User login

Timely Epinephrine for Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

BY MARY ANN MOON

FROM JAMA

Vitals Key clinical point: Delay in administering epinephrine was linked to poorer outcomes in pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest. Major finding: Delay in epinephrine treatment was significantly associated with a lower chance of survival to hospital discharge (relative risk [RR], 0.95 per minute of delay). Data source: A multicenter cohort study of 1,558 in-hospital cardiac arrests among pediatric patients across the United States during a 15-year period. Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American Heart Association (AHA) supported the study. Dr Andersen and his associates reported having no conflicts of interest. |

Delay in administering epinephrine is associated with significantly poorer outcomes among pediatric patients who have in-hospital cardiac arrest with an nonshockable rhythm, according to a report published in JAMA.1

For the approximately 16,000 US children and adolescents in this patient population each year, epinephrine is the recommended first-line pharmacologic therapy, even though no randomized placebo-controlled trials have ever been performed to support this practice.

“It is highly unlikely that any such study will ever be done, given the ethical considerations; so to examine the effect of the timing of epinephrine therapy, investigators analyzed data from the Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation registry concerning 1,558 patients aged 0-18 years who were treated during a 15-year period,” said Dr Lars W. Andersen of the department of emergency medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts and the department of anesthesiology at Aarhus (Denmark) University and his associates.1

All the patients received chest compressions and at least one epinephrine bolus while pulseless with a documented nonshockable initial rhythm. The median age was 9 months, and the median time to first epinephrine dose was 1 minute (range, 0-20 minutes). A total of 37% of these patients received their first dose of epinephrine within 1 minute after loss of pulse was noted, and 15% received their first dose more than 5 minutes afterward.

Delay in epinephrine treatment was significantly associated with a lower chance of survival to hospital discharge (RR, 0.95 per minute of delay), the primary outcome measure of the study. In addition, longer time to epinephrine delivery was significantly associated with a decreased chance of return to spontaneous circulation (RR, 0.97 per minute of delay), for survival at 24 hours (RR, 0.97 per minute of delay), and for survival with favorable neurologic outcome (RR, 0.95 per minute of delay).

In a further analysis of the data, patients were divided into two groups according to the length of time before epinephrine administration. The 1,325 patients who received epinephrine within 5 minutes had a 33.1% rate of survival to hospital discharge, while the 233 who received epinephrine after 5 minutes had elapsed had a significantly lower 21.0% rate of survival to hospital discharge, Dr Andersen and his associates said.

These findings suggest, but cannot establish, that treatment delay causes poorer outcomes because an observational study cannot determine causality. Even though the data were adjusted to account for numerous patient and hospital characteristics, and even though the results remained robust through multiple sensitivity analyses, it remains possible that time to epinephrine administration is not a causal mediator but a marker of other aspects of the resuscitation process, the researchers added.

The findings by Dr Andersen and his associates provide fairly strong evidence that following current guidelines for epinephrine timing is best practice, supporting an AHA class I strength of recommendation.1

The investigators are correct to note that observational data cannot establish causality. Almost all of these cardiac arrests were witnessed; approximately two-thirds occurred in the pediatric intensive care unit, operating room, or postanesthesia setting; and half of the patients were receiving mechanical ventilation. So it is possible that the link between timing of epinephrine and outcomes may simply reflect factors such as the circumstances of the cardiac arrest, the presence of an airway and intravenous access, or the quality of chest compressions.

Dr Robert C. Tasker and Dr Adriennne G. Randolph are with the division of critical care medicine, department of anesthesia, perioperative, and pain medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital and the department of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School. Dr Tasker is also with the department of neurology at both institutions and Dr Randolph is also with the department of pediatrics at Harvard. Both authors reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr Tasker and Dr Randolph made these remarks in an accompanying editorial.2

ED Care Pathway Hastens Febrile Neutropenia Therapy

BY Kari Oakes

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Vitals Key clinical point: Instituting a care pathway hastened antibiotic administration in cancer patients with fever in the ED. Major finding: Cancer patients treated according to a febrile neutropenia care pathway in the ED received antibiotics in 81 minutes, significantly sooner than did historical and direct admission comparison cohorts at 235 and 169 minutes, respectively (P<.001 for both differences). Data source: Prospective study of 276 febrile neutropenia episodes in 223 patients, compared with 107 episodes in 87 historical patients and 114 episodes in 101 direct admission cohort patients. Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. |

Cancer patients who arrive in the ED with febrile neutropenia (FN) received antibiotics much more quickly when their condition was identified as a medical emergency and a care pathway was used to guide treatment. The set of simple interventions slashed average time to antibiotics from about 4 hours to less than 1.5 hours, compared with a historical cohort, and the inexpensive interventions have had durable results.

Dr Michael Keng and his coinvestigators at the Cleveland Clinic reported the results of a single-center prospective analysis that targeted FN, a common and serious chemotherapy complication with a mortality rate that can exceed 50% in medically fragile individuals.1

“With an increasing number of outpatient chemotherapy regimens, more patients are likely to present to the emergency department with FN,” wrote Dr Keng. The FN pathway devised by Dr Keng and his associates implemented key changes designed to identify FN as an emergency and guide prompt triage, assessment, and treatment.

Study coauthor Dr Mikkael Sekeres said, “The interventions were not complicated. We standardized our definition of fever, provided patients with wallet-sized cards alerting emergency departments to the potential of this serious condition, worked with our emergency department staff to change the triage level of fever and neutropenia to be equivalent to that observed for heart attack or stroke, designed standard febrile neutropenia order sets for our electronic medical record, and relocated the antibiotics used to treat febrile neutropenia to our emergency department.”

Febrile patients with cancer in the prospective cohort (n = 223) were compared with a historical cohort of patients presenting to the ED who received usual care (n = 87), as well as to a concurrent cohort of patients who were directly admitted to the hospital (n = 114). The total number of FN episodes for the cohorts was 276, 107, and 114, respectively. Multivariable analysis was used to account for some differences in patient characteristics across cohorts.

Using the order set in the electronic health record (EHR) also made a difference: for those treated per the order set (n = 103), median time to antibiotics was 68 minutes, compared with 96 minutes when the order set was not used.

Secondary outcome measures included times to physician assessment, blood draw, and antibiotic order placement. All measures except time to physician assessment were significantly shorter for the FN pathway group than for the comparison cohorts (P<.001 for all).

Since so many changes were made at once, Dr Keng and his coauthors noted, “It is difficult to determine the impact of any one change.” Some institutions may have difficulty implementing all the interventions, but immediate triage, automated antibiotic ordering, and EHR use were the changes that had the most impact, he wrote.

“Instituting these changes took less than half a year, and the benefits have persisted for years afterward,” Dr Sekeres said in an interview.

ESC: Aldosterone Blockade Fails to Fly for Early MI in ALBATROSS

BY BRUCE JANCIN

AT THE European Society of Cardiology CONGRESS 2015

Vitals Key clinical point: Giving aldosterone antagonists to myocardial infarction (MI) patients without heart failure doesn’t improve clinical outcomes. Major finding: The 6-month rate of a multipronged composite clinical endpoint was closely similar, regardless of whether patients with acute MI without heart failure were placed on spironolactone within the first couple of days post-MI. Data source: The Aldosterone Lethal Effects Blockade in Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated With or Without Reperfusion to Improve Outcome and Survival at Six Months’ Follow-Up (ALBATROSS) trial was an open-label, multicenter French study in which 1,603 patients were randomized to 6 months of aldosterone blockade or not within the first hours after an acute MI without heart failure. Disclosures: The investigator-initiated ALBATROSS trial was funded by the French Ministry of Health. |

LONDON – Aldosterone blockade with oral spironolactone showed a disappointing lack of clinical benefit when initiated in the first hours after an acute MI without heart failure in the large, randomized ALBATROSS trial.

ALBATROSS did, however, flash a silver lining under one wing: A whopping 80% reduction in 6-month mortality in a prespecified subgroup analysis restricted to the 1,229 participants with ST-elevation MI, Dr Gilles Montalescot reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although this finding is intriguing, hypothesis-generating, and definitely warrants a confirmatory study, he continued, mortality was nevertheless merely a secondary endpoint in ALBATROSS.

In contrast, the primary composite outcome was negative, so the takeaway message is clear: “The results of the ALBATROSS study do not warrant the extension of aldosterone blockade to MI patients without heart failure,” said Dr Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris.

ALBATROSS was a multicenter French trial that randomly assigned 1,603 acute MI patients to standard therapy alone or with added mineralocorticoid antagonist therapy started within the first 2 days of their coronary event. Often the aldosterone antagonist was begun in the ambulance en route to the hospital.1

The primary endpoint was a composite of death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia, heart failure, or an indication for an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. There were 194 such events, and they occurred at a similar rate in the patients who got 25 mg/day of spironolactone and those who did not.

The rationale for ALBATROSS was sound, according to the cardiologist. Aldosterone is a stress hormone released in acute MI. It has deleterious cardiac effects, including arrhythmias, heart failure, and a dose-dependent increase in mortality, so it makes good sense to block it as soon as possible in MI patients. In the Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (EPHESUS) trial, the aldosterone antagonist eplerenone, when started 3-14 days post MI in patients with early heart failure, significantly reduced mortality,2 with the bulk of the benefit occurring in patients in whom the drug was started 3-7 days post MI.

Last year, Dr Montalescot and his coinvestigators published the Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial Evaluating The Safety and Efficacy of Early Treatment With Eplerenone in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (REMINDER) study, in which 1,012 ST-elevation MI (STEMI) patients without heart failure were randomized to eplerenone or placebo within the first 24 hours. The study showed a significant reduction in levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP in the eplerenone arm,2 but that’s not a clinical endpoint. ALBATROSS was the first study to look at the clinical impact of commencing mineralocorticoid antagonist therapy prior to day 3 post-MI.

Discussant Dr John McMurray, professor of cardiology at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, said that ALBATROSS was simply underpowered and thus leaves unanswered the clinically important question of whether early initiation of aldosterone blockade post MI in patients without heart failure confers clinical benefit. The investigators projected a total of 269 events in the composite endpoint but got only 194 because the study participants were so well treated and contemporary medical and interventional therapies are quite effective.

He dismissed the sharp reduction seen in 6-month mortality with spironolactone in the STEMI patients as “just implausible—we don’t know of any treatments in medicine that reduce mortality by 80%.”

Noting that there were only 28 deaths in the study, Dr McMurray asserted that “a subgroup analysis on such a small number of events is never going to give you a reliable result.” Moreover, he added, “subgroup analysis is even more treacherous when the overall trial is underpowered.”

Dr Montalescot replied that, while he considers the signal of a mortality benefit for aldosterone blockade in STEMI patients worthy of pursuit in a large randomized trial, the prospects for mounting such a study are poor. The medications are now available as generics, so there is no commercial incentive. The French Ministry of Health, which funded ALBATROSS, isn’t prepared to back a follow-up study. The best hope is that eventually one of the pharmaceutical companies developing third-generation aldosterone antagonists, now in phase II studies, will become interested, he said.

Dr Montalescot said that, while he receives research grants and consulting fees from numerous pharmaceutical companies, these commercial relationships aren’t relevant to the government-funded ALBATROSS trial.

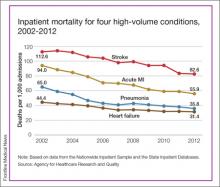

Inpatient Mortality Down for High-Volume Conditions

BY RICHARD FRANKI

Frontline Medical News

Over that period, mortality among adults hospitalized with pneumonia went from 65 per 1,000 admissions to 35.8 per 1,000 for a drop of 45%—the largest of the four high-volume conditions. Corresponding declines for the others were 41% for acute MI, 29% for heart failure, and 27% for stroke, the AHRQ noted.

Since “death following discharge from a hospital is not reflected in these data,” the report said, measures of inpatient mortality “can reflect both improvements in health care and shifts in where end-of-life care takes place over time.”

The estimates in the report are based on data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (2002-2011) and State Inpatient Databases (2012).1

- Timely Epinephrine for Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

- Andersen LW, Berg, KM, Saindon BZ, et al; American Heart Associaton Get With the Guidelines—Resuscitation Investigators. Time to epinephrine and survival after pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2015;314(8):802-810.

- Tasker RC, Randolph AG. Pediatric pulseless arrest with “nonshockable” rhythm: does faster time to epinephrine improve outsome? JAMA. 2015;314(8):776-777.

- ED Care Pathway Hastens Febrile Neutropenia Therapy

- Keng MK, Thallner EA, Elson P, et al. Reducing time to antibiotic administration for febrile neutropenia in the emergency department [published online ahead of print July 28, 2015]. J Oncol Pract.

- ESC: Aldosterone Blockade Fails to Fly for Early MI in ALBATROSS

- Aldosterone Lethal Effects Blocked in AMI Treated With or Without Reperfusion to Improve Outcome and Survival at Six Months Follow-up: THE ALBATROSS TRIAL. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2015 September 14. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01059136.

- Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, et al; Eplerenon Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study Investigators. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(14)1309-1321.

- Inpatient Mortality Down for High-Volume Conditions

- Statistical Brief #194. Trends in Observed Adult Inpatient Mortality for High-Volume Conditions, 2002-2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). July 2015. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb194-Inpatient-Mortality-High-Volume-Conditions.jsp. Accessed August 20, 2015.

Timely Epinephrine for Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

BY MARY ANN MOON

FROM JAMA

Vitals Key clinical point: Delay in administering epinephrine was linked to poorer outcomes in pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest. Major finding: Delay in epinephrine treatment was significantly associated with a lower chance of survival to hospital discharge (relative risk [RR], 0.95 per minute of delay). Data source: A multicenter cohort study of 1,558 in-hospital cardiac arrests among pediatric patients across the United States during a 15-year period. Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American Heart Association (AHA) supported the study. Dr Andersen and his associates reported having no conflicts of interest. |

Delay in administering epinephrine is associated with significantly poorer outcomes among pediatric patients who have in-hospital cardiac arrest with an nonshockable rhythm, according to a report published in JAMA.1

For the approximately 16,000 US children and adolescents in this patient population each year, epinephrine is the recommended first-line pharmacologic therapy, even though no randomized placebo-controlled trials have ever been performed to support this practice.

“It is highly unlikely that any such study will ever be done, given the ethical considerations; so to examine the effect of the timing of epinephrine therapy, investigators analyzed data from the Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation registry concerning 1,558 patients aged 0-18 years who were treated during a 15-year period,” said Dr Lars W. Andersen of the department of emergency medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts and the department of anesthesiology at Aarhus (Denmark) University and his associates.1

All the patients received chest compressions and at least one epinephrine bolus while pulseless with a documented nonshockable initial rhythm. The median age was 9 months, and the median time to first epinephrine dose was 1 minute (range, 0-20 minutes). A total of 37% of these patients received their first dose of epinephrine within 1 minute after loss of pulse was noted, and 15% received their first dose more than 5 minutes afterward.

Delay in epinephrine treatment was significantly associated with a lower chance of survival to hospital discharge (RR, 0.95 per minute of delay), the primary outcome measure of the study. In addition, longer time to epinephrine delivery was significantly associated with a decreased chance of return to spontaneous circulation (RR, 0.97 per minute of delay), for survival at 24 hours (RR, 0.97 per minute of delay), and for survival with favorable neurologic outcome (RR, 0.95 per minute of delay).

In a further analysis of the data, patients were divided into two groups according to the length of time before epinephrine administration. The 1,325 patients who received epinephrine within 5 minutes had a 33.1% rate of survival to hospital discharge, while the 233 who received epinephrine after 5 minutes had elapsed had a significantly lower 21.0% rate of survival to hospital discharge, Dr Andersen and his associates said.

These findings suggest, but cannot establish, that treatment delay causes poorer outcomes because an observational study cannot determine causality. Even though the data were adjusted to account for numerous patient and hospital characteristics, and even though the results remained robust through multiple sensitivity analyses, it remains possible that time to epinephrine administration is not a causal mediator but a marker of other aspects of the resuscitation process, the researchers added.

The findings by Dr Andersen and his associates provide fairly strong evidence that following current guidelines for epinephrine timing is best practice, supporting an AHA class I strength of recommendation.1

The investigators are correct to note that observational data cannot establish causality. Almost all of these cardiac arrests were witnessed; approximately two-thirds occurred in the pediatric intensive care unit, operating room, or postanesthesia setting; and half of the patients were receiving mechanical ventilation. So it is possible that the link between timing of epinephrine and outcomes may simply reflect factors such as the circumstances of the cardiac arrest, the presence of an airway and intravenous access, or the quality of chest compressions.

Dr Robert C. Tasker and Dr Adriennne G. Randolph are with the division of critical care medicine, department of anesthesia, perioperative, and pain medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital and the department of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School. Dr Tasker is also with the department of neurology at both institutions and Dr Randolph is also with the department of pediatrics at Harvard. Both authors reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr Tasker and Dr Randolph made these remarks in an accompanying editorial.2

ED Care Pathway Hastens Febrile Neutropenia Therapy

BY Kari Oakes

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Vitals Key clinical point: Instituting a care pathway hastened antibiotic administration in cancer patients with fever in the ED. Major finding: Cancer patients treated according to a febrile neutropenia care pathway in the ED received antibiotics in 81 minutes, significantly sooner than did historical and direct admission comparison cohorts at 235 and 169 minutes, respectively (P<.001 for both differences). Data source: Prospective study of 276 febrile neutropenia episodes in 223 patients, compared with 107 episodes in 87 historical patients and 114 episodes in 101 direct admission cohort patients. Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. |

Cancer patients who arrive in the ED with febrile neutropenia (FN) received antibiotics much more quickly when their condition was identified as a medical emergency and a care pathway was used to guide treatment. The set of simple interventions slashed average time to antibiotics from about 4 hours to less than 1.5 hours, compared with a historical cohort, and the inexpensive interventions have had durable results.

Dr Michael Keng and his coinvestigators at the Cleveland Clinic reported the results of a single-center prospective analysis that targeted FN, a common and serious chemotherapy complication with a mortality rate that can exceed 50% in medically fragile individuals.1

“With an increasing number of outpatient chemotherapy regimens, more patients are likely to present to the emergency department with FN,” wrote Dr Keng. The FN pathway devised by Dr Keng and his associates implemented key changes designed to identify FN as an emergency and guide prompt triage, assessment, and treatment.

Study coauthor Dr Mikkael Sekeres said, “The interventions were not complicated. We standardized our definition of fever, provided patients with wallet-sized cards alerting emergency departments to the potential of this serious condition, worked with our emergency department staff to change the triage level of fever and neutropenia to be equivalent to that observed for heart attack or stroke, designed standard febrile neutropenia order sets for our electronic medical record, and relocated the antibiotics used to treat febrile neutropenia to our emergency department.”

Febrile patients with cancer in the prospective cohort (n = 223) were compared with a historical cohort of patients presenting to the ED who received usual care (n = 87), as well as to a concurrent cohort of patients who were directly admitted to the hospital (n = 114). The total number of FN episodes for the cohorts was 276, 107, and 114, respectively. Multivariable analysis was used to account for some differences in patient characteristics across cohorts.

Using the order set in the electronic health record (EHR) also made a difference: for those treated per the order set (n = 103), median time to antibiotics was 68 minutes, compared with 96 minutes when the order set was not used.

Secondary outcome measures included times to physician assessment, blood draw, and antibiotic order placement. All measures except time to physician assessment were significantly shorter for the FN pathway group than for the comparison cohorts (P<.001 for all).

Since so many changes were made at once, Dr Keng and his coauthors noted, “It is difficult to determine the impact of any one change.” Some institutions may have difficulty implementing all the interventions, but immediate triage, automated antibiotic ordering, and EHR use were the changes that had the most impact, he wrote.

“Instituting these changes took less than half a year, and the benefits have persisted for years afterward,” Dr Sekeres said in an interview.

ESC: Aldosterone Blockade Fails to Fly for Early MI in ALBATROSS

BY BRUCE JANCIN

AT THE European Society of Cardiology CONGRESS 2015

Vitals Key clinical point: Giving aldosterone antagonists to myocardial infarction (MI) patients without heart failure doesn’t improve clinical outcomes. Major finding: The 6-month rate of a multipronged composite clinical endpoint was closely similar, regardless of whether patients with acute MI without heart failure were placed on spironolactone within the first couple of days post-MI. Data source: The Aldosterone Lethal Effects Blockade in Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated With or Without Reperfusion to Improve Outcome and Survival at Six Months’ Follow-Up (ALBATROSS) trial was an open-label, multicenter French study in which 1,603 patients were randomized to 6 months of aldosterone blockade or not within the first hours after an acute MI without heart failure. Disclosures: The investigator-initiated ALBATROSS trial was funded by the French Ministry of Health. |

LONDON – Aldosterone blockade with oral spironolactone showed a disappointing lack of clinical benefit when initiated in the first hours after an acute MI without heart failure in the large, randomized ALBATROSS trial.

ALBATROSS did, however, flash a silver lining under one wing: A whopping 80% reduction in 6-month mortality in a prespecified subgroup analysis restricted to the 1,229 participants with ST-elevation MI, Dr Gilles Montalescot reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although this finding is intriguing, hypothesis-generating, and definitely warrants a confirmatory study, he continued, mortality was nevertheless merely a secondary endpoint in ALBATROSS.

In contrast, the primary composite outcome was negative, so the takeaway message is clear: “The results of the ALBATROSS study do not warrant the extension of aldosterone blockade to MI patients without heart failure,” said Dr Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris.

ALBATROSS was a multicenter French trial that randomly assigned 1,603 acute MI patients to standard therapy alone or with added mineralocorticoid antagonist therapy started within the first 2 days of their coronary event. Often the aldosterone antagonist was begun in the ambulance en route to the hospital.1

The primary endpoint was a composite of death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia, heart failure, or an indication for an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. There were 194 such events, and they occurred at a similar rate in the patients who got 25 mg/day of spironolactone and those who did not.

The rationale for ALBATROSS was sound, according to the cardiologist. Aldosterone is a stress hormone released in acute MI. It has deleterious cardiac effects, including arrhythmias, heart failure, and a dose-dependent increase in mortality, so it makes good sense to block it as soon as possible in MI patients. In the Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (EPHESUS) trial, the aldosterone antagonist eplerenone, when started 3-14 days post MI in patients with early heart failure, significantly reduced mortality,2 with the bulk of the benefit occurring in patients in whom the drug was started 3-7 days post MI.

Last year, Dr Montalescot and his coinvestigators published the Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial Evaluating The Safety and Efficacy of Early Treatment With Eplerenone in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (REMINDER) study, in which 1,012 ST-elevation MI (STEMI) patients without heart failure were randomized to eplerenone or placebo within the first 24 hours. The study showed a significant reduction in levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP in the eplerenone arm,2 but that’s not a clinical endpoint. ALBATROSS was the first study to look at the clinical impact of commencing mineralocorticoid antagonist therapy prior to day 3 post-MI.

Discussant Dr John McMurray, professor of cardiology at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, said that ALBATROSS was simply underpowered and thus leaves unanswered the clinically important question of whether early initiation of aldosterone blockade post MI in patients without heart failure confers clinical benefit. The investigators projected a total of 269 events in the composite endpoint but got only 194 because the study participants were so well treated and contemporary medical and interventional therapies are quite effective.

He dismissed the sharp reduction seen in 6-month mortality with spironolactone in the STEMI patients as “just implausible—we don’t know of any treatments in medicine that reduce mortality by 80%.”

Noting that there were only 28 deaths in the study, Dr McMurray asserted that “a subgroup analysis on such a small number of events is never going to give you a reliable result.” Moreover, he added, “subgroup analysis is even more treacherous when the overall trial is underpowered.”

Dr Montalescot replied that, while he considers the signal of a mortality benefit for aldosterone blockade in STEMI patients worthy of pursuit in a large randomized trial, the prospects for mounting such a study are poor. The medications are now available as generics, so there is no commercial incentive. The French Ministry of Health, which funded ALBATROSS, isn’t prepared to back a follow-up study. The best hope is that eventually one of the pharmaceutical companies developing third-generation aldosterone antagonists, now in phase II studies, will become interested, he said.

Dr Montalescot said that, while he receives research grants and consulting fees from numerous pharmaceutical companies, these commercial relationships aren’t relevant to the government-funded ALBATROSS trial.

Inpatient Mortality Down for High-Volume Conditions

BY RICHARD FRANKI

Frontline Medical News

Over that period, mortality among adults hospitalized with pneumonia went from 65 per 1,000 admissions to 35.8 per 1,000 for a drop of 45%—the largest of the four high-volume conditions. Corresponding declines for the others were 41% for acute MI, 29% for heart failure, and 27% for stroke, the AHRQ noted.

Since “death following discharge from a hospital is not reflected in these data,” the report said, measures of inpatient mortality “can reflect both improvements in health care and shifts in where end-of-life care takes place over time.”

The estimates in the report are based on data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (2002-2011) and State Inpatient Databases (2012).1

Timely Epinephrine for Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

BY MARY ANN MOON

FROM JAMA

Vitals Key clinical point: Delay in administering epinephrine was linked to poorer outcomes in pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest. Major finding: Delay in epinephrine treatment was significantly associated with a lower chance of survival to hospital discharge (relative risk [RR], 0.95 per minute of delay). Data source: A multicenter cohort study of 1,558 in-hospital cardiac arrests among pediatric patients across the United States during a 15-year period. Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American Heart Association (AHA) supported the study. Dr Andersen and his associates reported having no conflicts of interest. |

Delay in administering epinephrine is associated with significantly poorer outcomes among pediatric patients who have in-hospital cardiac arrest with an nonshockable rhythm, according to a report published in JAMA.1

For the approximately 16,000 US children and adolescents in this patient population each year, epinephrine is the recommended first-line pharmacologic therapy, even though no randomized placebo-controlled trials have ever been performed to support this practice.

“It is highly unlikely that any such study will ever be done, given the ethical considerations; so to examine the effect of the timing of epinephrine therapy, investigators analyzed data from the Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation registry concerning 1,558 patients aged 0-18 years who were treated during a 15-year period,” said Dr Lars W. Andersen of the department of emergency medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts and the department of anesthesiology at Aarhus (Denmark) University and his associates.1

All the patients received chest compressions and at least one epinephrine bolus while pulseless with a documented nonshockable initial rhythm. The median age was 9 months, and the median time to first epinephrine dose was 1 minute (range, 0-20 minutes). A total of 37% of these patients received their first dose of epinephrine within 1 minute after loss of pulse was noted, and 15% received their first dose more than 5 minutes afterward.

Delay in epinephrine treatment was significantly associated with a lower chance of survival to hospital discharge (RR, 0.95 per minute of delay), the primary outcome measure of the study. In addition, longer time to epinephrine delivery was significantly associated with a decreased chance of return to spontaneous circulation (RR, 0.97 per minute of delay), for survival at 24 hours (RR, 0.97 per minute of delay), and for survival with favorable neurologic outcome (RR, 0.95 per minute of delay).

In a further analysis of the data, patients were divided into two groups according to the length of time before epinephrine administration. The 1,325 patients who received epinephrine within 5 minutes had a 33.1% rate of survival to hospital discharge, while the 233 who received epinephrine after 5 minutes had elapsed had a significantly lower 21.0% rate of survival to hospital discharge, Dr Andersen and his associates said.

These findings suggest, but cannot establish, that treatment delay causes poorer outcomes because an observational study cannot determine causality. Even though the data were adjusted to account for numerous patient and hospital characteristics, and even though the results remained robust through multiple sensitivity analyses, it remains possible that time to epinephrine administration is not a causal mediator but a marker of other aspects of the resuscitation process, the researchers added.

The findings by Dr Andersen and his associates provide fairly strong evidence that following current guidelines for epinephrine timing is best practice, supporting an AHA class I strength of recommendation.1

The investigators are correct to note that observational data cannot establish causality. Almost all of these cardiac arrests were witnessed; approximately two-thirds occurred in the pediatric intensive care unit, operating room, or postanesthesia setting; and half of the patients were receiving mechanical ventilation. So it is possible that the link between timing of epinephrine and outcomes may simply reflect factors such as the circumstances of the cardiac arrest, the presence of an airway and intravenous access, or the quality of chest compressions.

Dr Robert C. Tasker and Dr Adriennne G. Randolph are with the division of critical care medicine, department of anesthesia, perioperative, and pain medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital and the department of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School. Dr Tasker is also with the department of neurology at both institutions and Dr Randolph is also with the department of pediatrics at Harvard. Both authors reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr Tasker and Dr Randolph made these remarks in an accompanying editorial.2

ED Care Pathway Hastens Febrile Neutropenia Therapy

BY Kari Oakes

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Vitals Key clinical point: Instituting a care pathway hastened antibiotic administration in cancer patients with fever in the ED. Major finding: Cancer patients treated according to a febrile neutropenia care pathway in the ED received antibiotics in 81 minutes, significantly sooner than did historical and direct admission comparison cohorts at 235 and 169 minutes, respectively (P<.001 for both differences). Data source: Prospective study of 276 febrile neutropenia episodes in 223 patients, compared with 107 episodes in 87 historical patients and 114 episodes in 101 direct admission cohort patients. Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. |

Cancer patients who arrive in the ED with febrile neutropenia (FN) received antibiotics much more quickly when their condition was identified as a medical emergency and a care pathway was used to guide treatment. The set of simple interventions slashed average time to antibiotics from about 4 hours to less than 1.5 hours, compared with a historical cohort, and the inexpensive interventions have had durable results.

Dr Michael Keng and his coinvestigators at the Cleveland Clinic reported the results of a single-center prospective analysis that targeted FN, a common and serious chemotherapy complication with a mortality rate that can exceed 50% in medically fragile individuals.1

“With an increasing number of outpatient chemotherapy regimens, more patients are likely to present to the emergency department with FN,” wrote Dr Keng. The FN pathway devised by Dr Keng and his associates implemented key changes designed to identify FN as an emergency and guide prompt triage, assessment, and treatment.

Study coauthor Dr Mikkael Sekeres said, “The interventions were not complicated. We standardized our definition of fever, provided patients with wallet-sized cards alerting emergency departments to the potential of this serious condition, worked with our emergency department staff to change the triage level of fever and neutropenia to be equivalent to that observed for heart attack or stroke, designed standard febrile neutropenia order sets for our electronic medical record, and relocated the antibiotics used to treat febrile neutropenia to our emergency department.”

Febrile patients with cancer in the prospective cohort (n = 223) were compared with a historical cohort of patients presenting to the ED who received usual care (n = 87), as well as to a concurrent cohort of patients who were directly admitted to the hospital (n = 114). The total number of FN episodes for the cohorts was 276, 107, and 114, respectively. Multivariable analysis was used to account for some differences in patient characteristics across cohorts.

Using the order set in the electronic health record (EHR) also made a difference: for those treated per the order set (n = 103), median time to antibiotics was 68 minutes, compared with 96 minutes when the order set was not used.

Secondary outcome measures included times to physician assessment, blood draw, and antibiotic order placement. All measures except time to physician assessment were significantly shorter for the FN pathway group than for the comparison cohorts (P<.001 for all).

Since so many changes were made at once, Dr Keng and his coauthors noted, “It is difficult to determine the impact of any one change.” Some institutions may have difficulty implementing all the interventions, but immediate triage, automated antibiotic ordering, and EHR use were the changes that had the most impact, he wrote.

“Instituting these changes took less than half a year, and the benefits have persisted for years afterward,” Dr Sekeres said in an interview.

ESC: Aldosterone Blockade Fails to Fly for Early MI in ALBATROSS

BY BRUCE JANCIN

AT THE European Society of Cardiology CONGRESS 2015

Vitals Key clinical point: Giving aldosterone antagonists to myocardial infarction (MI) patients without heart failure doesn’t improve clinical outcomes. Major finding: The 6-month rate of a multipronged composite clinical endpoint was closely similar, regardless of whether patients with acute MI without heart failure were placed on spironolactone within the first couple of days post-MI. Data source: The Aldosterone Lethal Effects Blockade in Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated With or Without Reperfusion to Improve Outcome and Survival at Six Months’ Follow-Up (ALBATROSS) trial was an open-label, multicenter French study in which 1,603 patients were randomized to 6 months of aldosterone blockade or not within the first hours after an acute MI without heart failure. Disclosures: The investigator-initiated ALBATROSS trial was funded by the French Ministry of Health. |

LONDON – Aldosterone blockade with oral spironolactone showed a disappointing lack of clinical benefit when initiated in the first hours after an acute MI without heart failure in the large, randomized ALBATROSS trial.

ALBATROSS did, however, flash a silver lining under one wing: A whopping 80% reduction in 6-month mortality in a prespecified subgroup analysis restricted to the 1,229 participants with ST-elevation MI, Dr Gilles Montalescot reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although this finding is intriguing, hypothesis-generating, and definitely warrants a confirmatory study, he continued, mortality was nevertheless merely a secondary endpoint in ALBATROSS.

In contrast, the primary composite outcome was negative, so the takeaway message is clear: “The results of the ALBATROSS study do not warrant the extension of aldosterone blockade to MI patients without heart failure,” said Dr Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris.

ALBATROSS was a multicenter French trial that randomly assigned 1,603 acute MI patients to standard therapy alone or with added mineralocorticoid antagonist therapy started within the first 2 days of their coronary event. Often the aldosterone antagonist was begun in the ambulance en route to the hospital.1

The primary endpoint was a composite of death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia, heart failure, or an indication for an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. There were 194 such events, and they occurred at a similar rate in the patients who got 25 mg/day of spironolactone and those who did not.

The rationale for ALBATROSS was sound, according to the cardiologist. Aldosterone is a stress hormone released in acute MI. It has deleterious cardiac effects, including arrhythmias, heart failure, and a dose-dependent increase in mortality, so it makes good sense to block it as soon as possible in MI patients. In the Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (EPHESUS) trial, the aldosterone antagonist eplerenone, when started 3-14 days post MI in patients with early heart failure, significantly reduced mortality,2 with the bulk of the benefit occurring in patients in whom the drug was started 3-7 days post MI.

Last year, Dr Montalescot and his coinvestigators published the Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial Evaluating The Safety and Efficacy of Early Treatment With Eplerenone in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (REMINDER) study, in which 1,012 ST-elevation MI (STEMI) patients without heart failure were randomized to eplerenone or placebo within the first 24 hours. The study showed a significant reduction in levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP in the eplerenone arm,2 but that’s not a clinical endpoint. ALBATROSS was the first study to look at the clinical impact of commencing mineralocorticoid antagonist therapy prior to day 3 post-MI.

Discussant Dr John McMurray, professor of cardiology at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, said that ALBATROSS was simply underpowered and thus leaves unanswered the clinically important question of whether early initiation of aldosterone blockade post MI in patients without heart failure confers clinical benefit. The investigators projected a total of 269 events in the composite endpoint but got only 194 because the study participants were so well treated and contemporary medical and interventional therapies are quite effective.

He dismissed the sharp reduction seen in 6-month mortality with spironolactone in the STEMI patients as “just implausible—we don’t know of any treatments in medicine that reduce mortality by 80%.”

Noting that there were only 28 deaths in the study, Dr McMurray asserted that “a subgroup analysis on such a small number of events is never going to give you a reliable result.” Moreover, he added, “subgroup analysis is even more treacherous when the overall trial is underpowered.”

Dr Montalescot replied that, while he considers the signal of a mortality benefit for aldosterone blockade in STEMI patients worthy of pursuit in a large randomized trial, the prospects for mounting such a study are poor. The medications are now available as generics, so there is no commercial incentive. The French Ministry of Health, which funded ALBATROSS, isn’t prepared to back a follow-up study. The best hope is that eventually one of the pharmaceutical companies developing third-generation aldosterone antagonists, now in phase II studies, will become interested, he said.

Dr Montalescot said that, while he receives research grants and consulting fees from numerous pharmaceutical companies, these commercial relationships aren’t relevant to the government-funded ALBATROSS trial.

Inpatient Mortality Down for High-Volume Conditions

BY RICHARD FRANKI

Frontline Medical News

Over that period, mortality among adults hospitalized with pneumonia went from 65 per 1,000 admissions to 35.8 per 1,000 for a drop of 45%—the largest of the four high-volume conditions. Corresponding declines for the others were 41% for acute MI, 29% for heart failure, and 27% for stroke, the AHRQ noted.

Since “death following discharge from a hospital is not reflected in these data,” the report said, measures of inpatient mortality “can reflect both improvements in health care and shifts in where end-of-life care takes place over time.”

The estimates in the report are based on data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (2002-2011) and State Inpatient Databases (2012).1

- Timely Epinephrine for Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

- Andersen LW, Berg, KM, Saindon BZ, et al; American Heart Associaton Get With the Guidelines—Resuscitation Investigators. Time to epinephrine and survival after pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2015;314(8):802-810.

- Tasker RC, Randolph AG. Pediatric pulseless arrest with “nonshockable” rhythm: does faster time to epinephrine improve outsome? JAMA. 2015;314(8):776-777.

- ED Care Pathway Hastens Febrile Neutropenia Therapy

- Keng MK, Thallner EA, Elson P, et al. Reducing time to antibiotic administration for febrile neutropenia in the emergency department [published online ahead of print July 28, 2015]. J Oncol Pract.

- ESC: Aldosterone Blockade Fails to Fly for Early MI in ALBATROSS

- Aldosterone Lethal Effects Blocked in AMI Treated With or Without Reperfusion to Improve Outcome and Survival at Six Months Follow-up: THE ALBATROSS TRIAL. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2015 September 14. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01059136.

- Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, et al; Eplerenon Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study Investigators. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(14)1309-1321.

- Inpatient Mortality Down for High-Volume Conditions

- Statistical Brief #194. Trends in Observed Adult Inpatient Mortality for High-Volume Conditions, 2002-2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). July 2015. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb194-Inpatient-Mortality-High-Volume-Conditions.jsp. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- Timely Epinephrine for Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

- Andersen LW, Berg, KM, Saindon BZ, et al; American Heart Associaton Get With the Guidelines—Resuscitation Investigators. Time to epinephrine and survival after pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2015;314(8):802-810.

- Tasker RC, Randolph AG. Pediatric pulseless arrest with “nonshockable” rhythm: does faster time to epinephrine improve outsome? JAMA. 2015;314(8):776-777.

- ED Care Pathway Hastens Febrile Neutropenia Therapy

- Keng MK, Thallner EA, Elson P, et al. Reducing time to antibiotic administration for febrile neutropenia in the emergency department [published online ahead of print July 28, 2015]. J Oncol Pract.

- ESC: Aldosterone Blockade Fails to Fly for Early MI in ALBATROSS

- Aldosterone Lethal Effects Blocked in AMI Treated With or Without Reperfusion to Improve Outcome and Survival at Six Months Follow-up: THE ALBATROSS TRIAL. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2015 September 14. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01059136.

- Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, et al; Eplerenon Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study Investigators. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(14)1309-1321.

- Inpatient Mortality Down for High-Volume Conditions

- Statistical Brief #194. Trends in Observed Adult Inpatient Mortality for High-Volume Conditions, 2002-2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). July 2015. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb194-Inpatient-Mortality-High-Volume-Conditions.jsp. Accessed August 20, 2015.