User login

The current increase in measles cases in the United States has sharpened the focus on antivaccine activities. While the percentage of US children who are fully vaccinated remains high (≥ 94%), the number of un- or undervaccinated children has been growing1 because of nonmedical exemptions from school vaccine requirements due to concerns about vaccine safety and an underappreciation of the benefits of vaccines. Family physicians need to be conversant with several important aspects of this matter, including the magnitude of benefits provided by childhood vaccines, as well as the systems already in place for

- assessing vaccine effectiveness and safety,

- making recommendations on the use of vaccines,

- monitoring safety after vaccine approval, and

- compensating those affected by rare but serious vaccine-related adverse events (AEs).

Familiarity with these issues will allow for informed discussions with parents who are vaccine hesitant and with those who have read or heard inaccurate information.

The benefits of vaccines are indisputable

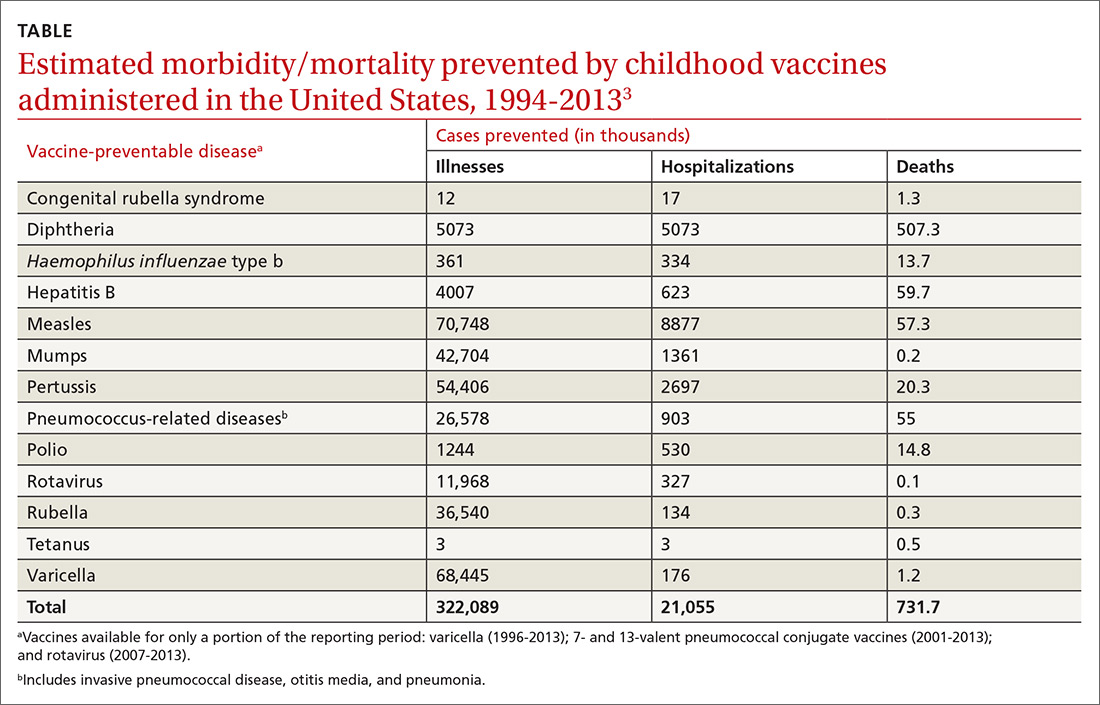

In 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a list of 9 selected childhood infectious diseases and compared their incidences before and after immunization was available.2 Each of these infections causes morbidity, sequelae, and mortality at predictable rates depending on the infectious agent. The comparisons were dramatic: Measles, with a baseline annual morbidity of 503,282 cases, fell to just 89 cases; poliomyelitis decreased from 16,316 to 0; and Haemophilus influenzae type b declined from 20,000 to 54. In a 2014 analysis, the CDC stated that “among 78.6 million children born during 1994–2013, routine childhood immunization was estimated to prevent 322 million illnesses (averaging 4.1 illnesses per child) and 21 million hospitalizations (0.27 per child) over the course of their lifetimes and avert 732,000 premature deaths from vaccine-preventable illnesses” (TABLE).3

It is not unusual to hear a vaccine opponent say that childhood infectious diseases are not serious and that it is better for a child to contract the infection and let the immune system fight it naturally. Measles is often used as an example. This argument ignores some important aspects of vaccine benefits.

It is true in the United States that the average child who contracts measles will recover from it and not suffer immediate or long-term effects. However, it is also true that measles has a hospitalization rate of about 20% and a death rate of between 1/500 and 1/1000 cases.4 Mortality is much higher in developing countries. Prior to widespread use of measles vaccine, hundreds of thousands of cases of measles occurred each year. That translated into hundreds of preventable child deaths per year. An individual case does not tell the full story about the public health impact of infectious illnesses.

In addition, there are often unappreciated sequelae from child infections, such as shingles occurring years after resolution of a chickenpox infection. There are also societal consequences of child infections, such as deafness from congenital rubella and intergenerational transfer of infectious agents to family members at risk for serious consequences (influenza from a child to a grandparent). Finally, infected children pose a risk to those who cannot be vaccinated because of immune deficiencies and other medical conditions.

A multilayered US system monitors vaccine safety

Responsibility for assuring the safety of vaccines lies with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research and with the CDC’s Immunization Safety Office (ISO). The FDA is responsible for the initial assessment of the effectiveness and safety of new vaccines and for ongoing monitoring of the manufacturing facilities where vaccines are produced. After FDA approval, safety is monitored using a multilayered system that includes the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) system, the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Project, and periodic reviews by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), previously the Institute of Medicine. In addition, there is a large number of studies published each year by the nation’s—and world’s—medical research community on vaccine effectiveness and safety.

Continue to: VAERS

VAERS (https://vaers.hhs.gov/) is a passive reporting system that allows patients, physicians, and other health care providers to record suspected vaccine-related adverse events.5 It was created in 1990 and is run by the FDA and the CDC. It is not intended to be a comprehensive or definitive list of proven vaccine-related harms. As a passive reporting system, it is subject to both over- and underreporting, and the data from it are often misinterpreted and used incorrectly by vaccine opponents—eg, wrongly declaring that VAERS reports of possible AEs are proven cases. It provides a sentinel system that is monitored for indications of possible serious AEs linked to a particular vaccine. When a suspected interaction is detected, it is investigated by the VSD system.

VSD is a collaboration of the CDC’s ISO and 8 geographically distributed health care organizations with complete electronic patient medical information on their members. VSD conducts studies when a question about vaccine safety arises, when new vaccines are licensed, or when there are new vaccine recommendations. A description of VSD sites, the research methods used, and a list of publications describing study results can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/vsd/index.html#organizations. If the VSD system finds a link between serious AEs and a particular vaccine, this association is reported to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for consideration in changing recommendations regarding that vaccine. This happens only rarely.

CISA was established in 2001 as a network of vaccine safety experts at 7 academic medical centers who collaborate with the CDC’s ISO. CISA conducts studies on specific questions related to vaccine safety and provides a consultation service to clinicians and researchers who have questions about vaccine safety. A description of the CISA sites, past publications on vaccine safety, and ongoing research priorities can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/cisa/index.html.

NAM (https://nam.edu/) conducts periodic reviews of vaccine safety and vaccine-caused AEs. The most recent was published in 2012 and looked at possible AEs of 8 vaccines containing 12 different antigens.6 The literature search for this review found more than 12,000 articles, which speaks to the volume of scientific work on vaccine safety. These NAM reports document the rarity of severe AEs to vaccines and are used with other information to construct the table for the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), which is described below.

Are vaccines killing children?

Vaccine opponents frequently claim that vaccines cause much more harm than is documented, including the deaths of children. A vaccine opponent made this claim in my state (Arizona) at a legislative committee hearing even though our state child mortality review committee has been investigating all child deaths for decades and has never attributed a death to a vaccine.

Continue to: One study conducted...

One study conducted using the VSD system from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2011, identified 1100 deaths occurring within 12 months of any vaccination among 2,189,504 VSD enrollees ages 9 to 26 years.7 They found that the risk of death in this age group was not increased during the 30 days after vaccination, and no deaths were found to be causally associated with vaccination. Deaths among children do occur and, due to the number of vaccines administered, some deaths will occur within a short time period after a vaccine. This temporal association does not prove the death was vaccine-caused, but vaccine opponents have claimed that it does.

The vaccine injury compensation system

In 1986, the federal government established a no-fault system—the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP)—to compensate those who suffer a serious AE from a vaccine covered by the program. This system is administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) in the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). HRSA maintains a table of proven AEs of specific vaccines, based in part on the NAM report mentioned earlier. Petitions for compensation—with proof of an AE following the administration of a vaccine that is included on the HRSA table—are accepted and remunerated if the AE lasted > 6 months or resulted in hospitalization. Petitions that allege AEs following administration of a vaccine not included on the table are nevertheless reviewed by the staff of HRSA, who can still recommend compensation based on the medical evidence. If HRSA declines the petition, the petitioner can appeal the case in the US Court of Federal Claims, which makes the final decision on a petition’s validity and, if warranted, the type and amount of compensation.

From 2006 to 2017, > 3.4 billion doses of vaccines covered by VICP were distributed in the United States.8 During this period, 6293 petitions were adjudicated by the court; 4311 were compensated.8 For every 1 million doses of vaccine distributed, 1 individual was compensated. Seventy percent of these compensations were awarded to petitioners despite a lack of clear evidence that the patient’s condition was caused by a vaccine.8 The rate of compensation for conditions proven to be caused by a vaccine was 1/3.33 million.8

The VICP pays for attorney fees, in some cases even if the petition is denied, but does not allow contingency fees. Since the beginning of the program, more than $4 billion has been awarded.8 The program is funded by a 75-cent tax on each vaccine antigen. Because serious AEs are so rare, the trust fund established to administer the VICP finances has a surplus of about $6 billion.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

After a vaccine is approved for use by the FDA, ACIP makes recommendations for its use in the US civilian population.9,10 ACIP, created in 1964, was chartered as a federal advisory committee to provide expert external advice to the Director of the CDC and the Secretary of DHHS on the use of vaccines

Continue to: As an official...

As an official federal advisory committee governed by the Federal Advisory Committee Act, ACIP operates under strict requirements for public notification of meetings, allowing for written and oral public comment at its meetings, and timely publication of minutes. ACIP meeting minutes are posted soon after each meeting, along with draft recommendations. ACIP meeting agendas and slide presentations are available on the ACIP Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/index.html).

ACIP consists of 15 members serving overlapping 4-year terms, appointed by the Secretary of DHHS from a list of candidates proposed by the CDC. One member is a consumer representative; the other members have expertise in vaccinology, immunology, pediatrics, internal medicine, infectious diseases, preventive medicine, and public health. In the CDC, staff support for ACIP is provided by the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Office of Infectious Diseases.

ACIP holds 2-day meetings 3 times a year. Much of the work occurs between meetings, by work groups via phone conferences. Work groups are chaired by an ACIP member and staffed by one or more CDC programmatic, content-expert professionals. Membership of the work groups consists of at least 2 ACIP members, representatives from relevant professional clinical and public health organizations, and other individuals with specific expertise. Work groups propose recommendations to ACIP, which can adopt, revise, or reject them.

When formulating recommendations for a particular vaccine, ACIP considers the burden of disease prevented, the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine, cost effectiveness, and practical and logistical issues of implementing recommendations. ACIP also receives frequent reports from ISO regarding the safety of vaccines previously approved. Since 2011, ACIP has used a standardized, modified GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) system to assess the evidence regarding effectiveness and safety of new vaccines and an evidence-to-recommendation framework to transparently explain how it arrives at recommendations.11,12

We can recommend vaccines with confidence

In the United States, we have a secure supply of safe vaccines, a transparent method of making vaccine recommendations, a robust system to monitor vaccine safety, and an efficient system to compensate those who experience a rare, serious adverse reaction to a vaccine. The US public health system has achieved a marked reduction in morbidity and mortality from childhood infectious diseases, mostly because of vaccines. Many people today have not experienced or seen children with these once-common childhood infections and may not appreciate the seriousness of childhood infectious diseases or the full value of vaccines. As family physicians, we can help address this problem and recommend vaccines to our patients with confidence.

1. Mellerson JL, Maxwell CB, Knighton CL, et al. Vaccine coverage for selected vaccines and exemption rates among children in kindergarten—United States, 2017-18 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1115-1122.

2. CDC. Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:241-243.

3. Whitney CG, Zhou F, Singleton J, et al. Benefits from immunization during the Vaccines for Children Program era—United States, 1994-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:352-355.

4. CDC. Complications of measles. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/symptoms/complications.html. Accessed July 16, 2019.

5. Shimabukuro TT, Nguyen M, Martin D, et al. Safety monitoring in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). Vaccine. 2015;33:4398-4405.

6. IOM (Institute of Medicine). Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012.

7. McCarthy NL, Gee J, Sukumaran L, et al. Vaccination and 30-day mortality risk in children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatrics. 2016;137:1-8.

8. HRSA. Data and Statistics. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/vaccine-compensation/data/monthly-stats-may-2019.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2019.

9. Pickering LK, Orenstein WA, Sun W, et al. FDA licensure of and ACIP recommendations for vaccines. Vaccine. 2017;37:5027-5036.

10. Smith JC, Snider DE, Pickering LK. Immunization policy development in the United States: the role of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:45-49.

11. Ahmed F, Temte JL, Campos-Outcalt D, et al; for the ACIP Evidence Based Recommendations Work Group (EBRWG). Methods for developing evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine. 2011;29:9171-9176.

12. Lee G, Carr W. Updated framework for development of evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018:76:1271-1272.

The current increase in measles cases in the United States has sharpened the focus on antivaccine activities. While the percentage of US children who are fully vaccinated remains high (≥ 94%), the number of un- or undervaccinated children has been growing1 because of nonmedical exemptions from school vaccine requirements due to concerns about vaccine safety and an underappreciation of the benefits of vaccines. Family physicians need to be conversant with several important aspects of this matter, including the magnitude of benefits provided by childhood vaccines, as well as the systems already in place for

- assessing vaccine effectiveness and safety,

- making recommendations on the use of vaccines,

- monitoring safety after vaccine approval, and

- compensating those affected by rare but serious vaccine-related adverse events (AEs).

Familiarity with these issues will allow for informed discussions with parents who are vaccine hesitant and with those who have read or heard inaccurate information.

The benefits of vaccines are indisputable

In 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a list of 9 selected childhood infectious diseases and compared their incidences before and after immunization was available.2 Each of these infections causes morbidity, sequelae, and mortality at predictable rates depending on the infectious agent. The comparisons were dramatic: Measles, with a baseline annual morbidity of 503,282 cases, fell to just 89 cases; poliomyelitis decreased from 16,316 to 0; and Haemophilus influenzae type b declined from 20,000 to 54. In a 2014 analysis, the CDC stated that “among 78.6 million children born during 1994–2013, routine childhood immunization was estimated to prevent 322 million illnesses (averaging 4.1 illnesses per child) and 21 million hospitalizations (0.27 per child) over the course of their lifetimes and avert 732,000 premature deaths from vaccine-preventable illnesses” (TABLE).3

It is not unusual to hear a vaccine opponent say that childhood infectious diseases are not serious and that it is better for a child to contract the infection and let the immune system fight it naturally. Measles is often used as an example. This argument ignores some important aspects of vaccine benefits.

It is true in the United States that the average child who contracts measles will recover from it and not suffer immediate or long-term effects. However, it is also true that measles has a hospitalization rate of about 20% and a death rate of between 1/500 and 1/1000 cases.4 Mortality is much higher in developing countries. Prior to widespread use of measles vaccine, hundreds of thousands of cases of measles occurred each year. That translated into hundreds of preventable child deaths per year. An individual case does not tell the full story about the public health impact of infectious illnesses.

In addition, there are often unappreciated sequelae from child infections, such as shingles occurring years after resolution of a chickenpox infection. There are also societal consequences of child infections, such as deafness from congenital rubella and intergenerational transfer of infectious agents to family members at risk for serious consequences (influenza from a child to a grandparent). Finally, infected children pose a risk to those who cannot be vaccinated because of immune deficiencies and other medical conditions.

A multilayered US system monitors vaccine safety

Responsibility for assuring the safety of vaccines lies with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research and with the CDC’s Immunization Safety Office (ISO). The FDA is responsible for the initial assessment of the effectiveness and safety of new vaccines and for ongoing monitoring of the manufacturing facilities where vaccines are produced. After FDA approval, safety is monitored using a multilayered system that includes the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) system, the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Project, and periodic reviews by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), previously the Institute of Medicine. In addition, there is a large number of studies published each year by the nation’s—and world’s—medical research community on vaccine effectiveness and safety.

Continue to: VAERS

VAERS (https://vaers.hhs.gov/) is a passive reporting system that allows patients, physicians, and other health care providers to record suspected vaccine-related adverse events.5 It was created in 1990 and is run by the FDA and the CDC. It is not intended to be a comprehensive or definitive list of proven vaccine-related harms. As a passive reporting system, it is subject to both over- and underreporting, and the data from it are often misinterpreted and used incorrectly by vaccine opponents—eg, wrongly declaring that VAERS reports of possible AEs are proven cases. It provides a sentinel system that is monitored for indications of possible serious AEs linked to a particular vaccine. When a suspected interaction is detected, it is investigated by the VSD system.

VSD is a collaboration of the CDC’s ISO and 8 geographically distributed health care organizations with complete electronic patient medical information on their members. VSD conducts studies when a question about vaccine safety arises, when new vaccines are licensed, or when there are new vaccine recommendations. A description of VSD sites, the research methods used, and a list of publications describing study results can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/vsd/index.html#organizations. If the VSD system finds a link between serious AEs and a particular vaccine, this association is reported to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for consideration in changing recommendations regarding that vaccine. This happens only rarely.

CISA was established in 2001 as a network of vaccine safety experts at 7 academic medical centers who collaborate with the CDC’s ISO. CISA conducts studies on specific questions related to vaccine safety and provides a consultation service to clinicians and researchers who have questions about vaccine safety. A description of the CISA sites, past publications on vaccine safety, and ongoing research priorities can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/cisa/index.html.

NAM (https://nam.edu/) conducts periodic reviews of vaccine safety and vaccine-caused AEs. The most recent was published in 2012 and looked at possible AEs of 8 vaccines containing 12 different antigens.6 The literature search for this review found more than 12,000 articles, which speaks to the volume of scientific work on vaccine safety. These NAM reports document the rarity of severe AEs to vaccines and are used with other information to construct the table for the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), which is described below.

Are vaccines killing children?

Vaccine opponents frequently claim that vaccines cause much more harm than is documented, including the deaths of children. A vaccine opponent made this claim in my state (Arizona) at a legislative committee hearing even though our state child mortality review committee has been investigating all child deaths for decades and has never attributed a death to a vaccine.

Continue to: One study conducted...

One study conducted using the VSD system from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2011, identified 1100 deaths occurring within 12 months of any vaccination among 2,189,504 VSD enrollees ages 9 to 26 years.7 They found that the risk of death in this age group was not increased during the 30 days after vaccination, and no deaths were found to be causally associated with vaccination. Deaths among children do occur and, due to the number of vaccines administered, some deaths will occur within a short time period after a vaccine. This temporal association does not prove the death was vaccine-caused, but vaccine opponents have claimed that it does.

The vaccine injury compensation system

In 1986, the federal government established a no-fault system—the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP)—to compensate those who suffer a serious AE from a vaccine covered by the program. This system is administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) in the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). HRSA maintains a table of proven AEs of specific vaccines, based in part on the NAM report mentioned earlier. Petitions for compensation—with proof of an AE following the administration of a vaccine that is included on the HRSA table—are accepted and remunerated if the AE lasted > 6 months or resulted in hospitalization. Petitions that allege AEs following administration of a vaccine not included on the table are nevertheless reviewed by the staff of HRSA, who can still recommend compensation based on the medical evidence. If HRSA declines the petition, the petitioner can appeal the case in the US Court of Federal Claims, which makes the final decision on a petition’s validity and, if warranted, the type and amount of compensation.

From 2006 to 2017, > 3.4 billion doses of vaccines covered by VICP were distributed in the United States.8 During this period, 6293 petitions were adjudicated by the court; 4311 were compensated.8 For every 1 million doses of vaccine distributed, 1 individual was compensated. Seventy percent of these compensations were awarded to petitioners despite a lack of clear evidence that the patient’s condition was caused by a vaccine.8 The rate of compensation for conditions proven to be caused by a vaccine was 1/3.33 million.8

The VICP pays for attorney fees, in some cases even if the petition is denied, but does not allow contingency fees. Since the beginning of the program, more than $4 billion has been awarded.8 The program is funded by a 75-cent tax on each vaccine antigen. Because serious AEs are so rare, the trust fund established to administer the VICP finances has a surplus of about $6 billion.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

After a vaccine is approved for use by the FDA, ACIP makes recommendations for its use in the US civilian population.9,10 ACIP, created in 1964, was chartered as a federal advisory committee to provide expert external advice to the Director of the CDC and the Secretary of DHHS on the use of vaccines

Continue to: As an official...

As an official federal advisory committee governed by the Federal Advisory Committee Act, ACIP operates under strict requirements for public notification of meetings, allowing for written and oral public comment at its meetings, and timely publication of minutes. ACIP meeting minutes are posted soon after each meeting, along with draft recommendations. ACIP meeting agendas and slide presentations are available on the ACIP Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/index.html).

ACIP consists of 15 members serving overlapping 4-year terms, appointed by the Secretary of DHHS from a list of candidates proposed by the CDC. One member is a consumer representative; the other members have expertise in vaccinology, immunology, pediatrics, internal medicine, infectious diseases, preventive medicine, and public health. In the CDC, staff support for ACIP is provided by the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Office of Infectious Diseases.

ACIP holds 2-day meetings 3 times a year. Much of the work occurs between meetings, by work groups via phone conferences. Work groups are chaired by an ACIP member and staffed by one or more CDC programmatic, content-expert professionals. Membership of the work groups consists of at least 2 ACIP members, representatives from relevant professional clinical and public health organizations, and other individuals with specific expertise. Work groups propose recommendations to ACIP, which can adopt, revise, or reject them.

When formulating recommendations for a particular vaccine, ACIP considers the burden of disease prevented, the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine, cost effectiveness, and practical and logistical issues of implementing recommendations. ACIP also receives frequent reports from ISO regarding the safety of vaccines previously approved. Since 2011, ACIP has used a standardized, modified GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) system to assess the evidence regarding effectiveness and safety of new vaccines and an evidence-to-recommendation framework to transparently explain how it arrives at recommendations.11,12

We can recommend vaccines with confidence

In the United States, we have a secure supply of safe vaccines, a transparent method of making vaccine recommendations, a robust system to monitor vaccine safety, and an efficient system to compensate those who experience a rare, serious adverse reaction to a vaccine. The US public health system has achieved a marked reduction in morbidity and mortality from childhood infectious diseases, mostly because of vaccines. Many people today have not experienced or seen children with these once-common childhood infections and may not appreciate the seriousness of childhood infectious diseases or the full value of vaccines. As family physicians, we can help address this problem and recommend vaccines to our patients with confidence.

The current increase in measles cases in the United States has sharpened the focus on antivaccine activities. While the percentage of US children who are fully vaccinated remains high (≥ 94%), the number of un- or undervaccinated children has been growing1 because of nonmedical exemptions from school vaccine requirements due to concerns about vaccine safety and an underappreciation of the benefits of vaccines. Family physicians need to be conversant with several important aspects of this matter, including the magnitude of benefits provided by childhood vaccines, as well as the systems already in place for

- assessing vaccine effectiveness and safety,

- making recommendations on the use of vaccines,

- monitoring safety after vaccine approval, and

- compensating those affected by rare but serious vaccine-related adverse events (AEs).

Familiarity with these issues will allow for informed discussions with parents who are vaccine hesitant and with those who have read or heard inaccurate information.

The benefits of vaccines are indisputable

In 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a list of 9 selected childhood infectious diseases and compared their incidences before and after immunization was available.2 Each of these infections causes morbidity, sequelae, and mortality at predictable rates depending on the infectious agent. The comparisons were dramatic: Measles, with a baseline annual morbidity of 503,282 cases, fell to just 89 cases; poliomyelitis decreased from 16,316 to 0; and Haemophilus influenzae type b declined from 20,000 to 54. In a 2014 analysis, the CDC stated that “among 78.6 million children born during 1994–2013, routine childhood immunization was estimated to prevent 322 million illnesses (averaging 4.1 illnesses per child) and 21 million hospitalizations (0.27 per child) over the course of their lifetimes and avert 732,000 premature deaths from vaccine-preventable illnesses” (TABLE).3

It is not unusual to hear a vaccine opponent say that childhood infectious diseases are not serious and that it is better for a child to contract the infection and let the immune system fight it naturally. Measles is often used as an example. This argument ignores some important aspects of vaccine benefits.

It is true in the United States that the average child who contracts measles will recover from it and not suffer immediate or long-term effects. However, it is also true that measles has a hospitalization rate of about 20% and a death rate of between 1/500 and 1/1000 cases.4 Mortality is much higher in developing countries. Prior to widespread use of measles vaccine, hundreds of thousands of cases of measles occurred each year. That translated into hundreds of preventable child deaths per year. An individual case does not tell the full story about the public health impact of infectious illnesses.

In addition, there are often unappreciated sequelae from child infections, such as shingles occurring years after resolution of a chickenpox infection. There are also societal consequences of child infections, such as deafness from congenital rubella and intergenerational transfer of infectious agents to family members at risk for serious consequences (influenza from a child to a grandparent). Finally, infected children pose a risk to those who cannot be vaccinated because of immune deficiencies and other medical conditions.

A multilayered US system monitors vaccine safety

Responsibility for assuring the safety of vaccines lies with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research and with the CDC’s Immunization Safety Office (ISO). The FDA is responsible for the initial assessment of the effectiveness and safety of new vaccines and for ongoing monitoring of the manufacturing facilities where vaccines are produced. After FDA approval, safety is monitored using a multilayered system that includes the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) system, the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Project, and periodic reviews by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), previously the Institute of Medicine. In addition, there is a large number of studies published each year by the nation’s—and world’s—medical research community on vaccine effectiveness and safety.

Continue to: VAERS

VAERS (https://vaers.hhs.gov/) is a passive reporting system that allows patients, physicians, and other health care providers to record suspected vaccine-related adverse events.5 It was created in 1990 and is run by the FDA and the CDC. It is not intended to be a comprehensive or definitive list of proven vaccine-related harms. As a passive reporting system, it is subject to both over- and underreporting, and the data from it are often misinterpreted and used incorrectly by vaccine opponents—eg, wrongly declaring that VAERS reports of possible AEs are proven cases. It provides a sentinel system that is monitored for indications of possible serious AEs linked to a particular vaccine. When a suspected interaction is detected, it is investigated by the VSD system.

VSD is a collaboration of the CDC’s ISO and 8 geographically distributed health care organizations with complete electronic patient medical information on their members. VSD conducts studies when a question about vaccine safety arises, when new vaccines are licensed, or when there are new vaccine recommendations. A description of VSD sites, the research methods used, and a list of publications describing study results can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/vsd/index.html#organizations. If the VSD system finds a link between serious AEs and a particular vaccine, this association is reported to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for consideration in changing recommendations regarding that vaccine. This happens only rarely.

CISA was established in 2001 as a network of vaccine safety experts at 7 academic medical centers who collaborate with the CDC’s ISO. CISA conducts studies on specific questions related to vaccine safety and provides a consultation service to clinicians and researchers who have questions about vaccine safety. A description of the CISA sites, past publications on vaccine safety, and ongoing research priorities can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/cisa/index.html.

NAM (https://nam.edu/) conducts periodic reviews of vaccine safety and vaccine-caused AEs. The most recent was published in 2012 and looked at possible AEs of 8 vaccines containing 12 different antigens.6 The literature search for this review found more than 12,000 articles, which speaks to the volume of scientific work on vaccine safety. These NAM reports document the rarity of severe AEs to vaccines and are used with other information to construct the table for the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), which is described below.

Are vaccines killing children?

Vaccine opponents frequently claim that vaccines cause much more harm than is documented, including the deaths of children. A vaccine opponent made this claim in my state (Arizona) at a legislative committee hearing even though our state child mortality review committee has been investigating all child deaths for decades and has never attributed a death to a vaccine.

Continue to: One study conducted...

One study conducted using the VSD system from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2011, identified 1100 deaths occurring within 12 months of any vaccination among 2,189,504 VSD enrollees ages 9 to 26 years.7 They found that the risk of death in this age group was not increased during the 30 days after vaccination, and no deaths were found to be causally associated with vaccination. Deaths among children do occur and, due to the number of vaccines administered, some deaths will occur within a short time period after a vaccine. This temporal association does not prove the death was vaccine-caused, but vaccine opponents have claimed that it does.

The vaccine injury compensation system

In 1986, the federal government established a no-fault system—the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP)—to compensate those who suffer a serious AE from a vaccine covered by the program. This system is administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) in the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). HRSA maintains a table of proven AEs of specific vaccines, based in part on the NAM report mentioned earlier. Petitions for compensation—with proof of an AE following the administration of a vaccine that is included on the HRSA table—are accepted and remunerated if the AE lasted > 6 months or resulted in hospitalization. Petitions that allege AEs following administration of a vaccine not included on the table are nevertheless reviewed by the staff of HRSA, who can still recommend compensation based on the medical evidence. If HRSA declines the petition, the petitioner can appeal the case in the US Court of Federal Claims, which makes the final decision on a petition’s validity and, if warranted, the type and amount of compensation.

From 2006 to 2017, > 3.4 billion doses of vaccines covered by VICP were distributed in the United States.8 During this period, 6293 petitions were adjudicated by the court; 4311 were compensated.8 For every 1 million doses of vaccine distributed, 1 individual was compensated. Seventy percent of these compensations were awarded to petitioners despite a lack of clear evidence that the patient’s condition was caused by a vaccine.8 The rate of compensation for conditions proven to be caused by a vaccine was 1/3.33 million.8

The VICP pays for attorney fees, in some cases even if the petition is denied, but does not allow contingency fees. Since the beginning of the program, more than $4 billion has been awarded.8 The program is funded by a 75-cent tax on each vaccine antigen. Because serious AEs are so rare, the trust fund established to administer the VICP finances has a surplus of about $6 billion.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

After a vaccine is approved for use by the FDA, ACIP makes recommendations for its use in the US civilian population.9,10 ACIP, created in 1964, was chartered as a federal advisory committee to provide expert external advice to the Director of the CDC and the Secretary of DHHS on the use of vaccines

Continue to: As an official...

As an official federal advisory committee governed by the Federal Advisory Committee Act, ACIP operates under strict requirements for public notification of meetings, allowing for written and oral public comment at its meetings, and timely publication of minutes. ACIP meeting minutes are posted soon after each meeting, along with draft recommendations. ACIP meeting agendas and slide presentations are available on the ACIP Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/index.html).

ACIP consists of 15 members serving overlapping 4-year terms, appointed by the Secretary of DHHS from a list of candidates proposed by the CDC. One member is a consumer representative; the other members have expertise in vaccinology, immunology, pediatrics, internal medicine, infectious diseases, preventive medicine, and public health. In the CDC, staff support for ACIP is provided by the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Office of Infectious Diseases.

ACIP holds 2-day meetings 3 times a year. Much of the work occurs between meetings, by work groups via phone conferences. Work groups are chaired by an ACIP member and staffed by one or more CDC programmatic, content-expert professionals. Membership of the work groups consists of at least 2 ACIP members, representatives from relevant professional clinical and public health organizations, and other individuals with specific expertise. Work groups propose recommendations to ACIP, which can adopt, revise, or reject them.

When formulating recommendations for a particular vaccine, ACIP considers the burden of disease prevented, the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine, cost effectiveness, and practical and logistical issues of implementing recommendations. ACIP also receives frequent reports from ISO regarding the safety of vaccines previously approved. Since 2011, ACIP has used a standardized, modified GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) system to assess the evidence regarding effectiveness and safety of new vaccines and an evidence-to-recommendation framework to transparently explain how it arrives at recommendations.11,12

We can recommend vaccines with confidence

In the United States, we have a secure supply of safe vaccines, a transparent method of making vaccine recommendations, a robust system to monitor vaccine safety, and an efficient system to compensate those who experience a rare, serious adverse reaction to a vaccine. The US public health system has achieved a marked reduction in morbidity and mortality from childhood infectious diseases, mostly because of vaccines. Many people today have not experienced or seen children with these once-common childhood infections and may not appreciate the seriousness of childhood infectious diseases or the full value of vaccines. As family physicians, we can help address this problem and recommend vaccines to our patients with confidence.

1. Mellerson JL, Maxwell CB, Knighton CL, et al. Vaccine coverage for selected vaccines and exemption rates among children in kindergarten—United States, 2017-18 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1115-1122.

2. CDC. Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:241-243.

3. Whitney CG, Zhou F, Singleton J, et al. Benefits from immunization during the Vaccines for Children Program era—United States, 1994-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:352-355.

4. CDC. Complications of measles. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/symptoms/complications.html. Accessed July 16, 2019.

5. Shimabukuro TT, Nguyen M, Martin D, et al. Safety monitoring in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). Vaccine. 2015;33:4398-4405.

6. IOM (Institute of Medicine). Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012.

7. McCarthy NL, Gee J, Sukumaran L, et al. Vaccination and 30-day mortality risk in children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatrics. 2016;137:1-8.

8. HRSA. Data and Statistics. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/vaccine-compensation/data/monthly-stats-may-2019.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2019.

9. Pickering LK, Orenstein WA, Sun W, et al. FDA licensure of and ACIP recommendations for vaccines. Vaccine. 2017;37:5027-5036.

10. Smith JC, Snider DE, Pickering LK. Immunization policy development in the United States: the role of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:45-49.

11. Ahmed F, Temte JL, Campos-Outcalt D, et al; for the ACIP Evidence Based Recommendations Work Group (EBRWG). Methods for developing evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine. 2011;29:9171-9176.

12. Lee G, Carr W. Updated framework for development of evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018:76:1271-1272.

1. Mellerson JL, Maxwell CB, Knighton CL, et al. Vaccine coverage for selected vaccines and exemption rates among children in kindergarten—United States, 2017-18 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1115-1122.

2. CDC. Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:241-243.

3. Whitney CG, Zhou F, Singleton J, et al. Benefits from immunization during the Vaccines for Children Program era—United States, 1994-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:352-355.

4. CDC. Complications of measles. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/symptoms/complications.html. Accessed July 16, 2019.

5. Shimabukuro TT, Nguyen M, Martin D, et al. Safety monitoring in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). Vaccine. 2015;33:4398-4405.

6. IOM (Institute of Medicine). Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012.

7. McCarthy NL, Gee J, Sukumaran L, et al. Vaccination and 30-day mortality risk in children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatrics. 2016;137:1-8.

8. HRSA. Data and Statistics. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/vaccine-compensation/data/monthly-stats-may-2019.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2019.

9. Pickering LK, Orenstein WA, Sun W, et al. FDA licensure of and ACIP recommendations for vaccines. Vaccine. 2017;37:5027-5036.

10. Smith JC, Snider DE, Pickering LK. Immunization policy development in the United States: the role of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:45-49.

11. Ahmed F, Temte JL, Campos-Outcalt D, et al; for the ACIP Evidence Based Recommendations Work Group (EBRWG). Methods for developing evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine. 2011;29:9171-9176.

12. Lee G, Carr W. Updated framework for development of evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018:76:1271-1272.