User login

In October 1998, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) was funded and established. This center is the federal government’s lead agency for scientific research on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and is 1 of the 27 institutes and centers that make up the National Institutes of Health. The mission of the NCCAM is to define, through rigorous scientific investigation, the usefulness and safety of CAM interventions and roles in improving health and health care.

Although a significant number of adults in the U.S. use some form of CAM, physicians rarely recommend these therapies to their patients, and their use is limited in conventional medical settings.1-3 This is often attributed to a lack of knowledge or scientific evidence, despite a belief by many providers of the potential positive effects.3

In an attempt to disseminate knowledge about various CAM therapies investigated by NCCAM, the Complementary and Alternative Resources to Enhance Satisfaction (CARES) program was organized as a resource center at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center (VAMC). It was anticipated that increasing knowledge about CAM and offering these therapies in conjunction with the conventional medical practices at the VAMC would lead to a more comprehensive, patient-centered system of care. In this way, the goal was to transform current thinking from a focus solely on treating the patient’s disease to a holistic approach, which encompassed comfort, family support, and quality of life (QOL).

Background

The number of veterans with chronic illnesses and pain continues to rise. While aggressive efforts have been aimed at safely decreasing pain and discomfort, many veterans report dissatisfaction with traditional treatment methods, which focus on drug therapy and have little emphasis on preventive or holistic care.4 Health care providers often share patients’ frustrations regarding the use of medications that have varying degrees of efficacy and multiple adverse effects. Innovative approaches to improving health and decreasing pain and stress have focused on more holistic and patient-centered philosophies of care. However, there have been few studies to assess feasibility, implementation, and outcomes within an established medical center.

As an ideal goal among patients, families, and HCPs in all care settings, patient-centered care has become a more prominent focus of the VA health care system (VAHCS). The incorporation of patient-centered care, along with an electronic medical record, structural transformation, and greater focus on performance accountability have contributed to dramatic improvements in care within the VAHCS in the past decade.5,6 Mounting evidence continues to validate the positive health outcomes of models of care that engage patients and families with valuable roles in the healing process.7,8 Professional caregiver satisfaction has also been linked to increased patient satisfaction.9

Integral to patient-centered care is the ability of caregivers to see the whole person—body, mind, and soul. The implementation of therapies or environments that complement traditional medicine and provide for physical comfort and pain management can be important in achieving this form of holistic medicine.1,10 By definition, CAM is any method used outside of and in addition to conventional medicine to prevent or treat disease.6 As CAM takes a holistic approach to healing, most therapies involve not only the treatment of the symptoms of the illness, but also the development of a method of healing that focuses on the spiritual and emotional origins from which the illness arises.11

According to the National Health Interview Survey, complementary and alternative therapies were used by one-third of adults in the U.S. in 2002 and by 4 in 10 adults in 2007.11 However, these estimates may be conservative, as other studies have found that at least the majority of adults had used some form of CAM at one time.1 The most common CAM therapies used by adults in 2007 were nonvitamin, nonmineral, natural products, such as fish oil or ginseng; deep breathing exercises; meditation; chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation; massage; and yoga.11 In 2007, adults most commonly used CAM to treat a variety of musculoskeletal problems (ie, back, neck, or joint pain).11

As a patient-centered philosophy, the most general benefit of the use of CAM involves the idea of patient empowerment and participation in the healing process. Many therapies, such as tai chi, meditation, and guided imagery, require active patient involvement, which can encourage feelings of self-control over the disease process. Complementary and alternative medicine has been shown to be effective in decreasing pain, anxiety, stress, and nausea.10,12-14 Increasing evidence supports an association between stress or negative emotions and health outcomes, such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease.15,16 When used in conjunction with traditional medical treatment, CAM can help patients cope with devastating symptoms of their disease processes or to avoid some symptoms altogether.

Despite the widespread use of CAM therapies by the public, HCPs rarely recommend CAM therapies to their patients.2,3 This has been attributed to a lack of scientific evidence, a lack of knowledge or comfort, and a lack of an available CAM provider.3 The basic philosophy of self-motivated stress and pain management, which is fundamental to most CAM therapies, is learned and embraced by most HCPs, but the implementation is not often seen in the real world of busy clinical practice. With its numerous benefits, CAM has the potential to significantly improve the health and QOL. Therefore, innovative programs that help HCPs become knowledgeable and competent in incorporating CAM into current systems of care are needed.

In 2010, the Cleveland VAMC was funded through the Innovations in Patient-Centered Care grant to design and implement a complementary therapy resource center. This project was the CARES program and was organized through the Cleveland Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC). The project team included researchers and clinicians within the GRECC as well as other clinical departments. A CAM coordinator was hired to organize lectures, order supplies, and network with various departments within the Cleveland VAMC. Additionally, a major focus of the CARES program was to encourage the involvement of family and friends in the care of the veteran. An integral goal of this project was to bring CAM resources to the bedside of veterans in acute and long-term care on a 24/7 basis.

The rationale for the implementation of a complementary therapy resource center was based on the Planetree model of patient-centered care, which encourages healing in all dimensions and the integration of complementary therapies with conventional medical practices.17 Offering such therapies in an established medical center with knowledgeable HCPs may increase the safety of such use.1 Providing workshops and lectures for HCPs about various complementary therapies would help educate them and provide them with a knowledge base to feel comfortable in recommending therapies to their patients. By opening workshops and lectures about CAM to the public, veterans would be given the opportunity to learn about the therapies available and their efficacy.

Advancing Patient QOL

The Cleveland VAMC has a history of research and policies to advance a culture of patient-centered care with an emphasis on QOL, customer service, and the use of CAM.In 2001, Anthony D’Eramo, a member of the Cleveland VAMC GRECC, developed a program to educate nursing assistants at the Cleveland and Chillicothe VAMCs on complementary therapies, including meditation, spirituality, therapeutic touch, and yoga. The overall response to the program was positive.18 The focus of the training was on the QOL of nursing assistants; most found participation in the training to be a valuable and worthwhile experience. They indicated their intent to use the techniques they learned for themselves, their families, and their patients.18

Also in 2001, researchers at the Cleveland and Pittsburgh VAMCs identified that older veterans with osteoarthritis perceived the use of prayer and meditation as more useful than medications or surgery for the treatment of pain associated with osteoarthritis.19 Since that time, the Cleveland VAMC has worked with the Pittsburgh VAMC to study the use of motivational interviewing—a communication technique that focuses on patient engagement to achieve changes in behavior—for patients with knee osteoarthritis to consider total knee replacement surgery.

In 2004, Antall and Kresevic implemented a program of guided imagery for patients undergoing joint replacement surgery.20 Although the sample size was small, results indicated positive trends for pain relief, decreased anxiety, and decreased length of stay following surgery. Due to the small sample size, statistical comparisons were not performed; however, the mean pain medication use in the 4 days following surgery was morphine 84.76 mg in the control group vs 36.7 mg in the guided imagery group.20 The overall response to the guided imagery tapes was positive, with 75% of the subjects indicating that use of the tapes made them feel more relaxed and decreased their pain.

More recently, the clinical nurse specialist group at the Cleveland VAMC began a study using music and education to decrease pain. In 2009, a Patient-Centered Care Council was established for the medical center to advance a culture of patient-centered care by analyzing the results of performance measures and satisfaction reports. Additionally, the nursing staff at the Cleveland VAMC Community Living Center (CLC) expressed an interest in expanding the use of CAM by creating a wellness center with exercise equipment and aromatherapy. This center was well-received but had only limited access to patients in acute and long-term care and was unable to be sustained due to insufficient staffing.

The CARES Program

The objectives of the CARES program were to (1) change the culture of the medical center to a more holistic approach, encouraging family and patient participation in care and emphasizing comfort and satisfaction; (2) increase knowledge of complementary therapies for relaxation; (3) improve patient and family satisfaction with nursing and medical care; and (4) build on preexisting medical center initiatives for patient-centered care.

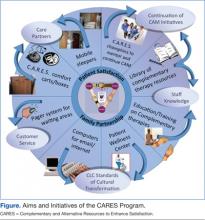

The CARES program presented lectures and training workshops on various CAM therapies for all HCPs in order to provide useful information that may not otherwise have been available. Evidence has shown that those who receive training for complementary therapies respond positively and view the experience as valuable.18 It was hoped that these training sessions would empower nurses and other health care staff to provide care while recognizing the importance of treating the entire person. Programs were planned for various times of the day and evening in various patient care locations. (Aims and initiatives of the CARES program are further expanded in the Figure.)

Prior to any educational sessions, a survey was distributed to HCPs about their knowledge and experience with CAM. Though responses to the survey were limited, the results indicate interest in learning more about CAM therapies (Table 1).

Over the course of the yearlong grant, a total of 19 workshops were scheduled and held for HCPs and veterans for a total of 346 participants. This included 3 intensive training sessions for staff, 1 on Reiki and 2 on Healing Touch. All programs, including the intensive training sessions, were available free to participants. Some of the sessions were videotaped and archived for later viewing. (See Table 2 for a list of all training sessions provided by the CARES program.) The project was limited in both time and funds, so only a limited number of topics were able to be covered, and the topics were based mostly on the availability of experts in each field.

Resources

In addition to lectures, organizers of the CARES program purchased 20 comfort carts for inpatient units at the Cleveland VAMC. These were small rolling lockable wooden carts approved by Interior Design, who evaluated and designed previous work spaces at the Cleveland VAMC to make them functional, appealing, and well-suited for the veterans. The carts were stocked with various resources that focused on comfort and entertainment. Specifically related to CAM, these carts contained guided imagery CDs and Playaways. (Playaways are small audio players with included earbud headphones meant for individual use, which are preloaded with a specific guided imagery session.) Additionally, the comfort carts contained books, books on tape, magazines, portable CD players, music CDs, games, exercise bands, healthy snacks, DVDs, and a portable DVD player. Other items purchased to be distributed to various inpatient and outpatient units included Nintendo Wii game consoles and small televisions. Mobile sleepers were purchased for inpatient units to encourage extended-family visitation. These sleepers have been widely adopted throughout the medical center.

Additional resources purchased by the CARES program included educational pamphlets on various health issues affecting veterans, such as the management of stress. In an effort to increase patient education about complementary therapies, the CARES program provided funding for 2 dedicated channels on the patient television system, broadcasting 24-hour, evidence-based relaxation and guided imagery programming. Finally, the CARES program enhanced the Wellness Center begun by the nurses in the CLC. This included the purchase of exercise equipment, computers, aromatherapy, massage tables, and massage cushions. The exercise equipment, including a recumbent stepper, recumbent bike, and treadmill, was provided by funds from the CARES project. The equipment was available 24/7 to veterans and could be accessed once the veteran was cleared by his primary care and admitting physician. Competencies were developed and completed by the staff. The competencies included orienting the patient on use of the equipment, observation and documentation of equipment used, and response. Veterans who had established home exercise routines were able to continue their programs while hospitalized in the CLC. This helped maintain and regain leisure activity and promoted wellness.

Program Outcomes

Evaluations of the training sessions were overwhelmingly positive (Table 3), and many individuals requested further education and training. A total of 204 participants (59%) completed posttraining evaluations. Some common themes identified through comments on program evaluations included requests for training in the evenings and on weekends. Of the 329 HCPs who participated, 36.5% were nurses or nurse practitioners, 13.7% were ancillary staff (eg, nursing assistants), 9.7% were social workers, 8.5% were students, 5.8% were physicians or physician assistants, 5.2% were psychiatry staff members, 4.9% were occupational/physical/recreational therapy staff members, and 15.7% were other/unknown. The remaining 17 individuals who participated were veterans and their family members.

Reiki and guided imagery classes for increasing relaxation and comfort are still offered to veterans. An attendee of the initial level 1 training offered from the first grant progressed in certifications and received Master status. This Master has trained 60% of the nurses in her unit in level 1 Reiki. Weekly sessions are being implemented for veterans. Guided imagery training provided by the initial CARES grant project is sustained via weekly groups. Reports of an increased sense of well-being and relaxation as well as relief from chronic pain have been reported.

Although evaluations were created for the comfort carts, they were not regularly completed by patients. However, direct subjective feedback from nursing staff who spoke to organizers of the project about both the beds and the carts was very positive. Additionally, members of the project were able to talk to some veterans and family members who agreed to discuss their use of these items. They expressed appreciation for the snacks, which helped “tide them over,” and the beds, which allowed them to stay and comfortably visit their sick loved ones. Utilization of the CARES comfort carts and mobile sleepers on the inpatient units continued after completion of this study. The GRECC has continued to function as a resource center by distributing educational materials, restocking the comfort carts, and providing educational programs on CAM.

Objectively measuring satisfaction related to the implementation of the program proved challenging. At program commencement, plans involved an evaluation of the CARES program using overall hospital satisfaction measures. However, different components of the program took effect at different times, and not all components affected all parts of the hospital. Satisfaction measures, such as the National Veteran’s Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP) and the local Quick-Kards, which report aggregate scores for patient satisfaction, were analyzed prior, during, and after program implementation but could not be clearly correlated to program impact on patient and family satisfaction with health care. Additionally, the categories addressed in the surveys were very broad while the CARES program addressed only some aspects of hospital care. Despite the weak correlation, SHEP results of inpatient services were analyzed and evaluations did increase in the categories of inpatient overall quality and shared decision making from prior-to-program implementation to postprogram implementation. Quick-Kard results remained essentially the same related to patient-provider communication pre- and postprogram implementation. Additional quantitative and qualitative measures of satisfaction linked specifically to program components need to be created or further explored.

Limitations

This project was not able to address all aspects of the wide range of topics under the general term CAM. In a short time, many individuals taught courses in their areas of expertise. However, many areas, such as acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation, and massage therapy, were not included. Additionally, although herbal therapies are likely the most used CAM method, they also present many challenges when combined with medications and other common therapies among veteran patients.11 The study was not intended to provide any general information endorsing the safety of these herbal therapies when combined with medications, so this topic was avoided altogether. However, this is a topic that needs further exploration and medical involvement, as these therapies can have medical consequences despite their casual use and availability.

Conclusions

The most important lesson learned through this program was that CAM is a very “hot topic” at the Cleveland VAMC and many staff members are enthusiastic and open to integrating it into their practice. This was important throughout program implementation as staff buy-in is integral to a successful medical center initiative. Veterans and family members were receptive to learning about CAM and participating in programs. An abundance of local experts outside of the facility were also willing to share their knowledge about their particular therapy.

Securing continuing education (CE) credit hours was challenging, requiring applications and close work with presenters. However, the added benefit of CE credits helped to garner an audience. Marketing the programs in a time sensitive nature to allow staff or family members to arrange schedules was critical.

Multiple opportunities, including initiatives for patient-centered care, CLCs, and management of veterans with pain and delirium can be helpful for maintaining and expanding the CARES program. Most important, it was learned that a small group of clinicians who can think outside the box can make a big difference for veterans. Implementing a holistic and patient-centered program of CAM that brings resources to veterans 24/7 is both feasible and fun.

Future Directions

Plans for future educational programs on CAM will include the use of interactive audio/video technology to expand outreach, yet still allow the active participation of HCPs and possibly veterans. Cleveland VAMC GRECC staff members continue to work on various aspects of the CARES program, such as the use of audio tapes for relaxation and augmentation of pain treatment and to support the Wellness Center. The carts and mobile sleepers are still heavily used to support the “Care Partners” program at the Cleveland VAMC, and they continue to be stocked with items. These items helped meet the project’s goal of providing resources to be available 24/7.

The CARES program and aspects of CAM have continued to be marketed at professional educational activities and to veterans at health fairs at the medical center. Additional funding sources and small grants have helped to sustain the educational programs and restock the carts, particularly the current VA-funded T21 grant to manage patients with delirium. Future funding opportunities continue to be explored. Additionally future directions would include the incorporation of various other methods of CAM, which were unable to be explored in this time-limited project, including acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation, and massage therapy.

Though evaluations of educational programs were very positive and subjective feedback from the use of the carts and mobile sleepers was positive, it was not possible to establish a direct correlation between improved patient and family satisfaction and health care. Future directions of program evaluation should focus on objective measurements, which can be directly linked to program impact on satisfaction. It is hoped that the inclusion of CAM will contribute to continued improvements in quality and patient satisfaction throughout the entire VAHCS.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript and the program described are the results of work funded by the VHA Innovations for Patient Centered Care and supported by the use of resources and facilities at the Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, specifically, the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

References

1. Vohra S, Feldman K, Johnston B, Waters K, Boon H. Integrating complementary and alternative medicine into academic medical centers: Experience and perceptions of nine leading centers in North America. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:78-84.

2. Kurtz ME, Nolan RB, Rittinger WJ. Primary care physicians’ attitudes and practices regarding complementary and alternative medicine. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103(12):597-602.

3. Wahner-Roedler DL, Vincent A, Elkin PL, Loehrer LL, Cha SS, Bauer BA. Physician’s attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine and their knowledge of specific therapies: A survey at an academic medical center. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3(4):495-501.

4. Kroesen K, Baldwin CM, Brooks AJ, Bell IR. U.S. military veterans’ perceptions of the conventional medical care system and their use of complementary and alternative medicine. Fam Pract. 2002;19(1):57-64.

5. Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(22):2218-2227.

6. Perlin JB, Kolodner RM, Roswell RH. The Veterans Health Administration: Quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11, pt 2):828-836.

7. Covinsky KE, Goldman L, Cook EF, et al. The impact of serious illness on patients’ families. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. JAMA. 1994;272(23):1839-1844.

8. Cullen L, Titler M, Drahozal R. Family and pet visitation in the critical care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2003;23(5):62-67.

9. Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(2):122-128.

10. Kreitzer MJ, Snyder M. Healing the heart: Integrating complementary therapies and healing practices into the care of cardiovascular patients. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;17(2):73-80.

11. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;12:1-23.

12. Wang C, Collet JP, Lau J. The effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(5):493-501.

13. Gregory S, Verdouw J. Therapeutic touch: Its application for residents in aged care. Aust Nurs J. 2005;12(7):23-25.

14. Hilliard RE. Music therapy in hospice and palliative care: A review of empirical data. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2(2):173-178.

15. Jonas BS, Lando JF. Negative affect as a prospective risk factor for hypertension. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(2):188-196.

16. Fredrickson BL, Levenson RW. Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cogn Emot. 1998;12(2):191-220.

17. Katz DL, Ali A. Integrating complementary and alternative practices into conventional care. In: Frampton SB, Charmel P, eds. Putting Patients First: Best Practices in Patient-Centered Care. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

18. D’Eramo AL, Papp KK, Rose JH. A program on complementary therapies for long-term care nursing assistants. Geriatr Nurs. 2001;22(4):201-207.

19. Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Variation in perceptions of treatment and self-care practices in elderly with osteoarthritis: A comparison between African American and white patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(4):340-345.

20. Antall GF, Kresevic D. The use of guided imagery to manage pain in an elderly orthopaedic population. Orthop Nurs. 2004;23(5):335-340.

In October 1998, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) was funded and established. This center is the federal government’s lead agency for scientific research on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and is 1 of the 27 institutes and centers that make up the National Institutes of Health. The mission of the NCCAM is to define, through rigorous scientific investigation, the usefulness and safety of CAM interventions and roles in improving health and health care.

Although a significant number of adults in the U.S. use some form of CAM, physicians rarely recommend these therapies to their patients, and their use is limited in conventional medical settings.1-3 This is often attributed to a lack of knowledge or scientific evidence, despite a belief by many providers of the potential positive effects.3

In an attempt to disseminate knowledge about various CAM therapies investigated by NCCAM, the Complementary and Alternative Resources to Enhance Satisfaction (CARES) program was organized as a resource center at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center (VAMC). It was anticipated that increasing knowledge about CAM and offering these therapies in conjunction with the conventional medical practices at the VAMC would lead to a more comprehensive, patient-centered system of care. In this way, the goal was to transform current thinking from a focus solely on treating the patient’s disease to a holistic approach, which encompassed comfort, family support, and quality of life (QOL).

Background

The number of veterans with chronic illnesses and pain continues to rise. While aggressive efforts have been aimed at safely decreasing pain and discomfort, many veterans report dissatisfaction with traditional treatment methods, which focus on drug therapy and have little emphasis on preventive or holistic care.4 Health care providers often share patients’ frustrations regarding the use of medications that have varying degrees of efficacy and multiple adverse effects. Innovative approaches to improving health and decreasing pain and stress have focused on more holistic and patient-centered philosophies of care. However, there have been few studies to assess feasibility, implementation, and outcomes within an established medical center.

As an ideal goal among patients, families, and HCPs in all care settings, patient-centered care has become a more prominent focus of the VA health care system (VAHCS). The incorporation of patient-centered care, along with an electronic medical record, structural transformation, and greater focus on performance accountability have contributed to dramatic improvements in care within the VAHCS in the past decade.5,6 Mounting evidence continues to validate the positive health outcomes of models of care that engage patients and families with valuable roles in the healing process.7,8 Professional caregiver satisfaction has also been linked to increased patient satisfaction.9

Integral to patient-centered care is the ability of caregivers to see the whole person—body, mind, and soul. The implementation of therapies or environments that complement traditional medicine and provide for physical comfort and pain management can be important in achieving this form of holistic medicine.1,10 By definition, CAM is any method used outside of and in addition to conventional medicine to prevent or treat disease.6 As CAM takes a holistic approach to healing, most therapies involve not only the treatment of the symptoms of the illness, but also the development of a method of healing that focuses on the spiritual and emotional origins from which the illness arises.11

According to the National Health Interview Survey, complementary and alternative therapies were used by one-third of adults in the U.S. in 2002 and by 4 in 10 adults in 2007.11 However, these estimates may be conservative, as other studies have found that at least the majority of adults had used some form of CAM at one time.1 The most common CAM therapies used by adults in 2007 were nonvitamin, nonmineral, natural products, such as fish oil or ginseng; deep breathing exercises; meditation; chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation; massage; and yoga.11 In 2007, adults most commonly used CAM to treat a variety of musculoskeletal problems (ie, back, neck, or joint pain).11

As a patient-centered philosophy, the most general benefit of the use of CAM involves the idea of patient empowerment and participation in the healing process. Many therapies, such as tai chi, meditation, and guided imagery, require active patient involvement, which can encourage feelings of self-control over the disease process. Complementary and alternative medicine has been shown to be effective in decreasing pain, anxiety, stress, and nausea.10,12-14 Increasing evidence supports an association between stress or negative emotions and health outcomes, such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease.15,16 When used in conjunction with traditional medical treatment, CAM can help patients cope with devastating symptoms of their disease processes or to avoid some symptoms altogether.

Despite the widespread use of CAM therapies by the public, HCPs rarely recommend CAM therapies to their patients.2,3 This has been attributed to a lack of scientific evidence, a lack of knowledge or comfort, and a lack of an available CAM provider.3 The basic philosophy of self-motivated stress and pain management, which is fundamental to most CAM therapies, is learned and embraced by most HCPs, but the implementation is not often seen in the real world of busy clinical practice. With its numerous benefits, CAM has the potential to significantly improve the health and QOL. Therefore, innovative programs that help HCPs become knowledgeable and competent in incorporating CAM into current systems of care are needed.

In 2010, the Cleveland VAMC was funded through the Innovations in Patient-Centered Care grant to design and implement a complementary therapy resource center. This project was the CARES program and was organized through the Cleveland Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC). The project team included researchers and clinicians within the GRECC as well as other clinical departments. A CAM coordinator was hired to organize lectures, order supplies, and network with various departments within the Cleveland VAMC. Additionally, a major focus of the CARES program was to encourage the involvement of family and friends in the care of the veteran. An integral goal of this project was to bring CAM resources to the bedside of veterans in acute and long-term care on a 24/7 basis.

The rationale for the implementation of a complementary therapy resource center was based on the Planetree model of patient-centered care, which encourages healing in all dimensions and the integration of complementary therapies with conventional medical practices.17 Offering such therapies in an established medical center with knowledgeable HCPs may increase the safety of such use.1 Providing workshops and lectures for HCPs about various complementary therapies would help educate them and provide them with a knowledge base to feel comfortable in recommending therapies to their patients. By opening workshops and lectures about CAM to the public, veterans would be given the opportunity to learn about the therapies available and their efficacy.

Advancing Patient QOL

The Cleveland VAMC has a history of research and policies to advance a culture of patient-centered care with an emphasis on QOL, customer service, and the use of CAM.In 2001, Anthony D’Eramo, a member of the Cleveland VAMC GRECC, developed a program to educate nursing assistants at the Cleveland and Chillicothe VAMCs on complementary therapies, including meditation, spirituality, therapeutic touch, and yoga. The overall response to the program was positive.18 The focus of the training was on the QOL of nursing assistants; most found participation in the training to be a valuable and worthwhile experience. They indicated their intent to use the techniques they learned for themselves, their families, and their patients.18

Also in 2001, researchers at the Cleveland and Pittsburgh VAMCs identified that older veterans with osteoarthritis perceived the use of prayer and meditation as more useful than medications or surgery for the treatment of pain associated with osteoarthritis.19 Since that time, the Cleveland VAMC has worked with the Pittsburgh VAMC to study the use of motivational interviewing—a communication technique that focuses on patient engagement to achieve changes in behavior—for patients with knee osteoarthritis to consider total knee replacement surgery.

In 2004, Antall and Kresevic implemented a program of guided imagery for patients undergoing joint replacement surgery.20 Although the sample size was small, results indicated positive trends for pain relief, decreased anxiety, and decreased length of stay following surgery. Due to the small sample size, statistical comparisons were not performed; however, the mean pain medication use in the 4 days following surgery was morphine 84.76 mg in the control group vs 36.7 mg in the guided imagery group.20 The overall response to the guided imagery tapes was positive, with 75% of the subjects indicating that use of the tapes made them feel more relaxed and decreased their pain.

More recently, the clinical nurse specialist group at the Cleveland VAMC began a study using music and education to decrease pain. In 2009, a Patient-Centered Care Council was established for the medical center to advance a culture of patient-centered care by analyzing the results of performance measures and satisfaction reports. Additionally, the nursing staff at the Cleveland VAMC Community Living Center (CLC) expressed an interest in expanding the use of CAM by creating a wellness center with exercise equipment and aromatherapy. This center was well-received but had only limited access to patients in acute and long-term care and was unable to be sustained due to insufficient staffing.

The CARES Program

The objectives of the CARES program were to (1) change the culture of the medical center to a more holistic approach, encouraging family and patient participation in care and emphasizing comfort and satisfaction; (2) increase knowledge of complementary therapies for relaxation; (3) improve patient and family satisfaction with nursing and medical care; and (4) build on preexisting medical center initiatives for patient-centered care.

The CARES program presented lectures and training workshops on various CAM therapies for all HCPs in order to provide useful information that may not otherwise have been available. Evidence has shown that those who receive training for complementary therapies respond positively and view the experience as valuable.18 It was hoped that these training sessions would empower nurses and other health care staff to provide care while recognizing the importance of treating the entire person. Programs were planned for various times of the day and evening in various patient care locations. (Aims and initiatives of the CARES program are further expanded in the Figure.)

Prior to any educational sessions, a survey was distributed to HCPs about their knowledge and experience with CAM. Though responses to the survey were limited, the results indicate interest in learning more about CAM therapies (Table 1).

Over the course of the yearlong grant, a total of 19 workshops were scheduled and held for HCPs and veterans for a total of 346 participants. This included 3 intensive training sessions for staff, 1 on Reiki and 2 on Healing Touch. All programs, including the intensive training sessions, were available free to participants. Some of the sessions were videotaped and archived for later viewing. (See Table 2 for a list of all training sessions provided by the CARES program.) The project was limited in both time and funds, so only a limited number of topics were able to be covered, and the topics were based mostly on the availability of experts in each field.

Resources

In addition to lectures, organizers of the CARES program purchased 20 comfort carts for inpatient units at the Cleveland VAMC. These were small rolling lockable wooden carts approved by Interior Design, who evaluated and designed previous work spaces at the Cleveland VAMC to make them functional, appealing, and well-suited for the veterans. The carts were stocked with various resources that focused on comfort and entertainment. Specifically related to CAM, these carts contained guided imagery CDs and Playaways. (Playaways are small audio players with included earbud headphones meant for individual use, which are preloaded with a specific guided imagery session.) Additionally, the comfort carts contained books, books on tape, magazines, portable CD players, music CDs, games, exercise bands, healthy snacks, DVDs, and a portable DVD player. Other items purchased to be distributed to various inpatient and outpatient units included Nintendo Wii game consoles and small televisions. Mobile sleepers were purchased for inpatient units to encourage extended-family visitation. These sleepers have been widely adopted throughout the medical center.

Additional resources purchased by the CARES program included educational pamphlets on various health issues affecting veterans, such as the management of stress. In an effort to increase patient education about complementary therapies, the CARES program provided funding for 2 dedicated channels on the patient television system, broadcasting 24-hour, evidence-based relaxation and guided imagery programming. Finally, the CARES program enhanced the Wellness Center begun by the nurses in the CLC. This included the purchase of exercise equipment, computers, aromatherapy, massage tables, and massage cushions. The exercise equipment, including a recumbent stepper, recumbent bike, and treadmill, was provided by funds from the CARES project. The equipment was available 24/7 to veterans and could be accessed once the veteran was cleared by his primary care and admitting physician. Competencies were developed and completed by the staff. The competencies included orienting the patient on use of the equipment, observation and documentation of equipment used, and response. Veterans who had established home exercise routines were able to continue their programs while hospitalized in the CLC. This helped maintain and regain leisure activity and promoted wellness.

Program Outcomes

Evaluations of the training sessions were overwhelmingly positive (Table 3), and many individuals requested further education and training. A total of 204 participants (59%) completed posttraining evaluations. Some common themes identified through comments on program evaluations included requests for training in the evenings and on weekends. Of the 329 HCPs who participated, 36.5% were nurses or nurse practitioners, 13.7% were ancillary staff (eg, nursing assistants), 9.7% were social workers, 8.5% were students, 5.8% were physicians or physician assistants, 5.2% were psychiatry staff members, 4.9% were occupational/physical/recreational therapy staff members, and 15.7% were other/unknown. The remaining 17 individuals who participated were veterans and their family members.

Reiki and guided imagery classes for increasing relaxation and comfort are still offered to veterans. An attendee of the initial level 1 training offered from the first grant progressed in certifications and received Master status. This Master has trained 60% of the nurses in her unit in level 1 Reiki. Weekly sessions are being implemented for veterans. Guided imagery training provided by the initial CARES grant project is sustained via weekly groups. Reports of an increased sense of well-being and relaxation as well as relief from chronic pain have been reported.

Although evaluations were created for the comfort carts, they were not regularly completed by patients. However, direct subjective feedback from nursing staff who spoke to organizers of the project about both the beds and the carts was very positive. Additionally, members of the project were able to talk to some veterans and family members who agreed to discuss their use of these items. They expressed appreciation for the snacks, which helped “tide them over,” and the beds, which allowed them to stay and comfortably visit their sick loved ones. Utilization of the CARES comfort carts and mobile sleepers on the inpatient units continued after completion of this study. The GRECC has continued to function as a resource center by distributing educational materials, restocking the comfort carts, and providing educational programs on CAM.

Objectively measuring satisfaction related to the implementation of the program proved challenging. At program commencement, plans involved an evaluation of the CARES program using overall hospital satisfaction measures. However, different components of the program took effect at different times, and not all components affected all parts of the hospital. Satisfaction measures, such as the National Veteran’s Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP) and the local Quick-Kards, which report aggregate scores for patient satisfaction, were analyzed prior, during, and after program implementation but could not be clearly correlated to program impact on patient and family satisfaction with health care. Additionally, the categories addressed in the surveys were very broad while the CARES program addressed only some aspects of hospital care. Despite the weak correlation, SHEP results of inpatient services were analyzed and evaluations did increase in the categories of inpatient overall quality and shared decision making from prior-to-program implementation to postprogram implementation. Quick-Kard results remained essentially the same related to patient-provider communication pre- and postprogram implementation. Additional quantitative and qualitative measures of satisfaction linked specifically to program components need to be created or further explored.

Limitations

This project was not able to address all aspects of the wide range of topics under the general term CAM. In a short time, many individuals taught courses in their areas of expertise. However, many areas, such as acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation, and massage therapy, were not included. Additionally, although herbal therapies are likely the most used CAM method, they also present many challenges when combined with medications and other common therapies among veteran patients.11 The study was not intended to provide any general information endorsing the safety of these herbal therapies when combined with medications, so this topic was avoided altogether. However, this is a topic that needs further exploration and medical involvement, as these therapies can have medical consequences despite their casual use and availability.

Conclusions

The most important lesson learned through this program was that CAM is a very “hot topic” at the Cleveland VAMC and many staff members are enthusiastic and open to integrating it into their practice. This was important throughout program implementation as staff buy-in is integral to a successful medical center initiative. Veterans and family members were receptive to learning about CAM and participating in programs. An abundance of local experts outside of the facility were also willing to share their knowledge about their particular therapy.

Securing continuing education (CE) credit hours was challenging, requiring applications and close work with presenters. However, the added benefit of CE credits helped to garner an audience. Marketing the programs in a time sensitive nature to allow staff or family members to arrange schedules was critical.

Multiple opportunities, including initiatives for patient-centered care, CLCs, and management of veterans with pain and delirium can be helpful for maintaining and expanding the CARES program. Most important, it was learned that a small group of clinicians who can think outside the box can make a big difference for veterans. Implementing a holistic and patient-centered program of CAM that brings resources to veterans 24/7 is both feasible and fun.

Future Directions

Plans for future educational programs on CAM will include the use of interactive audio/video technology to expand outreach, yet still allow the active participation of HCPs and possibly veterans. Cleveland VAMC GRECC staff members continue to work on various aspects of the CARES program, such as the use of audio tapes for relaxation and augmentation of pain treatment and to support the Wellness Center. The carts and mobile sleepers are still heavily used to support the “Care Partners” program at the Cleveland VAMC, and they continue to be stocked with items. These items helped meet the project’s goal of providing resources to be available 24/7.

The CARES program and aspects of CAM have continued to be marketed at professional educational activities and to veterans at health fairs at the medical center. Additional funding sources and small grants have helped to sustain the educational programs and restock the carts, particularly the current VA-funded T21 grant to manage patients with delirium. Future funding opportunities continue to be explored. Additionally future directions would include the incorporation of various other methods of CAM, which were unable to be explored in this time-limited project, including acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation, and massage therapy.

Though evaluations of educational programs were very positive and subjective feedback from the use of the carts and mobile sleepers was positive, it was not possible to establish a direct correlation between improved patient and family satisfaction and health care. Future directions of program evaluation should focus on objective measurements, which can be directly linked to program impact on satisfaction. It is hoped that the inclusion of CAM will contribute to continued improvements in quality and patient satisfaction throughout the entire VAHCS.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript and the program described are the results of work funded by the VHA Innovations for Patient Centered Care and supported by the use of resources and facilities at the Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, specifically, the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

References

1. Vohra S, Feldman K, Johnston B, Waters K, Boon H. Integrating complementary and alternative medicine into academic medical centers: Experience and perceptions of nine leading centers in North America. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:78-84.

2. Kurtz ME, Nolan RB, Rittinger WJ. Primary care physicians’ attitudes and practices regarding complementary and alternative medicine. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103(12):597-602.

3. Wahner-Roedler DL, Vincent A, Elkin PL, Loehrer LL, Cha SS, Bauer BA. Physician’s attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine and their knowledge of specific therapies: A survey at an academic medical center. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3(4):495-501.

4. Kroesen K, Baldwin CM, Brooks AJ, Bell IR. U.S. military veterans’ perceptions of the conventional medical care system and their use of complementary and alternative medicine. Fam Pract. 2002;19(1):57-64.

5. Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(22):2218-2227.

6. Perlin JB, Kolodner RM, Roswell RH. The Veterans Health Administration: Quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11, pt 2):828-836.

7. Covinsky KE, Goldman L, Cook EF, et al. The impact of serious illness on patients’ families. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. JAMA. 1994;272(23):1839-1844.

8. Cullen L, Titler M, Drahozal R. Family and pet visitation in the critical care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2003;23(5):62-67.

9. Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(2):122-128.

10. Kreitzer MJ, Snyder M. Healing the heart: Integrating complementary therapies and healing practices into the care of cardiovascular patients. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;17(2):73-80.

11. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;12:1-23.

12. Wang C, Collet JP, Lau J. The effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(5):493-501.

13. Gregory S, Verdouw J. Therapeutic touch: Its application for residents in aged care. Aust Nurs J. 2005;12(7):23-25.

14. Hilliard RE. Music therapy in hospice and palliative care: A review of empirical data. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2(2):173-178.

15. Jonas BS, Lando JF. Negative affect as a prospective risk factor for hypertension. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(2):188-196.

16. Fredrickson BL, Levenson RW. Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cogn Emot. 1998;12(2):191-220.

17. Katz DL, Ali A. Integrating complementary and alternative practices into conventional care. In: Frampton SB, Charmel P, eds. Putting Patients First: Best Practices in Patient-Centered Care. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

18. D’Eramo AL, Papp KK, Rose JH. A program on complementary therapies for long-term care nursing assistants. Geriatr Nurs. 2001;22(4):201-207.

19. Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Variation in perceptions of treatment and self-care practices in elderly with osteoarthritis: A comparison between African American and white patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(4):340-345.

20. Antall GF, Kresevic D. The use of guided imagery to manage pain in an elderly orthopaedic population. Orthop Nurs. 2004;23(5):335-340.

In October 1998, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) was funded and established. This center is the federal government’s lead agency for scientific research on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and is 1 of the 27 institutes and centers that make up the National Institutes of Health. The mission of the NCCAM is to define, through rigorous scientific investigation, the usefulness and safety of CAM interventions and roles in improving health and health care.

Although a significant number of adults in the U.S. use some form of CAM, physicians rarely recommend these therapies to their patients, and their use is limited in conventional medical settings.1-3 This is often attributed to a lack of knowledge or scientific evidence, despite a belief by many providers of the potential positive effects.3

In an attempt to disseminate knowledge about various CAM therapies investigated by NCCAM, the Complementary and Alternative Resources to Enhance Satisfaction (CARES) program was organized as a resource center at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center (VAMC). It was anticipated that increasing knowledge about CAM and offering these therapies in conjunction with the conventional medical practices at the VAMC would lead to a more comprehensive, patient-centered system of care. In this way, the goal was to transform current thinking from a focus solely on treating the patient’s disease to a holistic approach, which encompassed comfort, family support, and quality of life (QOL).

Background

The number of veterans with chronic illnesses and pain continues to rise. While aggressive efforts have been aimed at safely decreasing pain and discomfort, many veterans report dissatisfaction with traditional treatment methods, which focus on drug therapy and have little emphasis on preventive or holistic care.4 Health care providers often share patients’ frustrations regarding the use of medications that have varying degrees of efficacy and multiple adverse effects. Innovative approaches to improving health and decreasing pain and stress have focused on more holistic and patient-centered philosophies of care. However, there have been few studies to assess feasibility, implementation, and outcomes within an established medical center.

As an ideal goal among patients, families, and HCPs in all care settings, patient-centered care has become a more prominent focus of the VA health care system (VAHCS). The incorporation of patient-centered care, along with an electronic medical record, structural transformation, and greater focus on performance accountability have contributed to dramatic improvements in care within the VAHCS in the past decade.5,6 Mounting evidence continues to validate the positive health outcomes of models of care that engage patients and families with valuable roles in the healing process.7,8 Professional caregiver satisfaction has also been linked to increased patient satisfaction.9

Integral to patient-centered care is the ability of caregivers to see the whole person—body, mind, and soul. The implementation of therapies or environments that complement traditional medicine and provide for physical comfort and pain management can be important in achieving this form of holistic medicine.1,10 By definition, CAM is any method used outside of and in addition to conventional medicine to prevent or treat disease.6 As CAM takes a holistic approach to healing, most therapies involve not only the treatment of the symptoms of the illness, but also the development of a method of healing that focuses on the spiritual and emotional origins from which the illness arises.11

According to the National Health Interview Survey, complementary and alternative therapies were used by one-third of adults in the U.S. in 2002 and by 4 in 10 adults in 2007.11 However, these estimates may be conservative, as other studies have found that at least the majority of adults had used some form of CAM at one time.1 The most common CAM therapies used by adults in 2007 were nonvitamin, nonmineral, natural products, such as fish oil or ginseng; deep breathing exercises; meditation; chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation; massage; and yoga.11 In 2007, adults most commonly used CAM to treat a variety of musculoskeletal problems (ie, back, neck, or joint pain).11

As a patient-centered philosophy, the most general benefit of the use of CAM involves the idea of patient empowerment and participation in the healing process. Many therapies, such as tai chi, meditation, and guided imagery, require active patient involvement, which can encourage feelings of self-control over the disease process. Complementary and alternative medicine has been shown to be effective in decreasing pain, anxiety, stress, and nausea.10,12-14 Increasing evidence supports an association between stress or negative emotions and health outcomes, such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease.15,16 When used in conjunction with traditional medical treatment, CAM can help patients cope with devastating symptoms of their disease processes or to avoid some symptoms altogether.

Despite the widespread use of CAM therapies by the public, HCPs rarely recommend CAM therapies to their patients.2,3 This has been attributed to a lack of scientific evidence, a lack of knowledge or comfort, and a lack of an available CAM provider.3 The basic philosophy of self-motivated stress and pain management, which is fundamental to most CAM therapies, is learned and embraced by most HCPs, but the implementation is not often seen in the real world of busy clinical practice. With its numerous benefits, CAM has the potential to significantly improve the health and QOL. Therefore, innovative programs that help HCPs become knowledgeable and competent in incorporating CAM into current systems of care are needed.

In 2010, the Cleveland VAMC was funded through the Innovations in Patient-Centered Care grant to design and implement a complementary therapy resource center. This project was the CARES program and was organized through the Cleveland Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC). The project team included researchers and clinicians within the GRECC as well as other clinical departments. A CAM coordinator was hired to organize lectures, order supplies, and network with various departments within the Cleveland VAMC. Additionally, a major focus of the CARES program was to encourage the involvement of family and friends in the care of the veteran. An integral goal of this project was to bring CAM resources to the bedside of veterans in acute and long-term care on a 24/7 basis.

The rationale for the implementation of a complementary therapy resource center was based on the Planetree model of patient-centered care, which encourages healing in all dimensions and the integration of complementary therapies with conventional medical practices.17 Offering such therapies in an established medical center with knowledgeable HCPs may increase the safety of such use.1 Providing workshops and lectures for HCPs about various complementary therapies would help educate them and provide them with a knowledge base to feel comfortable in recommending therapies to their patients. By opening workshops and lectures about CAM to the public, veterans would be given the opportunity to learn about the therapies available and their efficacy.

Advancing Patient QOL

The Cleveland VAMC has a history of research and policies to advance a culture of patient-centered care with an emphasis on QOL, customer service, and the use of CAM.In 2001, Anthony D’Eramo, a member of the Cleveland VAMC GRECC, developed a program to educate nursing assistants at the Cleveland and Chillicothe VAMCs on complementary therapies, including meditation, spirituality, therapeutic touch, and yoga. The overall response to the program was positive.18 The focus of the training was on the QOL of nursing assistants; most found participation in the training to be a valuable and worthwhile experience. They indicated their intent to use the techniques they learned for themselves, their families, and their patients.18

Also in 2001, researchers at the Cleveland and Pittsburgh VAMCs identified that older veterans with osteoarthritis perceived the use of prayer and meditation as more useful than medications or surgery for the treatment of pain associated with osteoarthritis.19 Since that time, the Cleveland VAMC has worked with the Pittsburgh VAMC to study the use of motivational interviewing—a communication technique that focuses on patient engagement to achieve changes in behavior—for patients with knee osteoarthritis to consider total knee replacement surgery.

In 2004, Antall and Kresevic implemented a program of guided imagery for patients undergoing joint replacement surgery.20 Although the sample size was small, results indicated positive trends for pain relief, decreased anxiety, and decreased length of stay following surgery. Due to the small sample size, statistical comparisons were not performed; however, the mean pain medication use in the 4 days following surgery was morphine 84.76 mg in the control group vs 36.7 mg in the guided imagery group.20 The overall response to the guided imagery tapes was positive, with 75% of the subjects indicating that use of the tapes made them feel more relaxed and decreased their pain.

More recently, the clinical nurse specialist group at the Cleveland VAMC began a study using music and education to decrease pain. In 2009, a Patient-Centered Care Council was established for the medical center to advance a culture of patient-centered care by analyzing the results of performance measures and satisfaction reports. Additionally, the nursing staff at the Cleveland VAMC Community Living Center (CLC) expressed an interest in expanding the use of CAM by creating a wellness center with exercise equipment and aromatherapy. This center was well-received but had only limited access to patients in acute and long-term care and was unable to be sustained due to insufficient staffing.

The CARES Program

The objectives of the CARES program were to (1) change the culture of the medical center to a more holistic approach, encouraging family and patient participation in care and emphasizing comfort and satisfaction; (2) increase knowledge of complementary therapies for relaxation; (3) improve patient and family satisfaction with nursing and medical care; and (4) build on preexisting medical center initiatives for patient-centered care.

The CARES program presented lectures and training workshops on various CAM therapies for all HCPs in order to provide useful information that may not otherwise have been available. Evidence has shown that those who receive training for complementary therapies respond positively and view the experience as valuable.18 It was hoped that these training sessions would empower nurses and other health care staff to provide care while recognizing the importance of treating the entire person. Programs were planned for various times of the day and evening in various patient care locations. (Aims and initiatives of the CARES program are further expanded in the Figure.)

Prior to any educational sessions, a survey was distributed to HCPs about their knowledge and experience with CAM. Though responses to the survey were limited, the results indicate interest in learning more about CAM therapies (Table 1).

Over the course of the yearlong grant, a total of 19 workshops were scheduled and held for HCPs and veterans for a total of 346 participants. This included 3 intensive training sessions for staff, 1 on Reiki and 2 on Healing Touch. All programs, including the intensive training sessions, were available free to participants. Some of the sessions were videotaped and archived for later viewing. (See Table 2 for a list of all training sessions provided by the CARES program.) The project was limited in both time and funds, so only a limited number of topics were able to be covered, and the topics were based mostly on the availability of experts in each field.

Resources

In addition to lectures, organizers of the CARES program purchased 20 comfort carts for inpatient units at the Cleveland VAMC. These were small rolling lockable wooden carts approved by Interior Design, who evaluated and designed previous work spaces at the Cleveland VAMC to make them functional, appealing, and well-suited for the veterans. The carts were stocked with various resources that focused on comfort and entertainment. Specifically related to CAM, these carts contained guided imagery CDs and Playaways. (Playaways are small audio players with included earbud headphones meant for individual use, which are preloaded with a specific guided imagery session.) Additionally, the comfort carts contained books, books on tape, magazines, portable CD players, music CDs, games, exercise bands, healthy snacks, DVDs, and a portable DVD player. Other items purchased to be distributed to various inpatient and outpatient units included Nintendo Wii game consoles and small televisions. Mobile sleepers were purchased for inpatient units to encourage extended-family visitation. These sleepers have been widely adopted throughout the medical center.

Additional resources purchased by the CARES program included educational pamphlets on various health issues affecting veterans, such as the management of stress. In an effort to increase patient education about complementary therapies, the CARES program provided funding for 2 dedicated channels on the patient television system, broadcasting 24-hour, evidence-based relaxation and guided imagery programming. Finally, the CARES program enhanced the Wellness Center begun by the nurses in the CLC. This included the purchase of exercise equipment, computers, aromatherapy, massage tables, and massage cushions. The exercise equipment, including a recumbent stepper, recumbent bike, and treadmill, was provided by funds from the CARES project. The equipment was available 24/7 to veterans and could be accessed once the veteran was cleared by his primary care and admitting physician. Competencies were developed and completed by the staff. The competencies included orienting the patient on use of the equipment, observation and documentation of equipment used, and response. Veterans who had established home exercise routines were able to continue their programs while hospitalized in the CLC. This helped maintain and regain leisure activity and promoted wellness.

Program Outcomes

Evaluations of the training sessions were overwhelmingly positive (Table 3), and many individuals requested further education and training. A total of 204 participants (59%) completed posttraining evaluations. Some common themes identified through comments on program evaluations included requests for training in the evenings and on weekends. Of the 329 HCPs who participated, 36.5% were nurses or nurse practitioners, 13.7% were ancillary staff (eg, nursing assistants), 9.7% were social workers, 8.5% were students, 5.8% were physicians or physician assistants, 5.2% were psychiatry staff members, 4.9% were occupational/physical/recreational therapy staff members, and 15.7% were other/unknown. The remaining 17 individuals who participated were veterans and their family members.

Reiki and guided imagery classes for increasing relaxation and comfort are still offered to veterans. An attendee of the initial level 1 training offered from the first grant progressed in certifications and received Master status. This Master has trained 60% of the nurses in her unit in level 1 Reiki. Weekly sessions are being implemented for veterans. Guided imagery training provided by the initial CARES grant project is sustained via weekly groups. Reports of an increased sense of well-being and relaxation as well as relief from chronic pain have been reported.

Although evaluations were created for the comfort carts, they were not regularly completed by patients. However, direct subjective feedback from nursing staff who spoke to organizers of the project about both the beds and the carts was very positive. Additionally, members of the project were able to talk to some veterans and family members who agreed to discuss their use of these items. They expressed appreciation for the snacks, which helped “tide them over,” and the beds, which allowed them to stay and comfortably visit their sick loved ones. Utilization of the CARES comfort carts and mobile sleepers on the inpatient units continued after completion of this study. The GRECC has continued to function as a resource center by distributing educational materials, restocking the comfort carts, and providing educational programs on CAM.

Objectively measuring satisfaction related to the implementation of the program proved challenging. At program commencement, plans involved an evaluation of the CARES program using overall hospital satisfaction measures. However, different components of the program took effect at different times, and not all components affected all parts of the hospital. Satisfaction measures, such as the National Veteran’s Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP) and the local Quick-Kards, which report aggregate scores for patient satisfaction, were analyzed prior, during, and after program implementation but could not be clearly correlated to program impact on patient and family satisfaction with health care. Additionally, the categories addressed in the surveys were very broad while the CARES program addressed only some aspects of hospital care. Despite the weak correlation, SHEP results of inpatient services were analyzed and evaluations did increase in the categories of inpatient overall quality and shared decision making from prior-to-program implementation to postprogram implementation. Quick-Kard results remained essentially the same related to patient-provider communication pre- and postprogram implementation. Additional quantitative and qualitative measures of satisfaction linked specifically to program components need to be created or further explored.

Limitations

This project was not able to address all aspects of the wide range of topics under the general term CAM. In a short time, many individuals taught courses in their areas of expertise. However, many areas, such as acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation, and massage therapy, were not included. Additionally, although herbal therapies are likely the most used CAM method, they also present many challenges when combined with medications and other common therapies among veteran patients.11 The study was not intended to provide any general information endorsing the safety of these herbal therapies when combined with medications, so this topic was avoided altogether. However, this is a topic that needs further exploration and medical involvement, as these therapies can have medical consequences despite their casual use and availability.

Conclusions

The most important lesson learned through this program was that CAM is a very “hot topic” at the Cleveland VAMC and many staff members are enthusiastic and open to integrating it into their practice. This was important throughout program implementation as staff buy-in is integral to a successful medical center initiative. Veterans and family members were receptive to learning about CAM and participating in programs. An abundance of local experts outside of the facility were also willing to share their knowledge about their particular therapy.

Securing continuing education (CE) credit hours was challenging, requiring applications and close work with presenters. However, the added benefit of CE credits helped to garner an audience. Marketing the programs in a time sensitive nature to allow staff or family members to arrange schedules was critical.

Multiple opportunities, including initiatives for patient-centered care, CLCs, and management of veterans with pain and delirium can be helpful for maintaining and expanding the CARES program. Most important, it was learned that a small group of clinicians who can think outside the box can make a big difference for veterans. Implementing a holistic and patient-centered program of CAM that brings resources to veterans 24/7 is both feasible and fun.

Future Directions

Plans for future educational programs on CAM will include the use of interactive audio/video technology to expand outreach, yet still allow the active participation of HCPs and possibly veterans. Cleveland VAMC GRECC staff members continue to work on various aspects of the CARES program, such as the use of audio tapes for relaxation and augmentation of pain treatment and to support the Wellness Center. The carts and mobile sleepers are still heavily used to support the “Care Partners” program at the Cleveland VAMC, and they continue to be stocked with items. These items helped meet the project’s goal of providing resources to be available 24/7.

The CARES program and aspects of CAM have continued to be marketed at professional educational activities and to veterans at health fairs at the medical center. Additional funding sources and small grants have helped to sustain the educational programs and restock the carts, particularly the current VA-funded T21 grant to manage patients with delirium. Future funding opportunities continue to be explored. Additionally future directions would include the incorporation of various other methods of CAM, which were unable to be explored in this time-limited project, including acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation, and massage therapy.

Though evaluations of educational programs were very positive and subjective feedback from the use of the carts and mobile sleepers was positive, it was not possible to establish a direct correlation between improved patient and family satisfaction and health care. Future directions of program evaluation should focus on objective measurements, which can be directly linked to program impact on satisfaction. It is hoped that the inclusion of CAM will contribute to continued improvements in quality and patient satisfaction throughout the entire VAHCS.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript and the program described are the results of work funded by the VHA Innovations for Patient Centered Care and supported by the use of resources and facilities at the Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, specifically, the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

References

1. Vohra S, Feldman K, Johnston B, Waters K, Boon H. Integrating complementary and alternative medicine into academic medical centers: Experience and perceptions of nine leading centers in North America. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:78-84.

2. Kurtz ME, Nolan RB, Rittinger WJ. Primary care physicians’ attitudes and practices regarding complementary and alternative medicine. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103(12):597-602.

3. Wahner-Roedler DL, Vincent A, Elkin PL, Loehrer LL, Cha SS, Bauer BA. Physician’s attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine and their knowledge of specific therapies: A survey at an academic medical center. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3(4):495-501.

4. Kroesen K, Baldwin CM, Brooks AJ, Bell IR. U.S. military veterans’ perceptions of the conventional medical care system and their use of complementary and alternative medicine. Fam Pract. 2002;19(1):57-64.

5. Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(22):2218-2227.

6. Perlin JB, Kolodner RM, Roswell RH. The Veterans Health Administration: Quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11, pt 2):828-836.

7. Covinsky KE, Goldman L, Cook EF, et al. The impact of serious illness on patients’ families. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. JAMA. 1994;272(23):1839-1844.

8. Cullen L, Titler M, Drahozal R. Family and pet visitation in the critical care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2003;23(5):62-67.

9. Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(2):122-128.

10. Kreitzer MJ, Snyder M. Healing the heart: Integrating complementary therapies and healing practices into the care of cardiovascular patients. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;17(2):73-80.