User login

Chronic irritation, itching, and pain are only rarely due to infection. These symptoms are more likely to be caused by dermatoses, vaginal abnormalities, and pain syndromes that may be difficult to diagnose. Careful evaluation should include a wet mount and culture to eliminate infection as a cause so that the correct diagnosis can be ascertained and treated.

In Part 2 of this two-part series, we focus on five cases of vulvar dermatologic disruptions:

- atrophic vagina

- irritant and allergic contact dermatitis

- complex vulvar aphthosis

- desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

- inverse psoriasis.

CASE 1. INTROITAL BURNING AND A FEAR OF BREAST CANCER

A 56-year-old woman visits your office for management of recent-onset introital burning during sexual activity. She reports that her commercial lubricant causes irritation. Topical and oral antifungal therapies have not been beneficial. She has a strong family history of breast cancer.

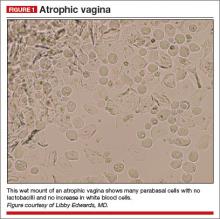

On examination, she exhibits small, smooth labia minora and experiences pain when a cotton swab is pressed against the vestibule. The vagina is also smooth, with scant secretions. Microscopically, these secretions are almost acellular, with no increase in white blood cells and no clue cells, yeast forms, or lactobacilli. The pH is greater than 6.5, and most epithelial cells are parabasal (FIGURE 1).

You prescribe topical estradiol cream for vaginal use three nights per week, but when the patient returns 1 month later, her condition is unchanged. She explains that she never used the cream after reading the package insert, which reports a risk of breast cancer.

Diagnosis: Atrophic vagina (not atrophic vaginitis, as there is no increase in white blood cells).

Treatment: Re-estrogenization should relieve her symptoms.

Several options for local estrogen replacement are available. Creams include estradiol (Estrace) and conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin), the latter of which is arguably slightly more irritating. These are prescribed at a starting dose of 1 g in the vagina three nights per week. After several weeks, they can be titrated to the lowest frequency that controls symptoms.

The risk of vaginal candidiasis is fairly high during the first 2 or 3 weeks of re-estrogenization, so patients should be warned of this possibility. Also consider prophylactic weekly fluconazole or an azole suppository two or three times a week for the first few weeks. Estradiol tablets (Vagifem) inserted in the vagina are effective, less messy, and more expensive, as is the estradiol ring (Estring), which is inserted and changed quarterly.

It is not unusual for a woman to avoid use of topical estrogen out of fear, or to use insufficient amounts only on the vulva, or to use it for only 1 or 2 weeks.1

Women should be scheduled for a return visit to ensure they have been using the estrogen, their wet mount has normalized, and discomfort has cleared.

Related article: Your menopausal patient's breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia. JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD (Cases in Menopause; May 2013)

When a woman is reluctant to use local estrogen

We counsel women that small doses of vaginal estrogen used for limited periods of time are unlikely to influence their breast cancer risk and are the most effective treatment for symptoms of atrophy. Usually, this explanation is sufficient to reassure a woman that topical estrogen is safe. Otherwise, use of commercial personal lubricants (silicone-based lubricants are well tolerated) and moisturizers such as Replens and RePhresh can be comforting.

The topical anesthetics lidocaine 2% jelly or lidocaine 5% ointment (which sometimes burns) can minimize pain with sexual activity for those requiring more than lubrication.

Ospemifene (Osphena) is used by some clinicians in this situation, but this medication is labeled as a risk for all of the same contraindications as systemic estrogen, and it is much more expensive than topical estrogen. Ospemifene is an estrogen agonist/antagonist. Although it is the only oral medication indicated for the treatment of menopause-related dyspareunia, the long-term effects on breast cancer risk are unknown. Also, it has an agonist effect on the endometrium and, again, the long-term risk is unknown.

Related article: New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (News for your Practice; May 2013)

Fluconazole use is contraindicated with ospemifene, as is the use of any estrogen products.

CASE 2. RECALCITRANT ITCHING, BURNING, AND REDNESS

A 25-year-old woman reports anogenital itching, burning, and redness, which have been present for 3 months. She says she developed a yeast infection after antibiotic therapy for a dental infection; the yeast infection was treated with terconazole. She reports an allergic reaction to the terconazole, with immediate severe burning, redness, and swelling. The clobetasol cream she was given to use twice daily also caused burning, so she discontinued it. Her symptoms improved when she tried cool soaks and applied topical benzocaine gel as a local anesthetic. However,

2 weeks later, she experienced increasing redness, itching, and burning. Although the benzocaine relieved these symptoms, it required almost continual reapplication for comfort.

A physical examination of the vulva reveals generalized, poorly demarcated redness, edema, and superficial erosions (FIGURE 2).

Diagnosis: Irritant contact dermatitis (as opposed to allergic contact dermatitis) associated with the use of terconazole and clobetasol. This was followed by allergic contact dermatitis in association with benzocaine.

Treatment: Withdrawal of benzocaine, with reinitiation of cool soaks and a switch to clobetasol ointment rather than cream. Nighttime sedation allows the patient to sleep through the itching and gradually allows her skin to heal.

Contact dermatitis is a fairly common cause of vulvar irritation, with two main types:

- Irritant contact dermatitis—The most common form, it occurs in any individual exposed to an irritating substance in sufficient quantity or frequency. Irritant contact dermatitis is characterized mostly by sensations of rawness or burning and generally is caused by urine, feces, perspiration, friction, alcohols in topical creams, overwashing, and use of harsh soaps.

- Allergic contact dermatitis—This form is characterized by itching, although secondary pain and burning from scratching and blistering can occur as well. Common allergens in the genital area include benzocaine, diphenhydramine (Benadryl), neomycin in triple antibiotic ointment (Neosporin), and latex. Allergic contact dermatitis occurs after 1 or 2 weeks of initial exposure or 1 or 2 days after re-exposure.

The diagnosis of an irritant or allergic contact dermatitis can be based on a history of incontinence, application of high-risk substances, or inappropriate washing. Management generally involves discontinuation of all panty liners and topical agents except for water, with a topical steroid ointment used twice a day and pure petroleum jelly used as often as necessary for comfort. Nighttime sedation to allow a reprieve from rubbing and scratching may be helpful, and narcotic pain medications may be useful for the first 1 to 2 weeks of treatment.

Women who fail to respond to treatment should be referred for patch testing by a

dermatologist.

Related article: Vulvar pain syndromes: Making the correct diagnosis. Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH; Libby Edwards, MD; Jennifer Gunter, MD; Hope K. Haefner, MD (Roundtable, part 1 of 3; September 2011)

CASE 3. TEENAGER WITH VULVAR PAIN AND SORES

A woman brings her 13-year-old daughter to your office for treatment of sudden-onset vulvar pain and sores. The child developed a sore throat and low-grade fever 3 days earlier, with vulvar pain and vulvar dysuria the next day. The pediatrician diagnosed a herpes simplex virus infection and prescribed oral acyclovir, but the girl’s condition has not improved, and the mother believes her daughter’s claims of sexual abstinence.

The girl is otherwise healthy, aside from a history of trivial oral canker sores without arthritis, headaches, abdominal pain, eye pain, or vision changes.

Physical examination of the vulva reveals soft, painful, well-demarcated ulcers with a white fibrin base (FIGURE 3).

Diagnosis: Complex aphthosis. Further testing is unnecessary.

Treatment: Prednisone 40 mg/day plus hydrocodone in usual doses of 5/325, one or two tablets every 4 to 6 hours, as needed; topical petroleum jelly (especially before urination); and sitz baths. When the patient returns 1 week later, she is much improved.

Aphthae are believed to be of hyperimmune origin, often precipitated by a viral syndrome. They are most common in girls aged 9 to 18 years. Vulvar aphthae are triggered by various viral infections, including Epstein-Barr.2 The offending virus is not located in the ulcer proper, however, but is identified serologically.

Aphthae are uncommon and under-recognized on the vulva, and genital aphthae are usually much larger than oral aphthae. Most patients initially are mistakenly evaluated and treated for sexually transmitted disease, but the large, well-demarcated, painful, nonindurated deep nature of the ulcer is pathognomonic for an aphthous ulcer.

The presence of oral and genital aphthae does not constitute a diagnosis of Behçet disease, an often-devastating systemic inflammatory condition occurring almost exclusively in men in the Middle and Far East. The diagnosis of Behçet disease requires the identification of objective inflammatory disease of the eyes, joints, gastrointestinal tract, or neurologic system. True Behçet disease is incredibly uncommon in the United States. When it is diagnosed in Western countries, it takes an attenuated form, most often occurring in women who experience multisystem discomfort rather than identifiable inflammatory disease. End-organ damage is uncommon. Evaluation for Behçet disease in women with vulvar aphthae generally is not indicated, although a directed review of systems is reasonable. The rare patient who experiences frequent recurrence and symptoms of systemic disease should be referred to an ophthalmologist and other relevant specialists to evaluate for inflammatory disease.

The treatment of vulvar aphthae consists of systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone 40 mg/day for smaller individuals and 60 mg/day for larger women, with follow-up to ensure a good response. Often, the prednisone can be discontinued when pain relents rather than continued through complete healing. Reassurance, without discussing Behçet disease, is paramount, as is pain control. The heavy application of petroleum jelly can decrease pain and prevent urine from touching the ulcer.

Some patients experience recurrent ulcers. A second prescription of prednisone can be provided for immediate reinstitution with onset of symptoms. However, frequent recurrences may require ongoing suppressive medication, with dapsone being the usual first choice. Colchicine often is used, and thalidomide and tumor necrosis factor-a blockers (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) also are extremely beneficial.3,4

CASE 4. INCREASED NEUTROPHILS AND NO LACTOBACILLI

A 36-year-old woman visits your office reporting introital itching, vulvar dysuria, and superficial dyspareunia that have lasted 6 months. She has tried over-the-counter antifungal therapy, with only slight improvement while using the cream. Her health is normal otherwise, lacking pain syndromes or abnormalities suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction. She experienced comfortable sexual activity until 6 months ago.

The only abnormalities apparent on physical examination are redness of the vestibule, medial labia minora, and vaginal walls, with edema of the surrounding skin and no oral lesions (FIGURE 4A). Copious vaginal secretions are visible at the introitus. A wet mount shows a marked increase in neutrophils with scattered parabasal cells (FIGURE 4B). There are no clue cells, lactobacilli, or yeast forms. The patient’s pH level is greater than 6.5. Routine and fungal cultures and molecular studies for chlamydia, trichomonas, and gonorrhea are returned as normal.

Diagnosis: Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

Treatment: Clindamycin vaginal cream, 1/2 to 1 full applicator nightly, with a weekly oral fluconazole tablet (200 mg is more easily covered by insurance) to prevent secondary candidiasis. You schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) is described as noninfectious inflammatory vaginitis in a setting of normal estrogen and absence of skin disease of the mucous membranes of the vagina. The condition is characterized by an increase in white blood cells and parabasal cells, and absent lactobacilli, with relatively high vaginal pH. DIV is thought to represent an inflammatory dermatosis of the vaginal epithelium.5 Although some clinicians believe that DIV is actually lichen planus, the latter exhibits erosions as well as redness, nearly always affects the mouth and the vulva, and produces remarkable scarring. DIV does not erode, affect any other skin surfaces, or scar.

Other rare skin diseases that produce erosions and scarring also can be ruled out by the presence of erosions, absence of oral disease, and absence of other mucosal involvement. These diseases include cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Infectious diseases characterized by inflammation are excluded by culture or molecular studies, and atrophic vaginitis and retained foreign bodies (especially retained tampons) can produce a similar picture.

The vulvar itching and irritation that occur with DIV most likely represent an irritant contact dermatitis, with vaginal secretions serving as the irritant.

How to treat DIV

The management of DIV consists of either topical clindamycin cream (theoretically for its anti-inflammatory rather than antimicrobial properties) or intravaginal corticosteroids, especially hydrocortisone acetate.6 Hydrocortisone can be tried at the low commercially available dose of 25-mg rectal suppositories, which should be inserted into the vagina nightly, or it can be compounded at 100 or 200 mg, if needed. If the condition is recalcitrant, combination therapy can be used.

When signs and symptoms abate, the frequency of use can be decreased, or hydrocortisone can be discontinued and restarted again with any recurrence of discomfort. Many clinicians also prescribe weekly fluconazole to prevent intercurrent candidiasis.

Related article: Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis. Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, July 2013)

CASE 5. PLAQUES ON VULVA AND IN SKIN FOLDS

A 43-year-old woman reports a recalcitrant yeast infection of the vulva, with itching and irritation. She is overweight and diabetic, with mild stress incontinence.

Physical examination reveals a fairly well-demarcated plaque of redness of the vulva and labiocrural folds, with satellite red papules and peripheral peeling (FIGURE 5). An examination of other skin surfaces reveals similar plaques in the gluteal cleft, umbilicus, and axillae as well as under the breasts. A fungal preparation of the vagina and skin is negative. You obtain a fungal culture and prescribe topical and oral antifungal therapy and see the patient again 1 week later. Her condition is unchanged.

Diagnosis: You make a presumptive diagnosis of inverse psoriasis and do a confirmatory punch biopsy.

Treatment: Clobetasol ointment applied to the skin folds, along with continuation of the topical miconazole cream. A week later, the patient’s condition is remarkably improved, and her biopsy shows psoriasiform dermatitis. You reduce the potency of her corticosteroid, switching to desonide cream sparingly applied daily.

Psoriasis is a common skin disease of immunologic origin. The skin is classically red and thick, with heavy white scale produced by rapid turnover of epithelium. However, there are several morphologic types of psoriasis, and anogenital psoriasis is most often of the inverse pattern. Inverse psoriasis preferentially affects skin folds and is frequently mistaken for (and often initially superinfected with) candidiasis. Scale is thin and unapparent, and there often is a shiny, glazed appearance to the skin. Tiny satellite lesions often are visible as well. A skin biopsy of inverse psoriasis often is not diagnostic, showing only nonspecific psoriasiform dermatitis; this does not disprove psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a systemic condition and is associated with metabolic syndrome, carrying an increased risk of overweight, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Management of these conditions is very important in the treatment of the patient overall.

Unlike lichen planus and lichen sclerosus, scarring is rare with psoriasis, and squamous cell carcinoma generally is unassociated.7,8

Anogenital psoriasis is treated with topical corticosteroids and, when needed, topical vitamin D preparations. Generally, inverse psoriasis is controlled with low-potency topical corticosteroids, with management of secondary infection and irritants. Otherwise, ultraviolet light is a time-honored therapy for psoriasis but not practical for skin folds. It also is difficult for many patients to manage with a busy life. Systemic therapy, including methotrexate and oral retinoids are often used, as are newer biologic agents such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article or on any topic relevant to ObGyns and women’s health practitioners. Tell us which topics you’d like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. We will consider publishing your letter and in a future issue. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice. Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman ML. Resistance and barriers to local estrogen therapy in women with atrophic vaginitis.

J Sex Med. 2013;10(6):1567–1574. - Huppert JS, Gerber MA, Deitch HR, et al. Vulvar ulcers in young females: A manifestation of aphthosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19(3):195–204.

- O’Neill ID. Efficacy of tumour necrosis factor-a antagonists in aphthous ulceration: Review of published individual patient data. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(2):231–235.

- Sanchez-Cano D, Callejas-Rubio JL, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Ortego-Centeno N. Recalcitrant, recurrent aphthous stomatitis successfully treated with adalimumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(2):206.

- Stockdale CK. Clinical spectrum of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(6):479–483.

- Sobel JD, Reichman O, Misra D, Yoo W. Prognosis and treatment of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):850–855.

- Albert S, Neill S, Derrick EK, Calonje E. Psoriasis associated with vulvar scarring. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(4):354–356.

- Boffetta P, Gridley G, Lindelöf B. Cancer risk in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized for psoriasis in Sweden. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(6):1531–1537.

Chronic irritation, itching, and pain are only rarely due to infection. These symptoms are more likely to be caused by dermatoses, vaginal abnormalities, and pain syndromes that may be difficult to diagnose. Careful evaluation should include a wet mount and culture to eliminate infection as a cause so that the correct diagnosis can be ascertained and treated.

In Part 2 of this two-part series, we focus on five cases of vulvar dermatologic disruptions:

- atrophic vagina

- irritant and allergic contact dermatitis

- complex vulvar aphthosis

- desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

- inverse psoriasis.

CASE 1. INTROITAL BURNING AND A FEAR OF BREAST CANCER

A 56-year-old woman visits your office for management of recent-onset introital burning during sexual activity. She reports that her commercial lubricant causes irritation. Topical and oral antifungal therapies have not been beneficial. She has a strong family history of breast cancer.

On examination, she exhibits small, smooth labia minora and experiences pain when a cotton swab is pressed against the vestibule. The vagina is also smooth, with scant secretions. Microscopically, these secretions are almost acellular, with no increase in white blood cells and no clue cells, yeast forms, or lactobacilli. The pH is greater than 6.5, and most epithelial cells are parabasal (FIGURE 1).

You prescribe topical estradiol cream for vaginal use three nights per week, but when the patient returns 1 month later, her condition is unchanged. She explains that she never used the cream after reading the package insert, which reports a risk of breast cancer.

Diagnosis: Atrophic vagina (not atrophic vaginitis, as there is no increase in white blood cells).

Treatment: Re-estrogenization should relieve her symptoms.

Several options for local estrogen replacement are available. Creams include estradiol (Estrace) and conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin), the latter of which is arguably slightly more irritating. These are prescribed at a starting dose of 1 g in the vagina three nights per week. After several weeks, they can be titrated to the lowest frequency that controls symptoms.

The risk of vaginal candidiasis is fairly high during the first 2 or 3 weeks of re-estrogenization, so patients should be warned of this possibility. Also consider prophylactic weekly fluconazole or an azole suppository two or three times a week for the first few weeks. Estradiol tablets (Vagifem) inserted in the vagina are effective, less messy, and more expensive, as is the estradiol ring (Estring), which is inserted and changed quarterly.

It is not unusual for a woman to avoid use of topical estrogen out of fear, or to use insufficient amounts only on the vulva, or to use it for only 1 or 2 weeks.1

Women should be scheduled for a return visit to ensure they have been using the estrogen, their wet mount has normalized, and discomfort has cleared.

Related article: Your menopausal patient's breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia. JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD (Cases in Menopause; May 2013)

When a woman is reluctant to use local estrogen

We counsel women that small doses of vaginal estrogen used for limited periods of time are unlikely to influence their breast cancer risk and are the most effective treatment for symptoms of atrophy. Usually, this explanation is sufficient to reassure a woman that topical estrogen is safe. Otherwise, use of commercial personal lubricants (silicone-based lubricants are well tolerated) and moisturizers such as Replens and RePhresh can be comforting.

The topical anesthetics lidocaine 2% jelly or lidocaine 5% ointment (which sometimes burns) can minimize pain with sexual activity for those requiring more than lubrication.

Ospemifene (Osphena) is used by some clinicians in this situation, but this medication is labeled as a risk for all of the same contraindications as systemic estrogen, and it is much more expensive than topical estrogen. Ospemifene is an estrogen agonist/antagonist. Although it is the only oral medication indicated for the treatment of menopause-related dyspareunia, the long-term effects on breast cancer risk are unknown. Also, it has an agonist effect on the endometrium and, again, the long-term risk is unknown.

Related article: New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (News for your Practice; May 2013)

Fluconazole use is contraindicated with ospemifene, as is the use of any estrogen products.

CASE 2. RECALCITRANT ITCHING, BURNING, AND REDNESS

A 25-year-old woman reports anogenital itching, burning, and redness, which have been present for 3 months. She says she developed a yeast infection after antibiotic therapy for a dental infection; the yeast infection was treated with terconazole. She reports an allergic reaction to the terconazole, with immediate severe burning, redness, and swelling. The clobetasol cream she was given to use twice daily also caused burning, so she discontinued it. Her symptoms improved when she tried cool soaks and applied topical benzocaine gel as a local anesthetic. However,

2 weeks later, she experienced increasing redness, itching, and burning. Although the benzocaine relieved these symptoms, it required almost continual reapplication for comfort.

A physical examination of the vulva reveals generalized, poorly demarcated redness, edema, and superficial erosions (FIGURE 2).

Diagnosis: Irritant contact dermatitis (as opposed to allergic contact dermatitis) associated with the use of terconazole and clobetasol. This was followed by allergic contact dermatitis in association with benzocaine.

Treatment: Withdrawal of benzocaine, with reinitiation of cool soaks and a switch to clobetasol ointment rather than cream. Nighttime sedation allows the patient to sleep through the itching and gradually allows her skin to heal.

Contact dermatitis is a fairly common cause of vulvar irritation, with two main types:

- Irritant contact dermatitis—The most common form, it occurs in any individual exposed to an irritating substance in sufficient quantity or frequency. Irritant contact dermatitis is characterized mostly by sensations of rawness or burning and generally is caused by urine, feces, perspiration, friction, alcohols in topical creams, overwashing, and use of harsh soaps.

- Allergic contact dermatitis—This form is characterized by itching, although secondary pain and burning from scratching and blistering can occur as well. Common allergens in the genital area include benzocaine, diphenhydramine (Benadryl), neomycin in triple antibiotic ointment (Neosporin), and latex. Allergic contact dermatitis occurs after 1 or 2 weeks of initial exposure or 1 or 2 days after re-exposure.

The diagnosis of an irritant or allergic contact dermatitis can be based on a history of incontinence, application of high-risk substances, or inappropriate washing. Management generally involves discontinuation of all panty liners and topical agents except for water, with a topical steroid ointment used twice a day and pure petroleum jelly used as often as necessary for comfort. Nighttime sedation to allow a reprieve from rubbing and scratching may be helpful, and narcotic pain medications may be useful for the first 1 to 2 weeks of treatment.

Women who fail to respond to treatment should be referred for patch testing by a

dermatologist.

Related article: Vulvar pain syndromes: Making the correct diagnosis. Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH; Libby Edwards, MD; Jennifer Gunter, MD; Hope K. Haefner, MD (Roundtable, part 1 of 3; September 2011)

CASE 3. TEENAGER WITH VULVAR PAIN AND SORES

A woman brings her 13-year-old daughter to your office for treatment of sudden-onset vulvar pain and sores. The child developed a sore throat and low-grade fever 3 days earlier, with vulvar pain and vulvar dysuria the next day. The pediatrician diagnosed a herpes simplex virus infection and prescribed oral acyclovir, but the girl’s condition has not improved, and the mother believes her daughter’s claims of sexual abstinence.

The girl is otherwise healthy, aside from a history of trivial oral canker sores without arthritis, headaches, abdominal pain, eye pain, or vision changes.

Physical examination of the vulva reveals soft, painful, well-demarcated ulcers with a white fibrin base (FIGURE 3).

Diagnosis: Complex aphthosis. Further testing is unnecessary.

Treatment: Prednisone 40 mg/day plus hydrocodone in usual doses of 5/325, one or two tablets every 4 to 6 hours, as needed; topical petroleum jelly (especially before urination); and sitz baths. When the patient returns 1 week later, she is much improved.

Aphthae are believed to be of hyperimmune origin, often precipitated by a viral syndrome. They are most common in girls aged 9 to 18 years. Vulvar aphthae are triggered by various viral infections, including Epstein-Barr.2 The offending virus is not located in the ulcer proper, however, but is identified serologically.

Aphthae are uncommon and under-recognized on the vulva, and genital aphthae are usually much larger than oral aphthae. Most patients initially are mistakenly evaluated and treated for sexually transmitted disease, but the large, well-demarcated, painful, nonindurated deep nature of the ulcer is pathognomonic for an aphthous ulcer.

The presence of oral and genital aphthae does not constitute a diagnosis of Behçet disease, an often-devastating systemic inflammatory condition occurring almost exclusively in men in the Middle and Far East. The diagnosis of Behçet disease requires the identification of objective inflammatory disease of the eyes, joints, gastrointestinal tract, or neurologic system. True Behçet disease is incredibly uncommon in the United States. When it is diagnosed in Western countries, it takes an attenuated form, most often occurring in women who experience multisystem discomfort rather than identifiable inflammatory disease. End-organ damage is uncommon. Evaluation for Behçet disease in women with vulvar aphthae generally is not indicated, although a directed review of systems is reasonable. The rare patient who experiences frequent recurrence and symptoms of systemic disease should be referred to an ophthalmologist and other relevant specialists to evaluate for inflammatory disease.

The treatment of vulvar aphthae consists of systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone 40 mg/day for smaller individuals and 60 mg/day for larger women, with follow-up to ensure a good response. Often, the prednisone can be discontinued when pain relents rather than continued through complete healing. Reassurance, without discussing Behçet disease, is paramount, as is pain control. The heavy application of petroleum jelly can decrease pain and prevent urine from touching the ulcer.

Some patients experience recurrent ulcers. A second prescription of prednisone can be provided for immediate reinstitution with onset of symptoms. However, frequent recurrences may require ongoing suppressive medication, with dapsone being the usual first choice. Colchicine often is used, and thalidomide and tumor necrosis factor-a blockers (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) also are extremely beneficial.3,4

CASE 4. INCREASED NEUTROPHILS AND NO LACTOBACILLI

A 36-year-old woman visits your office reporting introital itching, vulvar dysuria, and superficial dyspareunia that have lasted 6 months. She has tried over-the-counter antifungal therapy, with only slight improvement while using the cream. Her health is normal otherwise, lacking pain syndromes or abnormalities suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction. She experienced comfortable sexual activity until 6 months ago.

The only abnormalities apparent on physical examination are redness of the vestibule, medial labia minora, and vaginal walls, with edema of the surrounding skin and no oral lesions (FIGURE 4A). Copious vaginal secretions are visible at the introitus. A wet mount shows a marked increase in neutrophils with scattered parabasal cells (FIGURE 4B). There are no clue cells, lactobacilli, or yeast forms. The patient’s pH level is greater than 6.5. Routine and fungal cultures and molecular studies for chlamydia, trichomonas, and gonorrhea are returned as normal.

Diagnosis: Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

Treatment: Clindamycin vaginal cream, 1/2 to 1 full applicator nightly, with a weekly oral fluconazole tablet (200 mg is more easily covered by insurance) to prevent secondary candidiasis. You schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) is described as noninfectious inflammatory vaginitis in a setting of normal estrogen and absence of skin disease of the mucous membranes of the vagina. The condition is characterized by an increase in white blood cells and parabasal cells, and absent lactobacilli, with relatively high vaginal pH. DIV is thought to represent an inflammatory dermatosis of the vaginal epithelium.5 Although some clinicians believe that DIV is actually lichen planus, the latter exhibits erosions as well as redness, nearly always affects the mouth and the vulva, and produces remarkable scarring. DIV does not erode, affect any other skin surfaces, or scar.

Other rare skin diseases that produce erosions and scarring also can be ruled out by the presence of erosions, absence of oral disease, and absence of other mucosal involvement. These diseases include cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Infectious diseases characterized by inflammation are excluded by culture or molecular studies, and atrophic vaginitis and retained foreign bodies (especially retained tampons) can produce a similar picture.

The vulvar itching and irritation that occur with DIV most likely represent an irritant contact dermatitis, with vaginal secretions serving as the irritant.

How to treat DIV

The management of DIV consists of either topical clindamycin cream (theoretically for its anti-inflammatory rather than antimicrobial properties) or intravaginal corticosteroids, especially hydrocortisone acetate.6 Hydrocortisone can be tried at the low commercially available dose of 25-mg rectal suppositories, which should be inserted into the vagina nightly, or it can be compounded at 100 or 200 mg, if needed. If the condition is recalcitrant, combination therapy can be used.

When signs and symptoms abate, the frequency of use can be decreased, or hydrocortisone can be discontinued and restarted again with any recurrence of discomfort. Many clinicians also prescribe weekly fluconazole to prevent intercurrent candidiasis.

Related article: Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis. Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, July 2013)

CASE 5. PLAQUES ON VULVA AND IN SKIN FOLDS

A 43-year-old woman reports a recalcitrant yeast infection of the vulva, with itching and irritation. She is overweight and diabetic, with mild stress incontinence.

Physical examination reveals a fairly well-demarcated plaque of redness of the vulva and labiocrural folds, with satellite red papules and peripheral peeling (FIGURE 5). An examination of other skin surfaces reveals similar plaques in the gluteal cleft, umbilicus, and axillae as well as under the breasts. A fungal preparation of the vagina and skin is negative. You obtain a fungal culture and prescribe topical and oral antifungal therapy and see the patient again 1 week later. Her condition is unchanged.

Diagnosis: You make a presumptive diagnosis of inverse psoriasis and do a confirmatory punch biopsy.

Treatment: Clobetasol ointment applied to the skin folds, along with continuation of the topical miconazole cream. A week later, the patient’s condition is remarkably improved, and her biopsy shows psoriasiform dermatitis. You reduce the potency of her corticosteroid, switching to desonide cream sparingly applied daily.

Psoriasis is a common skin disease of immunologic origin. The skin is classically red and thick, with heavy white scale produced by rapid turnover of epithelium. However, there are several morphologic types of psoriasis, and anogenital psoriasis is most often of the inverse pattern. Inverse psoriasis preferentially affects skin folds and is frequently mistaken for (and often initially superinfected with) candidiasis. Scale is thin and unapparent, and there often is a shiny, glazed appearance to the skin. Tiny satellite lesions often are visible as well. A skin biopsy of inverse psoriasis often is not diagnostic, showing only nonspecific psoriasiform dermatitis; this does not disprove psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a systemic condition and is associated with metabolic syndrome, carrying an increased risk of overweight, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Management of these conditions is very important in the treatment of the patient overall.

Unlike lichen planus and lichen sclerosus, scarring is rare with psoriasis, and squamous cell carcinoma generally is unassociated.7,8

Anogenital psoriasis is treated with topical corticosteroids and, when needed, topical vitamin D preparations. Generally, inverse psoriasis is controlled with low-potency topical corticosteroids, with management of secondary infection and irritants. Otherwise, ultraviolet light is a time-honored therapy for psoriasis but not practical for skin folds. It also is difficult for many patients to manage with a busy life. Systemic therapy, including methotrexate and oral retinoids are often used, as are newer biologic agents such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article or on any topic relevant to ObGyns and women’s health practitioners. Tell us which topics you’d like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. We will consider publishing your letter and in a future issue. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice. Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

Chronic irritation, itching, and pain are only rarely due to infection. These symptoms are more likely to be caused by dermatoses, vaginal abnormalities, and pain syndromes that may be difficult to diagnose. Careful evaluation should include a wet mount and culture to eliminate infection as a cause so that the correct diagnosis can be ascertained and treated.

In Part 2 of this two-part series, we focus on five cases of vulvar dermatologic disruptions:

- atrophic vagina

- irritant and allergic contact dermatitis

- complex vulvar aphthosis

- desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

- inverse psoriasis.

CASE 1. INTROITAL BURNING AND A FEAR OF BREAST CANCER

A 56-year-old woman visits your office for management of recent-onset introital burning during sexual activity. She reports that her commercial lubricant causes irritation. Topical and oral antifungal therapies have not been beneficial. She has a strong family history of breast cancer.

On examination, she exhibits small, smooth labia minora and experiences pain when a cotton swab is pressed against the vestibule. The vagina is also smooth, with scant secretions. Microscopically, these secretions are almost acellular, with no increase in white blood cells and no clue cells, yeast forms, or lactobacilli. The pH is greater than 6.5, and most epithelial cells are parabasal (FIGURE 1).

You prescribe topical estradiol cream for vaginal use three nights per week, but when the patient returns 1 month later, her condition is unchanged. She explains that she never used the cream after reading the package insert, which reports a risk of breast cancer.

Diagnosis: Atrophic vagina (not atrophic vaginitis, as there is no increase in white blood cells).

Treatment: Re-estrogenization should relieve her symptoms.

Several options for local estrogen replacement are available. Creams include estradiol (Estrace) and conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin), the latter of which is arguably slightly more irritating. These are prescribed at a starting dose of 1 g in the vagina three nights per week. After several weeks, they can be titrated to the lowest frequency that controls symptoms.

The risk of vaginal candidiasis is fairly high during the first 2 or 3 weeks of re-estrogenization, so patients should be warned of this possibility. Also consider prophylactic weekly fluconazole or an azole suppository two or three times a week for the first few weeks. Estradiol tablets (Vagifem) inserted in the vagina are effective, less messy, and more expensive, as is the estradiol ring (Estring), which is inserted and changed quarterly.

It is not unusual for a woman to avoid use of topical estrogen out of fear, or to use insufficient amounts only on the vulva, or to use it for only 1 or 2 weeks.1

Women should be scheduled for a return visit to ensure they have been using the estrogen, their wet mount has normalized, and discomfort has cleared.

Related article: Your menopausal patient's breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia. JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD (Cases in Menopause; May 2013)

When a woman is reluctant to use local estrogen

We counsel women that small doses of vaginal estrogen used for limited periods of time are unlikely to influence their breast cancer risk and are the most effective treatment for symptoms of atrophy. Usually, this explanation is sufficient to reassure a woman that topical estrogen is safe. Otherwise, use of commercial personal lubricants (silicone-based lubricants are well tolerated) and moisturizers such as Replens and RePhresh can be comforting.

The topical anesthetics lidocaine 2% jelly or lidocaine 5% ointment (which sometimes burns) can minimize pain with sexual activity for those requiring more than lubrication.

Ospemifene (Osphena) is used by some clinicians in this situation, but this medication is labeled as a risk for all of the same contraindications as systemic estrogen, and it is much more expensive than topical estrogen. Ospemifene is an estrogen agonist/antagonist. Although it is the only oral medication indicated for the treatment of menopause-related dyspareunia, the long-term effects on breast cancer risk are unknown. Also, it has an agonist effect on the endometrium and, again, the long-term risk is unknown.

Related article: New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (News for your Practice; May 2013)

Fluconazole use is contraindicated with ospemifene, as is the use of any estrogen products.

CASE 2. RECALCITRANT ITCHING, BURNING, AND REDNESS

A 25-year-old woman reports anogenital itching, burning, and redness, which have been present for 3 months. She says she developed a yeast infection after antibiotic therapy for a dental infection; the yeast infection was treated with terconazole. She reports an allergic reaction to the terconazole, with immediate severe burning, redness, and swelling. The clobetasol cream she was given to use twice daily also caused burning, so she discontinued it. Her symptoms improved when she tried cool soaks and applied topical benzocaine gel as a local anesthetic. However,

2 weeks later, she experienced increasing redness, itching, and burning. Although the benzocaine relieved these symptoms, it required almost continual reapplication for comfort.

A physical examination of the vulva reveals generalized, poorly demarcated redness, edema, and superficial erosions (FIGURE 2).

Diagnosis: Irritant contact dermatitis (as opposed to allergic contact dermatitis) associated with the use of terconazole and clobetasol. This was followed by allergic contact dermatitis in association with benzocaine.

Treatment: Withdrawal of benzocaine, with reinitiation of cool soaks and a switch to clobetasol ointment rather than cream. Nighttime sedation allows the patient to sleep through the itching and gradually allows her skin to heal.

Contact dermatitis is a fairly common cause of vulvar irritation, with two main types:

- Irritant contact dermatitis—The most common form, it occurs in any individual exposed to an irritating substance in sufficient quantity or frequency. Irritant contact dermatitis is characterized mostly by sensations of rawness or burning and generally is caused by urine, feces, perspiration, friction, alcohols in topical creams, overwashing, and use of harsh soaps.

- Allergic contact dermatitis—This form is characterized by itching, although secondary pain and burning from scratching and blistering can occur as well. Common allergens in the genital area include benzocaine, diphenhydramine (Benadryl), neomycin in triple antibiotic ointment (Neosporin), and latex. Allergic contact dermatitis occurs after 1 or 2 weeks of initial exposure or 1 or 2 days after re-exposure.

The diagnosis of an irritant or allergic contact dermatitis can be based on a history of incontinence, application of high-risk substances, or inappropriate washing. Management generally involves discontinuation of all panty liners and topical agents except for water, with a topical steroid ointment used twice a day and pure petroleum jelly used as often as necessary for comfort. Nighttime sedation to allow a reprieve from rubbing and scratching may be helpful, and narcotic pain medications may be useful for the first 1 to 2 weeks of treatment.

Women who fail to respond to treatment should be referred for patch testing by a

dermatologist.

Related article: Vulvar pain syndromes: Making the correct diagnosis. Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH; Libby Edwards, MD; Jennifer Gunter, MD; Hope K. Haefner, MD (Roundtable, part 1 of 3; September 2011)

CASE 3. TEENAGER WITH VULVAR PAIN AND SORES

A woman brings her 13-year-old daughter to your office for treatment of sudden-onset vulvar pain and sores. The child developed a sore throat and low-grade fever 3 days earlier, with vulvar pain and vulvar dysuria the next day. The pediatrician diagnosed a herpes simplex virus infection and prescribed oral acyclovir, but the girl’s condition has not improved, and the mother believes her daughter’s claims of sexual abstinence.

The girl is otherwise healthy, aside from a history of trivial oral canker sores without arthritis, headaches, abdominal pain, eye pain, or vision changes.

Physical examination of the vulva reveals soft, painful, well-demarcated ulcers with a white fibrin base (FIGURE 3).

Diagnosis: Complex aphthosis. Further testing is unnecessary.

Treatment: Prednisone 40 mg/day plus hydrocodone in usual doses of 5/325, one or two tablets every 4 to 6 hours, as needed; topical petroleum jelly (especially before urination); and sitz baths. When the patient returns 1 week later, she is much improved.

Aphthae are believed to be of hyperimmune origin, often precipitated by a viral syndrome. They are most common in girls aged 9 to 18 years. Vulvar aphthae are triggered by various viral infections, including Epstein-Barr.2 The offending virus is not located in the ulcer proper, however, but is identified serologically.

Aphthae are uncommon and under-recognized on the vulva, and genital aphthae are usually much larger than oral aphthae. Most patients initially are mistakenly evaluated and treated for sexually transmitted disease, but the large, well-demarcated, painful, nonindurated deep nature of the ulcer is pathognomonic for an aphthous ulcer.

The presence of oral and genital aphthae does not constitute a diagnosis of Behçet disease, an often-devastating systemic inflammatory condition occurring almost exclusively in men in the Middle and Far East. The diagnosis of Behçet disease requires the identification of objective inflammatory disease of the eyes, joints, gastrointestinal tract, or neurologic system. True Behçet disease is incredibly uncommon in the United States. When it is diagnosed in Western countries, it takes an attenuated form, most often occurring in women who experience multisystem discomfort rather than identifiable inflammatory disease. End-organ damage is uncommon. Evaluation for Behçet disease in women with vulvar aphthae generally is not indicated, although a directed review of systems is reasonable. The rare patient who experiences frequent recurrence and symptoms of systemic disease should be referred to an ophthalmologist and other relevant specialists to evaluate for inflammatory disease.

The treatment of vulvar aphthae consists of systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone 40 mg/day for smaller individuals and 60 mg/day for larger women, with follow-up to ensure a good response. Often, the prednisone can be discontinued when pain relents rather than continued through complete healing. Reassurance, without discussing Behçet disease, is paramount, as is pain control. The heavy application of petroleum jelly can decrease pain and prevent urine from touching the ulcer.

Some patients experience recurrent ulcers. A second prescription of prednisone can be provided for immediate reinstitution with onset of symptoms. However, frequent recurrences may require ongoing suppressive medication, with dapsone being the usual first choice. Colchicine often is used, and thalidomide and tumor necrosis factor-a blockers (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) also are extremely beneficial.3,4

CASE 4. INCREASED NEUTROPHILS AND NO LACTOBACILLI

A 36-year-old woman visits your office reporting introital itching, vulvar dysuria, and superficial dyspareunia that have lasted 6 months. She has tried over-the-counter antifungal therapy, with only slight improvement while using the cream. Her health is normal otherwise, lacking pain syndromes or abnormalities suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction. She experienced comfortable sexual activity until 6 months ago.

The only abnormalities apparent on physical examination are redness of the vestibule, medial labia minora, and vaginal walls, with edema of the surrounding skin and no oral lesions (FIGURE 4A). Copious vaginal secretions are visible at the introitus. A wet mount shows a marked increase in neutrophils with scattered parabasal cells (FIGURE 4B). There are no clue cells, lactobacilli, or yeast forms. The patient’s pH level is greater than 6.5. Routine and fungal cultures and molecular studies for chlamydia, trichomonas, and gonorrhea are returned as normal.

Diagnosis: Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

Treatment: Clindamycin vaginal cream, 1/2 to 1 full applicator nightly, with a weekly oral fluconazole tablet (200 mg is more easily covered by insurance) to prevent secondary candidiasis. You schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) is described as noninfectious inflammatory vaginitis in a setting of normal estrogen and absence of skin disease of the mucous membranes of the vagina. The condition is characterized by an increase in white blood cells and parabasal cells, and absent lactobacilli, with relatively high vaginal pH. DIV is thought to represent an inflammatory dermatosis of the vaginal epithelium.5 Although some clinicians believe that DIV is actually lichen planus, the latter exhibits erosions as well as redness, nearly always affects the mouth and the vulva, and produces remarkable scarring. DIV does not erode, affect any other skin surfaces, or scar.

Other rare skin diseases that produce erosions and scarring also can be ruled out by the presence of erosions, absence of oral disease, and absence of other mucosal involvement. These diseases include cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Infectious diseases characterized by inflammation are excluded by culture or molecular studies, and atrophic vaginitis and retained foreign bodies (especially retained tampons) can produce a similar picture.

The vulvar itching and irritation that occur with DIV most likely represent an irritant contact dermatitis, with vaginal secretions serving as the irritant.

How to treat DIV

The management of DIV consists of either topical clindamycin cream (theoretically for its anti-inflammatory rather than antimicrobial properties) or intravaginal corticosteroids, especially hydrocortisone acetate.6 Hydrocortisone can be tried at the low commercially available dose of 25-mg rectal suppositories, which should be inserted into the vagina nightly, or it can be compounded at 100 or 200 mg, if needed. If the condition is recalcitrant, combination therapy can be used.

When signs and symptoms abate, the frequency of use can be decreased, or hydrocortisone can be discontinued and restarted again with any recurrence of discomfort. Many clinicians also prescribe weekly fluconazole to prevent intercurrent candidiasis.

Related article: Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis. Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, July 2013)

CASE 5. PLAQUES ON VULVA AND IN SKIN FOLDS

A 43-year-old woman reports a recalcitrant yeast infection of the vulva, with itching and irritation. She is overweight and diabetic, with mild stress incontinence.

Physical examination reveals a fairly well-demarcated plaque of redness of the vulva and labiocrural folds, with satellite red papules and peripheral peeling (FIGURE 5). An examination of other skin surfaces reveals similar plaques in the gluteal cleft, umbilicus, and axillae as well as under the breasts. A fungal preparation of the vagina and skin is negative. You obtain a fungal culture and prescribe topical and oral antifungal therapy and see the patient again 1 week later. Her condition is unchanged.

Diagnosis: You make a presumptive diagnosis of inverse psoriasis and do a confirmatory punch biopsy.

Treatment: Clobetasol ointment applied to the skin folds, along with continuation of the topical miconazole cream. A week later, the patient’s condition is remarkably improved, and her biopsy shows psoriasiform dermatitis. You reduce the potency of her corticosteroid, switching to desonide cream sparingly applied daily.

Psoriasis is a common skin disease of immunologic origin. The skin is classically red and thick, with heavy white scale produced by rapid turnover of epithelium. However, there are several morphologic types of psoriasis, and anogenital psoriasis is most often of the inverse pattern. Inverse psoriasis preferentially affects skin folds and is frequently mistaken for (and often initially superinfected with) candidiasis. Scale is thin and unapparent, and there often is a shiny, glazed appearance to the skin. Tiny satellite lesions often are visible as well. A skin biopsy of inverse psoriasis often is not diagnostic, showing only nonspecific psoriasiform dermatitis; this does not disprove psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a systemic condition and is associated with metabolic syndrome, carrying an increased risk of overweight, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Management of these conditions is very important in the treatment of the patient overall.

Unlike lichen planus and lichen sclerosus, scarring is rare with psoriasis, and squamous cell carcinoma generally is unassociated.7,8

Anogenital psoriasis is treated with topical corticosteroids and, when needed, topical vitamin D preparations. Generally, inverse psoriasis is controlled with low-potency topical corticosteroids, with management of secondary infection and irritants. Otherwise, ultraviolet light is a time-honored therapy for psoriasis but not practical for skin folds. It also is difficult for many patients to manage with a busy life. Systemic therapy, including methotrexate and oral retinoids are often used, as are newer biologic agents such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article or on any topic relevant to ObGyns and women’s health practitioners. Tell us which topics you’d like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. We will consider publishing your letter and in a future issue. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice. Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman ML. Resistance and barriers to local estrogen therapy in women with atrophic vaginitis.

J Sex Med. 2013;10(6):1567–1574. - Huppert JS, Gerber MA, Deitch HR, et al. Vulvar ulcers in young females: A manifestation of aphthosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19(3):195–204.

- O’Neill ID. Efficacy of tumour necrosis factor-a antagonists in aphthous ulceration: Review of published individual patient data. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(2):231–235.

- Sanchez-Cano D, Callejas-Rubio JL, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Ortego-Centeno N. Recalcitrant, recurrent aphthous stomatitis successfully treated with adalimumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(2):206.

- Stockdale CK. Clinical spectrum of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(6):479–483.

- Sobel JD, Reichman O, Misra D, Yoo W. Prognosis and treatment of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):850–855.

- Albert S, Neill S, Derrick EK, Calonje E. Psoriasis associated with vulvar scarring. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(4):354–356.

- Boffetta P, Gridley G, Lindelöf B. Cancer risk in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized for psoriasis in Sweden. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(6):1531–1537.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman ML. Resistance and barriers to local estrogen therapy in women with atrophic vaginitis.

J Sex Med. 2013;10(6):1567–1574. - Huppert JS, Gerber MA, Deitch HR, et al. Vulvar ulcers in young females: A manifestation of aphthosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19(3):195–204.

- O’Neill ID. Efficacy of tumour necrosis factor-a antagonists in aphthous ulceration: Review of published individual patient data. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(2):231–235.

- Sanchez-Cano D, Callejas-Rubio JL, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Ortego-Centeno N. Recalcitrant, recurrent aphthous stomatitis successfully treated with adalimumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(2):206.

- Stockdale CK. Clinical spectrum of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(6):479–483.

- Sobel JD, Reichman O, Misra D, Yoo W. Prognosis and treatment of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):850–855.

- Albert S, Neill S, Derrick EK, Calonje E. Psoriasis associated with vulvar scarring. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(4):354–356.

- Boffetta P, Gridley G, Lindelöf B. Cancer risk in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized for psoriasis in Sweden. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(6):1531–1537.

Read Part 1: Chronic vulvar symptoms and dermatologic disruptions: How to make the correct diagnosis (May 2014)