User login

Bullying, intimidation, verbal abuse—these behaviors negatively affect self-esteem, feelings of competence, and workplace morale. And they can devastate hospital professionals and their patients.

When 2,095 healthcare providers (1,565 nurses, 354 pharmacists, and 176 others) responded to an Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) survey on intimidation in their healthcare setting, remarkable data were collected.1

Perhaps the most alarming statistic in the 2003-2004 study was that 7% of respondents (n=147) reported they had been involved in a medication error allowed to occur partly because the respondents were afraid to question the prescriber’s decision. At a large urban trauma center in the northeastern United States, nurses listed intimidation as one of the barriers to implementing a sharps safety program.2

Nurses’ Perceptions

Research over the past decade has spotlighted intimidation in healthcare.3

“Bullying and harassment still happen in many areas of medicine,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, hospitalist and director, Inpatient Service, Division of General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. “The question is, how do you monitor yourself to make sure you aren’t falling into that hierarchical frame of mind that could intervene in great teaching and learning and great patient care?”

Dr. Pressel and his partner, David I. Rappaport, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at duPont, have focused on the literature pertaining to nurse-physician relationships. Research shows that intimidation impedes nurse recruitment, retention, and satisfaction. In one study, 90% of nurses reported experiencing at least one episode of verbal abuse.4 A 1997 study examining the effects of intimidation on 35 pediatric nurses over a three-month period found that 25 (71.4%) of them reported being yelled at or loudly admonished. Sixteen (45.7%) had been victims of insults. Thirty (85.7%) were spoken to in a condescending manner. One-third of nurses believed that such behavior was “part of the job.”

Although studies have differed as to the most common source of this abuse—patients and families or physicians—a study of pediatric nurses reported a similar incidence from both sources.5 And, nurses are often guilty of verbally abusing each other.6

When the duPont pediatric hospitalist team began performing more family-centered rounds, they began to appreciate the nurse-physician relationship. “We have worked hard to have a charge nurse and oftentimes the bedside nurse with us when we round,” Dr. Rappaport says. Speculating that rounding with hospitalists allowed nurses to feel more part of the team, Dr. Rappaport says know the medical plan, consolidate efforts such that pages to residents were reduced, and generally improve communication. They heard from participating nurses that it made a tremendous difference. This prompted them to conduct their research.

“Our study looked at the nurse-physician relationship globally, not intimidation or abuse specifically,” says Dr. Rappaport. Along with their nurse colleague Norine Watson, RN, Drs. Pressel and Rappaport are examining the relationship between nurses and different categories of physicians: how nurses perceive interactions between nurses and surgical residents, surgical attendings, community physicians, pediatric residents, and pediatric hospitalists.

“Early data suggest that hospitalists may work more effectively with nurses because they share many of the same goals,” says Dr. Rappaport. “As hospital leaders, hospitalists can also improve working conditions for nurses by providing more accessible, efficient, and effective care. Presumably, improved collaboration will also include decreased intimidation or abuse from physicians and also probably from dissatisfied patients and families.”

Avoiding the trap of communicating in a manner that is too direct and might be construed as abusive requires self-awareness and the realization that people receive information in different ways, says Dr. Pressel. Standard professional behavior is the key. Beyond that, the challenge is giving feedback constructively and in a positive manner.

“Hospitalists [may be] more in tune with the needs of nurses than nonhospitalists,” says Dr. Rappaport. “I think that is one of our strengths. We need to continue to facilitate very strong relationships between nurses and physicians because without good nursing care, hospitalists simply cannot provide good medical care.”

There is another way hospitalists can help address verbal abuse. “Studies consistently show that nurses are hesitant to report episodes of verbal abuse,” Dr. Rappaport says, “whether it is from a family, a patient, a physician, or a fellow nurse. Fewer than one in five nurses reports these episodes. One thing that hospitalists can do is work with hospital administration to create an environment that is more proactive in addressing these concerns and allowing nurses to feel more support in this area.”

Only 60% of respondents to the ISMP survey felt their organization had clearly defined an effective process for handling disagreements with a medication order’s safety. Only about a third felt the process facilitated their bypassing an intimidating prescriber or their own supervisor if necessary. Although 70% of respondents reported that they thought their organization or manager would support them if they reported intimidating behavior, only 39% of respondents believed their organization was dealing effectively with intimidating behavior.

Untapped Source

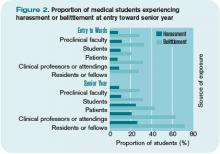

Perceptions of intimidation also occur among trainees. When 2,884 students from the class of 2003 at 16 U.S. medical schools completed questionnaires at various times during training, 27% reported having been “harassed” by house staff, 21% by faculty, and 25% by patients.7 Further, 71% reported having been “belittled” by house staff, 63% by faculty, and 43% by patients.

Mistreated students were significantly more likely to have suffered stress, be depressed or suicidal, and less likely to report being glad they trained as a physician.

—David I. Rappaport, MD, pediatric hospitalist, Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del.

This may have an underlying effect on the potential to monitor for patient safety.8,9 Because errors and near misses often result from miscommunication, medical students may be adept at preventing certain types of errors. Students’ observation skills may be just as keen, if not more so, than their more clinically proficient healthcare teammates.8 In four cases from two U.S. academic health centers reported by medical students Samuel Seiden, Cynthia Galvan, and Ruth Lamm in 2006, medical students demonstrated keen attention to detail and appropriately characterized problematic situations with patients—adding another layer of defense within systems safeguarding against patient harm.8 Yet of the 76% of medical students who had observed a medical error, only about half of the students reported the errors to a resident or an attending, despite having received patient-safety training; only 7% reported having used an electronic medical error reporting system.10

By Example

Some intimidation in medical education may be the result of anger toward students and residents over a lack of medical knowledge, says Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans and member of the SHM Board of Directors. “It is natural to feel [that anger]; people abhor in others what they most detest in themselves,’’ he says. “As physicians, a lack of medical knowledge is what we detest in ourselves. But a student’s ignorance is usually a product of where she is in her training; that’s why she is with you.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University, New Orleans

Anger alienates students, absolving them of the guilt of not knowing the information, and demotivating them from learning it. “The lesson to be communicated is that it is OK not to know, but it is not OK to continue to not know,” Dr. Wiese says. “Reprimands should be reserved for the student who does not know, and then after being taught or asked to look it up, continues to not know.”

“The average physician who practices for 30 years will take care of roughly 80,000 people,” estimates Dr. Wiese. “That’s an arithmetic contribution and there is nothing wrong with that. But if you really want to change the world, teaching is the rule. The same 30 years invested in teaching will indirectly affect 400 million people,” he says. “Even better, if you can train your students and residents in the value of coaching their students and residents, well, now you’re talking about 10 billion people that you can affect over the course of a career.”

The question to ask yourself, says Dr. Wiese, is: Do you want to change the world? “If you do, this is the way to do it,” he says.

“For the 30 years in your career, focus on clinical coaching and getting others to clinically coach. That way, especially if you have the right motives in your heart, the right vision for the way you want to see the profession practiced, and the way you want patient care performed, that’s your shot at changing the world.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: practitioners speak up about this unresolved problem (Part I). Available at w.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040311_2.asp. Last accessed June 27, 2007.

- Hagstrom AM. Perceived barriers to implementation of a successful sharps safety program. AORN J. 2006;83(2):391-7.

- Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient Safety Qual Healthc. 2006 Jul-Aug;3:16-24.

- Manderino MA, Berkey N. Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13(1):48-55.

- Pejic AR. Verbal abuse: A problem for pediatric nurses. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(4):271-279.

- Rowe MM, Sherlock H. Stress and verbal abuse in nursing: do burned out nurses eat their young? J Nurs Manag. 2005May;13(3):242-248.

- Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, et al. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):682.

- Seiden SC, Galvan C, Lamm R. Role of medical students in preventing patient harm and enhancing patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Aug;15(4):272-276.

- Wood DF. Bullying and harassment in medical schools. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):664-665.

- Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med. 2006 Jan;81(1):94-101.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: Mapping a plan for cultural change in healthcare (Part II). Available at www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040325.asp Last accessed July 2, 2007.

Bullying, intimidation, verbal abuse—these behaviors negatively affect self-esteem, feelings of competence, and workplace morale. And they can devastate hospital professionals and their patients.

When 2,095 healthcare providers (1,565 nurses, 354 pharmacists, and 176 others) responded to an Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) survey on intimidation in their healthcare setting, remarkable data were collected.1

Perhaps the most alarming statistic in the 2003-2004 study was that 7% of respondents (n=147) reported they had been involved in a medication error allowed to occur partly because the respondents were afraid to question the prescriber’s decision. At a large urban trauma center in the northeastern United States, nurses listed intimidation as one of the barriers to implementing a sharps safety program.2

Nurses’ Perceptions

Research over the past decade has spotlighted intimidation in healthcare.3

“Bullying and harassment still happen in many areas of medicine,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, hospitalist and director, Inpatient Service, Division of General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. “The question is, how do you monitor yourself to make sure you aren’t falling into that hierarchical frame of mind that could intervene in great teaching and learning and great patient care?”

Dr. Pressel and his partner, David I. Rappaport, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at duPont, have focused on the literature pertaining to nurse-physician relationships. Research shows that intimidation impedes nurse recruitment, retention, and satisfaction. In one study, 90% of nurses reported experiencing at least one episode of verbal abuse.4 A 1997 study examining the effects of intimidation on 35 pediatric nurses over a three-month period found that 25 (71.4%) of them reported being yelled at or loudly admonished. Sixteen (45.7%) had been victims of insults. Thirty (85.7%) were spoken to in a condescending manner. One-third of nurses believed that such behavior was “part of the job.”

Although studies have differed as to the most common source of this abuse—patients and families or physicians—a study of pediatric nurses reported a similar incidence from both sources.5 And, nurses are often guilty of verbally abusing each other.6

When the duPont pediatric hospitalist team began performing more family-centered rounds, they began to appreciate the nurse-physician relationship. “We have worked hard to have a charge nurse and oftentimes the bedside nurse with us when we round,” Dr. Rappaport says. Speculating that rounding with hospitalists allowed nurses to feel more part of the team, Dr. Rappaport says know the medical plan, consolidate efforts such that pages to residents were reduced, and generally improve communication. They heard from participating nurses that it made a tremendous difference. This prompted them to conduct their research.

“Our study looked at the nurse-physician relationship globally, not intimidation or abuse specifically,” says Dr. Rappaport. Along with their nurse colleague Norine Watson, RN, Drs. Pressel and Rappaport are examining the relationship between nurses and different categories of physicians: how nurses perceive interactions between nurses and surgical residents, surgical attendings, community physicians, pediatric residents, and pediatric hospitalists.

“Early data suggest that hospitalists may work more effectively with nurses because they share many of the same goals,” says Dr. Rappaport. “As hospital leaders, hospitalists can also improve working conditions for nurses by providing more accessible, efficient, and effective care. Presumably, improved collaboration will also include decreased intimidation or abuse from physicians and also probably from dissatisfied patients and families.”

Avoiding the trap of communicating in a manner that is too direct and might be construed as abusive requires self-awareness and the realization that people receive information in different ways, says Dr. Pressel. Standard professional behavior is the key. Beyond that, the challenge is giving feedback constructively and in a positive manner.

“Hospitalists [may be] more in tune with the needs of nurses than nonhospitalists,” says Dr. Rappaport. “I think that is one of our strengths. We need to continue to facilitate very strong relationships between nurses and physicians because without good nursing care, hospitalists simply cannot provide good medical care.”

There is another way hospitalists can help address verbal abuse. “Studies consistently show that nurses are hesitant to report episodes of verbal abuse,” Dr. Rappaport says, “whether it is from a family, a patient, a physician, or a fellow nurse. Fewer than one in five nurses reports these episodes. One thing that hospitalists can do is work with hospital administration to create an environment that is more proactive in addressing these concerns and allowing nurses to feel more support in this area.”

Only 60% of respondents to the ISMP survey felt their organization had clearly defined an effective process for handling disagreements with a medication order’s safety. Only about a third felt the process facilitated their bypassing an intimidating prescriber or their own supervisor if necessary. Although 70% of respondents reported that they thought their organization or manager would support them if they reported intimidating behavior, only 39% of respondents believed their organization was dealing effectively with intimidating behavior.

Untapped Source

Perceptions of intimidation also occur among trainees. When 2,884 students from the class of 2003 at 16 U.S. medical schools completed questionnaires at various times during training, 27% reported having been “harassed” by house staff, 21% by faculty, and 25% by patients.7 Further, 71% reported having been “belittled” by house staff, 63% by faculty, and 43% by patients.

Mistreated students were significantly more likely to have suffered stress, be depressed or suicidal, and less likely to report being glad they trained as a physician.

—David I. Rappaport, MD, pediatric hospitalist, Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del.

This may have an underlying effect on the potential to monitor for patient safety.8,9 Because errors and near misses often result from miscommunication, medical students may be adept at preventing certain types of errors. Students’ observation skills may be just as keen, if not more so, than their more clinically proficient healthcare teammates.8 In four cases from two U.S. academic health centers reported by medical students Samuel Seiden, Cynthia Galvan, and Ruth Lamm in 2006, medical students demonstrated keen attention to detail and appropriately characterized problematic situations with patients—adding another layer of defense within systems safeguarding against patient harm.8 Yet of the 76% of medical students who had observed a medical error, only about half of the students reported the errors to a resident or an attending, despite having received patient-safety training; only 7% reported having used an electronic medical error reporting system.10

By Example

Some intimidation in medical education may be the result of anger toward students and residents over a lack of medical knowledge, says Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans and member of the SHM Board of Directors. “It is natural to feel [that anger]; people abhor in others what they most detest in themselves,’’ he says. “As physicians, a lack of medical knowledge is what we detest in ourselves. But a student’s ignorance is usually a product of where she is in her training; that’s why she is with you.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University, New Orleans

Anger alienates students, absolving them of the guilt of not knowing the information, and demotivating them from learning it. “The lesson to be communicated is that it is OK not to know, but it is not OK to continue to not know,” Dr. Wiese says. “Reprimands should be reserved for the student who does not know, and then after being taught or asked to look it up, continues to not know.”

“The average physician who practices for 30 years will take care of roughly 80,000 people,” estimates Dr. Wiese. “That’s an arithmetic contribution and there is nothing wrong with that. But if you really want to change the world, teaching is the rule. The same 30 years invested in teaching will indirectly affect 400 million people,” he says. “Even better, if you can train your students and residents in the value of coaching their students and residents, well, now you’re talking about 10 billion people that you can affect over the course of a career.”

The question to ask yourself, says Dr. Wiese, is: Do you want to change the world? “If you do, this is the way to do it,” he says.

“For the 30 years in your career, focus on clinical coaching and getting others to clinically coach. That way, especially if you have the right motives in your heart, the right vision for the way you want to see the profession practiced, and the way you want patient care performed, that’s your shot at changing the world.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: practitioners speak up about this unresolved problem (Part I). Available at w.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040311_2.asp. Last accessed June 27, 2007.

- Hagstrom AM. Perceived barriers to implementation of a successful sharps safety program. AORN J. 2006;83(2):391-7.

- Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient Safety Qual Healthc. 2006 Jul-Aug;3:16-24.

- Manderino MA, Berkey N. Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13(1):48-55.

- Pejic AR. Verbal abuse: A problem for pediatric nurses. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(4):271-279.

- Rowe MM, Sherlock H. Stress and verbal abuse in nursing: do burned out nurses eat their young? J Nurs Manag. 2005May;13(3):242-248.

- Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, et al. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):682.

- Seiden SC, Galvan C, Lamm R. Role of medical students in preventing patient harm and enhancing patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Aug;15(4):272-276.

- Wood DF. Bullying and harassment in medical schools. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):664-665.

- Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med. 2006 Jan;81(1):94-101.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: Mapping a plan for cultural change in healthcare (Part II). Available at www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040325.asp Last accessed July 2, 2007.

Bullying, intimidation, verbal abuse—these behaviors negatively affect self-esteem, feelings of competence, and workplace morale. And they can devastate hospital professionals and their patients.

When 2,095 healthcare providers (1,565 nurses, 354 pharmacists, and 176 others) responded to an Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) survey on intimidation in their healthcare setting, remarkable data were collected.1

Perhaps the most alarming statistic in the 2003-2004 study was that 7% of respondents (n=147) reported they had been involved in a medication error allowed to occur partly because the respondents were afraid to question the prescriber’s decision. At a large urban trauma center in the northeastern United States, nurses listed intimidation as one of the barriers to implementing a sharps safety program.2

Nurses’ Perceptions

Research over the past decade has spotlighted intimidation in healthcare.3

“Bullying and harassment still happen in many areas of medicine,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, hospitalist and director, Inpatient Service, Division of General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. “The question is, how do you monitor yourself to make sure you aren’t falling into that hierarchical frame of mind that could intervene in great teaching and learning and great patient care?”

Dr. Pressel and his partner, David I. Rappaport, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at duPont, have focused on the literature pertaining to nurse-physician relationships. Research shows that intimidation impedes nurse recruitment, retention, and satisfaction. In one study, 90% of nurses reported experiencing at least one episode of verbal abuse.4 A 1997 study examining the effects of intimidation on 35 pediatric nurses over a three-month period found that 25 (71.4%) of them reported being yelled at or loudly admonished. Sixteen (45.7%) had been victims of insults. Thirty (85.7%) were spoken to in a condescending manner. One-third of nurses believed that such behavior was “part of the job.”

Although studies have differed as to the most common source of this abuse—patients and families or physicians—a study of pediatric nurses reported a similar incidence from both sources.5 And, nurses are often guilty of verbally abusing each other.6

When the duPont pediatric hospitalist team began performing more family-centered rounds, they began to appreciate the nurse-physician relationship. “We have worked hard to have a charge nurse and oftentimes the bedside nurse with us when we round,” Dr. Rappaport says. Speculating that rounding with hospitalists allowed nurses to feel more part of the team, Dr. Rappaport says know the medical plan, consolidate efforts such that pages to residents were reduced, and generally improve communication. They heard from participating nurses that it made a tremendous difference. This prompted them to conduct their research.

“Our study looked at the nurse-physician relationship globally, not intimidation or abuse specifically,” says Dr. Rappaport. Along with their nurse colleague Norine Watson, RN, Drs. Pressel and Rappaport are examining the relationship between nurses and different categories of physicians: how nurses perceive interactions between nurses and surgical residents, surgical attendings, community physicians, pediatric residents, and pediatric hospitalists.

“Early data suggest that hospitalists may work more effectively with nurses because they share many of the same goals,” says Dr. Rappaport. “As hospital leaders, hospitalists can also improve working conditions for nurses by providing more accessible, efficient, and effective care. Presumably, improved collaboration will also include decreased intimidation or abuse from physicians and also probably from dissatisfied patients and families.”

Avoiding the trap of communicating in a manner that is too direct and might be construed as abusive requires self-awareness and the realization that people receive information in different ways, says Dr. Pressel. Standard professional behavior is the key. Beyond that, the challenge is giving feedback constructively and in a positive manner.

“Hospitalists [may be] more in tune with the needs of nurses than nonhospitalists,” says Dr. Rappaport. “I think that is one of our strengths. We need to continue to facilitate very strong relationships between nurses and physicians because without good nursing care, hospitalists simply cannot provide good medical care.”

There is another way hospitalists can help address verbal abuse. “Studies consistently show that nurses are hesitant to report episodes of verbal abuse,” Dr. Rappaport says, “whether it is from a family, a patient, a physician, or a fellow nurse. Fewer than one in five nurses reports these episodes. One thing that hospitalists can do is work with hospital administration to create an environment that is more proactive in addressing these concerns and allowing nurses to feel more support in this area.”

Only 60% of respondents to the ISMP survey felt their organization had clearly defined an effective process for handling disagreements with a medication order’s safety. Only about a third felt the process facilitated their bypassing an intimidating prescriber or their own supervisor if necessary. Although 70% of respondents reported that they thought their organization or manager would support them if they reported intimidating behavior, only 39% of respondents believed their organization was dealing effectively with intimidating behavior.

Untapped Source

Perceptions of intimidation also occur among trainees. When 2,884 students from the class of 2003 at 16 U.S. medical schools completed questionnaires at various times during training, 27% reported having been “harassed” by house staff, 21% by faculty, and 25% by patients.7 Further, 71% reported having been “belittled” by house staff, 63% by faculty, and 43% by patients.

Mistreated students were significantly more likely to have suffered stress, be depressed or suicidal, and less likely to report being glad they trained as a physician.

—David I. Rappaport, MD, pediatric hospitalist, Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del.

This may have an underlying effect on the potential to monitor for patient safety.8,9 Because errors and near misses often result from miscommunication, medical students may be adept at preventing certain types of errors. Students’ observation skills may be just as keen, if not more so, than their more clinically proficient healthcare teammates.8 In four cases from two U.S. academic health centers reported by medical students Samuel Seiden, Cynthia Galvan, and Ruth Lamm in 2006, medical students demonstrated keen attention to detail and appropriately characterized problematic situations with patients—adding another layer of defense within systems safeguarding against patient harm.8 Yet of the 76% of medical students who had observed a medical error, only about half of the students reported the errors to a resident or an attending, despite having received patient-safety training; only 7% reported having used an electronic medical error reporting system.10

By Example

Some intimidation in medical education may be the result of anger toward students and residents over a lack of medical knowledge, says Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans and member of the SHM Board of Directors. “It is natural to feel [that anger]; people abhor in others what they most detest in themselves,’’ he says. “As physicians, a lack of medical knowledge is what we detest in ourselves. But a student’s ignorance is usually a product of where she is in her training; that’s why she is with you.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University, New Orleans

Anger alienates students, absolving them of the guilt of not knowing the information, and demotivating them from learning it. “The lesson to be communicated is that it is OK not to know, but it is not OK to continue to not know,” Dr. Wiese says. “Reprimands should be reserved for the student who does not know, and then after being taught or asked to look it up, continues to not know.”

“The average physician who practices for 30 years will take care of roughly 80,000 people,” estimates Dr. Wiese. “That’s an arithmetic contribution and there is nothing wrong with that. But if you really want to change the world, teaching is the rule. The same 30 years invested in teaching will indirectly affect 400 million people,” he says. “Even better, if you can train your students and residents in the value of coaching their students and residents, well, now you’re talking about 10 billion people that you can affect over the course of a career.”

The question to ask yourself, says Dr. Wiese, is: Do you want to change the world? “If you do, this is the way to do it,” he says.

“For the 30 years in your career, focus on clinical coaching and getting others to clinically coach. That way, especially if you have the right motives in your heart, the right vision for the way you want to see the profession practiced, and the way you want patient care performed, that’s your shot at changing the world.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: practitioners speak up about this unresolved problem (Part I). Available at w.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040311_2.asp. Last accessed June 27, 2007.

- Hagstrom AM. Perceived barriers to implementation of a successful sharps safety program. AORN J. 2006;83(2):391-7.

- Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient Safety Qual Healthc. 2006 Jul-Aug;3:16-24.

- Manderino MA, Berkey N. Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13(1):48-55.

- Pejic AR. Verbal abuse: A problem for pediatric nurses. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(4):271-279.

- Rowe MM, Sherlock H. Stress and verbal abuse in nursing: do burned out nurses eat their young? J Nurs Manag. 2005May;13(3):242-248.

- Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, et al. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):682.

- Seiden SC, Galvan C, Lamm R. Role of medical students in preventing patient harm and enhancing patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Aug;15(4):272-276.

- Wood DF. Bullying and harassment in medical schools. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):664-665.

- Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med. 2006 Jan;81(1):94-101.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: Mapping a plan for cultural change in healthcare (Part II). Available at www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040325.asp Last accessed July 2, 2007.