User login

To the Editor: In their paper on colorectal cancer screening, Mankaney and colleagues noted the increasing rates of colorectal cancer in young adults in the United States.1 Recent epidemiologic data demonstrate an increasing incidence of the disease in people ages 40 through 49 since the mid-1990s.2 Even though screening starting at age 45 is not uniformly accepted,1 there is evidence supporting earlier screening.

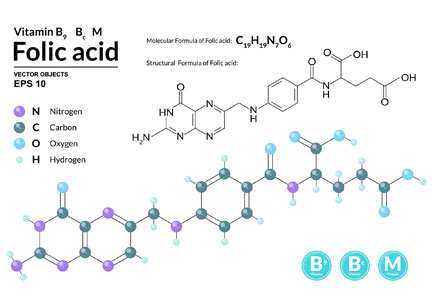

During the mid-1990s, the US government mandated that all enriched flour and uncooked cereal grains were to be fortified with folic acid in order to prevent births complicated by neural tube defects.3 Subsequently, there was a 2-fold increase in plasma folate concentrations and, disturbingly, a temporally associated significant increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer.3

Notably, a US trial4 testing the efficacy of folic acid 1 mg taken daily for 6 years to prevent colorectal adenomas in those with a history of colorectal adenomas failed to show a reduction in adenoma risk. Instead, participants randomized to folic acid exhibited a significantly increased risk of an advanced adenoma. Another trial,5 conducted in the Netherlands, where there is no mandatory folic acid fortification, investigated folic acid 400 µg and vitamin B12 500 µg daily over 2 to 3 years for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures. The group randomized to the vitamins had a nearly 2-fold increase in the risk of colorectal cancer.

Folic acid can be a double-edged sword.3,5 Although folic acid intake may protect against carcinogenesis through increased genetic stability, if precancerous or neoplastic cells are present, excess folic acid may promote cancer by increasing DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. Cancer cells have folic acid receptors.

Since screening colonoscopy is typically done in individuals over 50, advanced adenomas from folic acid exposure in people younger than 50 likely go undiagnosed. Therefore, colorectal cancer screening should start at a younger age in countries where folic acid fortification is mandatory.

- Mankaney G, Sutton RA, Burke CA. Colorectal cancer screening: choosing the right test. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(6):385–392. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.17125

- Meester RGS, Mannalithara A, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Ladabaum U. Trends in incidence and stage at diagnosis of colorectal cancer in adults aged 40 through 49 years, 1975–2015. JAMA 2019; 321(19):1933–1934. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3076

- Mason JB, Dickstein A, Jacques PF, et al. A temporal association between folic acid fortification and an increase in colorectal cancer rates may be illuminating important biological principles: a hypothesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16(7):1325–1329. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0329

- Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al; POlyp Prevention Study Group. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2007; 297(21):2351–2359. doi:10.1001/jama.297.21.2351

- Oliai Araghi S, Kiefte-de Jong JC, van Dijk SC, et al. Folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation and the risk of cancer: long-term follow-up of the B vitamins for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures (B-PROOF) Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(2):275–282. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1198

To the Editor: In their paper on colorectal cancer screening, Mankaney and colleagues noted the increasing rates of colorectal cancer in young adults in the United States.1 Recent epidemiologic data demonstrate an increasing incidence of the disease in people ages 40 through 49 since the mid-1990s.2 Even though screening starting at age 45 is not uniformly accepted,1 there is evidence supporting earlier screening.

During the mid-1990s, the US government mandated that all enriched flour and uncooked cereal grains were to be fortified with folic acid in order to prevent births complicated by neural tube defects.3 Subsequently, there was a 2-fold increase in plasma folate concentrations and, disturbingly, a temporally associated significant increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer.3

Notably, a US trial4 testing the efficacy of folic acid 1 mg taken daily for 6 years to prevent colorectal adenomas in those with a history of colorectal adenomas failed to show a reduction in adenoma risk. Instead, participants randomized to folic acid exhibited a significantly increased risk of an advanced adenoma. Another trial,5 conducted in the Netherlands, where there is no mandatory folic acid fortification, investigated folic acid 400 µg and vitamin B12 500 µg daily over 2 to 3 years for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures. The group randomized to the vitamins had a nearly 2-fold increase in the risk of colorectal cancer.

Folic acid can be a double-edged sword.3,5 Although folic acid intake may protect against carcinogenesis through increased genetic stability, if precancerous or neoplastic cells are present, excess folic acid may promote cancer by increasing DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. Cancer cells have folic acid receptors.

Since screening colonoscopy is typically done in individuals over 50, advanced adenomas from folic acid exposure in people younger than 50 likely go undiagnosed. Therefore, colorectal cancer screening should start at a younger age in countries where folic acid fortification is mandatory.

To the Editor: In their paper on colorectal cancer screening, Mankaney and colleagues noted the increasing rates of colorectal cancer in young adults in the United States.1 Recent epidemiologic data demonstrate an increasing incidence of the disease in people ages 40 through 49 since the mid-1990s.2 Even though screening starting at age 45 is not uniformly accepted,1 there is evidence supporting earlier screening.

During the mid-1990s, the US government mandated that all enriched flour and uncooked cereal grains were to be fortified with folic acid in order to prevent births complicated by neural tube defects.3 Subsequently, there was a 2-fold increase in plasma folate concentrations and, disturbingly, a temporally associated significant increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer.3

Notably, a US trial4 testing the efficacy of folic acid 1 mg taken daily for 6 years to prevent colorectal adenomas in those with a history of colorectal adenomas failed to show a reduction in adenoma risk. Instead, participants randomized to folic acid exhibited a significantly increased risk of an advanced adenoma. Another trial,5 conducted in the Netherlands, where there is no mandatory folic acid fortification, investigated folic acid 400 µg and vitamin B12 500 µg daily over 2 to 3 years for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures. The group randomized to the vitamins had a nearly 2-fold increase in the risk of colorectal cancer.

Folic acid can be a double-edged sword.3,5 Although folic acid intake may protect against carcinogenesis through increased genetic stability, if precancerous or neoplastic cells are present, excess folic acid may promote cancer by increasing DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. Cancer cells have folic acid receptors.

Since screening colonoscopy is typically done in individuals over 50, advanced adenomas from folic acid exposure in people younger than 50 likely go undiagnosed. Therefore, colorectal cancer screening should start at a younger age in countries where folic acid fortification is mandatory.

- Mankaney G, Sutton RA, Burke CA. Colorectal cancer screening: choosing the right test. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(6):385–392. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.17125

- Meester RGS, Mannalithara A, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Ladabaum U. Trends in incidence and stage at diagnosis of colorectal cancer in adults aged 40 through 49 years, 1975–2015. JAMA 2019; 321(19):1933–1934. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3076

- Mason JB, Dickstein A, Jacques PF, et al. A temporal association between folic acid fortification and an increase in colorectal cancer rates may be illuminating important biological principles: a hypothesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16(7):1325–1329. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0329

- Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al; POlyp Prevention Study Group. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2007; 297(21):2351–2359. doi:10.1001/jama.297.21.2351

- Oliai Araghi S, Kiefte-de Jong JC, van Dijk SC, et al. Folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation and the risk of cancer: long-term follow-up of the B vitamins for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures (B-PROOF) Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(2):275–282. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1198

- Mankaney G, Sutton RA, Burke CA. Colorectal cancer screening: choosing the right test. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(6):385–392. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.17125

- Meester RGS, Mannalithara A, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Ladabaum U. Trends in incidence and stage at diagnosis of colorectal cancer in adults aged 40 through 49 years, 1975–2015. JAMA 2019; 321(19):1933–1934. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3076

- Mason JB, Dickstein A, Jacques PF, et al. A temporal association between folic acid fortification and an increase in colorectal cancer rates may be illuminating important biological principles: a hypothesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16(7):1325–1329. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0329

- Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al; POlyp Prevention Study Group. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2007; 297(21):2351–2359. doi:10.1001/jama.297.21.2351

- Oliai Araghi S, Kiefte-de Jong JC, van Dijk SC, et al. Folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation and the risk of cancer: long-term follow-up of the B vitamins for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures (B-PROOF) Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(2):275–282. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1198