User login

In the beginning phases of the Ebola evolution in the U.S., when Thomas Duncan was declared the first probable case on U.S. soil, many American hospitals were left scared and wondering if they could adequately care for a patient with such a highly contagious infectious disease. Uneasy thoughts swirled around individual practitioners’ minds about whether they would be willing and able to safely provide care to a patient with a devastating, highly infectious disease that has a touted 50% to 70% mortality rate.

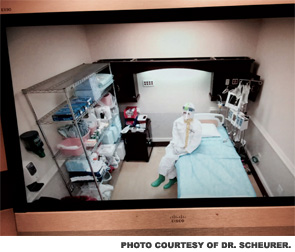

Although a handful of biohazard units in the U.S. had undertaken such care, they had done so in a true biohazard unit, which had been meticulously planned and funded for years and featured a highly trained and skilled staff of physicians, nurses, and others. Nonetheless, with the realization that U.S. hospitals would not get to choose whether or not a patient with Ebola was presented to them, massive planning ensued in thousands of U.S. hospitals.

Within days, hospitals quickly rolled out visible signage and appropriate screening tools to quickly and efficiently identify and isolate the next contagious patient on U.S. soil. As the healthcare workers at Texas Presbyterian Hospital diligently cared for Thomas Duncan, U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers were faced with the sobering reality that a healthcare worker had been infected with the deadly virus.

This was not a case of a medical missionary working in a third world country with limited protective equipment and in unsanitary conditions. This was a highly skilled nurse, with (what was at the time considered to be) adequate protective equipment, who was stricken with a highly lethal disease in the course of nursing care in a U.S. hospital.

Ebola became the leading headline for every news organization in the U.S. and beyond, causing confusion and concern among the lay public. Within U.S. healthcare systems, the signs and symptoms of Ebola began to roll easily off the tongues of both clinical and nonclinical staff, all of whom quickly became well versed on the geography of West Africa.

What happened next in the U.S. healthcare system was a dizzying series of recommendations and changes at the local, regional, and national level. This was accompanied by another sobering realization: Most U.S. hospitals are not able and should not attempt to handle patients infected with Ebola.

The concept of regionalization of Ebola care was quickly accepted as a viable model, as many U.S. hospitals did not have the volunteer workforce, facilities, disaster preparedness infrastructure, protective equipment, or training infrastructure to safely care for such a patient, even if only short-term care was required.

These regionalization efforts required unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospital systems and created the need for complex interdependencies among federal and state agencies across the nation. Many hospitals, including my own, invested thousands of man-hours and significant fiscal resources in preparing for the possibility of an infected patient.

These efforts also prompted a series of uncomfortable conversations, especially among clinicians and bioethicists, about what level of care can be safely provided to an Ebola patient in the U.S. Clinicians and bioethicists came to the realization that an Ebola patient in the U.S. may receive a different standard of care than a patient with a different blood-borne infectious disease. The guiding principle of “staff safety first” made for further difficult conversations among clinicians, who are accustomed to putting their safety second.

With all these perturbations to the system and anxiety-laden clinical discussions, the question is, has any good occurred as a result of this viral penetration into the U.S.? I believe the answer is yes, as the rapid anticipation and planning for this level of care has spurned efforts that otherwise would have remained dormant, including:

- Unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospitals for aiding and assisting each others’ readiness to screen accurately and safely provide first responder care;

- Remarkable cooperation and assistance from state and federal agencies in guidance, communication, and preparedness for the centers designated as regional referral centers;

- Enhanced planning and capabilities for U.S. hospitals to respond and adapt to changes in the external environment, which makes them that much more prepared to respond and adapt to the next contagious disease crisis, one that will undoubtedly occur; and

- A renewed sense of volunteerism among many clinicians, despite the possibility of personal threat.

Current estimates predict the Ebola outbreak will expand from hundreds to thousands of new cases (and deaths) per month.1 As this situation evolves, individual regionalized centers in the U.S. become more prepared (logistically and psychologically) to handle Ebola as each day passes.

The foundational structure of care designed during this outbreak can and should put the U.S. in a very good position to resiliently and effectively care for any highly contagious agent in the future. So in the face of this disruptive adversity, we should all be able to keep calm and Ebola on.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

Reference

In the beginning phases of the Ebola evolution in the U.S., when Thomas Duncan was declared the first probable case on U.S. soil, many American hospitals were left scared and wondering if they could adequately care for a patient with such a highly contagious infectious disease. Uneasy thoughts swirled around individual practitioners’ minds about whether they would be willing and able to safely provide care to a patient with a devastating, highly infectious disease that has a touted 50% to 70% mortality rate.

Although a handful of biohazard units in the U.S. had undertaken such care, they had done so in a true biohazard unit, which had been meticulously planned and funded for years and featured a highly trained and skilled staff of physicians, nurses, and others. Nonetheless, with the realization that U.S. hospitals would not get to choose whether or not a patient with Ebola was presented to them, massive planning ensued in thousands of U.S. hospitals.

Within days, hospitals quickly rolled out visible signage and appropriate screening tools to quickly and efficiently identify and isolate the next contagious patient on U.S. soil. As the healthcare workers at Texas Presbyterian Hospital diligently cared for Thomas Duncan, U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers were faced with the sobering reality that a healthcare worker had been infected with the deadly virus.

This was not a case of a medical missionary working in a third world country with limited protective equipment and in unsanitary conditions. This was a highly skilled nurse, with (what was at the time considered to be) adequate protective equipment, who was stricken with a highly lethal disease in the course of nursing care in a U.S. hospital.

Ebola became the leading headline for every news organization in the U.S. and beyond, causing confusion and concern among the lay public. Within U.S. healthcare systems, the signs and symptoms of Ebola began to roll easily off the tongues of both clinical and nonclinical staff, all of whom quickly became well versed on the geography of West Africa.

What happened next in the U.S. healthcare system was a dizzying series of recommendations and changes at the local, regional, and national level. This was accompanied by another sobering realization: Most U.S. hospitals are not able and should not attempt to handle patients infected with Ebola.

The concept of regionalization of Ebola care was quickly accepted as a viable model, as many U.S. hospitals did not have the volunteer workforce, facilities, disaster preparedness infrastructure, protective equipment, or training infrastructure to safely care for such a patient, even if only short-term care was required.

These regionalization efforts required unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospital systems and created the need for complex interdependencies among federal and state agencies across the nation. Many hospitals, including my own, invested thousands of man-hours and significant fiscal resources in preparing for the possibility of an infected patient.

These efforts also prompted a series of uncomfortable conversations, especially among clinicians and bioethicists, about what level of care can be safely provided to an Ebola patient in the U.S. Clinicians and bioethicists came to the realization that an Ebola patient in the U.S. may receive a different standard of care than a patient with a different blood-borne infectious disease. The guiding principle of “staff safety first” made for further difficult conversations among clinicians, who are accustomed to putting their safety second.

With all these perturbations to the system and anxiety-laden clinical discussions, the question is, has any good occurred as a result of this viral penetration into the U.S.? I believe the answer is yes, as the rapid anticipation and planning for this level of care has spurned efforts that otherwise would have remained dormant, including:

- Unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospitals for aiding and assisting each others’ readiness to screen accurately and safely provide first responder care;

- Remarkable cooperation and assistance from state and federal agencies in guidance, communication, and preparedness for the centers designated as regional referral centers;

- Enhanced planning and capabilities for U.S. hospitals to respond and adapt to changes in the external environment, which makes them that much more prepared to respond and adapt to the next contagious disease crisis, one that will undoubtedly occur; and

- A renewed sense of volunteerism among many clinicians, despite the possibility of personal threat.

Current estimates predict the Ebola outbreak will expand from hundreds to thousands of new cases (and deaths) per month.1 As this situation evolves, individual regionalized centers in the U.S. become more prepared (logistically and psychologically) to handle Ebola as each day passes.

The foundational structure of care designed during this outbreak can and should put the U.S. in a very good position to resiliently and effectively care for any highly contagious agent in the future. So in the face of this disruptive adversity, we should all be able to keep calm and Ebola on.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

Reference

In the beginning phases of the Ebola evolution in the U.S., when Thomas Duncan was declared the first probable case on U.S. soil, many American hospitals were left scared and wondering if they could adequately care for a patient with such a highly contagious infectious disease. Uneasy thoughts swirled around individual practitioners’ minds about whether they would be willing and able to safely provide care to a patient with a devastating, highly infectious disease that has a touted 50% to 70% mortality rate.

Although a handful of biohazard units in the U.S. had undertaken such care, they had done so in a true biohazard unit, which had been meticulously planned and funded for years and featured a highly trained and skilled staff of physicians, nurses, and others. Nonetheless, with the realization that U.S. hospitals would not get to choose whether or not a patient with Ebola was presented to them, massive planning ensued in thousands of U.S. hospitals.

Within days, hospitals quickly rolled out visible signage and appropriate screening tools to quickly and efficiently identify and isolate the next contagious patient on U.S. soil. As the healthcare workers at Texas Presbyterian Hospital diligently cared for Thomas Duncan, U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers were faced with the sobering reality that a healthcare worker had been infected with the deadly virus.

This was not a case of a medical missionary working in a third world country with limited protective equipment and in unsanitary conditions. This was a highly skilled nurse, with (what was at the time considered to be) adequate protective equipment, who was stricken with a highly lethal disease in the course of nursing care in a U.S. hospital.

Ebola became the leading headline for every news organization in the U.S. and beyond, causing confusion and concern among the lay public. Within U.S. healthcare systems, the signs and symptoms of Ebola began to roll easily off the tongues of both clinical and nonclinical staff, all of whom quickly became well versed on the geography of West Africa.

What happened next in the U.S. healthcare system was a dizzying series of recommendations and changes at the local, regional, and national level. This was accompanied by another sobering realization: Most U.S. hospitals are not able and should not attempt to handle patients infected with Ebola.

The concept of regionalization of Ebola care was quickly accepted as a viable model, as many U.S. hospitals did not have the volunteer workforce, facilities, disaster preparedness infrastructure, protective equipment, or training infrastructure to safely care for such a patient, even if only short-term care was required.

These regionalization efforts required unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospital systems and created the need for complex interdependencies among federal and state agencies across the nation. Many hospitals, including my own, invested thousands of man-hours and significant fiscal resources in preparing for the possibility of an infected patient.

These efforts also prompted a series of uncomfortable conversations, especially among clinicians and bioethicists, about what level of care can be safely provided to an Ebola patient in the U.S. Clinicians and bioethicists came to the realization that an Ebola patient in the U.S. may receive a different standard of care than a patient with a different blood-borne infectious disease. The guiding principle of “staff safety first” made for further difficult conversations among clinicians, who are accustomed to putting their safety second.

With all these perturbations to the system and anxiety-laden clinical discussions, the question is, has any good occurred as a result of this viral penetration into the U.S.? I believe the answer is yes, as the rapid anticipation and planning for this level of care has spurned efforts that otherwise would have remained dormant, including:

- Unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospitals for aiding and assisting each others’ readiness to screen accurately and safely provide first responder care;

- Remarkable cooperation and assistance from state and federal agencies in guidance, communication, and preparedness for the centers designated as regional referral centers;

- Enhanced planning and capabilities for U.S. hospitals to respond and adapt to changes in the external environment, which makes them that much more prepared to respond and adapt to the next contagious disease crisis, one that will undoubtedly occur; and

- A renewed sense of volunteerism among many clinicians, despite the possibility of personal threat.

Current estimates predict the Ebola outbreak will expand from hundreds to thousands of new cases (and deaths) per month.1 As this situation evolves, individual regionalized centers in the U.S. become more prepared (logistically and psychologically) to handle Ebola as each day passes.

The foundational structure of care designed during this outbreak can and should put the U.S. in a very good position to resiliently and effectively care for any highly contagious agent in the future. So in the face of this disruptive adversity, we should all be able to keep calm and Ebola on.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.