User login

For all the purported benefits of the electronic health record (EHR), an unintended adverse effect is “electronic siloing.”

I define electronic siloing as the isolating effect of the EHR on clinical workflow that drives caregivers to work in silos, ie, alone at their workstations, thereby discouraging spontaneous interaction. To the extent that increasing evidence supports the importance of interaction among clinical colleagues and of teamwork to optimize clinical outcomes, electronic siloing threatens optimal practice and quality.

Mindfulness that the EHR can foster siloing will help mitigate the risk, as can novel solutions such as using “viewbox watering holes”1 and embedding secure social messaging functions within the EHR, thereby allowing clinicians to reach out to colleagues with clinical challenges in the moment.

THE EHR BRINGS CHANGES, GOOD AND BAD

The EHR represents a major change in health care, with reported benefits that include standardized ordering, reduced medical errors, embedded protocols for guideline-based care, data access to analyze clinical practice patterns and outcomes, and enhanced communication among colleagues who are geographically separated (eg, virtual consults2). On the basis of these benefits and the federal Medicare and Medicaid financial incentives associated with “meaningful use,” the EHR is being increasingly adopted.3–5

Yet for all these benefits and the promise that technology can enhance interaction among health care providers, unintended risks of the EHR paradoxically threaten optimal clinical care.6 Recognized risks include the threat to care should the EHR fail,6 the time and inefficiency costs of typing and multiple log-ons, and the perpetuation of errors in the medical record caused by the cutting and pasting of clinical notes.

Indeed, a substantial body of literature on sociotechnical interactions—how technology affects human patterns of practice—informs analyses of the impact of changing from a paper medical chart to an EHR.6,8–12 For example, in a review of the impact of computerized physician order entry on inpatient clinical workflow, Niazkhani et al11 noted that computerized ordering can change communication channels and collaboration mechanisms. More specifically, they point out that these systems can “replace interpersonal contacts that may result in fewer opportunities for team-wide negotiations.”11

Similarly, Ash et al8 cited the unintended consequences of patient care information systems, especially increased overreliance on the system to communicate, which can undermine direct communication between healthcare providers.

Finally, Dykstra10 described the “reciprocal impact” of computerized physician order entry systems on communication between physicians and nurses. One observer stated, “[You] start doing physician order entry and direct entry of notes and you move that away from the ward into a room and now you eliminate the sense of team, and the kind of human communication that really was essential… You create physician separation.”10 Taken together, these observations suggest that the EHR and computerized order entry in particular can disrupt interaction between physicians and other health care providers, such as nurses and pharmacists.

BENEFITS OF TEAMWORK

A growing body of evidence indicates that teamwork and collaboration among health care providers—which involve frequent, critical face-to-face interaction—has clinical benefit. Demonstrated benefits of teamwork in health care11 include lower surgical and intensive care unit mortality rates, fewer errors in emergency room management, better neonatal resuscitation, and enhanced diagnostic accuracy in interpreting images and biopsies.12,13

As a specific example of the benefits of face-to-face conversation for interpreting chest images, O’Donovan et al14 showed that the diagnostic accuracy of a pulmonologist and thoracic radiologist in assessing rounded atelectasis was better when they reviewed chest CT scans together than when they interpreted the images solo.

Similarly, Flaherty et al15 showed that the level of agreement among pulmonologists, chest radiologists, and lung pathologists progressively increased as interaction and conversation increased when assessing the etiology of patients’ interstitial lung diseases.

As yet another demonstrable benefit of teamwork that should command interest in the current reimbursement-attentive era, analyses by Press Ganey16 and by Gallup have shown that the single best correlate of high patient satisfaction scores regarding hospitalization (including Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems ratings) is patients’ perception that their caregivers functioned as a team serving their needs.

The current perspective extends this observation about the unintended adverse effects of the EHR by suggesting that the EHR can inadvertently lessen spontaneous interaction between physicians as they care for outpatients. I have proposed the term electronic siloing to reflect the isolating impact of the EHR on clinical workflow that drives caregivers to work alone at their workstations, thereby discouraging spontaneous interaction between colleagues (eg, between primary care physicians and subspecialists, and between subspecialists in different disciplines). Because spontaneous face-to-face encounters and conversations among clinicians can encourage clinical insights that benefit patient care, electronic siloing can undermine optimal care. My thesis here is that the EHR predisposes to electronic siloing and that the solution is to first recognize and then to design care to prevent this effect.

DECLINE OF THE ‘CURBSIDE’ CONSULT

How does the subtle but sinister effect of electronic siloing really manifest itself at the bedside? I’ll offer an example from my personal clinical experience and then review similar examples from other clinical settings.

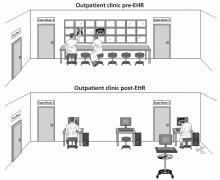

First, consider the following real change in clinical workflow that was caused by implementing the EHR in a pulmonary outpatient clinic and its impact on clinical hallway discussions among pulmonologists caring for their outpatients (Figure 1).

The pre-EHR scene was a straight corridor of examination rooms with a long desk outside the rooms and a bank of x-ray viewboxes where clinicians would review films, gather their thoughts, and write notes before re-entering the patient’s room to discuss recommendations. This scene was undoubtedly common in outpatient clinics of all types around the world.

In the bygone era of paper charting and printed x-ray films, the pulmonologists seeing their patients in examination rooms along this corridor and seated next to one another while they wrote their notes would frequently turn to a colleague seated next to them and request a “curbside” consult, ie, an opinion on the films and the case. Typically, a brief, spontaneous conversation would follow, either confirming the requester’s impressions or raising some new, unconsidered approaches. The effect of these brief, spontaneous conversations was either a new diagnostic or treatment consideration or enhanced clinician confidence in the current plan of care. Each outcome has great merit.

Now consider the same scenario in the EHR era. Printed films and viewboxes are gone (which has the benefits of lower production cost and better film retrieval), and images are now reviewed digitally on computer workstations. Workstations are characteristically spread out along the corridor at distances or may be mounted on mobile platforms. Often, physicians now retreat to their nearby offices to write notes, allowing easier access to workstations or to use voice transcription software to record notes. The net effect of this physical separation and of the subtle but powerful change in workflow is that spontaneous curbside consults over a chest film are less likely to occur and, to the extent that such interactions enhance diagnostic accuracy, beneficial face-to-face clinical discussions are less likely. This is the risk of electronic siloing realized.

Defenders of the EHR will point out that the EHR does not preclude such face-to-face encounters. While technically this is correct, it is also equally true that such encounters are less likely because they no longer flow naturally from the workflow of writing a note side-by-side with colleagues with the films displayed nearby. Pressured for time, clinicians learn efficiency of motion and are simply less likely to leave their workstations to seek another colleague who, in turn, may be tethered to a workstation and absorbed in keyboarding and monitor-watching. The net effect is that such spontaneous face-to-face encounters are clearly less common in the EHR era.

Electronic siloing undoubtedly occurs in many other outpatient and inpatient settings in other specialties. For example, consults between orthopedic surgeons seeing outpatients must be similarly affected, as might be discussions between pathologists reviewing tissue slides on a multiheaded microscope vs individually at their own microscopes or work stations. Indeed, observations that computerized order entry isolates physicians from nurses and that the EHR undermines communication between inpatient health care providers6,8–11 represent other manifestations of electronic siloing.

Another variant of siloing occurs when there are not enough computers to go around. When clinicians seek but cannot find available workstations on the hospital ward, they move from the ward to their offices or other locations, separating them from the nurses and other physicians caring for those patients and, thereby, creating isolation and another form of siloing. A related theme is the importance of architecture in driving desirable interactions in the workplace in general and in hospitals in particular,17,18 where interchanges between health care providers are critical to enhancing quality of care.

OUT OF THE SILO, INTO THE FIELD

So, given the many clear benefits of the EHR and its current wave of adoption in health care, how can we maximize the benefits of the EHR while minimizing the adverse effects of electronic siloing?

The key point is that we must realize, appreciate, and prioritize the value of face-toface interaction among providers as we try to offer optimal care to patients with ever more complex clinical problems.

In doing so, clinical workspaces and the number and placement of workstations must be designed with an explicit intent and priority to encourage interchange between providers and to avoid electronic siloing. As an example related to reviewing images, imaging suites and clinics should be designed with the concept of a viewbox watering hole1 in which clinicians arrayed in a common space could review images on their individual computers but could easily prompt colleagues and send an image to a large, centrally visible monitor for the group’s review and comment. Furthermore, the EHR workflows themselves should drive caregivers to the patient rather than requiring their attention to the keyboard and the monitor. One could also imagine embedding secure social messaging within the EHR to encourage interactions among clinicians about pressing clinical challenges they are facing in the moment.

Overall, only through mindfulness of electronic siloing and of its subtle but adverse effects will we break out of the silos and emerge onto the fields of optimal health care.

- Saunder BF. CT Suite: The Work of Diagnosis in the Age of Noninvasive Cutting. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2008.

- Palen TE, Price D, Shetterly S, Wallace KB. Comparing virtual consults to traditional consults using an electronic health record: an observational case-control study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012; 12:65.

- Black AD, Car J, Pagliari C, et al. The impact of eHealth on the quality and safety of health care: a systematic overview. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1000387.

- Goldzweig CL, Towfigh A, Maglione M, Shekelle PG. Costs and benefits of health information technology: new trends from the literature. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009; 28:w282–w293.

- Police RL, Foster T, Wong KS. Adoption and use of health information technology in physician practice organisations: systematic review. Inform Prim Care 2010; 18:245–258.

- Holroyd-Leduc JM, Lorenzetti D, Straus SE, Sykes L, Quan H. The impact of the electronic medical record on structure, process, and outcomes within primary care: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011; 18:732–737.

- Bohmer RM, McFarlan FW, Adler-Milstein JR. Information technology and clinical operations at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Harvard Business School 2007; Case 607-150.

- Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004; 11:104–112.

- Berg M, Toussaint P. The mantra of modeling and the forgotten powers of paper: a sociotechnical view on the development of process-oriented ICT in health care. Int J Med Inform 2003; 69:223–234.

- Dykstra R. Computerized physician order entry and communication: reciprocal impacts. Proc AMIA Symp 2002:230–234.

- Niazkhani Z, Pirnejad H, Berg M, Aarts J. The impact of computerized provider order entry systems on inpatient clinical workflow: a literature review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009; 16:539–549.

- Carayon P. Human factors of complex sociotechnical systems. Appl Ergon 2006; 37:525–535.

- Wheeler D, Stoller JK. Teamwork, teambuilding and leadership in respiratory and health care. Can J Resp Ther 2011; 47. 1:6–11.

- O’Donovan PB, Schenk M, Lim K, Obuchowski N, Stoller JK. Evaluation of the reliability of computed tomographic criteria used in the diagnosis of round atelectasis. J Thorac Imaging 1997; 12:54–58.

- Flaherty KR, King TE, Raghu G, et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: what is the effect of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170:904–910.

- Press Ganey Associates, Inc. Press Ganey mean score correlations to HCAHPS “Rate Hospital 0-10.” 2010. http://www.pressganey.com/ourSolutions/hospitalSettings/satisfactionPerformanceSuite/HCAHPS_Insights.aspx. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- Stoller JK. A physician’s view of hospital design. The impact of verticality on interaction. Architecture 1988; 77:121–122.

- Becker FD, Steele F, editors. Workplace by Design: Mapping the High-Performance Workplace. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1995.

For all the purported benefits of the electronic health record (EHR), an unintended adverse effect is “electronic siloing.”

I define electronic siloing as the isolating effect of the EHR on clinical workflow that drives caregivers to work in silos, ie, alone at their workstations, thereby discouraging spontaneous interaction. To the extent that increasing evidence supports the importance of interaction among clinical colleagues and of teamwork to optimize clinical outcomes, electronic siloing threatens optimal practice and quality.

Mindfulness that the EHR can foster siloing will help mitigate the risk, as can novel solutions such as using “viewbox watering holes”1 and embedding secure social messaging functions within the EHR, thereby allowing clinicians to reach out to colleagues with clinical challenges in the moment.

THE EHR BRINGS CHANGES, GOOD AND BAD

The EHR represents a major change in health care, with reported benefits that include standardized ordering, reduced medical errors, embedded protocols for guideline-based care, data access to analyze clinical practice patterns and outcomes, and enhanced communication among colleagues who are geographically separated (eg, virtual consults2). On the basis of these benefits and the federal Medicare and Medicaid financial incentives associated with “meaningful use,” the EHR is being increasingly adopted.3–5

Yet for all these benefits and the promise that technology can enhance interaction among health care providers, unintended risks of the EHR paradoxically threaten optimal clinical care.6 Recognized risks include the threat to care should the EHR fail,6 the time and inefficiency costs of typing and multiple log-ons, and the perpetuation of errors in the medical record caused by the cutting and pasting of clinical notes.

Indeed, a substantial body of literature on sociotechnical interactions—how technology affects human patterns of practice—informs analyses of the impact of changing from a paper medical chart to an EHR.6,8–12 For example, in a review of the impact of computerized physician order entry on inpatient clinical workflow, Niazkhani et al11 noted that computerized ordering can change communication channels and collaboration mechanisms. More specifically, they point out that these systems can “replace interpersonal contacts that may result in fewer opportunities for team-wide negotiations.”11

Similarly, Ash et al8 cited the unintended consequences of patient care information systems, especially increased overreliance on the system to communicate, which can undermine direct communication between healthcare providers.

Finally, Dykstra10 described the “reciprocal impact” of computerized physician order entry systems on communication between physicians and nurses. One observer stated, “[You] start doing physician order entry and direct entry of notes and you move that away from the ward into a room and now you eliminate the sense of team, and the kind of human communication that really was essential… You create physician separation.”10 Taken together, these observations suggest that the EHR and computerized order entry in particular can disrupt interaction between physicians and other health care providers, such as nurses and pharmacists.

BENEFITS OF TEAMWORK

A growing body of evidence indicates that teamwork and collaboration among health care providers—which involve frequent, critical face-to-face interaction—has clinical benefit. Demonstrated benefits of teamwork in health care11 include lower surgical and intensive care unit mortality rates, fewer errors in emergency room management, better neonatal resuscitation, and enhanced diagnostic accuracy in interpreting images and biopsies.12,13

As a specific example of the benefits of face-to-face conversation for interpreting chest images, O’Donovan et al14 showed that the diagnostic accuracy of a pulmonologist and thoracic radiologist in assessing rounded atelectasis was better when they reviewed chest CT scans together than when they interpreted the images solo.

Similarly, Flaherty et al15 showed that the level of agreement among pulmonologists, chest radiologists, and lung pathologists progressively increased as interaction and conversation increased when assessing the etiology of patients’ interstitial lung diseases.

As yet another demonstrable benefit of teamwork that should command interest in the current reimbursement-attentive era, analyses by Press Ganey16 and by Gallup have shown that the single best correlate of high patient satisfaction scores regarding hospitalization (including Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems ratings) is patients’ perception that their caregivers functioned as a team serving their needs.

The current perspective extends this observation about the unintended adverse effects of the EHR by suggesting that the EHR can inadvertently lessen spontaneous interaction between physicians as they care for outpatients. I have proposed the term electronic siloing to reflect the isolating impact of the EHR on clinical workflow that drives caregivers to work alone at their workstations, thereby discouraging spontaneous interaction between colleagues (eg, between primary care physicians and subspecialists, and between subspecialists in different disciplines). Because spontaneous face-to-face encounters and conversations among clinicians can encourage clinical insights that benefit patient care, electronic siloing can undermine optimal care. My thesis here is that the EHR predisposes to electronic siloing and that the solution is to first recognize and then to design care to prevent this effect.

DECLINE OF THE ‘CURBSIDE’ CONSULT

How does the subtle but sinister effect of electronic siloing really manifest itself at the bedside? I’ll offer an example from my personal clinical experience and then review similar examples from other clinical settings.

First, consider the following real change in clinical workflow that was caused by implementing the EHR in a pulmonary outpatient clinic and its impact on clinical hallway discussions among pulmonologists caring for their outpatients (Figure 1).

The pre-EHR scene was a straight corridor of examination rooms with a long desk outside the rooms and a bank of x-ray viewboxes where clinicians would review films, gather their thoughts, and write notes before re-entering the patient’s room to discuss recommendations. This scene was undoubtedly common in outpatient clinics of all types around the world.

In the bygone era of paper charting and printed x-ray films, the pulmonologists seeing their patients in examination rooms along this corridor and seated next to one another while they wrote their notes would frequently turn to a colleague seated next to them and request a “curbside” consult, ie, an opinion on the films and the case. Typically, a brief, spontaneous conversation would follow, either confirming the requester’s impressions or raising some new, unconsidered approaches. The effect of these brief, spontaneous conversations was either a new diagnostic or treatment consideration or enhanced clinician confidence in the current plan of care. Each outcome has great merit.

Now consider the same scenario in the EHR era. Printed films and viewboxes are gone (which has the benefits of lower production cost and better film retrieval), and images are now reviewed digitally on computer workstations. Workstations are characteristically spread out along the corridor at distances or may be mounted on mobile platforms. Often, physicians now retreat to their nearby offices to write notes, allowing easier access to workstations or to use voice transcription software to record notes. The net effect of this physical separation and of the subtle but powerful change in workflow is that spontaneous curbside consults over a chest film are less likely to occur and, to the extent that such interactions enhance diagnostic accuracy, beneficial face-to-face clinical discussions are less likely. This is the risk of electronic siloing realized.

Defenders of the EHR will point out that the EHR does not preclude such face-to-face encounters. While technically this is correct, it is also equally true that such encounters are less likely because they no longer flow naturally from the workflow of writing a note side-by-side with colleagues with the films displayed nearby. Pressured for time, clinicians learn efficiency of motion and are simply less likely to leave their workstations to seek another colleague who, in turn, may be tethered to a workstation and absorbed in keyboarding and monitor-watching. The net effect is that such spontaneous face-to-face encounters are clearly less common in the EHR era.

Electronic siloing undoubtedly occurs in many other outpatient and inpatient settings in other specialties. For example, consults between orthopedic surgeons seeing outpatients must be similarly affected, as might be discussions between pathologists reviewing tissue slides on a multiheaded microscope vs individually at their own microscopes or work stations. Indeed, observations that computerized order entry isolates physicians from nurses and that the EHR undermines communication between inpatient health care providers6,8–11 represent other manifestations of electronic siloing.

Another variant of siloing occurs when there are not enough computers to go around. When clinicians seek but cannot find available workstations on the hospital ward, they move from the ward to their offices or other locations, separating them from the nurses and other physicians caring for those patients and, thereby, creating isolation and another form of siloing. A related theme is the importance of architecture in driving desirable interactions in the workplace in general and in hospitals in particular,17,18 where interchanges between health care providers are critical to enhancing quality of care.

OUT OF THE SILO, INTO THE FIELD

So, given the many clear benefits of the EHR and its current wave of adoption in health care, how can we maximize the benefits of the EHR while minimizing the adverse effects of electronic siloing?

The key point is that we must realize, appreciate, and prioritize the value of face-toface interaction among providers as we try to offer optimal care to patients with ever more complex clinical problems.

In doing so, clinical workspaces and the number and placement of workstations must be designed with an explicit intent and priority to encourage interchange between providers and to avoid electronic siloing. As an example related to reviewing images, imaging suites and clinics should be designed with the concept of a viewbox watering hole1 in which clinicians arrayed in a common space could review images on their individual computers but could easily prompt colleagues and send an image to a large, centrally visible monitor for the group’s review and comment. Furthermore, the EHR workflows themselves should drive caregivers to the patient rather than requiring their attention to the keyboard and the monitor. One could also imagine embedding secure social messaging within the EHR to encourage interactions among clinicians about pressing clinical challenges they are facing in the moment.

Overall, only through mindfulness of electronic siloing and of its subtle but adverse effects will we break out of the silos and emerge onto the fields of optimal health care.

For all the purported benefits of the electronic health record (EHR), an unintended adverse effect is “electronic siloing.”

I define electronic siloing as the isolating effect of the EHR on clinical workflow that drives caregivers to work in silos, ie, alone at their workstations, thereby discouraging spontaneous interaction. To the extent that increasing evidence supports the importance of interaction among clinical colleagues and of teamwork to optimize clinical outcomes, electronic siloing threatens optimal practice and quality.

Mindfulness that the EHR can foster siloing will help mitigate the risk, as can novel solutions such as using “viewbox watering holes”1 and embedding secure social messaging functions within the EHR, thereby allowing clinicians to reach out to colleagues with clinical challenges in the moment.

THE EHR BRINGS CHANGES, GOOD AND BAD

The EHR represents a major change in health care, with reported benefits that include standardized ordering, reduced medical errors, embedded protocols for guideline-based care, data access to analyze clinical practice patterns and outcomes, and enhanced communication among colleagues who are geographically separated (eg, virtual consults2). On the basis of these benefits and the federal Medicare and Medicaid financial incentives associated with “meaningful use,” the EHR is being increasingly adopted.3–5

Yet for all these benefits and the promise that technology can enhance interaction among health care providers, unintended risks of the EHR paradoxically threaten optimal clinical care.6 Recognized risks include the threat to care should the EHR fail,6 the time and inefficiency costs of typing and multiple log-ons, and the perpetuation of errors in the medical record caused by the cutting and pasting of clinical notes.

Indeed, a substantial body of literature on sociotechnical interactions—how technology affects human patterns of practice—informs analyses of the impact of changing from a paper medical chart to an EHR.6,8–12 For example, in a review of the impact of computerized physician order entry on inpatient clinical workflow, Niazkhani et al11 noted that computerized ordering can change communication channels and collaboration mechanisms. More specifically, they point out that these systems can “replace interpersonal contacts that may result in fewer opportunities for team-wide negotiations.”11

Similarly, Ash et al8 cited the unintended consequences of patient care information systems, especially increased overreliance on the system to communicate, which can undermine direct communication between healthcare providers.

Finally, Dykstra10 described the “reciprocal impact” of computerized physician order entry systems on communication between physicians and nurses. One observer stated, “[You] start doing physician order entry and direct entry of notes and you move that away from the ward into a room and now you eliminate the sense of team, and the kind of human communication that really was essential… You create physician separation.”10 Taken together, these observations suggest that the EHR and computerized order entry in particular can disrupt interaction between physicians and other health care providers, such as nurses and pharmacists.

BENEFITS OF TEAMWORK

A growing body of evidence indicates that teamwork and collaboration among health care providers—which involve frequent, critical face-to-face interaction—has clinical benefit. Demonstrated benefits of teamwork in health care11 include lower surgical and intensive care unit mortality rates, fewer errors in emergency room management, better neonatal resuscitation, and enhanced diagnostic accuracy in interpreting images and biopsies.12,13

As a specific example of the benefits of face-to-face conversation for interpreting chest images, O’Donovan et al14 showed that the diagnostic accuracy of a pulmonologist and thoracic radiologist in assessing rounded atelectasis was better when they reviewed chest CT scans together than when they interpreted the images solo.

Similarly, Flaherty et al15 showed that the level of agreement among pulmonologists, chest radiologists, and lung pathologists progressively increased as interaction and conversation increased when assessing the etiology of patients’ interstitial lung diseases.

As yet another demonstrable benefit of teamwork that should command interest in the current reimbursement-attentive era, analyses by Press Ganey16 and by Gallup have shown that the single best correlate of high patient satisfaction scores regarding hospitalization (including Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems ratings) is patients’ perception that their caregivers functioned as a team serving their needs.

The current perspective extends this observation about the unintended adverse effects of the EHR by suggesting that the EHR can inadvertently lessen spontaneous interaction between physicians as they care for outpatients. I have proposed the term electronic siloing to reflect the isolating impact of the EHR on clinical workflow that drives caregivers to work alone at their workstations, thereby discouraging spontaneous interaction between colleagues (eg, between primary care physicians and subspecialists, and between subspecialists in different disciplines). Because spontaneous face-to-face encounters and conversations among clinicians can encourage clinical insights that benefit patient care, electronic siloing can undermine optimal care. My thesis here is that the EHR predisposes to electronic siloing and that the solution is to first recognize and then to design care to prevent this effect.

DECLINE OF THE ‘CURBSIDE’ CONSULT

How does the subtle but sinister effect of electronic siloing really manifest itself at the bedside? I’ll offer an example from my personal clinical experience and then review similar examples from other clinical settings.

First, consider the following real change in clinical workflow that was caused by implementing the EHR in a pulmonary outpatient clinic and its impact on clinical hallway discussions among pulmonologists caring for their outpatients (Figure 1).

The pre-EHR scene was a straight corridor of examination rooms with a long desk outside the rooms and a bank of x-ray viewboxes where clinicians would review films, gather their thoughts, and write notes before re-entering the patient’s room to discuss recommendations. This scene was undoubtedly common in outpatient clinics of all types around the world.

In the bygone era of paper charting and printed x-ray films, the pulmonologists seeing their patients in examination rooms along this corridor and seated next to one another while they wrote their notes would frequently turn to a colleague seated next to them and request a “curbside” consult, ie, an opinion on the films and the case. Typically, a brief, spontaneous conversation would follow, either confirming the requester’s impressions or raising some new, unconsidered approaches. The effect of these brief, spontaneous conversations was either a new diagnostic or treatment consideration or enhanced clinician confidence in the current plan of care. Each outcome has great merit.

Now consider the same scenario in the EHR era. Printed films and viewboxes are gone (which has the benefits of lower production cost and better film retrieval), and images are now reviewed digitally on computer workstations. Workstations are characteristically spread out along the corridor at distances or may be mounted on mobile platforms. Often, physicians now retreat to their nearby offices to write notes, allowing easier access to workstations or to use voice transcription software to record notes. The net effect of this physical separation and of the subtle but powerful change in workflow is that spontaneous curbside consults over a chest film are less likely to occur and, to the extent that such interactions enhance diagnostic accuracy, beneficial face-to-face clinical discussions are less likely. This is the risk of electronic siloing realized.

Defenders of the EHR will point out that the EHR does not preclude such face-to-face encounters. While technically this is correct, it is also equally true that such encounters are less likely because they no longer flow naturally from the workflow of writing a note side-by-side with colleagues with the films displayed nearby. Pressured for time, clinicians learn efficiency of motion and are simply less likely to leave their workstations to seek another colleague who, in turn, may be tethered to a workstation and absorbed in keyboarding and monitor-watching. The net effect is that such spontaneous face-to-face encounters are clearly less common in the EHR era.

Electronic siloing undoubtedly occurs in many other outpatient and inpatient settings in other specialties. For example, consults between orthopedic surgeons seeing outpatients must be similarly affected, as might be discussions between pathologists reviewing tissue slides on a multiheaded microscope vs individually at their own microscopes or work stations. Indeed, observations that computerized order entry isolates physicians from nurses and that the EHR undermines communication between inpatient health care providers6,8–11 represent other manifestations of electronic siloing.

Another variant of siloing occurs when there are not enough computers to go around. When clinicians seek but cannot find available workstations on the hospital ward, they move from the ward to their offices or other locations, separating them from the nurses and other physicians caring for those patients and, thereby, creating isolation and another form of siloing. A related theme is the importance of architecture in driving desirable interactions in the workplace in general and in hospitals in particular,17,18 where interchanges between health care providers are critical to enhancing quality of care.

OUT OF THE SILO, INTO THE FIELD

So, given the many clear benefits of the EHR and its current wave of adoption in health care, how can we maximize the benefits of the EHR while minimizing the adverse effects of electronic siloing?

The key point is that we must realize, appreciate, and prioritize the value of face-toface interaction among providers as we try to offer optimal care to patients with ever more complex clinical problems.

In doing so, clinical workspaces and the number and placement of workstations must be designed with an explicit intent and priority to encourage interchange between providers and to avoid electronic siloing. As an example related to reviewing images, imaging suites and clinics should be designed with the concept of a viewbox watering hole1 in which clinicians arrayed in a common space could review images on their individual computers but could easily prompt colleagues and send an image to a large, centrally visible monitor for the group’s review and comment. Furthermore, the EHR workflows themselves should drive caregivers to the patient rather than requiring their attention to the keyboard and the monitor. One could also imagine embedding secure social messaging within the EHR to encourage interactions among clinicians about pressing clinical challenges they are facing in the moment.

Overall, only through mindfulness of electronic siloing and of its subtle but adverse effects will we break out of the silos and emerge onto the fields of optimal health care.

- Saunder BF. CT Suite: The Work of Diagnosis in the Age of Noninvasive Cutting. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2008.

- Palen TE, Price D, Shetterly S, Wallace KB. Comparing virtual consults to traditional consults using an electronic health record: an observational case-control study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012; 12:65.

- Black AD, Car J, Pagliari C, et al. The impact of eHealth on the quality and safety of health care: a systematic overview. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1000387.

- Goldzweig CL, Towfigh A, Maglione M, Shekelle PG. Costs and benefits of health information technology: new trends from the literature. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009; 28:w282–w293.

- Police RL, Foster T, Wong KS. Adoption and use of health information technology in physician practice organisations: systematic review. Inform Prim Care 2010; 18:245–258.

- Holroyd-Leduc JM, Lorenzetti D, Straus SE, Sykes L, Quan H. The impact of the electronic medical record on structure, process, and outcomes within primary care: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011; 18:732–737.

- Bohmer RM, McFarlan FW, Adler-Milstein JR. Information technology and clinical operations at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Harvard Business School 2007; Case 607-150.

- Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004; 11:104–112.

- Berg M, Toussaint P. The mantra of modeling and the forgotten powers of paper: a sociotechnical view on the development of process-oriented ICT in health care. Int J Med Inform 2003; 69:223–234.

- Dykstra R. Computerized physician order entry and communication: reciprocal impacts. Proc AMIA Symp 2002:230–234.

- Niazkhani Z, Pirnejad H, Berg M, Aarts J. The impact of computerized provider order entry systems on inpatient clinical workflow: a literature review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009; 16:539–549.

- Carayon P. Human factors of complex sociotechnical systems. Appl Ergon 2006; 37:525–535.

- Wheeler D, Stoller JK. Teamwork, teambuilding and leadership in respiratory and health care. Can J Resp Ther 2011; 47. 1:6–11.

- O’Donovan PB, Schenk M, Lim K, Obuchowski N, Stoller JK. Evaluation of the reliability of computed tomographic criteria used in the diagnosis of round atelectasis. J Thorac Imaging 1997; 12:54–58.

- Flaherty KR, King TE, Raghu G, et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: what is the effect of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170:904–910.

- Press Ganey Associates, Inc. Press Ganey mean score correlations to HCAHPS “Rate Hospital 0-10.” 2010. http://www.pressganey.com/ourSolutions/hospitalSettings/satisfactionPerformanceSuite/HCAHPS_Insights.aspx. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- Stoller JK. A physician’s view of hospital design. The impact of verticality on interaction. Architecture 1988; 77:121–122.

- Becker FD, Steele F, editors. Workplace by Design: Mapping the High-Performance Workplace. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1995.

- Saunder BF. CT Suite: The Work of Diagnosis in the Age of Noninvasive Cutting. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2008.

- Palen TE, Price D, Shetterly S, Wallace KB. Comparing virtual consults to traditional consults using an electronic health record: an observational case-control study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012; 12:65.

- Black AD, Car J, Pagliari C, et al. The impact of eHealth on the quality and safety of health care: a systematic overview. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1000387.

- Goldzweig CL, Towfigh A, Maglione M, Shekelle PG. Costs and benefits of health information technology: new trends from the literature. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009; 28:w282–w293.

- Police RL, Foster T, Wong KS. Adoption and use of health information technology in physician practice organisations: systematic review. Inform Prim Care 2010; 18:245–258.

- Holroyd-Leduc JM, Lorenzetti D, Straus SE, Sykes L, Quan H. The impact of the electronic medical record on structure, process, and outcomes within primary care: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011; 18:732–737.

- Bohmer RM, McFarlan FW, Adler-Milstein JR. Information technology and clinical operations at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Harvard Business School 2007; Case 607-150.

- Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004; 11:104–112.

- Berg M, Toussaint P. The mantra of modeling and the forgotten powers of paper: a sociotechnical view on the development of process-oriented ICT in health care. Int J Med Inform 2003; 69:223–234.

- Dykstra R. Computerized physician order entry and communication: reciprocal impacts. Proc AMIA Symp 2002:230–234.

- Niazkhani Z, Pirnejad H, Berg M, Aarts J. The impact of computerized provider order entry systems on inpatient clinical workflow: a literature review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009; 16:539–549.

- Carayon P. Human factors of complex sociotechnical systems. Appl Ergon 2006; 37:525–535.

- Wheeler D, Stoller JK. Teamwork, teambuilding and leadership in respiratory and health care. Can J Resp Ther 2011; 47. 1:6–11.

- O’Donovan PB, Schenk M, Lim K, Obuchowski N, Stoller JK. Evaluation of the reliability of computed tomographic criteria used in the diagnosis of round atelectasis. J Thorac Imaging 1997; 12:54–58.

- Flaherty KR, King TE, Raghu G, et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: what is the effect of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170:904–910.

- Press Ganey Associates, Inc. Press Ganey mean score correlations to HCAHPS “Rate Hospital 0-10.” 2010. http://www.pressganey.com/ourSolutions/hospitalSettings/satisfactionPerformanceSuite/HCAHPS_Insights.aspx. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- Stoller JK. A physician’s view of hospital design. The impact of verticality on interaction. Architecture 1988; 77:121–122.

- Becker FD, Steele F, editors. Workplace by Design: Mapping the High-Performance Workplace. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1995.