User login

There is no doubt that nurse practitioners and physician assistants are in demand in the US workforce. A 2013 survey of more than 300 large multispecialty health care organizations indicated that about two-thirds of them had increased their NP/PA workforce and were projecting additional hiring in the next 12 months. Also of note: 31% of these organizations reported having an NP/PA in an administrative role (an increase from 20% in 2012).1

But along with being in demand, our jobs have become increasingly demanding. Health care is changing, not least because of a shortage of primary care physicians, baby boomers increasing their consumption of health care, an increase in chronic disease care, and the growing complexity of health care management. Historically, large studies by our national professional organizations have indicated that NPs and PAs are predominantly satisfied with their role and their future professional prospects. But is that still the case today?

With that question in mind, a quasi-scientific nationwide survey was conducted at the behest of NP Editor-in-Chief Marie-Eileen Onieal and myself. We wanted to determine whether PAs and NPs are satisfied with their work and the state of their profession. This survey, fielded over a two-week period in February, involved a self-selected sample derived from an invitation to almost 100,000 PAs and NPs via the Clinician Reviews mailing list, as well as a posting on the Web site. It should be noted here, for my statistician friends, that this sample may not be representative of the population—but it does create the opportunity for discussion. People who respond to these types of surveys tend to feel strongly, one way or another, about the issues; this questionnaire was no exception.

A total of 240 clinicians participated: 145 NPs (60%) and 95 PAs (40%). The majority (88% of NPs and 86% of PAs) reported being in clinical practice, and 29% of NP respondents and 45% of PA respondents indicated that they have been in their profession for more than 20 years.

Demographically, more women than men participated (NPs, 94%; PAs, 58%), 71% of respondents were between ages 50 and 69, and almost 90% were white. The last item begs the question of the professional satisfaction of nonwhite NPs and PAs. As in other medical fields, the NP and PA professions do not currently emulate the diversity of the US population—which is something we should strive for (perhaps a topic for a future editorial).

Most respondents had “very positive” feelings about their profession (NPs, 73%; PAs, 65%), and many reported feeling “somewhat positive” (NPs, 23%; PAs, 28%). Only 4% of NPs and 7% of PAs expressed negative feelings about the current state of their profession. Perhaps not surprisingly, the majority of both NPs (58%) and PAs (65%) also indicated feeling “very positive” about the future of their profession. Overall, 66% of NPs and 60% of PAs said they would choose the same profession if they had the opportunity again.

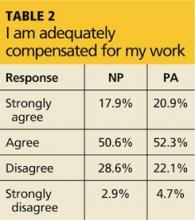

So what, if any, are the drawbacks to being a PA or NP? Well, with regard to workload, participants most commonly endorsed the response that they were working at full capacity but not overextended or overworked (NPs, 43%; PAs, 51%), and the majority felt they were adequately compensated for their work (NPs, 69%; PAs, 73%). However, a significant portion of the remaining respondents had less positive feelings on both subjects; Table 1 and Table 2 provide full data.

Continued on next page >>

The fact that almost one-third of NPs and one-fourth of PAs feel they are overextended and overworked is not lost here. This information is interesting in light of the projection that the workloads of NPs and PAs will increase with the introduction and expansion of team-based health care and with the implementation in primary care of the “medical home” practice model.

Participants were invited to append comments to their responses; these, while of course anecdotal, were rather illuminating of the mindset “in the trenches.” Many clinicians commented on the satisfaction they achieve from providing care and education to patients, their independence as practitioners, and the intellectual and instinctual challenges of diagnosis.

However, several voiced the opinion that NP and PA education programs are no longer as “competitive” as they used to be, noting that the expansion of such programs has led to a perceived attitude of “If you have the dough, you can go.” (As the dean of a PA program, I am of course concerned by this perspective.) This view of the educational system was also reflected in the response to a question about pursuit of a clinical doctorate, with 67% of NPs and 86% of PAs indicating they felt it would not enhance their ability to practice. (On the other hand, one wonders if this is because the majority of respondents are older and have been in the profession longer.)

A similar study by Jackson Healthcare (2012-2013) also noted high levels of job satisfaction among NPs and PAs, with only 5% reporting that they were “very dissatisfied.” In that survey, the five top drivers of NP/PA satisfaction included work environment (37%), patients (28%), compensation (27%), autonomy (21%), and growth opportunities (14%).2

In the same study, NPs and PAs were asked about negative aspects of their jobs. Respondents voiced concern over patient confusion with the NP/PA role, increased administrative duties, and problems with electronic medical records. A significant number mentioned a lack of understanding by physicians and others about the role PAs and NPs play in health care.2

The Jackson study corroborates our findings that overall, NPs and PAs are satisfied with our role and the future of our professions. Our professions continue to be critically important in responding to the converging trends in health care, so it is heartening to see that they continue to offer attractive, fulfilling opportunities to serve tomorrow’s health care needs. At the same time, it is evident that there are some areas with room for improvement. What are your thoughts (good and bad)?

Email me at PAEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. American Medical Group Association. Survey Reveals Advanced Practice Clinician Workforce Continues to Grow and Incentive Pay Is an Increasing Part of the Compensation Mix [press release]. February 12, 2014. www.amga.org/AboutAMGA/News/article_news.asp?k=727. Accessed February 28, 2014.

2. Jackson Healthcare. Advanced Practice Trends 2012-2013: An Attitude & Outlook on Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants. www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/182734/advancedpracticetrendsreport_ebook0313_lr.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2014.

There is no doubt that nurse practitioners and physician assistants are in demand in the US workforce. A 2013 survey of more than 300 large multispecialty health care organizations indicated that about two-thirds of them had increased their NP/PA workforce and were projecting additional hiring in the next 12 months. Also of note: 31% of these organizations reported having an NP/PA in an administrative role (an increase from 20% in 2012).1

But along with being in demand, our jobs have become increasingly demanding. Health care is changing, not least because of a shortage of primary care physicians, baby boomers increasing their consumption of health care, an increase in chronic disease care, and the growing complexity of health care management. Historically, large studies by our national professional organizations have indicated that NPs and PAs are predominantly satisfied with their role and their future professional prospects. But is that still the case today?

With that question in mind, a quasi-scientific nationwide survey was conducted at the behest of NP Editor-in-Chief Marie-Eileen Onieal and myself. We wanted to determine whether PAs and NPs are satisfied with their work and the state of their profession. This survey, fielded over a two-week period in February, involved a self-selected sample derived from an invitation to almost 100,000 PAs and NPs via the Clinician Reviews mailing list, as well as a posting on the Web site. It should be noted here, for my statistician friends, that this sample may not be representative of the population—but it does create the opportunity for discussion. People who respond to these types of surveys tend to feel strongly, one way or another, about the issues; this questionnaire was no exception.

A total of 240 clinicians participated: 145 NPs (60%) and 95 PAs (40%). The majority (88% of NPs and 86% of PAs) reported being in clinical practice, and 29% of NP respondents and 45% of PA respondents indicated that they have been in their profession for more than 20 years.

Demographically, more women than men participated (NPs, 94%; PAs, 58%), 71% of respondents were between ages 50 and 69, and almost 90% were white. The last item begs the question of the professional satisfaction of nonwhite NPs and PAs. As in other medical fields, the NP and PA professions do not currently emulate the diversity of the US population—which is something we should strive for (perhaps a topic for a future editorial).

Most respondents had “very positive” feelings about their profession (NPs, 73%; PAs, 65%), and many reported feeling “somewhat positive” (NPs, 23%; PAs, 28%). Only 4% of NPs and 7% of PAs expressed negative feelings about the current state of their profession. Perhaps not surprisingly, the majority of both NPs (58%) and PAs (65%) also indicated feeling “very positive” about the future of their profession. Overall, 66% of NPs and 60% of PAs said they would choose the same profession if they had the opportunity again.

So what, if any, are the drawbacks to being a PA or NP? Well, with regard to workload, participants most commonly endorsed the response that they were working at full capacity but not overextended or overworked (NPs, 43%; PAs, 51%), and the majority felt they were adequately compensated for their work (NPs, 69%; PAs, 73%). However, a significant portion of the remaining respondents had less positive feelings on both subjects; Table 1 and Table 2 provide full data.

Continued on next page >>

The fact that almost one-third of NPs and one-fourth of PAs feel they are overextended and overworked is not lost here. This information is interesting in light of the projection that the workloads of NPs and PAs will increase with the introduction and expansion of team-based health care and with the implementation in primary care of the “medical home” practice model.

Participants were invited to append comments to their responses; these, while of course anecdotal, were rather illuminating of the mindset “in the trenches.” Many clinicians commented on the satisfaction they achieve from providing care and education to patients, their independence as practitioners, and the intellectual and instinctual challenges of diagnosis.

However, several voiced the opinion that NP and PA education programs are no longer as “competitive” as they used to be, noting that the expansion of such programs has led to a perceived attitude of “If you have the dough, you can go.” (As the dean of a PA program, I am of course concerned by this perspective.) This view of the educational system was also reflected in the response to a question about pursuit of a clinical doctorate, with 67% of NPs and 86% of PAs indicating they felt it would not enhance their ability to practice. (On the other hand, one wonders if this is because the majority of respondents are older and have been in the profession longer.)

A similar study by Jackson Healthcare (2012-2013) also noted high levels of job satisfaction among NPs and PAs, with only 5% reporting that they were “very dissatisfied.” In that survey, the five top drivers of NP/PA satisfaction included work environment (37%), patients (28%), compensation (27%), autonomy (21%), and growth opportunities (14%).2

In the same study, NPs and PAs were asked about negative aspects of their jobs. Respondents voiced concern over patient confusion with the NP/PA role, increased administrative duties, and problems with electronic medical records. A significant number mentioned a lack of understanding by physicians and others about the role PAs and NPs play in health care.2

The Jackson study corroborates our findings that overall, NPs and PAs are satisfied with our role and the future of our professions. Our professions continue to be critically important in responding to the converging trends in health care, so it is heartening to see that they continue to offer attractive, fulfilling opportunities to serve tomorrow’s health care needs. At the same time, it is evident that there are some areas with room for improvement. What are your thoughts (good and bad)?

Email me at PAEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. American Medical Group Association. Survey Reveals Advanced Practice Clinician Workforce Continues to Grow and Incentive Pay Is an Increasing Part of the Compensation Mix [press release]. February 12, 2014. www.amga.org/AboutAMGA/News/article_news.asp?k=727. Accessed February 28, 2014.

2. Jackson Healthcare. Advanced Practice Trends 2012-2013: An Attitude & Outlook on Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants. www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/182734/advancedpracticetrendsreport_ebook0313_lr.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2014.

There is no doubt that nurse practitioners and physician assistants are in demand in the US workforce. A 2013 survey of more than 300 large multispecialty health care organizations indicated that about two-thirds of them had increased their NP/PA workforce and were projecting additional hiring in the next 12 months. Also of note: 31% of these organizations reported having an NP/PA in an administrative role (an increase from 20% in 2012).1

But along with being in demand, our jobs have become increasingly demanding. Health care is changing, not least because of a shortage of primary care physicians, baby boomers increasing their consumption of health care, an increase in chronic disease care, and the growing complexity of health care management. Historically, large studies by our national professional organizations have indicated that NPs and PAs are predominantly satisfied with their role and their future professional prospects. But is that still the case today?

With that question in mind, a quasi-scientific nationwide survey was conducted at the behest of NP Editor-in-Chief Marie-Eileen Onieal and myself. We wanted to determine whether PAs and NPs are satisfied with their work and the state of their profession. This survey, fielded over a two-week period in February, involved a self-selected sample derived from an invitation to almost 100,000 PAs and NPs via the Clinician Reviews mailing list, as well as a posting on the Web site. It should be noted here, for my statistician friends, that this sample may not be representative of the population—but it does create the opportunity for discussion. People who respond to these types of surveys tend to feel strongly, one way or another, about the issues; this questionnaire was no exception.

A total of 240 clinicians participated: 145 NPs (60%) and 95 PAs (40%). The majority (88% of NPs and 86% of PAs) reported being in clinical practice, and 29% of NP respondents and 45% of PA respondents indicated that they have been in their profession for more than 20 years.

Demographically, more women than men participated (NPs, 94%; PAs, 58%), 71% of respondents were between ages 50 and 69, and almost 90% were white. The last item begs the question of the professional satisfaction of nonwhite NPs and PAs. As in other medical fields, the NP and PA professions do not currently emulate the diversity of the US population—which is something we should strive for (perhaps a topic for a future editorial).

Most respondents had “very positive” feelings about their profession (NPs, 73%; PAs, 65%), and many reported feeling “somewhat positive” (NPs, 23%; PAs, 28%). Only 4% of NPs and 7% of PAs expressed negative feelings about the current state of their profession. Perhaps not surprisingly, the majority of both NPs (58%) and PAs (65%) also indicated feeling “very positive” about the future of their profession. Overall, 66% of NPs and 60% of PAs said they would choose the same profession if they had the opportunity again.

So what, if any, are the drawbacks to being a PA or NP? Well, with regard to workload, participants most commonly endorsed the response that they were working at full capacity but not overextended or overworked (NPs, 43%; PAs, 51%), and the majority felt they were adequately compensated for their work (NPs, 69%; PAs, 73%). However, a significant portion of the remaining respondents had less positive feelings on both subjects; Table 1 and Table 2 provide full data.

Continued on next page >>

The fact that almost one-third of NPs and one-fourth of PAs feel they are overextended and overworked is not lost here. This information is interesting in light of the projection that the workloads of NPs and PAs will increase with the introduction and expansion of team-based health care and with the implementation in primary care of the “medical home” practice model.

Participants were invited to append comments to their responses; these, while of course anecdotal, were rather illuminating of the mindset “in the trenches.” Many clinicians commented on the satisfaction they achieve from providing care and education to patients, their independence as practitioners, and the intellectual and instinctual challenges of diagnosis.

However, several voiced the opinion that NP and PA education programs are no longer as “competitive” as they used to be, noting that the expansion of such programs has led to a perceived attitude of “If you have the dough, you can go.” (As the dean of a PA program, I am of course concerned by this perspective.) This view of the educational system was also reflected in the response to a question about pursuit of a clinical doctorate, with 67% of NPs and 86% of PAs indicating they felt it would not enhance their ability to practice. (On the other hand, one wonders if this is because the majority of respondents are older and have been in the profession longer.)

A similar study by Jackson Healthcare (2012-2013) also noted high levels of job satisfaction among NPs and PAs, with only 5% reporting that they were “very dissatisfied.” In that survey, the five top drivers of NP/PA satisfaction included work environment (37%), patients (28%), compensation (27%), autonomy (21%), and growth opportunities (14%).2

In the same study, NPs and PAs were asked about negative aspects of their jobs. Respondents voiced concern over patient confusion with the NP/PA role, increased administrative duties, and problems with electronic medical records. A significant number mentioned a lack of understanding by physicians and others about the role PAs and NPs play in health care.2

The Jackson study corroborates our findings that overall, NPs and PAs are satisfied with our role and the future of our professions. Our professions continue to be critically important in responding to the converging trends in health care, so it is heartening to see that they continue to offer attractive, fulfilling opportunities to serve tomorrow’s health care needs. At the same time, it is evident that there are some areas with room for improvement. What are your thoughts (good and bad)?

Email me at PAEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. American Medical Group Association. Survey Reveals Advanced Practice Clinician Workforce Continues to Grow and Incentive Pay Is an Increasing Part of the Compensation Mix [press release]. February 12, 2014. www.amga.org/AboutAMGA/News/article_news.asp?k=727. Accessed February 28, 2014.

2. Jackson Healthcare. Advanced Practice Trends 2012-2013: An Attitude & Outlook on Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants. www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/182734/advancedpracticetrendsreport_ebook0313_lr.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2014.