is what was advised for Ms. L. Table 17-9 outlines other possible measures for addressing musical hallucinations.

Anticholinesterases, antidepressants, and antiepileptics may provide some benefit.8 However, pharmacotherapy is generally less efficacious and can cause adverse effects, so environmental support and hearing aids may be a safer approach. No medications have been shown to completely cure MH.

TREATMENT Hearing loss management and follow-up

When speaking with the consulting psychiatry team, Ms. L reports her outpatient psychotropic regimen has been helpful. The team decides to continue mirtazapine 30 mg/d and risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night. We recommend that Ms. L discuss tapering off risperidone with her outpatient clinician if they feel it may be indicated to reduce the risk of adverse effects. The treatment team decides not to start corticosteroids due to the risk of steroid-induced psychotic symptoms. The team discusses hallucinations related to hearing loss with Ms. L and advise her to follow up with Audiology and Otolaryngology in the outpatient setting.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 40% of people age >60 struggle with hearing impairment4,9; this impacts their general quality of life and how clinicians communicate with such patients.10 People with hearing loss are more likely to develop feelings of social isolation, depression, and delirium (Table 28,10,11).11

Risk factors for hearing loss include tobacco use, metabolic syndrome, exposure to loud noises, and exposure to certain ototoxic medications such as chemotherapeutic agents.11 As psychiatrists, it is important to identify patients who may be at risk for hearing loss and refer them to the appropriate medical professional. If hearing loss is new onset, refer the patient to an otolaryngologist for a full evaluation. Unilateral hearing loss should warrant further workup because this could be due to an acoustic neuroma.11

When providing care for a patient who uses a hearing aid, discuss adherence, barriers to adherence, and difficulties with adjusting the hearing aid. A referral to an audiologist may help patients address these barriers. Patients with hearing impairment or loss may benefit from auditory rehabilitation programs that provide communication strategies, ways to adapt to hearing loss, and information about different assistive options.11 Such programs are often run by audiologists or speech language pathologists and contain both counseling and group components.

Continue to: Is is critical for psychiatrists...

It is critical for psychiatrists to ensure appropriate communication with patients who are hearing impaired (Table 38-11). The use of assistive devices such as sound amplifiers, written messages, or family members to assist in communication is needed to prevent miscommunication.9-11

OUTCOME Lack of follow-up

A home health worker visits Ms. L, communicating with her using voice-to-text. Ms. L has not yet gone to her primary care physician, audiologist, or outpatient psychiatrist for follow-up because she needs to arrange transportation. Ms. L remains distressed by the music she is hearing, which is worse at night, along with her acute hearing loss.

Bottom Line

Hearing loss can predispose a person to psychiatric disorders and symptoms, including depression, delirium, and auditory hallucinations. Psychiatrists should strive to ensure clear communication with patients who are hearing impaired and should refer such patients to appropriate resources to improve outcomes.

Related Resources

- Wang J, Patel D, Francois D. Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):46-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0091

- Sosland MD, Pinninti N. 5 ways to quiet auditory hallucinations. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(4):110.

- Convery E, Keidser G, McLelland M, et al. A smartphone app to facilitate remote patient-provider communication in hearing health care: usability and effect on hearing aid outcomes. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(6):798-804. doi:10.1089/ tmj.2019.0109

Drug Brand Names

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Prednisone • Rayos

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valacyclovir • Valtrex

1. Cole MG, Dowson L, Dendukuri N, et al. The prevalence and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations among elderly subjects attending an audiology clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(5):444-452. doi:10.1002/gps.618

2. Alvarez Perez P, Garcia-Antelo MJ, Rubio-Nazabal E. “Doctor, I hear music”: a brief review about musical hallucinations. Open Neurol J. 2017;11:11-14. doi:10.2174/1874205X01711010011

3. Sanchez TG, Rocha SCM, Knobel KAB, et al. Musical hallucination associated with hearing loss. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69(2B):395-400. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2011000300024

4. Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MGM. Prevalence of musical hallucinations in patients referred for audiometric testing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(12):1075-1077. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823e31c4

5. Warner N, Aziz V. Hymns and arias: musical hallucinations in older people in Wales. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(7):658-660. doi:10.1002/gps.1338

6. Low WK, Tham CA, D’Souza VD, et al. Musical ear syndrome in adult cochlear implant patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(9):854-858. doi:10.1017/S0022215113001758

7. Brunner JP, Amedee RG. Musical hallucinations in a patient with presbycusis: a case report. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):89-91.

8. Coebergh JAF, Lauw RF, Bots R, et al. Musical hallucinations: review of treatment effects. Front Psychol. 2015;6:814. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00814

9. Ten Hulzen RD, Fabry DA. Impact of hearing loss and universal face masking in the COVID-19 era. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2069-2072. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.027

10. Shukla A, Nieman CL, Price C, et al. Impact of hearing loss on patient-provider communication among hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Am J Med Qual. 2019;34(3):284-292. doi:10.1177/1062860618798926

11. Blazer DG, Tucci DL. Hearing loss and psychiatric disorders: a review. Psychol Med. 2019;49(6):891-897. doi:10.1017/S0033291718003409

1. Cole MG, Dowson L, Dendukuri N, et al. The prevalence and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations among elderly subjects attending an audiology clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(5):444-452. doi:10.1002/gps.618

2. Alvarez Perez P, Garcia-Antelo MJ, Rubio-Nazabal E. “Doctor, I hear music”: a brief review about musical hallucinations. Open Neurol J. 2017;11:11-14. doi:10.2174/1874205X01711010011

3. Sanchez TG, Rocha SCM, Knobel KAB, et al. Musical hallucination associated with hearing loss. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69(2B):395-400. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2011000300024

4. Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MGM. Prevalence of musical hallucinations in patients referred for audiometric testing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(12):1075-1077. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823e31c4

5. Warner N, Aziz V. Hymns and arias: musical hallucinations in older people in Wales. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(7):658-660. doi:10.1002/gps.1338

6. Low WK, Tham CA, D’Souza VD, et al. Musical ear syndrome in adult cochlear implant patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(9):854-858. doi:10.1017/S0022215113001758

7. Brunner JP, Amedee RG. Musical hallucinations in a patient with presbycusis: a case report. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):89-91.

8. Coebergh JAF, Lauw RF, Bots R, et al. Musical hallucinations: review of treatment effects. Front Psychol. 2015;6:814. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00814

9. Ten Hulzen RD, Fabry DA. Impact of hearing loss and universal face masking in the COVID-19 era. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2069-2072. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.027

10. Shukla A, Nieman CL, Price C, et al. Impact of hearing loss on patient-provider communication among hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Am J Med Qual. 2019;34(3):284-292. doi:10.1177/1062860618798926

11. Blazer DG, Tucci DL. Hearing loss and psychiatric disorders: a review. Psychol Med. 2019;49(6):891-897. doi:10.1017/S0033291718003409

An unquenchable thirst

CASE Unresponsive after a presumed seizure

Mr. F, age 44, has schizophrenia. He is brought to the hospital by ambulance after he is found on the ground outside of his mother’s house following a presumed seizure and fall. On arrival to the emergency department, he is unresponsive. His laboratory values are significant for a sodium level of 110 mEq/L (reference range: 135 to 145 mEq/L), indicating hyponatremia.

HISTORY Fixated on purity

Mr. F’s mother reports that Mr. F had an unremarkable childhood. He was raised in a household with both parents and a younger sister. Mr. F did well academically and studied engineering and physics in college. There was no reported history of trauma or substance use.

During his senior year of college, Mr. F began experiencing paranoia, auditory hallucinations, and religious delusions. He required hospitalization and was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Following multiple hospitalizations over 5 years, he moved in with his mother, who was granted guardianship.

His mother said Mr. F’s religious delusions were of purity and cleansing the soul. He spent hours memorizing the Bible and would go for days without eating but would drink large amounts of water. She said she thought this was due to his desire to flush out imperfections.

In the past 3 years, Mr. F has been hospitalized several times for severe hyponatremia. At home, his mother attempted to restrict his water intake. However, Mr. F would still drink out of sinks and hoses. Mr. F’s mother reports that over the past month he had become more isolated. He would spend entire days reading the Bible, and his water intake had further increased.

Prior medication trials for Mr. F included haloperidol, up to 10 mg twice per day; aripiprazole, up to 20 mg/d; and risperidone, up to 6 mg nightly. These had been effective, but Mr. F had difficulty with adherence. He did not receive a long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic initially due to lack of access at the rural clinic where he was treated, and later due to his mother’s preference for her son to receive oral medications. Prior to his current presentation, Mr. F’s medication regimen was olanzapine, 10 mg twice a day; perphenazine, 8 mg twice a day; and long-acting propranolol, 60 mg/d. Mr. F had no other chronic medical problems.

EVALUATION Hyponatremia, but why?

Mr. F is intubated and admitted to the surgical service for stabilization due to injuries from his fall. He has fractures of his right sinus and bilateral nasal bones, which are managed nonoperatively. He is delirious, with waxing and waning attention, memory disturbances, and disorientation. His psychotropic medications are held.

Continue to: Imaging of his head...

Imaging of his head does not reveal acute abnormalities suggesting a malignant or paraneoplastic process, and there are no concerns for ongoing seizures. An infection workup is negative. His urine toxicology is negative and blood alcohol level is 0. His sodium normalizes after 3 days of IV fluids and fluid restriction. Therefore, further tests to differentiate the causes of hyponatremia, such as urine electrolytes and urine osmolality, are not pursued.

[polldaddy:10910406]

The authors’ observations

The differential diagnosis for hyponatremia is broad in the setting of psychiatric illness. Low sodium levels could be due to psychotropic medications, psychiatrically-driven behaviors, or an underlying medical problem. Our differential diagnosis for Mr. F included iatrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), diabetes insipidus, or psychogenic polydipsia, a form of primary polydipsia. Other causes of primary polydipsia are related to substances, such as heavy beer intakeor use of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, also known as “ecstasy”), or brain lesions,1 but these causes were less likely given Mr. F’s negative urine toxicology and head imaging.

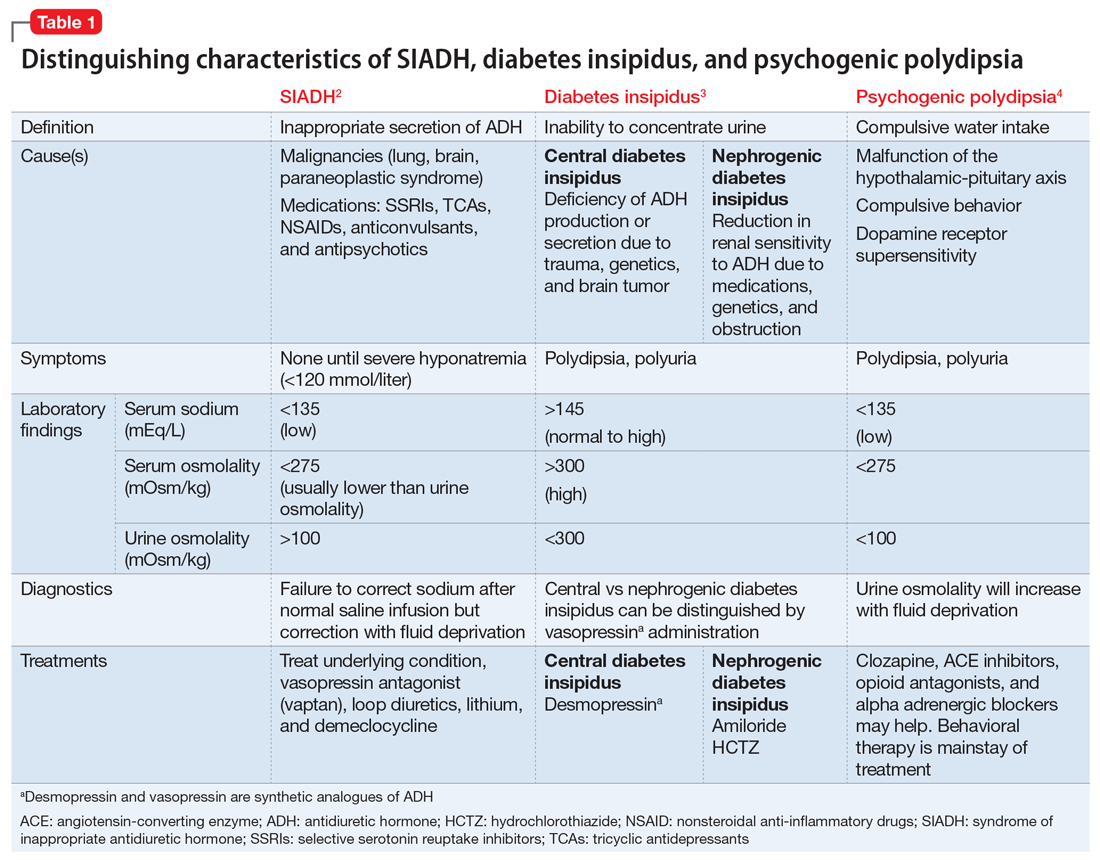

While psychogenic polydipsia is due to increased water consumption, both SIADH and diabetes insipidus are due to alterations in fluid homeostasis.2,3 Table 12-4 outlines distinguishing characteristics of SIADH, diabetes insipidus, and psychogenic polydipsia. Urine studies were not pursued because Mr. F’s sodium resolved and acute concerns, such as malignancy or infection, were ruled out. Mr. F’s hyponatremia was presumed to be due to psychogenic polydipsia because of his increased fluid intake and normalization of sodium with hypertonic fluids and subsequent fluid restriction. During this time, he was managed on the surgical service; the plan was to pursue urine studies and possibly a fluid challenge if his hyponatremia persisted.

EVALUATION Delirium resolves, delusions persist

While Mr. F is on the surgical service, the treatment team focuses on stabilizing his sodium level and assessing for causes of altered mental status that led to his fall. Psychiatry is consulted for management of his agitation. Following the gradual correction of his sodium level and extubation, his sensorium improves. By hospital Day 5, Mr. F’s delirium resolves.

During this time, Mr. F’s disorganization and religious delusions become apparent. He spends much of his time reading his Bible. He has poor hygiene and limited engagement in activities of daily living. Due to his psychosis and inability to care for himself, Mr. F is transferred to the psychiatric unit with consent from his mother.

Continue to: TREATMENT Olanzapine and fluid restriction

TREATMENT Olanzapine and fluid restriction

In the psychiatric unit, Mr. F is restarted on olanzapine, but not on perphenazine due to anticholinergic effects and not on propranolol due to continued orthostatic hypotension. Five days later, he is at his baseline level of functioning with residual psychosis. His fluid intake is restricted to <1.5 L per day and he is easily compliant.

Mr. F’s mother is comfortable with his discharge home on a regimen of olanzapine, 25 mg/d, and the team discusses the fluid restrictions with her. The treatment team suggests initiating an LAI before Mr. F is discharged, but this is not pursued because his mother thinks he is doing well with the oral medication. She wants to monitor him with the medication changes in the clinic before pursuing an LAI; however, she is open to it in the future.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 20% of patients with schizophrenia may experience psychogenic polydipsia.4,5 The cause of psychogenic polydipsia in patients with serious mental illness is multifactorial. It may stem from malfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, which leads to alterations in antidiuretic hormone secretion and function.4-6

Mr. F’s case highlights several challenges associated with treating psychogenic polydipsia in patients with serious mental illness. Antipsychotics with high dopamine affinity, such as risperidone and haloperidol, may increase the risk of psychogenic polydipsia, while antipsychotics with lower dopamine affinity, such as clozapine, may decrease the occurrence.5 Antipsychotics block postsynaptic dopamine receptors, which can induce supersensitivity by increasing presynaptic dopamine release in the hypothalamic areas, where thirst regulation occurs. This increase in dopamine leads to increased thirst drive and fluid intake.3

Quetiapine or clozapine may have been a better antipsychotic choice because these agents have lower D2 receptor affinity, whereas olanzapine has intermediate binding to D2 receptors.6,7 However, quetiapine and clozapine are more strongly associated with orthostasis, which was a concern during Mr. F’s hospitalization. The weekly laboratory testing required with clozapine use would have been an unfeasible burden for Mr. F because he lived in a rural environment. Perphenazine was not continued due to higher D2 affinity and anticholinergic effects, which can increase thirst.6

Continue to: In addition to switching...

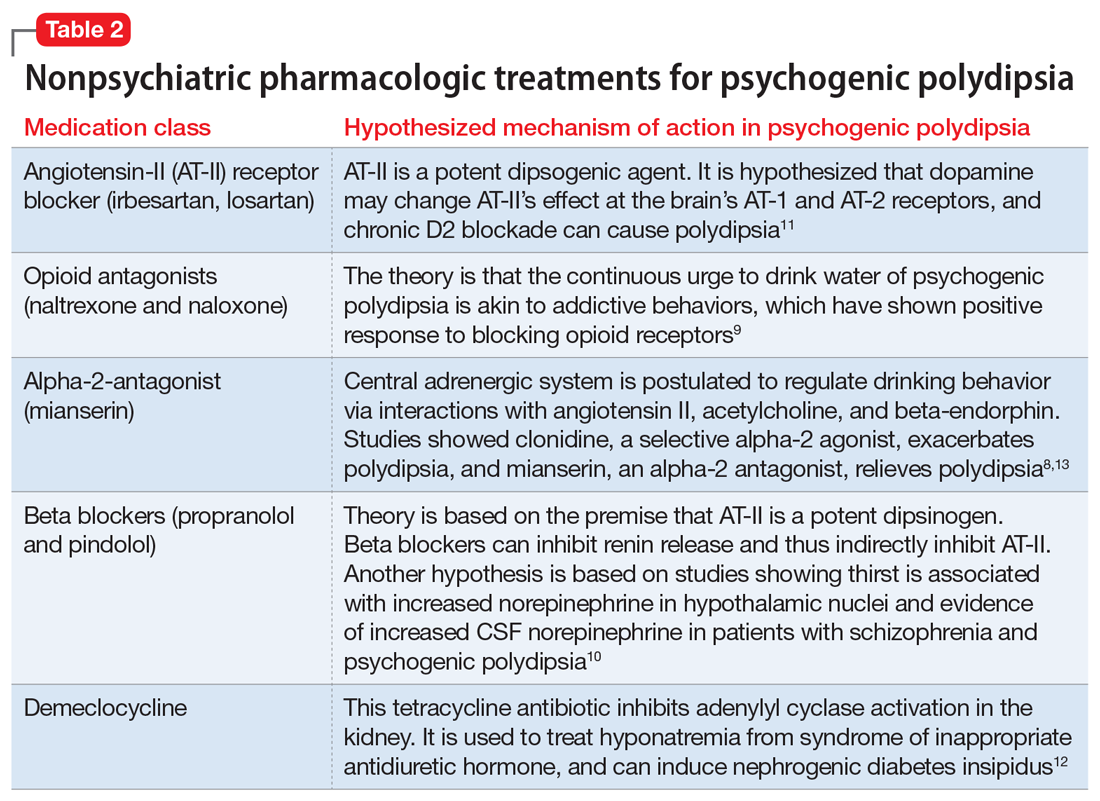

In addition to switching to an antipsychotic with looser D2 binding, other medications for treating polydipsia have been studied. It is hypothesized that the alpha-2 adrenergic system may play a role in thirst regulation. For example, mianserin, an alpha-2 antagonist, may decrease water intake. However, studies have been small and inconsistent.8,9 Propranolol,10 a beta adrenergic receptor blocker; irbesartan,11 an angiotensin-II receptor blocker; demeclocycline,12 a tetracycline that inhibits antidiuretic hormone action; and naltrexone,9 a mu opioid antagonist, have been studied with inconclusive results and a variety of adverse effects5,7,13 (Table 28-13).

Behavioral interventions for patients with psychogenic polydipsia include fluid restriction, twice-daily weight checks, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and reinforcement schedules, which may be useful but less realistic due to need for increased supervision.11,12 Patient and family education on the signs of hyponatremia are important to prevent serious complications, such as those Mr. F experienced.

OUTCOME Repeated hospitalizations

Mr. F is discharged with follow-up in our psychiatry clinic and attends 1 appointment. At that time, his mother reports that Mr. F is compliant with his medication and has limited fluid intake. However, over the next 2 months, he is admitted to our psychiatric unit twice with similar presentations. Each time, the treatment team has extensive discussions with Mr. F’s mother about strategies to limit his water intake and the possibility of residential placement due to his need for a higher level of care. Although she acknowledges that nursing home placement may be needed in the future, she is not ready to take this step.

Three months later, Mr. F returns to our hospital with severe abdominal pain and is found to have a perforated bowel obstruction. His sodium is within normal limits on presentation, and the psychiatry team is not involved during this hospitalization. Mr. F is treated for sepsis and undergoes 3 exploratory laparotomies with continued decline in his health. He dies during this hospitalization. The cause of Mr. F’s perforated bowel obstruction is not determined, and his family does not pursue an autopsy.

The authors’ observations

At Mr. F’s final hospital presentation, his sodium was normal. It is possible Mr. F and his mother had found an acceptable fluid restriction routine, and he may have been doing better from a psychiatric perspective, but this will remain unknown.

Continue to: This case highlights...

This case highlights the clinical and ethical complexity of treating patients with psychogenic polydipsia. Because Mr. F no longer had autonomy, we had to determine if his mother was acting in his best interest as his guardian. Guardianship requirements and expectations vary by state. In our state of Missouri, a guardian is appointed by the court to act in the best interest of the ward, and may be a family member (preferred) or state-appointed. The guardian is responsible for providing the ward’s care and is in charge of financial and medical decisions. In Missouri, the guardian must assure the ward resides in the “least restrictive setting reasonably available,” which is the minimum necessary to provide the ward safe care and housing.14 Full guardianship, as in Mr. F’s case, is different from limited guardianship, which is an option in states such as Missouri. In limited guardianship, the court decides the extent of the guardian’s role in decisions for the ward.14,15

Mr. F’s mother believed she was acting in her son’s best interest by having him home with his family. She believed by living at home, he would derive more enjoyment from life than living in a nursing home. By the time Mr. F presented to our hospital, he had been living with decompensated schizophrenia for years, so some level of psychosis was likely to persist, even with treatment. Given his increasingly frequent hospitalizations for hyponatremia due to increased water intake, more intense supervision may have been needed to maintain his safety, in line with nonmaleficence. The treatment team considered Mr. F’s best interest when discussing placement and worked to understand his mother’s preferences.

His mother continued to acknowledge the need for changes and adjustments at home. She was receptive to the need for fluid restriction and increased structure at home. Therefore, we felt she continued to be acting in his best interest, and his home would be the least restrictive setting for his care. If Mr. F had continued to require repeated hospitalizations and had not passed away, we would have pursued an ethics consult to discuss the need for nursing home placement and how to best approach this with Mr. F’s mother.

Bottom Line

Patients with serious mental illness who present with hyponatremia should be evaluated for psychogenic polydipsia by assessing their dietary and fluid intakes, along with collateral from family. The use of antipsychotics with high dopamine affinity may increase the risk of psychogenic polydipsia. Behavioral interventions include fluid restriction, weight checks, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and reinforcement schedules.

Related Resources

- Sharp CS, Wilson MP. Hyponatremia. In: Nordstrom KD, Wilson MP, eds. Quick guide to psychiatric emergencies. Springer International Publishing; 2018:115-119. doi:10.1007/ 978-3-319-58260-3_21

- Sailer C, Winzeler B, Christ-Crain M. Primary polydipsia in the medical and psychiatric patient: characteristics, complications and therapy. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14514. doi:10.4414/ smw.2017.14514

Drug Brand Names

Amiloride • Midamor

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Demeclocycline • Declomycin

Desmopressin • DDAVP

Haloperidol • Haldol

Irbesartan • Avapro

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Losartan • Cozaar

Mianserin • Tolvon

Naloxone • Narcan

Naltrexone • Revia

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Perphenazine • Trilafon

Propranolol • Inderal LA

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperda

1. Sharp CS, Wilson MP. Hyponatremia. In: Nordstrom KD, Wilson MP, eds. Quick guide to psychiatric emergencies. Springer International Publishing; 2018:115-119. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-58260-3_21

2. Gross P. Clinical management of SIADH. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2012;3(2):61-73. doi:10.1177/2042018812437561

3. Christ-Crain M, Bichet DG, Fenske WK, et al. Diabetes insipidus. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2019;5(1):54. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0103-2

4. Ahmadi L, Goldman MB. Primary polydipsia: update. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;34(5):101469. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2020.101469

5. Kirino S, Sakuma M, Misawa F, et al. Relationship between polydipsia and antipsychotics: a systematic review of clinical studies and case reports. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;96:109756. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109756

6. Siafis S, Tzachanis D, Samara M, et al. Antipsychotic drugs: from receptor-binding profiles to metabolic side effects. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(8):1210-1223. doi:10.2174/1570159X15666170630163616

7. Seeman P, Tallerico T. Antipsychotic drugs which elicit little or no parkinsonism bind more loosely than dopamine to brain D2 receptors, yet occupy high levels of these receptors. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3(2):123-134. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000336

8. Hayashi T, Nishikawa T, Koga I, et al. Involvement of the α 2 -adrenergic system in polydipsia in schizophrenic patients: a pilot study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1997;130(4):382-386. doi:10.1007/s002130050254

9. Rizvi S, Gold J, Khan AM. Role of naltrexone in improving compulsive drinking in psychogenic polydipsia. Cureus. 2019;11(8):e5320. doi:10.7759/cureus.5320

10. Kishi Y, Kurosawa H, Endo S. Is propranolol effective in primary polydipsia? Int J Psychiatry Med. 1998;28(3):315-325. doi:10.2190/QPWL-14H7-HPGG-A29D

11. Kruse D, Pantelis C, Rudd R, et al. Treatment of psychogenic polydipsia: comparison of risperidone and olanzapine, and the effects of an adjunctive angiotensin-II receptor blocking drug (irbesartan). Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(1):65-68. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00847.x

12. Alexander RC, Karp BI, Thompson S, et al. A double blind, placebo-controlled trial of demeclocycline treatment of polydipsia-hyponatremia in chronically psychotic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1991;30(4):417-420. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(91)90300-B

13. Valente S, Fisher D. Recognizing and managing psychogenic polydipsia in mental health. J Nurse Pract. 2010;6(7):546-550. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2010.03.004

14. Barton R, Esq SL, Lockett LL. The use of conservatorships and adult guardianships and other options in the care of the mentally ill in the United States. World Guard Congr. Published May 29, 2014. Accessed June 18, 2021. http://www.guardianship.org/IRL/Resources/Handouts/Family%20Members%20as%20Guardians_Handout.pdf

15. ABA Commission on Law & Aging. Adult Guardianship Statutory Table of Authorities. ABA. Published January 2021. Accessed June 17, 2021. https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/law_aging/2019-adult-guardianship-statutory-table-of-authorities.pdf

CASE Unresponsive after a presumed seizure

Mr. F, age 44, has schizophrenia. He is brought to the hospital by ambulance after he is found on the ground outside of his mother’s house following a presumed seizure and fall. On arrival to the emergency department, he is unresponsive. His laboratory values are significant for a sodium level of 110 mEq/L (reference range: 135 to 145 mEq/L), indicating hyponatremia.

HISTORY Fixated on purity

Mr. F’s mother reports that Mr. F had an unremarkable childhood. He was raised in a household with both parents and a younger sister. Mr. F did well academically and studied engineering and physics in college. There was no reported history of trauma or substance use.

During his senior year of college, Mr. F began experiencing paranoia, auditory hallucinations, and religious delusions. He required hospitalization and was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Following multiple hospitalizations over 5 years, he moved in with his mother, who was granted guardianship.

His mother said Mr. F’s religious delusions were of purity and cleansing the soul. He spent hours memorizing the Bible and would go for days without eating but would drink large amounts of water. She said she thought this was due to his desire to flush out imperfections.

In the past 3 years, Mr. F has been hospitalized several times for severe hyponatremia. At home, his mother attempted to restrict his water intake. However, Mr. F would still drink out of sinks and hoses. Mr. F’s mother reports that over the past month he had become more isolated. He would spend entire days reading the Bible, and his water intake had further increased.

Prior medication trials for Mr. F included haloperidol, up to 10 mg twice per day; aripiprazole, up to 20 mg/d; and risperidone, up to 6 mg nightly. These had been effective, but Mr. F had difficulty with adherence. He did not receive a long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic initially due to lack of access at the rural clinic where he was treated, and later due to his mother’s preference for her son to receive oral medications. Prior to his current presentation, Mr. F’s medication regimen was olanzapine, 10 mg twice a day; perphenazine, 8 mg twice a day; and long-acting propranolol, 60 mg/d. Mr. F had no other chronic medical problems.

EVALUATION Hyponatremia, but why?

Mr. F is intubated and admitted to the surgical service for stabilization due to injuries from his fall. He has fractures of his right sinus and bilateral nasal bones, which are managed nonoperatively. He is delirious, with waxing and waning attention, memory disturbances, and disorientation. His psychotropic medications are held.

Continue to: Imaging of his head...

Imaging of his head does not reveal acute abnormalities suggesting a malignant or paraneoplastic process, and there are no concerns for ongoing seizures. An infection workup is negative. His urine toxicology is negative and blood alcohol level is 0. His sodium normalizes after 3 days of IV fluids and fluid restriction. Therefore, further tests to differentiate the causes of hyponatremia, such as urine electrolytes and urine osmolality, are not pursued.

[polldaddy:10910406]

The authors’ observations

The differential diagnosis for hyponatremia is broad in the setting of psychiatric illness. Low sodium levels could be due to psychotropic medications, psychiatrically-driven behaviors, or an underlying medical problem. Our differential diagnosis for Mr. F included iatrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), diabetes insipidus, or psychogenic polydipsia, a form of primary polydipsia. Other causes of primary polydipsia are related to substances, such as heavy beer intakeor use of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, also known as “ecstasy”), or brain lesions,1 but these causes were less likely given Mr. F’s negative urine toxicology and head imaging.

While psychogenic polydipsia is due to increased water consumption, both SIADH and diabetes insipidus are due to alterations in fluid homeostasis.2,3 Table 12-4 outlines distinguishing characteristics of SIADH, diabetes insipidus, and psychogenic polydipsia. Urine studies were not pursued because Mr. F’s sodium resolved and acute concerns, such as malignancy or infection, were ruled out. Mr. F’s hyponatremia was presumed to be due to psychogenic polydipsia because of his increased fluid intake and normalization of sodium with hypertonic fluids and subsequent fluid restriction. During this time, he was managed on the surgical service; the plan was to pursue urine studies and possibly a fluid challenge if his hyponatremia persisted.

EVALUATION Delirium resolves, delusions persist

While Mr. F is on the surgical service, the treatment team focuses on stabilizing his sodium level and assessing for causes of altered mental status that led to his fall. Psychiatry is consulted for management of his agitation. Following the gradual correction of his sodium level and extubation, his sensorium improves. By hospital Day 5, Mr. F’s delirium resolves.

During this time, Mr. F’s disorganization and religious delusions become apparent. He spends much of his time reading his Bible. He has poor hygiene and limited engagement in activities of daily living. Due to his psychosis and inability to care for himself, Mr. F is transferred to the psychiatric unit with consent from his mother.

Continue to: TREATMENT Olanzapine and fluid restriction

TREATMENT Olanzapine and fluid restriction

In the psychiatric unit, Mr. F is restarted on olanzapine, but not on perphenazine due to anticholinergic effects and not on propranolol due to continued orthostatic hypotension. Five days later, he is at his baseline level of functioning with residual psychosis. His fluid intake is restricted to <1.5 L per day and he is easily compliant.

Mr. F’s mother is comfortable with his discharge home on a regimen of olanzapine, 25 mg/d, and the team discusses the fluid restrictions with her. The treatment team suggests initiating an LAI before Mr. F is discharged, but this is not pursued because his mother thinks he is doing well with the oral medication. She wants to monitor him with the medication changes in the clinic before pursuing an LAI; however, she is open to it in the future.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 20% of patients with schizophrenia may experience psychogenic polydipsia.4,5 The cause of psychogenic polydipsia in patients with serious mental illness is multifactorial. It may stem from malfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, which leads to alterations in antidiuretic hormone secretion and function.4-6

Mr. F’s case highlights several challenges associated with treating psychogenic polydipsia in patients with serious mental illness. Antipsychotics with high dopamine affinity, such as risperidone and haloperidol, may increase the risk of psychogenic polydipsia, while antipsychotics with lower dopamine affinity, such as clozapine, may decrease the occurrence.5 Antipsychotics block postsynaptic dopamine receptors, which can induce supersensitivity by increasing presynaptic dopamine release in the hypothalamic areas, where thirst regulation occurs. This increase in dopamine leads to increased thirst drive and fluid intake.3

Quetiapine or clozapine may have been a better antipsychotic choice because these agents have lower D2 receptor affinity, whereas olanzapine has intermediate binding to D2 receptors.6,7 However, quetiapine and clozapine are more strongly associated with orthostasis, which was a concern during Mr. F’s hospitalization. The weekly laboratory testing required with clozapine use would have been an unfeasible burden for Mr. F because he lived in a rural environment. Perphenazine was not continued due to higher D2 affinity and anticholinergic effects, which can increase thirst.6

Continue to: In addition to switching...

In addition to switching to an antipsychotic with looser D2 binding, other medications for treating polydipsia have been studied. It is hypothesized that the alpha-2 adrenergic system may play a role in thirst regulation. For example, mianserin, an alpha-2 antagonist, may decrease water intake. However, studies have been small and inconsistent.8,9 Propranolol,10 a beta adrenergic receptor blocker; irbesartan,11 an angiotensin-II receptor blocker; demeclocycline,12 a tetracycline that inhibits antidiuretic hormone action; and naltrexone,9 a mu opioid antagonist, have been studied with inconclusive results and a variety of adverse effects5,7,13 (Table 28-13).

Behavioral interventions for patients with psychogenic polydipsia include fluid restriction, twice-daily weight checks, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and reinforcement schedules, which may be useful but less realistic due to need for increased supervision.11,12 Patient and family education on the signs of hyponatremia are important to prevent serious complications, such as those Mr. F experienced.

OUTCOME Repeated hospitalizations

Mr. F is discharged with follow-up in our psychiatry clinic and attends 1 appointment. At that time, his mother reports that Mr. F is compliant with his medication and has limited fluid intake. However, over the next 2 months, he is admitted to our psychiatric unit twice with similar presentations. Each time, the treatment team has extensive discussions with Mr. F’s mother about strategies to limit his water intake and the possibility of residential placement due to his need for a higher level of care. Although she acknowledges that nursing home placement may be needed in the future, she is not ready to take this step.

Three months later, Mr. F returns to our hospital with severe abdominal pain and is found to have a perforated bowel obstruction. His sodium is within normal limits on presentation, and the psychiatry team is not involved during this hospitalization. Mr. F is treated for sepsis and undergoes 3 exploratory laparotomies with continued decline in his health. He dies during this hospitalization. The cause of Mr. F’s perforated bowel obstruction is not determined, and his family does not pursue an autopsy.

The authors’ observations

At Mr. F’s final hospital presentation, his sodium was normal. It is possible Mr. F and his mother had found an acceptable fluid restriction routine, and he may have been doing better from a psychiatric perspective, but this will remain unknown.

Continue to: This case highlights...

This case highlights the clinical and ethical complexity of treating patients with psychogenic polydipsia. Because Mr. F no longer had autonomy, we had to determine if his mother was acting in his best interest as his guardian. Guardianship requirements and expectations vary by state. In our state of Missouri, a guardian is appointed by the court to act in the best interest of the ward, and may be a family member (preferred) or state-appointed. The guardian is responsible for providing the ward’s care and is in charge of financial and medical decisions. In Missouri, the guardian must assure the ward resides in the “least restrictive setting reasonably available,” which is the minimum necessary to provide the ward safe care and housing.14 Full guardianship, as in Mr. F’s case, is different from limited guardianship, which is an option in states such as Missouri. In limited guardianship, the court decides the extent of the guardian’s role in decisions for the ward.14,15

Mr. F’s mother believed she was acting in her son’s best interest by having him home with his family. She believed by living at home, he would derive more enjoyment from life than living in a nursing home. By the time Mr. F presented to our hospital, he had been living with decompensated schizophrenia for years, so some level of psychosis was likely to persist, even with treatment. Given his increasingly frequent hospitalizations for hyponatremia due to increased water intake, more intense supervision may have been needed to maintain his safety, in line with nonmaleficence. The treatment team considered Mr. F’s best interest when discussing placement and worked to understand his mother’s preferences.

His mother continued to acknowledge the need for changes and adjustments at home. She was receptive to the need for fluid restriction and increased structure at home. Therefore, we felt she continued to be acting in his best interest, and his home would be the least restrictive setting for his care. If Mr. F had continued to require repeated hospitalizations and had not passed away, we would have pursued an ethics consult to discuss the need for nursing home placement and how to best approach this with Mr. F’s mother.

Bottom Line

Patients with serious mental illness who present with hyponatremia should be evaluated for psychogenic polydipsia by assessing their dietary and fluid intakes, along with collateral from family. The use of antipsychotics with high dopamine affinity may increase the risk of psychogenic polydipsia. Behavioral interventions include fluid restriction, weight checks, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and reinforcement schedules.

Related Resources

- Sharp CS, Wilson MP. Hyponatremia. In: Nordstrom KD, Wilson MP, eds. Quick guide to psychiatric emergencies. Springer International Publishing; 2018:115-119. doi:10.1007/ 978-3-319-58260-3_21

- Sailer C, Winzeler B, Christ-Crain M. Primary polydipsia in the medical and psychiatric patient: characteristics, complications and therapy. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14514. doi:10.4414/ smw.2017.14514

Drug Brand Names

Amiloride • Midamor

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Demeclocycline • Declomycin

Desmopressin • DDAVP

Haloperidol • Haldol

Irbesartan • Avapro

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Losartan • Cozaar

Mianserin • Tolvon

Naloxone • Narcan

Naltrexone • Revia

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Perphenazine • Trilafon

Propranolol • Inderal LA

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperda

CASE Unresponsive after a presumed seizure

Mr. F, age 44, has schizophrenia. He is brought to the hospital by ambulance after he is found on the ground outside of his mother’s house following a presumed seizure and fall. On arrival to the emergency department, he is unresponsive. His laboratory values are significant for a sodium level of 110 mEq/L (reference range: 135 to 145 mEq/L), indicating hyponatremia.

HISTORY Fixated on purity

Mr. F’s mother reports that Mr. F had an unremarkable childhood. He was raised in a household with both parents and a younger sister. Mr. F did well academically and studied engineering and physics in college. There was no reported history of trauma or substance use.

During his senior year of college, Mr. F began experiencing paranoia, auditory hallucinations, and religious delusions. He required hospitalization and was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Following multiple hospitalizations over 5 years, he moved in with his mother, who was granted guardianship.

His mother said Mr. F’s religious delusions were of purity and cleansing the soul. He spent hours memorizing the Bible and would go for days without eating but would drink large amounts of water. She said she thought this was due to his desire to flush out imperfections.

In the past 3 years, Mr. F has been hospitalized several times for severe hyponatremia. At home, his mother attempted to restrict his water intake. However, Mr. F would still drink out of sinks and hoses. Mr. F’s mother reports that over the past month he had become more isolated. He would spend entire days reading the Bible, and his water intake had further increased.

Prior medication trials for Mr. F included haloperidol, up to 10 mg twice per day; aripiprazole, up to 20 mg/d; and risperidone, up to 6 mg nightly. These had been effective, but Mr. F had difficulty with adherence. He did not receive a long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic initially due to lack of access at the rural clinic where he was treated, and later due to his mother’s preference for her son to receive oral medications. Prior to his current presentation, Mr. F’s medication regimen was olanzapine, 10 mg twice a day; perphenazine, 8 mg twice a day; and long-acting propranolol, 60 mg/d. Mr. F had no other chronic medical problems.

EVALUATION Hyponatremia, but why?

Mr. F is intubated and admitted to the surgical service for stabilization due to injuries from his fall. He has fractures of his right sinus and bilateral nasal bones, which are managed nonoperatively. He is delirious, with waxing and waning attention, memory disturbances, and disorientation. His psychotropic medications are held.

Continue to: Imaging of his head...

Imaging of his head does not reveal acute abnormalities suggesting a malignant or paraneoplastic process, and there are no concerns for ongoing seizures. An infection workup is negative. His urine toxicology is negative and blood alcohol level is 0. His sodium normalizes after 3 days of IV fluids and fluid restriction. Therefore, further tests to differentiate the causes of hyponatremia, such as urine electrolytes and urine osmolality, are not pursued.

[polldaddy:10910406]

The authors’ observations

The differential diagnosis for hyponatremia is broad in the setting of psychiatric illness. Low sodium levels could be due to psychotropic medications, psychiatrically-driven behaviors, or an underlying medical problem. Our differential diagnosis for Mr. F included iatrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), diabetes insipidus, or psychogenic polydipsia, a form of primary polydipsia. Other causes of primary polydipsia are related to substances, such as heavy beer intakeor use of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, also known as “ecstasy”), or brain lesions,1 but these causes were less likely given Mr. F’s negative urine toxicology and head imaging.

While psychogenic polydipsia is due to increased water consumption, both SIADH and diabetes insipidus are due to alterations in fluid homeostasis.2,3 Table 12-4 outlines distinguishing characteristics of SIADH, diabetes insipidus, and psychogenic polydipsia. Urine studies were not pursued because Mr. F’s sodium resolved and acute concerns, such as malignancy or infection, were ruled out. Mr. F’s hyponatremia was presumed to be due to psychogenic polydipsia because of his increased fluid intake and normalization of sodium with hypertonic fluids and subsequent fluid restriction. During this time, he was managed on the surgical service; the plan was to pursue urine studies and possibly a fluid challenge if his hyponatremia persisted.

EVALUATION Delirium resolves, delusions persist

While Mr. F is on the surgical service, the treatment team focuses on stabilizing his sodium level and assessing for causes of altered mental status that led to his fall. Psychiatry is consulted for management of his agitation. Following the gradual correction of his sodium level and extubation, his sensorium improves. By hospital Day 5, Mr. F’s delirium resolves.

During this time, Mr. F’s disorganization and religious delusions become apparent. He spends much of his time reading his Bible. He has poor hygiene and limited engagement in activities of daily living. Due to his psychosis and inability to care for himself, Mr. F is transferred to the psychiatric unit with consent from his mother.

Continue to: TREATMENT Olanzapine and fluid restriction

TREATMENT Olanzapine and fluid restriction

In the psychiatric unit, Mr. F is restarted on olanzapine, but not on perphenazine due to anticholinergic effects and not on propranolol due to continued orthostatic hypotension. Five days later, he is at his baseline level of functioning with residual psychosis. His fluid intake is restricted to <1.5 L per day and he is easily compliant.

Mr. F’s mother is comfortable with his discharge home on a regimen of olanzapine, 25 mg/d, and the team discusses the fluid restrictions with her. The treatment team suggests initiating an LAI before Mr. F is discharged, but this is not pursued because his mother thinks he is doing well with the oral medication. She wants to monitor him with the medication changes in the clinic before pursuing an LAI; however, she is open to it in the future.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 20% of patients with schizophrenia may experience psychogenic polydipsia.4,5 The cause of psychogenic polydipsia in patients with serious mental illness is multifactorial. It may stem from malfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, which leads to alterations in antidiuretic hormone secretion and function.4-6

Mr. F’s case highlights several challenges associated with treating psychogenic polydipsia in patients with serious mental illness. Antipsychotics with high dopamine affinity, such as risperidone and haloperidol, may increase the risk of psychogenic polydipsia, while antipsychotics with lower dopamine affinity, such as clozapine, may decrease the occurrence.5 Antipsychotics block postsynaptic dopamine receptors, which can induce supersensitivity by increasing presynaptic dopamine release in the hypothalamic areas, where thirst regulation occurs. This increase in dopamine leads to increased thirst drive and fluid intake.3

Quetiapine or clozapine may have been a better antipsychotic choice because these agents have lower D2 receptor affinity, whereas olanzapine has intermediate binding to D2 receptors.6,7 However, quetiapine and clozapine are more strongly associated with orthostasis, which was a concern during Mr. F’s hospitalization. The weekly laboratory testing required with clozapine use would have been an unfeasible burden for Mr. F because he lived in a rural environment. Perphenazine was not continued due to higher D2 affinity and anticholinergic effects, which can increase thirst.6

Continue to: In addition to switching...

In addition to switching to an antipsychotic with looser D2 binding, other medications for treating polydipsia have been studied. It is hypothesized that the alpha-2 adrenergic system may play a role in thirst regulation. For example, mianserin, an alpha-2 antagonist, may decrease water intake. However, studies have been small and inconsistent.8,9 Propranolol,10 a beta adrenergic receptor blocker; irbesartan,11 an angiotensin-II receptor blocker; demeclocycline,12 a tetracycline that inhibits antidiuretic hormone action; and naltrexone,9 a mu opioid antagonist, have been studied with inconclusive results and a variety of adverse effects5,7,13 (Table 28-13).

Behavioral interventions for patients with psychogenic polydipsia include fluid restriction, twice-daily weight checks, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and reinforcement schedules, which may be useful but less realistic due to need for increased supervision.11,12 Patient and family education on the signs of hyponatremia are important to prevent serious complications, such as those Mr. F experienced.

OUTCOME Repeated hospitalizations

Mr. F is discharged with follow-up in our psychiatry clinic and attends 1 appointment. At that time, his mother reports that Mr. F is compliant with his medication and has limited fluid intake. However, over the next 2 months, he is admitted to our psychiatric unit twice with similar presentations. Each time, the treatment team has extensive discussions with Mr. F’s mother about strategies to limit his water intake and the possibility of residential placement due to his need for a higher level of care. Although she acknowledges that nursing home placement may be needed in the future, she is not ready to take this step.

Three months later, Mr. F returns to our hospital with severe abdominal pain and is found to have a perforated bowel obstruction. His sodium is within normal limits on presentation, and the psychiatry team is not involved during this hospitalization. Mr. F is treated for sepsis and undergoes 3 exploratory laparotomies with continued decline in his health. He dies during this hospitalization. The cause of Mr. F’s perforated bowel obstruction is not determined, and his family does not pursue an autopsy.

The authors’ observations

At Mr. F’s final hospital presentation, his sodium was normal. It is possible Mr. F and his mother had found an acceptable fluid restriction routine, and he may have been doing better from a psychiatric perspective, but this will remain unknown.

Continue to: This case highlights...

This case highlights the clinical and ethical complexity of treating patients with psychogenic polydipsia. Because Mr. F no longer had autonomy, we had to determine if his mother was acting in his best interest as his guardian. Guardianship requirements and expectations vary by state. In our state of Missouri, a guardian is appointed by the court to act in the best interest of the ward, and may be a family member (preferred) or state-appointed. The guardian is responsible for providing the ward’s care and is in charge of financial and medical decisions. In Missouri, the guardian must assure the ward resides in the “least restrictive setting reasonably available,” which is the minimum necessary to provide the ward safe care and housing.14 Full guardianship, as in Mr. F’s case, is different from limited guardianship, which is an option in states such as Missouri. In limited guardianship, the court decides the extent of the guardian’s role in decisions for the ward.14,15