User login

What do making airbags and delivering health care have in common? (Continuous Improvement, Part 1)

I joined fellow senior leaders from University of Utah Health Care to spend the day at Autoliv in Ogden, Utah, for a field trip. For those unaware, Autoliv is a world leader in saving lives in the automobile industry – 25,000+ lives saved every year via Autoliv’s safety equipment (equipment like airbags and seatbelts), the company says.

This responsibility to their customers (everyday drivers like you and me) is one that Autoliv employees seem to take very seriously and one that focuses them on an amazing culture of continuous improvement. Autoliv fosters this culture via the motto that leaders are teachers who work relentlessly to teach their employees and not judge them, who remove barriers that hinder success in achieving high quality, who reward the front-line reporting of safety hazards (product defects), who promote a data-driven management system, who design the work-space layout to fuel efficiency, and who harness the knowledge and innovative spirit of their workforce to be ever better.

At Autoliv, visual cues are abundant – capitalizing on the fact that people are visual creatures who use visual signals (think traffic lights and fuel indicator gauges) to be efficient and safe in our daily lives. Real-time performance data are everywhere, guiding management response to immediately address safety or efficiency concerns. For example, one can look across the shop floor to see the worker cell with the big red X where there is a problem that management needs to immediately address and one with a yellow triangle where production is slow but the problem is being addressed.

This remarkable management system is called the Autoliv Production System and is Autoliv’s application of Lean principles (Lean is the Americanized version of the Toyota production system), philosophy, and culture. Autoliv is so advanced in its application of Lean that people and companies from around the world come to learn from it.

Effective leadership, customer focus, saving lives, quality, safety, efficiency, mistake proofing – these attributes sound a lot like the necessary goals of our health care system in need. Indeed, there is much for health care to learn (and much to apply!) from companies like Autoliv that have mastered the art of continuous improvement and the relentless pursuit to be ever better. Those who say, "Yes, but they make widgets and we care for people," have not opened their mind up to the possibilities of how to reinvent process-engineering methods –Lean, Six Sigma, PDSA (plan-do-study-act) – into the health care vernacular.

For example, one of our hospitalists has re-engineered how we (all the hospitalists in our group) round with our team to provide consistent and exceptional value to our patients. As part of this process, who is at bedside rounds and each individual’s role in the rounding process are predefined, communication strategies are integrated, and the use of a checklist is religiously followed with the use of a visual reminder and a pocket card. Outcomes are tracked and made transparent, including effectiveness of pain management, unnecessary use of laboratory resources, Foley catheter use and associated infection rates, and medication errors. These data are then assessed by the team monthly with the goal of continuing to improve the process. The results of this process of continuous improvement using Lean principles? Better care at lower costs.

At a system level, early adopters in health care like ThedaCare in Wisconsin and the Virginia Mason Institute in Seattle have done just that. Yet, what was abundantly clear from visiting Autoliv is that, if you take one company’s continuous improvement system and try to apply it to your own, you will fail. Every organization has a unique starting point, unique strengths/weaknesses/opportunities, and a unique culture in which the philosophies, principles, and application of continuous improvement methodology must be reinvented locally – a remarkable opportunity for innovation!

At University of Utah Health Care, we were inspired by Autoliv and energized by the opportunity to reinvent Lean into our own local vernacular and culture. As a U.S. health care system, we need to be committed to this remarkable and necessary journey of ever better and the pursuit of perfection. Our patients deserve this, and the survival of our nation’s health care system depends on it.

As part of the next Systemness blog, I will explore why clinicians must take the lead in continuous improvement and what methods to consider. In the meantime, where are you and your organization in the journey to be ever better?

Dr. Pendleton is chief medical quality officer at University of Utah Health Care in Salt Lake City. He reports having no financial conflicts of interest. Find him on Twitter @MDBobP.

I joined fellow senior leaders from University of Utah Health Care to spend the day at Autoliv in Ogden, Utah, for a field trip. For those unaware, Autoliv is a world leader in saving lives in the automobile industry – 25,000+ lives saved every year via Autoliv’s safety equipment (equipment like airbags and seatbelts), the company says.

This responsibility to their customers (everyday drivers like you and me) is one that Autoliv employees seem to take very seriously and one that focuses them on an amazing culture of continuous improvement. Autoliv fosters this culture via the motto that leaders are teachers who work relentlessly to teach their employees and not judge them, who remove barriers that hinder success in achieving high quality, who reward the front-line reporting of safety hazards (product defects), who promote a data-driven management system, who design the work-space layout to fuel efficiency, and who harness the knowledge and innovative spirit of their workforce to be ever better.

At Autoliv, visual cues are abundant – capitalizing on the fact that people are visual creatures who use visual signals (think traffic lights and fuel indicator gauges) to be efficient and safe in our daily lives. Real-time performance data are everywhere, guiding management response to immediately address safety or efficiency concerns. For example, one can look across the shop floor to see the worker cell with the big red X where there is a problem that management needs to immediately address and one with a yellow triangle where production is slow but the problem is being addressed.

This remarkable management system is called the Autoliv Production System and is Autoliv’s application of Lean principles (Lean is the Americanized version of the Toyota production system), philosophy, and culture. Autoliv is so advanced in its application of Lean that people and companies from around the world come to learn from it.

Effective leadership, customer focus, saving lives, quality, safety, efficiency, mistake proofing – these attributes sound a lot like the necessary goals of our health care system in need. Indeed, there is much for health care to learn (and much to apply!) from companies like Autoliv that have mastered the art of continuous improvement and the relentless pursuit to be ever better. Those who say, "Yes, but they make widgets and we care for people," have not opened their mind up to the possibilities of how to reinvent process-engineering methods –Lean, Six Sigma, PDSA (plan-do-study-act) – into the health care vernacular.

For example, one of our hospitalists has re-engineered how we (all the hospitalists in our group) round with our team to provide consistent and exceptional value to our patients. As part of this process, who is at bedside rounds and each individual’s role in the rounding process are predefined, communication strategies are integrated, and the use of a checklist is religiously followed with the use of a visual reminder and a pocket card. Outcomes are tracked and made transparent, including effectiveness of pain management, unnecessary use of laboratory resources, Foley catheter use and associated infection rates, and medication errors. These data are then assessed by the team monthly with the goal of continuing to improve the process. The results of this process of continuous improvement using Lean principles? Better care at lower costs.

At a system level, early adopters in health care like ThedaCare in Wisconsin and the Virginia Mason Institute in Seattle have done just that. Yet, what was abundantly clear from visiting Autoliv is that, if you take one company’s continuous improvement system and try to apply it to your own, you will fail. Every organization has a unique starting point, unique strengths/weaknesses/opportunities, and a unique culture in which the philosophies, principles, and application of continuous improvement methodology must be reinvented locally – a remarkable opportunity for innovation!

At University of Utah Health Care, we were inspired by Autoliv and energized by the opportunity to reinvent Lean into our own local vernacular and culture. As a U.S. health care system, we need to be committed to this remarkable and necessary journey of ever better and the pursuit of perfection. Our patients deserve this, and the survival of our nation’s health care system depends on it.

As part of the next Systemness blog, I will explore why clinicians must take the lead in continuous improvement and what methods to consider. In the meantime, where are you and your organization in the journey to be ever better?

Dr. Pendleton is chief medical quality officer at University of Utah Health Care in Salt Lake City. He reports having no financial conflicts of interest. Find him on Twitter @MDBobP.

I joined fellow senior leaders from University of Utah Health Care to spend the day at Autoliv in Ogden, Utah, for a field trip. For those unaware, Autoliv is a world leader in saving lives in the automobile industry – 25,000+ lives saved every year via Autoliv’s safety equipment (equipment like airbags and seatbelts), the company says.

This responsibility to their customers (everyday drivers like you and me) is one that Autoliv employees seem to take very seriously and one that focuses them on an amazing culture of continuous improvement. Autoliv fosters this culture via the motto that leaders are teachers who work relentlessly to teach their employees and not judge them, who remove barriers that hinder success in achieving high quality, who reward the front-line reporting of safety hazards (product defects), who promote a data-driven management system, who design the work-space layout to fuel efficiency, and who harness the knowledge and innovative spirit of their workforce to be ever better.

At Autoliv, visual cues are abundant – capitalizing on the fact that people are visual creatures who use visual signals (think traffic lights and fuel indicator gauges) to be efficient and safe in our daily lives. Real-time performance data are everywhere, guiding management response to immediately address safety or efficiency concerns. For example, one can look across the shop floor to see the worker cell with the big red X where there is a problem that management needs to immediately address and one with a yellow triangle where production is slow but the problem is being addressed.

This remarkable management system is called the Autoliv Production System and is Autoliv’s application of Lean principles (Lean is the Americanized version of the Toyota production system), philosophy, and culture. Autoliv is so advanced in its application of Lean that people and companies from around the world come to learn from it.

Effective leadership, customer focus, saving lives, quality, safety, efficiency, mistake proofing – these attributes sound a lot like the necessary goals of our health care system in need. Indeed, there is much for health care to learn (and much to apply!) from companies like Autoliv that have mastered the art of continuous improvement and the relentless pursuit to be ever better. Those who say, "Yes, but they make widgets and we care for people," have not opened their mind up to the possibilities of how to reinvent process-engineering methods –Lean, Six Sigma, PDSA (plan-do-study-act) – into the health care vernacular.

For example, one of our hospitalists has re-engineered how we (all the hospitalists in our group) round with our team to provide consistent and exceptional value to our patients. As part of this process, who is at bedside rounds and each individual’s role in the rounding process are predefined, communication strategies are integrated, and the use of a checklist is religiously followed with the use of a visual reminder and a pocket card. Outcomes are tracked and made transparent, including effectiveness of pain management, unnecessary use of laboratory resources, Foley catheter use and associated infection rates, and medication errors. These data are then assessed by the team monthly with the goal of continuing to improve the process. The results of this process of continuous improvement using Lean principles? Better care at lower costs.

At a system level, early adopters in health care like ThedaCare in Wisconsin and the Virginia Mason Institute in Seattle have done just that. Yet, what was abundantly clear from visiting Autoliv is that, if you take one company’s continuous improvement system and try to apply it to your own, you will fail. Every organization has a unique starting point, unique strengths/weaknesses/opportunities, and a unique culture in which the philosophies, principles, and application of continuous improvement methodology must be reinvented locally – a remarkable opportunity for innovation!

At University of Utah Health Care, we were inspired by Autoliv and energized by the opportunity to reinvent Lean into our own local vernacular and culture. As a U.S. health care system, we need to be committed to this remarkable and necessary journey of ever better and the pursuit of perfection. Our patients deserve this, and the survival of our nation’s health care system depends on it.

As part of the next Systemness blog, I will explore why clinicians must take the lead in continuous improvement and what methods to consider. In the meantime, where are you and your organization in the journey to be ever better?

Dr. Pendleton is chief medical quality officer at University of Utah Health Care in Salt Lake City. He reports having no financial conflicts of interest. Find him on Twitter @MDBobP.

The dollars and sense of coding and documentation

As hospitalists, we focus on financial metrics such as length of stay, readmissions, and discharge time to evaluate one’s performance. Since professional billing is usually tied to a hospitalist’s salary, we also learn about CPT coding for professional services. While these are clearly important, our documentation likely has a bigger financial impact on a hospital than do any of these metrics. A little understanding of how a hospital is paid could have huge financial implications to you and your hospital.

Medicare pays for inpatient services based on the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) system. Other federal payers, and the majority of commercial payers, also use a variant of this model for payment. In this model, similar diagnosis codes are grouped into a DRG, and each DRG has a corresponding Relative Weight.

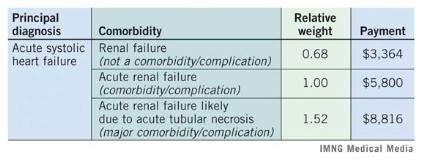

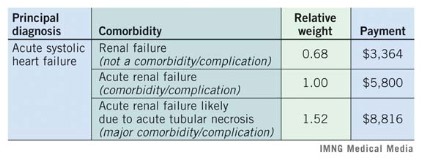

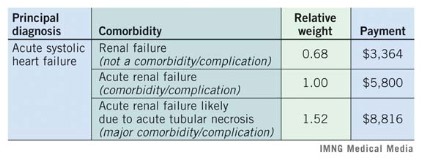

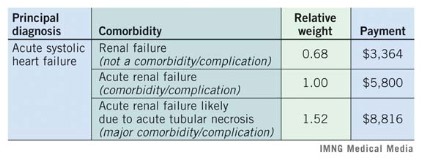

Most important to a hospitalist is how greater documentation specificity changes the DRG to one with a higher weight. Higher weight DRGs reflect sicker patients and also reimburse more. There are two type of comorbidities/complications: minor (CCs) and major (MCCs). Below is an example of how CCs and MCCs affect weight and payment.

Medicare payment follows a basic formula: blended rate x relative weight. A hospital’s blended rate is fixed and is based mostly on factors such as labor costs, inflation, and teaching status. In this example, we used a blended rate of $5,800, which is the average blended rate for hospitals in 2012. In the table above, documenting the likely cause of renal failure more than doubled the hospital reimbursement of the patient with heart failure. Importantly, coders can only code from a provider’s documentation, so if we don’t document the specifics, the coders cannot code it. These same principles hold true to arrive at a case-mix-index (CMI) of your patients – a higher CMI reflects sicker patients and affects publicly reported severity-adjusted outcomes.

There are more than 3,000 minor CCs and 1,400 major MCCs in the code book, but paying attention and documenting a few common conditions will make a huge difference.

Consider this top 10 list for ways to improve your documentation and see what it does to your CMI. Because hospital reimbursement will also increase, you will gain negotiating power with your hospital administrators.

Ten common underdocumented comorbidities

• SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome)/sepsis

• Shock (e.g. septic, cardiogenic, etc).

• Encephalopathy

• AIDS

• Obesity

• Acute renal failure likely caused by [specific condition]

• Anemia/pancytopenia from chemotherapy

• Chronic respiratory failure

• Severe malnutrition

• Heart failure

a. acute vs. chronic

b. systolic vs. diastolic

Dr. Pendleton is chief medical quality officer for University of Utah Health Care, Salt Lake City, and a member of the Hospitalist News advisory board. Michelle Knuckles, RHIT, is manager of inpatient doding and documentation improvement for University of Utah Health Care. Dr. Vinik is a hospitalist and director of utilization review for the University of Utah Hospital.

Michelle Knuckles, RHIT , coding,

As hospitalists, we focus on financial metrics such as length of stay, readmissions, and discharge time to evaluate one’s performance. Since professional billing is usually tied to a hospitalist’s salary, we also learn about CPT coding for professional services. While these are clearly important, our documentation likely has a bigger financial impact on a hospital than do any of these metrics. A little understanding of how a hospital is paid could have huge financial implications to you and your hospital.

Medicare pays for inpatient services based on the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) system. Other federal payers, and the majority of commercial payers, also use a variant of this model for payment. In this model, similar diagnosis codes are grouped into a DRG, and each DRG has a corresponding Relative Weight.

Most important to a hospitalist is how greater documentation specificity changes the DRG to one with a higher weight. Higher weight DRGs reflect sicker patients and also reimburse more. There are two type of comorbidities/complications: minor (CCs) and major (MCCs). Below is an example of how CCs and MCCs affect weight and payment.

Medicare payment follows a basic formula: blended rate x relative weight. A hospital’s blended rate is fixed and is based mostly on factors such as labor costs, inflation, and teaching status. In this example, we used a blended rate of $5,800, which is the average blended rate for hospitals in 2012. In the table above, documenting the likely cause of renal failure more than doubled the hospital reimbursement of the patient with heart failure. Importantly, coders can only code from a provider’s documentation, so if we don’t document the specifics, the coders cannot code it. These same principles hold true to arrive at a case-mix-index (CMI) of your patients – a higher CMI reflects sicker patients and affects publicly reported severity-adjusted outcomes.

There are more than 3,000 minor CCs and 1,400 major MCCs in the code book, but paying attention and documenting a few common conditions will make a huge difference.

Consider this top 10 list for ways to improve your documentation and see what it does to your CMI. Because hospital reimbursement will also increase, you will gain negotiating power with your hospital administrators.

Ten common underdocumented comorbidities

• SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome)/sepsis

• Shock (e.g. septic, cardiogenic, etc).

• Encephalopathy

• AIDS

• Obesity

• Acute renal failure likely caused by [specific condition]

• Anemia/pancytopenia from chemotherapy

• Chronic respiratory failure

• Severe malnutrition

• Heart failure

a. acute vs. chronic

b. systolic vs. diastolic

Dr. Pendleton is chief medical quality officer for University of Utah Health Care, Salt Lake City, and a member of the Hospitalist News advisory board. Michelle Knuckles, RHIT, is manager of inpatient doding and documentation improvement for University of Utah Health Care. Dr. Vinik is a hospitalist and director of utilization review for the University of Utah Hospital.

As hospitalists, we focus on financial metrics such as length of stay, readmissions, and discharge time to evaluate one’s performance. Since professional billing is usually tied to a hospitalist’s salary, we also learn about CPT coding for professional services. While these are clearly important, our documentation likely has a bigger financial impact on a hospital than do any of these metrics. A little understanding of how a hospital is paid could have huge financial implications to you and your hospital.

Medicare pays for inpatient services based on the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) system. Other federal payers, and the majority of commercial payers, also use a variant of this model for payment. In this model, similar diagnosis codes are grouped into a DRG, and each DRG has a corresponding Relative Weight.

Most important to a hospitalist is how greater documentation specificity changes the DRG to one with a higher weight. Higher weight DRGs reflect sicker patients and also reimburse more. There are two type of comorbidities/complications: minor (CCs) and major (MCCs). Below is an example of how CCs and MCCs affect weight and payment.

Medicare payment follows a basic formula: blended rate x relative weight. A hospital’s blended rate is fixed and is based mostly on factors such as labor costs, inflation, and teaching status. In this example, we used a blended rate of $5,800, which is the average blended rate for hospitals in 2012. In the table above, documenting the likely cause of renal failure more than doubled the hospital reimbursement of the patient with heart failure. Importantly, coders can only code from a provider’s documentation, so if we don’t document the specifics, the coders cannot code it. These same principles hold true to arrive at a case-mix-index (CMI) of your patients – a higher CMI reflects sicker patients and affects publicly reported severity-adjusted outcomes.

There are more than 3,000 minor CCs and 1,400 major MCCs in the code book, but paying attention and documenting a few common conditions will make a huge difference.

Consider this top 10 list for ways to improve your documentation and see what it does to your CMI. Because hospital reimbursement will also increase, you will gain negotiating power with your hospital administrators.

Ten common underdocumented comorbidities

• SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome)/sepsis

• Shock (e.g. septic, cardiogenic, etc).

• Encephalopathy

• AIDS

• Obesity

• Acute renal failure likely caused by [specific condition]

• Anemia/pancytopenia from chemotherapy

• Chronic respiratory failure

• Severe malnutrition

• Heart failure

a. acute vs. chronic

b. systolic vs. diastolic

Dr. Pendleton is chief medical quality officer for University of Utah Health Care, Salt Lake City, and a member of the Hospitalist News advisory board. Michelle Knuckles, RHIT, is manager of inpatient doding and documentation improvement for University of Utah Health Care. Dr. Vinik is a hospitalist and director of utilization review for the University of Utah Hospital.

Michelle Knuckles, RHIT , coding,

Michelle Knuckles, RHIT , coding,