User login

Mood disorders spell danger for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Comorbid depression and anxiety often complicate or frustrate treatment of this debilitating—and ultimately fatal—respiratory disease (Box 1).

Managing COPD-related psychiatric disorders is crucial to improving patients’ quality of life. This article presents two cases to address:

- common causes of psychiatric symptoms in patients with COPD

- strategies for effectively treating these symptoms while avoiding adverse effects and drug-drug interactions.

CASE REPORT: COPD AND DEPRESSION

Ms. H, age 59, a pack-a-day smoker since age 19, was diagnosed with COPD 3 years ago. Since then, dyspnea has rendered her unable to work, play with her grandchildren, or walk her dog. She has become increasingly apathetic and tired and is not complying with her prescribed pulmonary rehabilitation. Her primary care physician suspects she is depressed and refers her to a psychiatrist.

COPD is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States after heart disease, malignant neoplasms, and cerebrovascular disease. A total of 122,009 COPD-related deaths were reported in 2000.1

Cigarette smoking causes 80 to 90% of COPD cases.2 Occupational exposure to particles of silica, coal dust, and asbestos also can play a significant role. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency—a rare, genetically transmitted enzyme deficiency—accounts for 0.1% of total cases.

Two disease processes are present in most COPD cases:

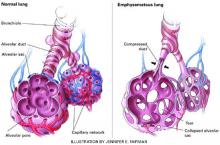

- emphysema, resulting from destruction of air spaces and their associated pulmonary capillaries (Figure)

- chronic bronchitis, causing airway hyperreactivity and increased mucus production.

The first symptom of COPD may be a chronic, productive cough. As the disease progresses, the patient becomes more prone to pulmonary infections, increasingly dyspneic, and unable to exercise. This results in occupational disability, social withdrawal, decreased mobility, and difficulty performing activities of daily living. Initially, an increased respiratory rate keeps oxygen saturation normal. Over time, however, the disease progresses to chronic hypoxia.

End-stage COPD is characterized by chronic hypoxia and retention of carbon dioxide due to inadequate gas exchange. Death results from respiratory failure or from complications such as infections.

During the psychiatrist’s initial interview, Ms. H exhibits anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness, and low energy. She also reports poor sleep and appetite. Her Beck Depression Inventory score of 30 indicates severe major depression.

She is taking inhaled albuterol and ipratropium, 2 puffs each every 6 hours, and has been taking oral prednisone, 10 mg/d, for 5 years. The psychiatrist adds sertraline, 50 mg/d. Her mood, anhedonia, and subjective energy level improve across 2 months. Her Beck Depression Inventory score improves to 6, but her positive responses indicate continued poor appetite, lack of sex drive, and low energy. She often becomes breathless when she tries to eat. Her body mass index is 18, indicating that she is underweight. Caloric nutritional supplements are initiated tid to increase her weight. Her sertraline dose is continued.

Approximately 1 month later, Ms. H is able to begin a pulmonary rehabilitation program, which includes:

- prescribed exercise to increase her endurance during physical activity

- breathing exercises to decrease her breathlessness.

Ms. H also begins attending a support group for patients with COPD.

After 12 weeks of pulmonary rehabilitation, Ms. H is once again able to walk her dog. The psychiatrist continues sertraline, 50 mg/d, because of her high risk of depression recurrence. She continues to smoke despite repeated counseling.

Discussion. This case illustrates how progressing COPD symptoms can compromise a patient’s ability to work, socialize, and enjoy life. The resulting social isolation and loss of independence and self-esteem can lead to depression.3

Forty to 50% of patients with COPD are believed to have comorbid depression compared with 13% of total patients.4 Small sample sizes have limited many prevalence studies, however.4-6

Long-term corticosteroid therapy may also have fueled Ms. H’s depression. Prednisone is associated with dose-related side effects, including depression, anxiety, mania, irritability, and delirium.7

Ms. H’s case also illustrates how depression can derail COPD treatment and predict poorer outcomes of medical treatment in COPD patients.8 Fatigue, apathy, and hopelessness kept her from following her pulmonary rehabilitation regimen.

Treatment. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered first-line treatment for comorbid depressive or anxiety disorders in patients with COPD. These agents are associated with a relatively low incidence of:

- anticholinergic and other side effects

- interactions with other drugs commonly used by COPD patients.

Sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram have fewer side effects and affect the cytochrome P (CYP)-450 pathway to a lesser degree than do other SSRIs.

Venlafaxine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is another first-line option. This agent is associated with dose-dependent increases in blood pressure, so use it with caution in hypertensive patients.

Mirtazapine, which has been shown to stimulate appetite, can be considered for patients with prominent anorexia or if dyspnea frequently interferes with eating.

Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors are rarely considered first-line for COPD patients but may help in some clinical instances, such as in younger or middle-aged patients with chronic pain. Dosages for chronic pain generally are much lower than therapeutic dosages for depression. For example, amitriptyline is usually given at 25 mg/d for chronic pain and at 50 to 100 mg/dfor depression.

Table 1

Interactions between selected psychotropics and drugs used by COPD patients

| Psychotropic | Potential interactions |

|---|---|

| Alprazolam | Itraconazole, fluconazole, cimetidine increase alprazolam levels |

| Bupropion | Lowers seizure threshold, so use with other drugs with seizure-causing potential (eg, theophylline) requires caution May increase adverse effects of levodopa, amantadine |

| Buspirone | Erythromycin, itraconazole increase buspirone levels |

| Diazepam, lorazepam | Theophylline may decrease serum levels of these drugs |

| Divalproex | May increase prothrombin time and INR* in patients taking warfarin |

| Fluoxetine | May increase prothrombin time and INR in patients taking warfarin |

| Nefazodone | Could increase atorvastatin, simvastatin levels |

| Paroxetine | May interact with warfarin Cimetidine increases paroxetine levels Reports of increased theophylline levels |

| Risperidone | Metabolized by CYP-450 2D6 enzyme; potential exists for interactions, but none reported |

| INR: International normalized ratio, a standardized measurement of warfarin therapy effectiveness. | |

Tricyclics, however, may cause excessive sedation, orthostatic hypotension, confusion, constipation, and urinary retention. These effects can be debilitating in older patients.

Nefazodone is a potent inhibitor of the CYP-450 3A4 isoenzyme and may increase levels of triazolam and alprazolam. Levels of the lipid-lowering agents atorvastatin and simvastatin may increase threefold to fourfold when nefazodone is added. Use nefazodone with caution in patients taking digoxin, because nefazodone is 99% bound to serum proteins and may increase serum digoxin to a dangerous level. Nefazodone also carries a risk of hepatic failure, so hepatic enzyme levels should be monitored.9

Figure Destruction of air spaces and capillaries in emphysema

Many COPD patients have a mixture of emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Emphysema is characterized by damaged alveoli, loss of elasticity of airways (bronchioles and alveoli), alveoli compression and collapse, tearing of alveoli walls, and bullae formation. In chronic bronchitis, the bronchial walls are inflamed and thickened, with a narrowing and plugging of the bronchial airways.Table 1 lists selected psychotropics and their potential interactions with drugs commonly taken by COPD patients.

CASE REPORT: COPD AND ANXIETY

Ms. P, age 60, is hospitalized for an exacerbation of COPD, which was diagnosed 10 years ago. She is intubated and ventilated after developing pneumonia-related respiratory failure. After a 2-week hospitalization, her pulmonologist tries to wean her off the ventilator, but episodes of panic and dyspnea result in significant oxygen desaturations.

The patient is transferred to a rehabilitation facility. A psychiatrist is consulted and discovers a 10-year history of anxiety that had been managed with lorazepam, 1 mg tid, and sertraline, 50 mg/d.

On evaluation, Ms. P is sweating, tremulous, and hyperventilating. She cannot speak, mouth words, or nod because of her respiratory distress. During her hospitalization she has been receiving albuterol and ipratropium nebulized every 4 hours; intravenous methylprednisolone, weaned from 40 mg to 10 mg every 6 hours; sertraline, 50 mg/d; clonazepam, 1 mg qid; theophylline, 400 mg/d, and several intravenous antibiotics. Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg bid, was recently added for a urinary tract infection.

Table 2

Drugs commonly used to treat COPD and their potential psychiatric side effects

| Drug | Action | Possible psychiatric side effect |

|---|---|---|

| Albuterol | Short-acting bronchodilator | Anxiety |

| Salmeterol | Long-acting bronchodilator | Anxiety, especially if used more than twice daily |

| Ipratropium | Inhaled anticholinergic | None |

| Inhaled corticosteroid (eg, fluticasone, budesonide) | Anti-inflammatory | None |

| Oral corticosteroid (prednisone, methylprednisolone) | Anti-inflammatory | Depression, anxiety, mania, delirium |

| Montelukast tablets or chewable tablets | Possibly both anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator activity | None |

| Theophylline | Anti-inflammatory and respiratory stimulant | Anxiety, especially if blood level is >20 μg/mL |

Ms. P’s mental status alternates between severe anxiety and obtundation. When her anxiety becomes acute, the attending physician prescribes intravenous lorazepam, 1 to 2 mg as needed. Her chart reveals that she has received 4 to 6 mg of lorazepam each day.

A blood test reveals a toxic theophylline level of 20 mg/mL. Acting on the psychiatrist’s suggestion, Ms. P’s physician decreases theophylline to 200 mg/d. Her anxiety improves slightly, but episodes of panic continue to block attempts to wean her from the ventilator. The psychiatrist increases sertraline to 100 mg/d and stops lorazepam. She adds gabapentin, 300 mg every 8 hours.

Within 3 days, Ms. P’s obtundation ceases and she is less tremulous and panicked. She can mouth words and answer questions by nodding. Within 1 week, her anxiety is improved. Five days later, she is weaned from the ventilator. The facility’s psychologist teaches her relaxation, visualization, and breathing exercises to counteract panic and anxiety.

Ms. P is discharged 2 weeks later, after beginning a pulmonary rehabilitation program. Her primary care physician weans her off clonazepam, and her gabapentin and sertraline dosages are continued.

Discussion. Although the estimated prevalence of anxiety among patients with COPD varies widely,10 anxiety is more prevalent in patients with severe lung disease.11

Panic attacks and anxiety in COPD have been linked to hypoxia, hypercapnia, and hypocapnia. Hyperventilation leads to a decrease in pCO2 , causing a respiratory alkalosis that leads to cerebral vasoconstriction. This ultimately results in anxiety symptoms.

Communication with other care team members is crucial to psychiatric treatment of patients with COPD. To ensure proper coordination of care:

- Medication history. Report changes in psychiatric medication to all doctors. Obtain from the primary care physician a complete list of the patient’s medications and medical problems to prevent drug-drug interactions.

- Onset of depression, anxiety. Report warning signs of depression and anxiety to other care team members, and urge doctors to refer patients who exhibit these signs. Primary care physicians often miss these potential warning signs:

- Suicidality. Alert other doctors to the warning signs of suicidality. Patients older than 65 and those with depression or chronic health problems are at increased risk of suicide. Many patients with COPD exhibit the following risk factors:

In patients with severe COPD, chronic hypoventilation increases pCO 2 levels. This has been shown in animals to activate a medullary chemoreceptor, which elicits a panic response by activating neurons in the locus ceruleus.

Lactic acid, formed because of hypoxia, is also linked to panic attacks. Investigators have postulated that persons with both panic disorder and COPD are hypersensitive to lactic acid and hyperventilation.12

In some patients, shortness of breath causes anticipatory anxiety that can further decrease activity and worsen deconditioning.

The crippling fear that comes with an anxiety or panic disorder can also complicate COPD therapy. Panic and anxiety often interfere with weaning from mechanical ventilation, despite treatment with high-dose benzodiazepines in some cases.13 The more frequent or protracted the use of ventilation, the greater the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.

COPD drugs that cause anxiety. A comprehensive review of the patient’s medications and lab readings is crucial to planning treatment. Ms. P was concomitantly taking several drugs for COPD that can cause anxiety or panic symptoms (Table 2):

- Bronchodilators such as albuterol are agonists that can increase heart rate and cause anxiety associated with rapid heartbeat.

- Theophylline, which may act as a bronchodilator and respiratory stimulant, can cause anxiety, especially at blood levels >20 mg/mL. In Ms. P’s case, the combination of ciprofloxacin and theophylline caused a CYP-450 interaction that increased her theophylline level. This is because ciprofloxacin and most other quinolone antibiotics are CYP 1A2 inducers, whereas theophylline is a CYP 1A2 substrate.9

- High-dose corticosteroids (eg, methylprednisolone) also may contribute to anxiety.

Treatment. SSRIs are an accepted first-line therapy for COPD-related anxiety. Buspirone may also work in some COPD patients. Anticonvulsants such as gabapentin and divalproex are possible adjuncts to antidepressants.

Routine use of benzodiazepines is not recommended to treat anxiety in COPD for several reasons:

- These agents can cause respiratory depression in higher doses and thus may be dangerous to patients with end-stage COPD. Reports indicate that benzodiazepines may worsen pulmonary status.14

- Rebound anxiety may occur when the drug is cleared from the system. This may accelerate benzodiazepine use, which can lead to excessively high doses and/or addiction.

Antihistamines such as hydroxyzine are a nonaddictive alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety control. They may be used as an adjunct to antidepressants if alcohol or drug addiction are present. These agents, however, may have sedating and anticholinergic side effects.

Beta blockers, commonly used to treat performance anxiety, may worsen pulmonary status and are contraindicated in COPD patients.

COPD and comorbidities. Many patients with COPD are taking several medications for comorbid hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, or congestive heart failure. These other conditions or medications may contribute to psychiatric symptoms, diminish the effectiveness of psychiatric treatment, or cause an adverse interaction with a psychotropic.

A thorough review of the patient’s medical records is strongly recommended. Communication with other care team members is critical (Box 2).

PSYCHOSOCIAL TREATMENT

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may be effective in treating COPD-related anxiety and depression. CBT involves the correction of unrealistic and harmful thought patterns (such as cat-astrophizing shortness of breath) through techniques such as guided imagery and relaxation. Breathing exercises are also used.6

Medically stable patients can be taught “interoceptive exposure” techniques by learning to induce panic symptoms in a controlled setting (such as by hyperventilating in the doctor’s office), then desensitizing themselves to the anxiety. Exposure can also be used in social settings to accustom the patient to feared stimuli.

Support groups can increase social interaction and offer a chance to discuss disease-related medical, psychological, and social issues with other COPD patients.

Pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to decrease depression and anxiety, increase functioning, and promote independence in patients with COPD.12 Patients are educated about their disease and learn breathing techniques to reduce air hunger and exercises to optimize oxygen use.

Physical exercise figures prominently in pulmonary rehabilitation by improving oxygen consumption efficiency. This in turn improves exercise tolerance.15

COPD AND DELIRIUM

Delirium is common among older patients with COPD. Two or more causes can be at work simultaneously, such as:

- hypoxia and hypercapnia

- reactions to antibiotics, antivirals, and corticosteroids used to treat COPD.

Delirium can simulate depression, anxiety, mania, and psychosis because affective lability, fluctuating levels of consciousness, and impaired reality testing are features of delirium.

A COPD patient’s sudden change in mental status should prompt a careful review of medications and medical conditions and an oxygen saturation measurement. An arterial blood gas reading may also be helpful because hypercapnia can be present without hypoxia. The sudden onset of psychotic symptoms in a patient with COPD should also prompt a thorough search for causes of delirium.16

Related resources

- Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al (eds.). Harrison’s principles of internal medicine (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing, 2001.

- American Lung Association: Around the clock with COPD. http://www.lungusa.org/diseases/copd_clock.html

- National Emphysema Foundation. http://www.emphysemafoundation.org/

Drug brand names

- Albuterol • Proventil, Ventolin

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amantadine • Symmetrel

- Atorvastatin • Lipitor

- Budesonide • Pulmicort

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Cimetidine • Tagamet

- Ciprofloxacin • Ciloxan, Cipro

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Diazepam • Valium

- Digoxin • Lanoxin

- Divalproex • Depakote

- Erythromycin • Emgel, others

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluconazole • Diflucan

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluticasone • Flovent

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Hydroxyzine • Atarax, Vistaril

- Ipratropium • Atrovent

- Itraconazole • Sporanox

- Levodopa • Sinemet

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Montelukast • Singulair

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Salmeterol • Serevent

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Simvastatin • Zocor

- Theophylline • Theo-dur, others

- Triazolam • Halcion

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Warfarin • Coumadin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: Leading causes for 2000. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2002;50(6):8.-Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs. Accessed October 16, 2003.

2. American Lung Association fact sheet: COPD. Available at: http://www.lungusa.org/diseases/copd_factsheet.html. Accessed Sept. 23, 2003.

3. American Lung Association: Breathless in America Available at: http://www.lungusa.org/press/lung_dis/asn_copd21601.html. Accessed Sept. 8, 2003.

4. Gift AG, McCrone SH. Depression in patients with COPD. Heart Lung 1993;22:289-97.

5. Light RW, Merrill EJ, Despars JA, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Chest 1985;87:35-8.

6. Dudley DL, Glaser EM, Jorgenson BN, Logan DL. Psychosocial concomitants to rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Part 2: psychosocial treatment. Chest 1980;77:544-51.

7. Wise MG, Rundell JR (eds). Textbook of consultation-liaison psychiatry: psychiatry in the medically ill. (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2002.

8. Dahlen I, Janson C. Anxiety and depression are related to the outcome of emergency treatment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2002;122:1633-7.

9. Physicians’ Desk Reference (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003.

10. Karajgi B, Rifkin A, Doddi S, Kolli R. The prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:200-1.

11. Porzelius J, Vest M, Nochomovitz M. Respiratory function, cognitions, and panic in chronic obstructive pulmonary patients. Behav Res Ther 1992;30:75-7.

12. Smoller JW, Pollack MH. Panic anxiety, dyspnea, and respiratory disease. Theoretical and clinical considerations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:6-17.

13. Mendel JG, Kahn FA. Psychosocial aspects of weaning from mechanical ventilation. Psychosomatics 1980;21:465-71.

14. Man GCW, Hsu K, Sproule BJ. Effect of alprazolam on exercise and dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 1986;90:832-6.

15. Ries AL, Kaplan RM, Limberg TM, Prewitt LM. Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on physiologic and psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:823-32.

16. Yudofsky SC, Hales RE (eds). Textbook of neuropsychiatry. (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1997;447-70.

Mood disorders spell danger for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Comorbid depression and anxiety often complicate or frustrate treatment of this debilitating—and ultimately fatal—respiratory disease (Box 1).

Managing COPD-related psychiatric disorders is crucial to improving patients’ quality of life. This article presents two cases to address:

- common causes of psychiatric symptoms in patients with COPD

- strategies for effectively treating these symptoms while avoiding adverse effects and drug-drug interactions.

CASE REPORT: COPD AND DEPRESSION

Ms. H, age 59, a pack-a-day smoker since age 19, was diagnosed with COPD 3 years ago. Since then, dyspnea has rendered her unable to work, play with her grandchildren, or walk her dog. She has become increasingly apathetic and tired and is not complying with her prescribed pulmonary rehabilitation. Her primary care physician suspects she is depressed and refers her to a psychiatrist.

COPD is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States after heart disease, malignant neoplasms, and cerebrovascular disease. A total of 122,009 COPD-related deaths were reported in 2000.1

Cigarette smoking causes 80 to 90% of COPD cases.2 Occupational exposure to particles of silica, coal dust, and asbestos also can play a significant role. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency—a rare, genetically transmitted enzyme deficiency—accounts for 0.1% of total cases.

Two disease processes are present in most COPD cases:

- emphysema, resulting from destruction of air spaces and their associated pulmonary capillaries (Figure)

- chronic bronchitis, causing airway hyperreactivity and increased mucus production.

The first symptom of COPD may be a chronic, productive cough. As the disease progresses, the patient becomes more prone to pulmonary infections, increasingly dyspneic, and unable to exercise. This results in occupational disability, social withdrawal, decreased mobility, and difficulty performing activities of daily living. Initially, an increased respiratory rate keeps oxygen saturation normal. Over time, however, the disease progresses to chronic hypoxia.

End-stage COPD is characterized by chronic hypoxia and retention of carbon dioxide due to inadequate gas exchange. Death results from respiratory failure or from complications such as infections.

During the psychiatrist’s initial interview, Ms. H exhibits anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness, and low energy. She also reports poor sleep and appetite. Her Beck Depression Inventory score of 30 indicates severe major depression.

She is taking inhaled albuterol and ipratropium, 2 puffs each every 6 hours, and has been taking oral prednisone, 10 mg/d, for 5 years. The psychiatrist adds sertraline, 50 mg/d. Her mood, anhedonia, and subjective energy level improve across 2 months. Her Beck Depression Inventory score improves to 6, but her positive responses indicate continued poor appetite, lack of sex drive, and low energy. She often becomes breathless when she tries to eat. Her body mass index is 18, indicating that she is underweight. Caloric nutritional supplements are initiated tid to increase her weight. Her sertraline dose is continued.

Approximately 1 month later, Ms. H is able to begin a pulmonary rehabilitation program, which includes:

- prescribed exercise to increase her endurance during physical activity

- breathing exercises to decrease her breathlessness.

Ms. H also begins attending a support group for patients with COPD.

After 12 weeks of pulmonary rehabilitation, Ms. H is once again able to walk her dog. The psychiatrist continues sertraline, 50 mg/d, because of her high risk of depression recurrence. She continues to smoke despite repeated counseling.

Discussion. This case illustrates how progressing COPD symptoms can compromise a patient’s ability to work, socialize, and enjoy life. The resulting social isolation and loss of independence and self-esteem can lead to depression.3

Forty to 50% of patients with COPD are believed to have comorbid depression compared with 13% of total patients.4 Small sample sizes have limited many prevalence studies, however.4-6

Long-term corticosteroid therapy may also have fueled Ms. H’s depression. Prednisone is associated with dose-related side effects, including depression, anxiety, mania, irritability, and delirium.7

Ms. H’s case also illustrates how depression can derail COPD treatment and predict poorer outcomes of medical treatment in COPD patients.8 Fatigue, apathy, and hopelessness kept her from following her pulmonary rehabilitation regimen.

Treatment. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered first-line treatment for comorbid depressive or anxiety disorders in patients with COPD. These agents are associated with a relatively low incidence of:

- anticholinergic and other side effects

- interactions with other drugs commonly used by COPD patients.

Sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram have fewer side effects and affect the cytochrome P (CYP)-450 pathway to a lesser degree than do other SSRIs.

Venlafaxine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is another first-line option. This agent is associated with dose-dependent increases in blood pressure, so use it with caution in hypertensive patients.

Mirtazapine, which has been shown to stimulate appetite, can be considered for patients with prominent anorexia or if dyspnea frequently interferes with eating.

Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors are rarely considered first-line for COPD patients but may help in some clinical instances, such as in younger or middle-aged patients with chronic pain. Dosages for chronic pain generally are much lower than therapeutic dosages for depression. For example, amitriptyline is usually given at 25 mg/d for chronic pain and at 50 to 100 mg/dfor depression.

Table 1

Interactions between selected psychotropics and drugs used by COPD patients

| Psychotropic | Potential interactions |

|---|---|

| Alprazolam | Itraconazole, fluconazole, cimetidine increase alprazolam levels |

| Bupropion | Lowers seizure threshold, so use with other drugs with seizure-causing potential (eg, theophylline) requires caution May increase adverse effects of levodopa, amantadine |

| Buspirone | Erythromycin, itraconazole increase buspirone levels |

| Diazepam, lorazepam | Theophylline may decrease serum levels of these drugs |

| Divalproex | May increase prothrombin time and INR* in patients taking warfarin |

| Fluoxetine | May increase prothrombin time and INR in patients taking warfarin |

| Nefazodone | Could increase atorvastatin, simvastatin levels |

| Paroxetine | May interact with warfarin Cimetidine increases paroxetine levels Reports of increased theophylline levels |

| Risperidone | Metabolized by CYP-450 2D6 enzyme; potential exists for interactions, but none reported |

| INR: International normalized ratio, a standardized measurement of warfarin therapy effectiveness. | |

Tricyclics, however, may cause excessive sedation, orthostatic hypotension, confusion, constipation, and urinary retention. These effects can be debilitating in older patients.

Nefazodone is a potent inhibitor of the CYP-450 3A4 isoenzyme and may increase levels of triazolam and alprazolam. Levels of the lipid-lowering agents atorvastatin and simvastatin may increase threefold to fourfold when nefazodone is added. Use nefazodone with caution in patients taking digoxin, because nefazodone is 99% bound to serum proteins and may increase serum digoxin to a dangerous level. Nefazodone also carries a risk of hepatic failure, so hepatic enzyme levels should be monitored.9

Figure Destruction of air spaces and capillaries in emphysema

Many COPD patients have a mixture of emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Emphysema is characterized by damaged alveoli, loss of elasticity of airways (bronchioles and alveoli), alveoli compression and collapse, tearing of alveoli walls, and bullae formation. In chronic bronchitis, the bronchial walls are inflamed and thickened, with a narrowing and plugging of the bronchial airways.Table 1 lists selected psychotropics and their potential interactions with drugs commonly taken by COPD patients.

CASE REPORT: COPD AND ANXIETY

Ms. P, age 60, is hospitalized for an exacerbation of COPD, which was diagnosed 10 years ago. She is intubated and ventilated after developing pneumonia-related respiratory failure. After a 2-week hospitalization, her pulmonologist tries to wean her off the ventilator, but episodes of panic and dyspnea result in significant oxygen desaturations.

The patient is transferred to a rehabilitation facility. A psychiatrist is consulted and discovers a 10-year history of anxiety that had been managed with lorazepam, 1 mg tid, and sertraline, 50 mg/d.

On evaluation, Ms. P is sweating, tremulous, and hyperventilating. She cannot speak, mouth words, or nod because of her respiratory distress. During her hospitalization she has been receiving albuterol and ipratropium nebulized every 4 hours; intravenous methylprednisolone, weaned from 40 mg to 10 mg every 6 hours; sertraline, 50 mg/d; clonazepam, 1 mg qid; theophylline, 400 mg/d, and several intravenous antibiotics. Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg bid, was recently added for a urinary tract infection.

Table 2

Drugs commonly used to treat COPD and their potential psychiatric side effects

| Drug | Action | Possible psychiatric side effect |

|---|---|---|

| Albuterol | Short-acting bronchodilator | Anxiety |

| Salmeterol | Long-acting bronchodilator | Anxiety, especially if used more than twice daily |

| Ipratropium | Inhaled anticholinergic | None |

| Inhaled corticosteroid (eg, fluticasone, budesonide) | Anti-inflammatory | None |

| Oral corticosteroid (prednisone, methylprednisolone) | Anti-inflammatory | Depression, anxiety, mania, delirium |

| Montelukast tablets or chewable tablets | Possibly both anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator activity | None |

| Theophylline | Anti-inflammatory and respiratory stimulant | Anxiety, especially if blood level is >20 μg/mL |

Ms. P’s mental status alternates between severe anxiety and obtundation. When her anxiety becomes acute, the attending physician prescribes intravenous lorazepam, 1 to 2 mg as needed. Her chart reveals that she has received 4 to 6 mg of lorazepam each day.

A blood test reveals a toxic theophylline level of 20 mg/mL. Acting on the psychiatrist’s suggestion, Ms. P’s physician decreases theophylline to 200 mg/d. Her anxiety improves slightly, but episodes of panic continue to block attempts to wean her from the ventilator. The psychiatrist increases sertraline to 100 mg/d and stops lorazepam. She adds gabapentin, 300 mg every 8 hours.

Within 3 days, Ms. P’s obtundation ceases and she is less tremulous and panicked. She can mouth words and answer questions by nodding. Within 1 week, her anxiety is improved. Five days later, she is weaned from the ventilator. The facility’s psychologist teaches her relaxation, visualization, and breathing exercises to counteract panic and anxiety.

Ms. P is discharged 2 weeks later, after beginning a pulmonary rehabilitation program. Her primary care physician weans her off clonazepam, and her gabapentin and sertraline dosages are continued.

Discussion. Although the estimated prevalence of anxiety among patients with COPD varies widely,10 anxiety is more prevalent in patients with severe lung disease.11

Panic attacks and anxiety in COPD have been linked to hypoxia, hypercapnia, and hypocapnia. Hyperventilation leads to a decrease in pCO2 , causing a respiratory alkalosis that leads to cerebral vasoconstriction. This ultimately results in anxiety symptoms.

Communication with other care team members is crucial to psychiatric treatment of patients with COPD. To ensure proper coordination of care:

- Medication history. Report changes in psychiatric medication to all doctors. Obtain from the primary care physician a complete list of the patient’s medications and medical problems to prevent drug-drug interactions.

- Onset of depression, anxiety. Report warning signs of depression and anxiety to other care team members, and urge doctors to refer patients who exhibit these signs. Primary care physicians often miss these potential warning signs:

- Suicidality. Alert other doctors to the warning signs of suicidality. Patients older than 65 and those with depression or chronic health problems are at increased risk of suicide. Many patients with COPD exhibit the following risk factors:

In patients with severe COPD, chronic hypoventilation increases pCO 2 levels. This has been shown in animals to activate a medullary chemoreceptor, which elicits a panic response by activating neurons in the locus ceruleus.

Lactic acid, formed because of hypoxia, is also linked to panic attacks. Investigators have postulated that persons with both panic disorder and COPD are hypersensitive to lactic acid and hyperventilation.12

In some patients, shortness of breath causes anticipatory anxiety that can further decrease activity and worsen deconditioning.

The crippling fear that comes with an anxiety or panic disorder can also complicate COPD therapy. Panic and anxiety often interfere with weaning from mechanical ventilation, despite treatment with high-dose benzodiazepines in some cases.13 The more frequent or protracted the use of ventilation, the greater the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.

COPD drugs that cause anxiety. A comprehensive review of the patient’s medications and lab readings is crucial to planning treatment. Ms. P was concomitantly taking several drugs for COPD that can cause anxiety or panic symptoms (Table 2):

- Bronchodilators such as albuterol are agonists that can increase heart rate and cause anxiety associated with rapid heartbeat.

- Theophylline, which may act as a bronchodilator and respiratory stimulant, can cause anxiety, especially at blood levels >20 mg/mL. In Ms. P’s case, the combination of ciprofloxacin and theophylline caused a CYP-450 interaction that increased her theophylline level. This is because ciprofloxacin and most other quinolone antibiotics are CYP 1A2 inducers, whereas theophylline is a CYP 1A2 substrate.9

- High-dose corticosteroids (eg, methylprednisolone) also may contribute to anxiety.

Treatment. SSRIs are an accepted first-line therapy for COPD-related anxiety. Buspirone may also work in some COPD patients. Anticonvulsants such as gabapentin and divalproex are possible adjuncts to antidepressants.

Routine use of benzodiazepines is not recommended to treat anxiety in COPD for several reasons:

- These agents can cause respiratory depression in higher doses and thus may be dangerous to patients with end-stage COPD. Reports indicate that benzodiazepines may worsen pulmonary status.14

- Rebound anxiety may occur when the drug is cleared from the system. This may accelerate benzodiazepine use, which can lead to excessively high doses and/or addiction.

Antihistamines such as hydroxyzine are a nonaddictive alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety control. They may be used as an adjunct to antidepressants if alcohol or drug addiction are present. These agents, however, may have sedating and anticholinergic side effects.

Beta blockers, commonly used to treat performance anxiety, may worsen pulmonary status and are contraindicated in COPD patients.

COPD and comorbidities. Many patients with COPD are taking several medications for comorbid hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, or congestive heart failure. These other conditions or medications may contribute to psychiatric symptoms, diminish the effectiveness of psychiatric treatment, or cause an adverse interaction with a psychotropic.

A thorough review of the patient’s medical records is strongly recommended. Communication with other care team members is critical (Box 2).

PSYCHOSOCIAL TREATMENT

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may be effective in treating COPD-related anxiety and depression. CBT involves the correction of unrealistic and harmful thought patterns (such as cat-astrophizing shortness of breath) through techniques such as guided imagery and relaxation. Breathing exercises are also used.6

Medically stable patients can be taught “interoceptive exposure” techniques by learning to induce panic symptoms in a controlled setting (such as by hyperventilating in the doctor’s office), then desensitizing themselves to the anxiety. Exposure can also be used in social settings to accustom the patient to feared stimuli.

Support groups can increase social interaction and offer a chance to discuss disease-related medical, psychological, and social issues with other COPD patients.

Pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to decrease depression and anxiety, increase functioning, and promote independence in patients with COPD.12 Patients are educated about their disease and learn breathing techniques to reduce air hunger and exercises to optimize oxygen use.

Physical exercise figures prominently in pulmonary rehabilitation by improving oxygen consumption efficiency. This in turn improves exercise tolerance.15

COPD AND DELIRIUM

Delirium is common among older patients with COPD. Two or more causes can be at work simultaneously, such as:

- hypoxia and hypercapnia

- reactions to antibiotics, antivirals, and corticosteroids used to treat COPD.

Delirium can simulate depression, anxiety, mania, and psychosis because affective lability, fluctuating levels of consciousness, and impaired reality testing are features of delirium.

A COPD patient’s sudden change in mental status should prompt a careful review of medications and medical conditions and an oxygen saturation measurement. An arterial blood gas reading may also be helpful because hypercapnia can be present without hypoxia. The sudden onset of psychotic symptoms in a patient with COPD should also prompt a thorough search for causes of delirium.16

Related resources

- Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al (eds.). Harrison’s principles of internal medicine (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing, 2001.

- American Lung Association: Around the clock with COPD. http://www.lungusa.org/diseases/copd_clock.html

- National Emphysema Foundation. http://www.emphysemafoundation.org/

Drug brand names

- Albuterol • Proventil, Ventolin

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amantadine • Symmetrel

- Atorvastatin • Lipitor

- Budesonide • Pulmicort

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Cimetidine • Tagamet

- Ciprofloxacin • Ciloxan, Cipro

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Diazepam • Valium

- Digoxin • Lanoxin

- Divalproex • Depakote

- Erythromycin • Emgel, others

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluconazole • Diflucan

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluticasone • Flovent

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Hydroxyzine • Atarax, Vistaril

- Ipratropium • Atrovent

- Itraconazole • Sporanox

- Levodopa • Sinemet

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Montelukast • Singulair

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Salmeterol • Serevent

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Simvastatin • Zocor

- Theophylline • Theo-dur, others

- Triazolam • Halcion

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Warfarin • Coumadin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Mood disorders spell danger for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Comorbid depression and anxiety often complicate or frustrate treatment of this debilitating—and ultimately fatal—respiratory disease (Box 1).

Managing COPD-related psychiatric disorders is crucial to improving patients’ quality of life. This article presents two cases to address:

- common causes of psychiatric symptoms in patients with COPD

- strategies for effectively treating these symptoms while avoiding adverse effects and drug-drug interactions.

CASE REPORT: COPD AND DEPRESSION

Ms. H, age 59, a pack-a-day smoker since age 19, was diagnosed with COPD 3 years ago. Since then, dyspnea has rendered her unable to work, play with her grandchildren, or walk her dog. She has become increasingly apathetic and tired and is not complying with her prescribed pulmonary rehabilitation. Her primary care physician suspects she is depressed and refers her to a psychiatrist.

COPD is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States after heart disease, malignant neoplasms, and cerebrovascular disease. A total of 122,009 COPD-related deaths were reported in 2000.1

Cigarette smoking causes 80 to 90% of COPD cases.2 Occupational exposure to particles of silica, coal dust, and asbestos also can play a significant role. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency—a rare, genetically transmitted enzyme deficiency—accounts for 0.1% of total cases.

Two disease processes are present in most COPD cases:

- emphysema, resulting from destruction of air spaces and their associated pulmonary capillaries (Figure)

- chronic bronchitis, causing airway hyperreactivity and increased mucus production.

The first symptom of COPD may be a chronic, productive cough. As the disease progresses, the patient becomes more prone to pulmonary infections, increasingly dyspneic, and unable to exercise. This results in occupational disability, social withdrawal, decreased mobility, and difficulty performing activities of daily living. Initially, an increased respiratory rate keeps oxygen saturation normal. Over time, however, the disease progresses to chronic hypoxia.

End-stage COPD is characterized by chronic hypoxia and retention of carbon dioxide due to inadequate gas exchange. Death results from respiratory failure or from complications such as infections.

During the psychiatrist’s initial interview, Ms. H exhibits anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness, and low energy. She also reports poor sleep and appetite. Her Beck Depression Inventory score of 30 indicates severe major depression.

She is taking inhaled albuterol and ipratropium, 2 puffs each every 6 hours, and has been taking oral prednisone, 10 mg/d, for 5 years. The psychiatrist adds sertraline, 50 mg/d. Her mood, anhedonia, and subjective energy level improve across 2 months. Her Beck Depression Inventory score improves to 6, but her positive responses indicate continued poor appetite, lack of sex drive, and low energy. She often becomes breathless when she tries to eat. Her body mass index is 18, indicating that she is underweight. Caloric nutritional supplements are initiated tid to increase her weight. Her sertraline dose is continued.

Approximately 1 month later, Ms. H is able to begin a pulmonary rehabilitation program, which includes:

- prescribed exercise to increase her endurance during physical activity

- breathing exercises to decrease her breathlessness.

Ms. H also begins attending a support group for patients with COPD.

After 12 weeks of pulmonary rehabilitation, Ms. H is once again able to walk her dog. The psychiatrist continues sertraline, 50 mg/d, because of her high risk of depression recurrence. She continues to smoke despite repeated counseling.

Discussion. This case illustrates how progressing COPD symptoms can compromise a patient’s ability to work, socialize, and enjoy life. The resulting social isolation and loss of independence and self-esteem can lead to depression.3

Forty to 50% of patients with COPD are believed to have comorbid depression compared with 13% of total patients.4 Small sample sizes have limited many prevalence studies, however.4-6

Long-term corticosteroid therapy may also have fueled Ms. H’s depression. Prednisone is associated with dose-related side effects, including depression, anxiety, mania, irritability, and delirium.7

Ms. H’s case also illustrates how depression can derail COPD treatment and predict poorer outcomes of medical treatment in COPD patients.8 Fatigue, apathy, and hopelessness kept her from following her pulmonary rehabilitation regimen.

Treatment. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered first-line treatment for comorbid depressive or anxiety disorders in patients with COPD. These agents are associated with a relatively low incidence of:

- anticholinergic and other side effects

- interactions with other drugs commonly used by COPD patients.

Sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram have fewer side effects and affect the cytochrome P (CYP)-450 pathway to a lesser degree than do other SSRIs.

Venlafaxine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is another first-line option. This agent is associated with dose-dependent increases in blood pressure, so use it with caution in hypertensive patients.

Mirtazapine, which has been shown to stimulate appetite, can be considered for patients with prominent anorexia or if dyspnea frequently interferes with eating.

Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors are rarely considered first-line for COPD patients but may help in some clinical instances, such as in younger or middle-aged patients with chronic pain. Dosages for chronic pain generally are much lower than therapeutic dosages for depression. For example, amitriptyline is usually given at 25 mg/d for chronic pain and at 50 to 100 mg/dfor depression.

Table 1

Interactions between selected psychotropics and drugs used by COPD patients

| Psychotropic | Potential interactions |

|---|---|

| Alprazolam | Itraconazole, fluconazole, cimetidine increase alprazolam levels |

| Bupropion | Lowers seizure threshold, so use with other drugs with seizure-causing potential (eg, theophylline) requires caution May increase adverse effects of levodopa, amantadine |

| Buspirone | Erythromycin, itraconazole increase buspirone levels |

| Diazepam, lorazepam | Theophylline may decrease serum levels of these drugs |

| Divalproex | May increase prothrombin time and INR* in patients taking warfarin |

| Fluoxetine | May increase prothrombin time and INR in patients taking warfarin |

| Nefazodone | Could increase atorvastatin, simvastatin levels |

| Paroxetine | May interact with warfarin Cimetidine increases paroxetine levels Reports of increased theophylline levels |

| Risperidone | Metabolized by CYP-450 2D6 enzyme; potential exists for interactions, but none reported |

| INR: International normalized ratio, a standardized measurement of warfarin therapy effectiveness. | |

Tricyclics, however, may cause excessive sedation, orthostatic hypotension, confusion, constipation, and urinary retention. These effects can be debilitating in older patients.

Nefazodone is a potent inhibitor of the CYP-450 3A4 isoenzyme and may increase levels of triazolam and alprazolam. Levels of the lipid-lowering agents atorvastatin and simvastatin may increase threefold to fourfold when nefazodone is added. Use nefazodone with caution in patients taking digoxin, because nefazodone is 99% bound to serum proteins and may increase serum digoxin to a dangerous level. Nefazodone also carries a risk of hepatic failure, so hepatic enzyme levels should be monitored.9

Figure Destruction of air spaces and capillaries in emphysema

Many COPD patients have a mixture of emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Emphysema is characterized by damaged alveoli, loss of elasticity of airways (bronchioles and alveoli), alveoli compression and collapse, tearing of alveoli walls, and bullae formation. In chronic bronchitis, the bronchial walls are inflamed and thickened, with a narrowing and plugging of the bronchial airways.Table 1 lists selected psychotropics and their potential interactions with drugs commonly taken by COPD patients.

CASE REPORT: COPD AND ANXIETY

Ms. P, age 60, is hospitalized for an exacerbation of COPD, which was diagnosed 10 years ago. She is intubated and ventilated after developing pneumonia-related respiratory failure. After a 2-week hospitalization, her pulmonologist tries to wean her off the ventilator, but episodes of panic and dyspnea result in significant oxygen desaturations.

The patient is transferred to a rehabilitation facility. A psychiatrist is consulted and discovers a 10-year history of anxiety that had been managed with lorazepam, 1 mg tid, and sertraline, 50 mg/d.

On evaluation, Ms. P is sweating, tremulous, and hyperventilating. She cannot speak, mouth words, or nod because of her respiratory distress. During her hospitalization she has been receiving albuterol and ipratropium nebulized every 4 hours; intravenous methylprednisolone, weaned from 40 mg to 10 mg every 6 hours; sertraline, 50 mg/d; clonazepam, 1 mg qid; theophylline, 400 mg/d, and several intravenous antibiotics. Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg bid, was recently added for a urinary tract infection.

Table 2

Drugs commonly used to treat COPD and their potential psychiatric side effects

| Drug | Action | Possible psychiatric side effect |

|---|---|---|

| Albuterol | Short-acting bronchodilator | Anxiety |

| Salmeterol | Long-acting bronchodilator | Anxiety, especially if used more than twice daily |

| Ipratropium | Inhaled anticholinergic | None |

| Inhaled corticosteroid (eg, fluticasone, budesonide) | Anti-inflammatory | None |

| Oral corticosteroid (prednisone, methylprednisolone) | Anti-inflammatory | Depression, anxiety, mania, delirium |

| Montelukast tablets or chewable tablets | Possibly both anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator activity | None |

| Theophylline | Anti-inflammatory and respiratory stimulant | Anxiety, especially if blood level is >20 μg/mL |

Ms. P’s mental status alternates between severe anxiety and obtundation. When her anxiety becomes acute, the attending physician prescribes intravenous lorazepam, 1 to 2 mg as needed. Her chart reveals that she has received 4 to 6 mg of lorazepam each day.

A blood test reveals a toxic theophylline level of 20 mg/mL. Acting on the psychiatrist’s suggestion, Ms. P’s physician decreases theophylline to 200 mg/d. Her anxiety improves slightly, but episodes of panic continue to block attempts to wean her from the ventilator. The psychiatrist increases sertraline to 100 mg/d and stops lorazepam. She adds gabapentin, 300 mg every 8 hours.

Within 3 days, Ms. P’s obtundation ceases and she is less tremulous and panicked. She can mouth words and answer questions by nodding. Within 1 week, her anxiety is improved. Five days later, she is weaned from the ventilator. The facility’s psychologist teaches her relaxation, visualization, and breathing exercises to counteract panic and anxiety.

Ms. P is discharged 2 weeks later, after beginning a pulmonary rehabilitation program. Her primary care physician weans her off clonazepam, and her gabapentin and sertraline dosages are continued.

Discussion. Although the estimated prevalence of anxiety among patients with COPD varies widely,10 anxiety is more prevalent in patients with severe lung disease.11

Panic attacks and anxiety in COPD have been linked to hypoxia, hypercapnia, and hypocapnia. Hyperventilation leads to a decrease in pCO2 , causing a respiratory alkalosis that leads to cerebral vasoconstriction. This ultimately results in anxiety symptoms.

Communication with other care team members is crucial to psychiatric treatment of patients with COPD. To ensure proper coordination of care:

- Medication history. Report changes in psychiatric medication to all doctors. Obtain from the primary care physician a complete list of the patient’s medications and medical problems to prevent drug-drug interactions.

- Onset of depression, anxiety. Report warning signs of depression and anxiety to other care team members, and urge doctors to refer patients who exhibit these signs. Primary care physicians often miss these potential warning signs:

- Suicidality. Alert other doctors to the warning signs of suicidality. Patients older than 65 and those with depression or chronic health problems are at increased risk of suicide. Many patients with COPD exhibit the following risk factors:

In patients with severe COPD, chronic hypoventilation increases pCO 2 levels. This has been shown in animals to activate a medullary chemoreceptor, which elicits a panic response by activating neurons in the locus ceruleus.

Lactic acid, formed because of hypoxia, is also linked to panic attacks. Investigators have postulated that persons with both panic disorder and COPD are hypersensitive to lactic acid and hyperventilation.12

In some patients, shortness of breath causes anticipatory anxiety that can further decrease activity and worsen deconditioning.

The crippling fear that comes with an anxiety or panic disorder can also complicate COPD therapy. Panic and anxiety often interfere with weaning from mechanical ventilation, despite treatment with high-dose benzodiazepines in some cases.13 The more frequent or protracted the use of ventilation, the greater the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.

COPD drugs that cause anxiety. A comprehensive review of the patient’s medications and lab readings is crucial to planning treatment. Ms. P was concomitantly taking several drugs for COPD that can cause anxiety or panic symptoms (Table 2):

- Bronchodilators such as albuterol are agonists that can increase heart rate and cause anxiety associated with rapid heartbeat.

- Theophylline, which may act as a bronchodilator and respiratory stimulant, can cause anxiety, especially at blood levels >20 mg/mL. In Ms. P’s case, the combination of ciprofloxacin and theophylline caused a CYP-450 interaction that increased her theophylline level. This is because ciprofloxacin and most other quinolone antibiotics are CYP 1A2 inducers, whereas theophylline is a CYP 1A2 substrate.9

- High-dose corticosteroids (eg, methylprednisolone) also may contribute to anxiety.

Treatment. SSRIs are an accepted first-line therapy for COPD-related anxiety. Buspirone may also work in some COPD patients. Anticonvulsants such as gabapentin and divalproex are possible adjuncts to antidepressants.

Routine use of benzodiazepines is not recommended to treat anxiety in COPD for several reasons:

- These agents can cause respiratory depression in higher doses and thus may be dangerous to patients with end-stage COPD. Reports indicate that benzodiazepines may worsen pulmonary status.14

- Rebound anxiety may occur when the drug is cleared from the system. This may accelerate benzodiazepine use, which can lead to excessively high doses and/or addiction.

Antihistamines such as hydroxyzine are a nonaddictive alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety control. They may be used as an adjunct to antidepressants if alcohol or drug addiction are present. These agents, however, may have sedating and anticholinergic side effects.

Beta blockers, commonly used to treat performance anxiety, may worsen pulmonary status and are contraindicated in COPD patients.

COPD and comorbidities. Many patients with COPD are taking several medications for comorbid hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, or congestive heart failure. These other conditions or medications may contribute to psychiatric symptoms, diminish the effectiveness of psychiatric treatment, or cause an adverse interaction with a psychotropic.

A thorough review of the patient’s medical records is strongly recommended. Communication with other care team members is critical (Box 2).

PSYCHOSOCIAL TREATMENT

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may be effective in treating COPD-related anxiety and depression. CBT involves the correction of unrealistic and harmful thought patterns (such as cat-astrophizing shortness of breath) through techniques such as guided imagery and relaxation. Breathing exercises are also used.6

Medically stable patients can be taught “interoceptive exposure” techniques by learning to induce panic symptoms in a controlled setting (such as by hyperventilating in the doctor’s office), then desensitizing themselves to the anxiety. Exposure can also be used in social settings to accustom the patient to feared stimuli.

Support groups can increase social interaction and offer a chance to discuss disease-related medical, psychological, and social issues with other COPD patients.

Pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to decrease depression and anxiety, increase functioning, and promote independence in patients with COPD.12 Patients are educated about their disease and learn breathing techniques to reduce air hunger and exercises to optimize oxygen use.

Physical exercise figures prominently in pulmonary rehabilitation by improving oxygen consumption efficiency. This in turn improves exercise tolerance.15

COPD AND DELIRIUM

Delirium is common among older patients with COPD. Two or more causes can be at work simultaneously, such as:

- hypoxia and hypercapnia

- reactions to antibiotics, antivirals, and corticosteroids used to treat COPD.

Delirium can simulate depression, anxiety, mania, and psychosis because affective lability, fluctuating levels of consciousness, and impaired reality testing are features of delirium.

A COPD patient’s sudden change in mental status should prompt a careful review of medications and medical conditions and an oxygen saturation measurement. An arterial blood gas reading may also be helpful because hypercapnia can be present without hypoxia. The sudden onset of psychotic symptoms in a patient with COPD should also prompt a thorough search for causes of delirium.16

Related resources

- Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al (eds.). Harrison’s principles of internal medicine (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing, 2001.

- American Lung Association: Around the clock with COPD. http://www.lungusa.org/diseases/copd_clock.html

- National Emphysema Foundation. http://www.emphysemafoundation.org/

Drug brand names

- Albuterol • Proventil, Ventolin

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amantadine • Symmetrel

- Atorvastatin • Lipitor

- Budesonide • Pulmicort

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Cimetidine • Tagamet

- Ciprofloxacin • Ciloxan, Cipro

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Diazepam • Valium

- Digoxin • Lanoxin

- Divalproex • Depakote

- Erythromycin • Emgel, others

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluconazole • Diflucan

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluticasone • Flovent

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Hydroxyzine • Atarax, Vistaril

- Ipratropium • Atrovent

- Itraconazole • Sporanox

- Levodopa • Sinemet

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Montelukast • Singulair

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Salmeterol • Serevent

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Simvastatin • Zocor

- Theophylline • Theo-dur, others

- Triazolam • Halcion

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Warfarin • Coumadin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: Leading causes for 2000. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2002;50(6):8.-Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs. Accessed October 16, 2003.

2. American Lung Association fact sheet: COPD. Available at: http://www.lungusa.org/diseases/copd_factsheet.html. Accessed Sept. 23, 2003.

3. American Lung Association: Breathless in America Available at: http://www.lungusa.org/press/lung_dis/asn_copd21601.html. Accessed Sept. 8, 2003.

4. Gift AG, McCrone SH. Depression in patients with COPD. Heart Lung 1993;22:289-97.

5. Light RW, Merrill EJ, Despars JA, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Chest 1985;87:35-8.

6. Dudley DL, Glaser EM, Jorgenson BN, Logan DL. Psychosocial concomitants to rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Part 2: psychosocial treatment. Chest 1980;77:544-51.

7. Wise MG, Rundell JR (eds). Textbook of consultation-liaison psychiatry: psychiatry in the medically ill. (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2002.

8. Dahlen I, Janson C. Anxiety and depression are related to the outcome of emergency treatment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2002;122:1633-7.

9. Physicians’ Desk Reference (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003.

10. Karajgi B, Rifkin A, Doddi S, Kolli R. The prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:200-1.

11. Porzelius J, Vest M, Nochomovitz M. Respiratory function, cognitions, and panic in chronic obstructive pulmonary patients. Behav Res Ther 1992;30:75-7.

12. Smoller JW, Pollack MH. Panic anxiety, dyspnea, and respiratory disease. Theoretical and clinical considerations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:6-17.

13. Mendel JG, Kahn FA. Psychosocial aspects of weaning from mechanical ventilation. Psychosomatics 1980;21:465-71.

14. Man GCW, Hsu K, Sproule BJ. Effect of alprazolam on exercise and dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 1986;90:832-6.

15. Ries AL, Kaplan RM, Limberg TM, Prewitt LM. Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on physiologic and psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:823-32.

16. Yudofsky SC, Hales RE (eds). Textbook of neuropsychiatry. (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1997;447-70.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: Leading causes for 2000. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2002;50(6):8.-Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs. Accessed October 16, 2003.

2. American Lung Association fact sheet: COPD. Available at: http://www.lungusa.org/diseases/copd_factsheet.html. Accessed Sept. 23, 2003.

3. American Lung Association: Breathless in America Available at: http://www.lungusa.org/press/lung_dis/asn_copd21601.html. Accessed Sept. 8, 2003.

4. Gift AG, McCrone SH. Depression in patients with COPD. Heart Lung 1993;22:289-97.

5. Light RW, Merrill EJ, Despars JA, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Chest 1985;87:35-8.

6. Dudley DL, Glaser EM, Jorgenson BN, Logan DL. Psychosocial concomitants to rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Part 2: psychosocial treatment. Chest 1980;77:544-51.

7. Wise MG, Rundell JR (eds). Textbook of consultation-liaison psychiatry: psychiatry in the medically ill. (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2002.

8. Dahlen I, Janson C. Anxiety and depression are related to the outcome of emergency treatment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2002;122:1633-7.

9. Physicians’ Desk Reference (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003.

10. Karajgi B, Rifkin A, Doddi S, Kolli R. The prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:200-1.

11. Porzelius J, Vest M, Nochomovitz M. Respiratory function, cognitions, and panic in chronic obstructive pulmonary patients. Behav Res Ther 1992;30:75-7.

12. Smoller JW, Pollack MH. Panic anxiety, dyspnea, and respiratory disease. Theoretical and clinical considerations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:6-17.

13. Mendel JG, Kahn FA. Psychosocial aspects of weaning from mechanical ventilation. Psychosomatics 1980;21:465-71.

14. Man GCW, Hsu K, Sproule BJ. Effect of alprazolam on exercise and dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 1986;90:832-6.

15. Ries AL, Kaplan RM, Limberg TM, Prewitt LM. Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on physiologic and psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:823-32.

16. Yudofsky SC, Hales RE (eds). Textbook of neuropsychiatry. (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1997;447-70.