User login

CASE Alice D is 20 years old and has type 1 diabetes, as well as retinopathy, hypertension, bipolar I disorder, and hyperlipidemia. She is a new patient at your clinic and reports that she is “occasionally homeless” and has difficulty affording food.

You renew Ms. D’s prescriptions during the visit, discuss nutrition with her, and

According to a 2016 report from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service, an estimated 12.3% of households in the United States are “food insecure.”1 To ascertain what food security and insecurity are, the USDA measured numerous variables, including household structure, race and ethnicity, geography, and income. The report of the Economic Research Service stands as one of the largest domestic sources of information about food insecurity.

Food insecurity is defined as “food intake of household members [that is] reduced and normal eating patterns that are disrupted.”1 It is often measured “per household,” but those data must be interpreted carefully because food insecurity affects household members differently. Some members, such as children, might be affected only mildly; adults, on the other hand, might be more severely affected. (Adults may, for instance, disrupt or skip their meals to maintain normal diets and meal patterns for their children.) In some households, food insecurity affects only a single member—such as an older adult—because of conditions unique to the people living in the home.

In this article, we review variables that can give rise to food insecurity in children, adults, and the elderly, and offer strategies to the family physician for identifying and alleviating the burden of food insecurity in these populations.

Food insecurity threatens children’s health, development

In 2016, households with children faced a higher level of food insecurity (16.5%) than the national average (12.3%).1 In a study of more than 280,000 households, food insecurity was sometimes so severe that children skipped meals or did not eat for the whole day.1 Although income strongly correlates with food insecurity, evidence shows that families above and below the poverty line suffer from food insecurity.2,3

According to the USDA, the rate of food insecurity is higher than the national average of 12.3% in several subgroups of children1:

- households with children < 6 years of age (16.6%)

- households with children headed by a single woman (31.6%) or single man (21.7%)

- households headed by a black non-Hispanic (22.5%) or Hispanic (18.5%) person

- low-income households in which the annual income is < 185% of the poverty threshold (31.6%).

Continue to: Evidence suggests that...

Evidence suggests that children in food-insecure homes experience poor diet, impaired cognitive development, an increased risk of chronic illness in adulthood, and emotional and behavioral problems.4-7 For caregivers in food-insecure homes, purchase price is the most influential factor when making food purchasing decisions. Thus, caregivers often purchase cheaper, more calorie-dense foods, rather than more expensive, nutrient-rich foods—leading to childhood obesity.8

Relief eludes many. Federal programs, such as the National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, the Summer Food Service Program, and the Child and Adult Care Food Program, provide free or reduced-price meals for school-age children. Although these programs reduce food insecurity in households that participate, program policy has established that participation is based on household income.9 This is problematic: According to the literature,2 the income of 50% of households that are food-insecure is above the federal poverty level.

It would be more effective to have these programs target families based on geography, not income, because programs would then benefit those who are food-insecure but who live above the poverty line. Location is a significant factor in identifying food-insecure populations: Households outside metropolitan areas are disproportionately affected.1 If these programs were to privilege geography over income, they would include (for example): families in school districts with a low number of grocery stores; families with poor access to public transportation; and families that live in a “food desert”—ie, where fresh, low-cost food options are overshadowed by fast food.

One such program closely applied the model of privilege based on geography: In 2010, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act was passed, with a Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) that funded school districts in which ≥ 40% of students lived below the poverty line, so that students in those districts received a free school lunch.10 Although eligibility for CEP is still based on income, benefits go to all students who live in the district, including food-insecure students who live in a household above the poverty line. If eligibility criteria were expanded with CEP so that more school districts could participate, it might solve many obstacles faced by other existing programs.

Programs that provide nutrition for households with an infant or young child—eg, the Women, Infants and Children Special Supplemental Nutrition Program (WIC) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—reduce food insecurity in households by 20%. However, several unstudied factors can affect food insecurity in families beyond these programs11; some assumptions about food insecurity, for example, strongly point to the influence of maternal mental health.12

Continue to: Data from the...

Data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort showed that mothers (with an infant) who were suffering from depression had a significantly increased risk of food insecurity.13 To better identify infants at risk of food insecurity, it would be beneficial to identify women suffering from depression during pregnancy or postpartum.13 These patients could then be referred to WIC and for SNAP benefits.

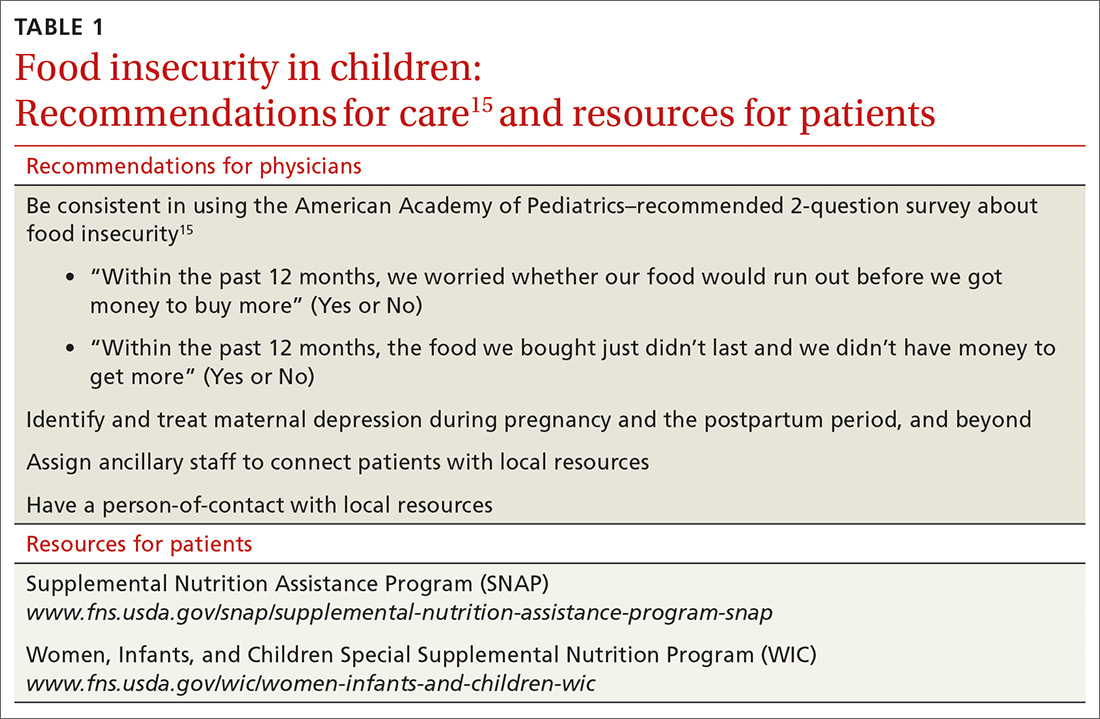

What you can do. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that physicians identify families that are food-insecure by conducting a validated14 2-question survey about food insecurity at every health-maintenance visit, as long as the child is a patient in the practice (TABLE 1).15 Physicians can then refer families that screen positively to local WIC and SNAP centers.

Ideally, physicians should be prepared to facilitate more active engagement by providing patients with the contact information of staff members working in such local programs. Staffing the practice with a patient-care manager can be an efficient way to navigate this process.

CASE Over the 6 weeks following Ms. D’s visit with you, she is admitted 5 times to the hospital in diabetic ketoacidosis, always with a significantly elevated blood glucose level. At each admission, she admits to “sometimes forgetting” to take insulin. Hospital staff members do not ask about her food intake. During each hospitalization, Ms. D is treated with insulin and intravenous fluids and discharged to home on her prior insulin regimen.

During a follow-up appointment with you and the clinic’s nurse–care manager, she talks about missing doses of insulin. She tells you that she has been getting food from the local food pantry, where available stocks are typically carbohydrate-based, including bread, rice, and cereal. She admits that she cannot afford other kinds of food—specifically, those that contain protein and monosaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

Continue to: Adults...

Adults: Poor financial health correlates with insecurity

The correlation between food insecurity and income is strong—evidenced by the spike in the number of adults who reported food insecurity during the 2008-2011 recession in the United States, to a high of 14.9%.1 As noted, households with children are more likely to report food insecurity. In addition, studies show that limited resources, race and ethnicity, underemployment or unemployment, and high housing costs are also strongly associated with food insecurity.16 Even subtle economic fluctuations—for example, an increase in the price of gasoline, natural gas, or electricity—contribute to food insecurity.17 Debt and coping mechanisms influence whether a household living below the poverty line is food-secure or food-insecure. Additional factors contributing to food insecurity include participation in SNAP, education, and severe depression.

Food insecurity in adults reduces the quality of food and nutritional intake, and is associated with chronic morbidity, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.5-7 Adults in food-insecure homes are more likely to purchase cheap, calorie-dense, nutritionally poor foods (or refrain from purchasing food altogether, to pay other debts).17,18 The literature further suggests that food insecurity is associated with diseases that limit function and lead to disability, such as arthritis, stroke, and coronary artery disease, in adults and older adults (> 65 years of age; see the next section).5,6,19 These studies are weak, however, in their ability to show directionality: Does food insecurity cause disability or does disability cause food insecurity?

Patchwork of programs. Programs such as WIC are available for women who are pregnant or have children < 5 years of age. Federal programs for adults who do not have children are scarce, however, and the burden of food insecurity for this population is typically addressed by local programs, such as food banks and food kitchens. Evidence shows that (1) combining the efforts of federal and local food programs is the most effective method of stymieing food insecurity in adults and (2) it would benefit food-insecure adults to have access to such programs. Regrettably, many food programs are underutilized because of barriers that include poor outreach, ineffectual application, and ineligibility.

What you can do. Although it might not be an official, professional society guideline to include questions about food security in a patient wellness survey, physicians should consider creating one for their practice that they (or the office staff) can administer. Furthermore, physicians (or, again, the office staff) should familiarize themselves with programs in the community, such as SNAP or a food bank, to which they can refer patients, as needed.

CASE You ask the nurse–care manager to consult with staff of the food bank and request that, based on your evaluation and recommendation, Ms. D be given more protein-based foods, including peanut butter and beans, when she visits the food bank. The nurse–care manager also makes arrangements to procure an insulin pump for Ms. D.

Continue to: In a short time...

In a short time, Ms. D’s blood glucose level normalizes. She has no further admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis.

Older adults: Interplay of risk factors takes a toll

The USDA Economic Research Report on food insecurity1 states that older adults (≥ 65 years of age) report a lower rate of food insecurity—ie, 7.8% of households with an older adult and 8.9% of households in which the older adult lives alone—compared with the national average.1 The report is limited, however, in its ability to extrapolate data from older adults on food insecurity because its focus is on factors specific to adults and children.

Factors that contribute to food insecurity in the elderly include race and ethnicity, education, income, being a SNAP recipient, and severe depression.1,2,17,20,21 Older adult subgroups more likely to be food-insecure are Hispanic and black non-Hispanic—both significantly associated with being food-insecure, with Hispanic populations reporting the highest rates of food insecurity.20,21 This is a particularly interesting observation: Many traditional Hispanic homes are multigenerational and maintain a culture in which older adults are cared for by their children; that value system might be an indication of why many Hispanic households are disproportionately affected by food insecurity.

Other problems directly caused or exacerbated by food insecurity in the older population include a higher risk of malnutrition from periodontal disease, more frequent hospital admissions with longer length of stay, and an increased rate of falls and fractures. Polypharmacy, which can cause food–drug interactions that inhibit uptake of vitamins or create a higher demand for certain vitamins, is a noteworthy problem associated with food insecurity.

Problems with functionality might prevent older adults from performing physical tasks, such as shopping and preparing foods.21,22 Older adults who reported functional impairment in performing activities of daily living are more likely to report food insecurity.21,22 Last,older adults who live alone are more likely to have diminished nutritional intake than those who live with a spouse or partner.2,22,23

Continue to: Legislation enacted in 2010...

Legislation enacted in 2010 under the existing Older Americans Act provided home-delivered meals, nutritional screening, and education counseling to Americans > 60 years of age. That provision was not based on an income test, however, and served only 18% of the older population.23 (Other programs, such as SNAP, are utilized to a greater degree: 30% of eligible older adults participate, 75% of whom live alone.23) Possible reasons for underutilization include restricted funding, lower education level, lack of outreach, a confusing application process, and the impression that the process is intrusive.24-26

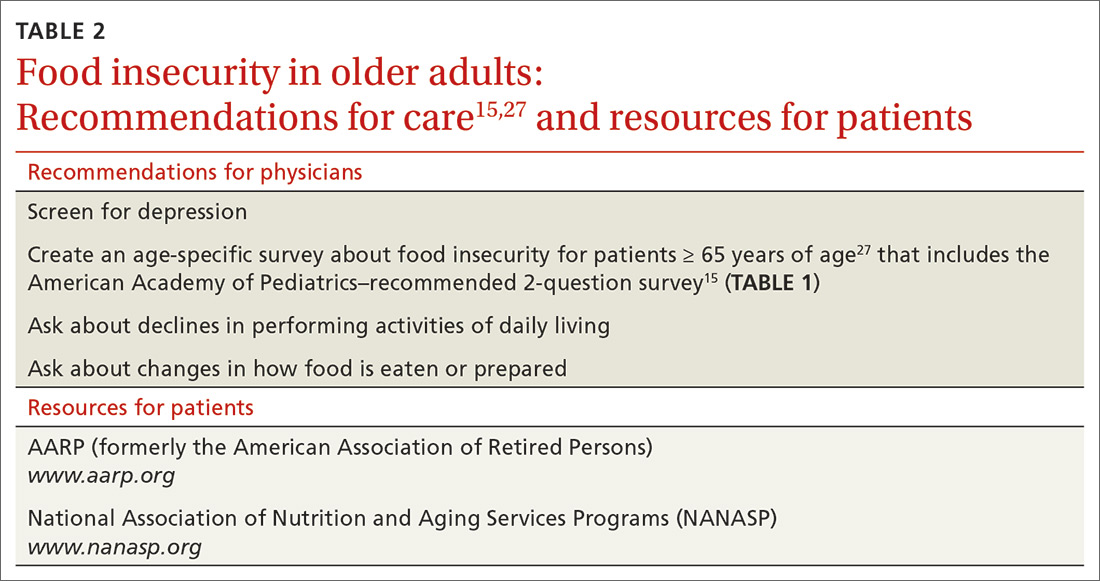

What you can do. To improve the nutritional intake of older adults, reconcile the patient’s medications at each visit to ensure that polypharmacy does not play a role in causing or exacerbating underlying conditions that can lead to poor nutritional intake. AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons) recommends devising and conducting a survey of food insecurity with older adults that includes the 2-question American Academy of Pediatrics survey described earlier27 (TABLE 215,27).Such a survey, which can be administered by office staff, should also include a screen for depression, financial stability, ability to perform activities of daily living (eg, shopping and driving), and changes in diet that are a result of periodontal disease. The survey should also inquire about the effects of current or chronic disability on day-to-day life.

For all patients: Refer to community resources

The problems of food insecurity presented here only broadly address what each of these 3 groups face. Although the overall trend in food insecurity has been downward since 2011, deeper issues of food insecurity need to be studied more within each population. This is particularly true among the geriatric population, whose numbers are increasing, and among ethnic minorities, including black non-Hispanics, and Hispanics, who face additional daily stressors because of implicit biases in society.

More study is needed to decrease the rate of food insecurity across all populations in the United States. In the interim, family physicians should take advantage of their role in the care of families, children, and older people to address the problem of food insecurity in their patient population by applying the interventions we’ve outlined, with an emphasis on referral to resources in the community.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lillian Amèzquita, BS, The Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Box G-9999, 222 Richmond Street, Providence, RI; lillian_amezquita@brown.edu.

1. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, et al. Household Food Security in the United States in 2016, ERR-237. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; September 2017. www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84973/err-237.pdf?v=0. Accessed January 10, 2019.

2. Rose D. Economic determinants and dietary consequences of food insecurity in the United States. J Nutr. 1999;129:517S-520S.

3. Gundersen C. Dynamic determinants of food insecurity. In: Andrews MS, Prell MA, eds. Second Food Security Measurement and Research Conference, Volume II: Papers. [Food Assistance and Nutrition Research Report 11-2.] Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; August 24, 2001:92-110.

4. Kaiser LL, Townsend MS. Food insecurity among US children: implications for nutrition and health. Top Clin Nutr. 2005;20:313-320.

5. Nguyen BT, Shuval K, Bertmann F, et al. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, food insecurity, dietary quality, and obesity among US adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1453-1459.

6. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140:304-310.

7. Laraia BA. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:203-212.

8. Nackers LM, Appelhans BM. Food insecurity is linked to a food environment promoting obesity in households with children. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45:780-784.

9. Ralston K, Treen K, Coleman-Jensen A, et al. Children’s food security and USDA child nutrition programs. Economic Information Bulletin 174. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. June 2017. www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84003/eib-174.pdf?v=0. Accessed January 10, 2020.

10. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. National School Lunch Program: community eligibility provision. April 19, 2019. www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/community-eligibility-provision. Accessed January 10, 2020.

11. Kreider B, Pepper JV, Roy M. Identifying the effects of WIC on food insecurity among infants and children. South Econ J. 2016;82:1106-1122.

12. Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, et al. Influence of maternal depression on household food insecurity for low-income families. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:305-310.

13. Noonan K, Corman H, Reichman NE. Effects of maternal depression on family food insecurity. Econ Hum Biol. 2016;22:201-215.

14. Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e26-e32.

15. American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Community Pediatrics and Committee on Nutrition. Promoting food security for all children. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1431-e1438.

16. Hamelin AM, Habicht JP, Beaudry M. Food insecurity: consequences for the household and broader social implications. J Nutr. 1999;129:525S-528S.

17. Gundersen C, Engelhard E, Hake M. The determinants of food insecurity among food bank clients in the United States. J Consum Aff. 2017;51:501-518.

18. Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:6-9.

19. Venci BJ, Lee S-Y. Functional limitation and chronic diseases are associated with food insecurity among U.S. adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:182-188.

20. Goldberg S, Mawn B. Predictors of food insecurity among older adults in the United States. Public Health Nurs. 2015;32:397-407.

21. Lee JS, Frongillo EA. Factors associated with food insecurity among U.S. elderly persons: importance of functional impairments. J Gerontol. 2001;56B:S94-S99.

22. Chang Y, Hickman H. Food insecurity and perceived diet quality among low-income older Americans with functional limitations. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50:476-484.

23. Kamp B, Wellman N, Russell C. Position of the American Dietetic Association, American Society for Nutrition, and Society for Nutrition Education: Food and nutrition programs for community-residing older adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42:72-82.

24. Cody S, Ohls JC. Evaluation of the US Department of Agriculture Elderly Nutrition Demonstration: Volume I, Evaluation Findings. Contractor and Cooperator Report No. 9-1. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture; July 2005.

25. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; Office of Analysis, Nutrition, and Evaluation. Food stamp participation rates and benefits: an analysis of variation within demographic groups. May 2003. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/PartDemoGroup.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020.

26. Russell JC, Flood VM, Yeatman H, et al. Food insecurity and poor diet quality are associated with reduced quality of life in older adults. Nutr Diet. 2016;73:50-58.

27. Pooler J, Levin M, Hoffman V, et al; AARP Foundation and IMPAQ International. Implementing food security screening and referral for older patients in primary care: a resource guide and toolkit. November 2016. www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/aarp_foundation/2016-pdfs/FoodSecurityScreening.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020.

CASE Alice D is 20 years old and has type 1 diabetes, as well as retinopathy, hypertension, bipolar I disorder, and hyperlipidemia. She is a new patient at your clinic and reports that she is “occasionally homeless” and has difficulty affording food.

You renew Ms. D’s prescriptions during the visit, discuss nutrition with her, and

According to a 2016 report from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service, an estimated 12.3% of households in the United States are “food insecure.”1 To ascertain what food security and insecurity are, the USDA measured numerous variables, including household structure, race and ethnicity, geography, and income. The report of the Economic Research Service stands as one of the largest domestic sources of information about food insecurity.

Food insecurity is defined as “food intake of household members [that is] reduced and normal eating patterns that are disrupted.”1 It is often measured “per household,” but those data must be interpreted carefully because food insecurity affects household members differently. Some members, such as children, might be affected only mildly; adults, on the other hand, might be more severely affected. (Adults may, for instance, disrupt or skip their meals to maintain normal diets and meal patterns for their children.) In some households, food insecurity affects only a single member—such as an older adult—because of conditions unique to the people living in the home.

In this article, we review variables that can give rise to food insecurity in children, adults, and the elderly, and offer strategies to the family physician for identifying and alleviating the burden of food insecurity in these populations.

Food insecurity threatens children’s health, development

In 2016, households with children faced a higher level of food insecurity (16.5%) than the national average (12.3%).1 In a study of more than 280,000 households, food insecurity was sometimes so severe that children skipped meals or did not eat for the whole day.1 Although income strongly correlates with food insecurity, evidence shows that families above and below the poverty line suffer from food insecurity.2,3

According to the USDA, the rate of food insecurity is higher than the national average of 12.3% in several subgroups of children1:

- households with children < 6 years of age (16.6%)

- households with children headed by a single woman (31.6%) or single man (21.7%)

- households headed by a black non-Hispanic (22.5%) or Hispanic (18.5%) person

- low-income households in which the annual income is < 185% of the poverty threshold (31.6%).

Continue to: Evidence suggests that...

Evidence suggests that children in food-insecure homes experience poor diet, impaired cognitive development, an increased risk of chronic illness in adulthood, and emotional and behavioral problems.4-7 For caregivers in food-insecure homes, purchase price is the most influential factor when making food purchasing decisions. Thus, caregivers often purchase cheaper, more calorie-dense foods, rather than more expensive, nutrient-rich foods—leading to childhood obesity.8

Relief eludes many. Federal programs, such as the National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, the Summer Food Service Program, and the Child and Adult Care Food Program, provide free or reduced-price meals for school-age children. Although these programs reduce food insecurity in households that participate, program policy has established that participation is based on household income.9 This is problematic: According to the literature,2 the income of 50% of households that are food-insecure is above the federal poverty level.

It would be more effective to have these programs target families based on geography, not income, because programs would then benefit those who are food-insecure but who live above the poverty line. Location is a significant factor in identifying food-insecure populations: Households outside metropolitan areas are disproportionately affected.1 If these programs were to privilege geography over income, they would include (for example): families in school districts with a low number of grocery stores; families with poor access to public transportation; and families that live in a “food desert”—ie, where fresh, low-cost food options are overshadowed by fast food.

One such program closely applied the model of privilege based on geography: In 2010, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act was passed, with a Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) that funded school districts in which ≥ 40% of students lived below the poverty line, so that students in those districts received a free school lunch.10 Although eligibility for CEP is still based on income, benefits go to all students who live in the district, including food-insecure students who live in a household above the poverty line. If eligibility criteria were expanded with CEP so that more school districts could participate, it might solve many obstacles faced by other existing programs.

Programs that provide nutrition for households with an infant or young child—eg, the Women, Infants and Children Special Supplemental Nutrition Program (WIC) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—reduce food insecurity in households by 20%. However, several unstudied factors can affect food insecurity in families beyond these programs11; some assumptions about food insecurity, for example, strongly point to the influence of maternal mental health.12

Continue to: Data from the...

Data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort showed that mothers (with an infant) who were suffering from depression had a significantly increased risk of food insecurity.13 To better identify infants at risk of food insecurity, it would be beneficial to identify women suffering from depression during pregnancy or postpartum.13 These patients could then be referred to WIC and for SNAP benefits.

What you can do. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that physicians identify families that are food-insecure by conducting a validated14 2-question survey about food insecurity at every health-maintenance visit, as long as the child is a patient in the practice (TABLE 1).15 Physicians can then refer families that screen positively to local WIC and SNAP centers.

Ideally, physicians should be prepared to facilitate more active engagement by providing patients with the contact information of staff members working in such local programs. Staffing the practice with a patient-care manager can be an efficient way to navigate this process.

CASE Over the 6 weeks following Ms. D’s visit with you, she is admitted 5 times to the hospital in diabetic ketoacidosis, always with a significantly elevated blood glucose level. At each admission, she admits to “sometimes forgetting” to take insulin. Hospital staff members do not ask about her food intake. During each hospitalization, Ms. D is treated with insulin and intravenous fluids and discharged to home on her prior insulin regimen.

During a follow-up appointment with you and the clinic’s nurse–care manager, she talks about missing doses of insulin. She tells you that she has been getting food from the local food pantry, where available stocks are typically carbohydrate-based, including bread, rice, and cereal. She admits that she cannot afford other kinds of food—specifically, those that contain protein and monosaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

Continue to: Adults...

Adults: Poor financial health correlates with insecurity

The correlation between food insecurity and income is strong—evidenced by the spike in the number of adults who reported food insecurity during the 2008-2011 recession in the United States, to a high of 14.9%.1 As noted, households with children are more likely to report food insecurity. In addition, studies show that limited resources, race and ethnicity, underemployment or unemployment, and high housing costs are also strongly associated with food insecurity.16 Even subtle economic fluctuations—for example, an increase in the price of gasoline, natural gas, or electricity—contribute to food insecurity.17 Debt and coping mechanisms influence whether a household living below the poverty line is food-secure or food-insecure. Additional factors contributing to food insecurity include participation in SNAP, education, and severe depression.

Food insecurity in adults reduces the quality of food and nutritional intake, and is associated with chronic morbidity, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.5-7 Adults in food-insecure homes are more likely to purchase cheap, calorie-dense, nutritionally poor foods (or refrain from purchasing food altogether, to pay other debts).17,18 The literature further suggests that food insecurity is associated with diseases that limit function and lead to disability, such as arthritis, stroke, and coronary artery disease, in adults and older adults (> 65 years of age; see the next section).5,6,19 These studies are weak, however, in their ability to show directionality: Does food insecurity cause disability or does disability cause food insecurity?

Patchwork of programs. Programs such as WIC are available for women who are pregnant or have children < 5 years of age. Federal programs for adults who do not have children are scarce, however, and the burden of food insecurity for this population is typically addressed by local programs, such as food banks and food kitchens. Evidence shows that (1) combining the efforts of federal and local food programs is the most effective method of stymieing food insecurity in adults and (2) it would benefit food-insecure adults to have access to such programs. Regrettably, many food programs are underutilized because of barriers that include poor outreach, ineffectual application, and ineligibility.

What you can do. Although it might not be an official, professional society guideline to include questions about food security in a patient wellness survey, physicians should consider creating one for their practice that they (or the office staff) can administer. Furthermore, physicians (or, again, the office staff) should familiarize themselves with programs in the community, such as SNAP or a food bank, to which they can refer patients, as needed.

CASE You ask the nurse–care manager to consult with staff of the food bank and request that, based on your evaluation and recommendation, Ms. D be given more protein-based foods, including peanut butter and beans, when she visits the food bank. The nurse–care manager also makes arrangements to procure an insulin pump for Ms. D.

Continue to: In a short time...

In a short time, Ms. D’s blood glucose level normalizes. She has no further admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis.

Older adults: Interplay of risk factors takes a toll

The USDA Economic Research Report on food insecurity1 states that older adults (≥ 65 years of age) report a lower rate of food insecurity—ie, 7.8% of households with an older adult and 8.9% of households in which the older adult lives alone—compared with the national average.1 The report is limited, however, in its ability to extrapolate data from older adults on food insecurity because its focus is on factors specific to adults and children.

Factors that contribute to food insecurity in the elderly include race and ethnicity, education, income, being a SNAP recipient, and severe depression.1,2,17,20,21 Older adult subgroups more likely to be food-insecure are Hispanic and black non-Hispanic—both significantly associated with being food-insecure, with Hispanic populations reporting the highest rates of food insecurity.20,21 This is a particularly interesting observation: Many traditional Hispanic homes are multigenerational and maintain a culture in which older adults are cared for by their children; that value system might be an indication of why many Hispanic households are disproportionately affected by food insecurity.

Other problems directly caused or exacerbated by food insecurity in the older population include a higher risk of malnutrition from periodontal disease, more frequent hospital admissions with longer length of stay, and an increased rate of falls and fractures. Polypharmacy, which can cause food–drug interactions that inhibit uptake of vitamins or create a higher demand for certain vitamins, is a noteworthy problem associated with food insecurity.

Problems with functionality might prevent older adults from performing physical tasks, such as shopping and preparing foods.21,22 Older adults who reported functional impairment in performing activities of daily living are more likely to report food insecurity.21,22 Last,older adults who live alone are more likely to have diminished nutritional intake than those who live with a spouse or partner.2,22,23

Continue to: Legislation enacted in 2010...

Legislation enacted in 2010 under the existing Older Americans Act provided home-delivered meals, nutritional screening, and education counseling to Americans > 60 years of age. That provision was not based on an income test, however, and served only 18% of the older population.23 (Other programs, such as SNAP, are utilized to a greater degree: 30% of eligible older adults participate, 75% of whom live alone.23) Possible reasons for underutilization include restricted funding, lower education level, lack of outreach, a confusing application process, and the impression that the process is intrusive.24-26

What you can do. To improve the nutritional intake of older adults, reconcile the patient’s medications at each visit to ensure that polypharmacy does not play a role in causing or exacerbating underlying conditions that can lead to poor nutritional intake. AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons) recommends devising and conducting a survey of food insecurity with older adults that includes the 2-question American Academy of Pediatrics survey described earlier27 (TABLE 215,27).Such a survey, which can be administered by office staff, should also include a screen for depression, financial stability, ability to perform activities of daily living (eg, shopping and driving), and changes in diet that are a result of periodontal disease. The survey should also inquire about the effects of current or chronic disability on day-to-day life.

For all patients: Refer to community resources

The problems of food insecurity presented here only broadly address what each of these 3 groups face. Although the overall trend in food insecurity has been downward since 2011, deeper issues of food insecurity need to be studied more within each population. This is particularly true among the geriatric population, whose numbers are increasing, and among ethnic minorities, including black non-Hispanics, and Hispanics, who face additional daily stressors because of implicit biases in society.

More study is needed to decrease the rate of food insecurity across all populations in the United States. In the interim, family physicians should take advantage of their role in the care of families, children, and older people to address the problem of food insecurity in their patient population by applying the interventions we’ve outlined, with an emphasis on referral to resources in the community.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lillian Amèzquita, BS, The Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Box G-9999, 222 Richmond Street, Providence, RI; lillian_amezquita@brown.edu.

CASE Alice D is 20 years old and has type 1 diabetes, as well as retinopathy, hypertension, bipolar I disorder, and hyperlipidemia. She is a new patient at your clinic and reports that she is “occasionally homeless” and has difficulty affording food.

You renew Ms. D’s prescriptions during the visit, discuss nutrition with her, and

According to a 2016 report from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service, an estimated 12.3% of households in the United States are “food insecure.”1 To ascertain what food security and insecurity are, the USDA measured numerous variables, including household structure, race and ethnicity, geography, and income. The report of the Economic Research Service stands as one of the largest domestic sources of information about food insecurity.

Food insecurity is defined as “food intake of household members [that is] reduced and normal eating patterns that are disrupted.”1 It is often measured “per household,” but those data must be interpreted carefully because food insecurity affects household members differently. Some members, such as children, might be affected only mildly; adults, on the other hand, might be more severely affected. (Adults may, for instance, disrupt or skip their meals to maintain normal diets and meal patterns for their children.) In some households, food insecurity affects only a single member—such as an older adult—because of conditions unique to the people living in the home.

In this article, we review variables that can give rise to food insecurity in children, adults, and the elderly, and offer strategies to the family physician for identifying and alleviating the burden of food insecurity in these populations.

Food insecurity threatens children’s health, development

In 2016, households with children faced a higher level of food insecurity (16.5%) than the national average (12.3%).1 In a study of more than 280,000 households, food insecurity was sometimes so severe that children skipped meals or did not eat for the whole day.1 Although income strongly correlates with food insecurity, evidence shows that families above and below the poverty line suffer from food insecurity.2,3

According to the USDA, the rate of food insecurity is higher than the national average of 12.3% in several subgroups of children1:

- households with children < 6 years of age (16.6%)

- households with children headed by a single woman (31.6%) or single man (21.7%)

- households headed by a black non-Hispanic (22.5%) or Hispanic (18.5%) person

- low-income households in which the annual income is < 185% of the poverty threshold (31.6%).

Continue to: Evidence suggests that...

Evidence suggests that children in food-insecure homes experience poor diet, impaired cognitive development, an increased risk of chronic illness in adulthood, and emotional and behavioral problems.4-7 For caregivers in food-insecure homes, purchase price is the most influential factor when making food purchasing decisions. Thus, caregivers often purchase cheaper, more calorie-dense foods, rather than more expensive, nutrient-rich foods—leading to childhood obesity.8

Relief eludes many. Federal programs, such as the National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, the Summer Food Service Program, and the Child and Adult Care Food Program, provide free or reduced-price meals for school-age children. Although these programs reduce food insecurity in households that participate, program policy has established that participation is based on household income.9 This is problematic: According to the literature,2 the income of 50% of households that are food-insecure is above the federal poverty level.

It would be more effective to have these programs target families based on geography, not income, because programs would then benefit those who are food-insecure but who live above the poverty line. Location is a significant factor in identifying food-insecure populations: Households outside metropolitan areas are disproportionately affected.1 If these programs were to privilege geography over income, they would include (for example): families in school districts with a low number of grocery stores; families with poor access to public transportation; and families that live in a “food desert”—ie, where fresh, low-cost food options are overshadowed by fast food.

One such program closely applied the model of privilege based on geography: In 2010, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act was passed, with a Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) that funded school districts in which ≥ 40% of students lived below the poverty line, so that students in those districts received a free school lunch.10 Although eligibility for CEP is still based on income, benefits go to all students who live in the district, including food-insecure students who live in a household above the poverty line. If eligibility criteria were expanded with CEP so that more school districts could participate, it might solve many obstacles faced by other existing programs.

Programs that provide nutrition for households with an infant or young child—eg, the Women, Infants and Children Special Supplemental Nutrition Program (WIC) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—reduce food insecurity in households by 20%. However, several unstudied factors can affect food insecurity in families beyond these programs11; some assumptions about food insecurity, for example, strongly point to the influence of maternal mental health.12

Continue to: Data from the...

Data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort showed that mothers (with an infant) who were suffering from depression had a significantly increased risk of food insecurity.13 To better identify infants at risk of food insecurity, it would be beneficial to identify women suffering from depression during pregnancy or postpartum.13 These patients could then be referred to WIC and for SNAP benefits.

What you can do. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that physicians identify families that are food-insecure by conducting a validated14 2-question survey about food insecurity at every health-maintenance visit, as long as the child is a patient in the practice (TABLE 1).15 Physicians can then refer families that screen positively to local WIC and SNAP centers.

Ideally, physicians should be prepared to facilitate more active engagement by providing patients with the contact information of staff members working in such local programs. Staffing the practice with a patient-care manager can be an efficient way to navigate this process.

CASE Over the 6 weeks following Ms. D’s visit with you, she is admitted 5 times to the hospital in diabetic ketoacidosis, always with a significantly elevated blood glucose level. At each admission, she admits to “sometimes forgetting” to take insulin. Hospital staff members do not ask about her food intake. During each hospitalization, Ms. D is treated with insulin and intravenous fluids and discharged to home on her prior insulin regimen.

During a follow-up appointment with you and the clinic’s nurse–care manager, she talks about missing doses of insulin. She tells you that she has been getting food from the local food pantry, where available stocks are typically carbohydrate-based, including bread, rice, and cereal. She admits that she cannot afford other kinds of food—specifically, those that contain protein and monosaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

Continue to: Adults...

Adults: Poor financial health correlates with insecurity

The correlation between food insecurity and income is strong—evidenced by the spike in the number of adults who reported food insecurity during the 2008-2011 recession in the United States, to a high of 14.9%.1 As noted, households with children are more likely to report food insecurity. In addition, studies show that limited resources, race and ethnicity, underemployment or unemployment, and high housing costs are also strongly associated with food insecurity.16 Even subtle economic fluctuations—for example, an increase in the price of gasoline, natural gas, or electricity—contribute to food insecurity.17 Debt and coping mechanisms influence whether a household living below the poverty line is food-secure or food-insecure. Additional factors contributing to food insecurity include participation in SNAP, education, and severe depression.

Food insecurity in adults reduces the quality of food and nutritional intake, and is associated with chronic morbidity, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.5-7 Adults in food-insecure homes are more likely to purchase cheap, calorie-dense, nutritionally poor foods (or refrain from purchasing food altogether, to pay other debts).17,18 The literature further suggests that food insecurity is associated with diseases that limit function and lead to disability, such as arthritis, stroke, and coronary artery disease, in adults and older adults (> 65 years of age; see the next section).5,6,19 These studies are weak, however, in their ability to show directionality: Does food insecurity cause disability or does disability cause food insecurity?

Patchwork of programs. Programs such as WIC are available for women who are pregnant or have children < 5 years of age. Federal programs for adults who do not have children are scarce, however, and the burden of food insecurity for this population is typically addressed by local programs, such as food banks and food kitchens. Evidence shows that (1) combining the efforts of federal and local food programs is the most effective method of stymieing food insecurity in adults and (2) it would benefit food-insecure adults to have access to such programs. Regrettably, many food programs are underutilized because of barriers that include poor outreach, ineffectual application, and ineligibility.

What you can do. Although it might not be an official, professional society guideline to include questions about food security in a patient wellness survey, physicians should consider creating one for their practice that they (or the office staff) can administer. Furthermore, physicians (or, again, the office staff) should familiarize themselves with programs in the community, such as SNAP or a food bank, to which they can refer patients, as needed.

CASE You ask the nurse–care manager to consult with staff of the food bank and request that, based on your evaluation and recommendation, Ms. D be given more protein-based foods, including peanut butter and beans, when she visits the food bank. The nurse–care manager also makes arrangements to procure an insulin pump for Ms. D.

Continue to: In a short time...

In a short time, Ms. D’s blood glucose level normalizes. She has no further admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis.

Older adults: Interplay of risk factors takes a toll

The USDA Economic Research Report on food insecurity1 states that older adults (≥ 65 years of age) report a lower rate of food insecurity—ie, 7.8% of households with an older adult and 8.9% of households in which the older adult lives alone—compared with the national average.1 The report is limited, however, in its ability to extrapolate data from older adults on food insecurity because its focus is on factors specific to adults and children.

Factors that contribute to food insecurity in the elderly include race and ethnicity, education, income, being a SNAP recipient, and severe depression.1,2,17,20,21 Older adult subgroups more likely to be food-insecure are Hispanic and black non-Hispanic—both significantly associated with being food-insecure, with Hispanic populations reporting the highest rates of food insecurity.20,21 This is a particularly interesting observation: Many traditional Hispanic homes are multigenerational and maintain a culture in which older adults are cared for by their children; that value system might be an indication of why many Hispanic households are disproportionately affected by food insecurity.

Other problems directly caused or exacerbated by food insecurity in the older population include a higher risk of malnutrition from periodontal disease, more frequent hospital admissions with longer length of stay, and an increased rate of falls and fractures. Polypharmacy, which can cause food–drug interactions that inhibit uptake of vitamins or create a higher demand for certain vitamins, is a noteworthy problem associated with food insecurity.

Problems with functionality might prevent older adults from performing physical tasks, such as shopping and preparing foods.21,22 Older adults who reported functional impairment in performing activities of daily living are more likely to report food insecurity.21,22 Last,older adults who live alone are more likely to have diminished nutritional intake than those who live with a spouse or partner.2,22,23

Continue to: Legislation enacted in 2010...

Legislation enacted in 2010 under the existing Older Americans Act provided home-delivered meals, nutritional screening, and education counseling to Americans > 60 years of age. That provision was not based on an income test, however, and served only 18% of the older population.23 (Other programs, such as SNAP, are utilized to a greater degree: 30% of eligible older adults participate, 75% of whom live alone.23) Possible reasons for underutilization include restricted funding, lower education level, lack of outreach, a confusing application process, and the impression that the process is intrusive.24-26

What you can do. To improve the nutritional intake of older adults, reconcile the patient’s medications at each visit to ensure that polypharmacy does not play a role in causing or exacerbating underlying conditions that can lead to poor nutritional intake. AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons) recommends devising and conducting a survey of food insecurity with older adults that includes the 2-question American Academy of Pediatrics survey described earlier27 (TABLE 215,27).Such a survey, which can be administered by office staff, should also include a screen for depression, financial stability, ability to perform activities of daily living (eg, shopping and driving), and changes in diet that are a result of periodontal disease. The survey should also inquire about the effects of current or chronic disability on day-to-day life.

For all patients: Refer to community resources

The problems of food insecurity presented here only broadly address what each of these 3 groups face. Although the overall trend in food insecurity has been downward since 2011, deeper issues of food insecurity need to be studied more within each population. This is particularly true among the geriatric population, whose numbers are increasing, and among ethnic minorities, including black non-Hispanics, and Hispanics, who face additional daily stressors because of implicit biases in society.

More study is needed to decrease the rate of food insecurity across all populations in the United States. In the interim, family physicians should take advantage of their role in the care of families, children, and older people to address the problem of food insecurity in their patient population by applying the interventions we’ve outlined, with an emphasis on referral to resources in the community.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lillian Amèzquita, BS, The Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Box G-9999, 222 Richmond Street, Providence, RI; lillian_amezquita@brown.edu.

1. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, et al. Household Food Security in the United States in 2016, ERR-237. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; September 2017. www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84973/err-237.pdf?v=0. Accessed January 10, 2019.

2. Rose D. Economic determinants and dietary consequences of food insecurity in the United States. J Nutr. 1999;129:517S-520S.

3. Gundersen C. Dynamic determinants of food insecurity. In: Andrews MS, Prell MA, eds. Second Food Security Measurement and Research Conference, Volume II: Papers. [Food Assistance and Nutrition Research Report 11-2.] Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; August 24, 2001:92-110.

4. Kaiser LL, Townsend MS. Food insecurity among US children: implications for nutrition and health. Top Clin Nutr. 2005;20:313-320.

5. Nguyen BT, Shuval K, Bertmann F, et al. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, food insecurity, dietary quality, and obesity among US adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1453-1459.

6. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140:304-310.

7. Laraia BA. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:203-212.

8. Nackers LM, Appelhans BM. Food insecurity is linked to a food environment promoting obesity in households with children. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45:780-784.

9. Ralston K, Treen K, Coleman-Jensen A, et al. Children’s food security and USDA child nutrition programs. Economic Information Bulletin 174. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. June 2017. www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84003/eib-174.pdf?v=0. Accessed January 10, 2020.

10. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. National School Lunch Program: community eligibility provision. April 19, 2019. www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/community-eligibility-provision. Accessed January 10, 2020.

11. Kreider B, Pepper JV, Roy M. Identifying the effects of WIC on food insecurity among infants and children. South Econ J. 2016;82:1106-1122.

12. Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, et al. Influence of maternal depression on household food insecurity for low-income families. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:305-310.

13. Noonan K, Corman H, Reichman NE. Effects of maternal depression on family food insecurity. Econ Hum Biol. 2016;22:201-215.

14. Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e26-e32.

15. American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Community Pediatrics and Committee on Nutrition. Promoting food security for all children. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1431-e1438.

16. Hamelin AM, Habicht JP, Beaudry M. Food insecurity: consequences for the household and broader social implications. J Nutr. 1999;129:525S-528S.

17. Gundersen C, Engelhard E, Hake M. The determinants of food insecurity among food bank clients in the United States. J Consum Aff. 2017;51:501-518.

18. Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:6-9.

19. Venci BJ, Lee S-Y. Functional limitation and chronic diseases are associated with food insecurity among U.S. adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:182-188.

20. Goldberg S, Mawn B. Predictors of food insecurity among older adults in the United States. Public Health Nurs. 2015;32:397-407.

21. Lee JS, Frongillo EA. Factors associated with food insecurity among U.S. elderly persons: importance of functional impairments. J Gerontol. 2001;56B:S94-S99.

22. Chang Y, Hickman H. Food insecurity and perceived diet quality among low-income older Americans with functional limitations. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50:476-484.

23. Kamp B, Wellman N, Russell C. Position of the American Dietetic Association, American Society for Nutrition, and Society for Nutrition Education: Food and nutrition programs for community-residing older adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42:72-82.

24. Cody S, Ohls JC. Evaluation of the US Department of Agriculture Elderly Nutrition Demonstration: Volume I, Evaluation Findings. Contractor and Cooperator Report No. 9-1. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture; July 2005.

25. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; Office of Analysis, Nutrition, and Evaluation. Food stamp participation rates and benefits: an analysis of variation within demographic groups. May 2003. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/PartDemoGroup.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020.

26. Russell JC, Flood VM, Yeatman H, et al. Food insecurity and poor diet quality are associated with reduced quality of life in older adults. Nutr Diet. 2016;73:50-58.

27. Pooler J, Levin M, Hoffman V, et al; AARP Foundation and IMPAQ International. Implementing food security screening and referral for older patients in primary care: a resource guide and toolkit. November 2016. www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/aarp_foundation/2016-pdfs/FoodSecurityScreening.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020.

1. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, et al. Household Food Security in the United States in 2016, ERR-237. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; September 2017. www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84973/err-237.pdf?v=0. Accessed January 10, 2019.

2. Rose D. Economic determinants and dietary consequences of food insecurity in the United States. J Nutr. 1999;129:517S-520S.

3. Gundersen C. Dynamic determinants of food insecurity. In: Andrews MS, Prell MA, eds. Second Food Security Measurement and Research Conference, Volume II: Papers. [Food Assistance and Nutrition Research Report 11-2.] Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; August 24, 2001:92-110.

4. Kaiser LL, Townsend MS. Food insecurity among US children: implications for nutrition and health. Top Clin Nutr. 2005;20:313-320.

5. Nguyen BT, Shuval K, Bertmann F, et al. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, food insecurity, dietary quality, and obesity among US adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1453-1459.

6. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140:304-310.

7. Laraia BA. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:203-212.

8. Nackers LM, Appelhans BM. Food insecurity is linked to a food environment promoting obesity in households with children. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45:780-784.

9. Ralston K, Treen K, Coleman-Jensen A, et al. Children’s food security and USDA child nutrition programs. Economic Information Bulletin 174. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. June 2017. www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84003/eib-174.pdf?v=0. Accessed January 10, 2020.

10. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. National School Lunch Program: community eligibility provision. April 19, 2019. www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/community-eligibility-provision. Accessed January 10, 2020.

11. Kreider B, Pepper JV, Roy M. Identifying the effects of WIC on food insecurity among infants and children. South Econ J. 2016;82:1106-1122.

12. Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, et al. Influence of maternal depression on household food insecurity for low-income families. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:305-310.

13. Noonan K, Corman H, Reichman NE. Effects of maternal depression on family food insecurity. Econ Hum Biol. 2016;22:201-215.

14. Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e26-e32.

15. American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Community Pediatrics and Committee on Nutrition. Promoting food security for all children. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1431-e1438.

16. Hamelin AM, Habicht JP, Beaudry M. Food insecurity: consequences for the household and broader social implications. J Nutr. 1999;129:525S-528S.

17. Gundersen C, Engelhard E, Hake M. The determinants of food insecurity among food bank clients in the United States. J Consum Aff. 2017;51:501-518.

18. Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:6-9.

19. Venci BJ, Lee S-Y. Functional limitation and chronic diseases are associated with food insecurity among U.S. adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:182-188.

20. Goldberg S, Mawn B. Predictors of food insecurity among older adults in the United States. Public Health Nurs. 2015;32:397-407.

21. Lee JS, Frongillo EA. Factors associated with food insecurity among U.S. elderly persons: importance of functional impairments. J Gerontol. 2001;56B:S94-S99.

22. Chang Y, Hickman H. Food insecurity and perceived diet quality among low-income older Americans with functional limitations. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50:476-484.

23. Kamp B, Wellman N, Russell C. Position of the American Dietetic Association, American Society for Nutrition, and Society for Nutrition Education: Food and nutrition programs for community-residing older adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42:72-82.

24. Cody S, Ohls JC. Evaluation of the US Department of Agriculture Elderly Nutrition Demonstration: Volume I, Evaluation Findings. Contractor and Cooperator Report No. 9-1. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture; July 2005.

25. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; Office of Analysis, Nutrition, and Evaluation. Food stamp participation rates and benefits: an analysis of variation within demographic groups. May 2003. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/PartDemoGroup.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020.

26. Russell JC, Flood VM, Yeatman H, et al. Food insecurity and poor diet quality are associated with reduced quality of life in older adults. Nutr Diet. 2016;73:50-58.

27. Pooler J, Levin M, Hoffman V, et al; AARP Foundation and IMPAQ International. Implementing food security screening and referral for older patients in primary care: a resource guide and toolkit. November 2016. www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/aarp_foundation/2016-pdfs/FoodSecurityScreening.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consistently use the American Academy of Pediatrics 2-question survey to screen for food insecurity (all populations). A

› Identify and treat maternal depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period, and beyond A and screen for depression in older adults A because depression can reduce motivation to accomplish daily activities, such as obtaining and preparing food.

› Ask older adults about declines in performing activities of daily living C and how food is eaten or prepared . C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series