User login

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) and bipolar disorder are frequently confused with each other, in part because of their considerable symptomatic overlap. This redundancy occurs despite the different ways these disorders are conceptualized: BPD as a personality disorder and bipolar disorder as a brain disease among Axis I clinical disorders.

BPD and bipolar disorder—especially bipolar II—often co-occur ( Box ) and are frequently misidentified, as shown by clinical and epidemiologic studies. Misdiagnosis creates problems for clinicians and patients. When diagnosed with BPD, patients with bipolar disorder may be deprived of potentially effective pharmacologic treatments.1 Conversely, the stigma that BPD carries—particularly in the mental health community—may lead clinicians to:

- not even disclose the BPD diagnosis to patients2

- lean in the direction of diagnosing BPD as bipolar disorder, potentially resulting in treatments that have little relevance or failure to refer for more appropriate psychosocial treatments.

To help you avoid confusion and the pitfalls of misdiagnosis, this article clarifies the distinctions between bipolar disorder and BPD. We discuss symptom overlap, highlight key differences between the constructs, outline diagnostic differences, and provide useful suggestions to discern the differential diagnosis.

between BPD and bipolar disorder*

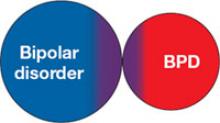

1. Inability of current nosology to separate 2 distinct conditions

Relatively indistinct diagnostic boundaries confuse the differentiation of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and bipolar disorder (5 of 9 BPD criteria may occur with mania or hypomania). In this model, the person has 1 disorder but because of symptom overlap receives a diagnosis of both. Because structured interviews do not allow for subjective judgment or expert opinion, the result is the generation of 2 diagnoses when 1 may provide a more parsimonious and valid explanation.

2. BPD exists on a spectrum with bipolar disorder

The mood lability of BPD may be viewed as not unlike that seen with bipolar disorder.1 Behaviors displayed by patients with BPD are subsequently conceptualized as arising from their unstable mood. Supporting arguments cite family study data and evidence from pharmacotherapy trials of anticonvulsants, including divalproex, for rapid cycling bipolar disorder and BPD.2 Family studies have been notable for their failure to directly characterize family members, however, and clinical trials have been quite small. Further, treatment response may have very limited nosologic implications.

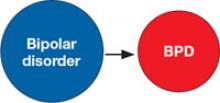

3. Bipolar disorder is a risk factor for BPD

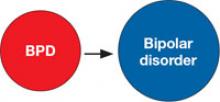

4. BPD is a risk factor for bipolar disorder

Early emergence of a bipolar disorder (in preadolescent or adolescent patients) has been proposed to disrupt psychological development, leading to BPD. This adverse impact on personality development—the “scar hypothesis”3 —is supported by data showing greater risk of co-occurring BPD with earlier onset bipolar disorder.4 More important, prospective studies of patients with bipolar disorder show a greater risk for developing BPD.5

BPD also may be a risk factor for the development of bipolar disorder—the “vulnerability hypothesis.”3 Patients with BPD are more likely to develop bipolar disorder, even compared to patients with other personality disorders.5

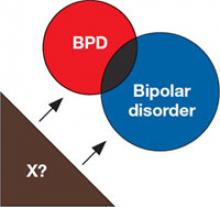

5. Shared risk factors

BPD and bipolar disorder may be linked by shared risk factors, such as shared genes or trait neuroticism.3

*Some evidence supports each potential explanation, and they are not necessarily mutually exclusive

References

a. Akiskal HS. Demystifying borderline personality: critique of the concept and unorthodox reflections on its natural kinship with the bipolar spectrum. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(6):401-407.

b. Mackinnon DF, Pies R. Affective instability as rapid cycling: theoretical and clinical implications for borderline personality and bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(1):1-14.

c. Christensen MV, Kessing LV. Do personality traits predict first onset in depressive and bipolar disorder? Nord J Psychiatry. 2006;60(2):79-88.

d. Goldberg JF, Garno JL. Age at onset of bipolar disorder and risk for comorbid borderline personality disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(2):205-208.

e. Gunderson JG, Weinberg I, Daversa MT, et al. Descriptive and longitudinal observations on the relationship of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1173-1178.

Overlapping symptoms

Bipolar disorder is generally considered a clinical disorder or brain disease that can be understood as a broken mood “thermostat.” The lifetime prevalence of bipolar types I and II is approximately 2%.3 Approximately one-half of patients have a family history of illness, and multiple genes are believed to influence inheritance. Mania is the disorder’s hallmark,4 although overactivity has alternatively been proposed as a core feature.5 Most patients with mania ultimately experience depression6 ( Table 1 ).

No dimensional personality correlates have been consistently demonstrated in bipolar disorder, although co-occurring personality disorders—often the “dramatic” Cluster B type—are common4,7 and may adversely affect treatment response and suicide risk.8,9

Both bipolar disorder and BPD are associated with considerable risk of suicide or suicide attempts.10,11 Self-mutilation or self-injurious behavior without suicidal intent are particularly common in BPD.12 Threats of suicide—which may be manipulative or help-seeking—also are common in BPD and tend to be acute rather than chronic.13

Borderline personality disorder is characterized by an enduring and inflexible pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that impairs an individual’s psychosocial or vocational function. Its estimated prevalence is approximately 1%,14 although recent community estimates approach 6%.15 Genetic influences play a lesser etiologic role in BPD than in bipolar disorder.

Several of BPD’s common features ( Table 2 )—impulsivity, mood instability, inappropriate anger, suicidal behavior, and unstable relationships—are shared with bipolar disorder, but patients with BPD tend to show higher levels of impulsiveness and hostility than patients with bipolar disorder.16 Dimensional assessments of personality traits suggest that BPD is characterized by high neuroticism and low agreeableness.17 BPD also has been more strongly associated with a childhood history of abuse, even when compared with control groups having other personality disorders or major depression.18 The male-to-female ratio for bipolar disorder approximates 1:1;3 in BPD this ratio has been estimated at 1:4 in clinical samples19 and near 1:1 in community samples.15

BPD and bipolar disorder often co-occur. Evidence indicates ≤20% of patients with BPD have comorbid bipolar disorder20 and 15% of patients with bipolar disorder have comorbid BPD.21 Co-occurrence happens much more often than would be expected by chance. These similar bidirectional comorbidity estimates (15% to 20%) would not be expected for conditions of such differing prevalence (<1% vs 2% or more). This suggests:

- the estimated prevalence of bipolar disorder in BPD is too low

- the estimated prevalence of BPD in bipolar disorder samples is too high

- borderline personality disorder is present in >1% of the population

- bipolar disorder is less common

- some combination of the above.

Among these possibilities, the prevalence estimates of bipolar disorder are the most consistent. Several studies suggest that BPD may be much more common, with some estimates exceeding 5%.15

Table 1

Common signs and symptoms

associated with mania and depression in bipolar disorder

| (Hypo)mania | Depression |

|---|---|

| Elevated mood | Decreased mood |

| Irritability | Irritability |

| Decreased need for sleep | Anhedonia |

| Grandiosity | Decreased self-attitude |

| Talkativeness | Insomnia/hypersomnia |

| Racing thoughts | Change in appetite/weight |

| Increased motor activity | Fatigue |

| Increased sex drive | Hopelessness |

| Religiosity | Suicidal thoughts |

| Distractibility | Impaired concentration |

Table 2

Borderline personality disorder: Commonly reported features

| Impulsivity |

| Unstable relationships |

| Unstable self-image |

| Affective instability |

| Fear of abandonment |

| Recurrent self-injurious or suicidal behavior |

| Feelings of emptiness |

| Intense anger or hostility |

| Transient paranoia or dissociative symptoms |

Roots of misdiagnosis

The presence of bipolar disorder or BPD may increase the risk that the other will be misdiagnosed. When symptoms of both are present, those suggesting 1 diagnosis may reflect the consequences of the other. A diagnosis of BPD could represent a partially treated or treatment-resistant bipolar disorder, or a BPD diagnosis could be the result of several years of disruption by a mood disorder.

Characteristics of bipolar disorder have contributed to clinician bias in favor of that diagnosis rather than BPD ( Table 3 ).22,23 Bipolar disorder also may be misdiagnosed as BPD. This error may most likely occur when the history focuses excessively on cross-sectional symptoms, such as when a patient with bipolar disorder shows prominent mood lability or interpersonal sensitivity during a mood episode but not when euthymic.

Bipolar II disorder. The confusion between bipolar disorder and BPD may be particularly problematic for patients with bipolar II disorder or subthreshold bipolar disorders. The manias of bipolar I disorder are much more readily distinguishable from the mood instability or reactivity of BPD. The manic symptoms of bipolar I are more florid, more pronounced, and lead to more obvious impairment.

The milder highs of bipolar II may resemble the mood fluctuations seen in BPD. Further, bipolar II is characterized by a greater chronicity and affective morbidity than bipolar I, and episodes of illness may be characterized by irritability, anger, and racing thoughts.24 Whereas impulsivity or aggression are more characteristic of BPD, bipolar II is similar to BPD on dimensions of affective instability.24,25

When present in BPD, affective instability or lability is conceptualized as ultra-rapid or ultradian, with a frequency of hours to days. BPD is less likely than bipolar II to show affective lability between depression and euthymia or elation and more likely to show fluctuations into anger and anxiety.26

Nonetheless, because of the increased prominence of shared features and reduced distinguishing features, bipolar II and BPD are prone to misdiagnosis and commonly co-occur.

Table 3

Clinician biases that may favor a bipolar disorder diagnosis, rather than BPD

| Bipolar disorder is supported by decades of research |

| Patients with bipolar disorder are often considered more “likeable” than those with BPD |

| Bipolar disorder is more treatable and has a better long-term outcome than BPD (although BPD is generally characterized by clinical improvement, whereas bipolar disorder is more stable with perhaps some increase in depressive symptom burden) |

| Widely thought to have a biologic basis, the bipolar diagnosis conveys less stigma than BPD, which often is less empathically attributed to the patient’s own failings |

| A bipolar diagnosis is easier to explain to patients than BPD; many psychiatrists have difficulty explaining personality disorders in terms patients understand |

| BPD: borderline personality disorder |

| Source: References 22,23 |

History, the diagnostic key

A thorough and rigorous psychiatric history is essential to distinguish BPD from bipolar disorder. Supplementing the patient’s history with an informant interview is often helpful.

Because personality disorders are considered a chronic and enduring pattern of maladaptive behavior, focus the history on longitudinal course and not simply cross-sectional symptoms. Thus, symptoms suggestive of BPD that are confined only to clearly defined episodes of mood disturbance and are absent during euthymia would not warrant a BPD diagnosis.

Temporal relationship. A detailed chronologic history can help determine the temporal relationship between any borderline features and mood episodes. When the patient’s life story is used as a scaffold for the phenomenologic portions of the psychiatric history, one can determine whether any such functional impairment is confined to episodes of mood disorder or appears as an enduring pattern of thinking, acting, and relating. Exploring what happened at notable life transitions—leaving school, loss of job, divorce/separation—may be similarly helpful.

Family history of psychiatric illness may provide a clue to an individual’s genetic predisposition but, of course, does not determine diagnosis. A detailed family and social history that provides evidence of an individual’s function in school, work, and interpersonal relationships is more relevant.

Abandonment and identity issues. Essential to BPD is fear of abandonment, often an undue fear that those important to patients will leave them. Patients may go to extremes to avoid being “abandoned,” even when this threat is not genuine.27,28 Their insecure attachments often lead them to fear being alone. The patient with BPD may:

- make frantic phone calls or send text messages to a friend or lover seeking reassurance

- take extreme measures such as refusing to leave the person’s home or pleading with them not to leave.

Patients with BPD often struggle with identity disturbance, leading them to wonder who they are and what their beliefs and core values are.29 Although occasionally patients with bipolar disorder may have these symptoms, they are not characteristic of bipolar disorder.

Mood lability. The time course of changes in affect or mood swings also may help distinguish BPD from bipolar disorder.

- With bipolar disorder the shift typically is from depression to elation or the reverse, and moods are sustained. Manias or hypomanias are often immediately followed by a “crash” into depression.

- With BPD, “roller-coaster moods” are typical, mood shifts are nonsustained, and the poles often are anxiety, anger, or desperation.

Patients with BPD often report moods shifting rapidly over minutes or hours, but they rarely describe moods sustained for days or weeks on end—other than perhaps depression. Mood lability of BPD often is produced by interpersonal sensitivity, whereas mood lability in bipolar disorder tends to be autonomous and persistent.

Young patients. Assessment can be particularly challenging in young adults and adolescents because symptoms of an emerging bipolar disorder can be more difficult to distinguish from BPD.30 Patients this young also may have less longitudinal history to distinguish an enduring pattern of thinking and relating from a mood disorder. For these cases, it may be particularly important to classify the frequency and pattern of mood symptoms.

Affective dysregulation is a core feature of BPD and is variably defined as a mood reactivity, typically of short duration (often hours). Cycling in bipolar disorder classically involves a periodicity of weeks to months. Even the broadest definitions include a minimum duration of 2 days for hypomania.5

Mood reactivity can occur within episodes of bipolar disorder, although episodes may occur spontaneously and without an obvious precipitant or stressor. Impulsivity may represent more of an essential feature of BPD than affective instability or mood reactivity and may be of particular diagnostic relevance.

Treatment implications

When you are unable to make a clear diagnosis, describe your clinical reasoning and differential diagnosis in the assessment or formulation. With close follow-up, the longitudinal history and course of illness may eventually lead you to an accurate diagnosis.

There are good reasons to acknowledge both conditions when bipolar disorder and BPD are present. Proper recognition of bipolar disorder is a prerequisite to taking full advantage of proven pharmacologic treatments. The evidence base for pharmacologic management of BPD remains limited,31 but recognizing this disorder may help the patient understand his or her psychiatric history and encourage the use of effective psychosocial treatments.

Psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder may target demoralization and circadian rhythms with sleep hygiene or social rhythms therapy. Acknowledging BPD:

- helps both clinician and patient to better understand the condition

- facilitates setting realistic treatment goals because BPD tends to respond to medication less robustly than bipolar disorder.

Recognizing BPD also allows for referral to targeted psychosocial treatments, including dialectical behavior therapy, mentalization-based treatment, or Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS).32-34

Related resources

- National Institute of Mental Health. Overview on borderline personality disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/borderline-personality-disorder-fact-sheet/index.shtml.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder/index.shtml.

- Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS). www.uihealthcare.com/topics/medicaldepartments/psychiatry/stepps/index.html.

Drug brand name

- Divalproex • Depakote, Depakene, others

Disclosures

Dr. Fiedorowicz reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Black receives research/grant support from AstraZeneca and Forest Laboratories and is a consultant to Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Nancee Blum, MSW, and Nancy Hale, RN, for their assistance and expertise in the preparation of this article.

1. John H, Sharma V. Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder as borderline personality disorder: clinical and economic consequences. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007;1-4[epub ahead of print].

2. Lequesne ER, Hersh RG. Disclosure of a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(3):170-176.

3. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543-552.

4. Belmaker RH. Bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(5):476-486.

5. Benazzi F. Testing new diagnostic criteria for hypomania. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):99-104.

6. Solomon DA, Leon AC, Endicott J, et al. Unipolar mania over the course of a 20-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):2049-2051.

7. Schiavone P, Dorz S, Conforti D, et al. Comorbidity of DSM-IV personality disorders in unipolar and bipolar affective disorders: a comparative study. Psychol Rep. 2004;95(1):121-128.

8. Fan AH, Hassell J. Bipolar disorder and comorbid personality psychopathology: a review of the literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(11):1794-1803.

9. Garno JL, Goldberg JF, Ramirez PM, et al. Bipolar disorder with comorbid cluster B personality disorder features: impact on suicidality. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(3):339-345.

10. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(3):226-239.

11. Fiedorowicz JG, Leon AC, Keller MB, et al. Do risk factors for suicidal behavior differ by affective disorder polarity? Psychol Med. 2009;39(5):763-771.

12. Paris J. Understanding self-mutilation in borderline personality disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):179-185.

13. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al. The McLean Study of Adult Development (MSAD): overview and implications of the first six years of prospective follow-up. J Pers Disord. 2005;19(5):505-523.

14. Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):590-596.

15. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533-545.

16. Wilson ST, Stanley B, Oquendo MA, et al. Comparing impulsiveness, hostility, and depression in borderline personality disorder and bipolar II disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(10):1533-1539.

17. Zweig-Frank H, Paris J. The five-factor model of personality in borderline and nonborderline personality disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 1995;40(9):523-526.

18. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Adult experiences of abuse reported by borderline patients and Axis II comparison subjects over six years of prospective follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(6):412-416.

19. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Violence in the lives of adult borderline patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(2):65-71.

20. McCormick B, Blum N, Hansel R, et al. Relationship of sex to symptom severity, psychiatric comorbidity, and health care utilization in 163 subjects with borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(5):406-412.

21. Brieger P, Ehrt U, Marneros A. Frequency of comorbid personality disorders in bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44(1):28-34.

22. Paris J, Zweig-Frank H. A 27-year follow-up of patients with borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(6):482-487.

23. Coryell WH, Fiedorowicz JG, Solomon D, et al. Age transitions in the course of bipolar I disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39(8):1247-1252.

24. Benazzi F. Borderline personality-bipolar spectrum relationship. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(1):68-74.

25. Critchfield KL, Levy KN, Clarkin JF. The relationship between impulsivity, aggression, and impulsive-aggression in borderline personality disorder: an empirical analysis of self-report measures. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(6):555-570.

26. Henry C, Mitropoulou V, New AS, et al. Affective instability and impulsivity in borderline personality and bipolar II disorders: similarities and differences. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35(6):307-312.

27. Bray A. The extended mind and borderline personality disorder. Australas Psychiatry. 2008;16(1):8-12.

28. Gunderson JG. The borderline patient’s intolerance of aloneness: insecure attachments and therapist availability. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(6):752-758.

29. Jorgensen CR. Disturbed sense of identity in borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2006;20(6):618-644.

30. Smith DJ, Muir WJ, Blackwood DH. Borderline personality disorder characteristics in young adults with recurrent mood disorders: a comparison of bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(1):17-23.

31. Binks CA, Fenton M, McCarthy L, et al. Pharmacological interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(1);CD005653.-

32. Lynch TR, Trost WT, Salsman N, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:181-205.

33. Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(1):36-51.

34. Blum N, St John D, Pfohl B, et al. Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial and 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):468-478.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) and bipolar disorder are frequently confused with each other, in part because of their considerable symptomatic overlap. This redundancy occurs despite the different ways these disorders are conceptualized: BPD as a personality disorder and bipolar disorder as a brain disease among Axis I clinical disorders.

BPD and bipolar disorder—especially bipolar II—often co-occur ( Box ) and are frequently misidentified, as shown by clinical and epidemiologic studies. Misdiagnosis creates problems for clinicians and patients. When diagnosed with BPD, patients with bipolar disorder may be deprived of potentially effective pharmacologic treatments.1 Conversely, the stigma that BPD carries—particularly in the mental health community—may lead clinicians to:

- not even disclose the BPD diagnosis to patients2

- lean in the direction of diagnosing BPD as bipolar disorder, potentially resulting in treatments that have little relevance or failure to refer for more appropriate psychosocial treatments.

To help you avoid confusion and the pitfalls of misdiagnosis, this article clarifies the distinctions between bipolar disorder and BPD. We discuss symptom overlap, highlight key differences between the constructs, outline diagnostic differences, and provide useful suggestions to discern the differential diagnosis.

between BPD and bipolar disorder*

1. Inability of current nosology to separate 2 distinct conditions

Relatively indistinct diagnostic boundaries confuse the differentiation of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and bipolar disorder (5 of 9 BPD criteria may occur with mania or hypomania). In this model, the person has 1 disorder but because of symptom overlap receives a diagnosis of both. Because structured interviews do not allow for subjective judgment or expert opinion, the result is the generation of 2 diagnoses when 1 may provide a more parsimonious and valid explanation.

2. BPD exists on a spectrum with bipolar disorder

The mood lability of BPD may be viewed as not unlike that seen with bipolar disorder.1 Behaviors displayed by patients with BPD are subsequently conceptualized as arising from their unstable mood. Supporting arguments cite family study data and evidence from pharmacotherapy trials of anticonvulsants, including divalproex, for rapid cycling bipolar disorder and BPD.2 Family studies have been notable for their failure to directly characterize family members, however, and clinical trials have been quite small. Further, treatment response may have very limited nosologic implications.

3. Bipolar disorder is a risk factor for BPD

4. BPD is a risk factor for bipolar disorder

Early emergence of a bipolar disorder (in preadolescent or adolescent patients) has been proposed to disrupt psychological development, leading to BPD. This adverse impact on personality development—the “scar hypothesis”3 —is supported by data showing greater risk of co-occurring BPD with earlier onset bipolar disorder.4 More important, prospective studies of patients with bipolar disorder show a greater risk for developing BPD.5

BPD also may be a risk factor for the development of bipolar disorder—the “vulnerability hypothesis.”3 Patients with BPD are more likely to develop bipolar disorder, even compared to patients with other personality disorders.5

5. Shared risk factors

BPD and bipolar disorder may be linked by shared risk factors, such as shared genes or trait neuroticism.3

*Some evidence supports each potential explanation, and they are not necessarily mutually exclusive

References

a. Akiskal HS. Demystifying borderline personality: critique of the concept and unorthodox reflections on its natural kinship with the bipolar spectrum. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(6):401-407.

b. Mackinnon DF, Pies R. Affective instability as rapid cycling: theoretical and clinical implications for borderline personality and bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(1):1-14.

c. Christensen MV, Kessing LV. Do personality traits predict first onset in depressive and bipolar disorder? Nord J Psychiatry. 2006;60(2):79-88.

d. Goldberg JF, Garno JL. Age at onset of bipolar disorder and risk for comorbid borderline personality disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(2):205-208.

e. Gunderson JG, Weinberg I, Daversa MT, et al. Descriptive and longitudinal observations on the relationship of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1173-1178.

Overlapping symptoms

Bipolar disorder is generally considered a clinical disorder or brain disease that can be understood as a broken mood “thermostat.” The lifetime prevalence of bipolar types I and II is approximately 2%.3 Approximately one-half of patients have a family history of illness, and multiple genes are believed to influence inheritance. Mania is the disorder’s hallmark,4 although overactivity has alternatively been proposed as a core feature.5 Most patients with mania ultimately experience depression6 ( Table 1 ).

No dimensional personality correlates have been consistently demonstrated in bipolar disorder, although co-occurring personality disorders—often the “dramatic” Cluster B type—are common4,7 and may adversely affect treatment response and suicide risk.8,9

Both bipolar disorder and BPD are associated with considerable risk of suicide or suicide attempts.10,11 Self-mutilation or self-injurious behavior without suicidal intent are particularly common in BPD.12 Threats of suicide—which may be manipulative or help-seeking—also are common in BPD and tend to be acute rather than chronic.13

Borderline personality disorder is characterized by an enduring and inflexible pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that impairs an individual’s psychosocial or vocational function. Its estimated prevalence is approximately 1%,14 although recent community estimates approach 6%.15 Genetic influences play a lesser etiologic role in BPD than in bipolar disorder.

Several of BPD’s common features ( Table 2 )—impulsivity, mood instability, inappropriate anger, suicidal behavior, and unstable relationships—are shared with bipolar disorder, but patients with BPD tend to show higher levels of impulsiveness and hostility than patients with bipolar disorder.16 Dimensional assessments of personality traits suggest that BPD is characterized by high neuroticism and low agreeableness.17 BPD also has been more strongly associated with a childhood history of abuse, even when compared with control groups having other personality disorders or major depression.18 The male-to-female ratio for bipolar disorder approximates 1:1;3 in BPD this ratio has been estimated at 1:4 in clinical samples19 and near 1:1 in community samples.15

BPD and bipolar disorder often co-occur. Evidence indicates ≤20% of patients with BPD have comorbid bipolar disorder20 and 15% of patients with bipolar disorder have comorbid BPD.21 Co-occurrence happens much more often than would be expected by chance. These similar bidirectional comorbidity estimates (15% to 20%) would not be expected for conditions of such differing prevalence (<1% vs 2% or more). This suggests:

- the estimated prevalence of bipolar disorder in BPD is too low

- the estimated prevalence of BPD in bipolar disorder samples is too high

- borderline personality disorder is present in >1% of the population

- bipolar disorder is less common

- some combination of the above.

Among these possibilities, the prevalence estimates of bipolar disorder are the most consistent. Several studies suggest that BPD may be much more common, with some estimates exceeding 5%.15

Table 1

Common signs and symptoms

associated with mania and depression in bipolar disorder

| (Hypo)mania | Depression |

|---|---|

| Elevated mood | Decreased mood |

| Irritability | Irritability |

| Decreased need for sleep | Anhedonia |

| Grandiosity | Decreased self-attitude |

| Talkativeness | Insomnia/hypersomnia |

| Racing thoughts | Change in appetite/weight |

| Increased motor activity | Fatigue |

| Increased sex drive | Hopelessness |

| Religiosity | Suicidal thoughts |

| Distractibility | Impaired concentration |

Table 2

Borderline personality disorder: Commonly reported features

| Impulsivity |

| Unstable relationships |

| Unstable self-image |

| Affective instability |

| Fear of abandonment |

| Recurrent self-injurious or suicidal behavior |

| Feelings of emptiness |

| Intense anger or hostility |

| Transient paranoia or dissociative symptoms |

Roots of misdiagnosis

The presence of bipolar disorder or BPD may increase the risk that the other will be misdiagnosed. When symptoms of both are present, those suggesting 1 diagnosis may reflect the consequences of the other. A diagnosis of BPD could represent a partially treated or treatment-resistant bipolar disorder, or a BPD diagnosis could be the result of several years of disruption by a mood disorder.

Characteristics of bipolar disorder have contributed to clinician bias in favor of that diagnosis rather than BPD ( Table 3 ).22,23 Bipolar disorder also may be misdiagnosed as BPD. This error may most likely occur when the history focuses excessively on cross-sectional symptoms, such as when a patient with bipolar disorder shows prominent mood lability or interpersonal sensitivity during a mood episode but not when euthymic.

Bipolar II disorder. The confusion between bipolar disorder and BPD may be particularly problematic for patients with bipolar II disorder or subthreshold bipolar disorders. The manias of bipolar I disorder are much more readily distinguishable from the mood instability or reactivity of BPD. The manic symptoms of bipolar I are more florid, more pronounced, and lead to more obvious impairment.

The milder highs of bipolar II may resemble the mood fluctuations seen in BPD. Further, bipolar II is characterized by a greater chronicity and affective morbidity than bipolar I, and episodes of illness may be characterized by irritability, anger, and racing thoughts.24 Whereas impulsivity or aggression are more characteristic of BPD, bipolar II is similar to BPD on dimensions of affective instability.24,25

When present in BPD, affective instability or lability is conceptualized as ultra-rapid or ultradian, with a frequency of hours to days. BPD is less likely than bipolar II to show affective lability between depression and euthymia or elation and more likely to show fluctuations into anger and anxiety.26

Nonetheless, because of the increased prominence of shared features and reduced distinguishing features, bipolar II and BPD are prone to misdiagnosis and commonly co-occur.

Table 3

Clinician biases that may favor a bipolar disorder diagnosis, rather than BPD

| Bipolar disorder is supported by decades of research |

| Patients with bipolar disorder are often considered more “likeable” than those with BPD |

| Bipolar disorder is more treatable and has a better long-term outcome than BPD (although BPD is generally characterized by clinical improvement, whereas bipolar disorder is more stable with perhaps some increase in depressive symptom burden) |

| Widely thought to have a biologic basis, the bipolar diagnosis conveys less stigma than BPD, which often is less empathically attributed to the patient’s own failings |

| A bipolar diagnosis is easier to explain to patients than BPD; many psychiatrists have difficulty explaining personality disorders in terms patients understand |

| BPD: borderline personality disorder |

| Source: References 22,23 |

History, the diagnostic key

A thorough and rigorous psychiatric history is essential to distinguish BPD from bipolar disorder. Supplementing the patient’s history with an informant interview is often helpful.

Because personality disorders are considered a chronic and enduring pattern of maladaptive behavior, focus the history on longitudinal course and not simply cross-sectional symptoms. Thus, symptoms suggestive of BPD that are confined only to clearly defined episodes of mood disturbance and are absent during euthymia would not warrant a BPD diagnosis.

Temporal relationship. A detailed chronologic history can help determine the temporal relationship between any borderline features and mood episodes. When the patient’s life story is used as a scaffold for the phenomenologic portions of the psychiatric history, one can determine whether any such functional impairment is confined to episodes of mood disorder or appears as an enduring pattern of thinking, acting, and relating. Exploring what happened at notable life transitions—leaving school, loss of job, divorce/separation—may be similarly helpful.

Family history of psychiatric illness may provide a clue to an individual’s genetic predisposition but, of course, does not determine diagnosis. A detailed family and social history that provides evidence of an individual’s function in school, work, and interpersonal relationships is more relevant.

Abandonment and identity issues. Essential to BPD is fear of abandonment, often an undue fear that those important to patients will leave them. Patients may go to extremes to avoid being “abandoned,” even when this threat is not genuine.27,28 Their insecure attachments often lead them to fear being alone. The patient with BPD may:

- make frantic phone calls or send text messages to a friend or lover seeking reassurance

- take extreme measures such as refusing to leave the person’s home or pleading with them not to leave.

Patients with BPD often struggle with identity disturbance, leading them to wonder who they are and what their beliefs and core values are.29 Although occasionally patients with bipolar disorder may have these symptoms, they are not characteristic of bipolar disorder.

Mood lability. The time course of changes in affect or mood swings also may help distinguish BPD from bipolar disorder.

- With bipolar disorder the shift typically is from depression to elation or the reverse, and moods are sustained. Manias or hypomanias are often immediately followed by a “crash” into depression.

- With BPD, “roller-coaster moods” are typical, mood shifts are nonsustained, and the poles often are anxiety, anger, or desperation.

Patients with BPD often report moods shifting rapidly over minutes or hours, but they rarely describe moods sustained for days or weeks on end—other than perhaps depression. Mood lability of BPD often is produced by interpersonal sensitivity, whereas mood lability in bipolar disorder tends to be autonomous and persistent.

Young patients. Assessment can be particularly challenging in young adults and adolescents because symptoms of an emerging bipolar disorder can be more difficult to distinguish from BPD.30 Patients this young also may have less longitudinal history to distinguish an enduring pattern of thinking and relating from a mood disorder. For these cases, it may be particularly important to classify the frequency and pattern of mood symptoms.

Affective dysregulation is a core feature of BPD and is variably defined as a mood reactivity, typically of short duration (often hours). Cycling in bipolar disorder classically involves a periodicity of weeks to months. Even the broadest definitions include a minimum duration of 2 days for hypomania.5

Mood reactivity can occur within episodes of bipolar disorder, although episodes may occur spontaneously and without an obvious precipitant or stressor. Impulsivity may represent more of an essential feature of BPD than affective instability or mood reactivity and may be of particular diagnostic relevance.

Treatment implications

When you are unable to make a clear diagnosis, describe your clinical reasoning and differential diagnosis in the assessment or formulation. With close follow-up, the longitudinal history and course of illness may eventually lead you to an accurate diagnosis.

There are good reasons to acknowledge both conditions when bipolar disorder and BPD are present. Proper recognition of bipolar disorder is a prerequisite to taking full advantage of proven pharmacologic treatments. The evidence base for pharmacologic management of BPD remains limited,31 but recognizing this disorder may help the patient understand his or her psychiatric history and encourage the use of effective psychosocial treatments.

Psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder may target demoralization and circadian rhythms with sleep hygiene or social rhythms therapy. Acknowledging BPD:

- helps both clinician and patient to better understand the condition

- facilitates setting realistic treatment goals because BPD tends to respond to medication less robustly than bipolar disorder.

Recognizing BPD also allows for referral to targeted psychosocial treatments, including dialectical behavior therapy, mentalization-based treatment, or Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS).32-34

Related resources

- National Institute of Mental Health. Overview on borderline personality disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/borderline-personality-disorder-fact-sheet/index.shtml.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder/index.shtml.

- Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS). www.uihealthcare.com/topics/medicaldepartments/psychiatry/stepps/index.html.

Drug brand name

- Divalproex • Depakote, Depakene, others

Disclosures

Dr. Fiedorowicz reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Black receives research/grant support from AstraZeneca and Forest Laboratories and is a consultant to Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Nancee Blum, MSW, and Nancy Hale, RN, for their assistance and expertise in the preparation of this article.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) and bipolar disorder are frequently confused with each other, in part because of their considerable symptomatic overlap. This redundancy occurs despite the different ways these disorders are conceptualized: BPD as a personality disorder and bipolar disorder as a brain disease among Axis I clinical disorders.

BPD and bipolar disorder—especially bipolar II—often co-occur ( Box ) and are frequently misidentified, as shown by clinical and epidemiologic studies. Misdiagnosis creates problems for clinicians and patients. When diagnosed with BPD, patients with bipolar disorder may be deprived of potentially effective pharmacologic treatments.1 Conversely, the stigma that BPD carries—particularly in the mental health community—may lead clinicians to:

- not even disclose the BPD diagnosis to patients2

- lean in the direction of diagnosing BPD as bipolar disorder, potentially resulting in treatments that have little relevance or failure to refer for more appropriate psychosocial treatments.

To help you avoid confusion and the pitfalls of misdiagnosis, this article clarifies the distinctions between bipolar disorder and BPD. We discuss symptom overlap, highlight key differences between the constructs, outline diagnostic differences, and provide useful suggestions to discern the differential diagnosis.

between BPD and bipolar disorder*

1. Inability of current nosology to separate 2 distinct conditions

Relatively indistinct diagnostic boundaries confuse the differentiation of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and bipolar disorder (5 of 9 BPD criteria may occur with mania or hypomania). In this model, the person has 1 disorder but because of symptom overlap receives a diagnosis of both. Because structured interviews do not allow for subjective judgment or expert opinion, the result is the generation of 2 diagnoses when 1 may provide a more parsimonious and valid explanation.

2. BPD exists on a spectrum with bipolar disorder

The mood lability of BPD may be viewed as not unlike that seen with bipolar disorder.1 Behaviors displayed by patients with BPD are subsequently conceptualized as arising from their unstable mood. Supporting arguments cite family study data and evidence from pharmacotherapy trials of anticonvulsants, including divalproex, for rapid cycling bipolar disorder and BPD.2 Family studies have been notable for their failure to directly characterize family members, however, and clinical trials have been quite small. Further, treatment response may have very limited nosologic implications.

3. Bipolar disorder is a risk factor for BPD

4. BPD is a risk factor for bipolar disorder

Early emergence of a bipolar disorder (in preadolescent or adolescent patients) has been proposed to disrupt psychological development, leading to BPD. This adverse impact on personality development—the “scar hypothesis”3 —is supported by data showing greater risk of co-occurring BPD with earlier onset bipolar disorder.4 More important, prospective studies of patients with bipolar disorder show a greater risk for developing BPD.5

BPD also may be a risk factor for the development of bipolar disorder—the “vulnerability hypothesis.”3 Patients with BPD are more likely to develop bipolar disorder, even compared to patients with other personality disorders.5

5. Shared risk factors

BPD and bipolar disorder may be linked by shared risk factors, such as shared genes or trait neuroticism.3

*Some evidence supports each potential explanation, and they are not necessarily mutually exclusive

References

a. Akiskal HS. Demystifying borderline personality: critique of the concept and unorthodox reflections on its natural kinship with the bipolar spectrum. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(6):401-407.

b. Mackinnon DF, Pies R. Affective instability as rapid cycling: theoretical and clinical implications for borderline personality and bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(1):1-14.

c. Christensen MV, Kessing LV. Do personality traits predict first onset in depressive and bipolar disorder? Nord J Psychiatry. 2006;60(2):79-88.

d. Goldberg JF, Garno JL. Age at onset of bipolar disorder and risk for comorbid borderline personality disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(2):205-208.

e. Gunderson JG, Weinberg I, Daversa MT, et al. Descriptive and longitudinal observations on the relationship of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1173-1178.

Overlapping symptoms

Bipolar disorder is generally considered a clinical disorder or brain disease that can be understood as a broken mood “thermostat.” The lifetime prevalence of bipolar types I and II is approximately 2%.3 Approximately one-half of patients have a family history of illness, and multiple genes are believed to influence inheritance. Mania is the disorder’s hallmark,4 although overactivity has alternatively been proposed as a core feature.5 Most patients with mania ultimately experience depression6 ( Table 1 ).

No dimensional personality correlates have been consistently demonstrated in bipolar disorder, although co-occurring personality disorders—often the “dramatic” Cluster B type—are common4,7 and may adversely affect treatment response and suicide risk.8,9

Both bipolar disorder and BPD are associated with considerable risk of suicide or suicide attempts.10,11 Self-mutilation or self-injurious behavior without suicidal intent are particularly common in BPD.12 Threats of suicide—which may be manipulative or help-seeking—also are common in BPD and tend to be acute rather than chronic.13

Borderline personality disorder is characterized by an enduring and inflexible pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that impairs an individual’s psychosocial or vocational function. Its estimated prevalence is approximately 1%,14 although recent community estimates approach 6%.15 Genetic influences play a lesser etiologic role in BPD than in bipolar disorder.

Several of BPD’s common features ( Table 2 )—impulsivity, mood instability, inappropriate anger, suicidal behavior, and unstable relationships—are shared with bipolar disorder, but patients with BPD tend to show higher levels of impulsiveness and hostility than patients with bipolar disorder.16 Dimensional assessments of personality traits suggest that BPD is characterized by high neuroticism and low agreeableness.17 BPD also has been more strongly associated with a childhood history of abuse, even when compared with control groups having other personality disorders or major depression.18 The male-to-female ratio for bipolar disorder approximates 1:1;3 in BPD this ratio has been estimated at 1:4 in clinical samples19 and near 1:1 in community samples.15

BPD and bipolar disorder often co-occur. Evidence indicates ≤20% of patients with BPD have comorbid bipolar disorder20 and 15% of patients with bipolar disorder have comorbid BPD.21 Co-occurrence happens much more often than would be expected by chance. These similar bidirectional comorbidity estimates (15% to 20%) would not be expected for conditions of such differing prevalence (<1% vs 2% or more). This suggests:

- the estimated prevalence of bipolar disorder in BPD is too low

- the estimated prevalence of BPD in bipolar disorder samples is too high

- borderline personality disorder is present in >1% of the population

- bipolar disorder is less common

- some combination of the above.

Among these possibilities, the prevalence estimates of bipolar disorder are the most consistent. Several studies suggest that BPD may be much more common, with some estimates exceeding 5%.15

Table 1

Common signs and symptoms

associated with mania and depression in bipolar disorder

| (Hypo)mania | Depression |

|---|---|

| Elevated mood | Decreased mood |

| Irritability | Irritability |

| Decreased need for sleep | Anhedonia |

| Grandiosity | Decreased self-attitude |

| Talkativeness | Insomnia/hypersomnia |

| Racing thoughts | Change in appetite/weight |

| Increased motor activity | Fatigue |

| Increased sex drive | Hopelessness |

| Religiosity | Suicidal thoughts |

| Distractibility | Impaired concentration |

Table 2

Borderline personality disorder: Commonly reported features

| Impulsivity |

| Unstable relationships |

| Unstable self-image |

| Affective instability |

| Fear of abandonment |

| Recurrent self-injurious or suicidal behavior |

| Feelings of emptiness |

| Intense anger or hostility |

| Transient paranoia or dissociative symptoms |

Roots of misdiagnosis

The presence of bipolar disorder or BPD may increase the risk that the other will be misdiagnosed. When symptoms of both are present, those suggesting 1 diagnosis may reflect the consequences of the other. A diagnosis of BPD could represent a partially treated or treatment-resistant bipolar disorder, or a BPD diagnosis could be the result of several years of disruption by a mood disorder.

Characteristics of bipolar disorder have contributed to clinician bias in favor of that diagnosis rather than BPD ( Table 3 ).22,23 Bipolar disorder also may be misdiagnosed as BPD. This error may most likely occur when the history focuses excessively on cross-sectional symptoms, such as when a patient with bipolar disorder shows prominent mood lability or interpersonal sensitivity during a mood episode but not when euthymic.

Bipolar II disorder. The confusion between bipolar disorder and BPD may be particularly problematic for patients with bipolar II disorder or subthreshold bipolar disorders. The manias of bipolar I disorder are much more readily distinguishable from the mood instability or reactivity of BPD. The manic symptoms of bipolar I are more florid, more pronounced, and lead to more obvious impairment.

The milder highs of bipolar II may resemble the mood fluctuations seen in BPD. Further, bipolar II is characterized by a greater chronicity and affective morbidity than bipolar I, and episodes of illness may be characterized by irritability, anger, and racing thoughts.24 Whereas impulsivity or aggression are more characteristic of BPD, bipolar II is similar to BPD on dimensions of affective instability.24,25

When present in BPD, affective instability or lability is conceptualized as ultra-rapid or ultradian, with a frequency of hours to days. BPD is less likely than bipolar II to show affective lability between depression and euthymia or elation and more likely to show fluctuations into anger and anxiety.26

Nonetheless, because of the increased prominence of shared features and reduced distinguishing features, bipolar II and BPD are prone to misdiagnosis and commonly co-occur.

Table 3

Clinician biases that may favor a bipolar disorder diagnosis, rather than BPD

| Bipolar disorder is supported by decades of research |

| Patients with bipolar disorder are often considered more “likeable” than those with BPD |

| Bipolar disorder is more treatable and has a better long-term outcome than BPD (although BPD is generally characterized by clinical improvement, whereas bipolar disorder is more stable with perhaps some increase in depressive symptom burden) |

| Widely thought to have a biologic basis, the bipolar diagnosis conveys less stigma than BPD, which often is less empathically attributed to the patient’s own failings |

| A bipolar diagnosis is easier to explain to patients than BPD; many psychiatrists have difficulty explaining personality disorders in terms patients understand |

| BPD: borderline personality disorder |

| Source: References 22,23 |

History, the diagnostic key

A thorough and rigorous psychiatric history is essential to distinguish BPD from bipolar disorder. Supplementing the patient’s history with an informant interview is often helpful.

Because personality disorders are considered a chronic and enduring pattern of maladaptive behavior, focus the history on longitudinal course and not simply cross-sectional symptoms. Thus, symptoms suggestive of BPD that are confined only to clearly defined episodes of mood disturbance and are absent during euthymia would not warrant a BPD diagnosis.

Temporal relationship. A detailed chronologic history can help determine the temporal relationship between any borderline features and mood episodes. When the patient’s life story is used as a scaffold for the phenomenologic portions of the psychiatric history, one can determine whether any such functional impairment is confined to episodes of mood disorder or appears as an enduring pattern of thinking, acting, and relating. Exploring what happened at notable life transitions—leaving school, loss of job, divorce/separation—may be similarly helpful.

Family history of psychiatric illness may provide a clue to an individual’s genetic predisposition but, of course, does not determine diagnosis. A detailed family and social history that provides evidence of an individual’s function in school, work, and interpersonal relationships is more relevant.

Abandonment and identity issues. Essential to BPD is fear of abandonment, often an undue fear that those important to patients will leave them. Patients may go to extremes to avoid being “abandoned,” even when this threat is not genuine.27,28 Their insecure attachments often lead them to fear being alone. The patient with BPD may:

- make frantic phone calls or send text messages to a friend or lover seeking reassurance

- take extreme measures such as refusing to leave the person’s home or pleading with them not to leave.

Patients with BPD often struggle with identity disturbance, leading them to wonder who they are and what their beliefs and core values are.29 Although occasionally patients with bipolar disorder may have these symptoms, they are not characteristic of bipolar disorder.

Mood lability. The time course of changes in affect or mood swings also may help distinguish BPD from bipolar disorder.

- With bipolar disorder the shift typically is from depression to elation or the reverse, and moods are sustained. Manias or hypomanias are often immediately followed by a “crash” into depression.

- With BPD, “roller-coaster moods” are typical, mood shifts are nonsustained, and the poles often are anxiety, anger, or desperation.

Patients with BPD often report moods shifting rapidly over minutes or hours, but they rarely describe moods sustained for days or weeks on end—other than perhaps depression. Mood lability of BPD often is produced by interpersonal sensitivity, whereas mood lability in bipolar disorder tends to be autonomous and persistent.

Young patients. Assessment can be particularly challenging in young adults and adolescents because symptoms of an emerging bipolar disorder can be more difficult to distinguish from BPD.30 Patients this young also may have less longitudinal history to distinguish an enduring pattern of thinking and relating from a mood disorder. For these cases, it may be particularly important to classify the frequency and pattern of mood symptoms.

Affective dysregulation is a core feature of BPD and is variably defined as a mood reactivity, typically of short duration (often hours). Cycling in bipolar disorder classically involves a periodicity of weeks to months. Even the broadest definitions include a minimum duration of 2 days for hypomania.5

Mood reactivity can occur within episodes of bipolar disorder, although episodes may occur spontaneously and without an obvious precipitant or stressor. Impulsivity may represent more of an essential feature of BPD than affective instability or mood reactivity and may be of particular diagnostic relevance.

Treatment implications

When you are unable to make a clear diagnosis, describe your clinical reasoning and differential diagnosis in the assessment or formulation. With close follow-up, the longitudinal history and course of illness may eventually lead you to an accurate diagnosis.

There are good reasons to acknowledge both conditions when bipolar disorder and BPD are present. Proper recognition of bipolar disorder is a prerequisite to taking full advantage of proven pharmacologic treatments. The evidence base for pharmacologic management of BPD remains limited,31 but recognizing this disorder may help the patient understand his or her psychiatric history and encourage the use of effective psychosocial treatments.

Psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder may target demoralization and circadian rhythms with sleep hygiene or social rhythms therapy. Acknowledging BPD:

- helps both clinician and patient to better understand the condition

- facilitates setting realistic treatment goals because BPD tends to respond to medication less robustly than bipolar disorder.

Recognizing BPD also allows for referral to targeted psychosocial treatments, including dialectical behavior therapy, mentalization-based treatment, or Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS).32-34

Related resources

- National Institute of Mental Health. Overview on borderline personality disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/borderline-personality-disorder-fact-sheet/index.shtml.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder/index.shtml.

- Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS). www.uihealthcare.com/topics/medicaldepartments/psychiatry/stepps/index.html.

Drug brand name

- Divalproex • Depakote, Depakene, others

Disclosures

Dr. Fiedorowicz reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Black receives research/grant support from AstraZeneca and Forest Laboratories and is a consultant to Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Nancee Blum, MSW, and Nancy Hale, RN, for their assistance and expertise in the preparation of this article.

1. John H, Sharma V. Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder as borderline personality disorder: clinical and economic consequences. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007;1-4[epub ahead of print].

2. Lequesne ER, Hersh RG. Disclosure of a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(3):170-176.

3. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543-552.

4. Belmaker RH. Bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(5):476-486.

5. Benazzi F. Testing new diagnostic criteria for hypomania. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):99-104.

6. Solomon DA, Leon AC, Endicott J, et al. Unipolar mania over the course of a 20-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):2049-2051.

7. Schiavone P, Dorz S, Conforti D, et al. Comorbidity of DSM-IV personality disorders in unipolar and bipolar affective disorders: a comparative study. Psychol Rep. 2004;95(1):121-128.

8. Fan AH, Hassell J. Bipolar disorder and comorbid personality psychopathology: a review of the literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(11):1794-1803.

9. Garno JL, Goldberg JF, Ramirez PM, et al. Bipolar disorder with comorbid cluster B personality disorder features: impact on suicidality. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(3):339-345.

10. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(3):226-239.

11. Fiedorowicz JG, Leon AC, Keller MB, et al. Do risk factors for suicidal behavior differ by affective disorder polarity? Psychol Med. 2009;39(5):763-771.

12. Paris J. Understanding self-mutilation in borderline personality disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):179-185.

13. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al. The McLean Study of Adult Development (MSAD): overview and implications of the first six years of prospective follow-up. J Pers Disord. 2005;19(5):505-523.

14. Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):590-596.

15. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533-545.

16. Wilson ST, Stanley B, Oquendo MA, et al. Comparing impulsiveness, hostility, and depression in borderline personality disorder and bipolar II disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(10):1533-1539.

17. Zweig-Frank H, Paris J. The five-factor model of personality in borderline and nonborderline personality disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 1995;40(9):523-526.

18. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Adult experiences of abuse reported by borderline patients and Axis II comparison subjects over six years of prospective follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(6):412-416.

19. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Violence in the lives of adult borderline patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(2):65-71.

20. McCormick B, Blum N, Hansel R, et al. Relationship of sex to symptom severity, psychiatric comorbidity, and health care utilization in 163 subjects with borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(5):406-412.

21. Brieger P, Ehrt U, Marneros A. Frequency of comorbid personality disorders in bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44(1):28-34.

22. Paris J, Zweig-Frank H. A 27-year follow-up of patients with borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(6):482-487.

23. Coryell WH, Fiedorowicz JG, Solomon D, et al. Age transitions in the course of bipolar I disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39(8):1247-1252.

24. Benazzi F. Borderline personality-bipolar spectrum relationship. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(1):68-74.

25. Critchfield KL, Levy KN, Clarkin JF. The relationship between impulsivity, aggression, and impulsive-aggression in borderline personality disorder: an empirical analysis of self-report measures. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(6):555-570.

26. Henry C, Mitropoulou V, New AS, et al. Affective instability and impulsivity in borderline personality and bipolar II disorders: similarities and differences. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35(6):307-312.

27. Bray A. The extended mind and borderline personality disorder. Australas Psychiatry. 2008;16(1):8-12.

28. Gunderson JG. The borderline patient’s intolerance of aloneness: insecure attachments and therapist availability. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(6):752-758.

29. Jorgensen CR. Disturbed sense of identity in borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2006;20(6):618-644.

30. Smith DJ, Muir WJ, Blackwood DH. Borderline personality disorder characteristics in young adults with recurrent mood disorders: a comparison of bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(1):17-23.

31. Binks CA, Fenton M, McCarthy L, et al. Pharmacological interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(1);CD005653.-

32. Lynch TR, Trost WT, Salsman N, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:181-205.

33. Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(1):36-51.

34. Blum N, St John D, Pfohl B, et al. Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial and 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):468-478.

1. John H, Sharma V. Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder as borderline personality disorder: clinical and economic consequences. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007;1-4[epub ahead of print].

2. Lequesne ER, Hersh RG. Disclosure of a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(3):170-176.

3. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543-552.

4. Belmaker RH. Bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(5):476-486.

5. Benazzi F. Testing new diagnostic criteria for hypomania. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):99-104.

6. Solomon DA, Leon AC, Endicott J, et al. Unipolar mania over the course of a 20-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):2049-2051.

7. Schiavone P, Dorz S, Conforti D, et al. Comorbidity of DSM-IV personality disorders in unipolar and bipolar affective disorders: a comparative study. Psychol Rep. 2004;95(1):121-128.

8. Fan AH, Hassell J. Bipolar disorder and comorbid personality psychopathology: a review of the literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(11):1794-1803.

9. Garno JL, Goldberg JF, Ramirez PM, et al. Bipolar disorder with comorbid cluster B personality disorder features: impact on suicidality. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(3):339-345.

10. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(3):226-239.

11. Fiedorowicz JG, Leon AC, Keller MB, et al. Do risk factors for suicidal behavior differ by affective disorder polarity? Psychol Med. 2009;39(5):763-771.

12. Paris J. Understanding self-mutilation in borderline personality disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):179-185.

13. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al. The McLean Study of Adult Development (MSAD): overview and implications of the first six years of prospective follow-up. J Pers Disord. 2005;19(5):505-523.

14. Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):590-596.

15. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533-545.

16. Wilson ST, Stanley B, Oquendo MA, et al. Comparing impulsiveness, hostility, and depression in borderline personality disorder and bipolar II disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(10):1533-1539.

17. Zweig-Frank H, Paris J. The five-factor model of personality in borderline and nonborderline personality disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 1995;40(9):523-526.

18. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Adult experiences of abuse reported by borderline patients and Axis II comparison subjects over six years of prospective follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(6):412-416.

19. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Violence in the lives of adult borderline patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(2):65-71.

20. McCormick B, Blum N, Hansel R, et al. Relationship of sex to symptom severity, psychiatric comorbidity, and health care utilization in 163 subjects with borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(5):406-412.

21. Brieger P, Ehrt U, Marneros A. Frequency of comorbid personality disorders in bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44(1):28-34.

22. Paris J, Zweig-Frank H. A 27-year follow-up of patients with borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(6):482-487.

23. Coryell WH, Fiedorowicz JG, Solomon D, et al. Age transitions in the course of bipolar I disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39(8):1247-1252.

24. Benazzi F. Borderline personality-bipolar spectrum relationship. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(1):68-74.

25. Critchfield KL, Levy KN, Clarkin JF. The relationship between impulsivity, aggression, and impulsive-aggression in borderline personality disorder: an empirical analysis of self-report measures. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(6):555-570.

26. Henry C, Mitropoulou V, New AS, et al. Affective instability and impulsivity in borderline personality and bipolar II disorders: similarities and differences. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35(6):307-312.

27. Bray A. The extended mind and borderline personality disorder. Australas Psychiatry. 2008;16(1):8-12.

28. Gunderson JG. The borderline patient’s intolerance of aloneness: insecure attachments and therapist availability. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(6):752-758.

29. Jorgensen CR. Disturbed sense of identity in borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2006;20(6):618-644.

30. Smith DJ, Muir WJ, Blackwood DH. Borderline personality disorder characteristics in young adults with recurrent mood disorders: a comparison of bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(1):17-23.

31. Binks CA, Fenton M, McCarthy L, et al. Pharmacological interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(1);CD005653.-

32. Lynch TR, Trost WT, Salsman N, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:181-205.

33. Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(1):36-51.

34. Blum N, St John D, Pfohl B, et al. Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial and 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):468-478.