User login

As hospitalists, we focus on financial metrics such as length of stay, readmissions, and discharge time to evaluate one’s performance. Since professional billing is usually tied to a hospitalist’s salary, we also learn about CPT coding for professional services. While these are clearly important, our documentation likely has a bigger financial impact on a hospital than do any of these metrics. A little understanding of how a hospital is paid could have huge financial implications to you and your hospital.

Medicare pays for inpatient services based on the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) system. Other federal payers, and the majority of commercial payers, also use a variant of this model for payment. In this model, similar diagnosis codes are grouped into a DRG, and each DRG has a corresponding Relative Weight.

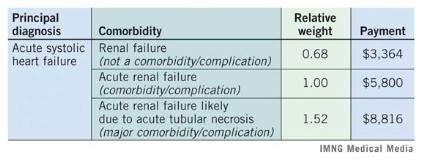

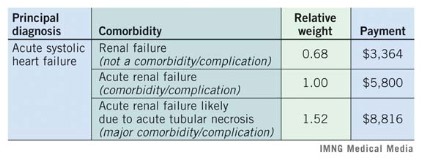

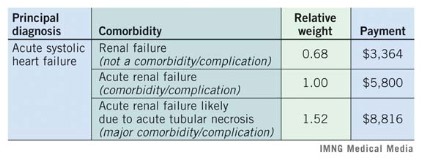

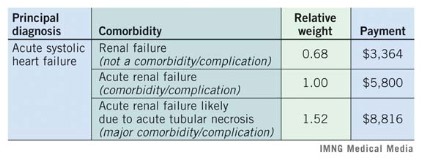

Most important to a hospitalist is how greater documentation specificity changes the DRG to one with a higher weight. Higher weight DRGs reflect sicker patients and also reimburse more. There are two type of comorbidities/complications: minor (CCs) and major (MCCs). Below is an example of how CCs and MCCs affect weight and payment.

Medicare payment follows a basic formula: blended rate x relative weight. A hospital’s blended rate is fixed and is based mostly on factors such as labor costs, inflation, and teaching status. In this example, we used a blended rate of $5,800, which is the average blended rate for hospitals in 2012. In the table above, documenting the likely cause of renal failure more than doubled the hospital reimbursement of the patient with heart failure. Importantly, coders can only code from a provider’s documentation, so if we don’t document the specifics, the coders cannot code it. These same principles hold true to arrive at a case-mix-index (CMI) of your patients – a higher CMI reflects sicker patients and affects publicly reported severity-adjusted outcomes.

There are more than 3,000 minor CCs and 1,400 major MCCs in the code book, but paying attention and documenting a few common conditions will make a huge difference.

Consider this top 10 list for ways to improve your documentation and see what it does to your CMI. Because hospital reimbursement will also increase, you will gain negotiating power with your hospital administrators.

Ten common underdocumented comorbidities

• SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome)/sepsis

• Shock (e.g. septic, cardiogenic, etc).

• Encephalopathy

• AIDS

• Obesity

• Acute renal failure likely caused by [specific condition]

• Anemia/pancytopenia from chemotherapy

• Chronic respiratory failure

• Severe malnutrition

• Heart failure

a. acute vs. chronic

b. systolic vs. diastolic

Dr. Pendleton is chief medical quality officer for University of Utah Health Care, Salt Lake City, and a member of the Hospitalist News advisory board. Michelle Knuckles, RHIT, is manager of inpatient doding and documentation improvement for University of Utah Health Care. Dr. Vinik is a hospitalist and director of utilization review for the University of Utah Hospital.

Michelle Knuckles, RHIT , coding,

As hospitalists, we focus on financial metrics such as length of stay, readmissions, and discharge time to evaluate one’s performance. Since professional billing is usually tied to a hospitalist’s salary, we also learn about CPT coding for professional services. While these are clearly important, our documentation likely has a bigger financial impact on a hospital than do any of these metrics. A little understanding of how a hospital is paid could have huge financial implications to you and your hospital.

Medicare pays for inpatient services based on the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) system. Other federal payers, and the majority of commercial payers, also use a variant of this model for payment. In this model, similar diagnosis codes are grouped into a DRG, and each DRG has a corresponding Relative Weight.

Most important to a hospitalist is how greater documentation specificity changes the DRG to one with a higher weight. Higher weight DRGs reflect sicker patients and also reimburse more. There are two type of comorbidities/complications: minor (CCs) and major (MCCs). Below is an example of how CCs and MCCs affect weight and payment.

Medicare payment follows a basic formula: blended rate x relative weight. A hospital’s blended rate is fixed and is based mostly on factors such as labor costs, inflation, and teaching status. In this example, we used a blended rate of $5,800, which is the average blended rate for hospitals in 2012. In the table above, documenting the likely cause of renal failure more than doubled the hospital reimbursement of the patient with heart failure. Importantly, coders can only code from a provider’s documentation, so if we don’t document the specifics, the coders cannot code it. These same principles hold true to arrive at a case-mix-index (CMI) of your patients – a higher CMI reflects sicker patients and affects publicly reported severity-adjusted outcomes.

There are more than 3,000 minor CCs and 1,400 major MCCs in the code book, but paying attention and documenting a few common conditions will make a huge difference.

Consider this top 10 list for ways to improve your documentation and see what it does to your CMI. Because hospital reimbursement will also increase, you will gain negotiating power with your hospital administrators.

Ten common underdocumented comorbidities

• SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome)/sepsis

• Shock (e.g. septic, cardiogenic, etc).

• Encephalopathy

• AIDS

• Obesity

• Acute renal failure likely caused by [specific condition]

• Anemia/pancytopenia from chemotherapy

• Chronic respiratory failure

• Severe malnutrition

• Heart failure

a. acute vs. chronic

b. systolic vs. diastolic

Dr. Pendleton is chief medical quality officer for University of Utah Health Care, Salt Lake City, and a member of the Hospitalist News advisory board. Michelle Knuckles, RHIT, is manager of inpatient doding and documentation improvement for University of Utah Health Care. Dr. Vinik is a hospitalist and director of utilization review for the University of Utah Hospital.

As hospitalists, we focus on financial metrics such as length of stay, readmissions, and discharge time to evaluate one’s performance. Since professional billing is usually tied to a hospitalist’s salary, we also learn about CPT coding for professional services. While these are clearly important, our documentation likely has a bigger financial impact on a hospital than do any of these metrics. A little understanding of how a hospital is paid could have huge financial implications to you and your hospital.

Medicare pays for inpatient services based on the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) system. Other federal payers, and the majority of commercial payers, also use a variant of this model for payment. In this model, similar diagnosis codes are grouped into a DRG, and each DRG has a corresponding Relative Weight.

Most important to a hospitalist is how greater documentation specificity changes the DRG to one with a higher weight. Higher weight DRGs reflect sicker patients and also reimburse more. There are two type of comorbidities/complications: minor (CCs) and major (MCCs). Below is an example of how CCs and MCCs affect weight and payment.

Medicare payment follows a basic formula: blended rate x relative weight. A hospital’s blended rate is fixed and is based mostly on factors such as labor costs, inflation, and teaching status. In this example, we used a blended rate of $5,800, which is the average blended rate for hospitals in 2012. In the table above, documenting the likely cause of renal failure more than doubled the hospital reimbursement of the patient with heart failure. Importantly, coders can only code from a provider’s documentation, so if we don’t document the specifics, the coders cannot code it. These same principles hold true to arrive at a case-mix-index (CMI) of your patients – a higher CMI reflects sicker patients and affects publicly reported severity-adjusted outcomes.

There are more than 3,000 minor CCs and 1,400 major MCCs in the code book, but paying attention and documenting a few common conditions will make a huge difference.

Consider this top 10 list for ways to improve your documentation and see what it does to your CMI. Because hospital reimbursement will also increase, you will gain negotiating power with your hospital administrators.

Ten common underdocumented comorbidities

• SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome)/sepsis

• Shock (e.g. septic, cardiogenic, etc).

• Encephalopathy

• AIDS

• Obesity

• Acute renal failure likely caused by [specific condition]

• Anemia/pancytopenia from chemotherapy

• Chronic respiratory failure

• Severe malnutrition

• Heart failure

a. acute vs. chronic

b. systolic vs. diastolic

Dr. Pendleton is chief medical quality officer for University of Utah Health Care, Salt Lake City, and a member of the Hospitalist News advisory board. Michelle Knuckles, RHIT, is manager of inpatient doding and documentation improvement for University of Utah Health Care. Dr. Vinik is a hospitalist and director of utilization review for the University of Utah Hospital.

Michelle Knuckles, RHIT , coding,

Michelle Knuckles, RHIT , coding,