User login

The story

SJ was a 66-year-old woman with a history of ulcerative colitis (UC) who was recently status post laparoscopic proctocolectomy with ileoanal J pouch and diverting ileostomy 2 weeks ago at Hospital A. At the time of her surgical discharge, she was tolerating an oral diet, but over the next 2 weeks her oral intake declined, she reported feeling light-headed with movement, and she had an increase in abdominal pain despite oral analgesia. SJ was at her surgical follow-up appointment when she passed out in the waiting room. She awoke spontaneously, but she was hypotensive and was taken by ambulance to the emergency room of Hospital B. On examination SJ was very orthostatic. She had blood drawn, and she had an ECG, an abdominal radiograph, and a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed. Her ECG and abdominal imaging were unremarkable. She was found to have an elevated lipase (910 U/dL) and low hemoglobin (9.9 mg/dL), although her anemia was not significantly different from 2 weeks ago. SJ was sent from Hospital B to Hospital C and admitted by Dr. Hospitalist 1 (nighttime, weekend coverage) for dehydration and possible pancreatitis. Dr. Hospitalist 1 initiated intravenous fluids and ordered an ultrasound of the abdomen. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices were ordered for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

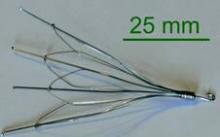

The following morning, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 2 (daytime, weekend coverage). On examination, SJ was noted to have bilateral lower extremity edema. She remained orthostatic despite several liters of saline. Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a CT scan of the chest with a PE protocol along with ultrasonography of the legs. SJ’s morning hemoglobin was 8.4 mg/dL and Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a blood transfusion. The results of the imaging returned the next day and both the CT and lower extremity ultrasounds were normal. However, the abdominal ultrasound ordered by Dr. Hospitalist 1 incidentally identified an inferior vena cava filter (IVCF) with a small amount of adherent clot.

The next day, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 3 (daytime, weekday attending). SJ’s hemoglobin was now 10.4 mg/dL and her lipase was normal. Dr. Hospitalist 3 documented that SJ was doing “better,” and that the plan was to wean IV fluids, work with physical therapy, and discharge soon. But SJ continued to complain of abdominal tightness, burning in her legs, and light-headedness with activity. On hospital day 4, Dr. Hospitalist 3 ordered oral antibiotics for possible leg cellulitis. On hospital day 5, SJ passed out briefly during physical therapy and Dr. Hospitalist 3 increased her IV fluids. Over the next 3 days, Dr. Hospitalist 3 stopped and restarted the IV fluids several times.

On hospital day 8, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 4 (daytime, weekend coverage). SJ remained orthostatic. Dr. Hospitalist 4 ordered a CT of the abdomen to evaluate the IVCF, which identified thrombus material within the IVCF and the entire caudal vena cava, iliac, and femoral vessels. Full-dose anticoagulation was initiated with low-molecular-weight heparin. On hospital day 10, SJ collapsed in physical therapy and lost her pulse. A full code blue response, including systemic TPA administration, failed to revive her and she was pronounced dead. An autopsy was performed and determined pulmonary embolism as the cause of death.

Complaint

SJ’s husband had difficulty reconciling the fact that SJ died so recently after her surgical discharge and that she had been considered “well on her way” to a full recovery. The case was referred to an attorney and subsequent review supported medical negligence and a complaint was filed. The complaint alleged that the Hospitalists (specifically 1, 2, and 3) failed to recognize SJ’s increased risk for thrombosis, failed to diagnose her IVC obstruction, and failed to initiate appropriate treatment in the form of therapeutic anticoagulation. Had the standard of care been followed, the complaint alleged, SJ would not have died.

Scientific principles

Inferior vena cava obstruction has been reported in 3%-30% of patients following IVC filter placement related to new local thrombus formation, thrombogenicity of the device, trapped embolus, or extension of a more distal DVT cephalad. Patients with inferior vena caval thrombosis (IVCT) may present with a spectrum of signs and symptoms and this variability is a significant part of the challenge of diagnosis. The classic presentation of IVCT includes bilateral lower extremity edema with dilated, visible superficial abdominal veins.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The Hospitalists defended themselves by providing reasonable alternatives to the actual diagnosis. SJ had a new ileostomy and orthostasis is common in such patients. Yet SJ did not have documented high stoma outputs and her electrolytes and renal function were inconsistent with hypovolemia.

Defense experts also pointed to SJ’s anemia and orthostasis and opined that anticoagulation would be contraindicated until hemorrhage could be ruled out. Yet SJ’s anemia was not significantly different from her surgical discharge and SJ was on anticoagulant DVT prophylaxis her entire surgical hospitalization with even lower levels of hemoglobin.

Plaintiff experts asserted that the Hospitalists should have contacted SJ’s colorectal surgeon if they were reluctant to use anticoagulants to further inform the risks and benefits. Ultimately, the defense had little explanation for the Hospitalists’ collective failure to follow-up on the abdominal ultrasound that demonstrated a small amount of adherent clot.

Conclusion

SJ was at two different hospitals and had four different Hospitalist s in 10 days.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 never saw the radiology films from Hospital B that showed an IVCF. When Dr. Hospitalist 2 began caring for SJ, he was unaware that SJ even had an IVCF or that she had a prior history of PE. Over the weekend, Dr. Hospitalist 2 did not access the labs from Hospital A to see if SJ’s anemia was new or not. Dr. Hospitalist 3 did not know that Dr. Hospitalist 1 ordered an abdominal ultrasound on admission and because the result was not flagged as “abnormal” the small adherent clot on the IVCF was not integrated into SJ’s clinical presentation.

All Hospitalist groups struggle to provide continuity in a system of discontinuity. In this case, important details were missed and it led to a delay in diagnosis and ultimately treatment.

This case was settled for an undisclosed amount on behalf of the plaintiff.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at eHospitalist news.com/Lessons.

The story

SJ was a 66-year-old woman with a history of ulcerative colitis (UC) who was recently status post laparoscopic proctocolectomy with ileoanal J pouch and diverting ileostomy 2 weeks ago at Hospital A. At the time of her surgical discharge, she was tolerating an oral diet, but over the next 2 weeks her oral intake declined, she reported feeling light-headed with movement, and she had an increase in abdominal pain despite oral analgesia. SJ was at her surgical follow-up appointment when she passed out in the waiting room. She awoke spontaneously, but she was hypotensive and was taken by ambulance to the emergency room of Hospital B. On examination SJ was very orthostatic. She had blood drawn, and she had an ECG, an abdominal radiograph, and a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed. Her ECG and abdominal imaging were unremarkable. She was found to have an elevated lipase (910 U/dL) and low hemoglobin (9.9 mg/dL), although her anemia was not significantly different from 2 weeks ago. SJ was sent from Hospital B to Hospital C and admitted by Dr. Hospitalist 1 (nighttime, weekend coverage) for dehydration and possible pancreatitis. Dr. Hospitalist 1 initiated intravenous fluids and ordered an ultrasound of the abdomen. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices were ordered for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

The following morning, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 2 (daytime, weekend coverage). On examination, SJ was noted to have bilateral lower extremity edema. She remained orthostatic despite several liters of saline. Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a CT scan of the chest with a PE protocol along with ultrasonography of the legs. SJ’s morning hemoglobin was 8.4 mg/dL and Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a blood transfusion. The results of the imaging returned the next day and both the CT and lower extremity ultrasounds were normal. However, the abdominal ultrasound ordered by Dr. Hospitalist 1 incidentally identified an inferior vena cava filter (IVCF) with a small amount of adherent clot.

The next day, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 3 (daytime, weekday attending). SJ’s hemoglobin was now 10.4 mg/dL and her lipase was normal. Dr. Hospitalist 3 documented that SJ was doing “better,” and that the plan was to wean IV fluids, work with physical therapy, and discharge soon. But SJ continued to complain of abdominal tightness, burning in her legs, and light-headedness with activity. On hospital day 4, Dr. Hospitalist 3 ordered oral antibiotics for possible leg cellulitis. On hospital day 5, SJ passed out briefly during physical therapy and Dr. Hospitalist 3 increased her IV fluids. Over the next 3 days, Dr. Hospitalist 3 stopped and restarted the IV fluids several times.

On hospital day 8, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 4 (daytime, weekend coverage). SJ remained orthostatic. Dr. Hospitalist 4 ordered a CT of the abdomen to evaluate the IVCF, which identified thrombus material within the IVCF and the entire caudal vena cava, iliac, and femoral vessels. Full-dose anticoagulation was initiated with low-molecular-weight heparin. On hospital day 10, SJ collapsed in physical therapy and lost her pulse. A full code blue response, including systemic TPA administration, failed to revive her and she was pronounced dead. An autopsy was performed and determined pulmonary embolism as the cause of death.

Complaint

SJ’s husband had difficulty reconciling the fact that SJ died so recently after her surgical discharge and that she had been considered “well on her way” to a full recovery. The case was referred to an attorney and subsequent review supported medical negligence and a complaint was filed. The complaint alleged that the Hospitalists (specifically 1, 2, and 3) failed to recognize SJ’s increased risk for thrombosis, failed to diagnose her IVC obstruction, and failed to initiate appropriate treatment in the form of therapeutic anticoagulation. Had the standard of care been followed, the complaint alleged, SJ would not have died.

Scientific principles

Inferior vena cava obstruction has been reported in 3%-30% of patients following IVC filter placement related to new local thrombus formation, thrombogenicity of the device, trapped embolus, or extension of a more distal DVT cephalad. Patients with inferior vena caval thrombosis (IVCT) may present with a spectrum of signs and symptoms and this variability is a significant part of the challenge of diagnosis. The classic presentation of IVCT includes bilateral lower extremity edema with dilated, visible superficial abdominal veins.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The Hospitalists defended themselves by providing reasonable alternatives to the actual diagnosis. SJ had a new ileostomy and orthostasis is common in such patients. Yet SJ did not have documented high stoma outputs and her electrolytes and renal function were inconsistent with hypovolemia.

Defense experts also pointed to SJ’s anemia and orthostasis and opined that anticoagulation would be contraindicated until hemorrhage could be ruled out. Yet SJ’s anemia was not significantly different from her surgical discharge and SJ was on anticoagulant DVT prophylaxis her entire surgical hospitalization with even lower levels of hemoglobin.

Plaintiff experts asserted that the Hospitalists should have contacted SJ’s colorectal surgeon if they were reluctant to use anticoagulants to further inform the risks and benefits. Ultimately, the defense had little explanation for the Hospitalists’ collective failure to follow-up on the abdominal ultrasound that demonstrated a small amount of adherent clot.

Conclusion

SJ was at two different hospitals and had four different Hospitalist s in 10 days.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 never saw the radiology films from Hospital B that showed an IVCF. When Dr. Hospitalist 2 began caring for SJ, he was unaware that SJ even had an IVCF or that she had a prior history of PE. Over the weekend, Dr. Hospitalist 2 did not access the labs from Hospital A to see if SJ’s anemia was new or not. Dr. Hospitalist 3 did not know that Dr. Hospitalist 1 ordered an abdominal ultrasound on admission and because the result was not flagged as “abnormal” the small adherent clot on the IVCF was not integrated into SJ’s clinical presentation.

All Hospitalist groups struggle to provide continuity in a system of discontinuity. In this case, important details were missed and it led to a delay in diagnosis and ultimately treatment.

This case was settled for an undisclosed amount on behalf of the plaintiff.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at eHospitalist news.com/Lessons.

The story

SJ was a 66-year-old woman with a history of ulcerative colitis (UC) who was recently status post laparoscopic proctocolectomy with ileoanal J pouch and diverting ileostomy 2 weeks ago at Hospital A. At the time of her surgical discharge, she was tolerating an oral diet, but over the next 2 weeks her oral intake declined, she reported feeling light-headed with movement, and she had an increase in abdominal pain despite oral analgesia. SJ was at her surgical follow-up appointment when she passed out in the waiting room. She awoke spontaneously, but she was hypotensive and was taken by ambulance to the emergency room of Hospital B. On examination SJ was very orthostatic. She had blood drawn, and she had an ECG, an abdominal radiograph, and a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed. Her ECG and abdominal imaging were unremarkable. She was found to have an elevated lipase (910 U/dL) and low hemoglobin (9.9 mg/dL), although her anemia was not significantly different from 2 weeks ago. SJ was sent from Hospital B to Hospital C and admitted by Dr. Hospitalist 1 (nighttime, weekend coverage) for dehydration and possible pancreatitis. Dr. Hospitalist 1 initiated intravenous fluids and ordered an ultrasound of the abdomen. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices were ordered for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

The following morning, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 2 (daytime, weekend coverage). On examination, SJ was noted to have bilateral lower extremity edema. She remained orthostatic despite several liters of saline. Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a CT scan of the chest with a PE protocol along with ultrasonography of the legs. SJ’s morning hemoglobin was 8.4 mg/dL and Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a blood transfusion. The results of the imaging returned the next day and both the CT and lower extremity ultrasounds were normal. However, the abdominal ultrasound ordered by Dr. Hospitalist 1 incidentally identified an inferior vena cava filter (IVCF) with a small amount of adherent clot.

The next day, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 3 (daytime, weekday attending). SJ’s hemoglobin was now 10.4 mg/dL and her lipase was normal. Dr. Hospitalist 3 documented that SJ was doing “better,” and that the plan was to wean IV fluids, work with physical therapy, and discharge soon. But SJ continued to complain of abdominal tightness, burning in her legs, and light-headedness with activity. On hospital day 4, Dr. Hospitalist 3 ordered oral antibiotics for possible leg cellulitis. On hospital day 5, SJ passed out briefly during physical therapy and Dr. Hospitalist 3 increased her IV fluids. Over the next 3 days, Dr. Hospitalist 3 stopped and restarted the IV fluids several times.

On hospital day 8, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 4 (daytime, weekend coverage). SJ remained orthostatic. Dr. Hospitalist 4 ordered a CT of the abdomen to evaluate the IVCF, which identified thrombus material within the IVCF and the entire caudal vena cava, iliac, and femoral vessels. Full-dose anticoagulation was initiated with low-molecular-weight heparin. On hospital day 10, SJ collapsed in physical therapy and lost her pulse. A full code blue response, including systemic TPA administration, failed to revive her and she was pronounced dead. An autopsy was performed and determined pulmonary embolism as the cause of death.

Complaint

SJ’s husband had difficulty reconciling the fact that SJ died so recently after her surgical discharge and that she had been considered “well on her way” to a full recovery. The case was referred to an attorney and subsequent review supported medical negligence and a complaint was filed. The complaint alleged that the Hospitalists (specifically 1, 2, and 3) failed to recognize SJ’s increased risk for thrombosis, failed to diagnose her IVC obstruction, and failed to initiate appropriate treatment in the form of therapeutic anticoagulation. Had the standard of care been followed, the complaint alleged, SJ would not have died.

Scientific principles

Inferior vena cava obstruction has been reported in 3%-30% of patients following IVC filter placement related to new local thrombus formation, thrombogenicity of the device, trapped embolus, or extension of a more distal DVT cephalad. Patients with inferior vena caval thrombosis (IVCT) may present with a spectrum of signs and symptoms and this variability is a significant part of the challenge of diagnosis. The classic presentation of IVCT includes bilateral lower extremity edema with dilated, visible superficial abdominal veins.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The Hospitalists defended themselves by providing reasonable alternatives to the actual diagnosis. SJ had a new ileostomy and orthostasis is common in such patients. Yet SJ did not have documented high stoma outputs and her electrolytes and renal function were inconsistent with hypovolemia.

Defense experts also pointed to SJ’s anemia and orthostasis and opined that anticoagulation would be contraindicated until hemorrhage could be ruled out. Yet SJ’s anemia was not significantly different from her surgical discharge and SJ was on anticoagulant DVT prophylaxis her entire surgical hospitalization with even lower levels of hemoglobin.

Plaintiff experts asserted that the Hospitalists should have contacted SJ’s colorectal surgeon if they were reluctant to use anticoagulants to further inform the risks and benefits. Ultimately, the defense had little explanation for the Hospitalists’ collective failure to follow-up on the abdominal ultrasound that demonstrated a small amount of adherent clot.

Conclusion

SJ was at two different hospitals and had four different Hospitalist s in 10 days.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 never saw the radiology films from Hospital B that showed an IVCF. When Dr. Hospitalist 2 began caring for SJ, he was unaware that SJ even had an IVCF or that she had a prior history of PE. Over the weekend, Dr. Hospitalist 2 did not access the labs from Hospital A to see if SJ’s anemia was new or not. Dr. Hospitalist 3 did not know that Dr. Hospitalist 1 ordered an abdominal ultrasound on admission and because the result was not flagged as “abnormal” the small adherent clot on the IVCF was not integrated into SJ’s clinical presentation.

All Hospitalist groups struggle to provide continuity in a system of discontinuity. In this case, important details were missed and it led to a delay in diagnosis and ultimately treatment.

This case was settled for an undisclosed amount on behalf of the plaintiff.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at eHospitalist news.com/Lessons.