User login

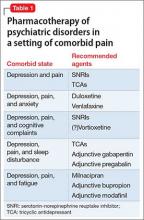

Patients who have chronic pain and those with a major depressive disorder (MDD) share clinical features, including fatigue, cognitive complaints, and functional limitation. Sleep disturbance and anxiety are common with both disorders. Because pain and depression share common neurobiological pathways (see Part 1 of this article in the February 2016 issue and at CurrentPsychiatry.com) and clinical manifestations, you can use similar strategies and, often, the same agents to treat both conditions when they occur together (Table 1).

What are the medical options?

Antidepressants. Using an antidepressant to treat chronic pain is a common practice in primary care and specialty practice. Antidepressants that modulate multiple neurotransmitters appear to be more efficacious than those with a single mechanism of action.1 Convergent evidence from preclinical and clinical studies supports the use of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) as more effective analgesic agents, compared with the mostly noradrenergic antidepressants, which, in turn, are more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).2 The mechanism of the analgesic action of antidepressants appears to rely on their inhibitory effects of norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake, thereby elevating the performance of endogenous descending pain regulatory pathways.3

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), primarily amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and desipramine, have the advantage of years of clinical experience and low cost. Their side effect burden, however, is higher, especially in geriatric patients. Dose-dependent side effects include sedation, constipation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and orthostatic hypotension.

TCAs must be used with caution in patients with suicidal ideation because of the risk of a potentially lethal intentional overdose.

The key to using a TCA is to start with a low dosage, followed by slow titration. Typically, the dosages of TCAs used in clinical trials that focused on pain have been lower (25 to 100 mg/d of amitriptyline or equivalent) than the dosage typically necessary for treating depression; however, some experts have found that titrating TCAs to higher dosages with an option of monitoring serum levels may benefit some patients.4

SNRIs are considered first-line agents for both neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. Duloxetine has been shown to be effective in both conditions5; venlafaxine also has shown efficacy in neuropathic pain.6 Milnacipran, another SNRI that blocks 5-HT, and norepinephrine equally and exerts a mild N-methyl-D-aspartate inhibition, has proven efficacy in fibromyalgia.7,8

SSRIs for alleviating central pain or neuropathic pain are supported by minimal evidence only.9 A review of the effectiveness of various antidepressants on pain in diabetic neuropathy concluded that fluoxetine was no more effective than placebo.10,11 Schreiber and Pick11 evaluated the antinociceptive properties of several SSRIs and offered the opinion that fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and citalopram were, at best, weak antinociceptors.

Opioids. Data on the long-term benefits of opioids are limited, except for use in carefully selected patients; in any case, risk of abuse, diversion, and even death with these agents is quite high.12 Also, there is evidence that opioid-induced hyperalgesia might limit the usefulness of opioids for controlling chronic pain.13

Gabapentin and pregabalin, both anticonvulsants, act by binding to the α-2-σ subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels within the CNS.14 By reducing calcium influx at nerve terminals, the drugs diminish the release of several neurotransmitters, including glutamate, noradrenaline, and substance P. This mechanism is thought to be the basis for the analgesic, anticonvulsant, and anxiolytic effects of these drugs.15

Gabapentin and pregabalin have been shown to decrease pain intensity and improve quality of life and function in patients with neuropathic pain conditions. Pregabalin also has shown efficacy in treating central neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.16

Added benefits of these drugs is that they have (1) a better side effect profile than TCAs and (2) fewer drug interactions when they are used as a component of combination therapy. Pregabalin has the additional advantage of less-frequent dosing, linear pharmacokinetics, and a predictable dose-response relationship.17

Addressing other comorbid psychiatric conditions

Sleep disturbance is common among patients with chronic pain. Sleep deprivation causes a hyperexcitable state that amplifies the pain response.18

When a patient presents with chronic pain, depression, and disturbed sleep, consider using a sedating antidepressant, such as a TCA. Alternatively, gabapentin or pregabalin can be added to an SNRI; anticonvulsants have been shown to improve quality of sleep.19 Cognitive-behavioral interventions targeting sleep disturbance may be a helpful adjunct in these patients.20

When anxiety is comorbid with chronic pain, antidepressants with proven efficacy in treating anxiety disorders, such as duloxetine or venlafaxine, can be used. When chronic pain coexists with a specific anxiety disorder (social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder), an SSRI might be more advantageous than an SNRI,21 especially if it is combined with a more efficacious analgesic.

Benzodiazepines should be avoided as a routine treatment for comorbid anxiety and pain, because these agents can produce sedation and cognitive interference, and carry the potential for dependence.

Fatigue. In patients who, in addition to pain and depression, complain of fatigue, an activating agent such as milnacipran or adjunct bupropion might be preferable to other agents. Modafinil has been shown to be a well-tolerated and potentially effective augmenting agent for antidepressants when fatigue and sleepiness are present as residual symptoms22; consider them as adjuncts when managing patients who have chronic pain and depression that manifests as excessive sleepiness and/or fatigue.

Cognitive complaints. We have noted that disturbances of cognition are common in patients with depression and chronic pain, and that cognitive dysfunction might improve after antidepressant treatment.

Studies suggest that SSRIs, duloxetine, and other antidepressants, such as bupropion, might exert a positive effect on learning, memory, and executive function in depressed patients.23 Beneficial effects of antidepressants may be “pseudo-specific,” however—that is, predominantly a reflection of overall improvement in mood, not on specific amelioration of the cognitive disturbance.

Vortioxetine has shown promise in improving cognitive function in adults with MDD; its cognitive benefits are largely independent of its antidepressant effect.24 The utility of vortioxetine in chronic pain patients has not been studied, but its positive impact on mood, anxiety, sleep, and cognition might make it a consideration for patients with comorbid depression—although it is uncertain at this time whether putative noradrenergic activity makes it suitable for use in chronic pain disorders.

Last, avoid TCAs in patients who have cognitive complaints. These agents have anticholinergic effects that can have an adverse impact on cognitive function.

Cautions: Drug−drug interactions, suicide risk, disrupted sleep

Avoiding drug−drug interactions is an important consideration when treating comorbid disorders. Many chronic pain patients take over-the-counter or prescribed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for analgesia; these agents can increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when they are combined with an SSRI or an SNRI.

The use of the opioid tramadol with an SNRI or a TCA is discouraged because of the risk of serotonin syndrome.

Combining a sedating antidepressant, such as a TCA, with gabapentin or pregabalin can increase the risk of CNS depression and psychomotor impairment, especially in geriatric patients. An opioid analgesic is likely to amplify these effects.

Suicidal ideation is not uncommon in patients with chronic pain and depression. To minimize the risk of suicide in patients with a chronic pain disorder, you should ensure optimal pain control by combining the most efficacious analgesic agent with psychotherapeutic interventions and optimal antidepressant treatment. Furthermore, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (see the discussion below) might not only improve pain coping skills, but also ameliorate catastrophizing, anxiety, and concomitant sleep disturbance.

Complaints of sleep disturbance and anxiety can compound the risk of suicide in a chronic pain patient. When possible, these complex patients should be treated by a multidisciplinary team that includes a pain management specialist, psychotherapist, and primary care clinician. It is important to strengthen the clinician−patient relationship to facilitate close monitoring of symptoms and to provide a trusting environment in which patients feel free to discuss thoughts of suicide or self-harm. For such patients, prescribing opiates and TCAs in small quantities is a prudent action.

When a patient struggles with suicidal thoughts, his (her) family might need to dispense these medications. Most important, if a patient is actively suicidal, consider referral to an inpatient facility or intensive outpatient program, where aggressive treatment of depressive symptoms and intensive monitoring and support can be provided.25

Usefulness of non-drug interventions

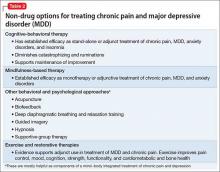

There is, of course, a diversity of non-drug treatments for MDD and for chronic pain; discussion here focuses primarily on modalities with established efficacy in both disease states (Table 2). On rare occasions, non-drug treatments can constitute a stand-alone approach; most often, they are incorporated into a multimodal treatment plan or applied as an adjunct intervention.26

Psychotherapy. The most robust evidence supports the use of CBT in addressing MDD and chronic pain—occurring individually and comorbidly.26-28 Efficacy is well established in MDD, as monotherapy and adjunct treatment, spanning acute and maintenance phases.

Furthermore, CBT also has support from randomized trials, meta-analyses, and treatment guidelines, either as monotherapy or co-therapy for both short-term relief and long-term pain reduction. Additionally, CBT has demonstrated value for relieving pain-related disability.26,28

Combination of a special form of CBT, rumination-focused CBT with ongoing pharmacological therapy over a 26-week period in a group of medication-refractory MDD patients produced a remission rate of 62%, compared with 21% in a treatment-as-usual group.29 This is of particular interest in chronic pain patients, because rumination-related phenomena of pain catastrophizing and avoidance facilitate a transition from acute to chronic pain, while augmenting pain severity and associated disability.30

Catastrophizing also has been implicated in mediating the relationship between pain and sleep disturbance. Not surprisingly, a randomized controlled study demonstrated the benefit of 8-week, Internet-delivered CBT in patients suffering from comorbid chronic pain, depression, and anxiety. Treatment significantly diminished pain catastrophizing, depression, and anxiety; maintenance of improvement was demonstrated after 1 year of follow-up.31

Other behavioral and psychological approaches. Biofeedback, mindfulness-based stress reduction, relaxation training and diaphragmatic breathing, guided imagery, hypnosis, and supportive groups might play an important role as components of an integrated mind−body approach to chronic pain,28,32,33 while also providing mood benefits.

Exercise. The role of exercise as a primary treatment of MDD continues to be controversial, but its benefits as an add-on intervention are indisputable. Exercise not only complements pharmacotherapy to produce greater reduction in depressive scores and improvement in quality of life, it might aid in reestablishing social contacts when conducted in a group setting—an effect that can be of great value in both MDD and chronic pain.34

Exercise and restorative therapies provide several benefits for chronic pain patients, including:

- improved pain control, cognition, and mood

- greater strength and endurance

- cardiovascular and metabolic benefits

- improved bone health and functionality.26,28,32,33,35

To achieve optimal benefit, an exercise program must be customized to fit the patient’s physical condition, level of fitness, and specific type of pain.35 Preliminary evidence suggests that, beyond improvement in pain and functionality, exercise might reduce depressive symptoms in chronic pain patients.36

1. Sharp J, Keefe B. Psychiatry in chronic pain: a review and update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7(3):213-219.

2. Fishbain DA. Polypharmacy treatment approaches to the psychiatric and somatic comorbidities found in patients with chronic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(suppl 3):S56-S63.

3. Schug SA, Goddard C. Recent advances in the pharmacological management of acute and chronic pain. Ann Palliat Med. 2014;3(4):263-275.

4. Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Bair MJ. Pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: a synthesis of recommendations from systematic reviews. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(3):206-219.

5. Lunn MP, Hughes RA, Wiffen PJ. Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD007115. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007115.pub3.

6. Rowbotham MC, Goli V, Kunz NR, et al. Venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain. 2004;110(3):697-706.

7. Kranzler JD, Gendreau JF, Rao SG. The psychopharmacology of fibromyalgia: a drug development perspective. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;36(1):165-213.

8. Pae CU, Marks DM, Shah M, et al. Milnacipran: beyond a role of antidepressant. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(6):355-363.

9. Depression and pain. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1970-1978.

10. Max MB, Lynch SA, Muir J, et al. Effects of desipramine, amitriptyline, and fluoxetine on pain in diabetic neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(19):1250-1256.

11. Schreiber S, Pick CG. From selective to highly selective SSRIs: a comparison of the antinociceptive properties of fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram and escitalopram. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16(6):464-468.

12. Freynhagen R, Geisslinger G, Schug SA. Opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. BMJ. 2013;346:f2937. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2937.

13. Silverman SM. Opioid induced hyperalgesia: clinical implications for the pain practitioner. Pain Physician. 2009;12(3):679-684.

14. Bauer CS, Nieto-Rostro M, Rahman W, et al. The increased trafficking of the calcium channel subunit α2σ-1 to presynaptic terminals in neuropathic pain is inhibited by the α2σ ligand pregabalin. J Neurosci. 2009;29(13):4076-4088.

15. Dooley DJ, Taylor CP, Donevan S, et al. Ca2+ channel α2σ ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmission [Erratum in: Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28(4):151]. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28(2):75-82.

16. Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia - an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD010567. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010567.pub2.

17. Finnerup NB, Otto M, Jensen TS, et al. An evidence-based algorithm for the treatment of neuropathic pain. MedGenMed. 2007;9(2):36.

18. Nicholson B, Verma S. Comorbidities in chronic neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2004;5(suppl 1):S9-S27.

19. Sammaritano M, Sherwin A. Effect of anticonvulsants on sleep. Neurology. 2000;54(5 suppl 1):S16-S24.

20. Morin CM, Vallières A, Guay B, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2005-2015.

21. Fishbain DA. Polypharmacy treatment approaches to the psychiatric and somatic comorbidities found in patients with chronic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(suppl 3):S56-S63.

22. Fava M, Thase ME, DeBattista C. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study of modafinil augmentation in partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with persistent fatigue and sleepiness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):85-93.

23. Baune BT, Renger L. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive dysfunction and functional ability in clinical depression—a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(1):25-50.

24. McIntyre RS, Lophaven S, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vortioxetine on cognitive function in depressed adults. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(10):1557-1567.

25. Cheatle MD. Depression, chronic pain, and suicide by overdose: on the edge. Pain Med. 2011;12(suppl 2):S43-S48.

26. Chang KL, Fillingim R, Hurley RW, et al. Chronic pain management: nonpharmacological therapies for chronic pain. FP Essent. 2015;432:21-26.

27. Cuijpers P, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioural therapy and other psychological treatments for adult depression: meta-analytic study of publication bias. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(3):173-178.

28. Lambert M. ICSI releases guideline on chronic pain assessment and management. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(4):434-439.

29. Watkins ER, Mullan E, Wingrove J, et al. Rumination-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy for residual depression: phase II randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):317-322.

30. Turk DC, Wilson HD. Fear of pain as a prognostic factor in chronic pain: conceptual models, assessment, and treatment implications. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14(2):88-95.

31. Buhrman M, Syk M, Burvall O, et al. Individualized guided Internet-delivered cognitive-behavior therapy for chronic pain patients with comorbid depression and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(6):504-516.

32. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management; American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Practice guidelines for chronic pain management: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(4):810-833.

33. Theadom A, Cropley M, Smith HE, et al. Mind and body therapy for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD001980. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001980.pub3.

34. Mura G, Moro MF, Patten SB, et al. Exercise as an add-on strategy for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(6):496-508.

35. Kroll HR. Exercise therapy for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):263-281.

36. Liang H, Zhang H, Ji H, et al. Effects of home-based exercise intervention on health-related quality of life for patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(10):1737-1744.

Patients who have chronic pain and those with a major depressive disorder (MDD) share clinical features, including fatigue, cognitive complaints, and functional limitation. Sleep disturbance and anxiety are common with both disorders. Because pain and depression share common neurobiological pathways (see Part 1 of this article in the February 2016 issue and at CurrentPsychiatry.com) and clinical manifestations, you can use similar strategies and, often, the same agents to treat both conditions when they occur together (Table 1).

What are the medical options?

Antidepressants. Using an antidepressant to treat chronic pain is a common practice in primary care and specialty practice. Antidepressants that modulate multiple neurotransmitters appear to be more efficacious than those with a single mechanism of action.1 Convergent evidence from preclinical and clinical studies supports the use of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) as more effective analgesic agents, compared with the mostly noradrenergic antidepressants, which, in turn, are more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).2 The mechanism of the analgesic action of antidepressants appears to rely on their inhibitory effects of norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake, thereby elevating the performance of endogenous descending pain regulatory pathways.3

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), primarily amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and desipramine, have the advantage of years of clinical experience and low cost. Their side effect burden, however, is higher, especially in geriatric patients. Dose-dependent side effects include sedation, constipation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and orthostatic hypotension.

TCAs must be used with caution in patients with suicidal ideation because of the risk of a potentially lethal intentional overdose.

The key to using a TCA is to start with a low dosage, followed by slow titration. Typically, the dosages of TCAs used in clinical trials that focused on pain have been lower (25 to 100 mg/d of amitriptyline or equivalent) than the dosage typically necessary for treating depression; however, some experts have found that titrating TCAs to higher dosages with an option of monitoring serum levels may benefit some patients.4

SNRIs are considered first-line agents for both neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. Duloxetine has been shown to be effective in both conditions5; venlafaxine also has shown efficacy in neuropathic pain.6 Milnacipran, another SNRI that blocks 5-HT, and norepinephrine equally and exerts a mild N-methyl-D-aspartate inhibition, has proven efficacy in fibromyalgia.7,8

SSRIs for alleviating central pain or neuropathic pain are supported by minimal evidence only.9 A review of the effectiveness of various antidepressants on pain in diabetic neuropathy concluded that fluoxetine was no more effective than placebo.10,11 Schreiber and Pick11 evaluated the antinociceptive properties of several SSRIs and offered the opinion that fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and citalopram were, at best, weak antinociceptors.

Opioids. Data on the long-term benefits of opioids are limited, except for use in carefully selected patients; in any case, risk of abuse, diversion, and even death with these agents is quite high.12 Also, there is evidence that opioid-induced hyperalgesia might limit the usefulness of opioids for controlling chronic pain.13

Gabapentin and pregabalin, both anticonvulsants, act by binding to the α-2-σ subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels within the CNS.14 By reducing calcium influx at nerve terminals, the drugs diminish the release of several neurotransmitters, including glutamate, noradrenaline, and substance P. This mechanism is thought to be the basis for the analgesic, anticonvulsant, and anxiolytic effects of these drugs.15

Gabapentin and pregabalin have been shown to decrease pain intensity and improve quality of life and function in patients with neuropathic pain conditions. Pregabalin also has shown efficacy in treating central neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.16

Added benefits of these drugs is that they have (1) a better side effect profile than TCAs and (2) fewer drug interactions when they are used as a component of combination therapy. Pregabalin has the additional advantage of less-frequent dosing, linear pharmacokinetics, and a predictable dose-response relationship.17

Addressing other comorbid psychiatric conditions

Sleep disturbance is common among patients with chronic pain. Sleep deprivation causes a hyperexcitable state that amplifies the pain response.18

When a patient presents with chronic pain, depression, and disturbed sleep, consider using a sedating antidepressant, such as a TCA. Alternatively, gabapentin or pregabalin can be added to an SNRI; anticonvulsants have been shown to improve quality of sleep.19 Cognitive-behavioral interventions targeting sleep disturbance may be a helpful adjunct in these patients.20

When anxiety is comorbid with chronic pain, antidepressants with proven efficacy in treating anxiety disorders, such as duloxetine or venlafaxine, can be used. When chronic pain coexists with a specific anxiety disorder (social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder), an SSRI might be more advantageous than an SNRI,21 especially if it is combined with a more efficacious analgesic.

Benzodiazepines should be avoided as a routine treatment for comorbid anxiety and pain, because these agents can produce sedation and cognitive interference, and carry the potential for dependence.

Fatigue. In patients who, in addition to pain and depression, complain of fatigue, an activating agent such as milnacipran or adjunct bupropion might be preferable to other agents. Modafinil has been shown to be a well-tolerated and potentially effective augmenting agent for antidepressants when fatigue and sleepiness are present as residual symptoms22; consider them as adjuncts when managing patients who have chronic pain and depression that manifests as excessive sleepiness and/or fatigue.

Cognitive complaints. We have noted that disturbances of cognition are common in patients with depression and chronic pain, and that cognitive dysfunction might improve after antidepressant treatment.

Studies suggest that SSRIs, duloxetine, and other antidepressants, such as bupropion, might exert a positive effect on learning, memory, and executive function in depressed patients.23 Beneficial effects of antidepressants may be “pseudo-specific,” however—that is, predominantly a reflection of overall improvement in mood, not on specific amelioration of the cognitive disturbance.

Vortioxetine has shown promise in improving cognitive function in adults with MDD; its cognitive benefits are largely independent of its antidepressant effect.24 The utility of vortioxetine in chronic pain patients has not been studied, but its positive impact on mood, anxiety, sleep, and cognition might make it a consideration for patients with comorbid depression—although it is uncertain at this time whether putative noradrenergic activity makes it suitable for use in chronic pain disorders.

Last, avoid TCAs in patients who have cognitive complaints. These agents have anticholinergic effects that can have an adverse impact on cognitive function.

Cautions: Drug−drug interactions, suicide risk, disrupted sleep

Avoiding drug−drug interactions is an important consideration when treating comorbid disorders. Many chronic pain patients take over-the-counter or prescribed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for analgesia; these agents can increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when they are combined with an SSRI or an SNRI.

The use of the opioid tramadol with an SNRI or a TCA is discouraged because of the risk of serotonin syndrome.

Combining a sedating antidepressant, such as a TCA, with gabapentin or pregabalin can increase the risk of CNS depression and psychomotor impairment, especially in geriatric patients. An opioid analgesic is likely to amplify these effects.

Suicidal ideation is not uncommon in patients with chronic pain and depression. To minimize the risk of suicide in patients with a chronic pain disorder, you should ensure optimal pain control by combining the most efficacious analgesic agent with psychotherapeutic interventions and optimal antidepressant treatment. Furthermore, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (see the discussion below) might not only improve pain coping skills, but also ameliorate catastrophizing, anxiety, and concomitant sleep disturbance.

Complaints of sleep disturbance and anxiety can compound the risk of suicide in a chronic pain patient. When possible, these complex patients should be treated by a multidisciplinary team that includes a pain management specialist, psychotherapist, and primary care clinician. It is important to strengthen the clinician−patient relationship to facilitate close monitoring of symptoms and to provide a trusting environment in which patients feel free to discuss thoughts of suicide or self-harm. For such patients, prescribing opiates and TCAs in small quantities is a prudent action.

When a patient struggles with suicidal thoughts, his (her) family might need to dispense these medications. Most important, if a patient is actively suicidal, consider referral to an inpatient facility or intensive outpatient program, where aggressive treatment of depressive symptoms and intensive monitoring and support can be provided.25

Usefulness of non-drug interventions

There is, of course, a diversity of non-drug treatments for MDD and for chronic pain; discussion here focuses primarily on modalities with established efficacy in both disease states (Table 2). On rare occasions, non-drug treatments can constitute a stand-alone approach; most often, they are incorporated into a multimodal treatment plan or applied as an adjunct intervention.26

Psychotherapy. The most robust evidence supports the use of CBT in addressing MDD and chronic pain—occurring individually and comorbidly.26-28 Efficacy is well established in MDD, as monotherapy and adjunct treatment, spanning acute and maintenance phases.

Furthermore, CBT also has support from randomized trials, meta-analyses, and treatment guidelines, either as monotherapy or co-therapy for both short-term relief and long-term pain reduction. Additionally, CBT has demonstrated value for relieving pain-related disability.26,28

Combination of a special form of CBT, rumination-focused CBT with ongoing pharmacological therapy over a 26-week period in a group of medication-refractory MDD patients produced a remission rate of 62%, compared with 21% in a treatment-as-usual group.29 This is of particular interest in chronic pain patients, because rumination-related phenomena of pain catastrophizing and avoidance facilitate a transition from acute to chronic pain, while augmenting pain severity and associated disability.30

Catastrophizing also has been implicated in mediating the relationship between pain and sleep disturbance. Not surprisingly, a randomized controlled study demonstrated the benefit of 8-week, Internet-delivered CBT in patients suffering from comorbid chronic pain, depression, and anxiety. Treatment significantly diminished pain catastrophizing, depression, and anxiety; maintenance of improvement was demonstrated after 1 year of follow-up.31

Other behavioral and psychological approaches. Biofeedback, mindfulness-based stress reduction, relaxation training and diaphragmatic breathing, guided imagery, hypnosis, and supportive groups might play an important role as components of an integrated mind−body approach to chronic pain,28,32,33 while also providing mood benefits.

Exercise. The role of exercise as a primary treatment of MDD continues to be controversial, but its benefits as an add-on intervention are indisputable. Exercise not only complements pharmacotherapy to produce greater reduction in depressive scores and improvement in quality of life, it might aid in reestablishing social contacts when conducted in a group setting—an effect that can be of great value in both MDD and chronic pain.34

Exercise and restorative therapies provide several benefits for chronic pain patients, including:

- improved pain control, cognition, and mood

- greater strength and endurance

- cardiovascular and metabolic benefits

- improved bone health and functionality.26,28,32,33,35

To achieve optimal benefit, an exercise program must be customized to fit the patient’s physical condition, level of fitness, and specific type of pain.35 Preliminary evidence suggests that, beyond improvement in pain and functionality, exercise might reduce depressive symptoms in chronic pain patients.36

Patients who have chronic pain and those with a major depressive disorder (MDD) share clinical features, including fatigue, cognitive complaints, and functional limitation. Sleep disturbance and anxiety are common with both disorders. Because pain and depression share common neurobiological pathways (see Part 1 of this article in the February 2016 issue and at CurrentPsychiatry.com) and clinical manifestations, you can use similar strategies and, often, the same agents to treat both conditions when they occur together (Table 1).

What are the medical options?

Antidepressants. Using an antidepressant to treat chronic pain is a common practice in primary care and specialty practice. Antidepressants that modulate multiple neurotransmitters appear to be more efficacious than those with a single mechanism of action.1 Convergent evidence from preclinical and clinical studies supports the use of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) as more effective analgesic agents, compared with the mostly noradrenergic antidepressants, which, in turn, are more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).2 The mechanism of the analgesic action of antidepressants appears to rely on their inhibitory effects of norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake, thereby elevating the performance of endogenous descending pain regulatory pathways.3

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), primarily amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and desipramine, have the advantage of years of clinical experience and low cost. Their side effect burden, however, is higher, especially in geriatric patients. Dose-dependent side effects include sedation, constipation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and orthostatic hypotension.

TCAs must be used with caution in patients with suicidal ideation because of the risk of a potentially lethal intentional overdose.

The key to using a TCA is to start with a low dosage, followed by slow titration. Typically, the dosages of TCAs used in clinical trials that focused on pain have been lower (25 to 100 mg/d of amitriptyline or equivalent) than the dosage typically necessary for treating depression; however, some experts have found that titrating TCAs to higher dosages with an option of monitoring serum levels may benefit some patients.4

SNRIs are considered first-line agents for both neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. Duloxetine has been shown to be effective in both conditions5; venlafaxine also has shown efficacy in neuropathic pain.6 Milnacipran, another SNRI that blocks 5-HT, and norepinephrine equally and exerts a mild N-methyl-D-aspartate inhibition, has proven efficacy in fibromyalgia.7,8

SSRIs for alleviating central pain or neuropathic pain are supported by minimal evidence only.9 A review of the effectiveness of various antidepressants on pain in diabetic neuropathy concluded that fluoxetine was no more effective than placebo.10,11 Schreiber and Pick11 evaluated the antinociceptive properties of several SSRIs and offered the opinion that fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and citalopram were, at best, weak antinociceptors.

Opioids. Data on the long-term benefits of opioids are limited, except for use in carefully selected patients; in any case, risk of abuse, diversion, and even death with these agents is quite high.12 Also, there is evidence that opioid-induced hyperalgesia might limit the usefulness of opioids for controlling chronic pain.13

Gabapentin and pregabalin, both anticonvulsants, act by binding to the α-2-σ subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels within the CNS.14 By reducing calcium influx at nerve terminals, the drugs diminish the release of several neurotransmitters, including glutamate, noradrenaline, and substance P. This mechanism is thought to be the basis for the analgesic, anticonvulsant, and anxiolytic effects of these drugs.15

Gabapentin and pregabalin have been shown to decrease pain intensity and improve quality of life and function in patients with neuropathic pain conditions. Pregabalin also has shown efficacy in treating central neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.16

Added benefits of these drugs is that they have (1) a better side effect profile than TCAs and (2) fewer drug interactions when they are used as a component of combination therapy. Pregabalin has the additional advantage of less-frequent dosing, linear pharmacokinetics, and a predictable dose-response relationship.17

Addressing other comorbid psychiatric conditions

Sleep disturbance is common among patients with chronic pain. Sleep deprivation causes a hyperexcitable state that amplifies the pain response.18

When a patient presents with chronic pain, depression, and disturbed sleep, consider using a sedating antidepressant, such as a TCA. Alternatively, gabapentin or pregabalin can be added to an SNRI; anticonvulsants have been shown to improve quality of sleep.19 Cognitive-behavioral interventions targeting sleep disturbance may be a helpful adjunct in these patients.20

When anxiety is comorbid with chronic pain, antidepressants with proven efficacy in treating anxiety disorders, such as duloxetine or venlafaxine, can be used. When chronic pain coexists with a specific anxiety disorder (social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder), an SSRI might be more advantageous than an SNRI,21 especially if it is combined with a more efficacious analgesic.

Benzodiazepines should be avoided as a routine treatment for comorbid anxiety and pain, because these agents can produce sedation and cognitive interference, and carry the potential for dependence.

Fatigue. In patients who, in addition to pain and depression, complain of fatigue, an activating agent such as milnacipran or adjunct bupropion might be preferable to other agents. Modafinil has been shown to be a well-tolerated and potentially effective augmenting agent for antidepressants when fatigue and sleepiness are present as residual symptoms22; consider them as adjuncts when managing patients who have chronic pain and depression that manifests as excessive sleepiness and/or fatigue.

Cognitive complaints. We have noted that disturbances of cognition are common in patients with depression and chronic pain, and that cognitive dysfunction might improve after antidepressant treatment.

Studies suggest that SSRIs, duloxetine, and other antidepressants, such as bupropion, might exert a positive effect on learning, memory, and executive function in depressed patients.23 Beneficial effects of antidepressants may be “pseudo-specific,” however—that is, predominantly a reflection of overall improvement in mood, not on specific amelioration of the cognitive disturbance.

Vortioxetine has shown promise in improving cognitive function in adults with MDD; its cognitive benefits are largely independent of its antidepressant effect.24 The utility of vortioxetine in chronic pain patients has not been studied, but its positive impact on mood, anxiety, sleep, and cognition might make it a consideration for patients with comorbid depression—although it is uncertain at this time whether putative noradrenergic activity makes it suitable for use in chronic pain disorders.

Last, avoid TCAs in patients who have cognitive complaints. These agents have anticholinergic effects that can have an adverse impact on cognitive function.

Cautions: Drug−drug interactions, suicide risk, disrupted sleep

Avoiding drug−drug interactions is an important consideration when treating comorbid disorders. Many chronic pain patients take over-the-counter or prescribed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for analgesia; these agents can increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when they are combined with an SSRI or an SNRI.

The use of the opioid tramadol with an SNRI or a TCA is discouraged because of the risk of serotonin syndrome.

Combining a sedating antidepressant, such as a TCA, with gabapentin or pregabalin can increase the risk of CNS depression and psychomotor impairment, especially in geriatric patients. An opioid analgesic is likely to amplify these effects.

Suicidal ideation is not uncommon in patients with chronic pain and depression. To minimize the risk of suicide in patients with a chronic pain disorder, you should ensure optimal pain control by combining the most efficacious analgesic agent with psychotherapeutic interventions and optimal antidepressant treatment. Furthermore, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (see the discussion below) might not only improve pain coping skills, but also ameliorate catastrophizing, anxiety, and concomitant sleep disturbance.

Complaints of sleep disturbance and anxiety can compound the risk of suicide in a chronic pain patient. When possible, these complex patients should be treated by a multidisciplinary team that includes a pain management specialist, psychotherapist, and primary care clinician. It is important to strengthen the clinician−patient relationship to facilitate close monitoring of symptoms and to provide a trusting environment in which patients feel free to discuss thoughts of suicide or self-harm. For such patients, prescribing opiates and TCAs in small quantities is a prudent action.

When a patient struggles with suicidal thoughts, his (her) family might need to dispense these medications. Most important, if a patient is actively suicidal, consider referral to an inpatient facility or intensive outpatient program, where aggressive treatment of depressive symptoms and intensive monitoring and support can be provided.25

Usefulness of non-drug interventions

There is, of course, a diversity of non-drug treatments for MDD and for chronic pain; discussion here focuses primarily on modalities with established efficacy in both disease states (Table 2). On rare occasions, non-drug treatments can constitute a stand-alone approach; most often, they are incorporated into a multimodal treatment plan or applied as an adjunct intervention.26

Psychotherapy. The most robust evidence supports the use of CBT in addressing MDD and chronic pain—occurring individually and comorbidly.26-28 Efficacy is well established in MDD, as monotherapy and adjunct treatment, spanning acute and maintenance phases.

Furthermore, CBT also has support from randomized trials, meta-analyses, and treatment guidelines, either as monotherapy or co-therapy for both short-term relief and long-term pain reduction. Additionally, CBT has demonstrated value for relieving pain-related disability.26,28

Combination of a special form of CBT, rumination-focused CBT with ongoing pharmacological therapy over a 26-week period in a group of medication-refractory MDD patients produced a remission rate of 62%, compared with 21% in a treatment-as-usual group.29 This is of particular interest in chronic pain patients, because rumination-related phenomena of pain catastrophizing and avoidance facilitate a transition from acute to chronic pain, while augmenting pain severity and associated disability.30

Catastrophizing also has been implicated in mediating the relationship between pain and sleep disturbance. Not surprisingly, a randomized controlled study demonstrated the benefit of 8-week, Internet-delivered CBT in patients suffering from comorbid chronic pain, depression, and anxiety. Treatment significantly diminished pain catastrophizing, depression, and anxiety; maintenance of improvement was demonstrated after 1 year of follow-up.31

Other behavioral and psychological approaches. Biofeedback, mindfulness-based stress reduction, relaxation training and diaphragmatic breathing, guided imagery, hypnosis, and supportive groups might play an important role as components of an integrated mind−body approach to chronic pain,28,32,33 while also providing mood benefits.

Exercise. The role of exercise as a primary treatment of MDD continues to be controversial, but its benefits as an add-on intervention are indisputable. Exercise not only complements pharmacotherapy to produce greater reduction in depressive scores and improvement in quality of life, it might aid in reestablishing social contacts when conducted in a group setting—an effect that can be of great value in both MDD and chronic pain.34

Exercise and restorative therapies provide several benefits for chronic pain patients, including:

- improved pain control, cognition, and mood

- greater strength and endurance

- cardiovascular and metabolic benefits

- improved bone health and functionality.26,28,32,33,35

To achieve optimal benefit, an exercise program must be customized to fit the patient’s physical condition, level of fitness, and specific type of pain.35 Preliminary evidence suggests that, beyond improvement in pain and functionality, exercise might reduce depressive symptoms in chronic pain patients.36

1. Sharp J, Keefe B. Psychiatry in chronic pain: a review and update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7(3):213-219.

2. Fishbain DA. Polypharmacy treatment approaches to the psychiatric and somatic comorbidities found in patients with chronic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(suppl 3):S56-S63.

3. Schug SA, Goddard C. Recent advances in the pharmacological management of acute and chronic pain. Ann Palliat Med. 2014;3(4):263-275.

4. Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Bair MJ. Pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: a synthesis of recommendations from systematic reviews. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(3):206-219.

5. Lunn MP, Hughes RA, Wiffen PJ. Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD007115. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007115.pub3.

6. Rowbotham MC, Goli V, Kunz NR, et al. Venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain. 2004;110(3):697-706.

7. Kranzler JD, Gendreau JF, Rao SG. The psychopharmacology of fibromyalgia: a drug development perspective. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;36(1):165-213.

8. Pae CU, Marks DM, Shah M, et al. Milnacipran: beyond a role of antidepressant. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(6):355-363.

9. Depression and pain. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1970-1978.

10. Max MB, Lynch SA, Muir J, et al. Effects of desipramine, amitriptyline, and fluoxetine on pain in diabetic neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(19):1250-1256.

11. Schreiber S, Pick CG. From selective to highly selective SSRIs: a comparison of the antinociceptive properties of fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram and escitalopram. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16(6):464-468.

12. Freynhagen R, Geisslinger G, Schug SA. Opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. BMJ. 2013;346:f2937. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2937.

13. Silverman SM. Opioid induced hyperalgesia: clinical implications for the pain practitioner. Pain Physician. 2009;12(3):679-684.

14. Bauer CS, Nieto-Rostro M, Rahman W, et al. The increased trafficking of the calcium channel subunit α2σ-1 to presynaptic terminals in neuropathic pain is inhibited by the α2σ ligand pregabalin. J Neurosci. 2009;29(13):4076-4088.

15. Dooley DJ, Taylor CP, Donevan S, et al. Ca2+ channel α2σ ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmission [Erratum in: Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28(4):151]. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28(2):75-82.

16. Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia - an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD010567. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010567.pub2.

17. Finnerup NB, Otto M, Jensen TS, et al. An evidence-based algorithm for the treatment of neuropathic pain. MedGenMed. 2007;9(2):36.

18. Nicholson B, Verma S. Comorbidities in chronic neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2004;5(suppl 1):S9-S27.

19. Sammaritano M, Sherwin A. Effect of anticonvulsants on sleep. Neurology. 2000;54(5 suppl 1):S16-S24.

20. Morin CM, Vallières A, Guay B, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2005-2015.

21. Fishbain DA. Polypharmacy treatment approaches to the psychiatric and somatic comorbidities found in patients with chronic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(suppl 3):S56-S63.

22. Fava M, Thase ME, DeBattista C. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study of modafinil augmentation in partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with persistent fatigue and sleepiness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):85-93.

23. Baune BT, Renger L. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive dysfunction and functional ability in clinical depression—a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(1):25-50.

24. McIntyre RS, Lophaven S, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vortioxetine on cognitive function in depressed adults. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(10):1557-1567.

25. Cheatle MD. Depression, chronic pain, and suicide by overdose: on the edge. Pain Med. 2011;12(suppl 2):S43-S48.

26. Chang KL, Fillingim R, Hurley RW, et al. Chronic pain management: nonpharmacological therapies for chronic pain. FP Essent. 2015;432:21-26.

27. Cuijpers P, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioural therapy and other psychological treatments for adult depression: meta-analytic study of publication bias. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(3):173-178.

28. Lambert M. ICSI releases guideline on chronic pain assessment and management. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(4):434-439.

29. Watkins ER, Mullan E, Wingrove J, et al. Rumination-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy for residual depression: phase II randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):317-322.

30. Turk DC, Wilson HD. Fear of pain as a prognostic factor in chronic pain: conceptual models, assessment, and treatment implications. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14(2):88-95.

31. Buhrman M, Syk M, Burvall O, et al. Individualized guided Internet-delivered cognitive-behavior therapy for chronic pain patients with comorbid depression and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(6):504-516.

32. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management; American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Practice guidelines for chronic pain management: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(4):810-833.

33. Theadom A, Cropley M, Smith HE, et al. Mind and body therapy for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD001980. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001980.pub3.

34. Mura G, Moro MF, Patten SB, et al. Exercise as an add-on strategy for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(6):496-508.

35. Kroll HR. Exercise therapy for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):263-281.

36. Liang H, Zhang H, Ji H, et al. Effects of home-based exercise intervention on health-related quality of life for patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(10):1737-1744.

1. Sharp J, Keefe B. Psychiatry in chronic pain: a review and update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7(3):213-219.

2. Fishbain DA. Polypharmacy treatment approaches to the psychiatric and somatic comorbidities found in patients with chronic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(suppl 3):S56-S63.

3. Schug SA, Goddard C. Recent advances in the pharmacological management of acute and chronic pain. Ann Palliat Med. 2014;3(4):263-275.

4. Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Bair MJ. Pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: a synthesis of recommendations from systematic reviews. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(3):206-219.

5. Lunn MP, Hughes RA, Wiffen PJ. Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD007115. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007115.pub3.

6. Rowbotham MC, Goli V, Kunz NR, et al. Venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain. 2004;110(3):697-706.

7. Kranzler JD, Gendreau JF, Rao SG. The psychopharmacology of fibromyalgia: a drug development perspective. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;36(1):165-213.

8. Pae CU, Marks DM, Shah M, et al. Milnacipran: beyond a role of antidepressant. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(6):355-363.

9. Depression and pain. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1970-1978.

10. Max MB, Lynch SA, Muir J, et al. Effects of desipramine, amitriptyline, and fluoxetine on pain in diabetic neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(19):1250-1256.

11. Schreiber S, Pick CG. From selective to highly selective SSRIs: a comparison of the antinociceptive properties of fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram and escitalopram. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16(6):464-468.

12. Freynhagen R, Geisslinger G, Schug SA. Opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. BMJ. 2013;346:f2937. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2937.

13. Silverman SM. Opioid induced hyperalgesia: clinical implications for the pain practitioner. Pain Physician. 2009;12(3):679-684.

14. Bauer CS, Nieto-Rostro M, Rahman W, et al. The increased trafficking of the calcium channel subunit α2σ-1 to presynaptic terminals in neuropathic pain is inhibited by the α2σ ligand pregabalin. J Neurosci. 2009;29(13):4076-4088.

15. Dooley DJ, Taylor CP, Donevan S, et al. Ca2+ channel α2σ ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmission [Erratum in: Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28(4):151]. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28(2):75-82.

16. Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia - an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD010567. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010567.pub2.

17. Finnerup NB, Otto M, Jensen TS, et al. An evidence-based algorithm for the treatment of neuropathic pain. MedGenMed. 2007;9(2):36.

18. Nicholson B, Verma S. Comorbidities in chronic neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2004;5(suppl 1):S9-S27.

19. Sammaritano M, Sherwin A. Effect of anticonvulsants on sleep. Neurology. 2000;54(5 suppl 1):S16-S24.

20. Morin CM, Vallières A, Guay B, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2005-2015.

21. Fishbain DA. Polypharmacy treatment approaches to the psychiatric and somatic comorbidities found in patients with chronic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(suppl 3):S56-S63.

22. Fava M, Thase ME, DeBattista C. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study of modafinil augmentation in partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with persistent fatigue and sleepiness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):85-93.

23. Baune BT, Renger L. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive dysfunction and functional ability in clinical depression—a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(1):25-50.

24. McIntyre RS, Lophaven S, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vortioxetine on cognitive function in depressed adults. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(10):1557-1567.

25. Cheatle MD. Depression, chronic pain, and suicide by overdose: on the edge. Pain Med. 2011;12(suppl 2):S43-S48.

26. Chang KL, Fillingim R, Hurley RW, et al. Chronic pain management: nonpharmacological therapies for chronic pain. FP Essent. 2015;432:21-26.

27. Cuijpers P, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioural therapy and other psychological treatments for adult depression: meta-analytic study of publication bias. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(3):173-178.

28. Lambert M. ICSI releases guideline on chronic pain assessment and management. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(4):434-439.

29. Watkins ER, Mullan E, Wingrove J, et al. Rumination-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy for residual depression: phase II randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):317-322.

30. Turk DC, Wilson HD. Fear of pain as a prognostic factor in chronic pain: conceptual models, assessment, and treatment implications. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14(2):88-95.

31. Buhrman M, Syk M, Burvall O, et al. Individualized guided Internet-delivered cognitive-behavior therapy for chronic pain patients with comorbid depression and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(6):504-516.

32. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management; American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Practice guidelines for chronic pain management: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(4):810-833.

33. Theadom A, Cropley M, Smith HE, et al. Mind and body therapy for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD001980. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001980.pub3.

34. Mura G, Moro MF, Patten SB, et al. Exercise as an add-on strategy for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(6):496-508.

35. Kroll HR. Exercise therapy for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):263-281.

36. Liang H, Zhang H, Ji H, et al. Effects of home-based exercise intervention on health-related quality of life for patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(10):1737-1744.