User login

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by the loss of bone density.1 Bone is normally porous and is in a state of flux due to changes in regeneration caused by osteoclast or osteoblast activity. However, age and other factors can accelerate loss in bone density and lead to decreased bone strength and an increased risk of fracture. In men, bone mineral density (BMD) can begin to decline as early as age 30 to 40 years. By age 80 years, 25% of total bone mass may be lost.2

Of the 44 million Americans with low BMD or osteoporosis, 20% are men.1 This group accounts for up to 40% of all osteoporotic fractures. About 1 in 4 men aged ≥ 50 years may experience a lifetime fracture. Fractures may lead to chronic pain, disability, increased dependence, and potentially death. These complications cause expenditures upward of $4.1 billion annually in North America alone.3,4 About 80,000 US men will experience a hip fracture each year, one-third of whom will die within that year. This constitutes a mortality rate 2 to 3 times higher than that of women. Osteoporosis often goes undiagnosed and untreated due to a lack of symptoms until a fracture occurs, underlining the potential benefit of preemptive screening.

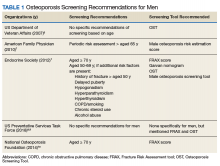

In 2007, Shekell and colleagues outlined how the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) screened men for osteoporosis.5 At the time, 95% of the VA population was male, though it has since dropped to 91%.6 Shekell and colleagues estimated that about 200,0000 to 400,0000 male veterans had osteoporosis.5 Osteoporotic risk factors deemed specific to veterans were excessive alcohol use, spinal cord injury and lack of weight-bearing exercise, prolonged corticosteroid use, and androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer. Different screening techniques were assessed, and the VA recommended the Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST).5 Many organizations have developed clinical guidance, including who should be screened; however, screening for men remains a controversial area due to a lack of any strong recommendations (Table 1).

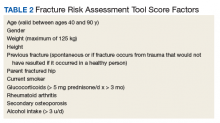

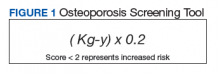

Endocrine Society screening guidelines for men are the most specific: testing BMD in men aged ≥ 70 years, or if aged 50 to 69 years with an additional risk factor (eg, low body weight, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic steroid use).1 The Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX) score is often cited as a common screening tool. It is a free online questionnaire that provides a 10-year probability risk of hip or major osteoporotic fracture.11 However, this tool is limited by age, weight, and the assumption that all questions are answered accurately. Some of the information required includes the presence of a number of risk factors, such as alcohol use, glucocorticoids, and medical history of rheumatoid arthritis, among others (Table 2). The OST score, on the other hand, is a calculation that does not take into account other risk factors (Figure 1). This tool categorizes the patient into low, moderate, or high risk for osteoporosis.8

In a study of 4,000 men aged ≥ 70 years,

A 2017 VA Office of Rural Health study examined the utility of OST to screen referred patients aged > 50 years to receive DEXA scans in patient aligned care team (PACT) clinics at 3 different VA locations.13 The study excluded patients who had been screened previously or treated for osteoporosis, were receiving hospice care; 1 site excluded patients aged > 88 years. Two of the sites also reviewed the patient’s medications to screen for agents that may contribute to increased fracture risk. Veterans identified as high risk were referred for education and offered a DEXA scan and treatment. In total, 867 veterans were screened; 19% (168) were deemed high risk, and 6% (53) underwent DEXA scans. The study noted that only 15 patients had reportable DEXA scans and 10 were positive for bone disease.

As there has been documented success in the PACT setting in implementing standardized protocols for screening and treating veterans, it is reasonable to extend the concept into other VA services. The home-based primary care (HBPC) population is especially vulnerable due to the age of patients, limited weight-bearing exercise to improve bone strength, and limited access to DEXA scans due to difficulty traveling outside of the home. Despite these issues, a goal of the HBPC service is to provide continual care for veterans and improve their health so they may return to the community setting. As a result, patients are followed frequently, providing many opportunities for interventions. This study aims to determine the proportion of HBPC patients who are at high risk for osteoporosis and can receive a DEXA scan for evaluation.

Methods

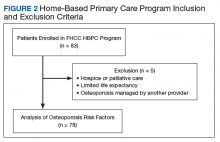

This study was a retrospective chart analysis using descriptive statistics. It was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center (FHCC). Patients were included in the study if they were enrolled in the HBPC program at FHCC. Patients were excluded if they were receiving hospice or palliative care, had a limited life expectancy per the HBPC provider, or had a diagnosis of osteoporosis that was being managed by a VA endocrinologist, rheumatologist, or non-VA provider.

The study was conducted from February 1, 2018, through November 30, 2018. All chart reviews were done through the FHCC electronic health record. A minimum of 80 and maximum of 150 charts were reviewed as this was the typical patient volume in the HBPC program. Basic demographic information was collected and analyzed by calculating FRAX and OST scores. With the results, patients were classified as low or high risk of developing osteoporosis, and whether a DEXA scan should be recommended.

Results

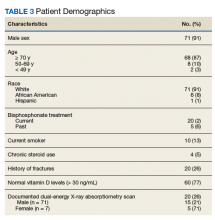

After chart review, 83 patients were enrolled in the FHCC HBPC program during the study period. Out of these, 5 patients were excluded due to hospice or palliative care status, limited life expectancy, or had their osteoporosis managed by another non-HBPC provider. As a result, 78 patients were analyzed to determine their risk of osteoporosis (Figure 2). Most of the patients were white males with a median age of 82 years. A majority of the patients did not have any current or previous treatment with bisphosphonates, 77% had normal vitamin D levels, and only 13% (10) were current smokers; of the male patients only 21% (15) had a previous DEXA scan (Table 3).

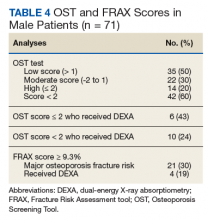

The FRAX and OST scores for each male patient were calculated (Table 4). Half the patients were low risk for osteoporosis. Just 20% (14) of the patients were at high risk for osteoporosis, and only 6 of those had DEXA scans. However, if expanding the criteria to OST scores of < 2, then only 24% (10) received DEXA scans. When calculating FRAX scores, 30% (21) had ≥ 9.3% for major osteoporotic fracture risk, and only 19% (4) had received a DEXA scan.

Discussion

Based on the collected data, many of the male HBPC patients have not had an evaluation for osteoporosis despite being in a high-risk population and meeting some of the screening guidelines by various organizations.1 Based on Diem and colleagues and the 2007 VA report, utilizing OST scores could help capture a subset of patients that would be referred for DEXA scans.5,12 Of the 60% (42) of patients that met OST scores of < 2, 76% (32) of them could have been referred for DEXA scans for osteoporosis evaluation. However, at the time of publication of this article, 50% (16) of the patients have been discharged from the service without interventions. Of the remaining 16 patients, only 2 were referred for a DEXA scan, and 1 patient had confirmed osteoporosis. Currently, these results have been reviewed by the HBPC provider, and plans are in place for DEXA scan referrals for the remaining patients. In addition, for new patients admitted to the program and during annual reviews, the plan is to use OST scores to help screen for osteoporosis.

Limitations

The HBPC population is often in flux due to discharges as patients pass away, become eligible for long-term care, advance to hospice or palliative care status, or see an improvement in their condition to transition back into the community. Along with patients who are bed-bound, have poor prognosis, and barriers to access (eg, transportation issues), interventions for DEXA scan referrals are often not clinically indicated. During calculations of the FRAX score, documentation is often missing from a patient’s medical chart, making it difficult to answer all questions on the questionnaire. This does increase the utility of the OST score as the calculation is much easier and does not rely on other osteoporotic factors. Despite these restrictions for offering DEXA scans, the HBPC service has a high standard of excellence in preventing falls, a major contributor to fractures. Physical therapy services are readily available, nursing visits are frequent and as clinically indicated, vitamin D levels are maintained within normal limits via supplementation, and medication management is performed at least quarterly among other interventions.

Conclusions

The retrospective chart review of patients in the HBPC program suggests that there may be a lack of standardized screening for osteoporosis in the male patient population. As seen within the data, there is great potential for interventions as many of the patients would be candidates for screening based on the OST score. The tool is easy to use and readily accessible to all health care providers and staff. By increasing screening of eligible patients, it also increases the identification of those who would benefit from osteoporosis treatment. While the HBPC population has access limitations (eg, homebound, limited life expectancy), the implementation of a protocol and extension of concepts from this study can be extrapolated into other PACT clinics at VA facilities. Osteoporosis in the male population is often overlooked, but screening procedures can help reduce health care expenditures.

1. Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al; Endocrine Society. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802-1822.

2. Holt G, Smith R, Duncan K, Hutchison JD, Gregori A. Gender differences in epidemiology and outcome after hip fracture: evidence from the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):480-483.

3. Ackman JM, Lata PF, Schuna AA, Elliott ME. Bone health evaluation in a veteran population: a need for the Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX). Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(10):1288-1293.

4. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis in men: why change needs to happen. http://share.iofbone-health.org/WOD/2014/thematic-report/WOD14-Report.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed September 16, 2019.

5. Shekell P, Munjas B, Liu H, et al. Screening Men for Osteoporosis: Who & How. Evidence-based Synthesis Program. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2007.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran population. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp. Accessed September 16, 2019.

7. Rao SS, Budhwar N, Ashfaque A. Osteoporosis in men. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):503-508.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521-2531.

9. Viswanathan M, Reddy S, Berkman N, et al. Screening to prevent osteoporotic fractures updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2532-2551.

10. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381.

11. Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield, UK. FRAX Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=9. Accessed September 16, 2019.

12. Diem SJ, Peters KW, Gourlay ML, et al; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research Group. Screening for osteoporosis in older men: operating characteristics of proposed strategies for selecting men for BMD testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1235-1241.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Osteoporosis risk assessment using Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST) and other interventions at rural facilities. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/promise/2017_02_01_OST_Issue%20Brief_v2.pdf. Published February 7, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2019.

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by the loss of bone density.1 Bone is normally porous and is in a state of flux due to changes in regeneration caused by osteoclast or osteoblast activity. However, age and other factors can accelerate loss in bone density and lead to decreased bone strength and an increased risk of fracture. In men, bone mineral density (BMD) can begin to decline as early as age 30 to 40 years. By age 80 years, 25% of total bone mass may be lost.2

Of the 44 million Americans with low BMD or osteoporosis, 20% are men.1 This group accounts for up to 40% of all osteoporotic fractures. About 1 in 4 men aged ≥ 50 years may experience a lifetime fracture. Fractures may lead to chronic pain, disability, increased dependence, and potentially death. These complications cause expenditures upward of $4.1 billion annually in North America alone.3,4 About 80,000 US men will experience a hip fracture each year, one-third of whom will die within that year. This constitutes a mortality rate 2 to 3 times higher than that of women. Osteoporosis often goes undiagnosed and untreated due to a lack of symptoms until a fracture occurs, underlining the potential benefit of preemptive screening.

In 2007, Shekell and colleagues outlined how the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) screened men for osteoporosis.5 At the time, 95% of the VA population was male, though it has since dropped to 91%.6 Shekell and colleagues estimated that about 200,0000 to 400,0000 male veterans had osteoporosis.5 Osteoporotic risk factors deemed specific to veterans were excessive alcohol use, spinal cord injury and lack of weight-bearing exercise, prolonged corticosteroid use, and androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer. Different screening techniques were assessed, and the VA recommended the Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST).5 Many organizations have developed clinical guidance, including who should be screened; however, screening for men remains a controversial area due to a lack of any strong recommendations (Table 1).

Endocrine Society screening guidelines for men are the most specific: testing BMD in men aged ≥ 70 years, or if aged 50 to 69 years with an additional risk factor (eg, low body weight, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic steroid use).1 The Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX) score is often cited as a common screening tool. It is a free online questionnaire that provides a 10-year probability risk of hip or major osteoporotic fracture.11 However, this tool is limited by age, weight, and the assumption that all questions are answered accurately. Some of the information required includes the presence of a number of risk factors, such as alcohol use, glucocorticoids, and medical history of rheumatoid arthritis, among others (Table 2). The OST score, on the other hand, is a calculation that does not take into account other risk factors (Figure 1). This tool categorizes the patient into low, moderate, or high risk for osteoporosis.8

In a study of 4,000 men aged ≥ 70 years,

A 2017 VA Office of Rural Health study examined the utility of OST to screen referred patients aged > 50 years to receive DEXA scans in patient aligned care team (PACT) clinics at 3 different VA locations.13 The study excluded patients who had been screened previously or treated for osteoporosis, were receiving hospice care; 1 site excluded patients aged > 88 years. Two of the sites also reviewed the patient’s medications to screen for agents that may contribute to increased fracture risk. Veterans identified as high risk were referred for education and offered a DEXA scan and treatment. In total, 867 veterans were screened; 19% (168) were deemed high risk, and 6% (53) underwent DEXA scans. The study noted that only 15 patients had reportable DEXA scans and 10 were positive for bone disease.

As there has been documented success in the PACT setting in implementing standardized protocols for screening and treating veterans, it is reasonable to extend the concept into other VA services. The home-based primary care (HBPC) population is especially vulnerable due to the age of patients, limited weight-bearing exercise to improve bone strength, and limited access to DEXA scans due to difficulty traveling outside of the home. Despite these issues, a goal of the HBPC service is to provide continual care for veterans and improve their health so they may return to the community setting. As a result, patients are followed frequently, providing many opportunities for interventions. This study aims to determine the proportion of HBPC patients who are at high risk for osteoporosis and can receive a DEXA scan for evaluation.

Methods

This study was a retrospective chart analysis using descriptive statistics. It was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center (FHCC). Patients were included in the study if they were enrolled in the HBPC program at FHCC. Patients were excluded if they were receiving hospice or palliative care, had a limited life expectancy per the HBPC provider, or had a diagnosis of osteoporosis that was being managed by a VA endocrinologist, rheumatologist, or non-VA provider.

The study was conducted from February 1, 2018, through November 30, 2018. All chart reviews were done through the FHCC electronic health record. A minimum of 80 and maximum of 150 charts were reviewed as this was the typical patient volume in the HBPC program. Basic demographic information was collected and analyzed by calculating FRAX and OST scores. With the results, patients were classified as low or high risk of developing osteoporosis, and whether a DEXA scan should be recommended.

Results

After chart review, 83 patients were enrolled in the FHCC HBPC program during the study period. Out of these, 5 patients were excluded due to hospice or palliative care status, limited life expectancy, or had their osteoporosis managed by another non-HBPC provider. As a result, 78 patients were analyzed to determine their risk of osteoporosis (Figure 2). Most of the patients were white males with a median age of 82 years. A majority of the patients did not have any current or previous treatment with bisphosphonates, 77% had normal vitamin D levels, and only 13% (10) were current smokers; of the male patients only 21% (15) had a previous DEXA scan (Table 3).

The FRAX and OST scores for each male patient were calculated (Table 4). Half the patients were low risk for osteoporosis. Just 20% (14) of the patients were at high risk for osteoporosis, and only 6 of those had DEXA scans. However, if expanding the criteria to OST scores of < 2, then only 24% (10) received DEXA scans. When calculating FRAX scores, 30% (21) had ≥ 9.3% for major osteoporotic fracture risk, and only 19% (4) had received a DEXA scan.

Discussion

Based on the collected data, many of the male HBPC patients have not had an evaluation for osteoporosis despite being in a high-risk population and meeting some of the screening guidelines by various organizations.1 Based on Diem and colleagues and the 2007 VA report, utilizing OST scores could help capture a subset of patients that would be referred for DEXA scans.5,12 Of the 60% (42) of patients that met OST scores of < 2, 76% (32) of them could have been referred for DEXA scans for osteoporosis evaluation. However, at the time of publication of this article, 50% (16) of the patients have been discharged from the service without interventions. Of the remaining 16 patients, only 2 were referred for a DEXA scan, and 1 patient had confirmed osteoporosis. Currently, these results have been reviewed by the HBPC provider, and plans are in place for DEXA scan referrals for the remaining patients. In addition, for new patients admitted to the program and during annual reviews, the plan is to use OST scores to help screen for osteoporosis.

Limitations

The HBPC population is often in flux due to discharges as patients pass away, become eligible for long-term care, advance to hospice or palliative care status, or see an improvement in their condition to transition back into the community. Along with patients who are bed-bound, have poor prognosis, and barriers to access (eg, transportation issues), interventions for DEXA scan referrals are often not clinically indicated. During calculations of the FRAX score, documentation is often missing from a patient’s medical chart, making it difficult to answer all questions on the questionnaire. This does increase the utility of the OST score as the calculation is much easier and does not rely on other osteoporotic factors. Despite these restrictions for offering DEXA scans, the HBPC service has a high standard of excellence in preventing falls, a major contributor to fractures. Physical therapy services are readily available, nursing visits are frequent and as clinically indicated, vitamin D levels are maintained within normal limits via supplementation, and medication management is performed at least quarterly among other interventions.

Conclusions

The retrospective chart review of patients in the HBPC program suggests that there may be a lack of standardized screening for osteoporosis in the male patient population. As seen within the data, there is great potential for interventions as many of the patients would be candidates for screening based on the OST score. The tool is easy to use and readily accessible to all health care providers and staff. By increasing screening of eligible patients, it also increases the identification of those who would benefit from osteoporosis treatment. While the HBPC population has access limitations (eg, homebound, limited life expectancy), the implementation of a protocol and extension of concepts from this study can be extrapolated into other PACT clinics at VA facilities. Osteoporosis in the male population is often overlooked, but screening procedures can help reduce health care expenditures.

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by the loss of bone density.1 Bone is normally porous and is in a state of flux due to changes in regeneration caused by osteoclast or osteoblast activity. However, age and other factors can accelerate loss in bone density and lead to decreased bone strength and an increased risk of fracture. In men, bone mineral density (BMD) can begin to decline as early as age 30 to 40 years. By age 80 years, 25% of total bone mass may be lost.2

Of the 44 million Americans with low BMD or osteoporosis, 20% are men.1 This group accounts for up to 40% of all osteoporotic fractures. About 1 in 4 men aged ≥ 50 years may experience a lifetime fracture. Fractures may lead to chronic pain, disability, increased dependence, and potentially death. These complications cause expenditures upward of $4.1 billion annually in North America alone.3,4 About 80,000 US men will experience a hip fracture each year, one-third of whom will die within that year. This constitutes a mortality rate 2 to 3 times higher than that of women. Osteoporosis often goes undiagnosed and untreated due to a lack of symptoms until a fracture occurs, underlining the potential benefit of preemptive screening.

In 2007, Shekell and colleagues outlined how the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) screened men for osteoporosis.5 At the time, 95% of the VA population was male, though it has since dropped to 91%.6 Shekell and colleagues estimated that about 200,0000 to 400,0000 male veterans had osteoporosis.5 Osteoporotic risk factors deemed specific to veterans were excessive alcohol use, spinal cord injury and lack of weight-bearing exercise, prolonged corticosteroid use, and androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer. Different screening techniques were assessed, and the VA recommended the Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST).5 Many organizations have developed clinical guidance, including who should be screened; however, screening for men remains a controversial area due to a lack of any strong recommendations (Table 1).

Endocrine Society screening guidelines for men are the most specific: testing BMD in men aged ≥ 70 years, or if aged 50 to 69 years with an additional risk factor (eg, low body weight, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic steroid use).1 The Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX) score is often cited as a common screening tool. It is a free online questionnaire that provides a 10-year probability risk of hip or major osteoporotic fracture.11 However, this tool is limited by age, weight, and the assumption that all questions are answered accurately. Some of the information required includes the presence of a number of risk factors, such as alcohol use, glucocorticoids, and medical history of rheumatoid arthritis, among others (Table 2). The OST score, on the other hand, is a calculation that does not take into account other risk factors (Figure 1). This tool categorizes the patient into low, moderate, or high risk for osteoporosis.8

In a study of 4,000 men aged ≥ 70 years,

A 2017 VA Office of Rural Health study examined the utility of OST to screen referred patients aged > 50 years to receive DEXA scans in patient aligned care team (PACT) clinics at 3 different VA locations.13 The study excluded patients who had been screened previously or treated for osteoporosis, were receiving hospice care; 1 site excluded patients aged > 88 years. Two of the sites also reviewed the patient’s medications to screen for agents that may contribute to increased fracture risk. Veterans identified as high risk were referred for education and offered a DEXA scan and treatment. In total, 867 veterans were screened; 19% (168) were deemed high risk, and 6% (53) underwent DEXA scans. The study noted that only 15 patients had reportable DEXA scans and 10 were positive for bone disease.

As there has been documented success in the PACT setting in implementing standardized protocols for screening and treating veterans, it is reasonable to extend the concept into other VA services. The home-based primary care (HBPC) population is especially vulnerable due to the age of patients, limited weight-bearing exercise to improve bone strength, and limited access to DEXA scans due to difficulty traveling outside of the home. Despite these issues, a goal of the HBPC service is to provide continual care for veterans and improve their health so they may return to the community setting. As a result, patients are followed frequently, providing many opportunities for interventions. This study aims to determine the proportion of HBPC patients who are at high risk for osteoporosis and can receive a DEXA scan for evaluation.

Methods

This study was a retrospective chart analysis using descriptive statistics. It was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center (FHCC). Patients were included in the study if they were enrolled in the HBPC program at FHCC. Patients were excluded if they were receiving hospice or palliative care, had a limited life expectancy per the HBPC provider, or had a diagnosis of osteoporosis that was being managed by a VA endocrinologist, rheumatologist, or non-VA provider.

The study was conducted from February 1, 2018, through November 30, 2018. All chart reviews were done through the FHCC electronic health record. A minimum of 80 and maximum of 150 charts were reviewed as this was the typical patient volume in the HBPC program. Basic demographic information was collected and analyzed by calculating FRAX and OST scores. With the results, patients were classified as low or high risk of developing osteoporosis, and whether a DEXA scan should be recommended.

Results

After chart review, 83 patients were enrolled in the FHCC HBPC program during the study period. Out of these, 5 patients were excluded due to hospice or palliative care status, limited life expectancy, or had their osteoporosis managed by another non-HBPC provider. As a result, 78 patients were analyzed to determine their risk of osteoporosis (Figure 2). Most of the patients were white males with a median age of 82 years. A majority of the patients did not have any current or previous treatment with bisphosphonates, 77% had normal vitamin D levels, and only 13% (10) were current smokers; of the male patients only 21% (15) had a previous DEXA scan (Table 3).

The FRAX and OST scores for each male patient were calculated (Table 4). Half the patients were low risk for osteoporosis. Just 20% (14) of the patients were at high risk for osteoporosis, and only 6 of those had DEXA scans. However, if expanding the criteria to OST scores of < 2, then only 24% (10) received DEXA scans. When calculating FRAX scores, 30% (21) had ≥ 9.3% for major osteoporotic fracture risk, and only 19% (4) had received a DEXA scan.

Discussion

Based on the collected data, many of the male HBPC patients have not had an evaluation for osteoporosis despite being in a high-risk population and meeting some of the screening guidelines by various organizations.1 Based on Diem and colleagues and the 2007 VA report, utilizing OST scores could help capture a subset of patients that would be referred for DEXA scans.5,12 Of the 60% (42) of patients that met OST scores of < 2, 76% (32) of them could have been referred for DEXA scans for osteoporosis evaluation. However, at the time of publication of this article, 50% (16) of the patients have been discharged from the service without interventions. Of the remaining 16 patients, only 2 were referred for a DEXA scan, and 1 patient had confirmed osteoporosis. Currently, these results have been reviewed by the HBPC provider, and plans are in place for DEXA scan referrals for the remaining patients. In addition, for new patients admitted to the program and during annual reviews, the plan is to use OST scores to help screen for osteoporosis.

Limitations

The HBPC population is often in flux due to discharges as patients pass away, become eligible for long-term care, advance to hospice or palliative care status, or see an improvement in their condition to transition back into the community. Along with patients who are bed-bound, have poor prognosis, and barriers to access (eg, transportation issues), interventions for DEXA scan referrals are often not clinically indicated. During calculations of the FRAX score, documentation is often missing from a patient’s medical chart, making it difficult to answer all questions on the questionnaire. This does increase the utility of the OST score as the calculation is much easier and does not rely on other osteoporotic factors. Despite these restrictions for offering DEXA scans, the HBPC service has a high standard of excellence in preventing falls, a major contributor to fractures. Physical therapy services are readily available, nursing visits are frequent and as clinically indicated, vitamin D levels are maintained within normal limits via supplementation, and medication management is performed at least quarterly among other interventions.

Conclusions

The retrospective chart review of patients in the HBPC program suggests that there may be a lack of standardized screening for osteoporosis in the male patient population. As seen within the data, there is great potential for interventions as many of the patients would be candidates for screening based on the OST score. The tool is easy to use and readily accessible to all health care providers and staff. By increasing screening of eligible patients, it also increases the identification of those who would benefit from osteoporosis treatment. While the HBPC population has access limitations (eg, homebound, limited life expectancy), the implementation of a protocol and extension of concepts from this study can be extrapolated into other PACT clinics at VA facilities. Osteoporosis in the male population is often overlooked, but screening procedures can help reduce health care expenditures.

1. Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al; Endocrine Society. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802-1822.

2. Holt G, Smith R, Duncan K, Hutchison JD, Gregori A. Gender differences in epidemiology and outcome after hip fracture: evidence from the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):480-483.

3. Ackman JM, Lata PF, Schuna AA, Elliott ME. Bone health evaluation in a veteran population: a need for the Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX). Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(10):1288-1293.

4. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis in men: why change needs to happen. http://share.iofbone-health.org/WOD/2014/thematic-report/WOD14-Report.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed September 16, 2019.

5. Shekell P, Munjas B, Liu H, et al. Screening Men for Osteoporosis: Who & How. Evidence-based Synthesis Program. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2007.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran population. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp. Accessed September 16, 2019.

7. Rao SS, Budhwar N, Ashfaque A. Osteoporosis in men. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):503-508.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521-2531.

9. Viswanathan M, Reddy S, Berkman N, et al. Screening to prevent osteoporotic fractures updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2532-2551.

10. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381.

11. Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield, UK. FRAX Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=9. Accessed September 16, 2019.

12. Diem SJ, Peters KW, Gourlay ML, et al; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research Group. Screening for osteoporosis in older men: operating characteristics of proposed strategies for selecting men for BMD testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1235-1241.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Osteoporosis risk assessment using Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST) and other interventions at rural facilities. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/promise/2017_02_01_OST_Issue%20Brief_v2.pdf. Published February 7, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2019.

1. Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al; Endocrine Society. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802-1822.

2. Holt G, Smith R, Duncan K, Hutchison JD, Gregori A. Gender differences in epidemiology and outcome after hip fracture: evidence from the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):480-483.

3. Ackman JM, Lata PF, Schuna AA, Elliott ME. Bone health evaluation in a veteran population: a need for the Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX). Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(10):1288-1293.

4. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis in men: why change needs to happen. http://share.iofbone-health.org/WOD/2014/thematic-report/WOD14-Report.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed September 16, 2019.

5. Shekell P, Munjas B, Liu H, et al. Screening Men for Osteoporosis: Who & How. Evidence-based Synthesis Program. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2007.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran population. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp. Accessed September 16, 2019.

7. Rao SS, Budhwar N, Ashfaque A. Osteoporosis in men. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):503-508.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521-2531.

9. Viswanathan M, Reddy S, Berkman N, et al. Screening to prevent osteoporotic fractures updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2532-2551.

10. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381.

11. Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield, UK. FRAX Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=9. Accessed September 16, 2019.

12. Diem SJ, Peters KW, Gourlay ML, et al; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research Group. Screening for osteoporosis in older men: operating characteristics of proposed strategies for selecting men for BMD testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1235-1241.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Osteoporosis risk assessment using Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST) and other interventions at rural facilities. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/promise/2017_02_01_OST_Issue%20Brief_v2.pdf. Published February 7, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2019.