User login

CASE Self Signing

Mrs. H, a 47-year-old, deaf, African American woman, is brought into the emergency room because she is becoming increasingly withdrawn and is signing to herself. She was hospitalized more than 10 years ago after developing psychotic symptoms and received a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, not otherwise specified. She was treated with olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, but she has not seen a psychiatrist or taken any psychotropics in 8 years. Upon admission to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Mrs. H reports, through an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, that she has had “problems with her parents” and with “being fair” and that she is 18 months pregnant. Urine pregnancy test is negative. Mrs. H also reports that her mother is pregnant. She indicates that it is difficult for her to describe what she is trying to say and that it is difficult to be deaf.

She endorses “very strong” racing thoughts, which she first states have been present for 15 years, then reports it has been 20 months. She endorses high-energy levels, feeling like there is “work to do,” and poor sleep. However, when asked, she indicates that she sleeps for 15 hours a day.

Which is critical when conducting a psychiatric assessment for a deaf patient?

a) rely only on the ASL interpreter

b) inquire about the patient’s communication preferences

c) use written language to communicate instead of speech

d) use a family member as interpreter

The authors’ observations

Mental health assessment of a deaf a patient involves a unique set of challenges and requires a specialized skill set for mental health practitioners—a skill set that is not routinely covered in psychiatric training programs.

a We use the term “deaf” to describe patients who have severe hearing loss. Other terms, such as “hearing impaired,” might be considered pejorative in the Deaf community. The term “Deaf” (capitalized) refers to Deaf culture and community, which deaf patients may or may not identify with.

Deafness history

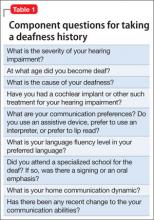

It is important to assess the cause of deafness,1,2 if known, and its age of onset (Table 1). A person is considered to be prelingually deaf if hearing loss was diagnosed before age 3.2 Clinicians should establish the patient’s communication preferences (use of assistive devices or interpreters or preference for lip reading), home communication dynamic,2 and language fluency level.1-3 Ask the patient if she attended a specialized school for the deaf and, if so, if there was an emphasis on oral communication or signing.2

HISTORY Conflicting reports

Mrs. H reports that she has been deaf since age 9, and that she learned sign language in India, where she became the “star king.” Mrs. H states that she then moved to the United States where she went to a school for the deaf. When asked if her family is able to communicate with her in sign language, she nods and indicates that they speak to her in “African and Indian.”

Mrs. H’s husband, who is hearing, says that Mrs. H is congenitally deaf, and was raised in the Midwestern United States where she attended a specialized school for the deaf. Mr. H and his 2 adult sons are hearing but communicate with Mrs. H in basic ASL. He states that Mrs. H sometimes uses signs that he and his sons cannot interpret. In addition to increased self-preoccupation and self-signing, Mrs. H has become more impulsive.

What are limitations of the mental status examination when evaluating a deaf patient?

a) facial expressions have a specific linguistic function in ASL

b) there is no differentiation in the mental status exam of deaf patients from that of hearing patients

c) the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a validated tool to assess cognition in deaf patients

d) the clinician should not rely on the interpreter to assist with the mental status examination

The authors’ observation

Performing a mental status examination of a deaf patient without recognizing some of the challenges inherent to this task can lead to misleading findings. For example, signing and gesturing can give the clinician an impression of psychomotor agitation.2 What appears to be socially withdrawn behavior might be a reaction to the patient’s inability to communicate with others.2,3 Social skills may be affected by language deprivation, if present.3 In ASL, facial expressions have specific linguistic functions in addition to representing emotions,2 and can affect the meaning of the sign used. An exaggerated or intense facial expression with the sign “quiet,” for example, usually means “very quiet.”4 In assessing cognition, the MMSE is not available in ASL and has not been validated in deaf patients.5 Also, deaf people have reduced access to information, and a lack of knowledge does not necessarily correlate with low IQ.2

The interpreter’s role

An ASL interpreter can aid in assessing a deaf patient’s communication skills. The interpreter can help with a thorough language evaluation1,6 and provide information about socio-cultural norms in the Deaf community.7 Using an ASL interpreter with special training in mental health1,3,6,7 is important to accurately diagnose thought disorders in deaf patients.1

EVALUATION Mental status exam

Mrs. H is poorly groomed and is wearing a pink housecoat, with her hair in disarray. She seems to be distracted by something next to the interpreter, because her eyes keep roving in this direction. She has moderate psychomotor agitation, based on the rapidity of her signing and gesturing. Mrs. H makes indecipherable vocalizations while signing, often loud and with an urgent quality. Her affect is elevated and expansive. She is not oriented to place or time and when asked where she is, signs, “many times, every day, 6-9-9, 2-5, more trouble…”

The ASL interpreter notes that Mrs. H signs so quickly that only about one-half of her signs are interpretable. Mrs. H’s grammar is not always correct and that her syntax is, at times, inappropriate. Mrs. H’s letters are difficult to interpret because she often starts and concludes a word with a clear sign, but the intervening letters are rapid and uninterpretable. She also uses several non-alphabet signs that cannot be interpreted (approximately 10% to 15% of signs) and repeats signs without clear context, such as “nothing off.” Mrs. H can pause to clarify for the interpreter at the beginning of the interview but is not able to do so by the end of the interview.

How does assessment of psychosis differ when evaluating deaf patients?

a) language dysfluency must be carefully differentiated from a thought disorder

b) signing to oneself does not necessarily indicate a response to internal stimuli

c) norms in Deaf culture might be misconstrued as delusions

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

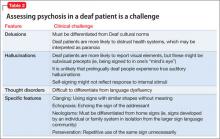

The prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients is unknown.8 Although older studies have reported an increased prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients, these studies suffer from methodological problems.1 Other studies are at odds with each other, variably reporting a greater,9 equivalent,10 and lesser incidence of psychotic disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients.11 Deaf patients with psychotic disorders experience delusions, hallucinations, and thought disorders,1,3 and assessing for these symptoms in deaf patients can present a diagnostic challenge (Table 2).

Delusions are thought to present similarly in deaf patients with psychotic disorders compared with hearing patients.1,3 Paranoia may be increased in patients who are postlingually deaf, but has not been associated with prelingual deafness. Deficits in theory of mind related to hearing impairment have been thought to contribute to delusions in deaf patients.1,12

Many deaf patients distrust health care systems and providers,2,3,13 which may be misinterpreted as paranoia. Poor communication between deaf patients and clinicians and poor health literacy among deaf patients contribute to feelings of mistrust. Deaf patients often report experiencing prejudice within the health care system, and think that providers lack sufficient knowledge of deafness.13 Care must be taken to ensure that Deaf cultural norms are not misinterpreted as delusions.

Hallucinations. How deaf patients experience hallucinations, especially in prelingual deafness, likely is different from hallucinatory experiences of hearing patients.1,14 Deaf people with psychosis have described ”ideas coming into one’s head” and an almost “telepathic” process of “knowing.”14 Deaf patients with schizophrenia are more likely to report visual elements to their hallucinations; however, these may be subvisual precepts rather than true visual hallucinations.1,15 For example, hallucination might include the perception of being signed to.1

Deaf patients’ experience of auditory hallucinations is thought to be closely related to past auditory experiences. It is unlikely that prelingually deaf patients experience true auditory hallucinations.1,14 An endorsement of hearing a “voice” in ASL does not necessarily translate to an audiological experience.15 If profoundly prelingually deaf patients endorse hearing voices, generally they cannot assign acoustic properties (pitch, tone, volume, accent, etc.).1,14,15 It may not be necessary to fully comprehend the precise modality of how hallucinations are experienced by deaf patients to provide therapy.14

Self-signing, or signing to oneself, does not necessarily indicate that a deaf person is responding to a hallucinatory experience. Non-verbal patients may gesture to themselves without clear evidence of psychosis. When considering whether a patient is experiencing hallucinations, it is important to look for other evidence of psychosis.3

Possible approaches to evaluating hallucinations in deaf patients include asking,, “is someone signing in your head?” or “Is someone who is not in the room trying to communicate with you?”

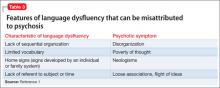

Thought disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients are difficult to diagnose, in part because of a high rate of language dysfluency in deaf patients; in samples of psychiatric inpatients, 75% are not fluent in ASL, 66% are not fluent in any language).1,3,11 Commonly, language dysfluency is related to language deprivation because of late or inadequate exposure to ASL, although it may be related to neurologic damage or aphasia.1,3,6,16 Deaf patients can have additional disabilities, including learning disabilities, that might contribute to language dysfluency.2 Language dysfluency can be misattributed to a psychotic process1-3,7 (Table 3).1

Language dysfluency and thought disorders can be difficult to differentiate and may be comorbid. Loose associations and flight of ideas can be hard to assess in patients with language dysfluency. In general, increasing looseness of association between concepts corresponds to an increasing likelihood that a patient has true loose associations rather than language dysfluency alone.3 Deaf patients with schizophrenia can be identified by the presence of associated symptoms of psychosis, especially if delusions are present.1,3

EVALUATION Psychotic symptoms

Mrs. H’s thought process appears disorganized and illogical, with flight of ideas. She might have an underlying language dysfluency. It is likely that Mrs. H is using neologisms to communicate because of her family’s lack of familiarity with some of her signs. She also demonstrates perseveration, with use of certain signs repeatedly without clear context (ie, “nothing off”).

Her thought content includes racial themes—she mentions Russia, Germany, and Vietnam without clear context—and delusions of being the “star king” and of being pregnant. She endorses paranoid feelings that people on the inpatient unit are trying to hurt her, although it isn’t clear whether this represents a true paranoid delusion because of the hectic climate of the unit, and she did not show unnecessarily defensive or guarded behaviors.

She is seen signing to herself in the dayroom and endorses feeling as though someone who is not in the room—described as an Indian teacher (and sometimes as a boss or principal) known as “Mr. Smith” or “Mr. Donald”—is trying to communicate with her. She describes this person as being male and female. She mentions that sometimes she sees an Indian man and another man fighting. It is likely that Mrs. H is experiencing hallucinations from decompensated psychosis, because of the constellation and trajectory of her symptoms. Her nonverbal behavior—her eyes rove around the room during interviews—also supports this conclusion.

Because of evidence of mood and psychotic symptoms, and with a collateral history that suggests significant baseline disorganization, Mrs. H receives a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. She is restarted on olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d.

Mrs. H’s psychomotor acceleration and affective elevation gradually improve with pharmacotherapy. After a 2-week hospitalization, despite ongoing disorganization and self-signing, Mrs. H’s husband says that he feels she is improved enough to return home, with plans to continue to take her medications and to reestablish outpatient follow-up.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric assessment of deaf patients presents distinctive challenges related to cultural and language barriers—making it important to engage an ASL interpreter with training in mental health during assessment of a deaf patient. Clinicians must become familiar with these challenges to provide effective care for mentally ill deaf patients.

Related Resources

• Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Communicating with deaf patients: 10 tips to deliver appropriate care. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):36-37.

• Deaf Wellness Center. University of Rochester School of Medicine. www.urmc.rochester.edu/deaf-wellness-center.

• Gallaudet University Mental Health Center. www.gallaudet.edu/

mental_health_center.html.

Drug Brand Names

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Identifying and assessing psychosis in deaf psychiatric patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):198-202.

2. Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Pollard R. Mental health of deaf people. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1037-1044.

3. Glickman N. Do you hear voices? Problems in assessment of mental status in deaf persons with severe language deprivation. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12(2):127-147.

4. Vicars W. ASL University. Facial expressions. http://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/pages-layout/facialexpressions.htm. Accessed April 2, 2013.

5. Dean PM, Feldman DM, Morere D, et al. Clinical evaluation of the mini-mental state exam with culturally deaf senior citizens. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24(8):753-760.

6. Crump C, Glickman N. Mental health interpreting with language dysfluent deaf clients. Journal of Interpretation. 2011;21(1):21-36.

7. Leigh IW, Pollard RQ Jr. Mental health and deaf adults. In: Marschark M, Spencer PE, eds. Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education. Vol 1. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2011:214-226.

8. Øhre B, von Tezchner S, Falkum E. Deaf adults and mental health: A review of recent research on the prevalence and distribution of psychiatric symptoms and disorders in the prelingually deaf adult population. International Journal on Mental Health and Deafness. 2011;1(1):3-22.

9. Appleford J. Clinical activity within a specialist mental health service for deaf people: comparison with a general psychiatric service. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27(10): 375-377.

10. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Inpatient psychiatric treatment of deaf adults: demographic and diagnostic comparisons with hearing inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):196-199.

11. Black PA, Glickman NS. Demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, and other characteristics of North American deaf and hard-of-hearing inpatients. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2006; 11(3):303-321.

12. Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall R, et al. Hearing impairment and psychosis revisited. Schizophr Res. 2005; 76(1):99-103.

13. Steinberg AG, Barnett S, Meador HE, et al. Health care system accessibility. Experiences and perceptions of deaf people. J Gen Inter Med. 2006;21(3):260-266.

14. Paijmans R, Cromwell J, Austen S. Do profoundly prelingually deaf patients with psychosis really hear voices? Am Ann Deaf. 2006;151(1):42-48.

15. Atkinson JR. The perceptual characteristics of voice-hallucinations in deaf people: insights into the nature of subvocal thought and sensory feedback loops. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):701-708.

16. Trumbetta SL, Bonvillian JD, Siedlecki T, et al. Language-related symptoms in persons with schizophrenia and how deaf persons may manifest these symptoms. Sign Language Studies. 2001;1(3):228-253.

CASE Self Signing

Mrs. H, a 47-year-old, deaf, African American woman, is brought into the emergency room because she is becoming increasingly withdrawn and is signing to herself. She was hospitalized more than 10 years ago after developing psychotic symptoms and received a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, not otherwise specified. She was treated with olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, but she has not seen a psychiatrist or taken any psychotropics in 8 years. Upon admission to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Mrs. H reports, through an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, that she has had “problems with her parents” and with “being fair” and that she is 18 months pregnant. Urine pregnancy test is negative. Mrs. H also reports that her mother is pregnant. She indicates that it is difficult for her to describe what she is trying to say and that it is difficult to be deaf.

She endorses “very strong” racing thoughts, which she first states have been present for 15 years, then reports it has been 20 months. She endorses high-energy levels, feeling like there is “work to do,” and poor sleep. However, when asked, she indicates that she sleeps for 15 hours a day.

Which is critical when conducting a psychiatric assessment for a deaf patient?

a) rely only on the ASL interpreter

b) inquire about the patient’s communication preferences

c) use written language to communicate instead of speech

d) use a family member as interpreter

The authors’ observations

Mental health assessment of a deaf a patient involves a unique set of challenges and requires a specialized skill set for mental health practitioners—a skill set that is not routinely covered in psychiatric training programs.

a We use the term “deaf” to describe patients who have severe hearing loss. Other terms, such as “hearing impaired,” might be considered pejorative in the Deaf community. The term “Deaf” (capitalized) refers to Deaf culture and community, which deaf patients may or may not identify with.

Deafness history

It is important to assess the cause of deafness,1,2 if known, and its age of onset (Table 1). A person is considered to be prelingually deaf if hearing loss was diagnosed before age 3.2 Clinicians should establish the patient’s communication preferences (use of assistive devices or interpreters or preference for lip reading), home communication dynamic,2 and language fluency level.1-3 Ask the patient if she attended a specialized school for the deaf and, if so, if there was an emphasis on oral communication or signing.2

HISTORY Conflicting reports

Mrs. H reports that she has been deaf since age 9, and that she learned sign language in India, where she became the “star king.” Mrs. H states that she then moved to the United States where she went to a school for the deaf. When asked if her family is able to communicate with her in sign language, she nods and indicates that they speak to her in “African and Indian.”

Mrs. H’s husband, who is hearing, says that Mrs. H is congenitally deaf, and was raised in the Midwestern United States where she attended a specialized school for the deaf. Mr. H and his 2 adult sons are hearing but communicate with Mrs. H in basic ASL. He states that Mrs. H sometimes uses signs that he and his sons cannot interpret. In addition to increased self-preoccupation and self-signing, Mrs. H has become more impulsive.

What are limitations of the mental status examination when evaluating a deaf patient?

a) facial expressions have a specific linguistic function in ASL

b) there is no differentiation in the mental status exam of deaf patients from that of hearing patients

c) the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a validated tool to assess cognition in deaf patients

d) the clinician should not rely on the interpreter to assist with the mental status examination

The authors’ observation

Performing a mental status examination of a deaf patient without recognizing some of the challenges inherent to this task can lead to misleading findings. For example, signing and gesturing can give the clinician an impression of psychomotor agitation.2 What appears to be socially withdrawn behavior might be a reaction to the patient’s inability to communicate with others.2,3 Social skills may be affected by language deprivation, if present.3 In ASL, facial expressions have specific linguistic functions in addition to representing emotions,2 and can affect the meaning of the sign used. An exaggerated or intense facial expression with the sign “quiet,” for example, usually means “very quiet.”4 In assessing cognition, the MMSE is not available in ASL and has not been validated in deaf patients.5 Also, deaf people have reduced access to information, and a lack of knowledge does not necessarily correlate with low IQ.2

The interpreter’s role

An ASL interpreter can aid in assessing a deaf patient’s communication skills. The interpreter can help with a thorough language evaluation1,6 and provide information about socio-cultural norms in the Deaf community.7 Using an ASL interpreter with special training in mental health1,3,6,7 is important to accurately diagnose thought disorders in deaf patients.1

EVALUATION Mental status exam

Mrs. H is poorly groomed and is wearing a pink housecoat, with her hair in disarray. She seems to be distracted by something next to the interpreter, because her eyes keep roving in this direction. She has moderate psychomotor agitation, based on the rapidity of her signing and gesturing. Mrs. H makes indecipherable vocalizations while signing, often loud and with an urgent quality. Her affect is elevated and expansive. She is not oriented to place or time and when asked where she is, signs, “many times, every day, 6-9-9, 2-5, more trouble…”

The ASL interpreter notes that Mrs. H signs so quickly that only about one-half of her signs are interpretable. Mrs. H’s grammar is not always correct and that her syntax is, at times, inappropriate. Mrs. H’s letters are difficult to interpret because she often starts and concludes a word with a clear sign, but the intervening letters are rapid and uninterpretable. She also uses several non-alphabet signs that cannot be interpreted (approximately 10% to 15% of signs) and repeats signs without clear context, such as “nothing off.” Mrs. H can pause to clarify for the interpreter at the beginning of the interview but is not able to do so by the end of the interview.

How does assessment of psychosis differ when evaluating deaf patients?

a) language dysfluency must be carefully differentiated from a thought disorder

b) signing to oneself does not necessarily indicate a response to internal stimuli

c) norms in Deaf culture might be misconstrued as delusions

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

The prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients is unknown.8 Although older studies have reported an increased prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients, these studies suffer from methodological problems.1 Other studies are at odds with each other, variably reporting a greater,9 equivalent,10 and lesser incidence of psychotic disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients.11 Deaf patients with psychotic disorders experience delusions, hallucinations, and thought disorders,1,3 and assessing for these symptoms in deaf patients can present a diagnostic challenge (Table 2).

Delusions are thought to present similarly in deaf patients with psychotic disorders compared with hearing patients.1,3 Paranoia may be increased in patients who are postlingually deaf, but has not been associated with prelingual deafness. Deficits in theory of mind related to hearing impairment have been thought to contribute to delusions in deaf patients.1,12

Many deaf patients distrust health care systems and providers,2,3,13 which may be misinterpreted as paranoia. Poor communication between deaf patients and clinicians and poor health literacy among deaf patients contribute to feelings of mistrust. Deaf patients often report experiencing prejudice within the health care system, and think that providers lack sufficient knowledge of deafness.13 Care must be taken to ensure that Deaf cultural norms are not misinterpreted as delusions.

Hallucinations. How deaf patients experience hallucinations, especially in prelingual deafness, likely is different from hallucinatory experiences of hearing patients.1,14 Deaf people with psychosis have described ”ideas coming into one’s head” and an almost “telepathic” process of “knowing.”14 Deaf patients with schizophrenia are more likely to report visual elements to their hallucinations; however, these may be subvisual precepts rather than true visual hallucinations.1,15 For example, hallucination might include the perception of being signed to.1

Deaf patients’ experience of auditory hallucinations is thought to be closely related to past auditory experiences. It is unlikely that prelingually deaf patients experience true auditory hallucinations.1,14 An endorsement of hearing a “voice” in ASL does not necessarily translate to an audiological experience.15 If profoundly prelingually deaf patients endorse hearing voices, generally they cannot assign acoustic properties (pitch, tone, volume, accent, etc.).1,14,15 It may not be necessary to fully comprehend the precise modality of how hallucinations are experienced by deaf patients to provide therapy.14

Self-signing, or signing to oneself, does not necessarily indicate that a deaf person is responding to a hallucinatory experience. Non-verbal patients may gesture to themselves without clear evidence of psychosis. When considering whether a patient is experiencing hallucinations, it is important to look for other evidence of psychosis.3

Possible approaches to evaluating hallucinations in deaf patients include asking,, “is someone signing in your head?” or “Is someone who is not in the room trying to communicate with you?”

Thought disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients are difficult to diagnose, in part because of a high rate of language dysfluency in deaf patients; in samples of psychiatric inpatients, 75% are not fluent in ASL, 66% are not fluent in any language).1,3,11 Commonly, language dysfluency is related to language deprivation because of late or inadequate exposure to ASL, although it may be related to neurologic damage or aphasia.1,3,6,16 Deaf patients can have additional disabilities, including learning disabilities, that might contribute to language dysfluency.2 Language dysfluency can be misattributed to a psychotic process1-3,7 (Table 3).1

Language dysfluency and thought disorders can be difficult to differentiate and may be comorbid. Loose associations and flight of ideas can be hard to assess in patients with language dysfluency. In general, increasing looseness of association between concepts corresponds to an increasing likelihood that a patient has true loose associations rather than language dysfluency alone.3 Deaf patients with schizophrenia can be identified by the presence of associated symptoms of psychosis, especially if delusions are present.1,3

EVALUATION Psychotic symptoms

Mrs. H’s thought process appears disorganized and illogical, with flight of ideas. She might have an underlying language dysfluency. It is likely that Mrs. H is using neologisms to communicate because of her family’s lack of familiarity with some of her signs. She also demonstrates perseveration, with use of certain signs repeatedly without clear context (ie, “nothing off”).

Her thought content includes racial themes—she mentions Russia, Germany, and Vietnam without clear context—and delusions of being the “star king” and of being pregnant. She endorses paranoid feelings that people on the inpatient unit are trying to hurt her, although it isn’t clear whether this represents a true paranoid delusion because of the hectic climate of the unit, and she did not show unnecessarily defensive or guarded behaviors.

She is seen signing to herself in the dayroom and endorses feeling as though someone who is not in the room—described as an Indian teacher (and sometimes as a boss or principal) known as “Mr. Smith” or “Mr. Donald”—is trying to communicate with her. She describes this person as being male and female. She mentions that sometimes she sees an Indian man and another man fighting. It is likely that Mrs. H is experiencing hallucinations from decompensated psychosis, because of the constellation and trajectory of her symptoms. Her nonverbal behavior—her eyes rove around the room during interviews—also supports this conclusion.

Because of evidence of mood and psychotic symptoms, and with a collateral history that suggests significant baseline disorganization, Mrs. H receives a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. She is restarted on olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d.

Mrs. H’s psychomotor acceleration and affective elevation gradually improve with pharmacotherapy. After a 2-week hospitalization, despite ongoing disorganization and self-signing, Mrs. H’s husband says that he feels she is improved enough to return home, with plans to continue to take her medications and to reestablish outpatient follow-up.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric assessment of deaf patients presents distinctive challenges related to cultural and language barriers—making it important to engage an ASL interpreter with training in mental health during assessment of a deaf patient. Clinicians must become familiar with these challenges to provide effective care for mentally ill deaf patients.

Related Resources

• Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Communicating with deaf patients: 10 tips to deliver appropriate care. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):36-37.

• Deaf Wellness Center. University of Rochester School of Medicine. www.urmc.rochester.edu/deaf-wellness-center.

• Gallaudet University Mental Health Center. www.gallaudet.edu/

mental_health_center.html.

Drug Brand Names

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Self Signing

Mrs. H, a 47-year-old, deaf, African American woman, is brought into the emergency room because she is becoming increasingly withdrawn and is signing to herself. She was hospitalized more than 10 years ago after developing psychotic symptoms and received a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, not otherwise specified. She was treated with olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, but she has not seen a psychiatrist or taken any psychotropics in 8 years. Upon admission to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Mrs. H reports, through an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, that she has had “problems with her parents” and with “being fair” and that she is 18 months pregnant. Urine pregnancy test is negative. Mrs. H also reports that her mother is pregnant. She indicates that it is difficult for her to describe what she is trying to say and that it is difficult to be deaf.

She endorses “very strong” racing thoughts, which she first states have been present for 15 years, then reports it has been 20 months. She endorses high-energy levels, feeling like there is “work to do,” and poor sleep. However, when asked, she indicates that she sleeps for 15 hours a day.

Which is critical when conducting a psychiatric assessment for a deaf patient?

a) rely only on the ASL interpreter

b) inquire about the patient’s communication preferences

c) use written language to communicate instead of speech

d) use a family member as interpreter

The authors’ observations

Mental health assessment of a deaf a patient involves a unique set of challenges and requires a specialized skill set for mental health practitioners—a skill set that is not routinely covered in psychiatric training programs.

a We use the term “deaf” to describe patients who have severe hearing loss. Other terms, such as “hearing impaired,” might be considered pejorative in the Deaf community. The term “Deaf” (capitalized) refers to Deaf culture and community, which deaf patients may or may not identify with.

Deafness history

It is important to assess the cause of deafness,1,2 if known, and its age of onset (Table 1). A person is considered to be prelingually deaf if hearing loss was diagnosed before age 3.2 Clinicians should establish the patient’s communication preferences (use of assistive devices or interpreters or preference for lip reading), home communication dynamic,2 and language fluency level.1-3 Ask the patient if she attended a specialized school for the deaf and, if so, if there was an emphasis on oral communication or signing.2

HISTORY Conflicting reports

Mrs. H reports that she has been deaf since age 9, and that she learned sign language in India, where she became the “star king.” Mrs. H states that she then moved to the United States where she went to a school for the deaf. When asked if her family is able to communicate with her in sign language, she nods and indicates that they speak to her in “African and Indian.”

Mrs. H’s husband, who is hearing, says that Mrs. H is congenitally deaf, and was raised in the Midwestern United States where she attended a specialized school for the deaf. Mr. H and his 2 adult sons are hearing but communicate with Mrs. H in basic ASL. He states that Mrs. H sometimes uses signs that he and his sons cannot interpret. In addition to increased self-preoccupation and self-signing, Mrs. H has become more impulsive.

What are limitations of the mental status examination when evaluating a deaf patient?

a) facial expressions have a specific linguistic function in ASL

b) there is no differentiation in the mental status exam of deaf patients from that of hearing patients

c) the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a validated tool to assess cognition in deaf patients

d) the clinician should not rely on the interpreter to assist with the mental status examination

The authors’ observation

Performing a mental status examination of a deaf patient without recognizing some of the challenges inherent to this task can lead to misleading findings. For example, signing and gesturing can give the clinician an impression of psychomotor agitation.2 What appears to be socially withdrawn behavior might be a reaction to the patient’s inability to communicate with others.2,3 Social skills may be affected by language deprivation, if present.3 In ASL, facial expressions have specific linguistic functions in addition to representing emotions,2 and can affect the meaning of the sign used. An exaggerated or intense facial expression with the sign “quiet,” for example, usually means “very quiet.”4 In assessing cognition, the MMSE is not available in ASL and has not been validated in deaf patients.5 Also, deaf people have reduced access to information, and a lack of knowledge does not necessarily correlate with low IQ.2

The interpreter’s role

An ASL interpreter can aid in assessing a deaf patient’s communication skills. The interpreter can help with a thorough language evaluation1,6 and provide information about socio-cultural norms in the Deaf community.7 Using an ASL interpreter with special training in mental health1,3,6,7 is important to accurately diagnose thought disorders in deaf patients.1

EVALUATION Mental status exam

Mrs. H is poorly groomed and is wearing a pink housecoat, with her hair in disarray. She seems to be distracted by something next to the interpreter, because her eyes keep roving in this direction. She has moderate psychomotor agitation, based on the rapidity of her signing and gesturing. Mrs. H makes indecipherable vocalizations while signing, often loud and with an urgent quality. Her affect is elevated and expansive. She is not oriented to place or time and when asked where she is, signs, “many times, every day, 6-9-9, 2-5, more trouble…”

The ASL interpreter notes that Mrs. H signs so quickly that only about one-half of her signs are interpretable. Mrs. H’s grammar is not always correct and that her syntax is, at times, inappropriate. Mrs. H’s letters are difficult to interpret because she often starts and concludes a word with a clear sign, but the intervening letters are rapid and uninterpretable. She also uses several non-alphabet signs that cannot be interpreted (approximately 10% to 15% of signs) and repeats signs without clear context, such as “nothing off.” Mrs. H can pause to clarify for the interpreter at the beginning of the interview but is not able to do so by the end of the interview.

How does assessment of psychosis differ when evaluating deaf patients?

a) language dysfluency must be carefully differentiated from a thought disorder

b) signing to oneself does not necessarily indicate a response to internal stimuli

c) norms in Deaf culture might be misconstrued as delusions

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

The prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients is unknown.8 Although older studies have reported an increased prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients, these studies suffer from methodological problems.1 Other studies are at odds with each other, variably reporting a greater,9 equivalent,10 and lesser incidence of psychotic disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients.11 Deaf patients with psychotic disorders experience delusions, hallucinations, and thought disorders,1,3 and assessing for these symptoms in deaf patients can present a diagnostic challenge (Table 2).

Delusions are thought to present similarly in deaf patients with psychotic disorders compared with hearing patients.1,3 Paranoia may be increased in patients who are postlingually deaf, but has not been associated with prelingual deafness. Deficits in theory of mind related to hearing impairment have been thought to contribute to delusions in deaf patients.1,12

Many deaf patients distrust health care systems and providers,2,3,13 which may be misinterpreted as paranoia. Poor communication between deaf patients and clinicians and poor health literacy among deaf patients contribute to feelings of mistrust. Deaf patients often report experiencing prejudice within the health care system, and think that providers lack sufficient knowledge of deafness.13 Care must be taken to ensure that Deaf cultural norms are not misinterpreted as delusions.

Hallucinations. How deaf patients experience hallucinations, especially in prelingual deafness, likely is different from hallucinatory experiences of hearing patients.1,14 Deaf people with psychosis have described ”ideas coming into one’s head” and an almost “telepathic” process of “knowing.”14 Deaf patients with schizophrenia are more likely to report visual elements to their hallucinations; however, these may be subvisual precepts rather than true visual hallucinations.1,15 For example, hallucination might include the perception of being signed to.1

Deaf patients’ experience of auditory hallucinations is thought to be closely related to past auditory experiences. It is unlikely that prelingually deaf patients experience true auditory hallucinations.1,14 An endorsement of hearing a “voice” in ASL does not necessarily translate to an audiological experience.15 If profoundly prelingually deaf patients endorse hearing voices, generally they cannot assign acoustic properties (pitch, tone, volume, accent, etc.).1,14,15 It may not be necessary to fully comprehend the precise modality of how hallucinations are experienced by deaf patients to provide therapy.14

Self-signing, or signing to oneself, does not necessarily indicate that a deaf person is responding to a hallucinatory experience. Non-verbal patients may gesture to themselves without clear evidence of psychosis. When considering whether a patient is experiencing hallucinations, it is important to look for other evidence of psychosis.3

Possible approaches to evaluating hallucinations in deaf patients include asking,, “is someone signing in your head?” or “Is someone who is not in the room trying to communicate with you?”

Thought disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients are difficult to diagnose, in part because of a high rate of language dysfluency in deaf patients; in samples of psychiatric inpatients, 75% are not fluent in ASL, 66% are not fluent in any language).1,3,11 Commonly, language dysfluency is related to language deprivation because of late or inadequate exposure to ASL, although it may be related to neurologic damage or aphasia.1,3,6,16 Deaf patients can have additional disabilities, including learning disabilities, that might contribute to language dysfluency.2 Language dysfluency can be misattributed to a psychotic process1-3,7 (Table 3).1

Language dysfluency and thought disorders can be difficult to differentiate and may be comorbid. Loose associations and flight of ideas can be hard to assess in patients with language dysfluency. In general, increasing looseness of association between concepts corresponds to an increasing likelihood that a patient has true loose associations rather than language dysfluency alone.3 Deaf patients with schizophrenia can be identified by the presence of associated symptoms of psychosis, especially if delusions are present.1,3

EVALUATION Psychotic symptoms

Mrs. H’s thought process appears disorganized and illogical, with flight of ideas. She might have an underlying language dysfluency. It is likely that Mrs. H is using neologisms to communicate because of her family’s lack of familiarity with some of her signs. She also demonstrates perseveration, with use of certain signs repeatedly without clear context (ie, “nothing off”).

Her thought content includes racial themes—she mentions Russia, Germany, and Vietnam without clear context—and delusions of being the “star king” and of being pregnant. She endorses paranoid feelings that people on the inpatient unit are trying to hurt her, although it isn’t clear whether this represents a true paranoid delusion because of the hectic climate of the unit, and she did not show unnecessarily defensive or guarded behaviors.

She is seen signing to herself in the dayroom and endorses feeling as though someone who is not in the room—described as an Indian teacher (and sometimes as a boss or principal) known as “Mr. Smith” or “Mr. Donald”—is trying to communicate with her. She describes this person as being male and female. She mentions that sometimes she sees an Indian man and another man fighting. It is likely that Mrs. H is experiencing hallucinations from decompensated psychosis, because of the constellation and trajectory of her symptoms. Her nonverbal behavior—her eyes rove around the room during interviews—also supports this conclusion.

Because of evidence of mood and psychotic symptoms, and with a collateral history that suggests significant baseline disorganization, Mrs. H receives a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. She is restarted on olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d.

Mrs. H’s psychomotor acceleration and affective elevation gradually improve with pharmacotherapy. After a 2-week hospitalization, despite ongoing disorganization and self-signing, Mrs. H’s husband says that he feels she is improved enough to return home, with plans to continue to take her medications and to reestablish outpatient follow-up.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric assessment of deaf patients presents distinctive challenges related to cultural and language barriers—making it important to engage an ASL interpreter with training in mental health during assessment of a deaf patient. Clinicians must become familiar with these challenges to provide effective care for mentally ill deaf patients.

Related Resources

• Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Communicating with deaf patients: 10 tips to deliver appropriate care. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):36-37.

• Deaf Wellness Center. University of Rochester School of Medicine. www.urmc.rochester.edu/deaf-wellness-center.

• Gallaudet University Mental Health Center. www.gallaudet.edu/

mental_health_center.html.

Drug Brand Names

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Identifying and assessing psychosis in deaf psychiatric patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):198-202.

2. Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Pollard R. Mental health of deaf people. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1037-1044.

3. Glickman N. Do you hear voices? Problems in assessment of mental status in deaf persons with severe language deprivation. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12(2):127-147.

4. Vicars W. ASL University. Facial expressions. http://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/pages-layout/facialexpressions.htm. Accessed April 2, 2013.

5. Dean PM, Feldman DM, Morere D, et al. Clinical evaluation of the mini-mental state exam with culturally deaf senior citizens. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24(8):753-760.

6. Crump C, Glickman N. Mental health interpreting with language dysfluent deaf clients. Journal of Interpretation. 2011;21(1):21-36.

7. Leigh IW, Pollard RQ Jr. Mental health and deaf adults. In: Marschark M, Spencer PE, eds. Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education. Vol 1. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2011:214-226.

8. Øhre B, von Tezchner S, Falkum E. Deaf adults and mental health: A review of recent research on the prevalence and distribution of psychiatric symptoms and disorders in the prelingually deaf adult population. International Journal on Mental Health and Deafness. 2011;1(1):3-22.

9. Appleford J. Clinical activity within a specialist mental health service for deaf people: comparison with a general psychiatric service. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27(10): 375-377.

10. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Inpatient psychiatric treatment of deaf adults: demographic and diagnostic comparisons with hearing inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):196-199.

11. Black PA, Glickman NS. Demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, and other characteristics of North American deaf and hard-of-hearing inpatients. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2006; 11(3):303-321.

12. Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall R, et al. Hearing impairment and psychosis revisited. Schizophr Res. 2005; 76(1):99-103.

13. Steinberg AG, Barnett S, Meador HE, et al. Health care system accessibility. Experiences and perceptions of deaf people. J Gen Inter Med. 2006;21(3):260-266.

14. Paijmans R, Cromwell J, Austen S. Do profoundly prelingually deaf patients with psychosis really hear voices? Am Ann Deaf. 2006;151(1):42-48.

15. Atkinson JR. The perceptual characteristics of voice-hallucinations in deaf people: insights into the nature of subvocal thought and sensory feedback loops. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):701-708.

16. Trumbetta SL, Bonvillian JD, Siedlecki T, et al. Language-related symptoms in persons with schizophrenia and how deaf persons may manifest these symptoms. Sign Language Studies. 2001;1(3):228-253.

1. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Identifying and assessing psychosis in deaf psychiatric patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):198-202.

2. Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Pollard R. Mental health of deaf people. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1037-1044.

3. Glickman N. Do you hear voices? Problems in assessment of mental status in deaf persons with severe language deprivation. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12(2):127-147.

4. Vicars W. ASL University. Facial expressions. http://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/pages-layout/facialexpressions.htm. Accessed April 2, 2013.

5. Dean PM, Feldman DM, Morere D, et al. Clinical evaluation of the mini-mental state exam with culturally deaf senior citizens. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24(8):753-760.

6. Crump C, Glickman N. Mental health interpreting with language dysfluent deaf clients. Journal of Interpretation. 2011;21(1):21-36.

7. Leigh IW, Pollard RQ Jr. Mental health and deaf adults. In: Marschark M, Spencer PE, eds. Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education. Vol 1. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2011:214-226.

8. Øhre B, von Tezchner S, Falkum E. Deaf adults and mental health: A review of recent research on the prevalence and distribution of psychiatric symptoms and disorders in the prelingually deaf adult population. International Journal on Mental Health and Deafness. 2011;1(1):3-22.

9. Appleford J. Clinical activity within a specialist mental health service for deaf people: comparison with a general psychiatric service. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27(10): 375-377.

10. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Inpatient psychiatric treatment of deaf adults: demographic and diagnostic comparisons with hearing inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):196-199.

11. Black PA, Glickman NS. Demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, and other characteristics of North American deaf and hard-of-hearing inpatients. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2006; 11(3):303-321.

12. Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall R, et al. Hearing impairment and psychosis revisited. Schizophr Res. 2005; 76(1):99-103.

13. Steinberg AG, Barnett S, Meador HE, et al. Health care system accessibility. Experiences and perceptions of deaf people. J Gen Inter Med. 2006;21(3):260-266.

14. Paijmans R, Cromwell J, Austen S. Do profoundly prelingually deaf patients with psychosis really hear voices? Am Ann Deaf. 2006;151(1):42-48.

15. Atkinson JR. The perceptual characteristics of voice-hallucinations in deaf people: insights into the nature of subvocal thought and sensory feedback loops. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):701-708.

16. Trumbetta SL, Bonvillian JD, Siedlecki T, et al. Language-related symptoms in persons with schizophrenia and how deaf persons may manifest these symptoms. Sign Language Studies. 2001;1(3):228-253.