User login

CASE Light-headed

Mr. M, age 73, is a retired project manager who feels light-headed while walking his dog, causing him to go to the emergency department. His history is significant for hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), 3-vessel coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), hyperlipidemia, erectile dysfunction, open-angle glaucoma, hemiretinal vein occlusion, symptoms suggesting rapid eye-movement behavior disorder (RBD), and major depressive disorder (MDD).

The psychiatry consultation-liaison service is asked to help manage Mr. M’s psychiatric medications in the context of orthostatic hypotension and cognitive deficits.

What could be causing Mr. M’s symptoms?

a) drug adverse effect

b) progressive cardiovascular disease

c) MDD

d) all of the above

HISTORY Depression, heart disease

15 years ago. Mr. M experienced his first major depressive episode. His primary care physician (PCP) commented on a history of falling asleep while driving and 1 episode of sleepwalking. His depression was treated to remission with fluoxetine and methylphenidate (dosages were not recorded), the latter also addressed his falling asleep while driving.

5 years ago. Mr. M had another depressive episode characterized by anxiety, difficulty sleeping, and irritability. He also described chest pain; a cardiac work-up revealed extensive CAD, which led to 3-vessel CABG later that year. He also reported dizziness upon standing, which was treated with compression stockings and an increase in sodium intake.

Mr. M continued to express feelings of depression. His cardiologist started him on paroxetine, 10 mg/d, which he took for 2 months and decided to stop because he felt better. He declined psychiatric referral.

4 years ago. Mr. M’s PCP referred him to a psychiatrist for depressed mood, anhedonia, decreased appetite, decreased energy, and difficulty concentrating. Immediate and delayed recall were found to be intact. The psychiatrist diagnosed MDD and Mr. M started escitalopram, 5 mg/d, titrated to 15 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d.

After starting treatment, Mr. M reported decreased libido. Sustained-release bupropion, 150 mg/d, was added to boost the effects of escitalopram and counteract sexual side effects.

At follow-up, Mr. M reported that his depressive symptoms and libido had improved, but that he had been experiencing unsteady gait when getting out of his car, which he had been noticing “for a while”—before he began trazodone. Mr. M was referred to his PCP, who attributed his symptoms to orthostasis. No treatment was indicated at the time because Mr. M’s lightheadedness had resolved.

3 years ago. Mr. M reported a syncopal attack and continued “dizziness.” His PCP prescribed fludrocortisone, 0.1 mg/d, later to be dosed 0.2 mg/d, and symptoms improved.

Although Mr. M had a history of orthostatic hypotension, he was later noted to have supine hypertension. Mr. M’s PCP was concerned that fludrocortisone could be causing the supine hypertension but that decreasing the dosage would cause his orthostatic hypotension to return.

The PCP also was concerned that the psychiatric medications (escitalopram, trazodone, and bupropion) could be causing orthostasis. There was discussion among Mr. M, his PCP, and his psychiatrist of stopping the psychotropics to see if the symptoms would remit; however, because of concerns about Mr. M’s depression, the medications were continued. Mr. M monitored his blood pressure at home and was referred to a neurologist for work-up of potential autonomic dysfunction.

Shortly afterward, Mr. M reported intermittent difficulty keeping track of his thoughts and finishing sentences. His psychiatrist ordered an MRI, which showed chronic small vessel ischemic changes, and started him on donepezil, 5 mg/d.

Neuropsychological testing revealed decreased processing speed and poor recognition memory; otherwise, results showed above-average intellectual ability and average or above-average performance in measures of language, attention, visuospatial/constructional functions, and executive functions—a pattern typically attributable to psychogenic factors, such as depression.

Mr. M reported to his neurologist that he forgets directions while driving but can focus better if he makes a conscious effort. Physical exam was significant hypotension; flat affect; deficits in concentration and short-term recall; mild impairment of Luria motor sequence (composed of a go/no-go and a reciprocal motor task); and vertical and horizontal saccades.1

Mr. M consulted with an ophthalmologist for anterior iridocyclitis and ocular hypertension, which was controlled with travoprost. He continued to experience trouble with his vision and was given a diagnosis of right inferior hemiretinal vein occlusion, macular edema, and suspected glaucoma. Subsequent notes recorded a history of Posner-Schlossman syndrome (a disease characterized by recurrent attacks of increased intraocular pressure in 1 eye with concomitant anterior chamber inflammation). His vision deteriorated until he was diagnosed with ocular hypertension, open-angle glaucoma, and dermatochalasis.

The authors’ observations

Involvement of multiple specialties in a patient’s care brings to question one’s philosophy on medical diagnosis. Interdisciplinary communication would seem to promote the principle of diagnostic parsimony, or Occam’s razor, which suggests a unifying diagnosis to explain all of the patient’s symptoms. Lack of communication might favor Hickam’s dictum, which states that “patients can have as many diseases as they damn well please.”

HISTORY Low energy, forgetfulness

2 years ago. Mr. M noticed low energy and motivation. He continued to work full-time but thought that it was taking him longer to get work done. He was tapered off escitalopram and started on desvenlafaxine, 50 mg/d; donepezil was increased to 10 mg/d.

The syncopal episodes resolved but blood pressure measured at home averaged 150/70 mm Hg. Mr. M was advised to decrease fludrocortisone from 0.2 mg/d to 0.1 mg/d. He tolerated the change and blood pressure measured at home dropped on average to 120 to 130/70 mm Hg.

1 year ago. Mr. M reported that his memory loss had become worse. He perceived having more stress because of forgetfulness and visual difficulties, which had led him to stop driving at night.

At a follow-up appointment with his psychiatrist, Mr. M reported that, first, he had not tapered escitalopram as discussed and, second, he forgot to increase the dosage of desvenlafaxine. A home blood pressure log revealed consistent hypotension; the psychiatrist was concerned that hypotension could be the cause of concentration difficulties and malaise. The psychiatrist advised Mr. M to follow-up with his PCP and neurologist.

Current admission. Shortly after the visit to the psychiatrist, Mr. M presented to the emergency department for increased syncopal events. Work-up was negative for a cardiac cause. A cosyntropin stimulation test was negative, showing that adrenal insufficiency did not cause his orthostatic hypotension. Chart review showed he had been having blood pressure problems for many years, independent of antidepressants. Physical exam revealed lower extremity ataxia and a bilateral extensor plantar reflex.

What diagnosis explains Mr. M’s symptoms?

a) Parkinson’s disease

b) multiple system atrophy (MSA)

c) depression due to a general medical condition

d) dementia

The authors’ observations

MSA, previously referred to as Shy-Drager syndrome, is a rare, rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disorder with an estimated prevalence of 3.7 cases for every 100,000 people worldwide.2 MSA primarily affects middle-aged patients; because it has no cure, most patients die in 7 to 10 years.3

MSA has 2 clinical variants4,5:

• parkinsonian type (MSA-P), characterized by striatonigral degeneration and increased spasticity

• cerebellar type (MSA-C), characterized by more autonomic dysfunction.

MSA has a range of symptoms, making it a challenging diagnosis (Table).6 Although psychiatric symptoms are not part of the diagnostic criteria, they can aid in its diagnosis. In Mr. M’s case, depression, anxiety, orthostatic hypotension, and ataxia support a diagnosis of MSA.

Gilman et al6 delineated 3 diagnostic categories for MSA: definite MSA, probable MSA, and possible MSA. Clinical criteria shared by the 3 diagnostic categories are sporadic and progressive onset after age 30.

Definite MSA requires “neuropathological findings of widespread and abundant CNS alpha-synuclein-positive glial cytoplasmic inclusions,” along with “neurodegenerative changes in striatonigral or olivopontocerebellar structures” at autopsy.6

Probable MSA. Without autopsy findings required for definite MSA, the next most specific diagnostic category is probable MSA. Probable MSA also specifies that the patient show either autonomic failure involving urinary incontinence—this includes erectile dysfunction in men—or, if autonomic failure is absent, orthostatic hypotension within 3 minutes of standing by at least 30 mm Hg systolic pressure or 15 mm Hg diastolic pressure.

Possible MSA has less stringent criteria for orthostatic hypotension. The category includes patients who have only 1 symptom that suggests autonomic failure. Criteria for possible MSA include parkinsonism or a cerebellar syndrome in addition to symptoms of MSA listed in the Table, whereas probable MSA has specific criteria of either a poorly levodopa-responsive parkinsonism (MSA-P) or a cerebellar syndrome (MSA-C). In addition to having parkinsonism or a cerebellar syndrome, and 1 sign of autonomic failure or orthostatic hypotension, patients also must have ≥1 additional feature to be assigned a diagnosis of possible MSA, including:

• rapidly progressive parkinsonism

• poor response to levodopa

• postural instability within 3 years of motor onset

• gait ataxia, cerebellar dysarthria, limb ataxia, or cerebellar oculomotor dysfunction

• dysphagia within 5 years of motor onset

• atrophy on MRI of putamen, middle cerebellar peduncle, pons, or cerebellum

• hypometabolism on fluorodeoxyglucose- PET in putamen, brainstem, or cerebellum.6

Diagnosing MSA can be challenging because its features are similar to those of many other disorders. Nonetheless, Gilman et al6 lists specific criteria for probable MSA, including autonomic dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, and either parkinsonism or cerebellar syndrome symptoms. Although a definite MSA diagnosis only can be made by postmortem brain specimen analysis, Osaki et al7 found that a probable MSA diagnosis has a positive predictive value of 92% with a sensitivity of 22% for definite MSA.

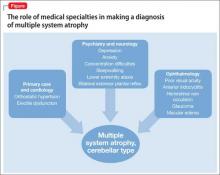

Mr. M’s symptoms were consistent with a diagnosis of probable MSA, cerebellar type (Figure).

Psychiatric manifestations of MSA

There are a few case reports of depression identified early in patients who were later given a diagnosis of MSA.8

Depression. In a study by Benrud-Larson et al9 (N = 99), 49% of patients who had MSA reported moderate or severe depression, as indicated by a score of ≥17 on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); 80% reported at least mild depression (BDI ≥10, mean 17.0, standard deviation, 8.7).

In a similar study, by Balas et al,10 depression was reported as a common symptom and was statistically significant in MSA-P patients compared with controls (P = .013).

Anxiety, another symptom that was reported by Mr. M, is another psychiatric manifestation described by Balas et al10 and Chang et al.11 Balas et al10 noted that MSA-C and MSA-P patients had significantly more state anxiety (P = .009 and P = .022, respectively) compared with controls, although Chang et al11 noted higher anxiety scores in MSA-C patients compared with controls and MSA-P patients (P < .01).

Balas et al10 hypothesized that anxiety and depression contribute to cognitive decline; their study showed that MSA-C patients had difficulty learning new verbal information (P < .022) and controlling attention (P < .023). Mr. M exhibited some of these cognitive difficulties in his reports of losing track of conversations, forgetting the topic of a conversation when speaking, trouble focusing, and difficulty concentrating when driving.

Mr. M had depression and anxiety well before onset of autonomic dysfunction (orthostatic hypotension and erectile dysfunction), which eventually led to an MSA diagnosis. Psychiatrists should understand additional manifestations of MSA so that they can use psychiatric symptoms to identify these conditions in their patients. One of the most well-known and early manifestations of MSA is autonomic dysfunction; among men, another early sign is erectile dysfunction.6 Our patient also exhibited other less well-known symptoms linked to MSA and autonomic dysregulation, including RBD and ocular symptoms (iridocyclitis, glaucoma, decreased visual acuity).

Rapid eye-movement behavior disorder. Psychiatrists should consider screening for RBD during assessment of sleep problems. Identifying RBD is important because early studies have shown a strong association between RBD and development of a neurodegenerative disorder. Mr. M’s clinicians did not consider RBD, although his symptoms of sleepwalking and falling asleep while driving suggest a possible diagnosis. Also, considering this diagnosis would aid in diagnosing a synucleinopathy disorder because a higher incidence of RBD was noted in patients who developed synucleinopathy disorders (eg, Parkinson’s disease [PD] and dementia with Lewy bodies [DLB]) compared with patients who developed non-synucleinopathies (eg, frontotemporal dementia, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, mild cognitive impairment, primary progressive aphasia, and posterior cortical atrophy) or tauopathies (eg, Alzheimer’s disease).12

Zanigni et al13 reported similar findings in a later study that classified patients with RBD as having idiopathic RBD (IRBD) or RBD secondary to an underlying neurodegenerative disorder, particularly an α-synucleinopathy: PD, MSA, and DLB. Most IRBD patients developed 1 of the above mentioned neurodegenerative disorders as long as 10 years after a diagnosis of RBD.

In a study by Iranzo et al,14 patients with MSA were noted to have more severe RBD compared with PD patients. Severity is illustrated by greater periodic leg movements during sleep (P = .001), less total sleep time (P = .023), longer sleep onset latency (P = .023), and a higher percentage of REM sleep without atonia (RSWA, P = .001). McCarter et al15 also noted a higher incidence of RSWA in patients with MSA.

Patients with MSA might therefore be more likely to exhibit difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep and as having RSWA years before the MSA diagnosis.

Several psychotropics (eg, first-generation antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines, carbamazepine, topiramate, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can cause adverse ocular effects, such as closed-angle glaucoma in predisposed persons and retinopathy.16 Therefore, it is important for psychiatrists to ask about ocular symptoms because they might be an early sign of autonomic dysfunction.

Posner and Schlossman17 theorized a causal relationship between autonomic dysfunction and ocular diseases after studying a group of patients who had intermittent unilateral attacks of iridocyclitis and glaucoma (now known as Posner-Schlossman syndrome). They hypothesized that a central cause in the hypothalamus, combined with underlying autonomic dysregulation, could cause the intermittent attacks.

Gherghel et al18 noted a significant difference in ocular blood flow and blood pressure in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) compared with controls. Patients with POAG did not show an increase in blood pressure or ocular blood flow when challenged by cold water, which should have increased their sympathetic activity. Gherghel et al18 concluded that this indicated possible systemic autonomic dysfunction in patients with POAG. In a study by Fischer et al,19 MSA patients also were noted to have significant loss of nasal retinal nerve fiber layer thickness vs controls (P < .05), leading to decreased peripheral vision sensitivity.

Bottom Line

Although psychiatric symptoms are not part of the diagnostic criteria for multiple system atrophy (MSA), they may serve as a clue to consider when they occur with other MSA symptoms. Evaluate the importance of psychiatric symptoms in terms of the whole picture of the patient. Although the diagnosis might not alter the patient’s course, it can allow family members to understand the patient’s condition and prepare for complications that will arise.

Related Resources

• The MSA Coalition. www.multiplesystematrophy.org.

• National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Multiple system atrophy fact sheet. www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/msa/detailmsa.htm.

• Wenning GK, Fanciulli A, eds. Multiple system atrophy. Vienna, Austria: Springer-Verlag Wien; 2014.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq Paroxetine • Paxil

Donepezil • Aricept Travoprost • Travatan

Escitalopram • Lexapro Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Fludrocortisone • Florinef Topiramate • Topamax

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Weiner MF, Hynan LS, Rossetti H, et al. Luria’s three-step test: what is it and what does it tell us? Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(10):1602-1606.

2. Orphanet Report Series. Prevalence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/ cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_ alphabetical_list.pdf. Published May 2014. Accessed May 27, 2015.

3. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Multiple system atrophy with orthostatic hypotension information page. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/ msa_orthostatic_hypotension/msa_orthostatic_ hypotension.htm?css=print. Updated December 5, 2013. Accessed May 27, 2015.

4. Flaherty AW, Rost NS. The Massachusetts Hospital handbook of neurology. 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Boston, MA; 2007:79.

5. Hemingway J, Franco K, Chmelik E. Shy-Drager syndrome: multisystem atrophy with comorbid depression. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(1):73-76.

6. Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008;71(9):670-676.

7. Osaki Y, Wenning GK, Daniel SE, et al. Do published criteria improve clinical diagnostic accuracy in multiple system atrophy? Neurology. 2002;59(10):1486-1491.

8. Goto K, Ueki A, Shimode H, et al. Depression in multiple system atrophy: a case report. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54(4):507-511.

9. Benrud-Larson LM, Sandroni P, Schrag A, et al. Depressive symptoms and life satisfaction in patients with multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord. 2005;20(8):951-957.

10. Balas M, Balash Y, Giladi N, et al. Cognition in multiple system atrophy: neuropsychological profile and interaction with mood. J Neural Transm. 2010;117(3):369-375.

11. Chang CC, Chang YY, Chang WN, et al. Cognitive deficits in multiple system atrophy correlate with frontal atrophy and disease duration. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(10):1144-1150.

12. Boeve BF, Silber MH, Parisi JE, et al. Synucleinopathy pathology and REM sleep behavior disorder plus dementia or parkinsonism. Neurology. 2003;61(1):40-45.

13. Zanigni S, Calandra-Buonaura G, Grimaldi D, et al. REM behaviour disorder and neurodegenerative diseases. Sleep Med. 2011;12(suppl 2):S54-S58.

14. Iranzo A, Santamaria J, Rye DB, et al. Characteristics of idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder and that associated with MSA and PD. Neurology. 2005;65(2):247-252.

15. McCarter SJ, St. Louis EK, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia as early manifestation of degenerative neurological disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12(2):182-192.

16. Richa S, Yazbek JC. Ocular adverse effects of common psychotropic agents: a review. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(6):501-526.

17. Posner A, Schlossman A. Syndrome of unilateral recurrent attacks of glaucoma with cyclitic symptoms. Arch Ophthal. 1948;39(4):517-535.

18. Gherghel D, Hosking SL, Cunliffe IA. Abnormal systemic and ocular vascular response to temperature provocation in primary open-angle glaucoma patients: a case for autonomic failure? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(10):3546-3554.

19. Fischer MD, Synofzik M, Kernstock C, et al. Decreased retinal sensitivity and loss of retinal nerve fibers in multiple system atrophy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Opthalmol. 2013;251(1):235-241.

CASE Light-headed

Mr. M, age 73, is a retired project manager who feels light-headed while walking his dog, causing him to go to the emergency department. His history is significant for hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), 3-vessel coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), hyperlipidemia, erectile dysfunction, open-angle glaucoma, hemiretinal vein occlusion, symptoms suggesting rapid eye-movement behavior disorder (RBD), and major depressive disorder (MDD).

The psychiatry consultation-liaison service is asked to help manage Mr. M’s psychiatric medications in the context of orthostatic hypotension and cognitive deficits.

What could be causing Mr. M’s symptoms?

a) drug adverse effect

b) progressive cardiovascular disease

c) MDD

d) all of the above

HISTORY Depression, heart disease

15 years ago. Mr. M experienced his first major depressive episode. His primary care physician (PCP) commented on a history of falling asleep while driving and 1 episode of sleepwalking. His depression was treated to remission with fluoxetine and methylphenidate (dosages were not recorded), the latter also addressed his falling asleep while driving.

5 years ago. Mr. M had another depressive episode characterized by anxiety, difficulty sleeping, and irritability. He also described chest pain; a cardiac work-up revealed extensive CAD, which led to 3-vessel CABG later that year. He also reported dizziness upon standing, which was treated with compression stockings and an increase in sodium intake.

Mr. M continued to express feelings of depression. His cardiologist started him on paroxetine, 10 mg/d, which he took for 2 months and decided to stop because he felt better. He declined psychiatric referral.

4 years ago. Mr. M’s PCP referred him to a psychiatrist for depressed mood, anhedonia, decreased appetite, decreased energy, and difficulty concentrating. Immediate and delayed recall were found to be intact. The psychiatrist diagnosed MDD and Mr. M started escitalopram, 5 mg/d, titrated to 15 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d.

After starting treatment, Mr. M reported decreased libido. Sustained-release bupropion, 150 mg/d, was added to boost the effects of escitalopram and counteract sexual side effects.

At follow-up, Mr. M reported that his depressive symptoms and libido had improved, but that he had been experiencing unsteady gait when getting out of his car, which he had been noticing “for a while”—before he began trazodone. Mr. M was referred to his PCP, who attributed his symptoms to orthostasis. No treatment was indicated at the time because Mr. M’s lightheadedness had resolved.

3 years ago. Mr. M reported a syncopal attack and continued “dizziness.” His PCP prescribed fludrocortisone, 0.1 mg/d, later to be dosed 0.2 mg/d, and symptoms improved.

Although Mr. M had a history of orthostatic hypotension, he was later noted to have supine hypertension. Mr. M’s PCP was concerned that fludrocortisone could be causing the supine hypertension but that decreasing the dosage would cause his orthostatic hypotension to return.

The PCP also was concerned that the psychiatric medications (escitalopram, trazodone, and bupropion) could be causing orthostasis. There was discussion among Mr. M, his PCP, and his psychiatrist of stopping the psychotropics to see if the symptoms would remit; however, because of concerns about Mr. M’s depression, the medications were continued. Mr. M monitored his blood pressure at home and was referred to a neurologist for work-up of potential autonomic dysfunction.

Shortly afterward, Mr. M reported intermittent difficulty keeping track of his thoughts and finishing sentences. His psychiatrist ordered an MRI, which showed chronic small vessel ischemic changes, and started him on donepezil, 5 mg/d.

Neuropsychological testing revealed decreased processing speed and poor recognition memory; otherwise, results showed above-average intellectual ability and average or above-average performance in measures of language, attention, visuospatial/constructional functions, and executive functions—a pattern typically attributable to psychogenic factors, such as depression.

Mr. M reported to his neurologist that he forgets directions while driving but can focus better if he makes a conscious effort. Physical exam was significant hypotension; flat affect; deficits in concentration and short-term recall; mild impairment of Luria motor sequence (composed of a go/no-go and a reciprocal motor task); and vertical and horizontal saccades.1

Mr. M consulted with an ophthalmologist for anterior iridocyclitis and ocular hypertension, which was controlled with travoprost. He continued to experience trouble with his vision and was given a diagnosis of right inferior hemiretinal vein occlusion, macular edema, and suspected glaucoma. Subsequent notes recorded a history of Posner-Schlossman syndrome (a disease characterized by recurrent attacks of increased intraocular pressure in 1 eye with concomitant anterior chamber inflammation). His vision deteriorated until he was diagnosed with ocular hypertension, open-angle glaucoma, and dermatochalasis.

The authors’ observations

Involvement of multiple specialties in a patient’s care brings to question one’s philosophy on medical diagnosis. Interdisciplinary communication would seem to promote the principle of diagnostic parsimony, or Occam’s razor, which suggests a unifying diagnosis to explain all of the patient’s symptoms. Lack of communication might favor Hickam’s dictum, which states that “patients can have as many diseases as they damn well please.”

HISTORY Low energy, forgetfulness

2 years ago. Mr. M noticed low energy and motivation. He continued to work full-time but thought that it was taking him longer to get work done. He was tapered off escitalopram and started on desvenlafaxine, 50 mg/d; donepezil was increased to 10 mg/d.

The syncopal episodes resolved but blood pressure measured at home averaged 150/70 mm Hg. Mr. M was advised to decrease fludrocortisone from 0.2 mg/d to 0.1 mg/d. He tolerated the change and blood pressure measured at home dropped on average to 120 to 130/70 mm Hg.

1 year ago. Mr. M reported that his memory loss had become worse. He perceived having more stress because of forgetfulness and visual difficulties, which had led him to stop driving at night.

At a follow-up appointment with his psychiatrist, Mr. M reported that, first, he had not tapered escitalopram as discussed and, second, he forgot to increase the dosage of desvenlafaxine. A home blood pressure log revealed consistent hypotension; the psychiatrist was concerned that hypotension could be the cause of concentration difficulties and malaise. The psychiatrist advised Mr. M to follow-up with his PCP and neurologist.

Current admission. Shortly after the visit to the psychiatrist, Mr. M presented to the emergency department for increased syncopal events. Work-up was negative for a cardiac cause. A cosyntropin stimulation test was negative, showing that adrenal insufficiency did not cause his orthostatic hypotension. Chart review showed he had been having blood pressure problems for many years, independent of antidepressants. Physical exam revealed lower extremity ataxia and a bilateral extensor plantar reflex.

What diagnosis explains Mr. M’s symptoms?

a) Parkinson’s disease

b) multiple system atrophy (MSA)

c) depression due to a general medical condition

d) dementia

The authors’ observations

MSA, previously referred to as Shy-Drager syndrome, is a rare, rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disorder with an estimated prevalence of 3.7 cases for every 100,000 people worldwide.2 MSA primarily affects middle-aged patients; because it has no cure, most patients die in 7 to 10 years.3

MSA has 2 clinical variants4,5:

• parkinsonian type (MSA-P), characterized by striatonigral degeneration and increased spasticity

• cerebellar type (MSA-C), characterized by more autonomic dysfunction.

MSA has a range of symptoms, making it a challenging diagnosis (Table).6 Although psychiatric symptoms are not part of the diagnostic criteria, they can aid in its diagnosis. In Mr. M’s case, depression, anxiety, orthostatic hypotension, and ataxia support a diagnosis of MSA.

Gilman et al6 delineated 3 diagnostic categories for MSA: definite MSA, probable MSA, and possible MSA. Clinical criteria shared by the 3 diagnostic categories are sporadic and progressive onset after age 30.

Definite MSA requires “neuropathological findings of widespread and abundant CNS alpha-synuclein-positive glial cytoplasmic inclusions,” along with “neurodegenerative changes in striatonigral or olivopontocerebellar structures” at autopsy.6

Probable MSA. Without autopsy findings required for definite MSA, the next most specific diagnostic category is probable MSA. Probable MSA also specifies that the patient show either autonomic failure involving urinary incontinence—this includes erectile dysfunction in men—or, if autonomic failure is absent, orthostatic hypotension within 3 minutes of standing by at least 30 mm Hg systolic pressure or 15 mm Hg diastolic pressure.

Possible MSA has less stringent criteria for orthostatic hypotension. The category includes patients who have only 1 symptom that suggests autonomic failure. Criteria for possible MSA include parkinsonism or a cerebellar syndrome in addition to symptoms of MSA listed in the Table, whereas probable MSA has specific criteria of either a poorly levodopa-responsive parkinsonism (MSA-P) or a cerebellar syndrome (MSA-C). In addition to having parkinsonism or a cerebellar syndrome, and 1 sign of autonomic failure or orthostatic hypotension, patients also must have ≥1 additional feature to be assigned a diagnosis of possible MSA, including:

• rapidly progressive parkinsonism

• poor response to levodopa

• postural instability within 3 years of motor onset

• gait ataxia, cerebellar dysarthria, limb ataxia, or cerebellar oculomotor dysfunction

• dysphagia within 5 years of motor onset

• atrophy on MRI of putamen, middle cerebellar peduncle, pons, or cerebellum

• hypometabolism on fluorodeoxyglucose- PET in putamen, brainstem, or cerebellum.6

Diagnosing MSA can be challenging because its features are similar to those of many other disorders. Nonetheless, Gilman et al6 lists specific criteria for probable MSA, including autonomic dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, and either parkinsonism or cerebellar syndrome symptoms. Although a definite MSA diagnosis only can be made by postmortem brain specimen analysis, Osaki et al7 found that a probable MSA diagnosis has a positive predictive value of 92% with a sensitivity of 22% for definite MSA.

Mr. M’s symptoms were consistent with a diagnosis of probable MSA, cerebellar type (Figure).

Psychiatric manifestations of MSA

There are a few case reports of depression identified early in patients who were later given a diagnosis of MSA.8

Depression. In a study by Benrud-Larson et al9 (N = 99), 49% of patients who had MSA reported moderate or severe depression, as indicated by a score of ≥17 on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); 80% reported at least mild depression (BDI ≥10, mean 17.0, standard deviation, 8.7).

In a similar study, by Balas et al,10 depression was reported as a common symptom and was statistically significant in MSA-P patients compared with controls (P = .013).

Anxiety, another symptom that was reported by Mr. M, is another psychiatric manifestation described by Balas et al10 and Chang et al.11 Balas et al10 noted that MSA-C and MSA-P patients had significantly more state anxiety (P = .009 and P = .022, respectively) compared with controls, although Chang et al11 noted higher anxiety scores in MSA-C patients compared with controls and MSA-P patients (P < .01).

Balas et al10 hypothesized that anxiety and depression contribute to cognitive decline; their study showed that MSA-C patients had difficulty learning new verbal information (P < .022) and controlling attention (P < .023). Mr. M exhibited some of these cognitive difficulties in his reports of losing track of conversations, forgetting the topic of a conversation when speaking, trouble focusing, and difficulty concentrating when driving.

Mr. M had depression and anxiety well before onset of autonomic dysfunction (orthostatic hypotension and erectile dysfunction), which eventually led to an MSA diagnosis. Psychiatrists should understand additional manifestations of MSA so that they can use psychiatric symptoms to identify these conditions in their patients. One of the most well-known and early manifestations of MSA is autonomic dysfunction; among men, another early sign is erectile dysfunction.6 Our patient also exhibited other less well-known symptoms linked to MSA and autonomic dysregulation, including RBD and ocular symptoms (iridocyclitis, glaucoma, decreased visual acuity).

Rapid eye-movement behavior disorder. Psychiatrists should consider screening for RBD during assessment of sleep problems. Identifying RBD is important because early studies have shown a strong association between RBD and development of a neurodegenerative disorder. Mr. M’s clinicians did not consider RBD, although his symptoms of sleepwalking and falling asleep while driving suggest a possible diagnosis. Also, considering this diagnosis would aid in diagnosing a synucleinopathy disorder because a higher incidence of RBD was noted in patients who developed synucleinopathy disorders (eg, Parkinson’s disease [PD] and dementia with Lewy bodies [DLB]) compared with patients who developed non-synucleinopathies (eg, frontotemporal dementia, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, mild cognitive impairment, primary progressive aphasia, and posterior cortical atrophy) or tauopathies (eg, Alzheimer’s disease).12

Zanigni et al13 reported similar findings in a later study that classified patients with RBD as having idiopathic RBD (IRBD) or RBD secondary to an underlying neurodegenerative disorder, particularly an α-synucleinopathy: PD, MSA, and DLB. Most IRBD patients developed 1 of the above mentioned neurodegenerative disorders as long as 10 years after a diagnosis of RBD.

In a study by Iranzo et al,14 patients with MSA were noted to have more severe RBD compared with PD patients. Severity is illustrated by greater periodic leg movements during sleep (P = .001), less total sleep time (P = .023), longer sleep onset latency (P = .023), and a higher percentage of REM sleep without atonia (RSWA, P = .001). McCarter et al15 also noted a higher incidence of RSWA in patients with MSA.

Patients with MSA might therefore be more likely to exhibit difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep and as having RSWA years before the MSA diagnosis.

Several psychotropics (eg, first-generation antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines, carbamazepine, topiramate, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can cause adverse ocular effects, such as closed-angle glaucoma in predisposed persons and retinopathy.16 Therefore, it is important for psychiatrists to ask about ocular symptoms because they might be an early sign of autonomic dysfunction.

Posner and Schlossman17 theorized a causal relationship between autonomic dysfunction and ocular diseases after studying a group of patients who had intermittent unilateral attacks of iridocyclitis and glaucoma (now known as Posner-Schlossman syndrome). They hypothesized that a central cause in the hypothalamus, combined with underlying autonomic dysregulation, could cause the intermittent attacks.

Gherghel et al18 noted a significant difference in ocular blood flow and blood pressure in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) compared with controls. Patients with POAG did not show an increase in blood pressure or ocular blood flow when challenged by cold water, which should have increased their sympathetic activity. Gherghel et al18 concluded that this indicated possible systemic autonomic dysfunction in patients with POAG. In a study by Fischer et al,19 MSA patients also were noted to have significant loss of nasal retinal nerve fiber layer thickness vs controls (P < .05), leading to decreased peripheral vision sensitivity.

Bottom Line

Although psychiatric symptoms are not part of the diagnostic criteria for multiple system atrophy (MSA), they may serve as a clue to consider when they occur with other MSA symptoms. Evaluate the importance of psychiatric symptoms in terms of the whole picture of the patient. Although the diagnosis might not alter the patient’s course, it can allow family members to understand the patient’s condition and prepare for complications that will arise.

Related Resources

• The MSA Coalition. www.multiplesystematrophy.org.

• National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Multiple system atrophy fact sheet. www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/msa/detailmsa.htm.

• Wenning GK, Fanciulli A, eds. Multiple system atrophy. Vienna, Austria: Springer-Verlag Wien; 2014.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq Paroxetine • Paxil

Donepezil • Aricept Travoprost • Travatan

Escitalopram • Lexapro Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Fludrocortisone • Florinef Topiramate • Topamax

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Light-headed

Mr. M, age 73, is a retired project manager who feels light-headed while walking his dog, causing him to go to the emergency department. His history is significant for hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), 3-vessel coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), hyperlipidemia, erectile dysfunction, open-angle glaucoma, hemiretinal vein occlusion, symptoms suggesting rapid eye-movement behavior disorder (RBD), and major depressive disorder (MDD).

The psychiatry consultation-liaison service is asked to help manage Mr. M’s psychiatric medications in the context of orthostatic hypotension and cognitive deficits.

What could be causing Mr. M’s symptoms?

a) drug adverse effect

b) progressive cardiovascular disease

c) MDD

d) all of the above

HISTORY Depression, heart disease

15 years ago. Mr. M experienced his first major depressive episode. His primary care physician (PCP) commented on a history of falling asleep while driving and 1 episode of sleepwalking. His depression was treated to remission with fluoxetine and methylphenidate (dosages were not recorded), the latter also addressed his falling asleep while driving.

5 years ago. Mr. M had another depressive episode characterized by anxiety, difficulty sleeping, and irritability. He also described chest pain; a cardiac work-up revealed extensive CAD, which led to 3-vessel CABG later that year. He also reported dizziness upon standing, which was treated with compression stockings and an increase in sodium intake.

Mr. M continued to express feelings of depression. His cardiologist started him on paroxetine, 10 mg/d, which he took for 2 months and decided to stop because he felt better. He declined psychiatric referral.

4 years ago. Mr. M’s PCP referred him to a psychiatrist for depressed mood, anhedonia, decreased appetite, decreased energy, and difficulty concentrating. Immediate and delayed recall were found to be intact. The psychiatrist diagnosed MDD and Mr. M started escitalopram, 5 mg/d, titrated to 15 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d.

After starting treatment, Mr. M reported decreased libido. Sustained-release bupropion, 150 mg/d, was added to boost the effects of escitalopram and counteract sexual side effects.

At follow-up, Mr. M reported that his depressive symptoms and libido had improved, but that he had been experiencing unsteady gait when getting out of his car, which he had been noticing “for a while”—before he began trazodone. Mr. M was referred to his PCP, who attributed his symptoms to orthostasis. No treatment was indicated at the time because Mr. M’s lightheadedness had resolved.

3 years ago. Mr. M reported a syncopal attack and continued “dizziness.” His PCP prescribed fludrocortisone, 0.1 mg/d, later to be dosed 0.2 mg/d, and symptoms improved.

Although Mr. M had a history of orthostatic hypotension, he was later noted to have supine hypertension. Mr. M’s PCP was concerned that fludrocortisone could be causing the supine hypertension but that decreasing the dosage would cause his orthostatic hypotension to return.

The PCP also was concerned that the psychiatric medications (escitalopram, trazodone, and bupropion) could be causing orthostasis. There was discussion among Mr. M, his PCP, and his psychiatrist of stopping the psychotropics to see if the symptoms would remit; however, because of concerns about Mr. M’s depression, the medications were continued. Mr. M monitored his blood pressure at home and was referred to a neurologist for work-up of potential autonomic dysfunction.

Shortly afterward, Mr. M reported intermittent difficulty keeping track of his thoughts and finishing sentences. His psychiatrist ordered an MRI, which showed chronic small vessel ischemic changes, and started him on donepezil, 5 mg/d.

Neuropsychological testing revealed decreased processing speed and poor recognition memory; otherwise, results showed above-average intellectual ability and average or above-average performance in measures of language, attention, visuospatial/constructional functions, and executive functions—a pattern typically attributable to psychogenic factors, such as depression.

Mr. M reported to his neurologist that he forgets directions while driving but can focus better if he makes a conscious effort. Physical exam was significant hypotension; flat affect; deficits in concentration and short-term recall; mild impairment of Luria motor sequence (composed of a go/no-go and a reciprocal motor task); and vertical and horizontal saccades.1

Mr. M consulted with an ophthalmologist for anterior iridocyclitis and ocular hypertension, which was controlled with travoprost. He continued to experience trouble with his vision and was given a diagnosis of right inferior hemiretinal vein occlusion, macular edema, and suspected glaucoma. Subsequent notes recorded a history of Posner-Schlossman syndrome (a disease characterized by recurrent attacks of increased intraocular pressure in 1 eye with concomitant anterior chamber inflammation). His vision deteriorated until he was diagnosed with ocular hypertension, open-angle glaucoma, and dermatochalasis.

The authors’ observations

Involvement of multiple specialties in a patient’s care brings to question one’s philosophy on medical diagnosis. Interdisciplinary communication would seem to promote the principle of diagnostic parsimony, or Occam’s razor, which suggests a unifying diagnosis to explain all of the patient’s symptoms. Lack of communication might favor Hickam’s dictum, which states that “patients can have as many diseases as they damn well please.”

HISTORY Low energy, forgetfulness

2 years ago. Mr. M noticed low energy and motivation. He continued to work full-time but thought that it was taking him longer to get work done. He was tapered off escitalopram and started on desvenlafaxine, 50 mg/d; donepezil was increased to 10 mg/d.

The syncopal episodes resolved but blood pressure measured at home averaged 150/70 mm Hg. Mr. M was advised to decrease fludrocortisone from 0.2 mg/d to 0.1 mg/d. He tolerated the change and blood pressure measured at home dropped on average to 120 to 130/70 mm Hg.

1 year ago. Mr. M reported that his memory loss had become worse. He perceived having more stress because of forgetfulness and visual difficulties, which had led him to stop driving at night.

At a follow-up appointment with his psychiatrist, Mr. M reported that, first, he had not tapered escitalopram as discussed and, second, he forgot to increase the dosage of desvenlafaxine. A home blood pressure log revealed consistent hypotension; the psychiatrist was concerned that hypotension could be the cause of concentration difficulties and malaise. The psychiatrist advised Mr. M to follow-up with his PCP and neurologist.

Current admission. Shortly after the visit to the psychiatrist, Mr. M presented to the emergency department for increased syncopal events. Work-up was negative for a cardiac cause. A cosyntropin stimulation test was negative, showing that adrenal insufficiency did not cause his orthostatic hypotension. Chart review showed he had been having blood pressure problems for many years, independent of antidepressants. Physical exam revealed lower extremity ataxia and a bilateral extensor plantar reflex.

What diagnosis explains Mr. M’s symptoms?

a) Parkinson’s disease

b) multiple system atrophy (MSA)

c) depression due to a general medical condition

d) dementia

The authors’ observations

MSA, previously referred to as Shy-Drager syndrome, is a rare, rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disorder with an estimated prevalence of 3.7 cases for every 100,000 people worldwide.2 MSA primarily affects middle-aged patients; because it has no cure, most patients die in 7 to 10 years.3

MSA has 2 clinical variants4,5:

• parkinsonian type (MSA-P), characterized by striatonigral degeneration and increased spasticity

• cerebellar type (MSA-C), characterized by more autonomic dysfunction.

MSA has a range of symptoms, making it a challenging diagnosis (Table).6 Although psychiatric symptoms are not part of the diagnostic criteria, they can aid in its diagnosis. In Mr. M’s case, depression, anxiety, orthostatic hypotension, and ataxia support a diagnosis of MSA.

Gilman et al6 delineated 3 diagnostic categories for MSA: definite MSA, probable MSA, and possible MSA. Clinical criteria shared by the 3 diagnostic categories are sporadic and progressive onset after age 30.

Definite MSA requires “neuropathological findings of widespread and abundant CNS alpha-synuclein-positive glial cytoplasmic inclusions,” along with “neurodegenerative changes in striatonigral or olivopontocerebellar structures” at autopsy.6

Probable MSA. Without autopsy findings required for definite MSA, the next most specific diagnostic category is probable MSA. Probable MSA also specifies that the patient show either autonomic failure involving urinary incontinence—this includes erectile dysfunction in men—or, if autonomic failure is absent, orthostatic hypotension within 3 minutes of standing by at least 30 mm Hg systolic pressure or 15 mm Hg diastolic pressure.

Possible MSA has less stringent criteria for orthostatic hypotension. The category includes patients who have only 1 symptom that suggests autonomic failure. Criteria for possible MSA include parkinsonism or a cerebellar syndrome in addition to symptoms of MSA listed in the Table, whereas probable MSA has specific criteria of either a poorly levodopa-responsive parkinsonism (MSA-P) or a cerebellar syndrome (MSA-C). In addition to having parkinsonism or a cerebellar syndrome, and 1 sign of autonomic failure or orthostatic hypotension, patients also must have ≥1 additional feature to be assigned a diagnosis of possible MSA, including:

• rapidly progressive parkinsonism

• poor response to levodopa

• postural instability within 3 years of motor onset

• gait ataxia, cerebellar dysarthria, limb ataxia, or cerebellar oculomotor dysfunction

• dysphagia within 5 years of motor onset

• atrophy on MRI of putamen, middle cerebellar peduncle, pons, or cerebellum

• hypometabolism on fluorodeoxyglucose- PET in putamen, brainstem, or cerebellum.6

Diagnosing MSA can be challenging because its features are similar to those of many other disorders. Nonetheless, Gilman et al6 lists specific criteria for probable MSA, including autonomic dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, and either parkinsonism or cerebellar syndrome symptoms. Although a definite MSA diagnosis only can be made by postmortem brain specimen analysis, Osaki et al7 found that a probable MSA diagnosis has a positive predictive value of 92% with a sensitivity of 22% for definite MSA.

Mr. M’s symptoms were consistent with a diagnosis of probable MSA, cerebellar type (Figure).

Psychiatric manifestations of MSA

There are a few case reports of depression identified early in patients who were later given a diagnosis of MSA.8

Depression. In a study by Benrud-Larson et al9 (N = 99), 49% of patients who had MSA reported moderate or severe depression, as indicated by a score of ≥17 on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); 80% reported at least mild depression (BDI ≥10, mean 17.0, standard deviation, 8.7).

In a similar study, by Balas et al,10 depression was reported as a common symptom and was statistically significant in MSA-P patients compared with controls (P = .013).

Anxiety, another symptom that was reported by Mr. M, is another psychiatric manifestation described by Balas et al10 and Chang et al.11 Balas et al10 noted that MSA-C and MSA-P patients had significantly more state anxiety (P = .009 and P = .022, respectively) compared with controls, although Chang et al11 noted higher anxiety scores in MSA-C patients compared with controls and MSA-P patients (P < .01).

Balas et al10 hypothesized that anxiety and depression contribute to cognitive decline; their study showed that MSA-C patients had difficulty learning new verbal information (P < .022) and controlling attention (P < .023). Mr. M exhibited some of these cognitive difficulties in his reports of losing track of conversations, forgetting the topic of a conversation when speaking, trouble focusing, and difficulty concentrating when driving.

Mr. M had depression and anxiety well before onset of autonomic dysfunction (orthostatic hypotension and erectile dysfunction), which eventually led to an MSA diagnosis. Psychiatrists should understand additional manifestations of MSA so that they can use psychiatric symptoms to identify these conditions in their patients. One of the most well-known and early manifestations of MSA is autonomic dysfunction; among men, another early sign is erectile dysfunction.6 Our patient also exhibited other less well-known symptoms linked to MSA and autonomic dysregulation, including RBD and ocular symptoms (iridocyclitis, glaucoma, decreased visual acuity).

Rapid eye-movement behavior disorder. Psychiatrists should consider screening for RBD during assessment of sleep problems. Identifying RBD is important because early studies have shown a strong association between RBD and development of a neurodegenerative disorder. Mr. M’s clinicians did not consider RBD, although his symptoms of sleepwalking and falling asleep while driving suggest a possible diagnosis. Also, considering this diagnosis would aid in diagnosing a synucleinopathy disorder because a higher incidence of RBD was noted in patients who developed synucleinopathy disorders (eg, Parkinson’s disease [PD] and dementia with Lewy bodies [DLB]) compared with patients who developed non-synucleinopathies (eg, frontotemporal dementia, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, mild cognitive impairment, primary progressive aphasia, and posterior cortical atrophy) or tauopathies (eg, Alzheimer’s disease).12

Zanigni et al13 reported similar findings in a later study that classified patients with RBD as having idiopathic RBD (IRBD) or RBD secondary to an underlying neurodegenerative disorder, particularly an α-synucleinopathy: PD, MSA, and DLB. Most IRBD patients developed 1 of the above mentioned neurodegenerative disorders as long as 10 years after a diagnosis of RBD.

In a study by Iranzo et al,14 patients with MSA were noted to have more severe RBD compared with PD patients. Severity is illustrated by greater periodic leg movements during sleep (P = .001), less total sleep time (P = .023), longer sleep onset latency (P = .023), and a higher percentage of REM sleep without atonia (RSWA, P = .001). McCarter et al15 also noted a higher incidence of RSWA in patients with MSA.

Patients with MSA might therefore be more likely to exhibit difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep and as having RSWA years before the MSA diagnosis.

Several psychotropics (eg, first-generation antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines, carbamazepine, topiramate, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can cause adverse ocular effects, such as closed-angle glaucoma in predisposed persons and retinopathy.16 Therefore, it is important for psychiatrists to ask about ocular symptoms because they might be an early sign of autonomic dysfunction.

Posner and Schlossman17 theorized a causal relationship between autonomic dysfunction and ocular diseases after studying a group of patients who had intermittent unilateral attacks of iridocyclitis and glaucoma (now known as Posner-Schlossman syndrome). They hypothesized that a central cause in the hypothalamus, combined with underlying autonomic dysregulation, could cause the intermittent attacks.

Gherghel et al18 noted a significant difference in ocular blood flow and blood pressure in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) compared with controls. Patients with POAG did not show an increase in blood pressure or ocular blood flow when challenged by cold water, which should have increased their sympathetic activity. Gherghel et al18 concluded that this indicated possible systemic autonomic dysfunction in patients with POAG. In a study by Fischer et al,19 MSA patients also were noted to have significant loss of nasal retinal nerve fiber layer thickness vs controls (P < .05), leading to decreased peripheral vision sensitivity.

Bottom Line

Although psychiatric symptoms are not part of the diagnostic criteria for multiple system atrophy (MSA), they may serve as a clue to consider when they occur with other MSA symptoms. Evaluate the importance of psychiatric symptoms in terms of the whole picture of the patient. Although the diagnosis might not alter the patient’s course, it can allow family members to understand the patient’s condition and prepare for complications that will arise.

Related Resources

• The MSA Coalition. www.multiplesystematrophy.org.

• National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Multiple system atrophy fact sheet. www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/msa/detailmsa.htm.

• Wenning GK, Fanciulli A, eds. Multiple system atrophy. Vienna, Austria: Springer-Verlag Wien; 2014.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq Paroxetine • Paxil

Donepezil • Aricept Travoprost • Travatan

Escitalopram • Lexapro Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Fludrocortisone • Florinef Topiramate • Topamax

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Weiner MF, Hynan LS, Rossetti H, et al. Luria’s three-step test: what is it and what does it tell us? Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(10):1602-1606.

2. Orphanet Report Series. Prevalence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/ cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_ alphabetical_list.pdf. Published May 2014. Accessed May 27, 2015.

3. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Multiple system atrophy with orthostatic hypotension information page. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/ msa_orthostatic_hypotension/msa_orthostatic_ hypotension.htm?css=print. Updated December 5, 2013. Accessed May 27, 2015.

4. Flaherty AW, Rost NS. The Massachusetts Hospital handbook of neurology. 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Boston, MA; 2007:79.

5. Hemingway J, Franco K, Chmelik E. Shy-Drager syndrome: multisystem atrophy with comorbid depression. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(1):73-76.

6. Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008;71(9):670-676.

7. Osaki Y, Wenning GK, Daniel SE, et al. Do published criteria improve clinical diagnostic accuracy in multiple system atrophy? Neurology. 2002;59(10):1486-1491.

8. Goto K, Ueki A, Shimode H, et al. Depression in multiple system atrophy: a case report. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54(4):507-511.

9. Benrud-Larson LM, Sandroni P, Schrag A, et al. Depressive symptoms and life satisfaction in patients with multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord. 2005;20(8):951-957.

10. Balas M, Balash Y, Giladi N, et al. Cognition in multiple system atrophy: neuropsychological profile and interaction with mood. J Neural Transm. 2010;117(3):369-375.

11. Chang CC, Chang YY, Chang WN, et al. Cognitive deficits in multiple system atrophy correlate with frontal atrophy and disease duration. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(10):1144-1150.

12. Boeve BF, Silber MH, Parisi JE, et al. Synucleinopathy pathology and REM sleep behavior disorder plus dementia or parkinsonism. Neurology. 2003;61(1):40-45.

13. Zanigni S, Calandra-Buonaura G, Grimaldi D, et al. REM behaviour disorder and neurodegenerative diseases. Sleep Med. 2011;12(suppl 2):S54-S58.

14. Iranzo A, Santamaria J, Rye DB, et al. Characteristics of idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder and that associated with MSA and PD. Neurology. 2005;65(2):247-252.

15. McCarter SJ, St. Louis EK, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia as early manifestation of degenerative neurological disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12(2):182-192.

16. Richa S, Yazbek JC. Ocular adverse effects of common psychotropic agents: a review. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(6):501-526.

17. Posner A, Schlossman A. Syndrome of unilateral recurrent attacks of glaucoma with cyclitic symptoms. Arch Ophthal. 1948;39(4):517-535.

18. Gherghel D, Hosking SL, Cunliffe IA. Abnormal systemic and ocular vascular response to temperature provocation in primary open-angle glaucoma patients: a case for autonomic failure? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(10):3546-3554.

19. Fischer MD, Synofzik M, Kernstock C, et al. Decreased retinal sensitivity and loss of retinal nerve fibers in multiple system atrophy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Opthalmol. 2013;251(1):235-241.

1. Weiner MF, Hynan LS, Rossetti H, et al. Luria’s three-step test: what is it and what does it tell us? Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(10):1602-1606.

2. Orphanet Report Series. Prevalence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/ cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_ alphabetical_list.pdf. Published May 2014. Accessed May 27, 2015.

3. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Multiple system atrophy with orthostatic hypotension information page. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/ msa_orthostatic_hypotension/msa_orthostatic_ hypotension.htm?css=print. Updated December 5, 2013. Accessed May 27, 2015.

4. Flaherty AW, Rost NS. The Massachusetts Hospital handbook of neurology. 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Boston, MA; 2007:79.

5. Hemingway J, Franco K, Chmelik E. Shy-Drager syndrome: multisystem atrophy with comorbid depression. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(1):73-76.

6. Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008;71(9):670-676.

7. Osaki Y, Wenning GK, Daniel SE, et al. Do published criteria improve clinical diagnostic accuracy in multiple system atrophy? Neurology. 2002;59(10):1486-1491.

8. Goto K, Ueki A, Shimode H, et al. Depression in multiple system atrophy: a case report. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54(4):507-511.

9. Benrud-Larson LM, Sandroni P, Schrag A, et al. Depressive symptoms and life satisfaction in patients with multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord. 2005;20(8):951-957.

10. Balas M, Balash Y, Giladi N, et al. Cognition in multiple system atrophy: neuropsychological profile and interaction with mood. J Neural Transm. 2010;117(3):369-375.

11. Chang CC, Chang YY, Chang WN, et al. Cognitive deficits in multiple system atrophy correlate with frontal atrophy and disease duration. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(10):1144-1150.

12. Boeve BF, Silber MH, Parisi JE, et al. Synucleinopathy pathology and REM sleep behavior disorder plus dementia or parkinsonism. Neurology. 2003;61(1):40-45.

13. Zanigni S, Calandra-Buonaura G, Grimaldi D, et al. REM behaviour disorder and neurodegenerative diseases. Sleep Med. 2011;12(suppl 2):S54-S58.

14. Iranzo A, Santamaria J, Rye DB, et al. Characteristics of idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder and that associated with MSA and PD. Neurology. 2005;65(2):247-252.

15. McCarter SJ, St. Louis EK, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia as early manifestation of degenerative neurological disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12(2):182-192.

16. Richa S, Yazbek JC. Ocular adverse effects of common psychotropic agents: a review. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(6):501-526.

17. Posner A, Schlossman A. Syndrome of unilateral recurrent attacks of glaucoma with cyclitic symptoms. Arch Ophthal. 1948;39(4):517-535.

18. Gherghel D, Hosking SL, Cunliffe IA. Abnormal systemic and ocular vascular response to temperature provocation in primary open-angle glaucoma patients: a case for autonomic failure? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(10):3546-3554.

19. Fischer MD, Synofzik M, Kernstock C, et al. Decreased retinal sensitivity and loss of retinal nerve fibers in multiple system atrophy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Opthalmol. 2013;251(1):235-241.