User login

Take-Home Points

- Hip capsule provides static stabilization for the hip joint.

- Capsular management must weigh visualization to address underlying osseous deformity but also repair/plication of the capsule to maintain biomechanical characteristics.

- T-capsulotomy provides optimal visualization with a small interportal incision with a vertical incision along the femoral neck.

- Extensile interportal capsulotomy is the most widely used capsulotomy and size may vary depending on capsular and patient characteristics.

- Orthopedic surgeons should be equipped to employ either technique depending on the patients individual hip pathomorphology.

Hip arthroscopy has emerged as a common surgical treatment for a number of hip pathologies. Surgical treatment strategies, including management of the hip capsule, have evolved. Whereas earlier hip arthroscopies often involved capsulectomy or capsulotomy without repair, more recently capsular closure has been considered an important step in restoring the anatomy of the hip joint and preventing microinstability or gross macroinstability.

The anatomy of the hip joint includes both static and dynamic stabilizers designed to maintain a functioning articulation. The osseous articulation of the femoral head and acetabulum is the first static stabilizer, with variations in offset, version, and inclination of the acetabulum and the proximal femur. The joint capsule consists of 3 ligaments—iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral—that converge to form the zona orbicularis. Other soft-tissue structures, such as the articular cartilage, the labrum, the transverse acetabular ligament, the pulvinar, and the ligamentum teres, also provide static constraint.1 The surrounding musculature provides the hip joint with dynamic stability, which contributes to overall maintenance of proper joint kinematics.

Management of the hip capsule has evolved as our understanding of hip pathology and biomechanics has matured. Initial articles on using hip arthroscopy to treat labral tears described improvement in clinical outcomes,2 but the cases involved limited focal capsulotomy. Not until the idea of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) was introduced were extensive capsulotomies and capsulectomies performed to address the underlying osseous deformities and emulate open techniques. Soon after our ability to access osseous pathomorphology improved with enhanced visualization and comprehensive resection, cases of hip instability after hip arthroscopy surfaced.3-5 Although frank dislocation after hip arthroscopy is rare and largely underreported, it is a catastrophic complication. In addition, focal capsular defects were also described in cases of failed hip arthroscopy and thought to lead to microinstability of the hip.6 Iatrogenic microinstability is thought to be more common, but it is also underrecognized as a cause of failure of hip arthroscopy.7Microinstability is a pathologic condition that can affect hip function. In cases of recurrent pain and unimproved functional status after surgery, microinstability should be considered. In an imaging study of capsule integrity, McCormick and colleagues6 found that 78% of patients who underwent revision arthroscopic surgery after hip arthroscopic surgery for FAI showed evidence of capsular and iliofemoral defects on magnetic resonance angiography. Frank and colleagues8 reported that, though all patients showed preoperative-to-postoperative improvement on outcome measures, those who underwent complete repair of their T-capsulotomy (vs repair of only its longitudinal portion) had superior outcomes, particularly increased sport-specific activity.

For patients undergoing hip arthroscopy, several predisposing factors can increase the risk of postoperative instability. Patient-related hip instability factors include generalized ligamentous laxity, supraphysiologic athletics (eg, dance), and borderline or true hip dysplasia. Surgeon-related factors include overaggressive acetabular rim resection, excessive labral débridement, and lack of capsular repair.5,9 Although there are multiple techniques for accessing the hip joint and addressing capsular closure at the end of surgery,9-14 we think capsular closure is an important aspect of the case.

Surgical Technique

For a demonstration of this technique, click here to see the video that accompanies this article. The patient is moved to a traction table and placed in the supine position. Induction of general anesthesia with muscle relaxation allows for atraumatic axial traction. The anesthetized patient is assessed for passive motion and ligamentous laxity. Well-padded boots are applied, and a well-padded perineal post is used for positioning. Gentle traction is applied to the contralateral limb, and axial traction is applied through the surgical limb with the hip abducted and minimally flexed. The leg is then adducted and neutrally extended, inducing a transverse vector cantilever moment to the proximal femur. The foot is internally rotated to optimize femoral neck length on an anteroposterior radiograph. The circulating nursing staff notes the onset of hip distraction in order to ensure safe traction duration.

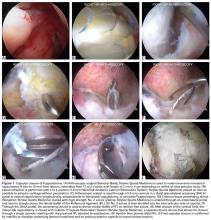

Bony landmarks are marked with a sterile marking pen. Under fluoroscopic guidance, an anterolateral (AL) portal is established 1 cm proximal and 1 cm anterior to the AL tip of the greater trochanter. Standard cannulation allows for intra-articular visualization with a 70° arthroscope. A needle is used to localize placement of a modified anterior portal. After cannulation, the arthroscope is placed in the modified anterior portal to confirm safe entry of the portal without labral violation. An arthroscopic scalpel (Samurai Blade; Stryker Sports Medicine) is used to make a transverse interportal capsulotomy 8 mm to 10 mm from the labrum and extending from 12 to 2 o’clock; length is 2 cm to 4 cm, depending on the extent of the intra-articular injury (Figure 1A).

The acetabular rim is trimmed with a 5.0-mm arthroscopic burr. Distal AL accessory (DALA) portal placement (4-6 cm distal to and in line with the AL portal) allows for suture anchor–based labral refixation. Generally, 2 to 4 anchors (1.4-mm NanoTack Anatomic Labrum Restoration System; Stryker Sports Medicine) are placed as near the articular cartilage as possible without penetration (Figure 1B). On completion of labral refixation, traction is released, and the hip is flexed to 20° to 30°.

T-Capsulotomy

Pericapsular fatty tissue is débrided with an arthroscopic shaver to visualize the interval between the iliocapsularis and gluteus minimus muscles. An arthroscopic scalpel is used, through a 5.0-mm cannula in the DALA portal, to extend the capsulotomy longitudinally and perpendicular to the interportal capsulotomy (Figure 1C). The T-capsulotomy is performed along the length of the femoral neck distally to the capsular reflection at the intertrochanteric line. The arthroscopic burr is used to perform a femoral osteochondroplasty between the lateral synovial folds (12 o’clock) and the medial synovial folds (6 o’clock). Dynamic examination and fluoroscopic imaging confirm that the entire cam deformity has been excised and that there is no evidence of impingement.

Although various suture-shuttling or tissue-penetrating/retrieving devices may be used, we recommend whichever device is appropriate for closing the capsule in its entirety. With the arthroscope in the modified anterior portal, an 8.25-mm × 90-mm cannula is placed in the AL portal, and an 8.25-mm × 110-mm cannula in the DALA portal. These portals will facilitate suture passage.

The vertical limb of the T-capsulotomy is closed with 2 to 4 side-to-side sutures, and the interportal capsulotomy limb with 2 or 3 sutures. Capsular closure begins with the distal portion of the longitudinal limb at the base of the iliofemoral ligament (IFL). A crescent tissue penetrating device (Slingshot; Stryker Sports Medicine) is loaded with high-strength No. 2 suture (Zipline; Stryker Sports Medicine) and placed through the AL portal to sharply pierce the lateral leaflet of the IFL (Figure 1D). The No. 2 suture is shuttled into the intra-articular side of the capsule (Figure 1E). Through the DALA portal, the penetrating device is used to pierce the medial leaflet to retrieve the free suture (Figure 1F). Next, the looped suture retriever is used to pull the suture from the AL portal to the DALA portal so the suture can be tied. We prefer to tie each suture individually after it is passed, but all of the sutures can be passed first, and then tied. As successive suture placement and knot tying inherently tighten the capsule, successive visualization requires more precision. Each subsequent suture is similarly passed, about 1 cm proximal to the previous stitch.

After closure of the vertical limb of the T-capsulotomy, we prefer to close the interportal capsulotomy with the InJector II Capsule Restoration System (Stryker Sports Medicine), a device that allows for closure through a single cannula lateral to medial. This device is passed through the AL cannula in order to bring the suture end through the proximal IFL attached to the acetabulum (Figure 1G). The device is removed from the cannula, and the other suture end is placed in the device and passed through the distal IFL (Figure 1H). The stitch is then tensioned and tied. Likewise, closure of the medial IFL involves passing the InJector through the DALA cannula and bringing the first suture end through the proximal IFL attached to the acetabulum. The Injector is removed from the cannula, and the other suture end is placed in the device and passed through the distal IFL. The stitch is then tensioned and tied with the hip in neutral extension. Generally, 2 or 3 stitches are used to close the interportal capsulotomy. Complete capsular closure is confirmed by the inability to visualize the underlying femoral head/neck and by probing the anterior capsule to ensure proper tension (Figure 1I).

Extensile Interportal Capsulotomy

An alternative to T-capsulotomy is interportal capsulotomy. Just as with T-capsulotomy closure, multiple different suture passing devices can be used. Good visualization for accessing the peripheral compartment generally is achieved by making the interportal capsulotomy 4 cm to 6 cm longer than the horizontal limb of the T-capsulotomy (Figures 2A, 2B). Capsular closure usually begins with the medial portion of the interportal capsulotomy. With the arthroscope in the AL portal, the 8.25-mm × 90-mm cannula is placed in the midanterior portal (MAP), and an 8.25-mm × 110-mm cannula is placed in the DALA portal.

Ligamentous laxity determines degree of capsular closure. The capsular leaflets can be closed end to end if there is little concern for laxity and instability. If there is more concern for capsular laxity, a larger bite of the capsular tissue can be taken to allow for a greater degree of plication. Further, the interportal capsule can be tightened by alternately advancing the location where sutures are passed through the capsule. Specifically, the sutures are passed such that larger bites of the distal capsule are taken, increasing the tightness of the capsule in external rotation.9

Rehabilitation

After surgery, hip extension and external rotation are limited to decrease stress on the capsular closure. The patient is placed into a hip orthosis with 0° to 90° of flexion and a night abduction pillow to limit hip external rotation. Crutch-assisted gait with 20 lb of foot-flat weight-bearing is maintained the first 3 weeks. Continuous passive motion and use of a stationary bicycle are recommended for the first 3 weeks, and then the patient slowly progresses to muscle strengthening, including core and proximal motor control. Closed-chain exercises are begun 6 weeks after surgery. Treadmill running may start at 12 weeks, with the goal of returning to sport at 4 to 6 months.

Discussion

Capsular closure during hip arthroscopy restores the normal anatomy of the IFL and therefore restores the biomechanical characteristics of the hip joint. Scientific studies have found that capsular repair or plication after hip arthroscopy restores normal hip translation, rotation, and strain. Clinical studies have also demonstrated a lower revision rate and more rapid return to athletic activity. Capsular closure, however, is technically challenging and increases operative time, but gross instability and microinstability can be avoided with meticulous closure/plication.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):49-54. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Boykin RE, Anz AW, Bushnell BD, Kocher MS, Stubbs AJ, Philippon MJ. Hip instability. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(6):340-349.

2. Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy for labral pathology: prospective analysis with 10-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):365-368.

3. Benali Y, Katthagen BD. Hip subluxation as a complication of arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):405-407.

4. Matsuda DK. Acute iatrogenic dislocation following hip impingement arthroscopic surgery. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):400-404.

5. Ranawat AS, McClincy M, Sekiya JK. Anterior dislocation of the hip after arthroscopy in a patient with capsular laxity of the hip. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):192-197.

6. McCormick F, Slikker W 3rd, Harris JD, et al. Evidence of capsular defect following hip arthroscopy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):902-905.

7. Wylie JD, Beckmann JT, Maak TG, Aoki SK. Arthroscopic capsular repair for symptomatic hip instability after previous hip arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(1):39-45.

8. Frank RM, Lee S, Bush-Joseph CA, Kelly BT, Salata MJ, Nho SJ. Improved outcomes after hip arthroscopic surgery in patients undergoing T-capsulotomy with complete repair versus partial repair for femoroacetabular impingement: a comparative matched-pair analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(11):2634-2642.

9. Domb BG, Philippon MJ, Giordano BD. Arthroscopic capsulotomy, capsular repair, and capsular plication of the hip: relation to atraumatic instability. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(1):162-173.

10. Asopa V, Singh PJ. The intracapsular atraumatic arthroscopic technique for closure of the hip capsule. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(2):e245-e247.

11. Camp CL, Reardon PJ, Levy BA, Krych AJ. A simple technique for capsular repair after hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(6):e737-e740.

12. Chow RM, Engasser WM, Krych AJ, Levy BA. Arthroscopic capsular repair in the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(1):e27-e30.

13. Harris JD, Slikker W 3rd, Gupta AK, McCormick FM, Nho SJ. Routine complete capsular closure during hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(2):e89-e94.

14. Kuhns BD, Weber AE, Levy DM, et al. Capsular management in hip arthroscopy: an anatomic, biomechanical, and technical review. Front Surg. 2016;3:13.

Take-Home Points

- Hip capsule provides static stabilization for the hip joint.

- Capsular management must weigh visualization to address underlying osseous deformity but also repair/plication of the capsule to maintain biomechanical characteristics.

- T-capsulotomy provides optimal visualization with a small interportal incision with a vertical incision along the femoral neck.

- Extensile interportal capsulotomy is the most widely used capsulotomy and size may vary depending on capsular and patient characteristics.

- Orthopedic surgeons should be equipped to employ either technique depending on the patients individual hip pathomorphology.

Hip arthroscopy has emerged as a common surgical treatment for a number of hip pathologies. Surgical treatment strategies, including management of the hip capsule, have evolved. Whereas earlier hip arthroscopies often involved capsulectomy or capsulotomy without repair, more recently capsular closure has been considered an important step in restoring the anatomy of the hip joint and preventing microinstability or gross macroinstability.

The anatomy of the hip joint includes both static and dynamic stabilizers designed to maintain a functioning articulation. The osseous articulation of the femoral head and acetabulum is the first static stabilizer, with variations in offset, version, and inclination of the acetabulum and the proximal femur. The joint capsule consists of 3 ligaments—iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral—that converge to form the zona orbicularis. Other soft-tissue structures, such as the articular cartilage, the labrum, the transverse acetabular ligament, the pulvinar, and the ligamentum teres, also provide static constraint.1 The surrounding musculature provides the hip joint with dynamic stability, which contributes to overall maintenance of proper joint kinematics.

Management of the hip capsule has evolved as our understanding of hip pathology and biomechanics has matured. Initial articles on using hip arthroscopy to treat labral tears described improvement in clinical outcomes,2 but the cases involved limited focal capsulotomy. Not until the idea of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) was introduced were extensive capsulotomies and capsulectomies performed to address the underlying osseous deformities and emulate open techniques. Soon after our ability to access osseous pathomorphology improved with enhanced visualization and comprehensive resection, cases of hip instability after hip arthroscopy surfaced.3-5 Although frank dislocation after hip arthroscopy is rare and largely underreported, it is a catastrophic complication. In addition, focal capsular defects were also described in cases of failed hip arthroscopy and thought to lead to microinstability of the hip.6 Iatrogenic microinstability is thought to be more common, but it is also underrecognized as a cause of failure of hip arthroscopy.7Microinstability is a pathologic condition that can affect hip function. In cases of recurrent pain and unimproved functional status after surgery, microinstability should be considered. In an imaging study of capsule integrity, McCormick and colleagues6 found that 78% of patients who underwent revision arthroscopic surgery after hip arthroscopic surgery for FAI showed evidence of capsular and iliofemoral defects on magnetic resonance angiography. Frank and colleagues8 reported that, though all patients showed preoperative-to-postoperative improvement on outcome measures, those who underwent complete repair of their T-capsulotomy (vs repair of only its longitudinal portion) had superior outcomes, particularly increased sport-specific activity.

For patients undergoing hip arthroscopy, several predisposing factors can increase the risk of postoperative instability. Patient-related hip instability factors include generalized ligamentous laxity, supraphysiologic athletics (eg, dance), and borderline or true hip dysplasia. Surgeon-related factors include overaggressive acetabular rim resection, excessive labral débridement, and lack of capsular repair.5,9 Although there are multiple techniques for accessing the hip joint and addressing capsular closure at the end of surgery,9-14 we think capsular closure is an important aspect of the case.

Surgical Technique

For a demonstration of this technique, click here to see the video that accompanies this article. The patient is moved to a traction table and placed in the supine position. Induction of general anesthesia with muscle relaxation allows for atraumatic axial traction. The anesthetized patient is assessed for passive motion and ligamentous laxity. Well-padded boots are applied, and a well-padded perineal post is used for positioning. Gentle traction is applied to the contralateral limb, and axial traction is applied through the surgical limb with the hip abducted and minimally flexed. The leg is then adducted and neutrally extended, inducing a transverse vector cantilever moment to the proximal femur. The foot is internally rotated to optimize femoral neck length on an anteroposterior radiograph. The circulating nursing staff notes the onset of hip distraction in order to ensure safe traction duration.

Bony landmarks are marked with a sterile marking pen. Under fluoroscopic guidance, an anterolateral (AL) portal is established 1 cm proximal and 1 cm anterior to the AL tip of the greater trochanter. Standard cannulation allows for intra-articular visualization with a 70° arthroscope. A needle is used to localize placement of a modified anterior portal. After cannulation, the arthroscope is placed in the modified anterior portal to confirm safe entry of the portal without labral violation. An arthroscopic scalpel (Samurai Blade; Stryker Sports Medicine) is used to make a transverse interportal capsulotomy 8 mm to 10 mm from the labrum and extending from 12 to 2 o’clock; length is 2 cm to 4 cm, depending on the extent of the intra-articular injury (Figure 1A).

The acetabular rim is trimmed with a 5.0-mm arthroscopic burr. Distal AL accessory (DALA) portal placement (4-6 cm distal to and in line with the AL portal) allows for suture anchor–based labral refixation. Generally, 2 to 4 anchors (1.4-mm NanoTack Anatomic Labrum Restoration System; Stryker Sports Medicine) are placed as near the articular cartilage as possible without penetration (Figure 1B). On completion of labral refixation, traction is released, and the hip is flexed to 20° to 30°.

T-Capsulotomy

Pericapsular fatty tissue is débrided with an arthroscopic shaver to visualize the interval between the iliocapsularis and gluteus minimus muscles. An arthroscopic scalpel is used, through a 5.0-mm cannula in the DALA portal, to extend the capsulotomy longitudinally and perpendicular to the interportal capsulotomy (Figure 1C). The T-capsulotomy is performed along the length of the femoral neck distally to the capsular reflection at the intertrochanteric line. The arthroscopic burr is used to perform a femoral osteochondroplasty between the lateral synovial folds (12 o’clock) and the medial synovial folds (6 o’clock). Dynamic examination and fluoroscopic imaging confirm that the entire cam deformity has been excised and that there is no evidence of impingement.

Although various suture-shuttling or tissue-penetrating/retrieving devices may be used, we recommend whichever device is appropriate for closing the capsule in its entirety. With the arthroscope in the modified anterior portal, an 8.25-mm × 90-mm cannula is placed in the AL portal, and an 8.25-mm × 110-mm cannula in the DALA portal. These portals will facilitate suture passage.

The vertical limb of the T-capsulotomy is closed with 2 to 4 side-to-side sutures, and the interportal capsulotomy limb with 2 or 3 sutures. Capsular closure begins with the distal portion of the longitudinal limb at the base of the iliofemoral ligament (IFL). A crescent tissue penetrating device (Slingshot; Stryker Sports Medicine) is loaded with high-strength No. 2 suture (Zipline; Stryker Sports Medicine) and placed through the AL portal to sharply pierce the lateral leaflet of the IFL (Figure 1D). The No. 2 suture is shuttled into the intra-articular side of the capsule (Figure 1E). Through the DALA portal, the penetrating device is used to pierce the medial leaflet to retrieve the free suture (Figure 1F). Next, the looped suture retriever is used to pull the suture from the AL portal to the DALA portal so the suture can be tied. We prefer to tie each suture individually after it is passed, but all of the sutures can be passed first, and then tied. As successive suture placement and knot tying inherently tighten the capsule, successive visualization requires more precision. Each subsequent suture is similarly passed, about 1 cm proximal to the previous stitch.

After closure of the vertical limb of the T-capsulotomy, we prefer to close the interportal capsulotomy with the InJector II Capsule Restoration System (Stryker Sports Medicine), a device that allows for closure through a single cannula lateral to medial. This device is passed through the AL cannula in order to bring the suture end through the proximal IFL attached to the acetabulum (Figure 1G). The device is removed from the cannula, and the other suture end is placed in the device and passed through the distal IFL (Figure 1H). The stitch is then tensioned and tied. Likewise, closure of the medial IFL involves passing the InJector through the DALA cannula and bringing the first suture end through the proximal IFL attached to the acetabulum. The Injector is removed from the cannula, and the other suture end is placed in the device and passed through the distal IFL. The stitch is then tensioned and tied with the hip in neutral extension. Generally, 2 or 3 stitches are used to close the interportal capsulotomy. Complete capsular closure is confirmed by the inability to visualize the underlying femoral head/neck and by probing the anterior capsule to ensure proper tension (Figure 1I).

Extensile Interportal Capsulotomy

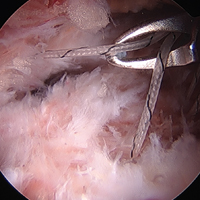

An alternative to T-capsulotomy is interportal capsulotomy. Just as with T-capsulotomy closure, multiple different suture passing devices can be used. Good visualization for accessing the peripheral compartment generally is achieved by making the interportal capsulotomy 4 cm to 6 cm longer than the horizontal limb of the T-capsulotomy (Figures 2A, 2B). Capsular closure usually begins with the medial portion of the interportal capsulotomy. With the arthroscope in the AL portal, the 8.25-mm × 90-mm cannula is placed in the midanterior portal (MAP), and an 8.25-mm × 110-mm cannula is placed in the DALA portal.

Ligamentous laxity determines degree of capsular closure. The capsular leaflets can be closed end to end if there is little concern for laxity and instability. If there is more concern for capsular laxity, a larger bite of the capsular tissue can be taken to allow for a greater degree of plication. Further, the interportal capsule can be tightened by alternately advancing the location where sutures are passed through the capsule. Specifically, the sutures are passed such that larger bites of the distal capsule are taken, increasing the tightness of the capsule in external rotation.9

Rehabilitation

After surgery, hip extension and external rotation are limited to decrease stress on the capsular closure. The patient is placed into a hip orthosis with 0° to 90° of flexion and a night abduction pillow to limit hip external rotation. Crutch-assisted gait with 20 lb of foot-flat weight-bearing is maintained the first 3 weeks. Continuous passive motion and use of a stationary bicycle are recommended for the first 3 weeks, and then the patient slowly progresses to muscle strengthening, including core and proximal motor control. Closed-chain exercises are begun 6 weeks after surgery. Treadmill running may start at 12 weeks, with the goal of returning to sport at 4 to 6 months.

Discussion

Capsular closure during hip arthroscopy restores the normal anatomy of the IFL and therefore restores the biomechanical characteristics of the hip joint. Scientific studies have found that capsular repair or plication after hip arthroscopy restores normal hip translation, rotation, and strain. Clinical studies have also demonstrated a lower revision rate and more rapid return to athletic activity. Capsular closure, however, is technically challenging and increases operative time, but gross instability and microinstability can be avoided with meticulous closure/plication.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):49-54. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Hip capsule provides static stabilization for the hip joint.

- Capsular management must weigh visualization to address underlying osseous deformity but also repair/plication of the capsule to maintain biomechanical characteristics.

- T-capsulotomy provides optimal visualization with a small interportal incision with a vertical incision along the femoral neck.

- Extensile interportal capsulotomy is the most widely used capsulotomy and size may vary depending on capsular and patient characteristics.

- Orthopedic surgeons should be equipped to employ either technique depending on the patients individual hip pathomorphology.

Hip arthroscopy has emerged as a common surgical treatment for a number of hip pathologies. Surgical treatment strategies, including management of the hip capsule, have evolved. Whereas earlier hip arthroscopies often involved capsulectomy or capsulotomy without repair, more recently capsular closure has been considered an important step in restoring the anatomy of the hip joint and preventing microinstability or gross macroinstability.

The anatomy of the hip joint includes both static and dynamic stabilizers designed to maintain a functioning articulation. The osseous articulation of the femoral head and acetabulum is the first static stabilizer, with variations in offset, version, and inclination of the acetabulum and the proximal femur. The joint capsule consists of 3 ligaments—iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral—that converge to form the zona orbicularis. Other soft-tissue structures, such as the articular cartilage, the labrum, the transverse acetabular ligament, the pulvinar, and the ligamentum teres, also provide static constraint.1 The surrounding musculature provides the hip joint with dynamic stability, which contributes to overall maintenance of proper joint kinematics.

Management of the hip capsule has evolved as our understanding of hip pathology and biomechanics has matured. Initial articles on using hip arthroscopy to treat labral tears described improvement in clinical outcomes,2 but the cases involved limited focal capsulotomy. Not until the idea of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) was introduced were extensive capsulotomies and capsulectomies performed to address the underlying osseous deformities and emulate open techniques. Soon after our ability to access osseous pathomorphology improved with enhanced visualization and comprehensive resection, cases of hip instability after hip arthroscopy surfaced.3-5 Although frank dislocation after hip arthroscopy is rare and largely underreported, it is a catastrophic complication. In addition, focal capsular defects were also described in cases of failed hip arthroscopy and thought to lead to microinstability of the hip.6 Iatrogenic microinstability is thought to be more common, but it is also underrecognized as a cause of failure of hip arthroscopy.7Microinstability is a pathologic condition that can affect hip function. In cases of recurrent pain and unimproved functional status after surgery, microinstability should be considered. In an imaging study of capsule integrity, McCormick and colleagues6 found that 78% of patients who underwent revision arthroscopic surgery after hip arthroscopic surgery for FAI showed evidence of capsular and iliofemoral defects on magnetic resonance angiography. Frank and colleagues8 reported that, though all patients showed preoperative-to-postoperative improvement on outcome measures, those who underwent complete repair of their T-capsulotomy (vs repair of only its longitudinal portion) had superior outcomes, particularly increased sport-specific activity.

For patients undergoing hip arthroscopy, several predisposing factors can increase the risk of postoperative instability. Patient-related hip instability factors include generalized ligamentous laxity, supraphysiologic athletics (eg, dance), and borderline or true hip dysplasia. Surgeon-related factors include overaggressive acetabular rim resection, excessive labral débridement, and lack of capsular repair.5,9 Although there are multiple techniques for accessing the hip joint and addressing capsular closure at the end of surgery,9-14 we think capsular closure is an important aspect of the case.

Surgical Technique

For a demonstration of this technique, click here to see the video that accompanies this article. The patient is moved to a traction table and placed in the supine position. Induction of general anesthesia with muscle relaxation allows for atraumatic axial traction. The anesthetized patient is assessed for passive motion and ligamentous laxity. Well-padded boots are applied, and a well-padded perineal post is used for positioning. Gentle traction is applied to the contralateral limb, and axial traction is applied through the surgical limb with the hip abducted and minimally flexed. The leg is then adducted and neutrally extended, inducing a transverse vector cantilever moment to the proximal femur. The foot is internally rotated to optimize femoral neck length on an anteroposterior radiograph. The circulating nursing staff notes the onset of hip distraction in order to ensure safe traction duration.

Bony landmarks are marked with a sterile marking pen. Under fluoroscopic guidance, an anterolateral (AL) portal is established 1 cm proximal and 1 cm anterior to the AL tip of the greater trochanter. Standard cannulation allows for intra-articular visualization with a 70° arthroscope. A needle is used to localize placement of a modified anterior portal. After cannulation, the arthroscope is placed in the modified anterior portal to confirm safe entry of the portal without labral violation. An arthroscopic scalpel (Samurai Blade; Stryker Sports Medicine) is used to make a transverse interportal capsulotomy 8 mm to 10 mm from the labrum and extending from 12 to 2 o’clock; length is 2 cm to 4 cm, depending on the extent of the intra-articular injury (Figure 1A).

The acetabular rim is trimmed with a 5.0-mm arthroscopic burr. Distal AL accessory (DALA) portal placement (4-6 cm distal to and in line with the AL portal) allows for suture anchor–based labral refixation. Generally, 2 to 4 anchors (1.4-mm NanoTack Anatomic Labrum Restoration System; Stryker Sports Medicine) are placed as near the articular cartilage as possible without penetration (Figure 1B). On completion of labral refixation, traction is released, and the hip is flexed to 20° to 30°.

T-Capsulotomy

Pericapsular fatty tissue is débrided with an arthroscopic shaver to visualize the interval between the iliocapsularis and gluteus minimus muscles. An arthroscopic scalpel is used, through a 5.0-mm cannula in the DALA portal, to extend the capsulotomy longitudinally and perpendicular to the interportal capsulotomy (Figure 1C). The T-capsulotomy is performed along the length of the femoral neck distally to the capsular reflection at the intertrochanteric line. The arthroscopic burr is used to perform a femoral osteochondroplasty between the lateral synovial folds (12 o’clock) and the medial synovial folds (6 o’clock). Dynamic examination and fluoroscopic imaging confirm that the entire cam deformity has been excised and that there is no evidence of impingement.

Although various suture-shuttling or tissue-penetrating/retrieving devices may be used, we recommend whichever device is appropriate for closing the capsule in its entirety. With the arthroscope in the modified anterior portal, an 8.25-mm × 90-mm cannula is placed in the AL portal, and an 8.25-mm × 110-mm cannula in the DALA portal. These portals will facilitate suture passage.

The vertical limb of the T-capsulotomy is closed with 2 to 4 side-to-side sutures, and the interportal capsulotomy limb with 2 or 3 sutures. Capsular closure begins with the distal portion of the longitudinal limb at the base of the iliofemoral ligament (IFL). A crescent tissue penetrating device (Slingshot; Stryker Sports Medicine) is loaded with high-strength No. 2 suture (Zipline; Stryker Sports Medicine) and placed through the AL portal to sharply pierce the lateral leaflet of the IFL (Figure 1D). The No. 2 suture is shuttled into the intra-articular side of the capsule (Figure 1E). Through the DALA portal, the penetrating device is used to pierce the medial leaflet to retrieve the free suture (Figure 1F). Next, the looped suture retriever is used to pull the suture from the AL portal to the DALA portal so the suture can be tied. We prefer to tie each suture individually after it is passed, but all of the sutures can be passed first, and then tied. As successive suture placement and knot tying inherently tighten the capsule, successive visualization requires more precision. Each subsequent suture is similarly passed, about 1 cm proximal to the previous stitch.

After closure of the vertical limb of the T-capsulotomy, we prefer to close the interportal capsulotomy with the InJector II Capsule Restoration System (Stryker Sports Medicine), a device that allows for closure through a single cannula lateral to medial. This device is passed through the AL cannula in order to bring the suture end through the proximal IFL attached to the acetabulum (Figure 1G). The device is removed from the cannula, and the other suture end is placed in the device and passed through the distal IFL (Figure 1H). The stitch is then tensioned and tied. Likewise, closure of the medial IFL involves passing the InJector through the DALA cannula and bringing the first suture end through the proximal IFL attached to the acetabulum. The Injector is removed from the cannula, and the other suture end is placed in the device and passed through the distal IFL. The stitch is then tensioned and tied with the hip in neutral extension. Generally, 2 or 3 stitches are used to close the interportal capsulotomy. Complete capsular closure is confirmed by the inability to visualize the underlying femoral head/neck and by probing the anterior capsule to ensure proper tension (Figure 1I).

Extensile Interportal Capsulotomy

An alternative to T-capsulotomy is interportal capsulotomy. Just as with T-capsulotomy closure, multiple different suture passing devices can be used. Good visualization for accessing the peripheral compartment generally is achieved by making the interportal capsulotomy 4 cm to 6 cm longer than the horizontal limb of the T-capsulotomy (Figures 2A, 2B). Capsular closure usually begins with the medial portion of the interportal capsulotomy. With the arthroscope in the AL portal, the 8.25-mm × 90-mm cannula is placed in the midanterior portal (MAP), and an 8.25-mm × 110-mm cannula is placed in the DALA portal.

Ligamentous laxity determines degree of capsular closure. The capsular leaflets can be closed end to end if there is little concern for laxity and instability. If there is more concern for capsular laxity, a larger bite of the capsular tissue can be taken to allow for a greater degree of plication. Further, the interportal capsule can be tightened by alternately advancing the location where sutures are passed through the capsule. Specifically, the sutures are passed such that larger bites of the distal capsule are taken, increasing the tightness of the capsule in external rotation.9

Rehabilitation

After surgery, hip extension and external rotation are limited to decrease stress on the capsular closure. The patient is placed into a hip orthosis with 0° to 90° of flexion and a night abduction pillow to limit hip external rotation. Crutch-assisted gait with 20 lb of foot-flat weight-bearing is maintained the first 3 weeks. Continuous passive motion and use of a stationary bicycle are recommended for the first 3 weeks, and then the patient slowly progresses to muscle strengthening, including core and proximal motor control. Closed-chain exercises are begun 6 weeks after surgery. Treadmill running may start at 12 weeks, with the goal of returning to sport at 4 to 6 months.

Discussion

Capsular closure during hip arthroscopy restores the normal anatomy of the IFL and therefore restores the biomechanical characteristics of the hip joint. Scientific studies have found that capsular repair or plication after hip arthroscopy restores normal hip translation, rotation, and strain. Clinical studies have also demonstrated a lower revision rate and more rapid return to athletic activity. Capsular closure, however, is technically challenging and increases operative time, but gross instability and microinstability can be avoided with meticulous closure/plication.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):49-54. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Boykin RE, Anz AW, Bushnell BD, Kocher MS, Stubbs AJ, Philippon MJ. Hip instability. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(6):340-349.

2. Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy for labral pathology: prospective analysis with 10-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):365-368.

3. Benali Y, Katthagen BD. Hip subluxation as a complication of arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):405-407.

4. Matsuda DK. Acute iatrogenic dislocation following hip impingement arthroscopic surgery. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):400-404.

5. Ranawat AS, McClincy M, Sekiya JK. Anterior dislocation of the hip after arthroscopy in a patient with capsular laxity of the hip. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):192-197.

6. McCormick F, Slikker W 3rd, Harris JD, et al. Evidence of capsular defect following hip arthroscopy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):902-905.

7. Wylie JD, Beckmann JT, Maak TG, Aoki SK. Arthroscopic capsular repair for symptomatic hip instability after previous hip arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(1):39-45.

8. Frank RM, Lee S, Bush-Joseph CA, Kelly BT, Salata MJ, Nho SJ. Improved outcomes after hip arthroscopic surgery in patients undergoing T-capsulotomy with complete repair versus partial repair for femoroacetabular impingement: a comparative matched-pair analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(11):2634-2642.

9. Domb BG, Philippon MJ, Giordano BD. Arthroscopic capsulotomy, capsular repair, and capsular plication of the hip: relation to atraumatic instability. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(1):162-173.

10. Asopa V, Singh PJ. The intracapsular atraumatic arthroscopic technique for closure of the hip capsule. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(2):e245-e247.

11. Camp CL, Reardon PJ, Levy BA, Krych AJ. A simple technique for capsular repair after hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(6):e737-e740.

12. Chow RM, Engasser WM, Krych AJ, Levy BA. Arthroscopic capsular repair in the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(1):e27-e30.

13. Harris JD, Slikker W 3rd, Gupta AK, McCormick FM, Nho SJ. Routine complete capsular closure during hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(2):e89-e94.

14. Kuhns BD, Weber AE, Levy DM, et al. Capsular management in hip arthroscopy: an anatomic, biomechanical, and technical review. Front Surg. 2016;3:13.

1. Boykin RE, Anz AW, Bushnell BD, Kocher MS, Stubbs AJ, Philippon MJ. Hip instability. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(6):340-349.

2. Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy for labral pathology: prospective analysis with 10-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):365-368.

3. Benali Y, Katthagen BD. Hip subluxation as a complication of arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):405-407.

4. Matsuda DK. Acute iatrogenic dislocation following hip impingement arthroscopic surgery. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):400-404.

5. Ranawat AS, McClincy M, Sekiya JK. Anterior dislocation of the hip after arthroscopy in a patient with capsular laxity of the hip. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):192-197.

6. McCormick F, Slikker W 3rd, Harris JD, et al. Evidence of capsular defect following hip arthroscopy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):902-905.

7. Wylie JD, Beckmann JT, Maak TG, Aoki SK. Arthroscopic capsular repair for symptomatic hip instability after previous hip arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(1):39-45.

8. Frank RM, Lee S, Bush-Joseph CA, Kelly BT, Salata MJ, Nho SJ. Improved outcomes after hip arthroscopic surgery in patients undergoing T-capsulotomy with complete repair versus partial repair for femoroacetabular impingement: a comparative matched-pair analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(11):2634-2642.

9. Domb BG, Philippon MJ, Giordano BD. Arthroscopic capsulotomy, capsular repair, and capsular plication of the hip: relation to atraumatic instability. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(1):162-173.

10. Asopa V, Singh PJ. The intracapsular atraumatic arthroscopic technique for closure of the hip capsule. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(2):e245-e247.

11. Camp CL, Reardon PJ, Levy BA, Krych AJ. A simple technique for capsular repair after hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(6):e737-e740.

12. Chow RM, Engasser WM, Krych AJ, Levy BA. Arthroscopic capsular repair in the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(1):e27-e30.

13. Harris JD, Slikker W 3rd, Gupta AK, McCormick FM, Nho SJ. Routine complete capsular closure during hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(2):e89-e94.

14. Kuhns BD, Weber AE, Levy DM, et al. Capsular management in hip arthroscopy: an anatomic, biomechanical, and technical review. Front Surg. 2016;3:13.