User login

Colorectal cancer screening: Folic acid supplementation alters the equation

To the Editor: In their paper on colorectal cancer screening, Mankaney and colleagues noted the increasing rates of colorectal cancer in young adults in the United States.1 Recent epidemiologic data demonstrate an increasing incidence of the disease in people ages 40 through 49 since the mid-1990s.2 Even though screening starting at age 45 is not uniformly accepted,1 there is evidence supporting earlier screening.

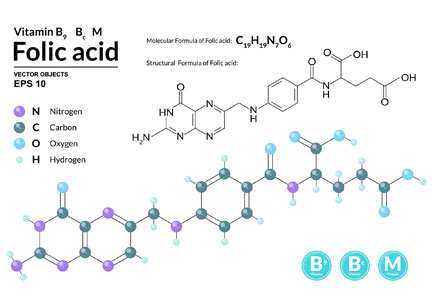

During the mid-1990s, the US government mandated that all enriched flour and uncooked cereal grains were to be fortified with folic acid in order to prevent births complicated by neural tube defects.3 Subsequently, there was a 2-fold increase in plasma folate concentrations and, disturbingly, a temporally associated significant increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer.3

Notably, a US trial4 testing the efficacy of folic acid 1 mg taken daily for 6 years to prevent colorectal adenomas in those with a history of colorectal adenomas failed to show a reduction in adenoma risk. Instead, participants randomized to folic acid exhibited a significantly increased risk of an advanced adenoma. Another trial,5 conducted in the Netherlands, where there is no mandatory folic acid fortification, investigated folic acid 400 µg and vitamin B12 500 µg daily over 2 to 3 years for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures. The group randomized to the vitamins had a nearly 2-fold increase in the risk of colorectal cancer.

Folic acid can be a double-edged sword.3,5 Although folic acid intake may protect against carcinogenesis through increased genetic stability, if precancerous or neoplastic cells are present, excess folic acid may promote cancer by increasing DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. Cancer cells have folic acid receptors.

Since screening colonoscopy is typically done in individuals over 50, advanced adenomas from folic acid exposure in people younger than 50 likely go undiagnosed. Therefore, colorectal cancer screening should start at a younger age in countries where folic acid fortification is mandatory.

- Mankaney G, Sutton RA, Burke CA. Colorectal cancer screening: choosing the right test. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(6):385–392. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.17125

- Meester RGS, Mannalithara A, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Ladabaum U. Trends in incidence and stage at diagnosis of colorectal cancer in adults aged 40 through 49 years, 1975–2015. JAMA 2019; 321(19):1933–1934. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3076

- Mason JB, Dickstein A, Jacques PF, et al. A temporal association between folic acid fortification and an increase in colorectal cancer rates may be illuminating important biological principles: a hypothesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16(7):1325–1329. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0329

- Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al; POlyp Prevention Study Group. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2007; 297(21):2351–2359. doi:10.1001/jama.297.21.2351

- Oliai Araghi S, Kiefte-de Jong JC, van Dijk SC, et al. Folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation and the risk of cancer: long-term follow-up of the B vitamins for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures (B-PROOF) Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(2):275–282. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1198

To the Editor: In their paper on colorectal cancer screening, Mankaney and colleagues noted the increasing rates of colorectal cancer in young adults in the United States.1 Recent epidemiologic data demonstrate an increasing incidence of the disease in people ages 40 through 49 since the mid-1990s.2 Even though screening starting at age 45 is not uniformly accepted,1 there is evidence supporting earlier screening.

During the mid-1990s, the US government mandated that all enriched flour and uncooked cereal grains were to be fortified with folic acid in order to prevent births complicated by neural tube defects.3 Subsequently, there was a 2-fold increase in plasma folate concentrations and, disturbingly, a temporally associated significant increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer.3

Notably, a US trial4 testing the efficacy of folic acid 1 mg taken daily for 6 years to prevent colorectal adenomas in those with a history of colorectal adenomas failed to show a reduction in adenoma risk. Instead, participants randomized to folic acid exhibited a significantly increased risk of an advanced adenoma. Another trial,5 conducted in the Netherlands, where there is no mandatory folic acid fortification, investigated folic acid 400 µg and vitamin B12 500 µg daily over 2 to 3 years for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures. The group randomized to the vitamins had a nearly 2-fold increase in the risk of colorectal cancer.

Folic acid can be a double-edged sword.3,5 Although folic acid intake may protect against carcinogenesis through increased genetic stability, if precancerous or neoplastic cells are present, excess folic acid may promote cancer by increasing DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. Cancer cells have folic acid receptors.

Since screening colonoscopy is typically done in individuals over 50, advanced adenomas from folic acid exposure in people younger than 50 likely go undiagnosed. Therefore, colorectal cancer screening should start at a younger age in countries where folic acid fortification is mandatory.

To the Editor: In their paper on colorectal cancer screening, Mankaney and colleagues noted the increasing rates of colorectal cancer in young adults in the United States.1 Recent epidemiologic data demonstrate an increasing incidence of the disease in people ages 40 through 49 since the mid-1990s.2 Even though screening starting at age 45 is not uniformly accepted,1 there is evidence supporting earlier screening.

During the mid-1990s, the US government mandated that all enriched flour and uncooked cereal grains were to be fortified with folic acid in order to prevent births complicated by neural tube defects.3 Subsequently, there was a 2-fold increase in plasma folate concentrations and, disturbingly, a temporally associated significant increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer.3

Notably, a US trial4 testing the efficacy of folic acid 1 mg taken daily for 6 years to prevent colorectal adenomas in those with a history of colorectal adenomas failed to show a reduction in adenoma risk. Instead, participants randomized to folic acid exhibited a significantly increased risk of an advanced adenoma. Another trial,5 conducted in the Netherlands, where there is no mandatory folic acid fortification, investigated folic acid 400 µg and vitamin B12 500 µg daily over 2 to 3 years for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures. The group randomized to the vitamins had a nearly 2-fold increase in the risk of colorectal cancer.

Folic acid can be a double-edged sword.3,5 Although folic acid intake may protect against carcinogenesis through increased genetic stability, if precancerous or neoplastic cells are present, excess folic acid may promote cancer by increasing DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. Cancer cells have folic acid receptors.

Since screening colonoscopy is typically done in individuals over 50, advanced adenomas from folic acid exposure in people younger than 50 likely go undiagnosed. Therefore, colorectal cancer screening should start at a younger age in countries where folic acid fortification is mandatory.

- Mankaney G, Sutton RA, Burke CA. Colorectal cancer screening: choosing the right test. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(6):385–392. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.17125

- Meester RGS, Mannalithara A, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Ladabaum U. Trends in incidence and stage at diagnosis of colorectal cancer in adults aged 40 through 49 years, 1975–2015. JAMA 2019; 321(19):1933–1934. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3076

- Mason JB, Dickstein A, Jacques PF, et al. A temporal association between folic acid fortification and an increase in colorectal cancer rates may be illuminating important biological principles: a hypothesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16(7):1325–1329. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0329

- Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al; POlyp Prevention Study Group. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2007; 297(21):2351–2359. doi:10.1001/jama.297.21.2351

- Oliai Araghi S, Kiefte-de Jong JC, van Dijk SC, et al. Folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation and the risk of cancer: long-term follow-up of the B vitamins for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures (B-PROOF) Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(2):275–282. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1198

- Mankaney G, Sutton RA, Burke CA. Colorectal cancer screening: choosing the right test. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(6):385–392. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.17125

- Meester RGS, Mannalithara A, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Ladabaum U. Trends in incidence and stage at diagnosis of colorectal cancer in adults aged 40 through 49 years, 1975–2015. JAMA 2019; 321(19):1933–1934. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3076

- Mason JB, Dickstein A, Jacques PF, et al. A temporal association between folic acid fortification and an increase in colorectal cancer rates may be illuminating important biological principles: a hypothesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16(7):1325–1329. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0329

- Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al; POlyp Prevention Study Group. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2007; 297(21):2351–2359. doi:10.1001/jama.297.21.2351

- Oliai Araghi S, Kiefte-de Jong JC, van Dijk SC, et al. Folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation and the risk of cancer: long-term follow-up of the B vitamins for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures (B-PROOF) Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(2):275–282. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1198

Aortic aneurysm: Fluoroquinolones, genetic counseling

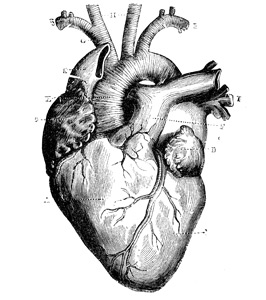

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Cikach et al on thoracic aortic aneurysm.1 For medical management of this condition, the authors emphasized controlling blood pressure and heart rate and also avoiding isometric exercises and heavy lifting. In addition to their recommendations, we believe there is plausible evidence to advise caution if fluoroquinolone antibiotics are used in this setting.

Three large population-based studies, from Canada,2 Taiwan,3 and Sweden,4 collectively demonstrated a significant 2-fold increase in the incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection presenting within 60 days of fluoroquinolone use compared with other antibiotic exposure. Moreover, a longer duration of fluoroquinolone use was associated with a significantly higher incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection.3

Mechanistically, fluoroquinolones have been shown to up-regulate production of several matrix metalloproteinases, including metalloproteinase 2, leading to degradation of type I collagen.2,5 Type I and type III are the dominant collagens in the aortic wall, and collagen degradation is implicated in aortic aneurysm formation and expansion.

Fluoroquinolones are widely prescribed in both outpatient and inpatient settings and are sometimes used for long durations in the geriatric population.2 It is possible that these drugs have a propensity to increase aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection in older patients who already have aortic aneurysm. Accordingly, this might make the risk-benefit ratio unfavorable for using these drugs in these situations, and other antibiotics should be used, if indicated.

Furthermore, if fluoroquinolones are used in patients with aortic aneurysm, perhaps imaging studies of the aneurysm should be done more frequently than once a year to detect accelerated aneurysm growth. Finally, physicians should be aware of the possibility of increased aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection with fluoroquinolone use.

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- Daneman N, Lu H, Redelmeier DA. Fluoroquinolones and collagen associated severe adverse events: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2015; 5:e010077. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010077

- Lee C-C, Lee MG, Chen Y-S, et al. Risk of aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm in patients taking oral fluoroquinolone. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1839–1847. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5389

- Pasternak B, Inghammar M, Svanström H. Fluoroquinolone use and risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open 2018; 360:k678. doi:10.1136/bmj.k678

- Tsai W-C, Hsu C-C, Chen CPC, et al. Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J Orthop Res 2011; 29(1):67–73. doi:10.1002/jor.21196

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Cikach et al on thoracic aortic aneurysm.1 For medical management of this condition, the authors emphasized controlling blood pressure and heart rate and also avoiding isometric exercises and heavy lifting. In addition to their recommendations, we believe there is plausible evidence to advise caution if fluoroquinolone antibiotics are used in this setting.

Three large population-based studies, from Canada,2 Taiwan,3 and Sweden,4 collectively demonstrated a significant 2-fold increase in the incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection presenting within 60 days of fluoroquinolone use compared with other antibiotic exposure. Moreover, a longer duration of fluoroquinolone use was associated with a significantly higher incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection.3

Mechanistically, fluoroquinolones have been shown to up-regulate production of several matrix metalloproteinases, including metalloproteinase 2, leading to degradation of type I collagen.2,5 Type I and type III are the dominant collagens in the aortic wall, and collagen degradation is implicated in aortic aneurysm formation and expansion.

Fluoroquinolones are widely prescribed in both outpatient and inpatient settings and are sometimes used for long durations in the geriatric population.2 It is possible that these drugs have a propensity to increase aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection in older patients who already have aortic aneurysm. Accordingly, this might make the risk-benefit ratio unfavorable for using these drugs in these situations, and other antibiotics should be used, if indicated.

Furthermore, if fluoroquinolones are used in patients with aortic aneurysm, perhaps imaging studies of the aneurysm should be done more frequently than once a year to detect accelerated aneurysm growth. Finally, physicians should be aware of the possibility of increased aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection with fluoroquinolone use.

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Cikach et al on thoracic aortic aneurysm.1 For medical management of this condition, the authors emphasized controlling blood pressure and heart rate and also avoiding isometric exercises and heavy lifting. In addition to their recommendations, we believe there is plausible evidence to advise caution if fluoroquinolone antibiotics are used in this setting.

Three large population-based studies, from Canada,2 Taiwan,3 and Sweden,4 collectively demonstrated a significant 2-fold increase in the incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection presenting within 60 days of fluoroquinolone use compared with other antibiotic exposure. Moreover, a longer duration of fluoroquinolone use was associated with a significantly higher incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection.3

Mechanistically, fluoroquinolones have been shown to up-regulate production of several matrix metalloproteinases, including metalloproteinase 2, leading to degradation of type I collagen.2,5 Type I and type III are the dominant collagens in the aortic wall, and collagen degradation is implicated in aortic aneurysm formation and expansion.

Fluoroquinolones are widely prescribed in both outpatient and inpatient settings and are sometimes used for long durations in the geriatric population.2 It is possible that these drugs have a propensity to increase aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection in older patients who already have aortic aneurysm. Accordingly, this might make the risk-benefit ratio unfavorable for using these drugs in these situations, and other antibiotics should be used, if indicated.

Furthermore, if fluoroquinolones are used in patients with aortic aneurysm, perhaps imaging studies of the aneurysm should be done more frequently than once a year to detect accelerated aneurysm growth. Finally, physicians should be aware of the possibility of increased aortic aneurysm expansion and dissection with fluoroquinolone use.

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- Daneman N, Lu H, Redelmeier DA. Fluoroquinolones and collagen associated severe adverse events: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2015; 5:e010077. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010077

- Lee C-C, Lee MG, Chen Y-S, et al. Risk of aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm in patients taking oral fluoroquinolone. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1839–1847. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5389

- Pasternak B, Inghammar M, Svanström H. Fluoroquinolone use and risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open 2018; 360:k678. doi:10.1136/bmj.k678

- Tsai W-C, Hsu C-C, Chen CPC, et al. Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J Orthop Res 2011; 29(1):67–73. doi:10.1002/jor.21196

- Cikach F, Desai MY, Roselli EE, Kalahasti V. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: how to counsel, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(6):481–492. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17039

- Daneman N, Lu H, Redelmeier DA. Fluoroquinolones and collagen associated severe adverse events: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2015; 5:e010077. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010077

- Lee C-C, Lee MG, Chen Y-S, et al. Risk of aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm in patients taking oral fluoroquinolone. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1839–1847. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5389

- Pasternak B, Inghammar M, Svanström H. Fluoroquinolone use and risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open 2018; 360:k678. doi:10.1136/bmj.k678

- Tsai W-C, Hsu C-C, Chen CPC, et al. Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J Orthop Res 2011; 29(1):67–73. doi:10.1002/jor.21196

Menopause, vitamin D, and oral health

To the Editor: Buencamino and colleagues1 reviewed the association between menopause and periodontal disease. However, they did not mention the role of vitamin D status in this setting.

Vitamin D status is usually divided into three categories based on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels: “deficient” (≤ 15 ng/mL), “insufficient” (15.1–29.9 ng/mL), and “sufficient” (≥ 30 ng/mL). Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels have been decreasing significantly for more than a decade, and as a result, a majority of the US population has a vitamin D insufficiency.

In the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), a large US population survey, a low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration was independently associated with periodontal disease.2 In particular, it was significantly associated with loss of alveolar attachment in persons older than 50 years of both sexes, independent of race or ethnicity; women in the highest 25-hydroxyvitamin D quintile had, on average, 0.26 mm (95% confidence interval 0.09–0.43 mm) less mean attachment loss than did women in the lowest quintile. Furthermore, in a randomized trial, supplementation with vitamin D (700 IU/day) plus calcium (500 mg/day) has been shown to significantly reduce tooth loss in older persons over a 3-year treatment period.3

Osteoporosis and periodontal disease share several risk factors, and it might be speculated that these pathologic conditions are biologically intertwined.4 The decreased bone mineral density of osteoporosis can lead to an altered trabecular pattern and more rapid alveolar bone resorption, thus predisposing to periodontal disease. On the other hand, periodontal infections can increase the systemic release of inflammatory cytokines, which accelerate systemic bone resorption. Indeed, vitamin D deficiency has been associated with a cytokine profile that favors greater inflammation (eg, higher levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin 6, and lower levels of interleukin 10), and vitamin D supplementation decreases circulating inflammatory markers.5 This might break the vicious circle of osteoporosis, periodontal disease development, and further systemic bone resorption.

Therefore, we suggest that menopausal women should maintain an adequate vitamin D status in order to prevent and treat osteoporosis-associated periodontal disease.

- Buencamino MC, Palomo L, Thacker HL. How menopause affects oral health, and what we can do about it. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:467–475.

- Dietrich T, Joshipura KJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Association between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and periodontal disease in the US population. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 80:108–113.

- Krall EA, Wehler C, Garcia RI, Harris SS, Dawson-Hughes B. Calcium and vitamin D supplements reduce tooth loss in the elderly. Am J Med 2001; 111:452–456.

- Amano Y, Komiyama K, Makishima M. Vitamin D and periodontal disease. J Oral Sci 2009; 51:11–20.

- Timms PM, Mannan N, Hitman GA, et al. Circulating MMP9, vitamin D and variation in the TIMP-1 response with VDR genotype: mechanisms for inflammatory damage in chronic disorders? QJM 2002; 95:787–796.

To the Editor: Buencamino and colleagues1 reviewed the association between menopause and periodontal disease. However, they did not mention the role of vitamin D status in this setting.

Vitamin D status is usually divided into three categories based on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels: “deficient” (≤ 15 ng/mL), “insufficient” (15.1–29.9 ng/mL), and “sufficient” (≥ 30 ng/mL). Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels have been decreasing significantly for more than a decade, and as a result, a majority of the US population has a vitamin D insufficiency.

In the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), a large US population survey, a low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration was independently associated with periodontal disease.2 In particular, it was significantly associated with loss of alveolar attachment in persons older than 50 years of both sexes, independent of race or ethnicity; women in the highest 25-hydroxyvitamin D quintile had, on average, 0.26 mm (95% confidence interval 0.09–0.43 mm) less mean attachment loss than did women in the lowest quintile. Furthermore, in a randomized trial, supplementation with vitamin D (700 IU/day) plus calcium (500 mg/day) has been shown to significantly reduce tooth loss in older persons over a 3-year treatment period.3

Osteoporosis and periodontal disease share several risk factors, and it might be speculated that these pathologic conditions are biologically intertwined.4 The decreased bone mineral density of osteoporosis can lead to an altered trabecular pattern and more rapid alveolar bone resorption, thus predisposing to periodontal disease. On the other hand, periodontal infections can increase the systemic release of inflammatory cytokines, which accelerate systemic bone resorption. Indeed, vitamin D deficiency has been associated with a cytokine profile that favors greater inflammation (eg, higher levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin 6, and lower levels of interleukin 10), and vitamin D supplementation decreases circulating inflammatory markers.5 This might break the vicious circle of osteoporosis, periodontal disease development, and further systemic bone resorption.

Therefore, we suggest that menopausal women should maintain an adequate vitamin D status in order to prevent and treat osteoporosis-associated periodontal disease.

To the Editor: Buencamino and colleagues1 reviewed the association between menopause and periodontal disease. However, they did not mention the role of vitamin D status in this setting.

Vitamin D status is usually divided into three categories based on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels: “deficient” (≤ 15 ng/mL), “insufficient” (15.1–29.9 ng/mL), and “sufficient” (≥ 30 ng/mL). Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels have been decreasing significantly for more than a decade, and as a result, a majority of the US population has a vitamin D insufficiency.

In the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), a large US population survey, a low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration was independently associated with periodontal disease.2 In particular, it was significantly associated with loss of alveolar attachment in persons older than 50 years of both sexes, independent of race or ethnicity; women in the highest 25-hydroxyvitamin D quintile had, on average, 0.26 mm (95% confidence interval 0.09–0.43 mm) less mean attachment loss than did women in the lowest quintile. Furthermore, in a randomized trial, supplementation with vitamin D (700 IU/day) plus calcium (500 mg/day) has been shown to significantly reduce tooth loss in older persons over a 3-year treatment period.3

Osteoporosis and periodontal disease share several risk factors, and it might be speculated that these pathologic conditions are biologically intertwined.4 The decreased bone mineral density of osteoporosis can lead to an altered trabecular pattern and more rapid alveolar bone resorption, thus predisposing to periodontal disease. On the other hand, periodontal infections can increase the systemic release of inflammatory cytokines, which accelerate systemic bone resorption. Indeed, vitamin D deficiency has been associated with a cytokine profile that favors greater inflammation (eg, higher levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin 6, and lower levels of interleukin 10), and vitamin D supplementation decreases circulating inflammatory markers.5 This might break the vicious circle of osteoporosis, periodontal disease development, and further systemic bone resorption.

Therefore, we suggest that menopausal women should maintain an adequate vitamin D status in order to prevent and treat osteoporosis-associated periodontal disease.

- Buencamino MC, Palomo L, Thacker HL. How menopause affects oral health, and what we can do about it. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:467–475.

- Dietrich T, Joshipura KJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Association between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and periodontal disease in the US population. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 80:108–113.

- Krall EA, Wehler C, Garcia RI, Harris SS, Dawson-Hughes B. Calcium and vitamin D supplements reduce tooth loss in the elderly. Am J Med 2001; 111:452–456.

- Amano Y, Komiyama K, Makishima M. Vitamin D and periodontal disease. J Oral Sci 2009; 51:11–20.

- Timms PM, Mannan N, Hitman GA, et al. Circulating MMP9, vitamin D and variation in the TIMP-1 response with VDR genotype: mechanisms for inflammatory damage in chronic disorders? QJM 2002; 95:787–796.

- Buencamino MC, Palomo L, Thacker HL. How menopause affects oral health, and what we can do about it. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:467–475.

- Dietrich T, Joshipura KJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Association between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and periodontal disease in the US population. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 80:108–113.

- Krall EA, Wehler C, Garcia RI, Harris SS, Dawson-Hughes B. Calcium and vitamin D supplements reduce tooth loss in the elderly. Am J Med 2001; 111:452–456.

- Amano Y, Komiyama K, Makishima M. Vitamin D and periodontal disease. J Oral Sci 2009; 51:11–20.

- Timms PM, Mannan N, Hitman GA, et al. Circulating MMP9, vitamin D and variation in the TIMP-1 response with VDR genotype: mechanisms for inflammatory damage in chronic disorders? QJM 2002; 95:787–796.