User login

The Diagnosis: Acquired Lymphangioma Circumscriptum

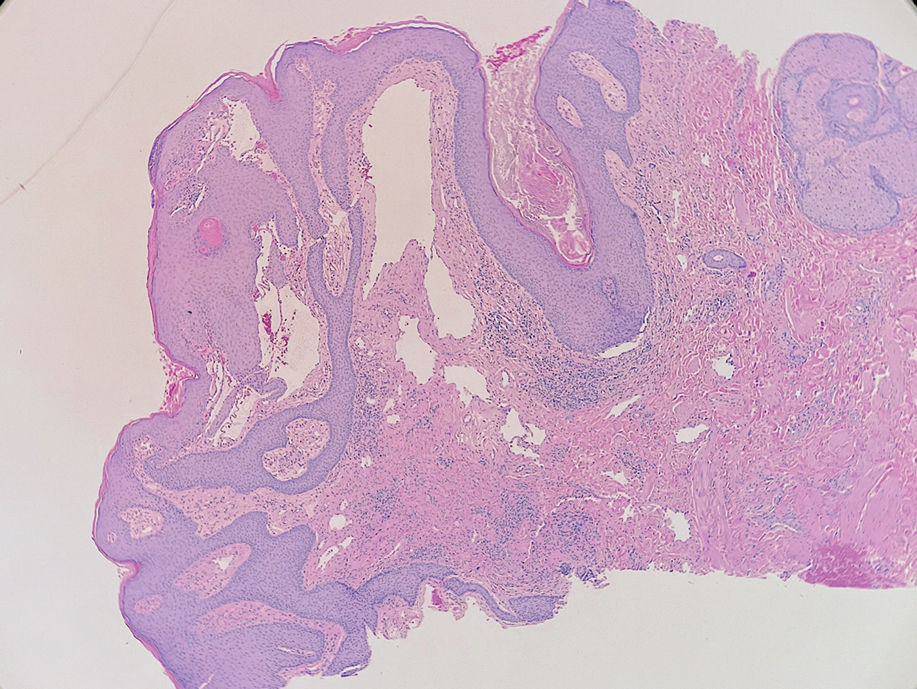

A skin biopsy of the plaque on the right labium majus showed a proliferation of well-formed, dilated lymphatic vessels lined by benign-appearing endothelial cells in the papillary dermis (Figure). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum (ALC) in the setting of severe hidradenitis suppurativa (HS).

Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum (also known as acquired lymphangiectasia or secondary lymphangioma1) is a rare skin finding resulting from chronic lymphatic obstruction that leads to dilated lymphatic vessels within the dermis.2,3 There also is a distinct congenital form of lymphangioma circumscriptum caused by lymphatic malformations present at birth.2,4 Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva is a rare phenomenon.3 Identified causes include radiation or surgery for carcinoma, solid gynecologic tumors, lymphadenectomy, Crohn disease, and tuberculosis and other infections, all of which can disrupt normal lymphatics to cause ALC.2-4 Hidradenitis suppurativa is not a widely recognized cause of ALC; however, this phenomenon is reported in the literature. A long-standing history of severe HS complicated by lymphedema seems to precede the development of ALC in the reported cases, as in our patient.5-7

Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva can appear in women of all ages as frog spawn or cobblestone papules or vesicles, sometimes with a hyperkeratotic or verrucous appearance.2,4 Associated symptoms include serous drainage, edema, pruritus, and discomfort. The lesions may become eroded, which can predispose patients to secondary infections.1,2 Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva can be difficult to diagnose, as the time interval between the initial cause and the appearance of skin findings can be years, leading to the misdiagnosis of ALC as other similar-appearing genital skin conditions such as squamous cell carcinoma or condyloma.4,8 When misidentified as an infection, diagnosis can lead to substantial distress, abstinence from sexual activity, and unnecessary and painful treatments.

Skin biopsy is helpful in distinguishing ALC from other differential diagnoses such as condylomata acuminata, squamous cell carcinoma, and condyloma lata. Histopathology in ALC is notable for dilated lymphatic vessels filled with hypocellular fluid and lined with endothelial cells in the superficial dermis; the epidermis can appear hyperplastic, hyperkeratotic, or eroded.3-5,9 These lymphatic vessels stain positively for CD31 and D2-40, markers for endothelial cells and lymphatic endothelium, respectively, and negative for CD34, a marker for vascular endothelium.3,4,9 Features suggestive of condylomata acuminata such as rounded parakeratosis, hypergranulosis, and vacuolated keratinocytes9 are not present. The giant condyloma of Buschke-Löwenstein, a clinical variant of verrucous squamous cell carcinoma, also can present as a warty ulcerated papule or plaque in the genital region, but the characteristic rounded eosinophilic keratinocytes pushing down into the dermis9 are not seen in ALC. Secondary syphilis is associated with condyloma lata, which are verrucous or fleshy-appearing papules often coalescing into plaques located in the anogenital region. Pathologic features of secondary syphilis include vacuolar interface dermatitis and acanthosis with long slender rete ridges.9 Squamous cell carcinoma, which can arise from inflammation associated with long-standing HS, must be ruled out, as it is associated with a high risk of mortality in patients with HS.10

It is noteworthy to recognize the various, often confusing nomenclature used to describe cutaneous lymphatic conditions. The terms acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum, secondary lymphangioma, and lymphangiectasia are used interchangeably to describe dilated lymphatic vessels in the skin.1 The term atypical vascular lesion refers to lymphectasias of the skin of the breast due to prior radiation therapy most often used in the treatment of breast carcinoma; clinically, these present as red-brown or flesh-colored papules or telangiectatic plaques on the breast.11,12 Lymphedema also may occur alongside atypical vascular lesions, as prior radiation or surgical lymph node dissection can predispose patients to impaired lymphatic drainage.13 The lymphatic histopathologic subtype of atypical vascular lesions may appear similar to ALC; however, the vascular subtype will demonstrate collections of capillary-sized vessels and extravasated erythrocytes.11,12 Unlike ALC, the benign nature of atypical vascular lesions has been questioned, as they may be associated with a small risk for progression to angiosarcoma.11-13 It also is important to distinguish ALC from lymphangiomatosis, a generalized lymphatic anomaly that is characterized by extensive lymphatic malformations involving numerous internal organs, including the lungs and gastrointestinal tract. This condition is associated with notable morbidity and mortality.13

Although the suffix of the term lymphangioma suggests a neoplastic process, ALC is not a neoplasm and can be managed expectantly in many cases.2,3,8 However, due to cosmetic appearance, pain, discomfort, and recurrent bacterial superinfections, many patients pursue treatment. Treatment options for ALC include sclerotherapy, electrocautery, radiofrequency or carbon dioxide laser ablation, and excision, though recurrence can arise.3-5,7,8 Our patient elected to manage her asymptomatic ALC expectantly.

- Verma SB. Lymphangiectasias of the skin: victims of confusing nomenclature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:566-569.

- Vlastos AT, Malpica A, Follen M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:946-954.

- Chang MB, Newman CC, Davis MD, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasia (lymphangioma circumscriptum) of the vulva: clinicopathologic study of 11 patients from a single institution and 67 from the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E482-E487.

- Stewart CJ, Chan T, Platten M. Acquired lymphangiectasia (‘lymphangioma circumscriptum’) of the vulva: a report of eight cases. Pathology. 2009;41:448-453.

- Sims SM, McLean FW, Davis JD, et al. Vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a report of 3 cases, 2 associated with vulvar carcinoma and 1 with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010; 14:234-237.

- Moosbrugger EA, Mutasim DF. Hidradenitis suppurativa complicated by severe lymphedema and lymphangiectasias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;6:1223-1224.

- Piernick DM 2nd, Mahmood SH, Daveluy S. Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the genitals in an individual with chronic hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;1:64-66.

- Horn LC, Kühndel K, Pawlowitsch T, et al. Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva mimicking genital warts. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;1:118-120.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Kohorst JJ, Shah KK, Hallemeier CL, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma in perineal, perianal, and gluteal hidradenitis suppurativa: experience in 12 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:519-526.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Ronen S, Ivan D, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Post-radiation vascular lesions of the breast. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:52-58.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Lymphangioma Circumscriptum

A skin biopsy of the plaque on the right labium majus showed a proliferation of well-formed, dilated lymphatic vessels lined by benign-appearing endothelial cells in the papillary dermis (Figure). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum (ALC) in the setting of severe hidradenitis suppurativa (HS).

Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum (also known as acquired lymphangiectasia or secondary lymphangioma1) is a rare skin finding resulting from chronic lymphatic obstruction that leads to dilated lymphatic vessels within the dermis.2,3 There also is a distinct congenital form of lymphangioma circumscriptum caused by lymphatic malformations present at birth.2,4 Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva is a rare phenomenon.3 Identified causes include radiation or surgery for carcinoma, solid gynecologic tumors, lymphadenectomy, Crohn disease, and tuberculosis and other infections, all of which can disrupt normal lymphatics to cause ALC.2-4 Hidradenitis suppurativa is not a widely recognized cause of ALC; however, this phenomenon is reported in the literature. A long-standing history of severe HS complicated by lymphedema seems to precede the development of ALC in the reported cases, as in our patient.5-7

Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva can appear in women of all ages as frog spawn or cobblestone papules or vesicles, sometimes with a hyperkeratotic or verrucous appearance.2,4 Associated symptoms include serous drainage, edema, pruritus, and discomfort. The lesions may become eroded, which can predispose patients to secondary infections.1,2 Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva can be difficult to diagnose, as the time interval between the initial cause and the appearance of skin findings can be years, leading to the misdiagnosis of ALC as other similar-appearing genital skin conditions such as squamous cell carcinoma or condyloma.4,8 When misidentified as an infection, diagnosis can lead to substantial distress, abstinence from sexual activity, and unnecessary and painful treatments.

Skin biopsy is helpful in distinguishing ALC from other differential diagnoses such as condylomata acuminata, squamous cell carcinoma, and condyloma lata. Histopathology in ALC is notable for dilated lymphatic vessels filled with hypocellular fluid and lined with endothelial cells in the superficial dermis; the epidermis can appear hyperplastic, hyperkeratotic, or eroded.3-5,9 These lymphatic vessels stain positively for CD31 and D2-40, markers for endothelial cells and lymphatic endothelium, respectively, and negative for CD34, a marker for vascular endothelium.3,4,9 Features suggestive of condylomata acuminata such as rounded parakeratosis, hypergranulosis, and vacuolated keratinocytes9 are not present. The giant condyloma of Buschke-Löwenstein, a clinical variant of verrucous squamous cell carcinoma, also can present as a warty ulcerated papule or plaque in the genital region, but the characteristic rounded eosinophilic keratinocytes pushing down into the dermis9 are not seen in ALC. Secondary syphilis is associated with condyloma lata, which are verrucous or fleshy-appearing papules often coalescing into plaques located in the anogenital region. Pathologic features of secondary syphilis include vacuolar interface dermatitis and acanthosis with long slender rete ridges.9 Squamous cell carcinoma, which can arise from inflammation associated with long-standing HS, must be ruled out, as it is associated with a high risk of mortality in patients with HS.10

It is noteworthy to recognize the various, often confusing nomenclature used to describe cutaneous lymphatic conditions. The terms acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum, secondary lymphangioma, and lymphangiectasia are used interchangeably to describe dilated lymphatic vessels in the skin.1 The term atypical vascular lesion refers to lymphectasias of the skin of the breast due to prior radiation therapy most often used in the treatment of breast carcinoma; clinically, these present as red-brown or flesh-colored papules or telangiectatic plaques on the breast.11,12 Lymphedema also may occur alongside atypical vascular lesions, as prior radiation or surgical lymph node dissection can predispose patients to impaired lymphatic drainage.13 The lymphatic histopathologic subtype of atypical vascular lesions may appear similar to ALC; however, the vascular subtype will demonstrate collections of capillary-sized vessels and extravasated erythrocytes.11,12 Unlike ALC, the benign nature of atypical vascular lesions has been questioned, as they may be associated with a small risk for progression to angiosarcoma.11-13 It also is important to distinguish ALC from lymphangiomatosis, a generalized lymphatic anomaly that is characterized by extensive lymphatic malformations involving numerous internal organs, including the lungs and gastrointestinal tract. This condition is associated with notable morbidity and mortality.13

Although the suffix of the term lymphangioma suggests a neoplastic process, ALC is not a neoplasm and can be managed expectantly in many cases.2,3,8 However, due to cosmetic appearance, pain, discomfort, and recurrent bacterial superinfections, many patients pursue treatment. Treatment options for ALC include sclerotherapy, electrocautery, radiofrequency or carbon dioxide laser ablation, and excision, though recurrence can arise.3-5,7,8 Our patient elected to manage her asymptomatic ALC expectantly.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Lymphangioma Circumscriptum

A skin biopsy of the plaque on the right labium majus showed a proliferation of well-formed, dilated lymphatic vessels lined by benign-appearing endothelial cells in the papillary dermis (Figure). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum (ALC) in the setting of severe hidradenitis suppurativa (HS).

Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum (also known as acquired lymphangiectasia or secondary lymphangioma1) is a rare skin finding resulting from chronic lymphatic obstruction that leads to dilated lymphatic vessels within the dermis.2,3 There also is a distinct congenital form of lymphangioma circumscriptum caused by lymphatic malformations present at birth.2,4 Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva is a rare phenomenon.3 Identified causes include radiation or surgery for carcinoma, solid gynecologic tumors, lymphadenectomy, Crohn disease, and tuberculosis and other infections, all of which can disrupt normal lymphatics to cause ALC.2-4 Hidradenitis suppurativa is not a widely recognized cause of ALC; however, this phenomenon is reported in the literature. A long-standing history of severe HS complicated by lymphedema seems to precede the development of ALC in the reported cases, as in our patient.5-7

Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva can appear in women of all ages as frog spawn or cobblestone papules or vesicles, sometimes with a hyperkeratotic or verrucous appearance.2,4 Associated symptoms include serous drainage, edema, pruritus, and discomfort. The lesions may become eroded, which can predispose patients to secondary infections.1,2 Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva can be difficult to diagnose, as the time interval between the initial cause and the appearance of skin findings can be years, leading to the misdiagnosis of ALC as other similar-appearing genital skin conditions such as squamous cell carcinoma or condyloma.4,8 When misidentified as an infection, diagnosis can lead to substantial distress, abstinence from sexual activity, and unnecessary and painful treatments.

Skin biopsy is helpful in distinguishing ALC from other differential diagnoses such as condylomata acuminata, squamous cell carcinoma, and condyloma lata. Histopathology in ALC is notable for dilated lymphatic vessels filled with hypocellular fluid and lined with endothelial cells in the superficial dermis; the epidermis can appear hyperplastic, hyperkeratotic, or eroded.3-5,9 These lymphatic vessels stain positively for CD31 and D2-40, markers for endothelial cells and lymphatic endothelium, respectively, and negative for CD34, a marker for vascular endothelium.3,4,9 Features suggestive of condylomata acuminata such as rounded parakeratosis, hypergranulosis, and vacuolated keratinocytes9 are not present. The giant condyloma of Buschke-Löwenstein, a clinical variant of verrucous squamous cell carcinoma, also can present as a warty ulcerated papule or plaque in the genital region, but the characteristic rounded eosinophilic keratinocytes pushing down into the dermis9 are not seen in ALC. Secondary syphilis is associated with condyloma lata, which are verrucous or fleshy-appearing papules often coalescing into plaques located in the anogenital region. Pathologic features of secondary syphilis include vacuolar interface dermatitis and acanthosis with long slender rete ridges.9 Squamous cell carcinoma, which can arise from inflammation associated with long-standing HS, must be ruled out, as it is associated with a high risk of mortality in patients with HS.10

It is noteworthy to recognize the various, often confusing nomenclature used to describe cutaneous lymphatic conditions. The terms acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum, secondary lymphangioma, and lymphangiectasia are used interchangeably to describe dilated lymphatic vessels in the skin.1 The term atypical vascular lesion refers to lymphectasias of the skin of the breast due to prior radiation therapy most often used in the treatment of breast carcinoma; clinically, these present as red-brown or flesh-colored papules or telangiectatic plaques on the breast.11,12 Lymphedema also may occur alongside atypical vascular lesions, as prior radiation or surgical lymph node dissection can predispose patients to impaired lymphatic drainage.13 The lymphatic histopathologic subtype of atypical vascular lesions may appear similar to ALC; however, the vascular subtype will demonstrate collections of capillary-sized vessels and extravasated erythrocytes.11,12 Unlike ALC, the benign nature of atypical vascular lesions has been questioned, as they may be associated with a small risk for progression to angiosarcoma.11-13 It also is important to distinguish ALC from lymphangiomatosis, a generalized lymphatic anomaly that is characterized by extensive lymphatic malformations involving numerous internal organs, including the lungs and gastrointestinal tract. This condition is associated with notable morbidity and mortality.13

Although the suffix of the term lymphangioma suggests a neoplastic process, ALC is not a neoplasm and can be managed expectantly in many cases.2,3,8 However, due to cosmetic appearance, pain, discomfort, and recurrent bacterial superinfections, many patients pursue treatment. Treatment options for ALC include sclerotherapy, electrocautery, radiofrequency or carbon dioxide laser ablation, and excision, though recurrence can arise.3-5,7,8 Our patient elected to manage her asymptomatic ALC expectantly.

- Verma SB. Lymphangiectasias of the skin: victims of confusing nomenclature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:566-569.

- Vlastos AT, Malpica A, Follen M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:946-954.

- Chang MB, Newman CC, Davis MD, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasia (lymphangioma circumscriptum) of the vulva: clinicopathologic study of 11 patients from a single institution and 67 from the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E482-E487.

- Stewart CJ, Chan T, Platten M. Acquired lymphangiectasia (‘lymphangioma circumscriptum’) of the vulva: a report of eight cases. Pathology. 2009;41:448-453.

- Sims SM, McLean FW, Davis JD, et al. Vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a report of 3 cases, 2 associated with vulvar carcinoma and 1 with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010; 14:234-237.

- Moosbrugger EA, Mutasim DF. Hidradenitis suppurativa complicated by severe lymphedema and lymphangiectasias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;6:1223-1224.

- Piernick DM 2nd, Mahmood SH, Daveluy S. Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the genitals in an individual with chronic hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;1:64-66.

- Horn LC, Kühndel K, Pawlowitsch T, et al. Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva mimicking genital warts. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;1:118-120.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Kohorst JJ, Shah KK, Hallemeier CL, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma in perineal, perianal, and gluteal hidradenitis suppurativa: experience in 12 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:519-526.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Ronen S, Ivan D, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Post-radiation vascular lesions of the breast. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:52-58.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Verma SB. Lymphangiectasias of the skin: victims of confusing nomenclature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:566-569.

- Vlastos AT, Malpica A, Follen M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:946-954.

- Chang MB, Newman CC, Davis MD, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasia (lymphangioma circumscriptum) of the vulva: clinicopathologic study of 11 patients from a single institution and 67 from the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E482-E487.

- Stewart CJ, Chan T, Platten M. Acquired lymphangiectasia (‘lymphangioma circumscriptum’) of the vulva: a report of eight cases. Pathology. 2009;41:448-453.

- Sims SM, McLean FW, Davis JD, et al. Vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a report of 3 cases, 2 associated with vulvar carcinoma and 1 with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010; 14:234-237.

- Moosbrugger EA, Mutasim DF. Hidradenitis suppurativa complicated by severe lymphedema and lymphangiectasias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;6:1223-1224.

- Piernick DM 2nd, Mahmood SH, Daveluy S. Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the genitals in an individual with chronic hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;1:64-66.

- Horn LC, Kühndel K, Pawlowitsch T, et al. Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva mimicking genital warts. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;1:118-120.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Kohorst JJ, Shah KK, Hallemeier CL, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma in perineal, perianal, and gluteal hidradenitis suppurativa: experience in 12 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:519-526.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Ronen S, Ivan D, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Post-radiation vascular lesions of the breast. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:52-58.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

A 38-year-old woman with long-standing severe hidradenitis suppurativa presented to our dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic, slowly enlarging growth on the right labium majus of 2 years’ duration. She also had severe persistent drainage from nodules and sinus tracts involving the abdominal pannus, inguinal folds, vulva, perineum, buttocks, and upper thighs. After treatment failure with oral antibiotics and adalimumab, her regimen included infliximab-dyyb, chronic systemic steroids, spironolactone, topical clindamycin, and benzoyl peroxide, with plans for eventual surgical intervention. Physical examination revealed the patient had numerous pink papules coalescing into a plaque on the right labium majus. She also had innumerable papulonodules, sinus tracts, and indurated scars in the inguinal folds, genitalia, and perineal region from severe hidradenitis suppurativa.