User login

Cross-contamination of pathology specimens is a rare but nonnegligible source of potential morbidity in clinical practice. Contaminant tissue fragments, colloquially referred to as floaters, typically are readily identifiable based on obvious cytomorphologic differences, especially if the tissues arise from different organs; however, one cannot rely on such distinctions in a pathology laboratory dedicated to a single organ system (eg, dermatopathology). The inability to identify quickly and confidently the presence of a contaminant puts the patient at risk for misdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary morbidity or even mortality in the case of cancer misdiagnosis. Studies that have been conducted to estimate the incidence of this type of error have suggested an overall incidence rate between approximately 1% and 3%.1,2 Awareness of this phenomenon and careful scrutiny when the histopathologic evidence diverges considerably from the clinical impression is critical for minimizing the negative outcomes that could result from the presence of contaminant tissue. We present a case in which cross-contamination of a pathology specimen led to an initial erroneous diagnosis of an aggressive cutaneous melanoma in a patient with a benign adnexal neoplasm.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man was referred to the Pigmented Lesion and Melanoma Program at Stanford University Medical Center and Cancer Institute (Palo Alto, California) for evaluation and treatment of a presumed stage IIB melanoma on the right preauricular cheek based on a shave biopsy that had been performed (<1 month prior) by his local dermatology provider and subsequently read by an affiliated out-of-state dermatopathology laboratory. Per the clinical history that was gathered at the current presentation, neither the patient nor his wife had noticed the lesion prior to his dermatology provider pointing it out on the day of the biopsy. Additionally, he denied associated pain, bleeding, or ulceration. According to outside medical records, the referring dermatology provider described the lesion as a 4-mm pink pearly papule with telangiectasia favoring a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, and a diagnostic shave biopsy was performed. On presentation to our clinic, physical examination of the right preauricular cheek revealed a 4×3-mm depressed erythematous scar with no evidence of residual pigmentation or nodularity (Figure 1). There was no clinically appreciable regional lymphadenopathy.

The original dermatopathology report indicated an invasive melanoma with the following pathologic characteristics: superficial spreading type, Breslow depth of at least 2.16 mm, ulceration, and a mitotic index of 8 mitotic figures/mm2 with transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins. There was no evidence of regression, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or microsatellites. Interestingly, the report indicated that there also was a basaloid proliferation with features of cylindroma in the same pathology slide adjacent to the aggressive invasive melanoma that was described. Given the complexity of cases referred to our academic center, the standard of care includes internal dermatopathology review of all outside pathology specimens. This review proved critical to this patient’s care in light of the considerable divergence of the initial pathologic diagnosis and the reported clinical features of the lesion.

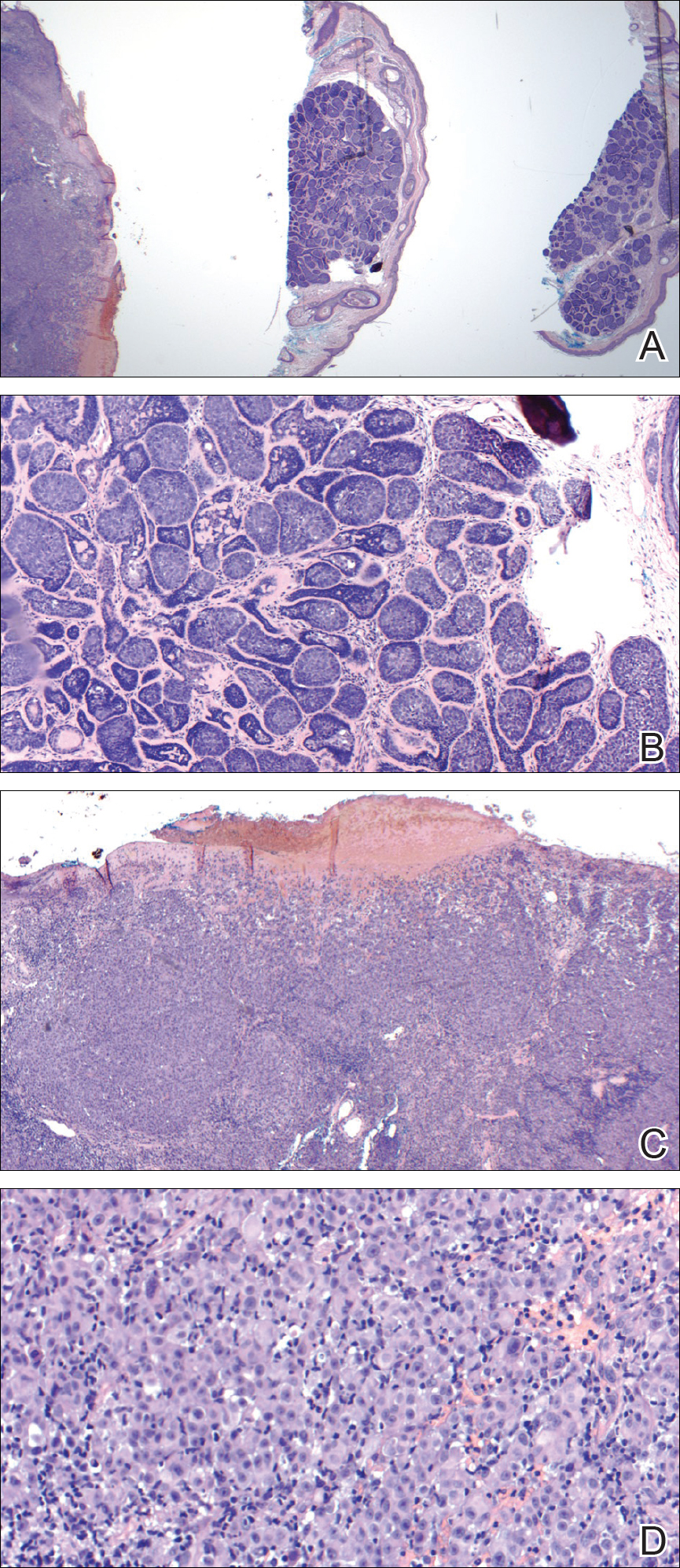

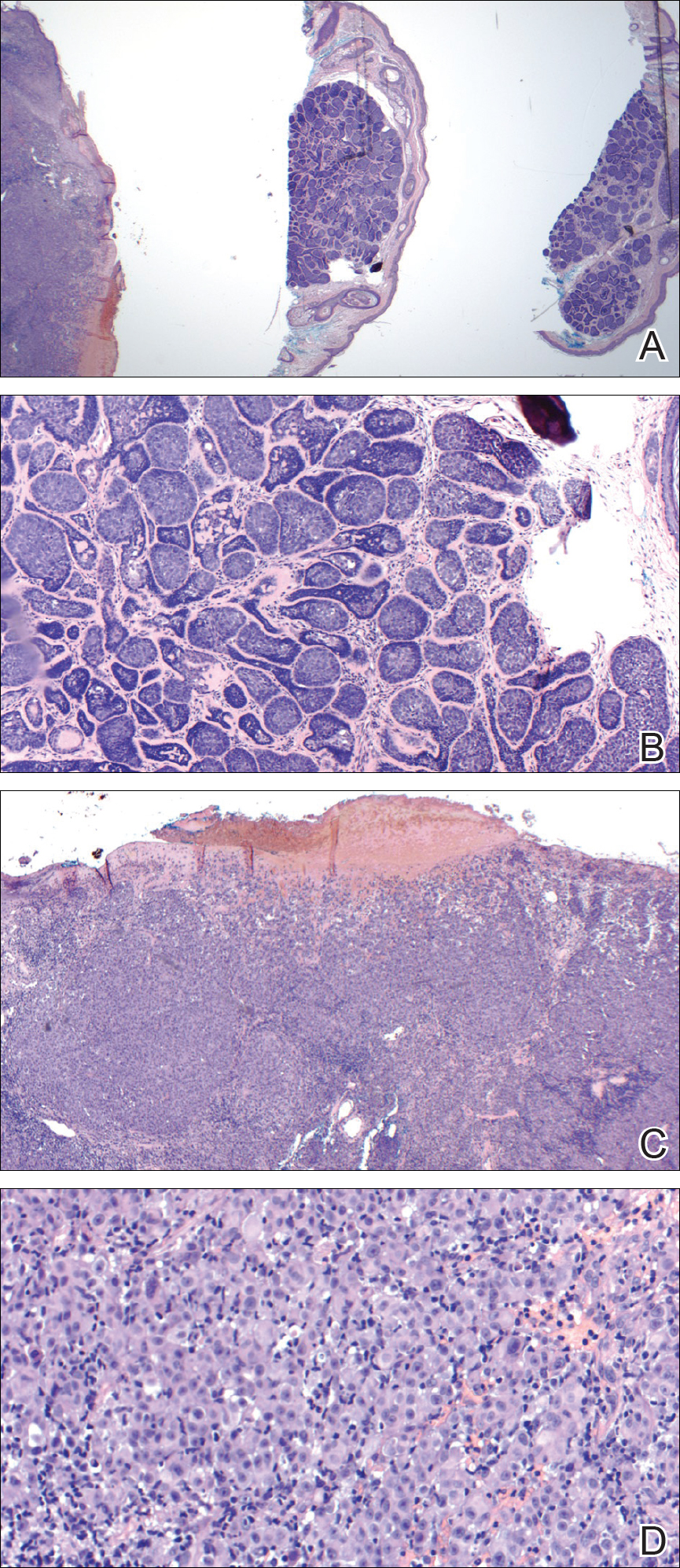

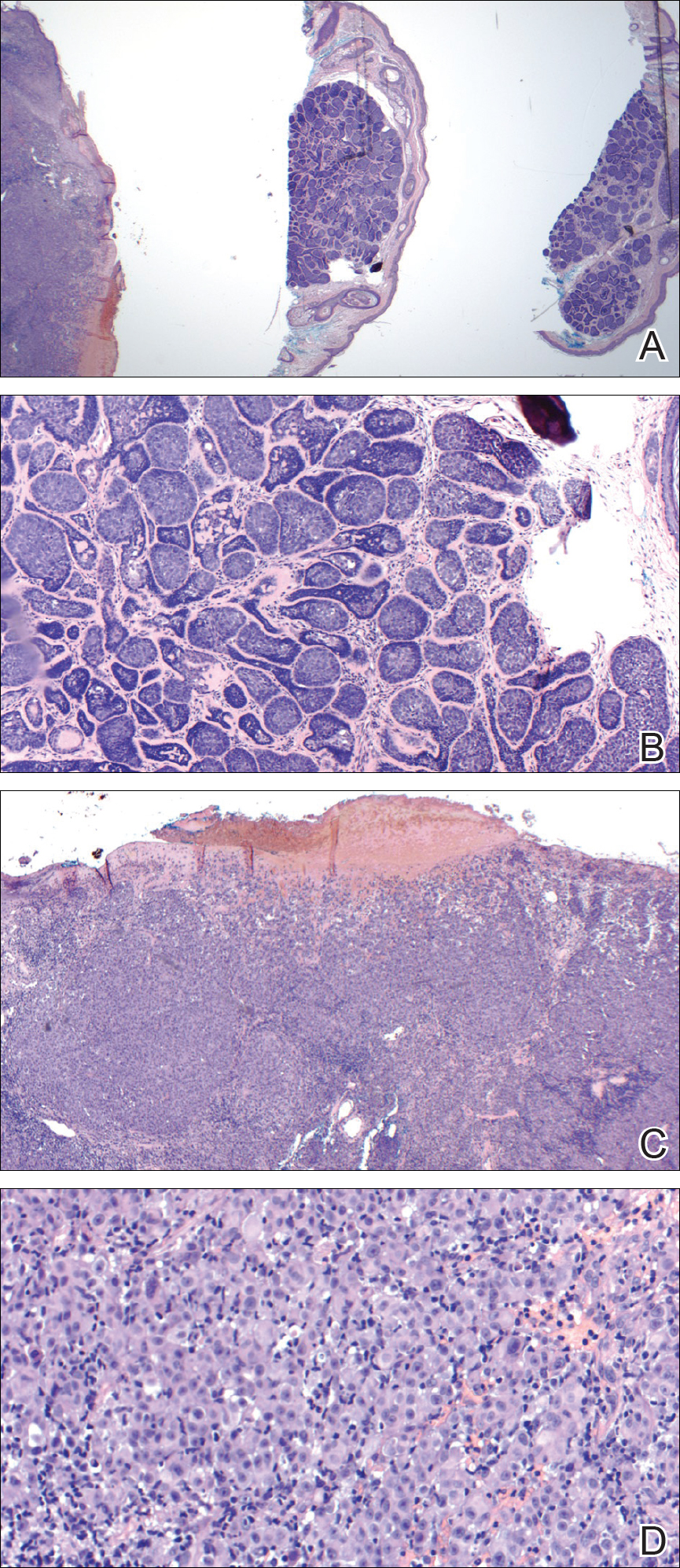

Internal review of the single pathology slide received from the referring provider showed a total of 4 sections, 3 of which are shown here (Figure 2A). Three sections, including the one not shown, were all consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma and showed no evidence of a melanocytic proliferation (Figure 2B). However, the fourth section demonstrated marked morphologic dissimilarity compared to the other 3 sections. This outlier section showed a thick cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 2.1 mm, ulceration, a mitotic rate of 12 mitotic figures/mm2, and broad transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins (Figures 2C and 2D). Correlation with the gross description of tissue processing on the original pathology report indicating that the specimen had been trisected raised suspicion that the fourth and very dissimilar section could be a contaminant from another source that was incorporated into our patient’s histologic sections during processing. Taken together, these discrepancies made the diagnosis of cylindroma alone far more likely than cutaneous melanoma, but we needed conclusive evidence given the dramatic difference in prognosis and management between a cylindroma and an aggressive cutaneous melanoma.

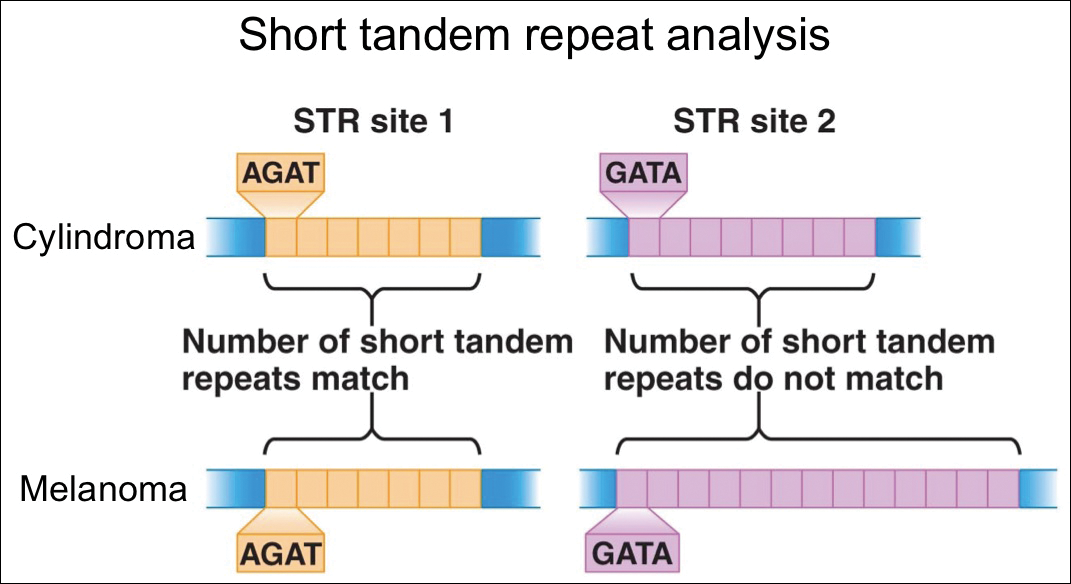

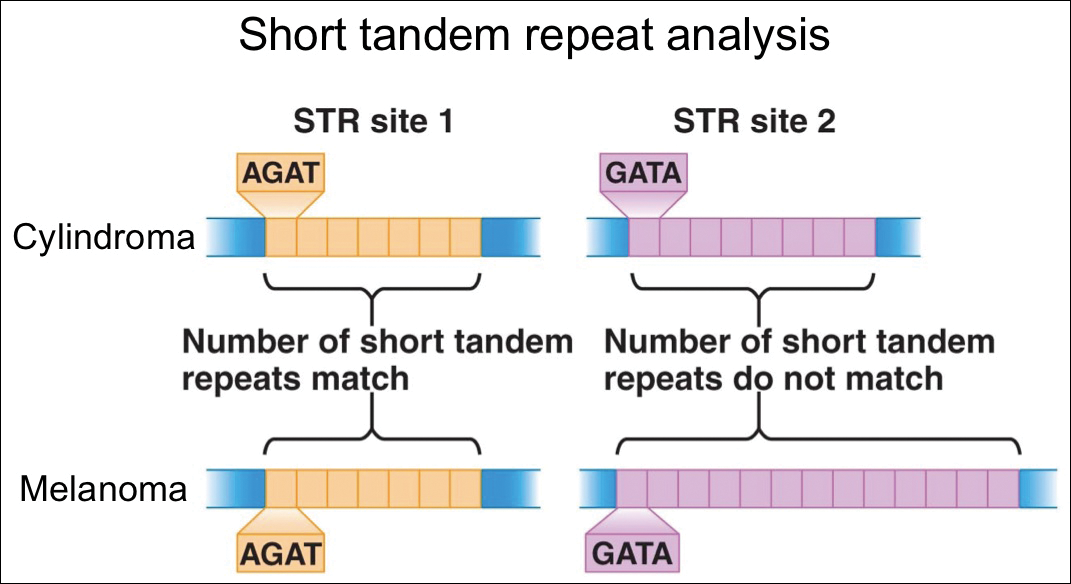

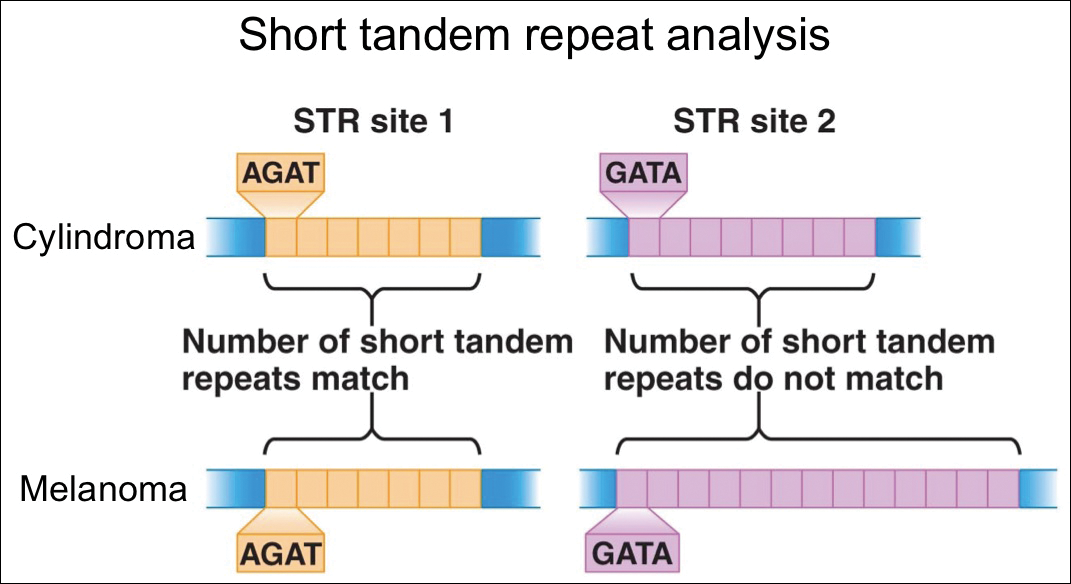

For further diagnostic clarification, we performed polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, a well-described forensic pathology technique, to determine if the melanoma and cylindroma specimens derived from different patients, as we hypothesized. This analysis revealed differences in all but one DNA locus tested between the cylindroma specimen and the melanoma specimen, confirming our hypothesis (Figure 3). Subsequent discussion of the case with staff from the dermatopathology laboratory that processed this specimen provided further support for our suspicion that the invasive melanoma specimen was part of a case processed prior to our patient’s benign lesion. Therefore, the wide local excision for treatment of the suspected melanoma fortunately was canceled, and the patient did not require further treatment of the benign cylindroma. The patient expressed relief and gratitude for this critical clarification and change in management.

Comment

Shah et al3 reported a similar case in which a benign granuloma of the lung masqueraded as a squamous cell carcinoma due to histopathologic contamination. Although few similar cases have been described in the literature, the risk posed by such contamination is remarkable, regardless of whether it occurs during specimen grossing, embedding, sectioning, or staining.1,4,5 This risk is amplified in facilities that process specimens originating predominantly from a single organ system or tissue type, as is often the case in dedicated dermatopathology laboratories. In this scenario, it is unlikely that one could use the presence of tissues from 2 different organ systems on a single slide as a way of easily recognizing the presence of a contaminant and rectifying the error. Additionally, the presence of malignant cells in the contaminant further complicates the problem and requires an investigation that can conclusively distinguish the contaminant from the patient’s actual tissue.

In our case, our dermatology and dermatopathology teams partnered with our molecular pathology team to find a solution. Polymorphic STR analysis via polymerase chain reaction amplification is a sensitive method employed commonly in forensic DNA laboratories for determining whether a sample submitted as evidence belongs to a given suspect.6 Although much more commonly used in forensics, STR analysis does have known roles in clinical medicine, such as chimerism testing after bone marrow or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.7 Given the relatively short period of time it takes along with the convenience of commercially available kits, a high discriminative ability, and well-validated interpretation procedures, STR analysis is an excellent method for determining if a given tissue sample came from a given patient, which is what was needed in our case.

The combined clinical, histopathologic, and molecular data in our case allowed for confident clarification of our patient’s diagnosis, sparing him the morbidity of wide local excision on the face, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of aggressive cutaneous melanoma. Our case highlights the critical importance of internal review of pathology specimens in ensuring proper diagnosis and management and reminds us that, though rare, accidental contamination during processing of pathology specimens is a potential adverse event that must be considered, especially when a pathologic finding diverges considerably from what is anticipated based on the patient’s history and physical examination.

Acknowledgment

The authors express gratitude to the patient described herein who graciously provided permission for us to publish his case and clinical photography.

- Gephardt GN, Zarbo RJ. Extraneous tissue in surgical pathology: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 275 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1009-1014.

- Alam M, Shah AD, Ali S, et al. Floaters in Mohs micrographic surgery [published online June 27, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1317-1322.

- Shah PA, Prat MP, Hostler DC. Benign granuloma masquerading as squamous cell carcinoma due to a “floater.” Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(11, suppl 2):19-21.

- Platt E, Sommer P, McDonald L, et al. Tissue floaters and contaminants in the histology laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:973-978.

- Layfield LJ, Witt BL, Metzger KG, et al. Extraneous tissue: a potential source for diagnostic error in surgical pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:767-772.

- Butler JM. Forensic DNA testing. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:1438-1450.

- Manasatienkij C, Ra-ngabpai C. Clinical application of forensic DNA analysis: a literature review. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:1357-1363.

Cross-contamination of pathology specimens is a rare but nonnegligible source of potential morbidity in clinical practice. Contaminant tissue fragments, colloquially referred to as floaters, typically are readily identifiable based on obvious cytomorphologic differences, especially if the tissues arise from different organs; however, one cannot rely on such distinctions in a pathology laboratory dedicated to a single organ system (eg, dermatopathology). The inability to identify quickly and confidently the presence of a contaminant puts the patient at risk for misdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary morbidity or even mortality in the case of cancer misdiagnosis. Studies that have been conducted to estimate the incidence of this type of error have suggested an overall incidence rate between approximately 1% and 3%.1,2 Awareness of this phenomenon and careful scrutiny when the histopathologic evidence diverges considerably from the clinical impression is critical for minimizing the negative outcomes that could result from the presence of contaminant tissue. We present a case in which cross-contamination of a pathology specimen led to an initial erroneous diagnosis of an aggressive cutaneous melanoma in a patient with a benign adnexal neoplasm.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man was referred to the Pigmented Lesion and Melanoma Program at Stanford University Medical Center and Cancer Institute (Palo Alto, California) for evaluation and treatment of a presumed stage IIB melanoma on the right preauricular cheek based on a shave biopsy that had been performed (<1 month prior) by his local dermatology provider and subsequently read by an affiliated out-of-state dermatopathology laboratory. Per the clinical history that was gathered at the current presentation, neither the patient nor his wife had noticed the lesion prior to his dermatology provider pointing it out on the day of the biopsy. Additionally, he denied associated pain, bleeding, or ulceration. According to outside medical records, the referring dermatology provider described the lesion as a 4-mm pink pearly papule with telangiectasia favoring a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, and a diagnostic shave biopsy was performed. On presentation to our clinic, physical examination of the right preauricular cheek revealed a 4×3-mm depressed erythematous scar with no evidence of residual pigmentation or nodularity (Figure 1). There was no clinically appreciable regional lymphadenopathy.

The original dermatopathology report indicated an invasive melanoma with the following pathologic characteristics: superficial spreading type, Breslow depth of at least 2.16 mm, ulceration, and a mitotic index of 8 mitotic figures/mm2 with transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins. There was no evidence of regression, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or microsatellites. Interestingly, the report indicated that there also was a basaloid proliferation with features of cylindroma in the same pathology slide adjacent to the aggressive invasive melanoma that was described. Given the complexity of cases referred to our academic center, the standard of care includes internal dermatopathology review of all outside pathology specimens. This review proved critical to this patient’s care in light of the considerable divergence of the initial pathologic diagnosis and the reported clinical features of the lesion.

Internal review of the single pathology slide received from the referring provider showed a total of 4 sections, 3 of which are shown here (Figure 2A). Three sections, including the one not shown, were all consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma and showed no evidence of a melanocytic proliferation (Figure 2B). However, the fourth section demonstrated marked morphologic dissimilarity compared to the other 3 sections. This outlier section showed a thick cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 2.1 mm, ulceration, a mitotic rate of 12 mitotic figures/mm2, and broad transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins (Figures 2C and 2D). Correlation with the gross description of tissue processing on the original pathology report indicating that the specimen had been trisected raised suspicion that the fourth and very dissimilar section could be a contaminant from another source that was incorporated into our patient’s histologic sections during processing. Taken together, these discrepancies made the diagnosis of cylindroma alone far more likely than cutaneous melanoma, but we needed conclusive evidence given the dramatic difference in prognosis and management between a cylindroma and an aggressive cutaneous melanoma.

For further diagnostic clarification, we performed polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, a well-described forensic pathology technique, to determine if the melanoma and cylindroma specimens derived from different patients, as we hypothesized. This analysis revealed differences in all but one DNA locus tested between the cylindroma specimen and the melanoma specimen, confirming our hypothesis (Figure 3). Subsequent discussion of the case with staff from the dermatopathology laboratory that processed this specimen provided further support for our suspicion that the invasive melanoma specimen was part of a case processed prior to our patient’s benign lesion. Therefore, the wide local excision for treatment of the suspected melanoma fortunately was canceled, and the patient did not require further treatment of the benign cylindroma. The patient expressed relief and gratitude for this critical clarification and change in management.

Comment

Shah et al3 reported a similar case in which a benign granuloma of the lung masqueraded as a squamous cell carcinoma due to histopathologic contamination. Although few similar cases have been described in the literature, the risk posed by such contamination is remarkable, regardless of whether it occurs during specimen grossing, embedding, sectioning, or staining.1,4,5 This risk is amplified in facilities that process specimens originating predominantly from a single organ system or tissue type, as is often the case in dedicated dermatopathology laboratories. In this scenario, it is unlikely that one could use the presence of tissues from 2 different organ systems on a single slide as a way of easily recognizing the presence of a contaminant and rectifying the error. Additionally, the presence of malignant cells in the contaminant further complicates the problem and requires an investigation that can conclusively distinguish the contaminant from the patient’s actual tissue.

In our case, our dermatology and dermatopathology teams partnered with our molecular pathology team to find a solution. Polymorphic STR analysis via polymerase chain reaction amplification is a sensitive method employed commonly in forensic DNA laboratories for determining whether a sample submitted as evidence belongs to a given suspect.6 Although much more commonly used in forensics, STR analysis does have known roles in clinical medicine, such as chimerism testing after bone marrow or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.7 Given the relatively short period of time it takes along with the convenience of commercially available kits, a high discriminative ability, and well-validated interpretation procedures, STR analysis is an excellent method for determining if a given tissue sample came from a given patient, which is what was needed in our case.

The combined clinical, histopathologic, and molecular data in our case allowed for confident clarification of our patient’s diagnosis, sparing him the morbidity of wide local excision on the face, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of aggressive cutaneous melanoma. Our case highlights the critical importance of internal review of pathology specimens in ensuring proper diagnosis and management and reminds us that, though rare, accidental contamination during processing of pathology specimens is a potential adverse event that must be considered, especially when a pathologic finding diverges considerably from what is anticipated based on the patient’s history and physical examination.

Acknowledgment

The authors express gratitude to the patient described herein who graciously provided permission for us to publish his case and clinical photography.

Cross-contamination of pathology specimens is a rare but nonnegligible source of potential morbidity in clinical practice. Contaminant tissue fragments, colloquially referred to as floaters, typically are readily identifiable based on obvious cytomorphologic differences, especially if the tissues arise from different organs; however, one cannot rely on such distinctions in a pathology laboratory dedicated to a single organ system (eg, dermatopathology). The inability to identify quickly and confidently the presence of a contaminant puts the patient at risk for misdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary morbidity or even mortality in the case of cancer misdiagnosis. Studies that have been conducted to estimate the incidence of this type of error have suggested an overall incidence rate between approximately 1% and 3%.1,2 Awareness of this phenomenon and careful scrutiny when the histopathologic evidence diverges considerably from the clinical impression is critical for minimizing the negative outcomes that could result from the presence of contaminant tissue. We present a case in which cross-contamination of a pathology specimen led to an initial erroneous diagnosis of an aggressive cutaneous melanoma in a patient with a benign adnexal neoplasm.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man was referred to the Pigmented Lesion and Melanoma Program at Stanford University Medical Center and Cancer Institute (Palo Alto, California) for evaluation and treatment of a presumed stage IIB melanoma on the right preauricular cheek based on a shave biopsy that had been performed (<1 month prior) by his local dermatology provider and subsequently read by an affiliated out-of-state dermatopathology laboratory. Per the clinical history that was gathered at the current presentation, neither the patient nor his wife had noticed the lesion prior to his dermatology provider pointing it out on the day of the biopsy. Additionally, he denied associated pain, bleeding, or ulceration. According to outside medical records, the referring dermatology provider described the lesion as a 4-mm pink pearly papule with telangiectasia favoring a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, and a diagnostic shave biopsy was performed. On presentation to our clinic, physical examination of the right preauricular cheek revealed a 4×3-mm depressed erythematous scar with no evidence of residual pigmentation or nodularity (Figure 1). There was no clinically appreciable regional lymphadenopathy.

The original dermatopathology report indicated an invasive melanoma with the following pathologic characteristics: superficial spreading type, Breslow depth of at least 2.16 mm, ulceration, and a mitotic index of 8 mitotic figures/mm2 with transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins. There was no evidence of regression, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or microsatellites. Interestingly, the report indicated that there also was a basaloid proliferation with features of cylindroma in the same pathology slide adjacent to the aggressive invasive melanoma that was described. Given the complexity of cases referred to our academic center, the standard of care includes internal dermatopathology review of all outside pathology specimens. This review proved critical to this patient’s care in light of the considerable divergence of the initial pathologic diagnosis and the reported clinical features of the lesion.

Internal review of the single pathology slide received from the referring provider showed a total of 4 sections, 3 of which are shown here (Figure 2A). Three sections, including the one not shown, were all consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma and showed no evidence of a melanocytic proliferation (Figure 2B). However, the fourth section demonstrated marked morphologic dissimilarity compared to the other 3 sections. This outlier section showed a thick cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 2.1 mm, ulceration, a mitotic rate of 12 mitotic figures/mm2, and broad transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins (Figures 2C and 2D). Correlation with the gross description of tissue processing on the original pathology report indicating that the specimen had been trisected raised suspicion that the fourth and very dissimilar section could be a contaminant from another source that was incorporated into our patient’s histologic sections during processing. Taken together, these discrepancies made the diagnosis of cylindroma alone far more likely than cutaneous melanoma, but we needed conclusive evidence given the dramatic difference in prognosis and management between a cylindroma and an aggressive cutaneous melanoma.

For further diagnostic clarification, we performed polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, a well-described forensic pathology technique, to determine if the melanoma and cylindroma specimens derived from different patients, as we hypothesized. This analysis revealed differences in all but one DNA locus tested between the cylindroma specimen and the melanoma specimen, confirming our hypothesis (Figure 3). Subsequent discussion of the case with staff from the dermatopathology laboratory that processed this specimen provided further support for our suspicion that the invasive melanoma specimen was part of a case processed prior to our patient’s benign lesion. Therefore, the wide local excision for treatment of the suspected melanoma fortunately was canceled, and the patient did not require further treatment of the benign cylindroma. The patient expressed relief and gratitude for this critical clarification and change in management.

Comment

Shah et al3 reported a similar case in which a benign granuloma of the lung masqueraded as a squamous cell carcinoma due to histopathologic contamination. Although few similar cases have been described in the literature, the risk posed by such contamination is remarkable, regardless of whether it occurs during specimen grossing, embedding, sectioning, or staining.1,4,5 This risk is amplified in facilities that process specimens originating predominantly from a single organ system or tissue type, as is often the case in dedicated dermatopathology laboratories. In this scenario, it is unlikely that one could use the presence of tissues from 2 different organ systems on a single slide as a way of easily recognizing the presence of a contaminant and rectifying the error. Additionally, the presence of malignant cells in the contaminant further complicates the problem and requires an investigation that can conclusively distinguish the contaminant from the patient’s actual tissue.

In our case, our dermatology and dermatopathology teams partnered with our molecular pathology team to find a solution. Polymorphic STR analysis via polymerase chain reaction amplification is a sensitive method employed commonly in forensic DNA laboratories for determining whether a sample submitted as evidence belongs to a given suspect.6 Although much more commonly used in forensics, STR analysis does have known roles in clinical medicine, such as chimerism testing after bone marrow or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.7 Given the relatively short period of time it takes along with the convenience of commercially available kits, a high discriminative ability, and well-validated interpretation procedures, STR analysis is an excellent method for determining if a given tissue sample came from a given patient, which is what was needed in our case.

The combined clinical, histopathologic, and molecular data in our case allowed for confident clarification of our patient’s diagnosis, sparing him the morbidity of wide local excision on the face, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of aggressive cutaneous melanoma. Our case highlights the critical importance of internal review of pathology specimens in ensuring proper diagnosis and management and reminds us that, though rare, accidental contamination during processing of pathology specimens is a potential adverse event that must be considered, especially when a pathologic finding diverges considerably from what is anticipated based on the patient’s history and physical examination.

Acknowledgment

The authors express gratitude to the patient described herein who graciously provided permission for us to publish his case and clinical photography.

- Gephardt GN, Zarbo RJ. Extraneous tissue in surgical pathology: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 275 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1009-1014.

- Alam M, Shah AD, Ali S, et al. Floaters in Mohs micrographic surgery [published online June 27, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1317-1322.

- Shah PA, Prat MP, Hostler DC. Benign granuloma masquerading as squamous cell carcinoma due to a “floater.” Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(11, suppl 2):19-21.

- Platt E, Sommer P, McDonald L, et al. Tissue floaters and contaminants in the histology laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:973-978.

- Layfield LJ, Witt BL, Metzger KG, et al. Extraneous tissue: a potential source for diagnostic error in surgical pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:767-772.

- Butler JM. Forensic DNA testing. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:1438-1450.

- Manasatienkij C, Ra-ngabpai C. Clinical application of forensic DNA analysis: a literature review. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:1357-1363.

- Gephardt GN, Zarbo RJ. Extraneous tissue in surgical pathology: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 275 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1009-1014.

- Alam M, Shah AD, Ali S, et al. Floaters in Mohs micrographic surgery [published online June 27, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1317-1322.

- Shah PA, Prat MP, Hostler DC. Benign granuloma masquerading as squamous cell carcinoma due to a “floater.” Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(11, suppl 2):19-21.

- Platt E, Sommer P, McDonald L, et al. Tissue floaters and contaminants in the histology laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:973-978.

- Layfield LJ, Witt BL, Metzger KG, et al. Extraneous tissue: a potential source for diagnostic error in surgical pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:767-772.

- Butler JM. Forensic DNA testing. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:1438-1450.

- Manasatienkij C, Ra-ngabpai C. Clinical application of forensic DNA analysis: a literature review. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:1357-1363.

Resident Pearl

- Although cross-contamination of pathology specimens is rare, it does occur and can impact diagnosis and management if detected early.