User login

BOSTON – Eating well may be the best revenge against cognitive decline, a study has shown.

Among 818 dementia-free participants in a longitudinal study of memory and aging, those who adhered to the basic components of the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet had a slower rate of cognitive decline than others who followed more typical American diets, reported Martha Clare Morris, Sc.D., professor and director of the section of nutrition and nutritional epidemiology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

The relationship between diet and cognition was linear, with people who most closely followed the DASH dietary pattern having the slowest rates of decline, Dr. Morris said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

"The individual dietary components that were contributing to this slower decline were higher servings of vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes, and lower intake of total and saturated fats," she said.

The investigators chose to look at dietary patterns because they provide an index of overall dietary quality and incorporate the interactions or synergies that may occur among food groups that constitute a specific pattern.

The DASH diet has been shown to lower blood pressure, increase insulin sensitivity, and reduce weight, serum cholesterol level, inflammation, and oxidative stress.

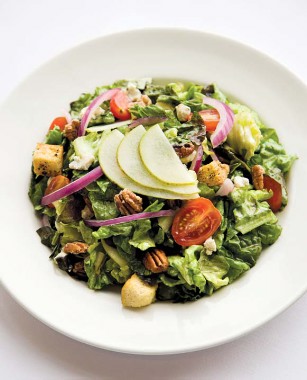

The diet is similar to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern: heavy on fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, lean meats, fish, poultry, and low- or nonfat dairy, and light on sugar and salt.

To see whether a DASH diet pattern could have similarly beneficial effects on cognition and memory, the authors studied 818 adults who participated in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) and who agreed to fill out a 139-item food frequency questionnaire.

MAP enrolled residents from 40 retirement communities who were dementia free at enrollment and who agreed to have annual cognitive and motor tests and blood draws. Participants also agreed to donate their brains, spinal cords, muscles, and nerve tissue at death.

Participants were tested at baseline and annually with a summary measure of 19 tests assessing global cognitive function in domains of episodic, semantic, and working memory; visuospatial ability; and perceptual speed. Tests scores were standardized and averaged to come up with the composite measure.

Adherence to the DASH diet was scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 10 being a perfect score. The study participants had a mean DASH score of 4.1 (range, 1.5-8.5).

The investigators created linear mixed models incorporating global cognition, individual cognitive domains, DASH total scores, and scores for 10 dietary components. They also created a basic model adjusted for age, sex, education, and total caloric intake, with further adjustment for apolipoprotein E (apo E) status and depression.

Median DASH scores ranged from 2.5 in the lowest tertile to 4.0 in the middle to 5.5 in the highest tertile. At baseline, the mean global cognitive score was 0.14 (range, –3.24 to 1.61).

Over an average of 4.7 years of follow-up, DASH scores were significantly associated in a linear fashion (the higher the score, the slower the rate of decline) in the basic model alone and after adjustment for apo E status (P = .005) and after adjustment for both apo E and depression (P = .006).

The association was significant for all cognitive domains except visuospatial abilities, which trended toward significance but did not reach it (P = .06).

Dietary components significantly associated with slower decline include vegetables (P = .02); nuts, seeds, and legumes (P = .01); total fat (P = .05); and saturated fat (P = .01).

The Rush MAP is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Elsie Heller Brain Bank Endowment Fund, and a Rush University endowment. Dr. Morris reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Eating well may be the best revenge against cognitive decline, a study has shown.

Among 818 dementia-free participants in a longitudinal study of memory and aging, those who adhered to the basic components of the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet had a slower rate of cognitive decline than others who followed more typical American diets, reported Martha Clare Morris, Sc.D., professor and director of the section of nutrition and nutritional epidemiology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

The relationship between diet and cognition was linear, with people who most closely followed the DASH dietary pattern having the slowest rates of decline, Dr. Morris said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

"The individual dietary components that were contributing to this slower decline were higher servings of vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes, and lower intake of total and saturated fats," she said.

The investigators chose to look at dietary patterns because they provide an index of overall dietary quality and incorporate the interactions or synergies that may occur among food groups that constitute a specific pattern.

The DASH diet has been shown to lower blood pressure, increase insulin sensitivity, and reduce weight, serum cholesterol level, inflammation, and oxidative stress.

The diet is similar to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern: heavy on fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, lean meats, fish, poultry, and low- or nonfat dairy, and light on sugar and salt.

To see whether a DASH diet pattern could have similarly beneficial effects on cognition and memory, the authors studied 818 adults who participated in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) and who agreed to fill out a 139-item food frequency questionnaire.

MAP enrolled residents from 40 retirement communities who were dementia free at enrollment and who agreed to have annual cognitive and motor tests and blood draws. Participants also agreed to donate their brains, spinal cords, muscles, and nerve tissue at death.

Participants were tested at baseline and annually with a summary measure of 19 tests assessing global cognitive function in domains of episodic, semantic, and working memory; visuospatial ability; and perceptual speed. Tests scores were standardized and averaged to come up with the composite measure.

Adherence to the DASH diet was scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 10 being a perfect score. The study participants had a mean DASH score of 4.1 (range, 1.5-8.5).

The investigators created linear mixed models incorporating global cognition, individual cognitive domains, DASH total scores, and scores for 10 dietary components. They also created a basic model adjusted for age, sex, education, and total caloric intake, with further adjustment for apolipoprotein E (apo E) status and depression.

Median DASH scores ranged from 2.5 in the lowest tertile to 4.0 in the middle to 5.5 in the highest tertile. At baseline, the mean global cognitive score was 0.14 (range, –3.24 to 1.61).

Over an average of 4.7 years of follow-up, DASH scores were significantly associated in a linear fashion (the higher the score, the slower the rate of decline) in the basic model alone and after adjustment for apo E status (P = .005) and after adjustment for both apo E and depression (P = .006).

The association was significant for all cognitive domains except visuospatial abilities, which trended toward significance but did not reach it (P = .06).

Dietary components significantly associated with slower decline include vegetables (P = .02); nuts, seeds, and legumes (P = .01); total fat (P = .05); and saturated fat (P = .01).

The Rush MAP is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Elsie Heller Brain Bank Endowment Fund, and a Rush University endowment. Dr. Morris reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Eating well may be the best revenge against cognitive decline, a study has shown.

Among 818 dementia-free participants in a longitudinal study of memory and aging, those who adhered to the basic components of the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet had a slower rate of cognitive decline than others who followed more typical American diets, reported Martha Clare Morris, Sc.D., professor and director of the section of nutrition and nutritional epidemiology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

The relationship between diet and cognition was linear, with people who most closely followed the DASH dietary pattern having the slowest rates of decline, Dr. Morris said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

"The individual dietary components that were contributing to this slower decline were higher servings of vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes, and lower intake of total and saturated fats," she said.

The investigators chose to look at dietary patterns because they provide an index of overall dietary quality and incorporate the interactions or synergies that may occur among food groups that constitute a specific pattern.

The DASH diet has been shown to lower blood pressure, increase insulin sensitivity, and reduce weight, serum cholesterol level, inflammation, and oxidative stress.

The diet is similar to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern: heavy on fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, lean meats, fish, poultry, and low- or nonfat dairy, and light on sugar and salt.

To see whether a DASH diet pattern could have similarly beneficial effects on cognition and memory, the authors studied 818 adults who participated in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) and who agreed to fill out a 139-item food frequency questionnaire.

MAP enrolled residents from 40 retirement communities who were dementia free at enrollment and who agreed to have annual cognitive and motor tests and blood draws. Participants also agreed to donate their brains, spinal cords, muscles, and nerve tissue at death.

Participants were tested at baseline and annually with a summary measure of 19 tests assessing global cognitive function in domains of episodic, semantic, and working memory; visuospatial ability; and perceptual speed. Tests scores were standardized and averaged to come up with the composite measure.

Adherence to the DASH diet was scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 10 being a perfect score. The study participants had a mean DASH score of 4.1 (range, 1.5-8.5).

The investigators created linear mixed models incorporating global cognition, individual cognitive domains, DASH total scores, and scores for 10 dietary components. They also created a basic model adjusted for age, sex, education, and total caloric intake, with further adjustment for apolipoprotein E (apo E) status and depression.

Median DASH scores ranged from 2.5 in the lowest tertile to 4.0 in the middle to 5.5 in the highest tertile. At baseline, the mean global cognitive score was 0.14 (range, –3.24 to 1.61).

Over an average of 4.7 years of follow-up, DASH scores were significantly associated in a linear fashion (the higher the score, the slower the rate of decline) in the basic model alone and after adjustment for apo E status (P = .005) and after adjustment for both apo E and depression (P = .006).

The association was significant for all cognitive domains except visuospatial abilities, which trended toward significance but did not reach it (P = .06).

Dietary components significantly associated with slower decline include vegetables (P = .02); nuts, seeds, and legumes (P = .01); total fat (P = .05); and saturated fat (P = .01).

The Rush MAP is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Elsie Heller Brain Bank Endowment Fund, and a Rush University endowment. Dr. Morris reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AAIC 2013

Major finding: Closer adherence to the components of the DASH diet was significantly associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline.

Data source: A prospective, longitudinal study of 818 participants in the Rush Memory and Aging Project.

Disclosures: The Rush MAP is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Elsie Heller Brain Bank Endowment Fund, and a Rush University endowment. Dr. Morris reported having no relevant financial disclosures.