User login

Concurrent colorectal surgery and mesh herniorrhaphy can be done safely, according to findings from a case-matched study based on American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data.

“Our study suggests that mesh repair for [ventral hernia] in the setting of [colorectal surgery] does not worsen 30-day postoperative outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cigdem Benlice and colleagues of the Cleveland Clinic. The study was published in the American Journal of Surgery (2015; 210[4]:766-771]

These two operations are undertaken concurrently in part to save patients from further procedures and anesthesia, but the practice is limited by safety concerns. The complications anticipated include intra-abdominal adhesions, chronic draining sinus, chronic enteric fistula, chronic wound infection, and mesh migration. Any one of these complications could entail further surgical interventions.

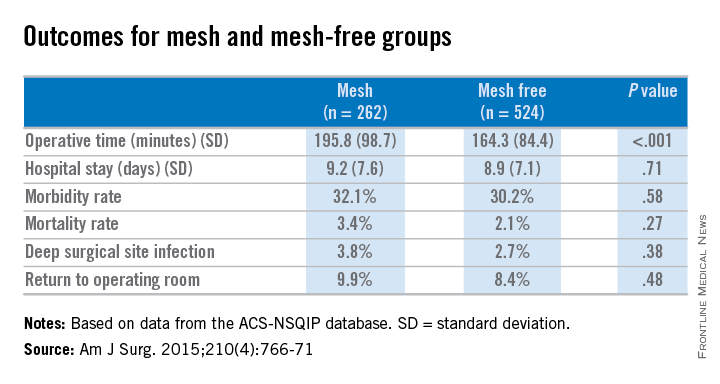

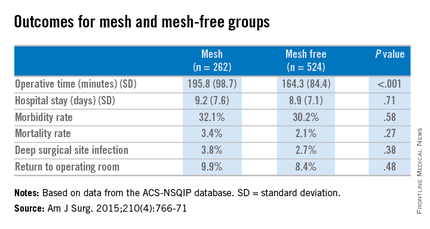

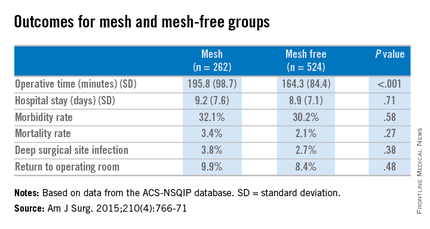

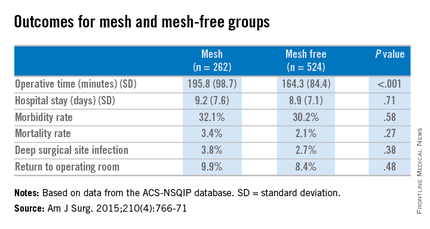

Dr. Benlice and her colleagues used the national, validated, risk-adjusted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database to look at short-term outcomes after concurrent ventral hernia repair (VHR) and colorectal surgery (CS), and the risk factors associated with complications. Data on 2,250 patients having CS and VHR operations simultaneously from 2005 to 2010 were reviewed. Patients having simultaneous VHR with mesh and CS (262) were matched closely with those having both procedures but without mesh (524). The case-matching criteria included diagnosis, type of bowel procedure, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, and follow-up was limited to 30 days.

In a comparison of the mesh and nonmesh groups, morbidity rates were found to be similar (32% vs. 30%, P = .58) as were mortality rates (3.4% vs. 2.1%, P = .27). The rate of deep surgical site infections (3.8% vs. 2.7%, P = .38) were similar between the two groups, and wound disruptions (3.1% vs. 3.1%) rates were the same. The length of hospital stay was also comparable. Mean operating time, however, proved longer in patients who had hernia repair using mesh (196 minutes vs. 164 minutes, P less than .001).

A multivariate analysis showed that open colorectal procedures, III or IV ASA class, smoking, and preoperative open wound or wound infection were significant and independent risk factors (odds ratios, 2.67, 2.51, 2.06, and 2.27, respectively) for surgical site infection.

The limitations of this study reflect some of the limitations of the ACS-NSQIP database. Long-term follow-up, hernia size, type of mesh used, and type of technique used in the operation could not be assessed using the available data. In addition, further analysis of the subgroups of patients with surgical site infections would be needed to examine the impact of mesh (and types of mesh) use on clean-contaminated cases. Researchers noted that at the Cleveland Clinic, type of mesh (biologic vs. nonbiologic) used has been found to have no impact on rates of wound and mesh infection and hernia recurrence, but they were unable to do this kind of analysis with the available data for simultaneous bowel and hernia repair surgery.

The researchers concluded, “the large cohort and strict inclusion, exclusion, and case-matching criteria strengthen the clinical value of this study. When performed simultaneously with CS, VHR with mesh can be performed without increasing perioperative and short-term postoperative morbidity.”

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

Concurrent colorectal surgery and mesh herniorrhaphy can be done safely, according to findings from a case-matched study based on American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data.

“Our study suggests that mesh repair for [ventral hernia] in the setting of [colorectal surgery] does not worsen 30-day postoperative outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cigdem Benlice and colleagues of the Cleveland Clinic. The study was published in the American Journal of Surgery (2015; 210[4]:766-771]

These two operations are undertaken concurrently in part to save patients from further procedures and anesthesia, but the practice is limited by safety concerns. The complications anticipated include intra-abdominal adhesions, chronic draining sinus, chronic enteric fistula, chronic wound infection, and mesh migration. Any one of these complications could entail further surgical interventions.

Dr. Benlice and her colleagues used the national, validated, risk-adjusted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database to look at short-term outcomes after concurrent ventral hernia repair (VHR) and colorectal surgery (CS), and the risk factors associated with complications. Data on 2,250 patients having CS and VHR operations simultaneously from 2005 to 2010 were reviewed. Patients having simultaneous VHR with mesh and CS (262) were matched closely with those having both procedures but without mesh (524). The case-matching criteria included diagnosis, type of bowel procedure, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, and follow-up was limited to 30 days.

In a comparison of the mesh and nonmesh groups, morbidity rates were found to be similar (32% vs. 30%, P = .58) as were mortality rates (3.4% vs. 2.1%, P = .27). The rate of deep surgical site infections (3.8% vs. 2.7%, P = .38) were similar between the two groups, and wound disruptions (3.1% vs. 3.1%) rates were the same. The length of hospital stay was also comparable. Mean operating time, however, proved longer in patients who had hernia repair using mesh (196 minutes vs. 164 minutes, P less than .001).

A multivariate analysis showed that open colorectal procedures, III or IV ASA class, smoking, and preoperative open wound or wound infection were significant and independent risk factors (odds ratios, 2.67, 2.51, 2.06, and 2.27, respectively) for surgical site infection.

The limitations of this study reflect some of the limitations of the ACS-NSQIP database. Long-term follow-up, hernia size, type of mesh used, and type of technique used in the operation could not be assessed using the available data. In addition, further analysis of the subgroups of patients with surgical site infections would be needed to examine the impact of mesh (and types of mesh) use on clean-contaminated cases. Researchers noted that at the Cleveland Clinic, type of mesh (biologic vs. nonbiologic) used has been found to have no impact on rates of wound and mesh infection and hernia recurrence, but they were unable to do this kind of analysis with the available data for simultaneous bowel and hernia repair surgery.

The researchers concluded, “the large cohort and strict inclusion, exclusion, and case-matching criteria strengthen the clinical value of this study. When performed simultaneously with CS, VHR with mesh can be performed without increasing perioperative and short-term postoperative morbidity.”

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

Concurrent colorectal surgery and mesh herniorrhaphy can be done safely, according to findings from a case-matched study based on American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data.

“Our study suggests that mesh repair for [ventral hernia] in the setting of [colorectal surgery] does not worsen 30-day postoperative outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cigdem Benlice and colleagues of the Cleveland Clinic. The study was published in the American Journal of Surgery (2015; 210[4]:766-771]

These two operations are undertaken concurrently in part to save patients from further procedures and anesthesia, but the practice is limited by safety concerns. The complications anticipated include intra-abdominal adhesions, chronic draining sinus, chronic enteric fistula, chronic wound infection, and mesh migration. Any one of these complications could entail further surgical interventions.

Dr. Benlice and her colleagues used the national, validated, risk-adjusted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database to look at short-term outcomes after concurrent ventral hernia repair (VHR) and colorectal surgery (CS), and the risk factors associated with complications. Data on 2,250 patients having CS and VHR operations simultaneously from 2005 to 2010 were reviewed. Patients having simultaneous VHR with mesh and CS (262) were matched closely with those having both procedures but without mesh (524). The case-matching criteria included diagnosis, type of bowel procedure, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, and follow-up was limited to 30 days.

In a comparison of the mesh and nonmesh groups, morbidity rates were found to be similar (32% vs. 30%, P = .58) as were mortality rates (3.4% vs. 2.1%, P = .27). The rate of deep surgical site infections (3.8% vs. 2.7%, P = .38) were similar between the two groups, and wound disruptions (3.1% vs. 3.1%) rates were the same. The length of hospital stay was also comparable. Mean operating time, however, proved longer in patients who had hernia repair using mesh (196 minutes vs. 164 minutes, P less than .001).

A multivariate analysis showed that open colorectal procedures, III or IV ASA class, smoking, and preoperative open wound or wound infection were significant and independent risk factors (odds ratios, 2.67, 2.51, 2.06, and 2.27, respectively) for surgical site infection.

The limitations of this study reflect some of the limitations of the ACS-NSQIP database. Long-term follow-up, hernia size, type of mesh used, and type of technique used in the operation could not be assessed using the available data. In addition, further analysis of the subgroups of patients with surgical site infections would be needed to examine the impact of mesh (and types of mesh) use on clean-contaminated cases. Researchers noted that at the Cleveland Clinic, type of mesh (biologic vs. nonbiologic) used has been found to have no impact on rates of wound and mesh infection and hernia recurrence, but they were unable to do this kind of analysis with the available data for simultaneous bowel and hernia repair surgery.

The researchers concluded, “the large cohort and strict inclusion, exclusion, and case-matching criteria strengthen the clinical value of this study. When performed simultaneously with CS, VHR with mesh can be performed without increasing perioperative and short-term postoperative morbidity.”

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Simultaneous bowel and hernia surgery with mesh are comparable to a nonmesh operation in terms of postoperative morbidity.

Major finding: In a comparison of the mesh and nonmesh groups, morbidity rates were found to be similar (32% vs. 30%, P = .27) as was the rate of deep surgical site infections (3.8% vs. 2.7%, P = .38).

Data source: ACS-NSQIP data on case-matched patients having concurrent bowel and hernia surgery, with mesh (262) and without mesh (524).

Disclosures: The researchers had no relevant disclosures.