User login

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Conditions associated with increased risk for case disease

- Outcome for the case patient

- Differential diagnosis

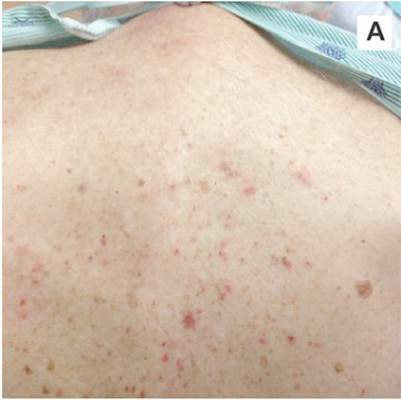

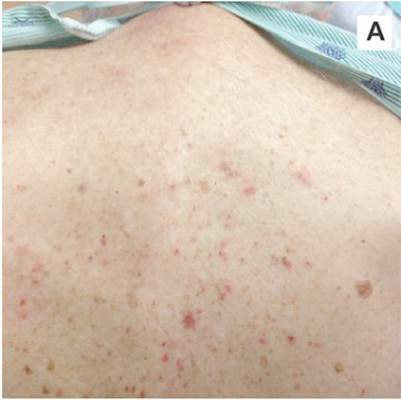

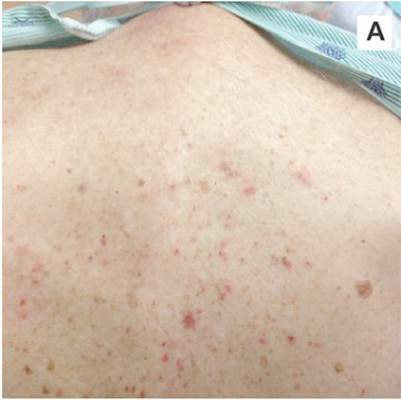

A 78-year-old white man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is admitted to the hospital with worsening cough, shortness of breath, and fever. His medical history is significant for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii in the past year. In the weeks preceding hospital admission, the patient developed an erythematous rash over his trunk (see photographs).

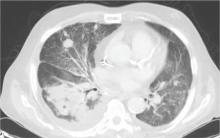

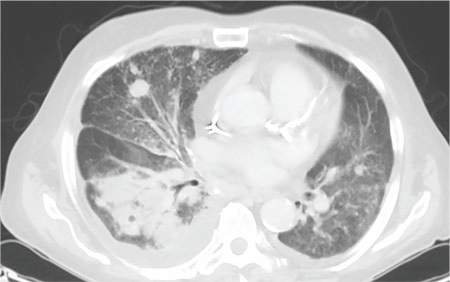

During the man’s hospital stay, this eruption becomes increasingly pruritic and spreads to his proximal extremities. His pulmonary symptoms improve slightly following the initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin), but CT performed one week after admission reveals worsening pulmonary disease (see image). The radiologist’s differential diagnosis includes neoplasm, fungal infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and autoimmune disease.

|  |

| A. The patient's back shows a distribution of lesions, with areas of excoriation caused by scratching. | B. A close-up reveals erythematous papules and keratotic papules. |

Suspecting that the progressive rash is related to the systemic process, the provider orders a punch biopsy in an effort to reach a diagnosis with minimally invasive studies. When the patient’s clinical status further declines, he undergoes video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to obtain an excisional biopsy of one of the pulmonary nodules. Subsequent analysis reveals fungal organisms consistent with histoplasmosis. Interestingly, in the histologic review of the skin biopsy, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis—suggestive of Grover disease—is identified.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Grover disease (GD), also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, is a skin condition of uncertain pathophysiology. Its clinical presentation can be difficult to distinguish from other dermopathies.1,2

Incidence

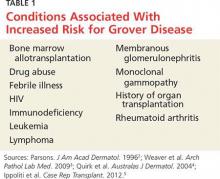

GD most commonly appears in fair-skinned persons of late middle age, with men affected at two to three times the rate seen in women.1,2 Although GD has been documented in patients ranging in age from 4 to 100, this dermopathy is rare in younger patients.1-3 Persons with a prior history of atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, or xerosis cutis are at increased risk for GD—likely due to an increased dermatologic sensitivity to irritants resulting from the aforementioned disorders.1,4 Risk for GD is also elevated in patients with chronic medical conditions, immunodeficiency, febrile illnesses, or malignancies (see Table 1).2-5

The true incidence of GD is not known; biopsy-proven GD is uncommon, and specific data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition are lacking. Swiss researchers who reviewed more than 30,000 skin biopsies in the late 1990s noted only 24 diagnosed cases of GD, and similar findings have been reported in the United States.1,6 However, the variable presentation and often mild nature of GD may result in cases of misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, or empiric treatment in the absence of a formal diagnosis.7

Causative factors

Although the pathophysiology of GD is uncertain, the most likely cause is an occlusion of the eccrine glands.3 This is followed by acantholysis, or separation of keratinocytes within the epidermis, which in turn leads to the development of vesicular lesions.

Though diagnosed most often in the winter, GD has also been associated with exposure to sunlight, heat, xerosis, and diaphoresis.1,3 Hospitalized or bedridden patients are at risk for occlusion of the eccrine glands and thus for GD. Use of certain therapies, including sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (an antimalarial treatment), ionizing radiation, and interleukin-4, may also be precursors for the condition.2

Other exacerbating factors have been suggested, but reports are largely limited to case studies and other anecdotal publications.2 Concrete data regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of GD are still relatively scarce.

Clinical presentation

Patients with GD present with pruritic dermatitis on the trunk and proximal extremities, most classically on the anterior chest and mid back.2,3 The severity of the rash does not necessarily correlate to the degree of pruritus. Some patients report only mild pruritus, while others experience debilitating discomfort and pain. In most cases, erythematous and violaceous papules and vesicles appear first, followed by keratotic erosions.3

GD is a self-limited disorder that often resolves within a few weeks, although some cases will persist for several months.3,5 Severity and duration of symptoms appear to be correlated with increasing age; elderly patients experience worse pruritus for longer periods than do younger patients.2

Although the condition is sometimes referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis, there are three typical presentations of GD: transient eruptive, persistent pruritic, and chronic asymptomatic.4 Transient eruptive GD presents suddenly, with intense pruritus, and tends to subside over several weeks. Persistent pruritic disease generally causes a milder pruritus, with symptoms that last for several months and are not well controlled by medication. Chronic asymptomatic GD can be difficult to treat medically, yet this form of the disease typically causes little to no irritation and requires minimal therapeutic intervention.4

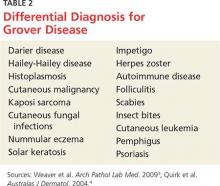

Systemic symptoms of GD have not been observed. Pruritus and rash are the main features in most affected patients. However, pruritic papulovesicular eruptions are commonly seen in other conditions with similar characteristics (see Table 2,3,4), and GD is comparatively rare. While clinical appearance alone may suggest a diagnosis of GD, further testing may be needed to eliminate other conditions from the differential.

Treatment and prognosis

In the absence of randomized therapeutic trials for GD, there are no strict guidelines for treatment. When irritation, inflammation, and pruritus become bothersome, several interventions may be considered. The first step may consist of efforts to modify aggravating factors, such as dry skin, occlusion, excess heat, and rapid temperature changes. Indeed, for mild cases of GD, this may be all that is required.

The firstline pharmacotherapy for GD is medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroids, which reduce inflammation and pruritus in approximately half of affected patients.3,6,8 Topical emollients and oral antihistamines can also provide symptom relief. Vitamin D analogues are considered secondline therapy, and retinoids (both topical and systemic) have also been shown to reduce GD severity.3,4,8

Severe, refractory cases may require more aggressive systemic therapy with corticosteroids or retinoids. For pruritic relief, several weeks of oral corticosteroids may be necessary—and GD may rebound after treatment ceases.3,4 Therefore, oral corticosteroids should only be considered for severe or persistent cases, since the systemic adverse effects (eg, immunosuppression, weight gain, dysglycemia) of these drugs may outweigh the benefits in patients with GD. Other interventions, including phototherapy and immunosuppressive drugs (eg, etanercept) have also demonstrated benefit in select patients.4,9,10

The self-limited nature of GD, along with its lack of systemic symptoms, is associated with a generally benign course of disease and no long-term sequelae.3,5

Continue to outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

This case involved an immunocompromised patient with systemic symptoms, vasculitic cutaneous lesions, and significant pulmonary disease. The differential diagnosis was extensive, and diagnosis based on clinical grounds alone was extremely challenging. In these circumstances, diagnostic testing was essential to reach a final diagnosis.

In this case, the skin biopsy yielded a diagnosis of GD, and the rash was found to be unrelated to the patient’s systemic and pulmonary symptoms. The providers were then able to focus on the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, with only minimal intervention for the patient’s GD (ie, oral diphenhydramine prn for pruritus).

CONCLUSION

In many cases of GD, skin biopsy can guide providers when the history and physical examination do not yield a clear diagnosis. The histopathology of affected tissue can provide invaluable information about an underlying disease process, particularly in complex cases such as this patient’s. Skin biopsy provides a minimally invasive opportunity to obtain a diagnosis in patients with a condition that affects multiple organ systems, and its use should be considered in disease processes with cutaneous manifestations.

REFERENCES

1. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2): 263-268.

2. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 part 1):653-666.

3. Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1490-1494.

4. Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover’s disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(2):83-86.

5. Ippoliti G, Paulli M, Lucioni M, et al. Grover’s disease after heart transplantation: a case report. Case Rep Transplant. 2012;2012:126592.

6. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, Brand CU. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): an analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

7. Joshi R, Taneja A. Grover’s disease with acrosyringeal acantholysis: a rare histological presentation of an uncommon disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(6):621-623.

8. Riemann H, High WA. Grover’s disease (transient and persistent acantholytic dermatosis). UpToDate. 2015. www.uptodate.com/contents/grovers-disease-transient-and-persistent-acantholytic-dermatosis. Accessed June 4, 2016.

9. Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):169-170.

10. Norman R, Chau V. Use of etanercept in treating pruritus and preventing new lesions in Grover disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):796-798.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Conditions associated with increased risk for case disease

- Outcome for the case patient

- Differential diagnosis

A 78-year-old white man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is admitted to the hospital with worsening cough, shortness of breath, and fever. His medical history is significant for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii in the past year. In the weeks preceding hospital admission, the patient developed an erythematous rash over his trunk (see photographs).

During the man’s hospital stay, this eruption becomes increasingly pruritic and spreads to his proximal extremities. His pulmonary symptoms improve slightly following the initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin), but CT performed one week after admission reveals worsening pulmonary disease (see image). The radiologist’s differential diagnosis includes neoplasm, fungal infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and autoimmune disease.

|  |

| A. The patient's back shows a distribution of lesions, with areas of excoriation caused by scratching. | B. A close-up reveals erythematous papules and keratotic papules. |

Suspecting that the progressive rash is related to the systemic process, the provider orders a punch biopsy in an effort to reach a diagnosis with minimally invasive studies. When the patient’s clinical status further declines, he undergoes video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to obtain an excisional biopsy of one of the pulmonary nodules. Subsequent analysis reveals fungal organisms consistent with histoplasmosis. Interestingly, in the histologic review of the skin biopsy, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis—suggestive of Grover disease—is identified.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Grover disease (GD), also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, is a skin condition of uncertain pathophysiology. Its clinical presentation can be difficult to distinguish from other dermopathies.1,2

Incidence

GD most commonly appears in fair-skinned persons of late middle age, with men affected at two to three times the rate seen in women.1,2 Although GD has been documented in patients ranging in age from 4 to 100, this dermopathy is rare in younger patients.1-3 Persons with a prior history of atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, or xerosis cutis are at increased risk for GD—likely due to an increased dermatologic sensitivity to irritants resulting from the aforementioned disorders.1,4 Risk for GD is also elevated in patients with chronic medical conditions, immunodeficiency, febrile illnesses, or malignancies (see Table 1).2-5

The true incidence of GD is not known; biopsy-proven GD is uncommon, and specific data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition are lacking. Swiss researchers who reviewed more than 30,000 skin biopsies in the late 1990s noted only 24 diagnosed cases of GD, and similar findings have been reported in the United States.1,6 However, the variable presentation and often mild nature of GD may result in cases of misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, or empiric treatment in the absence of a formal diagnosis.7

Causative factors

Although the pathophysiology of GD is uncertain, the most likely cause is an occlusion of the eccrine glands.3 This is followed by acantholysis, or separation of keratinocytes within the epidermis, which in turn leads to the development of vesicular lesions.

Though diagnosed most often in the winter, GD has also been associated with exposure to sunlight, heat, xerosis, and diaphoresis.1,3 Hospitalized or bedridden patients are at risk for occlusion of the eccrine glands and thus for GD. Use of certain therapies, including sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (an antimalarial treatment), ionizing radiation, and interleukin-4, may also be precursors for the condition.2

Other exacerbating factors have been suggested, but reports are largely limited to case studies and other anecdotal publications.2 Concrete data regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of GD are still relatively scarce.

Clinical presentation

Patients with GD present with pruritic dermatitis on the trunk and proximal extremities, most classically on the anterior chest and mid back.2,3 The severity of the rash does not necessarily correlate to the degree of pruritus. Some patients report only mild pruritus, while others experience debilitating discomfort and pain. In most cases, erythematous and violaceous papules and vesicles appear first, followed by keratotic erosions.3

GD is a self-limited disorder that often resolves within a few weeks, although some cases will persist for several months.3,5 Severity and duration of symptoms appear to be correlated with increasing age; elderly patients experience worse pruritus for longer periods than do younger patients.2

Although the condition is sometimes referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis, there are three typical presentations of GD: transient eruptive, persistent pruritic, and chronic asymptomatic.4 Transient eruptive GD presents suddenly, with intense pruritus, and tends to subside over several weeks. Persistent pruritic disease generally causes a milder pruritus, with symptoms that last for several months and are not well controlled by medication. Chronic asymptomatic GD can be difficult to treat medically, yet this form of the disease typically causes little to no irritation and requires minimal therapeutic intervention.4

Systemic symptoms of GD have not been observed. Pruritus and rash are the main features in most affected patients. However, pruritic papulovesicular eruptions are commonly seen in other conditions with similar characteristics (see Table 2,3,4), and GD is comparatively rare. While clinical appearance alone may suggest a diagnosis of GD, further testing may be needed to eliminate other conditions from the differential.

Treatment and prognosis

In the absence of randomized therapeutic trials for GD, there are no strict guidelines for treatment. When irritation, inflammation, and pruritus become bothersome, several interventions may be considered. The first step may consist of efforts to modify aggravating factors, such as dry skin, occlusion, excess heat, and rapid temperature changes. Indeed, for mild cases of GD, this may be all that is required.

The firstline pharmacotherapy for GD is medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroids, which reduce inflammation and pruritus in approximately half of affected patients.3,6,8 Topical emollients and oral antihistamines can also provide symptom relief. Vitamin D analogues are considered secondline therapy, and retinoids (both topical and systemic) have also been shown to reduce GD severity.3,4,8

Severe, refractory cases may require more aggressive systemic therapy with corticosteroids or retinoids. For pruritic relief, several weeks of oral corticosteroids may be necessary—and GD may rebound after treatment ceases.3,4 Therefore, oral corticosteroids should only be considered for severe or persistent cases, since the systemic adverse effects (eg, immunosuppression, weight gain, dysglycemia) of these drugs may outweigh the benefits in patients with GD. Other interventions, including phototherapy and immunosuppressive drugs (eg, etanercept) have also demonstrated benefit in select patients.4,9,10

The self-limited nature of GD, along with its lack of systemic symptoms, is associated with a generally benign course of disease and no long-term sequelae.3,5

Continue to outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

This case involved an immunocompromised patient with systemic symptoms, vasculitic cutaneous lesions, and significant pulmonary disease. The differential diagnosis was extensive, and diagnosis based on clinical grounds alone was extremely challenging. In these circumstances, diagnostic testing was essential to reach a final diagnosis.

In this case, the skin biopsy yielded a diagnosis of GD, and the rash was found to be unrelated to the patient’s systemic and pulmonary symptoms. The providers were then able to focus on the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, with only minimal intervention for the patient’s GD (ie, oral diphenhydramine prn for pruritus).

CONCLUSION

In many cases of GD, skin biopsy can guide providers when the history and physical examination do not yield a clear diagnosis. The histopathology of affected tissue can provide invaluable information about an underlying disease process, particularly in complex cases such as this patient’s. Skin biopsy provides a minimally invasive opportunity to obtain a diagnosis in patients with a condition that affects multiple organ systems, and its use should be considered in disease processes with cutaneous manifestations.

REFERENCES

1. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2): 263-268.

2. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 part 1):653-666.

3. Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1490-1494.

4. Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover’s disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(2):83-86.

5. Ippoliti G, Paulli M, Lucioni M, et al. Grover’s disease after heart transplantation: a case report. Case Rep Transplant. 2012;2012:126592.

6. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, Brand CU. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): an analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

7. Joshi R, Taneja A. Grover’s disease with acrosyringeal acantholysis: a rare histological presentation of an uncommon disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(6):621-623.

8. Riemann H, High WA. Grover’s disease (transient and persistent acantholytic dermatosis). UpToDate. 2015. www.uptodate.com/contents/grovers-disease-transient-and-persistent-acantholytic-dermatosis. Accessed June 4, 2016.

9. Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):169-170.

10. Norman R, Chau V. Use of etanercept in treating pruritus and preventing new lesions in Grover disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):796-798.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Conditions associated with increased risk for case disease

- Outcome for the case patient

- Differential diagnosis

A 78-year-old white man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is admitted to the hospital with worsening cough, shortness of breath, and fever. His medical history is significant for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii in the past year. In the weeks preceding hospital admission, the patient developed an erythematous rash over his trunk (see photographs).

During the man’s hospital stay, this eruption becomes increasingly pruritic and spreads to his proximal extremities. His pulmonary symptoms improve slightly following the initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin), but CT performed one week after admission reveals worsening pulmonary disease (see image). The radiologist’s differential diagnosis includes neoplasm, fungal infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and autoimmune disease.

|  |

| A. The patient's back shows a distribution of lesions, with areas of excoriation caused by scratching. | B. A close-up reveals erythematous papules and keratotic papules. |

Suspecting that the progressive rash is related to the systemic process, the provider orders a punch biopsy in an effort to reach a diagnosis with minimally invasive studies. When the patient’s clinical status further declines, he undergoes video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to obtain an excisional biopsy of one of the pulmonary nodules. Subsequent analysis reveals fungal organisms consistent with histoplasmosis. Interestingly, in the histologic review of the skin biopsy, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis—suggestive of Grover disease—is identified.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Grover disease (GD), also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, is a skin condition of uncertain pathophysiology. Its clinical presentation can be difficult to distinguish from other dermopathies.1,2

Incidence

GD most commonly appears in fair-skinned persons of late middle age, with men affected at two to three times the rate seen in women.1,2 Although GD has been documented in patients ranging in age from 4 to 100, this dermopathy is rare in younger patients.1-3 Persons with a prior history of atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, or xerosis cutis are at increased risk for GD—likely due to an increased dermatologic sensitivity to irritants resulting from the aforementioned disorders.1,4 Risk for GD is also elevated in patients with chronic medical conditions, immunodeficiency, febrile illnesses, or malignancies (see Table 1).2-5

The true incidence of GD is not known; biopsy-proven GD is uncommon, and specific data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition are lacking. Swiss researchers who reviewed more than 30,000 skin biopsies in the late 1990s noted only 24 diagnosed cases of GD, and similar findings have been reported in the United States.1,6 However, the variable presentation and often mild nature of GD may result in cases of misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, or empiric treatment in the absence of a formal diagnosis.7

Causative factors

Although the pathophysiology of GD is uncertain, the most likely cause is an occlusion of the eccrine glands.3 This is followed by acantholysis, or separation of keratinocytes within the epidermis, which in turn leads to the development of vesicular lesions.

Though diagnosed most often in the winter, GD has also been associated with exposure to sunlight, heat, xerosis, and diaphoresis.1,3 Hospitalized or bedridden patients are at risk for occlusion of the eccrine glands and thus for GD. Use of certain therapies, including sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (an antimalarial treatment), ionizing radiation, and interleukin-4, may also be precursors for the condition.2

Other exacerbating factors have been suggested, but reports are largely limited to case studies and other anecdotal publications.2 Concrete data regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of GD are still relatively scarce.

Clinical presentation

Patients with GD present with pruritic dermatitis on the trunk and proximal extremities, most classically on the anterior chest and mid back.2,3 The severity of the rash does not necessarily correlate to the degree of pruritus. Some patients report only mild pruritus, while others experience debilitating discomfort and pain. In most cases, erythematous and violaceous papules and vesicles appear first, followed by keratotic erosions.3

GD is a self-limited disorder that often resolves within a few weeks, although some cases will persist for several months.3,5 Severity and duration of symptoms appear to be correlated with increasing age; elderly patients experience worse pruritus for longer periods than do younger patients.2

Although the condition is sometimes referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis, there are three typical presentations of GD: transient eruptive, persistent pruritic, and chronic asymptomatic.4 Transient eruptive GD presents suddenly, with intense pruritus, and tends to subside over several weeks. Persistent pruritic disease generally causes a milder pruritus, with symptoms that last for several months and are not well controlled by medication. Chronic asymptomatic GD can be difficult to treat medically, yet this form of the disease typically causes little to no irritation and requires minimal therapeutic intervention.4

Systemic symptoms of GD have not been observed. Pruritus and rash are the main features in most affected patients. However, pruritic papulovesicular eruptions are commonly seen in other conditions with similar characteristics (see Table 2,3,4), and GD is comparatively rare. While clinical appearance alone may suggest a diagnosis of GD, further testing may be needed to eliminate other conditions from the differential.

Treatment and prognosis

In the absence of randomized therapeutic trials for GD, there are no strict guidelines for treatment. When irritation, inflammation, and pruritus become bothersome, several interventions may be considered. The first step may consist of efforts to modify aggravating factors, such as dry skin, occlusion, excess heat, and rapid temperature changes. Indeed, for mild cases of GD, this may be all that is required.

The firstline pharmacotherapy for GD is medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroids, which reduce inflammation and pruritus in approximately half of affected patients.3,6,8 Topical emollients and oral antihistamines can also provide symptom relief. Vitamin D analogues are considered secondline therapy, and retinoids (both topical and systemic) have also been shown to reduce GD severity.3,4,8

Severe, refractory cases may require more aggressive systemic therapy with corticosteroids or retinoids. For pruritic relief, several weeks of oral corticosteroids may be necessary—and GD may rebound after treatment ceases.3,4 Therefore, oral corticosteroids should only be considered for severe or persistent cases, since the systemic adverse effects (eg, immunosuppression, weight gain, dysglycemia) of these drugs may outweigh the benefits in patients with GD. Other interventions, including phototherapy and immunosuppressive drugs (eg, etanercept) have also demonstrated benefit in select patients.4,9,10

The self-limited nature of GD, along with its lack of systemic symptoms, is associated with a generally benign course of disease and no long-term sequelae.3,5

Continue to outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

This case involved an immunocompromised patient with systemic symptoms, vasculitic cutaneous lesions, and significant pulmonary disease. The differential diagnosis was extensive, and diagnosis based on clinical grounds alone was extremely challenging. In these circumstances, diagnostic testing was essential to reach a final diagnosis.

In this case, the skin biopsy yielded a diagnosis of GD, and the rash was found to be unrelated to the patient’s systemic and pulmonary symptoms. The providers were then able to focus on the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, with only minimal intervention for the patient’s GD (ie, oral diphenhydramine prn for pruritus).

CONCLUSION

In many cases of GD, skin biopsy can guide providers when the history and physical examination do not yield a clear diagnosis. The histopathology of affected tissue can provide invaluable information about an underlying disease process, particularly in complex cases such as this patient’s. Skin biopsy provides a minimally invasive opportunity to obtain a diagnosis in patients with a condition that affects multiple organ systems, and its use should be considered in disease processes with cutaneous manifestations.

REFERENCES

1. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2): 263-268.

2. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 part 1):653-666.

3. Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1490-1494.

4. Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover’s disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(2):83-86.

5. Ippoliti G, Paulli M, Lucioni M, et al. Grover’s disease after heart transplantation: a case report. Case Rep Transplant. 2012;2012:126592.

6. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, Brand CU. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): an analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

7. Joshi R, Taneja A. Grover’s disease with acrosyringeal acantholysis: a rare histological presentation of an uncommon disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(6):621-623.

8. Riemann H, High WA. Grover’s disease (transient and persistent acantholytic dermatosis). UpToDate. 2015. www.uptodate.com/contents/grovers-disease-transient-and-persistent-acantholytic-dermatosis. Accessed June 4, 2016.

9. Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):169-170.

10. Norman R, Chau V. Use of etanercept in treating pruritus and preventing new lesions in Grover disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):796-798.