User login

Chronic vulvar irritation, itching, and pain. What is the diagnosis?

Chronic irritation, itching, and pain are only rarely due to infection. These symptoms are more likely to be caused by dermatoses, vaginal abnormalities, and pain syndromes that may be difficult to diagnose. Careful evaluation should include a wet mount and culture to eliminate infection as a cause so that the correct diagnosis can be ascertained and treated.

In Part 2 of this two-part series, we focus on five cases of vulvar dermatologic disruptions:

- atrophic vagina

- irritant and allergic contact dermatitis

- complex vulvar aphthosis

- desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

- inverse psoriasis.

CASE 1. INTROITAL BURNING AND A FEAR OF BREAST CANCER

A 56-year-old woman visits your office for management of recent-onset introital burning during sexual activity. She reports that her commercial lubricant causes irritation. Topical and oral antifungal therapies have not been beneficial. She has a strong family history of breast cancer.

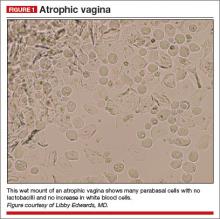

On examination, she exhibits small, smooth labia minora and experiences pain when a cotton swab is pressed against the vestibule. The vagina is also smooth, with scant secretions. Microscopically, these secretions are almost acellular, with no increase in white blood cells and no clue cells, yeast forms, or lactobacilli. The pH is greater than 6.5, and most epithelial cells are parabasal (FIGURE 1).

You prescribe topical estradiol cream for vaginal use three nights per week, but when the patient returns 1 month later, her condition is unchanged. She explains that she never used the cream after reading the package insert, which reports a risk of breast cancer.

Diagnosis: Atrophic vagina (not atrophic vaginitis, as there is no increase in white blood cells).

Treatment: Re-estrogenization should relieve her symptoms.

Several options for local estrogen replacement are available. Creams include estradiol (Estrace) and conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin), the latter of which is arguably slightly more irritating. These are prescribed at a starting dose of 1 g in the vagina three nights per week. After several weeks, they can be titrated to the lowest frequency that controls symptoms.

The risk of vaginal candidiasis is fairly high during the first 2 or 3 weeks of re-estrogenization, so patients should be warned of this possibility. Also consider prophylactic weekly fluconazole or an azole suppository two or three times a week for the first few weeks. Estradiol tablets (Vagifem) inserted in the vagina are effective, less messy, and more expensive, as is the estradiol ring (Estring), which is inserted and changed quarterly.

It is not unusual for a woman to avoid use of topical estrogen out of fear, or to use insufficient amounts only on the vulva, or to use it for only 1 or 2 weeks.1

Women should be scheduled for a return visit to ensure they have been using the estrogen, their wet mount has normalized, and discomfort has cleared.

Related article: Your menopausal patient's breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia. JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD (Cases in Menopause; May 2013)

When a woman is reluctant to use local estrogen

We counsel women that small doses of vaginal estrogen used for limited periods of time are unlikely to influence their breast cancer risk and are the most effective treatment for symptoms of atrophy. Usually, this explanation is sufficient to reassure a woman that topical estrogen is safe. Otherwise, use of commercial personal lubricants (silicone-based lubricants are well tolerated) and moisturizers such as Replens and RePhresh can be comforting.

The topical anesthetics lidocaine 2% jelly or lidocaine 5% ointment (which sometimes burns) can minimize pain with sexual activity for those requiring more than lubrication.

Ospemifene (Osphena) is used by some clinicians in this situation, but this medication is labeled as a risk for all of the same contraindications as systemic estrogen, and it is much more expensive than topical estrogen. Ospemifene is an estrogen agonist/antagonist. Although it is the only oral medication indicated for the treatment of menopause-related dyspareunia, the long-term effects on breast cancer risk are unknown. Also, it has an agonist effect on the endometrium and, again, the long-term risk is unknown.

Related article: New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (News for your Practice; May 2013)

Fluconazole use is contraindicated with ospemifene, as is the use of any estrogen products.

CASE 2. RECALCITRANT ITCHING, BURNING, AND REDNESS

A 25-year-old woman reports anogenital itching, burning, and redness, which have been present for 3 months. She says she developed a yeast infection after antibiotic therapy for a dental infection; the yeast infection was treated with terconazole. She reports an allergic reaction to the terconazole, with immediate severe burning, redness, and swelling. The clobetasol cream she was given to use twice daily also caused burning, so she discontinued it. Her symptoms improved when she tried cool soaks and applied topical benzocaine gel as a local anesthetic. However,

2 weeks later, she experienced increasing redness, itching, and burning. Although the benzocaine relieved these symptoms, it required almost continual reapplication for comfort.

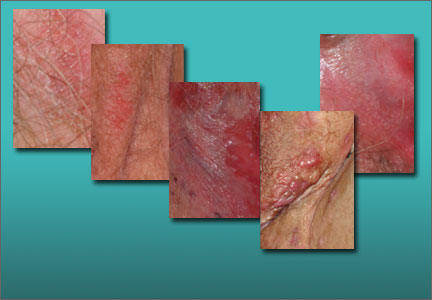

A physical examination of the vulva reveals generalized, poorly demarcated redness, edema, and superficial erosions (FIGURE 2).

Diagnosis: Irritant contact dermatitis (as opposed to allergic contact dermatitis) associated with the use of terconazole and clobetasol. This was followed by allergic contact dermatitis in association with benzocaine.

Treatment: Withdrawal of benzocaine, with reinitiation of cool soaks and a switch to clobetasol ointment rather than cream. Nighttime sedation allows the patient to sleep through the itching and gradually allows her skin to heal.

Contact dermatitis is a fairly common cause of vulvar irritation, with two main types:

- Irritant contact dermatitis—The most common form, it occurs in any individual exposed to an irritating substance in sufficient quantity or frequency. Irritant contact dermatitis is characterized mostly by sensations of rawness or burning and generally is caused by urine, feces, perspiration, friction, alcohols in topical creams, overwashing, and use of harsh soaps.

- Allergic contact dermatitis—This form is characterized by itching, although secondary pain and burning from scratching and blistering can occur as well. Common allergens in the genital area include benzocaine, diphenhydramine (Benadryl), neomycin in triple antibiotic ointment (Neosporin), and latex. Allergic contact dermatitis occurs after 1 or 2 weeks of initial exposure or 1 or 2 days after re-exposure.

The diagnosis of an irritant or allergic contact dermatitis can be based on a history of incontinence, application of high-risk substances, or inappropriate washing. Management generally involves discontinuation of all panty liners and topical agents except for water, with a topical steroid ointment used twice a day and pure petroleum jelly used as often as necessary for comfort. Nighttime sedation to allow a reprieve from rubbing and scratching may be helpful, and narcotic pain medications may be useful for the first 1 to 2 weeks of treatment.

Women who fail to respond to treatment should be referred for patch testing by a

dermatologist.

Related article: Vulvar pain syndromes: Making the correct diagnosis. Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH; Libby Edwards, MD; Jennifer Gunter, MD; Hope K. Haefner, MD (Roundtable, part 1 of 3; September 2011)

CASE 3. TEENAGER WITH VULVAR PAIN AND SORES

A woman brings her 13-year-old daughter to your office for treatment of sudden-onset vulvar pain and sores. The child developed a sore throat and low-grade fever 3 days earlier, with vulvar pain and vulvar dysuria the next day. The pediatrician diagnosed a herpes simplex virus infection and prescribed oral acyclovir, but the girl’s condition has not improved, and the mother believes her daughter’s claims of sexual abstinence.

The girl is otherwise healthy, aside from a history of trivial oral canker sores without arthritis, headaches, abdominal pain, eye pain, or vision changes.

Physical examination of the vulva reveals soft, painful, well-demarcated ulcers with a white fibrin base (FIGURE 3).

Diagnosis: Complex aphthosis. Further testing is unnecessary.

Treatment: Prednisone 40 mg/day plus hydrocodone in usual doses of 5/325, one or two tablets every 4 to 6 hours, as needed; topical petroleum jelly (especially before urination); and sitz baths. When the patient returns 1 week later, she is much improved.

Aphthae are believed to be of hyperimmune origin, often precipitated by a viral syndrome. They are most common in girls aged 9 to 18 years. Vulvar aphthae are triggered by various viral infections, including Epstein-Barr.2 The offending virus is not located in the ulcer proper, however, but is identified serologically.

Aphthae are uncommon and under-recognized on the vulva, and genital aphthae are usually much larger than oral aphthae. Most patients initially are mistakenly evaluated and treated for sexually transmitted disease, but the large, well-demarcated, painful, nonindurated deep nature of the ulcer is pathognomonic for an aphthous ulcer.

The presence of oral and genital aphthae does not constitute a diagnosis of Behçet disease, an often-devastating systemic inflammatory condition occurring almost exclusively in men in the Middle and Far East. The diagnosis of Behçet disease requires the identification of objective inflammatory disease of the eyes, joints, gastrointestinal tract, or neurologic system. True Behçet disease is incredibly uncommon in the United States. When it is diagnosed in Western countries, it takes an attenuated form, most often occurring in women who experience multisystem discomfort rather than identifiable inflammatory disease. End-organ damage is uncommon. Evaluation for Behçet disease in women with vulvar aphthae generally is not indicated, although a directed review of systems is reasonable. The rare patient who experiences frequent recurrence and symptoms of systemic disease should be referred to an ophthalmologist and other relevant specialists to evaluate for inflammatory disease.

The treatment of vulvar aphthae consists of systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone 40 mg/day for smaller individuals and 60 mg/day for larger women, with follow-up to ensure a good response. Often, the prednisone can be discontinued when pain relents rather than continued through complete healing. Reassurance, without discussing Behçet disease, is paramount, as is pain control. The heavy application of petroleum jelly can decrease pain and prevent urine from touching the ulcer.

Some patients experience recurrent ulcers. A second prescription of prednisone can be provided for immediate reinstitution with onset of symptoms. However, frequent recurrences may require ongoing suppressive medication, with dapsone being the usual first choice. Colchicine often is used, and thalidomide and tumor necrosis factor-a blockers (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) also are extremely beneficial.3,4

CASE 4. INCREASED NEUTROPHILS AND NO LACTOBACILLI

A 36-year-old woman visits your office reporting introital itching, vulvar dysuria, and superficial dyspareunia that have lasted 6 months. She has tried over-the-counter antifungal therapy, with only slight improvement while using the cream. Her health is normal otherwise, lacking pain syndromes or abnormalities suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction. She experienced comfortable sexual activity until 6 months ago.

The only abnormalities apparent on physical examination are redness of the vestibule, medial labia minora, and vaginal walls, with edema of the surrounding skin and no oral lesions (FIGURE 4A). Copious vaginal secretions are visible at the introitus. A wet mount shows a marked increase in neutrophils with scattered parabasal cells (FIGURE 4B). There are no clue cells, lactobacilli, or yeast forms. The patient’s pH level is greater than 6.5. Routine and fungal cultures and molecular studies for chlamydia, trichomonas, and gonorrhea are returned as normal.

Diagnosis: Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

Treatment: Clindamycin vaginal cream, 1/2 to 1 full applicator nightly, with a weekly oral fluconazole tablet (200 mg is more easily covered by insurance) to prevent secondary candidiasis. You schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) is described as noninfectious inflammatory vaginitis in a setting of normal estrogen and absence of skin disease of the mucous membranes of the vagina. The condition is characterized by an increase in white blood cells and parabasal cells, and absent lactobacilli, with relatively high vaginal pH. DIV is thought to represent an inflammatory dermatosis of the vaginal epithelium.5 Although some clinicians believe that DIV is actually lichen planus, the latter exhibits erosions as well as redness, nearly always affects the mouth and the vulva, and produces remarkable scarring. DIV does not erode, affect any other skin surfaces, or scar.

Other rare skin diseases that produce erosions and scarring also can be ruled out by the presence of erosions, absence of oral disease, and absence of other mucosal involvement. These diseases include cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Infectious diseases characterized by inflammation are excluded by culture or molecular studies, and atrophic vaginitis and retained foreign bodies (especially retained tampons) can produce a similar picture.

The vulvar itching and irritation that occur with DIV most likely represent an irritant contact dermatitis, with vaginal secretions serving as the irritant.

How to treat DIV

The management of DIV consists of either topical clindamycin cream (theoretically for its anti-inflammatory rather than antimicrobial properties) or intravaginal corticosteroids, especially hydrocortisone acetate.6 Hydrocortisone can be tried at the low commercially available dose of 25-mg rectal suppositories, which should be inserted into the vagina nightly, or it can be compounded at 100 or 200 mg, if needed. If the condition is recalcitrant, combination therapy can be used.

When signs and symptoms abate, the frequency of use can be decreased, or hydrocortisone can be discontinued and restarted again with any recurrence of discomfort. Many clinicians also prescribe weekly fluconazole to prevent intercurrent candidiasis.

Related article: Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis. Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, July 2013)

CASE 5. PLAQUES ON VULVA AND IN SKIN FOLDS

A 43-year-old woman reports a recalcitrant yeast infection of the vulva, with itching and irritation. She is overweight and diabetic, with mild stress incontinence.

Physical examination reveals a fairly well-demarcated plaque of redness of the vulva and labiocrural folds, with satellite red papules and peripheral peeling (FIGURE 5). An examination of other skin surfaces reveals similar plaques in the gluteal cleft, umbilicus, and axillae as well as under the breasts. A fungal preparation of the vagina and skin is negative. You obtain a fungal culture and prescribe topical and oral antifungal therapy and see the patient again 1 week later. Her condition is unchanged.

Diagnosis: You make a presumptive diagnosis of inverse psoriasis and do a confirmatory punch biopsy.

Treatment: Clobetasol ointment applied to the skin folds, along with continuation of the topical miconazole cream. A week later, the patient’s condition is remarkably improved, and her biopsy shows psoriasiform dermatitis. You reduce the potency of her corticosteroid, switching to desonide cream sparingly applied daily.

Psoriasis is a common skin disease of immunologic origin. The skin is classically red and thick, with heavy white scale produced by rapid turnover of epithelium. However, there are several morphologic types of psoriasis, and anogenital psoriasis is most often of the inverse pattern. Inverse psoriasis preferentially affects skin folds and is frequently mistaken for (and often initially superinfected with) candidiasis. Scale is thin and unapparent, and there often is a shiny, glazed appearance to the skin. Tiny satellite lesions often are visible as well. A skin biopsy of inverse psoriasis often is not diagnostic, showing only nonspecific psoriasiform dermatitis; this does not disprove psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a systemic condition and is associated with metabolic syndrome, carrying an increased risk of overweight, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Management of these conditions is very important in the treatment of the patient overall.

Unlike lichen planus and lichen sclerosus, scarring is rare with psoriasis, and squamous cell carcinoma generally is unassociated.7,8

Anogenital psoriasis is treated with topical corticosteroids and, when needed, topical vitamin D preparations. Generally, inverse psoriasis is controlled with low-potency topical corticosteroids, with management of secondary infection and irritants. Otherwise, ultraviolet light is a time-honored therapy for psoriasis but not practical for skin folds. It also is difficult for many patients to manage with a busy life. Systemic therapy, including methotrexate and oral retinoids are often used, as are newer biologic agents such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article or on any topic relevant to ObGyns and women’s health practitioners. Tell us which topics you’d like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. We will consider publishing your letter and in a future issue. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice. Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman ML. Resistance and barriers to local estrogen therapy in women with atrophic vaginitis.

J Sex Med. 2013;10(6):1567–1574. - Huppert JS, Gerber MA, Deitch HR, et al. Vulvar ulcers in young females: A manifestation of aphthosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19(3):195–204.

- O’Neill ID. Efficacy of tumour necrosis factor-a antagonists in aphthous ulceration: Review of published individual patient data. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(2):231–235.

- Sanchez-Cano D, Callejas-Rubio JL, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Ortego-Centeno N. Recalcitrant, recurrent aphthous stomatitis successfully treated with adalimumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(2):206.

- Stockdale CK. Clinical spectrum of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(6):479–483.

- Sobel JD, Reichman O, Misra D, Yoo W. Prognosis and treatment of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):850–855.

- Albert S, Neill S, Derrick EK, Calonje E. Psoriasis associated with vulvar scarring. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(4):354–356.

- Boffetta P, Gridley G, Lindelöf B. Cancer risk in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized for psoriasis in Sweden. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(6):1531–1537.

Chronic irritation, itching, and pain are only rarely due to infection. These symptoms are more likely to be caused by dermatoses, vaginal abnormalities, and pain syndromes that may be difficult to diagnose. Careful evaluation should include a wet mount and culture to eliminate infection as a cause so that the correct diagnosis can be ascertained and treated.

In Part 2 of this two-part series, we focus on five cases of vulvar dermatologic disruptions:

- atrophic vagina

- irritant and allergic contact dermatitis

- complex vulvar aphthosis

- desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

- inverse psoriasis.

CASE 1. INTROITAL BURNING AND A FEAR OF BREAST CANCER

A 56-year-old woman visits your office for management of recent-onset introital burning during sexual activity. She reports that her commercial lubricant causes irritation. Topical and oral antifungal therapies have not been beneficial. She has a strong family history of breast cancer.

On examination, she exhibits small, smooth labia minora and experiences pain when a cotton swab is pressed against the vestibule. The vagina is also smooth, with scant secretions. Microscopically, these secretions are almost acellular, with no increase in white blood cells and no clue cells, yeast forms, or lactobacilli. The pH is greater than 6.5, and most epithelial cells are parabasal (FIGURE 1).

You prescribe topical estradiol cream for vaginal use three nights per week, but when the patient returns 1 month later, her condition is unchanged. She explains that she never used the cream after reading the package insert, which reports a risk of breast cancer.

Diagnosis: Atrophic vagina (not atrophic vaginitis, as there is no increase in white blood cells).

Treatment: Re-estrogenization should relieve her symptoms.

Several options for local estrogen replacement are available. Creams include estradiol (Estrace) and conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin), the latter of which is arguably slightly more irritating. These are prescribed at a starting dose of 1 g in the vagina three nights per week. After several weeks, they can be titrated to the lowest frequency that controls symptoms.

The risk of vaginal candidiasis is fairly high during the first 2 or 3 weeks of re-estrogenization, so patients should be warned of this possibility. Also consider prophylactic weekly fluconazole or an azole suppository two or three times a week for the first few weeks. Estradiol tablets (Vagifem) inserted in the vagina are effective, less messy, and more expensive, as is the estradiol ring (Estring), which is inserted and changed quarterly.

It is not unusual for a woman to avoid use of topical estrogen out of fear, or to use insufficient amounts only on the vulva, or to use it for only 1 or 2 weeks.1

Women should be scheduled for a return visit to ensure they have been using the estrogen, their wet mount has normalized, and discomfort has cleared.

Related article: Your menopausal patient's breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia. JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD (Cases in Menopause; May 2013)

When a woman is reluctant to use local estrogen

We counsel women that small doses of vaginal estrogen used for limited periods of time are unlikely to influence their breast cancer risk and are the most effective treatment for symptoms of atrophy. Usually, this explanation is sufficient to reassure a woman that topical estrogen is safe. Otherwise, use of commercial personal lubricants (silicone-based lubricants are well tolerated) and moisturizers such as Replens and RePhresh can be comforting.

The topical anesthetics lidocaine 2% jelly or lidocaine 5% ointment (which sometimes burns) can minimize pain with sexual activity for those requiring more than lubrication.

Ospemifene (Osphena) is used by some clinicians in this situation, but this medication is labeled as a risk for all of the same contraindications as systemic estrogen, and it is much more expensive than topical estrogen. Ospemifene is an estrogen agonist/antagonist. Although it is the only oral medication indicated for the treatment of menopause-related dyspareunia, the long-term effects on breast cancer risk are unknown. Also, it has an agonist effect on the endometrium and, again, the long-term risk is unknown.

Related article: New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (News for your Practice; May 2013)

Fluconazole use is contraindicated with ospemifene, as is the use of any estrogen products.

CASE 2. RECALCITRANT ITCHING, BURNING, AND REDNESS

A 25-year-old woman reports anogenital itching, burning, and redness, which have been present for 3 months. She says she developed a yeast infection after antibiotic therapy for a dental infection; the yeast infection was treated with terconazole. She reports an allergic reaction to the terconazole, with immediate severe burning, redness, and swelling. The clobetasol cream she was given to use twice daily also caused burning, so she discontinued it. Her symptoms improved when she tried cool soaks and applied topical benzocaine gel as a local anesthetic. However,

2 weeks later, she experienced increasing redness, itching, and burning. Although the benzocaine relieved these symptoms, it required almost continual reapplication for comfort.

A physical examination of the vulva reveals generalized, poorly demarcated redness, edema, and superficial erosions (FIGURE 2).

Diagnosis: Irritant contact dermatitis (as opposed to allergic contact dermatitis) associated with the use of terconazole and clobetasol. This was followed by allergic contact dermatitis in association with benzocaine.

Treatment: Withdrawal of benzocaine, with reinitiation of cool soaks and a switch to clobetasol ointment rather than cream. Nighttime sedation allows the patient to sleep through the itching and gradually allows her skin to heal.

Contact dermatitis is a fairly common cause of vulvar irritation, with two main types:

- Irritant contact dermatitis—The most common form, it occurs in any individual exposed to an irritating substance in sufficient quantity or frequency. Irritant contact dermatitis is characterized mostly by sensations of rawness or burning and generally is caused by urine, feces, perspiration, friction, alcohols in topical creams, overwashing, and use of harsh soaps.

- Allergic contact dermatitis—This form is characterized by itching, although secondary pain and burning from scratching and blistering can occur as well. Common allergens in the genital area include benzocaine, diphenhydramine (Benadryl), neomycin in triple antibiotic ointment (Neosporin), and latex. Allergic contact dermatitis occurs after 1 or 2 weeks of initial exposure or 1 or 2 days after re-exposure.

The diagnosis of an irritant or allergic contact dermatitis can be based on a history of incontinence, application of high-risk substances, or inappropriate washing. Management generally involves discontinuation of all panty liners and topical agents except for water, with a topical steroid ointment used twice a day and pure petroleum jelly used as often as necessary for comfort. Nighttime sedation to allow a reprieve from rubbing and scratching may be helpful, and narcotic pain medications may be useful for the first 1 to 2 weeks of treatment.

Women who fail to respond to treatment should be referred for patch testing by a

dermatologist.

Related article: Vulvar pain syndromes: Making the correct diagnosis. Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH; Libby Edwards, MD; Jennifer Gunter, MD; Hope K. Haefner, MD (Roundtable, part 1 of 3; September 2011)

CASE 3. TEENAGER WITH VULVAR PAIN AND SORES

A woman brings her 13-year-old daughter to your office for treatment of sudden-onset vulvar pain and sores. The child developed a sore throat and low-grade fever 3 days earlier, with vulvar pain and vulvar dysuria the next day. The pediatrician diagnosed a herpes simplex virus infection and prescribed oral acyclovir, but the girl’s condition has not improved, and the mother believes her daughter’s claims of sexual abstinence.

The girl is otherwise healthy, aside from a history of trivial oral canker sores without arthritis, headaches, abdominal pain, eye pain, or vision changes.

Physical examination of the vulva reveals soft, painful, well-demarcated ulcers with a white fibrin base (FIGURE 3).

Diagnosis: Complex aphthosis. Further testing is unnecessary.

Treatment: Prednisone 40 mg/day plus hydrocodone in usual doses of 5/325, one or two tablets every 4 to 6 hours, as needed; topical petroleum jelly (especially before urination); and sitz baths. When the patient returns 1 week later, she is much improved.

Aphthae are believed to be of hyperimmune origin, often precipitated by a viral syndrome. They are most common in girls aged 9 to 18 years. Vulvar aphthae are triggered by various viral infections, including Epstein-Barr.2 The offending virus is not located in the ulcer proper, however, but is identified serologically.

Aphthae are uncommon and under-recognized on the vulva, and genital aphthae are usually much larger than oral aphthae. Most patients initially are mistakenly evaluated and treated for sexually transmitted disease, but the large, well-demarcated, painful, nonindurated deep nature of the ulcer is pathognomonic for an aphthous ulcer.

The presence of oral and genital aphthae does not constitute a diagnosis of Behçet disease, an often-devastating systemic inflammatory condition occurring almost exclusively in men in the Middle and Far East. The diagnosis of Behçet disease requires the identification of objective inflammatory disease of the eyes, joints, gastrointestinal tract, or neurologic system. True Behçet disease is incredibly uncommon in the United States. When it is diagnosed in Western countries, it takes an attenuated form, most often occurring in women who experience multisystem discomfort rather than identifiable inflammatory disease. End-organ damage is uncommon. Evaluation for Behçet disease in women with vulvar aphthae generally is not indicated, although a directed review of systems is reasonable. The rare patient who experiences frequent recurrence and symptoms of systemic disease should be referred to an ophthalmologist and other relevant specialists to evaluate for inflammatory disease.

The treatment of vulvar aphthae consists of systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone 40 mg/day for smaller individuals and 60 mg/day for larger women, with follow-up to ensure a good response. Often, the prednisone can be discontinued when pain relents rather than continued through complete healing. Reassurance, without discussing Behçet disease, is paramount, as is pain control. The heavy application of petroleum jelly can decrease pain and prevent urine from touching the ulcer.

Some patients experience recurrent ulcers. A second prescription of prednisone can be provided for immediate reinstitution with onset of symptoms. However, frequent recurrences may require ongoing suppressive medication, with dapsone being the usual first choice. Colchicine often is used, and thalidomide and tumor necrosis factor-a blockers (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) also are extremely beneficial.3,4

CASE 4. INCREASED NEUTROPHILS AND NO LACTOBACILLI

A 36-year-old woman visits your office reporting introital itching, vulvar dysuria, and superficial dyspareunia that have lasted 6 months. She has tried over-the-counter antifungal therapy, with only slight improvement while using the cream. Her health is normal otherwise, lacking pain syndromes or abnormalities suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction. She experienced comfortable sexual activity until 6 months ago.

The only abnormalities apparent on physical examination are redness of the vestibule, medial labia minora, and vaginal walls, with edema of the surrounding skin and no oral lesions (FIGURE 4A). Copious vaginal secretions are visible at the introitus. A wet mount shows a marked increase in neutrophils with scattered parabasal cells (FIGURE 4B). There are no clue cells, lactobacilli, or yeast forms. The patient’s pH level is greater than 6.5. Routine and fungal cultures and molecular studies for chlamydia, trichomonas, and gonorrhea are returned as normal.

Diagnosis: Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

Treatment: Clindamycin vaginal cream, 1/2 to 1 full applicator nightly, with a weekly oral fluconazole tablet (200 mg is more easily covered by insurance) to prevent secondary candidiasis. You schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) is described as noninfectious inflammatory vaginitis in a setting of normal estrogen and absence of skin disease of the mucous membranes of the vagina. The condition is characterized by an increase in white blood cells and parabasal cells, and absent lactobacilli, with relatively high vaginal pH. DIV is thought to represent an inflammatory dermatosis of the vaginal epithelium.5 Although some clinicians believe that DIV is actually lichen planus, the latter exhibits erosions as well as redness, nearly always affects the mouth and the vulva, and produces remarkable scarring. DIV does not erode, affect any other skin surfaces, or scar.

Other rare skin diseases that produce erosions and scarring also can be ruled out by the presence of erosions, absence of oral disease, and absence of other mucosal involvement. These diseases include cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Infectious diseases characterized by inflammation are excluded by culture or molecular studies, and atrophic vaginitis and retained foreign bodies (especially retained tampons) can produce a similar picture.

The vulvar itching and irritation that occur with DIV most likely represent an irritant contact dermatitis, with vaginal secretions serving as the irritant.

How to treat DIV

The management of DIV consists of either topical clindamycin cream (theoretically for its anti-inflammatory rather than antimicrobial properties) or intravaginal corticosteroids, especially hydrocortisone acetate.6 Hydrocortisone can be tried at the low commercially available dose of 25-mg rectal suppositories, which should be inserted into the vagina nightly, or it can be compounded at 100 or 200 mg, if needed. If the condition is recalcitrant, combination therapy can be used.

When signs and symptoms abate, the frequency of use can be decreased, or hydrocortisone can be discontinued and restarted again with any recurrence of discomfort. Many clinicians also prescribe weekly fluconazole to prevent intercurrent candidiasis.

Related article: Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis. Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, July 2013)

CASE 5. PLAQUES ON VULVA AND IN SKIN FOLDS

A 43-year-old woman reports a recalcitrant yeast infection of the vulva, with itching and irritation. She is overweight and diabetic, with mild stress incontinence.

Physical examination reveals a fairly well-demarcated plaque of redness of the vulva and labiocrural folds, with satellite red papules and peripheral peeling (FIGURE 5). An examination of other skin surfaces reveals similar plaques in the gluteal cleft, umbilicus, and axillae as well as under the breasts. A fungal preparation of the vagina and skin is negative. You obtain a fungal culture and prescribe topical and oral antifungal therapy and see the patient again 1 week later. Her condition is unchanged.

Diagnosis: You make a presumptive diagnosis of inverse psoriasis and do a confirmatory punch biopsy.

Treatment: Clobetasol ointment applied to the skin folds, along with continuation of the topical miconazole cream. A week later, the patient’s condition is remarkably improved, and her biopsy shows psoriasiform dermatitis. You reduce the potency of her corticosteroid, switching to desonide cream sparingly applied daily.

Psoriasis is a common skin disease of immunologic origin. The skin is classically red and thick, with heavy white scale produced by rapid turnover of epithelium. However, there are several morphologic types of psoriasis, and anogenital psoriasis is most often of the inverse pattern. Inverse psoriasis preferentially affects skin folds and is frequently mistaken for (and often initially superinfected with) candidiasis. Scale is thin and unapparent, and there often is a shiny, glazed appearance to the skin. Tiny satellite lesions often are visible as well. A skin biopsy of inverse psoriasis often is not diagnostic, showing only nonspecific psoriasiform dermatitis; this does not disprove psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a systemic condition and is associated with metabolic syndrome, carrying an increased risk of overweight, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Management of these conditions is very important in the treatment of the patient overall.

Unlike lichen planus and lichen sclerosus, scarring is rare with psoriasis, and squamous cell carcinoma generally is unassociated.7,8

Anogenital psoriasis is treated with topical corticosteroids and, when needed, topical vitamin D preparations. Generally, inverse psoriasis is controlled with low-potency topical corticosteroids, with management of secondary infection and irritants. Otherwise, ultraviolet light is a time-honored therapy for psoriasis but not practical for skin folds. It also is difficult for many patients to manage with a busy life. Systemic therapy, including methotrexate and oral retinoids are often used, as are newer biologic agents such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article or on any topic relevant to ObGyns and women’s health practitioners. Tell us which topics you’d like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. We will consider publishing your letter and in a future issue. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice. Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

Chronic irritation, itching, and pain are only rarely due to infection. These symptoms are more likely to be caused by dermatoses, vaginal abnormalities, and pain syndromes that may be difficult to diagnose. Careful evaluation should include a wet mount and culture to eliminate infection as a cause so that the correct diagnosis can be ascertained and treated.

In Part 2 of this two-part series, we focus on five cases of vulvar dermatologic disruptions:

- atrophic vagina

- irritant and allergic contact dermatitis

- complex vulvar aphthosis

- desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

- inverse psoriasis.

CASE 1. INTROITAL BURNING AND A FEAR OF BREAST CANCER

A 56-year-old woman visits your office for management of recent-onset introital burning during sexual activity. She reports that her commercial lubricant causes irritation. Topical and oral antifungal therapies have not been beneficial. She has a strong family history of breast cancer.

On examination, she exhibits small, smooth labia minora and experiences pain when a cotton swab is pressed against the vestibule. The vagina is also smooth, with scant secretions. Microscopically, these secretions are almost acellular, with no increase in white blood cells and no clue cells, yeast forms, or lactobacilli. The pH is greater than 6.5, and most epithelial cells are parabasal (FIGURE 1).

You prescribe topical estradiol cream for vaginal use three nights per week, but when the patient returns 1 month later, her condition is unchanged. She explains that she never used the cream after reading the package insert, which reports a risk of breast cancer.

Diagnosis: Atrophic vagina (not atrophic vaginitis, as there is no increase in white blood cells).

Treatment: Re-estrogenization should relieve her symptoms.

Several options for local estrogen replacement are available. Creams include estradiol (Estrace) and conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin), the latter of which is arguably slightly more irritating. These are prescribed at a starting dose of 1 g in the vagina three nights per week. After several weeks, they can be titrated to the lowest frequency that controls symptoms.

The risk of vaginal candidiasis is fairly high during the first 2 or 3 weeks of re-estrogenization, so patients should be warned of this possibility. Also consider prophylactic weekly fluconazole or an azole suppository two or three times a week for the first few weeks. Estradiol tablets (Vagifem) inserted in the vagina are effective, less messy, and more expensive, as is the estradiol ring (Estring), which is inserted and changed quarterly.

It is not unusual for a woman to avoid use of topical estrogen out of fear, or to use insufficient amounts only on the vulva, or to use it for only 1 or 2 weeks.1

Women should be scheduled for a return visit to ensure they have been using the estrogen, their wet mount has normalized, and discomfort has cleared.

Related article: Your menopausal patient's breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia. JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD (Cases in Menopause; May 2013)

When a woman is reluctant to use local estrogen

We counsel women that small doses of vaginal estrogen used for limited periods of time are unlikely to influence their breast cancer risk and are the most effective treatment for symptoms of atrophy. Usually, this explanation is sufficient to reassure a woman that topical estrogen is safe. Otherwise, use of commercial personal lubricants (silicone-based lubricants are well tolerated) and moisturizers such as Replens and RePhresh can be comforting.

The topical anesthetics lidocaine 2% jelly or lidocaine 5% ointment (which sometimes burns) can minimize pain with sexual activity for those requiring more than lubrication.

Ospemifene (Osphena) is used by some clinicians in this situation, but this medication is labeled as a risk for all of the same contraindications as systemic estrogen, and it is much more expensive than topical estrogen. Ospemifene is an estrogen agonist/antagonist. Although it is the only oral medication indicated for the treatment of menopause-related dyspareunia, the long-term effects on breast cancer risk are unknown. Also, it has an agonist effect on the endometrium and, again, the long-term risk is unknown.

Related article: New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (News for your Practice; May 2013)

Fluconazole use is contraindicated with ospemifene, as is the use of any estrogen products.

CASE 2. RECALCITRANT ITCHING, BURNING, AND REDNESS

A 25-year-old woman reports anogenital itching, burning, and redness, which have been present for 3 months. She says she developed a yeast infection after antibiotic therapy for a dental infection; the yeast infection was treated with terconazole. She reports an allergic reaction to the terconazole, with immediate severe burning, redness, and swelling. The clobetasol cream she was given to use twice daily also caused burning, so she discontinued it. Her symptoms improved when she tried cool soaks and applied topical benzocaine gel as a local anesthetic. However,

2 weeks later, she experienced increasing redness, itching, and burning. Although the benzocaine relieved these symptoms, it required almost continual reapplication for comfort.

A physical examination of the vulva reveals generalized, poorly demarcated redness, edema, and superficial erosions (FIGURE 2).

Diagnosis: Irritant contact dermatitis (as opposed to allergic contact dermatitis) associated with the use of terconazole and clobetasol. This was followed by allergic contact dermatitis in association with benzocaine.

Treatment: Withdrawal of benzocaine, with reinitiation of cool soaks and a switch to clobetasol ointment rather than cream. Nighttime sedation allows the patient to sleep through the itching and gradually allows her skin to heal.

Contact dermatitis is a fairly common cause of vulvar irritation, with two main types:

- Irritant contact dermatitis—The most common form, it occurs in any individual exposed to an irritating substance in sufficient quantity or frequency. Irritant contact dermatitis is characterized mostly by sensations of rawness or burning and generally is caused by urine, feces, perspiration, friction, alcohols in topical creams, overwashing, and use of harsh soaps.

- Allergic contact dermatitis—This form is characterized by itching, although secondary pain and burning from scratching and blistering can occur as well. Common allergens in the genital area include benzocaine, diphenhydramine (Benadryl), neomycin in triple antibiotic ointment (Neosporin), and latex. Allergic contact dermatitis occurs after 1 or 2 weeks of initial exposure or 1 or 2 days after re-exposure.

The diagnosis of an irritant or allergic contact dermatitis can be based on a history of incontinence, application of high-risk substances, or inappropriate washing. Management generally involves discontinuation of all panty liners and topical agents except for water, with a topical steroid ointment used twice a day and pure petroleum jelly used as often as necessary for comfort. Nighttime sedation to allow a reprieve from rubbing and scratching may be helpful, and narcotic pain medications may be useful for the first 1 to 2 weeks of treatment.

Women who fail to respond to treatment should be referred for patch testing by a

dermatologist.

Related article: Vulvar pain syndromes: Making the correct diagnosis. Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH; Libby Edwards, MD; Jennifer Gunter, MD; Hope K. Haefner, MD (Roundtable, part 1 of 3; September 2011)

CASE 3. TEENAGER WITH VULVAR PAIN AND SORES

A woman brings her 13-year-old daughter to your office for treatment of sudden-onset vulvar pain and sores. The child developed a sore throat and low-grade fever 3 days earlier, with vulvar pain and vulvar dysuria the next day. The pediatrician diagnosed a herpes simplex virus infection and prescribed oral acyclovir, but the girl’s condition has not improved, and the mother believes her daughter’s claims of sexual abstinence.

The girl is otherwise healthy, aside from a history of trivial oral canker sores without arthritis, headaches, abdominal pain, eye pain, or vision changes.

Physical examination of the vulva reveals soft, painful, well-demarcated ulcers with a white fibrin base (FIGURE 3).

Diagnosis: Complex aphthosis. Further testing is unnecessary.

Treatment: Prednisone 40 mg/day plus hydrocodone in usual doses of 5/325, one or two tablets every 4 to 6 hours, as needed; topical petroleum jelly (especially before urination); and sitz baths. When the patient returns 1 week later, she is much improved.

Aphthae are believed to be of hyperimmune origin, often precipitated by a viral syndrome. They are most common in girls aged 9 to 18 years. Vulvar aphthae are triggered by various viral infections, including Epstein-Barr.2 The offending virus is not located in the ulcer proper, however, but is identified serologically.

Aphthae are uncommon and under-recognized on the vulva, and genital aphthae are usually much larger than oral aphthae. Most patients initially are mistakenly evaluated and treated for sexually transmitted disease, but the large, well-demarcated, painful, nonindurated deep nature of the ulcer is pathognomonic for an aphthous ulcer.

The presence of oral and genital aphthae does not constitute a diagnosis of Behçet disease, an often-devastating systemic inflammatory condition occurring almost exclusively in men in the Middle and Far East. The diagnosis of Behçet disease requires the identification of objective inflammatory disease of the eyes, joints, gastrointestinal tract, or neurologic system. True Behçet disease is incredibly uncommon in the United States. When it is diagnosed in Western countries, it takes an attenuated form, most often occurring in women who experience multisystem discomfort rather than identifiable inflammatory disease. End-organ damage is uncommon. Evaluation for Behçet disease in women with vulvar aphthae generally is not indicated, although a directed review of systems is reasonable. The rare patient who experiences frequent recurrence and symptoms of systemic disease should be referred to an ophthalmologist and other relevant specialists to evaluate for inflammatory disease.

The treatment of vulvar aphthae consists of systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone 40 mg/day for smaller individuals and 60 mg/day for larger women, with follow-up to ensure a good response. Often, the prednisone can be discontinued when pain relents rather than continued through complete healing. Reassurance, without discussing Behçet disease, is paramount, as is pain control. The heavy application of petroleum jelly can decrease pain and prevent urine from touching the ulcer.

Some patients experience recurrent ulcers. A second prescription of prednisone can be provided for immediate reinstitution with onset of symptoms. However, frequent recurrences may require ongoing suppressive medication, with dapsone being the usual first choice. Colchicine often is used, and thalidomide and tumor necrosis factor-a blockers (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) also are extremely beneficial.3,4

CASE 4. INCREASED NEUTROPHILS AND NO LACTOBACILLI

A 36-year-old woman visits your office reporting introital itching, vulvar dysuria, and superficial dyspareunia that have lasted 6 months. She has tried over-the-counter antifungal therapy, with only slight improvement while using the cream. Her health is normal otherwise, lacking pain syndromes or abnormalities suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction. She experienced comfortable sexual activity until 6 months ago.

The only abnormalities apparent on physical examination are redness of the vestibule, medial labia minora, and vaginal walls, with edema of the surrounding skin and no oral lesions (FIGURE 4A). Copious vaginal secretions are visible at the introitus. A wet mount shows a marked increase in neutrophils with scattered parabasal cells (FIGURE 4B). There are no clue cells, lactobacilli, or yeast forms. The patient’s pH level is greater than 6.5. Routine and fungal cultures and molecular studies for chlamydia, trichomonas, and gonorrhea are returned as normal.

Diagnosis: Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

Treatment: Clindamycin vaginal cream, 1/2 to 1 full applicator nightly, with a weekly oral fluconazole tablet (200 mg is more easily covered by insurance) to prevent secondary candidiasis. You schedule a follow-up visit in 1 month.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) is described as noninfectious inflammatory vaginitis in a setting of normal estrogen and absence of skin disease of the mucous membranes of the vagina. The condition is characterized by an increase in white blood cells and parabasal cells, and absent lactobacilli, with relatively high vaginal pH. DIV is thought to represent an inflammatory dermatosis of the vaginal epithelium.5 Although some clinicians believe that DIV is actually lichen planus, the latter exhibits erosions as well as redness, nearly always affects the mouth and the vulva, and produces remarkable scarring. DIV does not erode, affect any other skin surfaces, or scar.

Other rare skin diseases that produce erosions and scarring also can be ruled out by the presence of erosions, absence of oral disease, and absence of other mucosal involvement. These diseases include cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Infectious diseases characterized by inflammation are excluded by culture or molecular studies, and atrophic vaginitis and retained foreign bodies (especially retained tampons) can produce a similar picture.

The vulvar itching and irritation that occur with DIV most likely represent an irritant contact dermatitis, with vaginal secretions serving as the irritant.

How to treat DIV

The management of DIV consists of either topical clindamycin cream (theoretically for its anti-inflammatory rather than antimicrobial properties) or intravaginal corticosteroids, especially hydrocortisone acetate.6 Hydrocortisone can be tried at the low commercially available dose of 25-mg rectal suppositories, which should be inserted into the vagina nightly, or it can be compounded at 100 or 200 mg, if needed. If the condition is recalcitrant, combination therapy can be used.

When signs and symptoms abate, the frequency of use can be decreased, or hydrocortisone can be discontinued and restarted again with any recurrence of discomfort. Many clinicians also prescribe weekly fluconazole to prevent intercurrent candidiasis.

Related article: Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis. Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, July 2013)

CASE 5. PLAQUES ON VULVA AND IN SKIN FOLDS

A 43-year-old woman reports a recalcitrant yeast infection of the vulva, with itching and irritation. She is overweight and diabetic, with mild stress incontinence.

Physical examination reveals a fairly well-demarcated plaque of redness of the vulva and labiocrural folds, with satellite red papules and peripheral peeling (FIGURE 5). An examination of other skin surfaces reveals similar plaques in the gluteal cleft, umbilicus, and axillae as well as under the breasts. A fungal preparation of the vagina and skin is negative. You obtain a fungal culture and prescribe topical and oral antifungal therapy and see the patient again 1 week later. Her condition is unchanged.

Diagnosis: You make a presumptive diagnosis of inverse psoriasis and do a confirmatory punch biopsy.

Treatment: Clobetasol ointment applied to the skin folds, along with continuation of the topical miconazole cream. A week later, the patient’s condition is remarkably improved, and her biopsy shows psoriasiform dermatitis. You reduce the potency of her corticosteroid, switching to desonide cream sparingly applied daily.

Psoriasis is a common skin disease of immunologic origin. The skin is classically red and thick, with heavy white scale produced by rapid turnover of epithelium. However, there are several morphologic types of psoriasis, and anogenital psoriasis is most often of the inverse pattern. Inverse psoriasis preferentially affects skin folds and is frequently mistaken for (and often initially superinfected with) candidiasis. Scale is thin and unapparent, and there often is a shiny, glazed appearance to the skin. Tiny satellite lesions often are visible as well. A skin biopsy of inverse psoriasis often is not diagnostic, showing only nonspecific psoriasiform dermatitis; this does not disprove psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a systemic condition and is associated with metabolic syndrome, carrying an increased risk of overweight, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Management of these conditions is very important in the treatment of the patient overall.

Unlike lichen planus and lichen sclerosus, scarring is rare with psoriasis, and squamous cell carcinoma generally is unassociated.7,8

Anogenital psoriasis is treated with topical corticosteroids and, when needed, topical vitamin D preparations. Generally, inverse psoriasis is controlled with low-potency topical corticosteroids, with management of secondary infection and irritants. Otherwise, ultraviolet light is a time-honored therapy for psoriasis but not practical for skin folds. It also is difficult for many patients to manage with a busy life. Systemic therapy, including methotrexate and oral retinoids are often used, as are newer biologic agents such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article or on any topic relevant to ObGyns and women’s health practitioners. Tell us which topics you’d like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. We will consider publishing your letter and in a future issue. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice. Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman ML. Resistance and barriers to local estrogen therapy in women with atrophic vaginitis.

J Sex Med. 2013;10(6):1567–1574. - Huppert JS, Gerber MA, Deitch HR, et al. Vulvar ulcers in young females: A manifestation of aphthosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19(3):195–204.

- O’Neill ID. Efficacy of tumour necrosis factor-a antagonists in aphthous ulceration: Review of published individual patient data. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(2):231–235.

- Sanchez-Cano D, Callejas-Rubio JL, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Ortego-Centeno N. Recalcitrant, recurrent aphthous stomatitis successfully treated with adalimumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(2):206.

- Stockdale CK. Clinical spectrum of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(6):479–483.

- Sobel JD, Reichman O, Misra D, Yoo W. Prognosis and treatment of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):850–855.

- Albert S, Neill S, Derrick EK, Calonje E. Psoriasis associated with vulvar scarring. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(4):354–356.

- Boffetta P, Gridley G, Lindelöf B. Cancer risk in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized for psoriasis in Sweden. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(6):1531–1537.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman ML. Resistance and barriers to local estrogen therapy in women with atrophic vaginitis.

J Sex Med. 2013;10(6):1567–1574. - Huppert JS, Gerber MA, Deitch HR, et al. Vulvar ulcers in young females: A manifestation of aphthosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19(3):195–204.

- O’Neill ID. Efficacy of tumour necrosis factor-a antagonists in aphthous ulceration: Review of published individual patient data. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(2):231–235.

- Sanchez-Cano D, Callejas-Rubio JL, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Ortego-Centeno N. Recalcitrant, recurrent aphthous stomatitis successfully treated with adalimumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(2):206.

- Stockdale CK. Clinical spectrum of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(6):479–483.

- Sobel JD, Reichman O, Misra D, Yoo W. Prognosis and treatment of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):850–855.

- Albert S, Neill S, Derrick EK, Calonje E. Psoriasis associated with vulvar scarring. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(4):354–356.

- Boffetta P, Gridley G, Lindelöf B. Cancer risk in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized for psoriasis in Sweden. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(6):1531–1537.

Read Part 1: Chronic vulvar symptoms and dermatologic disruptions: How to make the correct diagnosis (May 2014)

Chronic vulvar symptoms and dermatologic disruptions: How to make the correct diagnosis

Nearly one in every six women will experience chronic vulvar symptoms at some point, from ongoing itching to sensations of rawness, burning, or dyspareunia. Regrettably, clinicians generally are taught only a few possible causes for these symptoms, primarily infections such as yeast, bacterial vaginosis, herpes simplex virus, or anogenital warts. However, infections rarely produce chronic symptoms that do not respond, at least temporarily, to therapy.

In this two-part series, we focus on a total of 10 cases of vulvar symptoms, zeroing in on diagnosis and treatment. In this first part, we describe five patient scenarios illustrating the diagnosis and treatment of:

- lichen sclerosus

- vulvodynia

- lichen simplex chronicus

- lichen planus

- hidradenitis suppurativa.

In many chronic cases, more than one entity is the cause

Specific skin diseases, sensations of rawness from various external and internal irritants, neuropathy, and psychological issues are all much more common causes of chronic vulvar symptoms than infection. Moreover, most women with chronic vulvar symptoms have more than one entity producing their discomfort.

Very often, the cause of a patient’s symptoms is not clear at the first visit, with nonspecific redness or even normal skin seen on examination. Pathognomonic skin findings can be obscured by irritant contact dermatitis caused by unnecessary medications or overwashing, atrophic vaginitis, and/or rubbing and scratching. In such cases, obvious abnormalities must be eliminated and the patient reevaluated to definitively discover and treat the cause of the symptoms.

CASE 1. ANOGENITAL ITCHING AND DYSPAREUNIA

A 62-year-old woman schedules a visit to address her anogenital itching. She reports pain with scratching and has developed introital dyspareunia. On physical examination, you find a well-demarcated white plaque of thickened, crinkled skin (FIGURE 1). A wet mount shows parabasal cells and no lactobacilli.

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus and atrophic vagina.

Treatment: Halobetasol ointment, an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid, once or twice daily; along with estradiol cream (0.5 g intravaginally) 3 times a week.

Lichen sclerosus is a skin disease found most often on the vulva of postmenopausal women, although it also can affect prepubertal children and reproductive-age women. Lichen sclerosus is multifactorial in pathogenesis, including prominent autoimmune factors, local environmental factors, and genetic predisposition.1

Although there is no cure for lichen sclerosus, the symptoms and clinical abnormalities usually can be well managed with ultra-potent topical corticosteroids. However, scarring and architectural changes are not reversible. Moreover, poorly controlled lichen sclerosus exhibits malignant transformation on anogenital skin in about 3% of affected patients.

The standard of care is application of an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid ointment once or twice daily until the skin texture normalizes again. The most common of such corticosteroids are clobetasol, halobetasol, and betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle (betamethasone dipropionate in the usual vehicle is only a medium-high medication in terms of potency.) One of us (L.E.) finds that some women experience irritation with generic clobetasol.

The ointment form of the selected corticosteroid is preferred, as creams are irritating to the vulva in most women because they contain more alcohols and preservatives than ointments do. The amount to be used is very small—far smaller than the pea-sized amount often suggested. By using this smaller amount, we avoid spread to the surrounding hair-bearing skin, which is at greater risk for steroid dermatitis and atrophy than the modified mucous membranes.

Related video: Lichen sclerosis: My approach to treatment Michael Baggish, MD

Even asymptomatic lichen sclerosus can progress

Most vulvologists agree that when the skin normalizes (not when symptoms subside), it is best to either decrease the frequency of application of the ultra-potent corticosteroid to two or three times a week, or to continue daily use with a lower-potency corticosteroid such as triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. Discontinuation of therapy usually results in recurrence.2

Treatment should not be based solely on symptoms, as asymptomatic lichen sclerosus can progress and cause permanent scarring and an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.

Although no studies have shown a decreased risk for squamous cell carcinoma with ongoing use of a corticosteroid, vulvologists have observed that malignant transformation occurs uniformly in the setting of poorly controlled lichen sclerosus. Immune dysregulation and inflammation may play an important role, so careful management to minimize inflammation may help prevent a malignancy.3

Secondary treatment choices

Secondary choices for lichen sclerosus include the topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel) but not testosterone, which has been shown to be ineffective. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are useful but often burn upon application, and they are “black-boxed” for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma. Therefore, although squamous cell carcinoma associated with their use is extraordinarily uncommon, patients should be advised of these risks, particularly because lichen sclerosus already exhibits this association.

Most postmenopausal women with lichen sclerosus also exhibit hypothyroidism, so they should be monitored for this. However, thyroid function testing in 18 children showed no evidence of hypothyroidism in that age group (L.E. unpublished data).

Estrogen replacement may be advised

Postmenopausal women who have prominent introital lichen sclerosus or dyspareunia should receive estrogen replacement of some type so that there is only one cause, rather than two, for their dyspareunia, thinning, fragility, and inelasticity.

Women with well-controlled lichen sclerosus should be followed twice a year to ensure that their disease remains suppressed with ongoing therapy, and to evaluate for active disease, adverse effects of therapy, and the appearance of dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma.

Women with lichen sclerosus occasionally experience discomfort after their clinical skin disease has cleared. These women now have developed vulvodynia triggered by their lichen sclerosus.

Related series: Vulvar Pain Syndromes—A 3-part roundtable

Part 1. Making the correct diagnosis (September 2011)

Part 2. A bounty of treatments—but not all of them proven (October 2011)

Part 3. Causes and treatment of vestibulodynia (November 2011)

CASE 2. IS IT REALLY CHRONIC YEAST INFECTION?

A 36-year-old woman consults you about her history of chronic yeast infection that manifests as introital burning, discharge, and dyspareunia. She is otherwise healthy, except for irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia.

Physical examination reveals a mild patchy redness of the vestibule and surrounding modified mucous membranes (FIGURE 2). Gentle probing with a cotton swab triggers exquisite pain in the vestibule, with slight extension to the labia minora. A wet mount shows no evidence of increased white blood cells, parabasal cells, clue cells, or yeast forms. Lactobacilli are abundant.

Diagnosis: Vulvodynia, with a nearly vestibulodynia pattern.

Treatment: Venlafaxine and pelvic floor physical therapy.

Vulvodynia is a genital pain syndrome defined as sensations of chronic burning, irritation, rawness, and soreness in the absence of objective disease and infection that could explain the discomfort. Vulvodynia occurs in approximately 7% to 8% of women.4

Vulvodynia generally is believed to be a multifactorial symptom, occurring as a result of pelvic floor dysfunction and neuropathic pain,5,6 with anxiety/depression issues exacerbating symptoms. Some recent studies have shown the presence of biochemical mediators of inflammation in the absence of clinical and histologic inflammation.7 Discomfort often is worsened by infections or the application of common irritants (creams, panty liners, soaps, some topical anesthetics). Estrogen deficiency is another common exacerbating factor.

Women tend to exhibit other pain syndromes such as chronic headaches, fibromyalgia, temperomandibular disorder, or premenstrual syndrome, as well as prominent anxiety, depression, sleep disorder, and so on.

Almost uniformly present are symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, such as constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis or urinary symptoms in the absence of a urinary tract infection. These women also are frequently unusually intolerant of medications.

Classifying vulvodynia

There are two primary patterns of vulvodynia. The first and most common is vestibulodynia, formerly called vulvar vestibulitis. The term vestibulitis was eliminated to reflect the absence of clinical and histologic inflammation. Vestibulodynia refers to pain that is always limited to the vestibule. Generalized vulvodynia, however, extends beyond the vestibule, is migratory, or does not include the vestibule.

Several vulvologists have found that many patients exhibit features of both types of vulvodynia, and these patterns probably exist on a spectrum. The difference is probably unimportant in clinical practice, except that vestibulodynia can be treated with vestibulectomy.

How we manage vulvodynia

We focus on pelvic floor physical therapy and on the provision of medication for neuropathic pain, which is initiated at very small doses and gradually increased to active doses.8 The medications used and the ultimate doses often required include:

- amitriptyline or desipramine 150 mg

- gabapentin 600 to 1,200 mg three times daily

- venlafaxine XR 150 mg daily

- pregabalin 150 mg twice a day

- duloxetine 60 mg a day.

Compounded amitriptyline 2% with baclofen 2% cream applied three times daily is beneficial for many patients, and topical lidocaine jelly 2% or ointment 5% (which often burns) can help provide immediate temporary relief.

Most patients require sex therapy and counseling for maximal improvement. Women with vestibulodynia in whom these therapies fail are good candidates for vestibulectomy if their pain is strictly limited to the vestibule. Fortunately, most women do not require this aggressive therapy.

Related article: Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; July 2013)

CASE 3. SEVERE ITCHING DISRUPTS SLEEP

A 34-year-old patient reports excruciating itching, with disruption of daily activities and sleep. She has been treated for candidiasis on multiple occasions, but in your office her wet mount and confirmatory culture are negative. Physical examination reveals a pink, lichenified plaque with excoriation (FIGURE 3).

Diagnosis: Lichen simplex chronicus.

Treatment: Ultra-potent corticosteroid ointment applied very sparingly twice daily and covered with petroleum jelly. You also order nighttime sedation with amitriptyline to break the itch-scratch cycle. When the patient’s itching resolves and her skin clears, you taper her off the corticosteroid, warning her that recurrence is likely, and instruct her to restart the medication immediately should itching recur.

Lichen simplex chronicus (formerly called squamous hyperplasia or hyperplastic dystrophy, and also known as eczema, neurodermatitis, or localized atopic dermatitis) occurs when irritation from any cause produces itching in a predisposed person. The subsequent scratching and rubbing both produce the rash and exacerbate the irritation that drives the itching, even after the original cause is gone. The rubbing and scratching perpetuate the irritation and itching, producing the “itch-scratch” cycle.

The appearance of lichen simplex chronicus is produced by rubbing (where the skin thickens and lichenifies) or scratching (where the skin becomes red with linear erosions, called excoriations, caused by fingernails).

The initial trigger for lichen simplex chronicus often is an infection—often yeast—but overwashing, stress, sweat, heat, urine, irritating lubricants, and use of panty liners also may precipitate the itching. At the office visit, the original infection or other cause of irritation often is no longer present, and only lichen simplex chronicus can be identified.

How to treat lichen simplex chronicus

Management of lichen simplex chronicus requires very sparing application of an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid (clobetasol, halobetasol, or betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle ointment) twice daily, with the ointment covered with petroleum jelly. Care also must be taken to avoid irritants.

In addition, nighttime sedation helps to interrupt the itch-scratch cycle by preventing rubbing during sleep.

When the skin appears normal and itching has resolved, taper the medication down or off, warning the patient that recurrence is common with any future irritation.

Restart therapy immediately upon recurrence to prevent lichenification and chronic problems.

Second-line medications include calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or pimecrolimus). Although these agents do not contribute to atrophy, they are less effective than topical corticosteroids,9 cost more, and can cause burning upon application.

Unlike lichen sclerosus, lichen simplex chronicus does not always recur upon cessation of treatment, and there is no need for concern about an increased risk of malignancy or significant scarring.

Related article: New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (News for your Practice; May 2013)

CASE 4. ORAL AND VULVAR INVOLVEMENT

A 73-year-old patient seeks your help in alleviating longstanding introital itching and rawness, with dyspareunia. She has tried topical estradiol cream intravaginally three times weekly in combination with weekly fluconazole, to no avail.

Physical examination reveals deep red patches and erosions of the vestibule, with complete resorption of the labia minora (FIGURE 4). Patchy redness of the vagina is apparent as well, so you examine the patient’s mouth and find deep redness of the gingivae and erosions of the buccal mucosae, with surrounding white, lacy papules. A wet mount shows a marked increase in lymphocytes and parabasal cells, with a pH of more than 7.

Diagnosis: After correlating the vulvar and oral findings, you make a diagnosis of lichen planus.

Treatment: You initiate halobetasol ointment twice daily, to be applied to the vulva. You also continue vaginal estradiol cream but add hydrocortisone acetate 200 mg compounded vaginal suppositories nightly, as well as clobetasol gel to be applied to oral lesions three times a day. You follow the patient closely for secondary yeast of the mouth and vagina.

Erosive multimucosal lichen planus is a disease of cell-mediated immunity that overwhelmingly affects menopausal women. The most common surfaces involved are the mouth, vagina, rectal mucosa, and vulva; usually, at least two surfaces are affected. The esophagus, extra-auditory canals, nasal mucosa, and eyes also can be involved. Dry, extragenital skin usually is not affected in the setting of erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus.

Vulvar lichen planus most often is controlled with ultra-potent topical corticosteroids (again, clobetasol, halobetasol, or betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle), but other mucosal surfaces often are more difficult to manage. Although there is no definitive cure for this condition, careful local care, estrogen replacement, and suppression of oral and vulvovaginal candidiasis usually provide relief.

Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) sometimes are useful in patients who improve only partially after treatment with a topical corticosteroid, provided burning with application is tolerable.10 Systemic immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha blockers (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab), as well as oral retinoids, can be added for more recalcitrant disease.11

How to manage disease that affects the vagina

When the vagina is involved in lichen planus, treatment is important to prevent scarring, as well as rawness and pain from irritant contact dermatitis caused by purulent vaginal secretions. Occasionally, a 25-mg hydrocortisone acetate rectal suppository inserted into the vagina nightly improves vaginal lichen planus, but sometimes more potent suppositories, such as doses of 100 to 200 mg, may be compounded. Dilators should be inserted daily to prevent vaginal synechiae.

Oral involvement requires targeted treatment

The mouth is almost always involved in lichen planus. If a dermatologist is not involved in patient care, a prescription for dexamethasone/nystatin elixir (50:50) (5 mL swish, hold, and spit four times daily) can improve oral symptoms remarkably. Alternatively, clobetasol gel applied to affected areas of the mouth three or four times daily can be helpful. Secondary yeast of the vagina and mouth are common with the use of topical corticosteroids.

Careful clinical follow-up is advised

Like uncontrolled lichen sclerosus, erosive lichen planus of the vulva produces scarring and sometimes eventuates into squamous cell carcinoma. Therefore, careful clinical surveillance is warranted. And therapy must be continued to prevent recurrence of lichen planus (as it must be for lichen sclerosus), scarring, and to decrease the risk of squamous cell carcinoma. And like lichen sclerosus, lichen planus sometimes triggers vulvodynia.

CASE 5. MULTIPLE BOILS IN THE GROIN

A 31-year-old morbidly obese African American woman comes to your office with continually evolving boils in the groin. A culture shows Bacterioides spp, Escherichia coli, and Peptococcus spp. In the past, multiple courses of various antibiotics have provided only modest relief.

Physical examination reveals fluctuant nodules, scars, and draining sinus tracts of the hair-bearing vulva and crural crease (FIGURE 5). The axillae are clear.

Diagnosis: Hidradenitis suppurativa.

Treatment: The patient begins taking minocycline 100 mg twice daily. Because she is a smoker, you refer her to an aggressive primary care provider for smoking cessation and weight loss management.

Three months later, the patient is developing only about two nodules a month, managed by early intralesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is sometimes called inverse acne because the underlying pathogenesis is similar to cystic acne. Follicular plugging with keratin debris occurs, with additional keratin, sebaceous material, and normal skin bacteria trapped below the occlusion and distending the follicle. As the follicle wall stretches, thins, and allows for leakage of keratin debris into surrounding dermis, a brisk foreign-body response produces a noninfectious abscess.

Hidradenitis suppurativa affects more than 2% of the population.12 It appears only in areas of the body that contain apocrine glands and in individuals who have double- or triple-outlet follicles that predispose them to follicular occlusion. Therefore, this disease has a genetic component.

Other risk factors include male sex, African genetic background, obesity, and smoking. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome is significantly higher in individuals with hidradenitis suppurativa than in the general population.13

Recommended management

Treatments include:

- chronic antibiotics with nonspecific anti-inflammatory activity (tetracyclines, erythromycin, clindamycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole)

- intralesional injection of corticosteroids for early nodules (which often aborts their development)

- TNF alpha blockers (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab)14–16

- surgical removal of affected skin—the definitive therapy.