User login

Sprout Pregnancy Essentials

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

An app to help your patient lose weight (May 2012)

This handy toolkit helps mothers-to-be record important details like weight gain, kicks, and contraction times, with personalized timelines, checklists, comprehensive information about fetal development, and a journaling option.

In this series, I review what I call prescription apps—apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care. Many patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. Often the free apps I recommend to patients are downloaded before they leave my office. When recommending apps, their cost (not necessarily a measure of quality or utility) and platform (device that the app has been designed for) should be taken into account. It is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone.

For moms-to-be: quality information and a tracking tool

When I practiced obstetrics, my group provided patients with a pocket-sized, trifold pregnancy tracker at their first prenatal visit for them to bring to each subsequent appointment. In addition to data such as Rh status and estimated due date, blood pressure, weight, and fundal height were also recorded. The pregnancy tracker served two purposes: 1) a backup mini medical record in case their chart didn’t make it from the medical records department to the clinic on a particular day and 2) a keepsake.

Pregnancy apps take the concept of that little piece of cardboard to a whole new level. One highly rated pregnancy app is Sprout™ Pregnancy Essentials (recommended by Consumer Reports2 and named one of the 50 Best iPhone Apps in 2012 by Time magazine3) from Med ART Studios.4

With Sprout, the user enters her due date and the app automatically tracks the pregnancy week by week. Each time the app is accessed, the screen shows a realistic image of a developing fetus at the appropriate gestational age along with a pregnancy timeline. Tools allow the user to track her weight at each Ob visit. There is also a kick counter as well as a contraction timer for when the time comes.

Each week of the pregnancy is linked to medical information appropriate for the gestational age, such as second trimester screening at week 15 and group B streptococcus testing at week 35. The information is brief, but high-quality, and covers everything from prenatal testing and screening for gestational diabetes to stretch marks and carpal tunnel syndrome. From each topic, the user seamlessly can add preloaded questions to an “M.D. visit planner” or pregnancy-related tasks (such as making an appointment for a glucose challenge test) to a “to do” list.

A free version called Sprout Lite comes in English and Japanese. The premium version for $3.99 is available in English, Spanish, Chinese, German, Italian, Japanese, and Portuguese. The premium version is free of ads; has more advanced images of a developing fetus, with striking graphics; allows the user to share information via Facebook and e-mail; and has a timeline that adjusts to the baby’s gestational age. Both Sprout apps are currently only available for the iPhone and iPad.

Pros. Sprout is easy to use, has beautiful graphics, and the medical information is accurate and accessible. Sprout Lite contains the same high-quality information.

Cons. There is no way to track other medical data in addition to weight, such as fundal height, Rh status, or vaccinations. There is also a price tag to have the app be free of advertisements, get the best graphics, and have a more interactive user experience.

Verdict. It is always nice to be able to recommend a product with high-quality medical information. Sprout Lite always can be road tested first, but for those who live on Facebook, enjoy a more interactive product, hate advertisements, or love impressive graphics, the $3.99 may very well be worth it.

Keep a journal and create a book

While leaving the app with its data on the iPhone or iPad may be enough of a keepsake for some women, those who want to create a pregnancy book can obtain a separate Sprout Pregnancy Journal app-to-book™.5

This app allows the user to write journal entries, upload photos, and then, if desired, download a PDF of the journal or incorporate the beautiful images from the Sprout app to create a bound pregnancy journal (softcover: $19.95 for the first 40 pages; hardcover: $34.95 for the first 40 pages; additional charge for added pages).

The journal app is free to download for a 2-week trial. At the end of 2 weeks there is a choice:

- $4.99 to continue to use the app; includes cloud backup of data

- $7.99 to get cloud backup plus the PDF download (includes a discount for prepaying for the PDF plus $7.99 discount for a print book)

- If the $7.99 prepaid option isn’t chosen at the end of the 2-week trial, the PDF is $9.95.

The Sprout Pregnancy Journal app is available for iPhone, iPad Touch, and iPad.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Why (and how) you should encourage your patients’ search for health information on the Web

(December 2011)

To blog or not to blog? What’s the answer for you and your practice?

(August 2011)

For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online

(March 2011)

Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential

(September 2010)

1. Smith A. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. Pew Internet & American Life Project. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Published March 1, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2012.

2. Morris N. App review: Sprout for iPad and iPhone. Consumer Reports Web site. http://news.consumerreports.org/baby/2011/10/app-review-sprout-for-ipad-and-iphone.html. Published October 10, 2011. Accessed August 13, 2012.

3. Peckham M. 50 best iPhone apps 2012: Pregnancy (Sprout). http://techland.time.com/2012/02/15/50-best-iphone-apps-2012/?iid=tl-article-mostpop1#all. Published February 15, 2012. Accessed August 13, 2012.

4. Sprout Pregnancy Essentials. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

5. Sprout Pregnancy Journal. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-journal-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

An app to help your patient lose weight (May 2012)

This handy toolkit helps mothers-to-be record important details like weight gain, kicks, and contraction times, with personalized timelines, checklists, comprehensive information about fetal development, and a journaling option.

In this series, I review what I call prescription apps—apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care. Many patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. Often the free apps I recommend to patients are downloaded before they leave my office. When recommending apps, their cost (not necessarily a measure of quality or utility) and platform (device that the app has been designed for) should be taken into account. It is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone.

For moms-to-be: quality information and a tracking tool

When I practiced obstetrics, my group provided patients with a pocket-sized, trifold pregnancy tracker at their first prenatal visit for them to bring to each subsequent appointment. In addition to data such as Rh status and estimated due date, blood pressure, weight, and fundal height were also recorded. The pregnancy tracker served two purposes: 1) a backup mini medical record in case their chart didn’t make it from the medical records department to the clinic on a particular day and 2) a keepsake.

Pregnancy apps take the concept of that little piece of cardboard to a whole new level. One highly rated pregnancy app is Sprout™ Pregnancy Essentials (recommended by Consumer Reports2 and named one of the 50 Best iPhone Apps in 2012 by Time magazine3) from Med ART Studios.4

With Sprout, the user enters her due date and the app automatically tracks the pregnancy week by week. Each time the app is accessed, the screen shows a realistic image of a developing fetus at the appropriate gestational age along with a pregnancy timeline. Tools allow the user to track her weight at each Ob visit. There is also a kick counter as well as a contraction timer for when the time comes.

Each week of the pregnancy is linked to medical information appropriate for the gestational age, such as second trimester screening at week 15 and group B streptococcus testing at week 35. The information is brief, but high-quality, and covers everything from prenatal testing and screening for gestational diabetes to stretch marks and carpal tunnel syndrome. From each topic, the user seamlessly can add preloaded questions to an “M.D. visit planner” or pregnancy-related tasks (such as making an appointment for a glucose challenge test) to a “to do” list.

A free version called Sprout Lite comes in English and Japanese. The premium version for $3.99 is available in English, Spanish, Chinese, German, Italian, Japanese, and Portuguese. The premium version is free of ads; has more advanced images of a developing fetus, with striking graphics; allows the user to share information via Facebook and e-mail; and has a timeline that adjusts to the baby’s gestational age. Both Sprout apps are currently only available for the iPhone and iPad.

Pros. Sprout is easy to use, has beautiful graphics, and the medical information is accurate and accessible. Sprout Lite contains the same high-quality information.

Cons. There is no way to track other medical data in addition to weight, such as fundal height, Rh status, or vaccinations. There is also a price tag to have the app be free of advertisements, get the best graphics, and have a more interactive user experience.

Verdict. It is always nice to be able to recommend a product with high-quality medical information. Sprout Lite always can be road tested first, but for those who live on Facebook, enjoy a more interactive product, hate advertisements, or love impressive graphics, the $3.99 may very well be worth it.

Keep a journal and create a book

While leaving the app with its data on the iPhone or iPad may be enough of a keepsake for some women, those who want to create a pregnancy book can obtain a separate Sprout Pregnancy Journal app-to-book™.5

This app allows the user to write journal entries, upload photos, and then, if desired, download a PDF of the journal or incorporate the beautiful images from the Sprout app to create a bound pregnancy journal (softcover: $19.95 for the first 40 pages; hardcover: $34.95 for the first 40 pages; additional charge for added pages).

The journal app is free to download for a 2-week trial. At the end of 2 weeks there is a choice:

- $4.99 to continue to use the app; includes cloud backup of data

- $7.99 to get cloud backup plus the PDF download (includes a discount for prepaying for the PDF plus $7.99 discount for a print book)

- If the $7.99 prepaid option isn’t chosen at the end of the 2-week trial, the PDF is $9.95.

The Sprout Pregnancy Journal app is available for iPhone, iPad Touch, and iPad.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Why (and how) you should encourage your patients’ search for health information on the Web

(December 2011)

To blog or not to blog? What’s the answer for you and your practice?

(August 2011)

For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online

(March 2011)

Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential

(September 2010)

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

An app to help your patient lose weight (May 2012)

This handy toolkit helps mothers-to-be record important details like weight gain, kicks, and contraction times, with personalized timelines, checklists, comprehensive information about fetal development, and a journaling option.

In this series, I review what I call prescription apps—apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care. Many patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. Often the free apps I recommend to patients are downloaded before they leave my office. When recommending apps, their cost (not necessarily a measure of quality or utility) and platform (device that the app has been designed for) should be taken into account. It is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone.

For moms-to-be: quality information and a tracking tool

When I practiced obstetrics, my group provided patients with a pocket-sized, trifold pregnancy tracker at their first prenatal visit for them to bring to each subsequent appointment. In addition to data such as Rh status and estimated due date, blood pressure, weight, and fundal height were also recorded. The pregnancy tracker served two purposes: 1) a backup mini medical record in case their chart didn’t make it from the medical records department to the clinic on a particular day and 2) a keepsake.

Pregnancy apps take the concept of that little piece of cardboard to a whole new level. One highly rated pregnancy app is Sprout™ Pregnancy Essentials (recommended by Consumer Reports2 and named one of the 50 Best iPhone Apps in 2012 by Time magazine3) from Med ART Studios.4

With Sprout, the user enters her due date and the app automatically tracks the pregnancy week by week. Each time the app is accessed, the screen shows a realistic image of a developing fetus at the appropriate gestational age along with a pregnancy timeline. Tools allow the user to track her weight at each Ob visit. There is also a kick counter as well as a contraction timer for when the time comes.

Each week of the pregnancy is linked to medical information appropriate for the gestational age, such as second trimester screening at week 15 and group B streptococcus testing at week 35. The information is brief, but high-quality, and covers everything from prenatal testing and screening for gestational diabetes to stretch marks and carpal tunnel syndrome. From each topic, the user seamlessly can add preloaded questions to an “M.D. visit planner” or pregnancy-related tasks (such as making an appointment for a glucose challenge test) to a “to do” list.

A free version called Sprout Lite comes in English and Japanese. The premium version for $3.99 is available in English, Spanish, Chinese, German, Italian, Japanese, and Portuguese. The premium version is free of ads; has more advanced images of a developing fetus, with striking graphics; allows the user to share information via Facebook and e-mail; and has a timeline that adjusts to the baby’s gestational age. Both Sprout apps are currently only available for the iPhone and iPad.

Pros. Sprout is easy to use, has beautiful graphics, and the medical information is accurate and accessible. Sprout Lite contains the same high-quality information.

Cons. There is no way to track other medical data in addition to weight, such as fundal height, Rh status, or vaccinations. There is also a price tag to have the app be free of advertisements, get the best graphics, and have a more interactive user experience.

Verdict. It is always nice to be able to recommend a product with high-quality medical information. Sprout Lite always can be road tested first, but for those who live on Facebook, enjoy a more interactive product, hate advertisements, or love impressive graphics, the $3.99 may very well be worth it.

Keep a journal and create a book

While leaving the app with its data on the iPhone or iPad may be enough of a keepsake for some women, those who want to create a pregnancy book can obtain a separate Sprout Pregnancy Journal app-to-book™.5

This app allows the user to write journal entries, upload photos, and then, if desired, download a PDF of the journal or incorporate the beautiful images from the Sprout app to create a bound pregnancy journal (softcover: $19.95 for the first 40 pages; hardcover: $34.95 for the first 40 pages; additional charge for added pages).

The journal app is free to download for a 2-week trial. At the end of 2 weeks there is a choice:

- $4.99 to continue to use the app; includes cloud backup of data

- $7.99 to get cloud backup plus the PDF download (includes a discount for prepaying for the PDF plus $7.99 discount for a print book)

- If the $7.99 prepaid option isn’t chosen at the end of the 2-week trial, the PDF is $9.95.

The Sprout Pregnancy Journal app is available for iPhone, iPad Touch, and iPad.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Why (and how) you should encourage your patients’ search for health information on the Web

(December 2011)

To blog or not to blog? What’s the answer for you and your practice?

(August 2011)

For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online

(March 2011)

Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential

(September 2010)

1. Smith A. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. Pew Internet & American Life Project. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Published March 1, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2012.

2. Morris N. App review: Sprout for iPad and iPhone. Consumer Reports Web site. http://news.consumerreports.org/baby/2011/10/app-review-sprout-for-ipad-and-iphone.html. Published October 10, 2011. Accessed August 13, 2012.

3. Peckham M. 50 best iPhone apps 2012: Pregnancy (Sprout). http://techland.time.com/2012/02/15/50-best-iphone-apps-2012/?iid=tl-article-mostpop1#all. Published February 15, 2012. Accessed August 13, 2012.

4. Sprout Pregnancy Essentials. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

5. Sprout Pregnancy Journal. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-journal-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

1. Smith A. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. Pew Internet & American Life Project. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Published March 1, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2012.

2. Morris N. App review: Sprout for iPad and iPhone. Consumer Reports Web site. http://news.consumerreports.org/baby/2011/10/app-review-sprout-for-ipad-and-iphone.html. Published October 10, 2011. Accessed August 13, 2012.

3. Peckham M. 50 best iPhone apps 2012: Pregnancy (Sprout). http://techland.time.com/2012/02/15/50-best-iphone-apps-2012/?iid=tl-article-mostpop1#all. Published February 15, 2012. Accessed August 13, 2012.

4. Sprout Pregnancy Essentials. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

5. Sprout Pregnancy Journal. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-journal-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

An app to help your patient lose weight

HAVE YOU SEEN THESE OTHER APP REVIEWS BY DR. GUNTER?

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

Sprout Pregnancy Essentials: An app to help your patient track her pregnancy (September 2012)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

The increasing use of smartphones among women presents an opportunity to address health issues, such as obesity.

Forty-four percent of US women own a smartphone, according to the latest data.1 Ownership is highest among younger women, with more than 60% of women between the ages of 18 and 34 owning one of these devices.1

One of the features that makes a smartphone, well, smart is the ability to run apps (short for software “applications”). Apps started out as ways to enhance access to email or calendars, but the market has ex-ploded—both demand and supply—so that there are now apps for essentially anything you might ever need. Apple’s app store, the largest, boasts more than 500,000 apps, and more than 25 billion apps had been downloaded by March 2012.2 Medical app developers are keen to capitalize on our ever-increasing “app”-etite.

Medical apps can be divided into two categories: those that can help the patient and those that can help the provider. This series will review what I call prescription apps—in other words, apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care.

Apps are not new to your patients

Many of your patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. I know that my smartphone users are uniformly interested in hearing my recommendations, and it is not uncommon that the free apps I recommend are downloaded before my patient leaves the office.

If you are not an app user yourself, there are two basic things that you should know. First, some apps are free and others are not, although that is not necessarily a measure of quality or utility. Second, apps must be written for the particular device, so it is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone. As of February 2012, the most common devices are the Android (20% of cell phone users), iPhone (19%), and Blackberry (6%).1 Some apps can also be used on tablets (e.g., iPad, Galaxy) and e-book readers (e.g., Nook, Kindle). Use of these devices is also increasing; currently, 29% of Americans own either a tablet or an e-book reader.3

When the clinical need is weight loss

Lose It! is a weight-management app that tracks calories, exercise, and weight. Considering that more than 30% of US women are obese, working toward a healthy weight is a common office discussion and any additional tool is wel-come.4 Journaling, or recording every single thing that is eaten, is a key component of successful dieting. Smartphone users tend to have their phones with them wherever they are, so an app is an ideal tool for the journaling commitment needed for weight loss.

Lose It! is free and works on the following platforms:

- Android

- iPhone

- iPad

- Nook Color

- Nook Tablet.

Advantages include ease of use

The patient need only enter her current weight and height (measure your patient during the visit to ensure that she gets started with accurate numbers), the weight she hopes to attain (you can discuss this as well), and how many pounds she hopes to lose each week, and the app calculates the recommended calorie intake to achieve this goal. The app comes preloaded with thousands of foods, and it enables barcode scanning to upload the food and nutritional content with just a click of the phone’s camera.

The database can be expanded by adding unlisted foods and even recipes. Synchronizing the phone with Loseit.com allows for emailed summaries and reminders when the patient forgets to log a meal. There is also a wide repository of exercises to choose from when logging an activity.

A couple of cons

There is no Lose It! app for the Blackberry—and no plans to write one.

Another disadvantage is the extremely basic exercise journaling (no weekly or review function), and exercise calories are automatically added into the user’s daily allotment—not every dieter wants their calories set up this way.

This is the app I used to journal my 50-lb weight loss (and 6 months of maintenance). I think that testimonial speaks for itself.

In the next installment: an app that reminds your patient to take her birth control pills.

- Why (and how) you should encourage your patients' search for health information on the Web (December 2011)

- Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweight the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception? (Guest Editorial, October 2012)

- To blog or not to blog? What's the answer for you and your practice? (August 2011)

- For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online (March 2011)

- Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential (September 2010)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2012.

2. Apple app store downloads top 25 billion [press release]. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2012/03/05Apples-App-Store-Downloads-Top-25-Billion.html. Accessed April 9, 2012 .

3. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Tablet and e-book reader ownership nearly doubled over the holiday gift-giving period. http://libraries.pewinternet.org/2012/01/23/tablet-and-e-book-reader-ownership-nearly-double-over-the-holiday-gift-giving-period/. Accessed April 9, 2012.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief No. 82; January 2012.

HAVE YOU SEEN THESE OTHER APP REVIEWS BY DR. GUNTER?

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

Sprout Pregnancy Essentials: An app to help your patient track her pregnancy (September 2012)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

The increasing use of smartphones among women presents an opportunity to address health issues, such as obesity.

Forty-four percent of US women own a smartphone, according to the latest data.1 Ownership is highest among younger women, with more than 60% of women between the ages of 18 and 34 owning one of these devices.1

One of the features that makes a smartphone, well, smart is the ability to run apps (short for software “applications”). Apps started out as ways to enhance access to email or calendars, but the market has ex-ploded—both demand and supply—so that there are now apps for essentially anything you might ever need. Apple’s app store, the largest, boasts more than 500,000 apps, and more than 25 billion apps had been downloaded by March 2012.2 Medical app developers are keen to capitalize on our ever-increasing “app”-etite.

Medical apps can be divided into two categories: those that can help the patient and those that can help the provider. This series will review what I call prescription apps—in other words, apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care.

Apps are not new to your patients

Many of your patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. I know that my smartphone users are uniformly interested in hearing my recommendations, and it is not uncommon that the free apps I recommend are downloaded before my patient leaves the office.

If you are not an app user yourself, there are two basic things that you should know. First, some apps are free and others are not, although that is not necessarily a measure of quality or utility. Second, apps must be written for the particular device, so it is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone. As of February 2012, the most common devices are the Android (20% of cell phone users), iPhone (19%), and Blackberry (6%).1 Some apps can also be used on tablets (e.g., iPad, Galaxy) and e-book readers (e.g., Nook, Kindle). Use of these devices is also increasing; currently, 29% of Americans own either a tablet or an e-book reader.3

When the clinical need is weight loss

Lose It! is a weight-management app that tracks calories, exercise, and weight. Considering that more than 30% of US women are obese, working toward a healthy weight is a common office discussion and any additional tool is wel-come.4 Journaling, or recording every single thing that is eaten, is a key component of successful dieting. Smartphone users tend to have their phones with them wherever they are, so an app is an ideal tool for the journaling commitment needed for weight loss.

Lose It! is free and works on the following platforms:

- Android

- iPhone

- iPad

- Nook Color

- Nook Tablet.

Advantages include ease of use

The patient need only enter her current weight and height (measure your patient during the visit to ensure that she gets started with accurate numbers), the weight she hopes to attain (you can discuss this as well), and how many pounds she hopes to lose each week, and the app calculates the recommended calorie intake to achieve this goal. The app comes preloaded with thousands of foods, and it enables barcode scanning to upload the food and nutritional content with just a click of the phone’s camera.

The database can be expanded by adding unlisted foods and even recipes. Synchronizing the phone with Loseit.com allows for emailed summaries and reminders when the patient forgets to log a meal. There is also a wide repository of exercises to choose from when logging an activity.

A couple of cons

There is no Lose It! app for the Blackberry—and no plans to write one.

Another disadvantage is the extremely basic exercise journaling (no weekly or review function), and exercise calories are automatically added into the user’s daily allotment—not every dieter wants their calories set up this way.

This is the app I used to journal my 50-lb weight loss (and 6 months of maintenance). I think that testimonial speaks for itself.

In the next installment: an app that reminds your patient to take her birth control pills.

- Why (and how) you should encourage your patients' search for health information on the Web (December 2011)

- Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweight the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception? (Guest Editorial, October 2012)

- To blog or not to blog? What's the answer for you and your practice? (August 2011)

- For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online (March 2011)

- Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential (September 2010)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

HAVE YOU SEEN THESE OTHER APP REVIEWS BY DR. GUNTER?

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

Sprout Pregnancy Essentials: An app to help your patient track her pregnancy (September 2012)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

The increasing use of smartphones among women presents an opportunity to address health issues, such as obesity.

Forty-four percent of US women own a smartphone, according to the latest data.1 Ownership is highest among younger women, with more than 60% of women between the ages of 18 and 34 owning one of these devices.1

One of the features that makes a smartphone, well, smart is the ability to run apps (short for software “applications”). Apps started out as ways to enhance access to email or calendars, but the market has ex-ploded—both demand and supply—so that there are now apps for essentially anything you might ever need. Apple’s app store, the largest, boasts more than 500,000 apps, and more than 25 billion apps had been downloaded by March 2012.2 Medical app developers are keen to capitalize on our ever-increasing “app”-etite.

Medical apps can be divided into two categories: those that can help the patient and those that can help the provider. This series will review what I call prescription apps—in other words, apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care.

Apps are not new to your patients

Many of your patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. I know that my smartphone users are uniformly interested in hearing my recommendations, and it is not uncommon that the free apps I recommend are downloaded before my patient leaves the office.

If you are not an app user yourself, there are two basic things that you should know. First, some apps are free and others are not, although that is not necessarily a measure of quality or utility. Second, apps must be written for the particular device, so it is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone. As of February 2012, the most common devices are the Android (20% of cell phone users), iPhone (19%), and Blackberry (6%).1 Some apps can also be used on tablets (e.g., iPad, Galaxy) and e-book readers (e.g., Nook, Kindle). Use of these devices is also increasing; currently, 29% of Americans own either a tablet or an e-book reader.3

When the clinical need is weight loss

Lose It! is a weight-management app that tracks calories, exercise, and weight. Considering that more than 30% of US women are obese, working toward a healthy weight is a common office discussion and any additional tool is wel-come.4 Journaling, or recording every single thing that is eaten, is a key component of successful dieting. Smartphone users tend to have their phones with them wherever they are, so an app is an ideal tool for the journaling commitment needed for weight loss.

Lose It! is free and works on the following platforms:

- Android

- iPhone

- iPad

- Nook Color

- Nook Tablet.

Advantages include ease of use

The patient need only enter her current weight and height (measure your patient during the visit to ensure that she gets started with accurate numbers), the weight she hopes to attain (you can discuss this as well), and how many pounds she hopes to lose each week, and the app calculates the recommended calorie intake to achieve this goal. The app comes preloaded with thousands of foods, and it enables barcode scanning to upload the food and nutritional content with just a click of the phone’s camera.

The database can be expanded by adding unlisted foods and even recipes. Synchronizing the phone with Loseit.com allows for emailed summaries and reminders when the patient forgets to log a meal. There is also a wide repository of exercises to choose from when logging an activity.

A couple of cons

There is no Lose It! app for the Blackberry—and no plans to write one.

Another disadvantage is the extremely basic exercise journaling (no weekly or review function), and exercise calories are automatically added into the user’s daily allotment—not every dieter wants their calories set up this way.

This is the app I used to journal my 50-lb weight loss (and 6 months of maintenance). I think that testimonial speaks for itself.

In the next installment: an app that reminds your patient to take her birth control pills.

- Why (and how) you should encourage your patients' search for health information on the Web (December 2011)

- Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweight the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception? (Guest Editorial, October 2012)

- To blog or not to blog? What's the answer for you and your practice? (August 2011)

- For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online (March 2011)

- Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential (September 2010)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2012.

2. Apple app store downloads top 25 billion [press release]. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2012/03/05Apples-App-Store-Downloads-Top-25-Billion.html. Accessed April 9, 2012 .

3. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Tablet and e-book reader ownership nearly doubled over the holiday gift-giving period. http://libraries.pewinternet.org/2012/01/23/tablet-and-e-book-reader-ownership-nearly-double-over-the-holiday-gift-giving-period/. Accessed April 9, 2012.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief No. 82; January 2012.

1. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2012.

2. Apple app store downloads top 25 billion [press release]. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2012/03/05Apples-App-Store-Downloads-Top-25-Billion.html. Accessed April 9, 2012 .

3. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Tablet and e-book reader ownership nearly doubled over the holiday gift-giving period. http://libraries.pewinternet.org/2012/01/23/tablet-and-e-book-reader-ownership-nearly-double-over-the-holiday-gift-giving-period/. Accessed April 9, 2012.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief No. 82; January 2012.

Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweigh the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception?

Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

Let’s increase our use of implants and DMPA and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2012)

It is well established that combined hormonal contraception increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), both deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).1 Concerns exist that drospirenone-containing combined oral contraceptives (OCs), the norelgestromin patch, and the etonogestrel vaginal ring may increase the risk of VTE, compared with second-generation OCs, although results from studies evaluating the thromboembolic risk of these products are conflicting.1,2

An April 2012 safety communication from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported that “drospirenone-containing birth control pills may be associated with a higher risk for blood clots than other progestin-containing pills.”3 These pills now carry revised drug labels stating that epidemiologic studies that compared the risk of VTE reported that the risk ranged from no increase to a three-fold increase.3

Together, these studies and the FDA warning have garnered a lot of publicity and caused confusion and concern, leading both patients and providers to ask, “Are these specific products really safe?”

What is the baseline risk?

For nonusers of hormonal contraception, the baseline risk of VTE is 1 to 5 events per 10,000 woman-years.1,3-5 Variables that increase a woman’s risk of VTE include1:

- advanced age

- obesity

- immobility

- hematologic disorders

- pregnancy.

Estrogen-containing OCs with second-generation progestins (levonorgestrel, norgestimate, and norethindrone) have a risk of VTE of approximately 3 to 9 events per 10,000 woman-years.1,3-5

When study results conflict

The relative risk of VTE associated with drospirenone-containing OCs, compared with second-generation pills, ranges from 0.9 to 3.3. The relative risk is 1.2 to 2.2 for the norelgestromin patch, and 1.6 to 1.9 for the etonogestrel ring.1-4

All of the studies addressing the increased risk of VTE with drospirenone, the patch, and the ring have some limitations, such as the use of retrospective data, selection bias, study design, or inclusion of multiple pill regimens. However, most of the studies that found no association between these methods and VTE were industry-funded.2 Criticisms of these studies have led to disagreement about the risk; it is unclear whether a definitive study ever can be designed and performed.2

Worst-case scenario. Using data from only those studies that show an increased risk of VTE, the increased number of VTE events above that conferred by a second-generation progestin would be approximately2:

- ring: 3–5/10,000 woman-years

- patch: 3–8/10,000 woman-years

- drospirenone pill: 5–10/10,000 woman-years (risk may be highest in the first year of use3).

Adding perspective

The risks of hormonal contraception must be weighed against the consequences of using no contraception: 43 million women in the United States are sexually active but do not wish to become pregnant. Without contraception, 85% will be pregnant within 1 year.6 The risk of mortality during pregnancy in the United States is 1.8 deaths per 10,000 live births (5.5 deaths per 10,000 live births for women older than 39 years).7The prevalence of VTE during pregnancy is 5 to 29 events per 10,000 women; during the postpartum period, the prevalence is 40 to 65 events per 10,000 women (although some quote the VTE risk during the postpartum period to be as high as 200 to 400 events per 10,000 women).3,5,8

An unplanned pregnancy is more likely than a planned pregnancy to have a poor perinatal outcome or to end in abortion. The socioeconomic benefits of planning pregnancies must also be considered.

Hormonal contraception confers benefits beyond the prevention of pregnancy. In addition to a 50% reduction in the rate of endometrial cancer and a 27% reduction in the rate of ovarian cancer (and an even greater reduction for women who take OCs longer than 5 years), there are other benefits to hormonal contraception, such as reduced acne, dysmenorrhea, and menorrhagia.9

Individualize your care

When choosing a method of contraception, it is important not only to consider thromboembolic risk but also:

- previous contraceptive experiences

- previous pregnancies

- patient preference

- efficacy

- individual health factors

- cost.

For instance, even though the risk of VTE may be slightly increased among women using the norelgestromin patch, compliance rates are higher with the patch than with the pill.10 A woman with two unplanned pregnancies while taking the pill who reports having difficulty adhering to a daily regimen is a different patch candidate than a woman who has successfully planned two pregnancies using OCs.

For many women, a weekly or monthly reversible contraceptive is the most desirable method. In addition to these more quantifiable factors, some women prefer a specific brand of pill or delivery method—and satisfaction is a key component of contraception adherence.

Educate your patient

I favor the approach of providing as much data as possible. Patients may read the black box warning in the package inserts for drospirenone-containing pills or the norelgestromin patch, find news sources that inaccurately report risk to garner the most compelling headline, or stumble across plaintiff’s lawyers advertising lawsuits for drospirenone-containing pills, the contraceptive ring, and the patch. I can best counter confusion or misinformation by providing accurate information and putting possible risks into perspective up front. I now explain that the risk for VTE may be higher with certain pills, the ring, and the patch, but there just aren’t enough high-quality data to be certain. I also explain that risk may mean different things for different patients, based on medical history and previous experiences. I have found that my patients appreciate the full disclosure.

Overall, the benefits of combined hormonal contraception with all methods outweigh the risk of VTE. In addition, issues related to switching contraceptive methods may increase the risk of an unplanned pregnancy. In 1995, when the United Kingdom warned that desogestrel pills carried an increased risk of VTE but were still “safe,” the incidence of unplanned pregnancies and abortions increased.2,11 The data regarding the risk of VTE associated with drospirenone, the patch, and the ring should not be an impetus for sweeping generalizations, but rather an opportunity to educate our patients (and ourselves) and to further individualize care.

Do you agree that the benefits of combined hormonal contraception with all methods outweigh the VTE risk? Why or why not? What do you do in your practice? Click here

Click here to find additional articles on contraception published in OBG Management

in 2012.

1. Lidegaard Ø, Milsom I, Geirsson R, Skjeldestad F. Hormonal contraception and venous thromboembolism. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(7):769-778.

2. Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1039-1044.

3. US Food and Drug Administration. Safety Announcement. Updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Published April 10 2012. Accessed September 11, 2012.

4. Lidegaard Ø, Nielsen L, Skovlund C, Løkkegaard E. Venous thrombosis in users of non-oral hormonal contraception: follow-up study Denmark 2001-10 [published online ahead of print May 10, 2012]. BMJ. 2012:344-353:e2990. doi: 10.1136 /bmj.e2990.

5. Oral contraceptives and the risk of thromboembolism: an update. Clinical practice Guideline No. 252. Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. 2010;252. http://www.sogc.org/guidelines/documents/gui252CPG1012E.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2012.

6. Fact Sheet Contraceptive use in the United States. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_contr_use.html. Published July 2012. Accessed September 5 2012.

7. Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy related mortality in the United States 1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1302-1309.

8. James A. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 123. Thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):718-729.

9. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 110. Noncontraceptive uses of hormonal contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):206-218.

10. Archer DF, Bigrigg A, Smallwood GH, Shangold GA, Creasy GW, Fisher AC. Assessment of compliance with a weekly contraceptive patch (OrthoEvra/Evra) among North American women. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(2 suppl 2):S27-S31.

11. Furedi A. The public health implications of the 1995 ‘pill scare.’ Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5(6):621-626.

Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

Let’s increase our use of implants and DMPA and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2012)

It is well established that combined hormonal contraception increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), both deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).1 Concerns exist that drospirenone-containing combined oral contraceptives (OCs), the norelgestromin patch, and the etonogestrel vaginal ring may increase the risk of VTE, compared with second-generation OCs, although results from studies evaluating the thromboembolic risk of these products are conflicting.1,2

An April 2012 safety communication from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported that “drospirenone-containing birth control pills may be associated with a higher risk for blood clots than other progestin-containing pills.”3 These pills now carry revised drug labels stating that epidemiologic studies that compared the risk of VTE reported that the risk ranged from no increase to a three-fold increase.3

Together, these studies and the FDA warning have garnered a lot of publicity and caused confusion and concern, leading both patients and providers to ask, “Are these specific products really safe?”

What is the baseline risk?

For nonusers of hormonal contraception, the baseline risk of VTE is 1 to 5 events per 10,000 woman-years.1,3-5 Variables that increase a woman’s risk of VTE include1:

- advanced age

- obesity

- immobility

- hematologic disorders

- pregnancy.

Estrogen-containing OCs with second-generation progestins (levonorgestrel, norgestimate, and norethindrone) have a risk of VTE of approximately 3 to 9 events per 10,000 woman-years.1,3-5

When study results conflict

The relative risk of VTE associated with drospirenone-containing OCs, compared with second-generation pills, ranges from 0.9 to 3.3. The relative risk is 1.2 to 2.2 for the norelgestromin patch, and 1.6 to 1.9 for the etonogestrel ring.1-4

All of the studies addressing the increased risk of VTE with drospirenone, the patch, and the ring have some limitations, such as the use of retrospective data, selection bias, study design, or inclusion of multiple pill regimens. However, most of the studies that found no association between these methods and VTE were industry-funded.2 Criticisms of these studies have led to disagreement about the risk; it is unclear whether a definitive study ever can be designed and performed.2

Worst-case scenario. Using data from only those studies that show an increased risk of VTE, the increased number of VTE events above that conferred by a second-generation progestin would be approximately2:

- ring: 3–5/10,000 woman-years

- patch: 3–8/10,000 woman-years

- drospirenone pill: 5–10/10,000 woman-years (risk may be highest in the first year of use3).

Adding perspective

The risks of hormonal contraception must be weighed against the consequences of using no contraception: 43 million women in the United States are sexually active but do not wish to become pregnant. Without contraception, 85% will be pregnant within 1 year.6 The risk of mortality during pregnancy in the United States is 1.8 deaths per 10,000 live births (5.5 deaths per 10,000 live births for women older than 39 years).7The prevalence of VTE during pregnancy is 5 to 29 events per 10,000 women; during the postpartum period, the prevalence is 40 to 65 events per 10,000 women (although some quote the VTE risk during the postpartum period to be as high as 200 to 400 events per 10,000 women).3,5,8

An unplanned pregnancy is more likely than a planned pregnancy to have a poor perinatal outcome or to end in abortion. The socioeconomic benefits of planning pregnancies must also be considered.

Hormonal contraception confers benefits beyond the prevention of pregnancy. In addition to a 50% reduction in the rate of endometrial cancer and a 27% reduction in the rate of ovarian cancer (and an even greater reduction for women who take OCs longer than 5 years), there are other benefits to hormonal contraception, such as reduced acne, dysmenorrhea, and menorrhagia.9

Individualize your care

When choosing a method of contraception, it is important not only to consider thromboembolic risk but also:

- previous contraceptive experiences

- previous pregnancies

- patient preference

- efficacy

- individual health factors

- cost.

For instance, even though the risk of VTE may be slightly increased among women using the norelgestromin patch, compliance rates are higher with the patch than with the pill.10 A woman with two unplanned pregnancies while taking the pill who reports having difficulty adhering to a daily regimen is a different patch candidate than a woman who has successfully planned two pregnancies using OCs.

For many women, a weekly or monthly reversible contraceptive is the most desirable method. In addition to these more quantifiable factors, some women prefer a specific brand of pill or delivery method—and satisfaction is a key component of contraception adherence.

Educate your patient

I favor the approach of providing as much data as possible. Patients may read the black box warning in the package inserts for drospirenone-containing pills or the norelgestromin patch, find news sources that inaccurately report risk to garner the most compelling headline, or stumble across plaintiff’s lawyers advertising lawsuits for drospirenone-containing pills, the contraceptive ring, and the patch. I can best counter confusion or misinformation by providing accurate information and putting possible risks into perspective up front. I now explain that the risk for VTE may be higher with certain pills, the ring, and the patch, but there just aren’t enough high-quality data to be certain. I also explain that risk may mean different things for different patients, based on medical history and previous experiences. I have found that my patients appreciate the full disclosure.

Overall, the benefits of combined hormonal contraception with all methods outweigh the risk of VTE. In addition, issues related to switching contraceptive methods may increase the risk of an unplanned pregnancy. In 1995, when the United Kingdom warned that desogestrel pills carried an increased risk of VTE but were still “safe,” the incidence of unplanned pregnancies and abortions increased.2,11 The data regarding the risk of VTE associated with drospirenone, the patch, and the ring should not be an impetus for sweeping generalizations, but rather an opportunity to educate our patients (and ourselves) and to further individualize care.

Do you agree that the benefits of combined hormonal contraception with all methods outweigh the VTE risk? Why or why not? What do you do in your practice? Click here

Click here to find additional articles on contraception published in OBG Management

in 2012.

Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

Let’s increase our use of implants and DMPA and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2012)

It is well established that combined hormonal contraception increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), both deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).1 Concerns exist that drospirenone-containing combined oral contraceptives (OCs), the norelgestromin patch, and the etonogestrel vaginal ring may increase the risk of VTE, compared with second-generation OCs, although results from studies evaluating the thromboembolic risk of these products are conflicting.1,2

An April 2012 safety communication from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported that “drospirenone-containing birth control pills may be associated with a higher risk for blood clots than other progestin-containing pills.”3 These pills now carry revised drug labels stating that epidemiologic studies that compared the risk of VTE reported that the risk ranged from no increase to a three-fold increase.3

Together, these studies and the FDA warning have garnered a lot of publicity and caused confusion and concern, leading both patients and providers to ask, “Are these specific products really safe?”

What is the baseline risk?

For nonusers of hormonal contraception, the baseline risk of VTE is 1 to 5 events per 10,000 woman-years.1,3-5 Variables that increase a woman’s risk of VTE include1:

- advanced age

- obesity

- immobility

- hematologic disorders

- pregnancy.

Estrogen-containing OCs with second-generation progestins (levonorgestrel, norgestimate, and norethindrone) have a risk of VTE of approximately 3 to 9 events per 10,000 woman-years.1,3-5

When study results conflict

The relative risk of VTE associated with drospirenone-containing OCs, compared with second-generation pills, ranges from 0.9 to 3.3. The relative risk is 1.2 to 2.2 for the norelgestromin patch, and 1.6 to 1.9 for the etonogestrel ring.1-4

All of the studies addressing the increased risk of VTE with drospirenone, the patch, and the ring have some limitations, such as the use of retrospective data, selection bias, study design, or inclusion of multiple pill regimens. However, most of the studies that found no association between these methods and VTE were industry-funded.2 Criticisms of these studies have led to disagreement about the risk; it is unclear whether a definitive study ever can be designed and performed.2

Worst-case scenario. Using data from only those studies that show an increased risk of VTE, the increased number of VTE events above that conferred by a second-generation progestin would be approximately2:

- ring: 3–5/10,000 woman-years

- patch: 3–8/10,000 woman-years

- drospirenone pill: 5–10/10,000 woman-years (risk may be highest in the first year of use3).

Adding perspective

The risks of hormonal contraception must be weighed against the consequences of using no contraception: 43 million women in the United States are sexually active but do not wish to become pregnant. Without contraception, 85% will be pregnant within 1 year.6 The risk of mortality during pregnancy in the United States is 1.8 deaths per 10,000 live births (5.5 deaths per 10,000 live births for women older than 39 years).7The prevalence of VTE during pregnancy is 5 to 29 events per 10,000 women; during the postpartum period, the prevalence is 40 to 65 events per 10,000 women (although some quote the VTE risk during the postpartum period to be as high as 200 to 400 events per 10,000 women).3,5,8

An unplanned pregnancy is more likely than a planned pregnancy to have a poor perinatal outcome or to end in abortion. The socioeconomic benefits of planning pregnancies must also be considered.

Hormonal contraception confers benefits beyond the prevention of pregnancy. In addition to a 50% reduction in the rate of endometrial cancer and a 27% reduction in the rate of ovarian cancer (and an even greater reduction for women who take OCs longer than 5 years), there are other benefits to hormonal contraception, such as reduced acne, dysmenorrhea, and menorrhagia.9

Individualize your care

When choosing a method of contraception, it is important not only to consider thromboembolic risk but also:

- previous contraceptive experiences

- previous pregnancies

- patient preference

- efficacy

- individual health factors

- cost.

For instance, even though the risk of VTE may be slightly increased among women using the norelgestromin patch, compliance rates are higher with the patch than with the pill.10 A woman with two unplanned pregnancies while taking the pill who reports having difficulty adhering to a daily regimen is a different patch candidate than a woman who has successfully planned two pregnancies using OCs.

For many women, a weekly or monthly reversible contraceptive is the most desirable method. In addition to these more quantifiable factors, some women prefer a specific brand of pill or delivery method—and satisfaction is a key component of contraception adherence.

Educate your patient

I favor the approach of providing as much data as possible. Patients may read the black box warning in the package inserts for drospirenone-containing pills or the norelgestromin patch, find news sources that inaccurately report risk to garner the most compelling headline, or stumble across plaintiff’s lawyers advertising lawsuits for drospirenone-containing pills, the contraceptive ring, and the patch. I can best counter confusion or misinformation by providing accurate information and putting possible risks into perspective up front. I now explain that the risk for VTE may be higher with certain pills, the ring, and the patch, but there just aren’t enough high-quality data to be certain. I also explain that risk may mean different things for different patients, based on medical history and previous experiences. I have found that my patients appreciate the full disclosure.

Overall, the benefits of combined hormonal contraception with all methods outweigh the risk of VTE. In addition, issues related to switching contraceptive methods may increase the risk of an unplanned pregnancy. In 1995, when the United Kingdom warned that desogestrel pills carried an increased risk of VTE but were still “safe,” the incidence of unplanned pregnancies and abortions increased.2,11 The data regarding the risk of VTE associated with drospirenone, the patch, and the ring should not be an impetus for sweeping generalizations, but rather an opportunity to educate our patients (and ourselves) and to further individualize care.

Do you agree that the benefits of combined hormonal contraception with all methods outweigh the VTE risk? Why or why not? What do you do in your practice? Click here

Click here to find additional articles on contraception published in OBG Management

in 2012.

1. Lidegaard Ø, Milsom I, Geirsson R, Skjeldestad F. Hormonal contraception and venous thromboembolism. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(7):769-778.

2. Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1039-1044.

3. US Food and Drug Administration. Safety Announcement. Updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Published April 10 2012. Accessed September 11, 2012.

4. Lidegaard Ø, Nielsen L, Skovlund C, Løkkegaard E. Venous thrombosis in users of non-oral hormonal contraception: follow-up study Denmark 2001-10 [published online ahead of print May 10, 2012]. BMJ. 2012:344-353:e2990. doi: 10.1136 /bmj.e2990.

5. Oral contraceptives and the risk of thromboembolism: an update. Clinical practice Guideline No. 252. Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. 2010;252. http://www.sogc.org/guidelines/documents/gui252CPG1012E.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2012.

6. Fact Sheet Contraceptive use in the United States. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_contr_use.html. Published July 2012. Accessed September 5 2012.

7. Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy related mortality in the United States 1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1302-1309.

8. James A. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 123. Thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):718-729.

9. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 110. Noncontraceptive uses of hormonal contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):206-218.

10. Archer DF, Bigrigg A, Smallwood GH, Shangold GA, Creasy GW, Fisher AC. Assessment of compliance with a weekly contraceptive patch (OrthoEvra/Evra) among North American women. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(2 suppl 2):S27-S31.

11. Furedi A. The public health implications of the 1995 ‘pill scare.’ Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5(6):621-626.

1. Lidegaard Ø, Milsom I, Geirsson R, Skjeldestad F. Hormonal contraception and venous thromboembolism. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(7):769-778.

2. Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1039-1044.

3. US Food and Drug Administration. Safety Announcement. Updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Published April 10 2012. Accessed September 11, 2012.

4. Lidegaard Ø, Nielsen L, Skovlund C, Løkkegaard E. Venous thrombosis in users of non-oral hormonal contraception: follow-up study Denmark 2001-10 [published online ahead of print May 10, 2012]. BMJ. 2012:344-353:e2990. doi: 10.1136 /bmj.e2990.

5. Oral contraceptives and the risk of thromboembolism: an update. Clinical practice Guideline No. 252. Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. 2010;252. http://www.sogc.org/guidelines/documents/gui252CPG1012E.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2012.

6. Fact Sheet Contraceptive use in the United States. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_contr_use.html. Published July 2012. Accessed September 5 2012.

7. Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy related mortality in the United States 1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1302-1309.

8. James A. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 123. Thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):718-729.

9. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 110. Noncontraceptive uses of hormonal contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):206-218.

10. Archer DF, Bigrigg A, Smallwood GH, Shangold GA, Creasy GW, Fisher AC. Assessment of compliance with a weekly contraceptive patch (OrthoEvra/Evra) among North American women. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(2 suppl 2):S27-S31.

11. Furedi A. The public health implications of the 1995 ‘pill scare.’ Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5(6):621-626.

Vulvar pain syndromes: Making the correct diagnosis

Although the incidence of vulvar pain has increased over the past decade—thanks to both greater awareness and increasing numbers of affected women—the phenomenon is not a recent development. As early as 1874, T. Galliard Thomas wrote, “[T]his disorder, although fortunately not very frequent, is by no means very rare.”1 He went on to express “surprise” that it had not been “more generally and fully described.”

Despite the focus Thomas directed to the issue, vulvar pain did not get much attention until the 21st century, when a number of studies began to gauge its prevalence. For example, in a study in Boston of about 5,000 women, the lifetime prevalence of chronic vulvar pain was 16%.2 And in a study in Texas, the prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban, largely minority population was estimated to be 11%.3 The Boston study also reported that “nearly 40% of women chose not to seek treatment, and, of those who did, 60% saw three or more doctors, many of whom could not provide a diagnosis.”2

Clearly, there is a need for comprehensive information on vulvar pain and its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. To address the lack of guidance, OBG Management Contributing Editor Neal M. Lonky, MD, assembled a panel of experts on vulvar pain syndromes and invited them to share their considerable knowledge. The ensuing discussion, presented in three parts, offers a gold mine of information. In this opening article, the panel focuses on causes, symptomatology, and diagnosis of this common complaint.

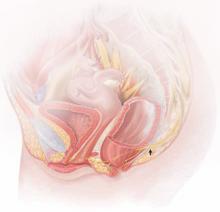

|

The lower vagina and vulva are richly supplied with peripheral nerves and are, therefore, sensitive to pain, particularly the region of the hymeneal ring. Although the pudendal nerve (arrow) courses through the area, it is an uncommon source of vulvar pain. |

![]()

Dr. Lonky: What are the most common diagnoses when vulvar pain is the complaint?

Dr. Gunter: The most common cause of chronic vulvar pain is vulvodynia, although lichen simplex chronicus, chronic yeast infections, and non-neoplastic epithelial disorders, such as lichen sclerosus and lichen planus, can also produce irritation and pain. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis can also cause a burning pain, although symptoms are typically more vaginal than vulvar. Yeast and lichen simplex chronicus typically produce itching, although sometimes they can present with irritation and pain, so they must be considered in the differential diagnosis. It is important to remember that many women with vulvodynia have used multiple topical agents and may have developed complex hygiene rituals in an attempt to treat their symptoms, which can result in a secondary lichen simplex chronicus.

That said, there is a high frequency of misdiagnosis with yeast. For example, in a study by Nyirjesy and colleagues, two thirds of women who were referred to a tertiary clinic for chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis were found to have a noninfectious entity instead—most commonly lichen simplex chronicus and vulvodynia.4

Dr. Edwards: The most common “diagnosis” for vulvar pain is vulvodynia. However, the definition of vulvodynia is pain—i.e., burning, rawness, irritation, soreness, aching, or stabbing or stinging sensations—in the absence of skin disease, infection, or specific neurologic disease. Therefore, even though the usual cause of vulvar pain is vulvodynia, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, and skin disease, infection, and neurologic disease must be ruled out.

In regard to infection, Candida albicans and bacterial vaginosis (BV) are usually the first conditions that are considered when a patient complains of vulvar pain, but they are not common causes of vulvar pain and are never causes of chronic vulvar pain. Very rarely they may cause recurrent pain that clears, at least briefly, with treatment.

Candida albicans is usually primarily pruritic, and BV produces discharge and odor, sometimes with minor symptoms. Non-albicans Candida (e.g., Candida glabrata) is nearly always asymptomatic, but it occasionally causes irritation and burning.

Group B streptococcus is another infectious entity that very, very occasionally causes irritation and dyspareunia but is usually only a colonizer.

Herpes simplex virus is a cause of recurrent but not chronic pain.

Chronic pain is more likely to be caused by skin disease than by infection. Lichen simplex chronicus causes itching; any pain is due to erosions from scratching.

Dr. Haefner: Several other infectious conditions or their treatments can cause vulvar pain. For example, herpes (particularly primary herpes infection) is classically associated with vulvar pain. The pain is so great that, at times, the patient requires admission for pain control. Surprisingly, despite the known pain of herpes, approximately 80% of patients who have it are unaware of their diagnosis.

Although condyloma is generally a painless condition, many patients complain of pain following treatment for it, whether treatment involves topical medications or laser surgery.

Chancroid is a painful vulvar ulcer. Trichomonas can sometimes be associated with vulvar pain.

Dr. Lonky: What terminology do we use when we discuss vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: The current terminology used to describe vulvar pain was published in 2004, after years of debate over nomenclature within the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease.5 The terminology lists two major categories of vulvar pain:

-

pain related to a specific disorder. This category encompasses numerous conditions that feature an abnormal appearance of the vulva (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Terminology and classification of vulvar pain from the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease

| SOURCE: Moyal-Barracco and Lynch.5 Reproduced with permission from the Journal of Reproductive Medicine. |

|

-

vulvodynia, in which the vulva appears normal, other than occasional erythema, which is most prominent at the duct openings (vestibular ducts—Bartholin’s and Skene’s).

As for vulvar pain, there are two major forms:

-

hyperalgesia (a low threshold for pain)

-

allodynia (pain in response to light touch).

Some diseases that are associated with vulvar pain do not qualify for the diagnosis of vulvodynia (Table 2) because they are associated with an abnormal appearance of the vulva.

TABLE 2

Conditions other than vulvodynia that are associated with vulvar pain

| Acute irritant contact dermatitis (e.g., erosion due to podofilox, imiquimod, cantharidin, fluorouracil, or podophyllin toxin) |

| Aphthous ulcer |

| Atrophy |

| Bartholin’s abscess |

| Candidiasis |

| Carcinoma |

| Chronic irritant contact dermatitis |

| Endometriosis |

| Herpes (simplex and zoster) |

| Immunobullous diseases (including cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, linear immunoglobulin A disease, etc.) |

| Lichen planus |

| Lichen sclerosus |

| Podophyllin overdose (see above) |

| Prolapsed urethra |

| Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Trauma |

| Trichomoniasis |

| Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia |

![]()

Dr. Lonky: What skin diseases need to be ruled out before vulvodynia can be diagnosed?

Dr. Edwards: Skin diseases that affect the vulva are usually pruritic—pain is a later sign. Lichen simplex chronicus (also known as eczema) is pruritus caused by any irritant; any pain that arises is produced by visible excoriations from scratching.

Lichen sclerosus manifests as white epithelium that has a crinkling, shiny, or waxy texture. It can produce pain, especially dyspareunia. The pain is caused by erosions that arise from fragility and introital narrowing and inelasticity.

Vulvovaginal lichen planus is usually erosive and preferentially affects mucous membranes, especially the vestibule; it sometimes affects the vagina and mouth, as well.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is most likely a skin disease that affects only the vagina. It involves introital redness and a clinically and microscopically purulent vaginal discharge that also reveals parabasal cells and absent lactobacilli.

Dr. Lonky: You mentioned that neurologic diseases can sometimes cause vulvar pain. Which ones?

Dr. Edwards: Pudendal neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, and post-herpetic neuralgia are the most common specific neurologic causes of vulvar pain. Multiple sclerosis can also produce pain syndromes. Post-herpetic neuralgia follows herpes zoster—not herpes simplex—virus infection.

Dr. Lonky: Any other conditions that can cause vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: Aphthous ulcers are common and are often flared by stress.

Non-neoplastic epithelial disorders are also seen frequently in health-care providers’ offices; many patients who experience them report pain on the vulva.

It is always important to consider cancer when a patient has an abnormal vulvar appearance and pain that has persisted despite treatment.

![]()

Dr. Lonky: If you were to rank vulvar pain syndromes according to their prevalence, what would the most common syndromes be?

Dr. Gunter: Given the misdiagnosis of many women, who are told they have chronic yeast infection, as I mentioned, it’s hard to know which vulvar pain syndromes are most prevalent. I suspect that lichen simplex chronicus is most common, followed by vulvodynia, with chronic yeast infection a distant third.

My experience reflects what Nyirjesy and colleagues4 found: 65% to 75% of women referred to my clinic with chronic yeast actually have lichen simplex chronicus or vulvodynia. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis is also a consideration; it’s becoming more common now that the use of systemic hormone replacement therapy is decreasing.

Dr. Lonky: What about subsets of vulvodynia? Which ones are most common?

Dr. Edwards: There is good evidence of marked overlap among subsets of vulvodynia. The vast majority of women who have vulvodynia experience primarily provoked vestibular pain, regardless of age. However, I find that almost all patients also report pain that extends beyond the vestibule at times, as well as occasional unprovoked pain.

The diagnosis requires the exclusion of other causes of vulvar pain, and the subset is identified by the location of pain (that is, is it strictly localized or generalized or even migratory?) and its provoked or unprovoked nature.

Localized clitoral pain and vulvar pain localized to one side of the vulva are extremely uncommon, but they do occur. And although I rarely encounter teenagers and prepubertal children who have vulvodynia, I do have patients in both age groups who have vulvodynia.

Dr. Lonky: Are there racial differences in the prevalence of vulvodynia?

Dr. Edwards: Although several good studies show that women of African descent and white patients are equally likely to experience vulvodynia, the vast majority (99%) of my patients who have vulvodynia are white. My patients of African descent consult me primarily for itching or discharge.

My local demographics prevent me from judging the likelihood of Asians having vulvodynia, and our Hispanic population has limited access to health care.

In general, I don’t think that demographics are useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia.

![]()

Dr. Lonky: Do your patients who have vulvodynia or another vulvar pain syndrome tend to have comorbidities? If so, is this information helpful in establishing the diagnosis and planning therapy?

Dr. Haefner: Women who have vulvodynia often have other medical problems as well. In my practice, when new patients who have vulvodynia complete their intake survey, they often report a history of headache, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, fibromyalgia,6 chronic fatigue syndrome, back pain, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder. These comorbidities are not particularly helpful in establishing the diagnosis of vulvodynia, but they are an important consideration when choosing therapy for the patient. Often, the medications chosen to treat one condition will also benefit another condition. However, it’s important to check for potential interactions between drugs before prescribing a new treatment.

Dr. Gunter: A significant number of women who have vulvodynia also have other chronic pain syndromes. For example, the incidence of bladder pain syndrome–interstitial cystitis is 68% to 82% among women who have vulvodynia, compared with a baseline rate among all women of 6% to 11%.7-10 The rate of irritable bowel syndrome is more than doubled among women who have vulvodynia, compared with the general population (27% versus 12%).8 Another common comorbidity, hypertonic somatic dysfunction of the pelvic floor, is identified in 10% to 90% of women who have chronic vulvar pain.8,11,12 These women also have a higher incidence of nongenital pain syndromes, such as fibromyalgia, migraine, and TMJ dysfunction, than the general population, as Dr. Haefner noted.8,12,13

Many studies have evaluated psychological and emotional contributions to chronic vulvar pain. Pain and depression are intimately related—the incidence of depression among all people who experience chronic pain ranges from 27% to 54%, compared with 5% to 17% among the general population.14-16 The relationship is complex because chronic illness in general is associated with depression. Nevertheless, several studies have noted an increase in anxiety, stress, and depression among women who have vulvodynia.17-19