User login

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

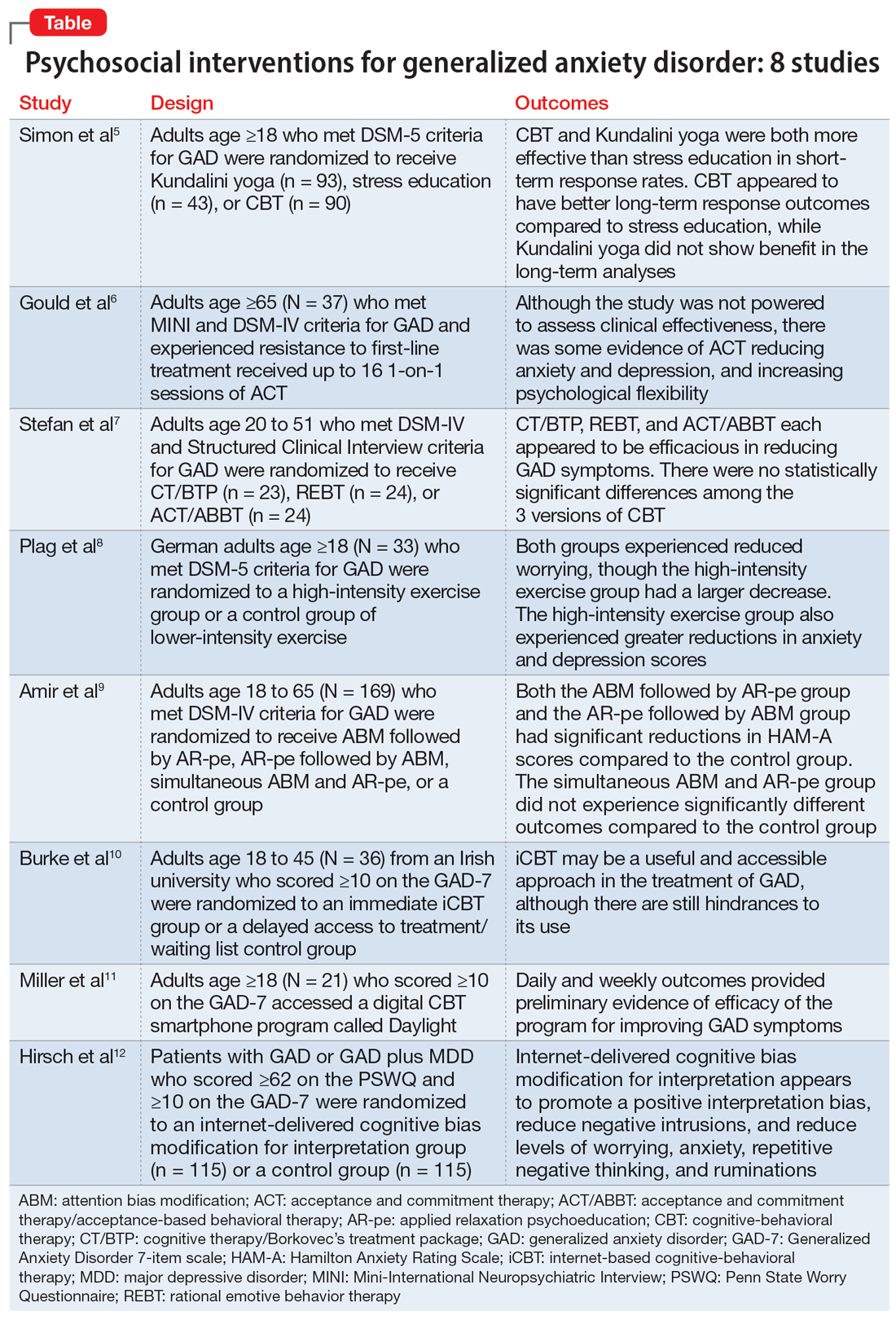

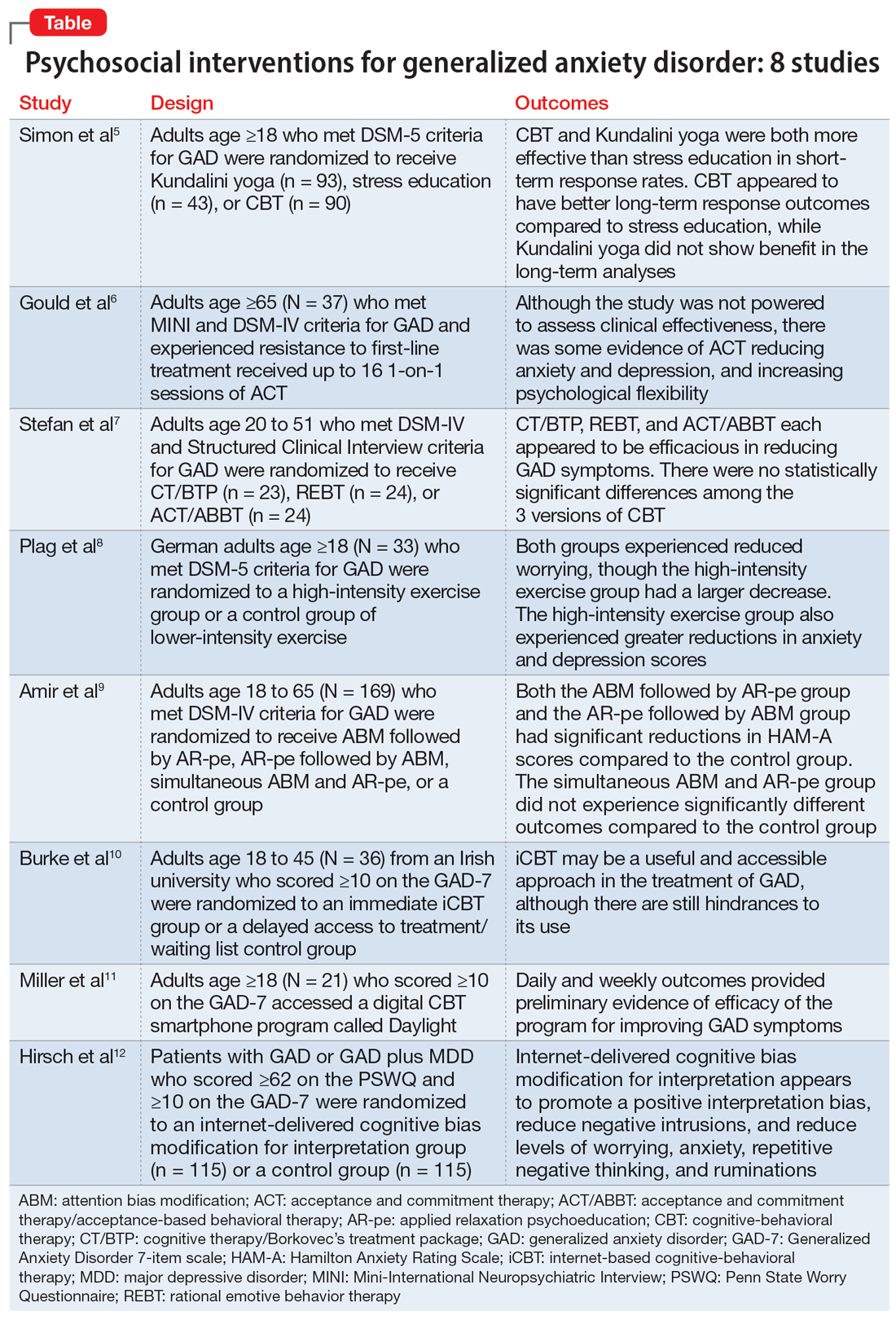

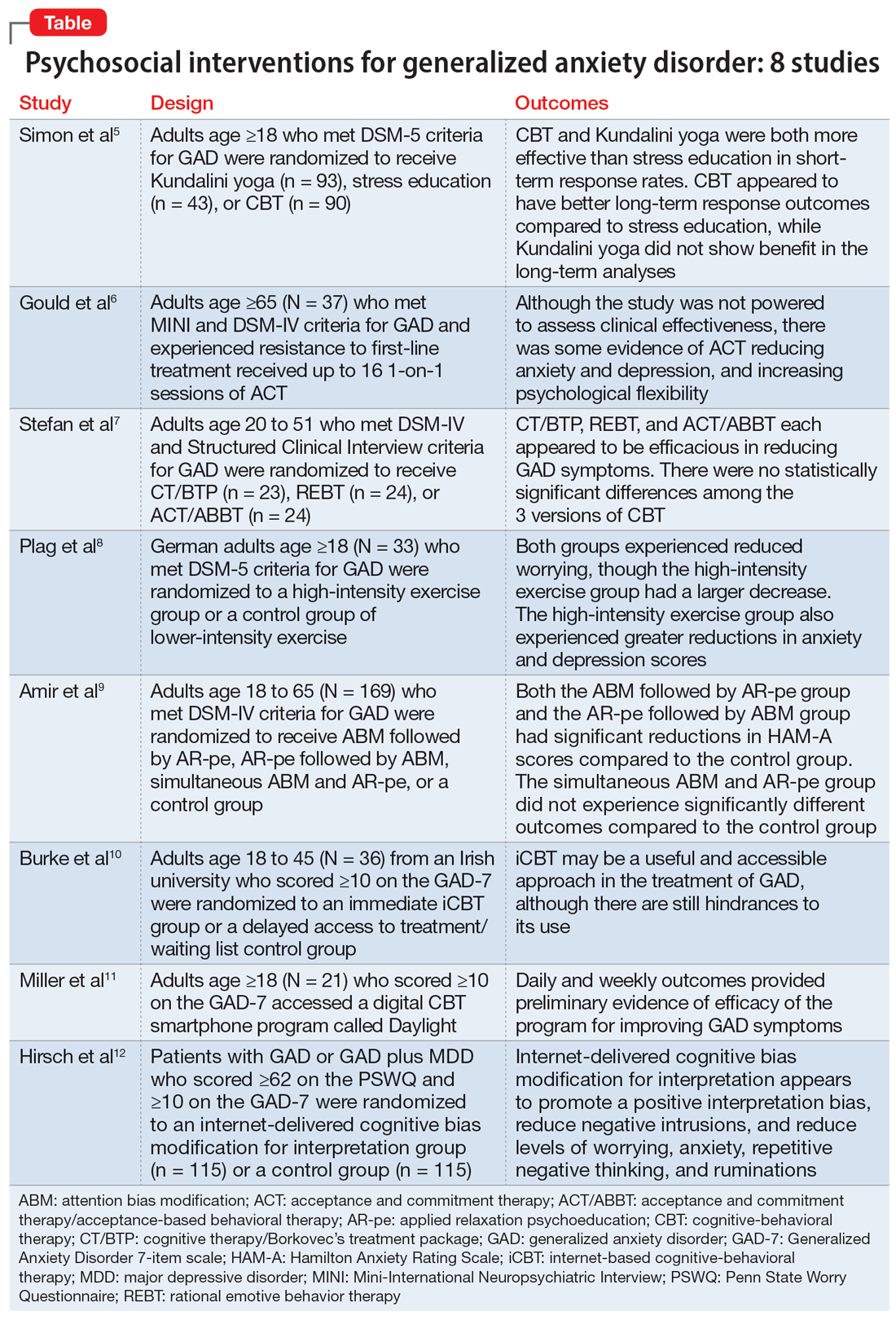

For patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), the intensity, duration, and frequency of an individual’s anxiety and worry are out of proportion to the actual likelihood or impact of an anticipated event, and they often find it difficult to prevent worrisome thoughts from interfering with daily life.1 Successful treatment for GAD is patient-specific and requires clinicians to consider all available psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic options.

In a 2020 meta-analysis of 79 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 11,002 participants diagnosed with GAD, Carl et al2 focused on pooled effect sizes of evidence-based psychotherapies and medications for GAD. Their analysis showed a medium to large effect size (Hedges g = 0.76) for psychotherapy, compared to a small effect size (Hedges g = 0.38) for medication on GAD outcomes. Other meta-analyses have shown that evidence-based psychotherapies have large effect sizes on GAD outcomes.3

However, in most of the studies included in these meta-analyses, the 2 treatment modalities—psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy—use different control types. The pharmacotherapy trials used a placebo, while psychotherapy studies often had a waitlist control. Thus, the findings of these meta-analyses should not lead to the conclusion that psychotherapy is necessarily more effective for GAD symptoms than pharmacotherapy. However, there is clear evidence that psychosocial interventions are at least as effective as medications for treating GAD. Also, patients often prefer psychosocial treatment over medication.

Part 1 (

1. Simon NM, Hofmann SG, Rosenfield D, et al. Efficacy of yoga vs cognitive behavioral therapy vs stress education for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(1):13-20. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2496

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a first-line therapy for GAD.13 However, patients may not pursue CBT due to fiscal and logistical constraints, as well as the stigma associated with it. Yoga is a common complementary health practice used by adults in the United States,14 although evidence has been inconclusive for its use in treating anxiety. Simon et al5 examined the efficacy of Kundalini yoga (KY) vs stress education (SE) and CBT for treating GAD.

Study design

- A prospective, parallel-group, randomized-controlled, single-blind trial in 2 academic centers evaluated 226 adults age ≥18 who met DSM-5 criteria for GAD.

- Participants were randomized into 3 groups: KY (n = 93), SE (n = 43), or CBT (n = 90), and monitored for 12 weeks to determine the efficacy of each therapy.

- Exclusion criteria included current posttraumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, substance use disorders, significant suicidal ideation, mental disorder due to a medical or neurocognitive condition, lifetime psychosis, bipolar disorder (BD), developmental disorders, and having completed more than 5 yoga or CBT sessions in the past 5 years. Additionally, patients were either not taking medication for ≥2 weeks prior to the trial or had a stable regimen for ≥6 weeks.

- Each therapy was guided by 2 instructors during 12 120-minute sessions with 20 minutes of daily assignments and presented in cohorts of 4 to 6 participants.

- The primary outcome was an improvement in score on the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement scale from baseline at Week 12. Secondary measures included scores on the Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire.

Outcomes

- A total of 155 participants finished the posttreatment assessment, with similar completion rates between the groups, and 123 participants completed the 6-month follow-up assessment.

- The KY group had a significantly higher response rate (54.2%) than the SE group (33%) at posttreatment, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 4.59. At 6-month follow-up, the response rate in the KY group was not significantly higher than that of the SE group.

- The CBT group had a significantly higher response rate (70.8%) than the SE group (33%) at posttreatment, with a NNT of 2.62. At 6-month follow-up, the CBT response rate (76.7%) was significantly higher than the SE group (48%), with a NNT of 3.51.

- KY was not found to be as effective as CBT on noninferiority testing.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- CBT and KY were both more effective than SE as assessed by short-term response rates.

- The authors did not find KY to be as effective as CBT at posttreatment or the 6-month follow-up. Additionally, CBT appeared to have better long-term response outcomes compared to SE, while KY did not display a benefit in follow-up analyses. Overall, KY appears to have a less robust efficacy compared to CBT in the treatment of GAD.

- These findings may not generalize to how CBT and yoga are approached in the community. Future studies can assess community-based methods.

2. Gould RL, Wetherell JL, Serfaty MA, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for older people with treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder: the FACTOID feasibility study. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(54):1-150. doi:10.3310/hta25540

Older adults with GAD may experience treatment resistance to first-line therapies, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and CBT. Gould et al6 assessed whether acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) could be a cost-effective option for older adults with treatment-resistant GAD (TR-GAD).

Study design

- In Stage 1 (intervention planning), individual interviews were conducted with 15 participants (11 female) with TR-GAD and 31 health care professionals, as well as 5 academic clinicians. The objective was to assess intervention preferences and priorities.

- Stage 2 included 37 participants, 8 clinicians, and 15 therapists, with the goal of assessing intervention design and feedback on the interventions.

- Participants were age ≥65 and met Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) and DSM-IV criteria for GAD. They were living in the community and had not responded to the 3 steps of the stepped-care approach for GAD (ie, 6 weeks of an age-appropriate dose of antidepressant or a course of individual psychotherapy). Patients with dementia were excluded.

- Patients received ≤16 1-on-1 sessions of ACT.

- Self-reported outcomes were assessed at baseline and Week 20.

- The primary outcomes for Stage 2 were acceptability (attendance and satisfaction with ACT) and feasibility (recruitment and retention).

Outcomes

- ACT had high feasibility, with a recruitment rate of 93% and a retention rate of 81%.

- It also had high acceptability, with 70% of participants attending ≥10 sessions and 60% of participants showing satisfaction with therapy by scoring ≥21 points on the Satisfaction with Therapy subscale of the Satisfaction with Therapy and Therapist Scale-Revised. However, 80% of participants had not finished their ACT sessions when scores were collected.

- At Week 20, 13 patients showed reliable improvement on the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory, and 15 showed no reliable change. Seven participants showed reliable improvement in Geriatric Depression Scale-15 scores and 22 showed no reliable change. Seven participants showed improvement in the Action and Acceptance Questionnaire-II and 19 showed no reliable change.

Conclusions/limitations

- ACT had high levels of feasibility and acceptability, and large RCTs warrant further assessment of the benefits of this intervention.

- There was some evidence of reductions in anxiety and depression, as well as improvement with psychological flexibility.

- The study was not powered to assess clinical effectiveness, and recruitment for Stage 2 was limited to London.

Continue to: #3

3. Stefan S, Cristea IA, Szentagotai Tatar A, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for generalized anxiety disorder: contrasting various CBT approaches in a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(7):1188-1202. doi:10.1002/jclp.22779

Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT for treating GAD.15,16 However, CBT involves varying approaches, which make it difficult to conclude which model of CBT is more effective. Stefan et al7 aimed to assess the efficacy of 3 versions of CBT for GAD.

Study design

- This RCT investigated 3 versions of CBT: cognitive therapy/Borkovec’s treatment package (CT/BTP), rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), and acceptance and commitment therapy/acceptance-based behavioral therapy (ACT/ABBT).

- A total of 75 adults (60 women) age 20 to 51 and diagnosed with GAD by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV were initially randomized to one of the treatment arms for 20 sessions; 4 dropped out before receiving the allocated intervention. Exclusion criteria included panic disorder, severe major depressive disorder (MDD), BD, substance use or dependence, psychotic disorders, suicidal or homicidal ideation, organic brain syndrome, disabling medical conditions, intellectual disability, treatment with a psychotropic drug within the past 3 months, and psychotherapy provided outside the trial.

- The primary outcomes were scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire IV (GAD-Q-IV) and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ). A secondary outcome included assessing negative automatic thoughts by the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire.

Outcomes

- There were no significant differences among the 3 treatment groups with regards to demographic data.

- Approximately 70% of patients (16 of 23) in the CT/BTP group had scores below the cutoff point for response (9) on the GAD-Q-IV, approximately 71% of patients (17 of 24) in the REBT group scored below the cutoff point, and approximately 79% of patients (19 of 24) in the ACT/ABBT group scored below the cutoff point.

- Approximately 83% of patients in the CT/BTP scored below the cutoff point for response (65) on the PSWQ, approximately 83% of patients in the REBT group scored below the cutoff point, and approximately 80% of patients in the ACT/ABBT group scored below the cutoff point.

- There were positive correlations between pre-post changes in GAD symptoms and dysfunctional automatic thoughts in each group.

- There was no statistically significant difference among the 3 versions of CBT.

Conclusions/limitations

- CT/BTP, REBT, and ACT/ABBT each appear to be efficacious in reducing GAD symptoms, allowing the choice of treatment to be determined by patient and clinician preference.

- The study’s small sample size may have prevented differences between the groups from being detected.

- There was no control group, and only 39 of 75 individuals completed the study in its entirety.

4. Plag J, Schmidt-Hellinger P, Klippstein T, et al. Working out the worries: a randomized controlled trial of high intensity interval training in generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;76:102311. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.10231

Research has shown the efficacy of aerobic exercise for various anxiety disorders,17-19 but differs regarding the type of exercise and its intensity, frequency, and duration. There is evidence that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) may be beneficial in treating serious mental illness.20 Plag et al8 examined the efficacy and acceptance of HIIT in patients with GAD.

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- A total of 33 German adults (24 women) age ≥18 who met DSM-5 criteria for GAD were enrolled in a parallel-group, assessor-blinded RCT. Participants were blinded to the hypotheses of the trial, but not to the intervention.

- Participants were randomized to a HIIT group (engaged in HIIT on a bicycle ergometer every second day within 12 days, with each session lasting 20 minutes and consisting of alternating sessions of 77% to 95% maximum heart rate and <70% maximum heart rate) or a control group of lower-intensity exercise (LIT; consisted of 6 30-minute sessions within 12 days involving stretching and adapted yoga positions with heart rate <70% maximum heart rate).

- Exclusion criteria included severe depression, schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder (BPD), substance use disorder, suicidality, epilepsy, severe respiratory or cardiovascular diseases, and current psychotherapy. The use of medications was allowed if the patient was stable ≥4 weeks prior to the trial and remained stable during the trial.

- The primary outcome of worrying was assessed by the PSWQ. Other assessment tools included the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Anxiety Control Questionnaire, and Screening for Somatoform Symptoms-7 (SOMS-7).

Outcomes

- Baseline PSWQ scores in both groups were >60, indicating “high worriers.”

- Both groups experienced reductions in worrying as measured by PSWQ scores. However, the HIIT group had a larger decrease in worrying compared to the LIT group (P < .02). Post-hoc analyses showed significant reductions in symptom severity from baseline to poststudy (P < .01; d = 0.68), and at 30-day follow-up (P < .01; d = 0.62) in the HIIT group. There was no significant difference in the LIT group from baseline to poststudy or at follow-up.

- Secondary outcome measures included a greater reduction in anxiety and depression as determined by change in HAM-A and HAM-D scores in the HIIT group compared to the LIT group.

- All measures showed improvement in the HIIT group, whereas the LIT group showed improvement in HAM-A and HAM-D scores poststudy and at follow-up, as well as SOMS-7 scores at follow-up.

Conclusions/limitations

- HIIT demonstrated a large treatment effect for treating GAD, including somatic symptoms and worrying.

- HIIT displayed a fast onset of action and low cancellation rate, which suggests it is tolerable.

- This study had a small sample size consisting of participants from only 1 institution, which limits generalizability, and did not look at the long-term effects of the interventions.

5. Amir N, Taboas W, Montero M. Feasibility and dissemination of a computerized home-based treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Behav Res Ther. 2019;120:103446. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2019.103446

Many patients with anxiety disorders do not receive treatment, and logistical factors such as limited time, expertise, and available resources hinder patients from obtaining quality CBT. Attention bias modification (ABM) is a computer-based approach in which patients complete tasks guiding their attention away from threat-relevant cues.21 Applied relaxation psychoeducation (AR-pe) is another empirically supported treatment that can be administered via computer. Amir et al9 examined the feasibility and effectiveness of a home-based computerized regimen of sequenced or simultaneous ABM and AR-pe in patients with GAD.

Study design

- A total of 169 adults age 18 to 65 who met DSM-IV criteria for GAD were randomized into 4 groups: ABM followed by AR-pe, AR-pe followed by ABM, simultaneous ABM and AR-pe, or a clinical monitoring assessment only control group (CM).

- Participants were expected to complete up to 24 30-minute sessions on their home computer over 12 weeks.

- Exclusion criteria included current psychotropic medications/CBT initiated 3 months prior to the study, BD, schizophrenia, or substance use disorder.

- The primary outcome measure was anxiety symptoms as assessed by the HAM-A (remission was defined as a score ≤7 at Week 13). Other measures included the PSWQ, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Sheehan Disability Scale, and Beck Depression Inventory.

- Participants were assessed at Month 3, Month 6, and Month 12 poststudy.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Baseline characteristics did not significantly differ between groups.

- In the active groups, 41% of participants met remission criteria, compared to 19% in the CM group.

- The ABM followed by AR-pe group and the AR-pe followed by ABM group had significant reductions in HAM-A scores (P = .003 and P = .020) compared to the CM group.

- The simultaneous ABM and AR-pe group did not have a significant difference in outcomes compared to the CM group (P = .081).

- On the PSWQ, the CM group had a larger decrease in worry than all active cohorts combined, with follow-up analysis indicating the CM group surpassed the ABM group (P = .019).

Conclusions/limitations

- Sequential delivery of ABM and AR-pe may be a viable, easy-to-access treatment option for patients with GAD who have limited access to other therapies.

- Individuals assigned to receive simultaneous ABM and AR-pe appeared to complete fewer tasks compared to those in the sequential groups, which suggests that participants were less inclined to complete all tasks despite being allowed more time.

- This study did not examine the effects of ABM only or AR-pe only.

- This study was unable to accurately assess home usage of the program.

6. Burke J, Richards D, Timulak L. Helpful and hindering events in internet-delivered cognitive behavioural treatment for generalized anxiety. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2019;47(3):386-399. doi:10.1017/S1352465818000504

Patients with GAD may not be able to obtain adequate treatment due to financial or logistical constraints. Internet-delivered interventions are easily accessible and provide an opportunity for patients who cannot or do not want to seek traditional therapy options. Burke et al10 aimed to better understand the useful and impeding events of internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (iCBT).

Study design

- A total of 36 adults (25 women) age 18 to 45 from an Irish university were randomized to an immediate iCBT treatment group or a delayed access to treatment/waiting list control group. The iCBT program, called Calming Anxiety, involved 6 modules of CBT for GAD.

- Participants initially scored ≥10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7).

- The study employed the Helpful and Hindering Aspects of Therapy (HAT) questionnaire to assess the most useful and impeding events in therapy.

- The data were divided into 4 domains: helpful events, helpful impacts, hindering events, and hindering impacts.

Outcomes

- Of the 8 helpful events identified, the top 3 were psychoeducation, supporter interaction, and monitoring.

- Of the 5 helpful impacts identified, the top 3 were support and validation, applying coping strategies/behavioral change, and clarification, awareness, and insight.

- The 2 identified hindering events were treatment content/form and amount of work/technical issues.

- The 3 identified hindering impacts were frustration/irritation, increased anxiety, and isolation.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- iCBT may be a useful and accessible approach for treating GAD, although there are still hindrances to its use.

- This study was qualitative and did not comment on the efficacy of the applied intervention.

- The benefits of iCBT may differ depending on the patient’s level of computer literacy.

7. Miller CB, Gu J, Henry AL, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a digital CBT intervention for symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized multiple-baseline study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2021;70:101609. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2020.101609

Access to CBT is limited due to cost, dearth of trained therapists, scheduling availability, stigma, and transportation. Digital CBT may help overcome these obstacles. Miller et al11 studied the feasibility and efficacy of a new automated, digital CBT intervention named Daylight.

Study design

- This randomized, multiple-baseline, single-case, experimental trial included 21 adults (20 women) age ≥18 who scored ≥10 on the GAD-7 and screened positive for GAD on MINI version 7 for DSM-5.

- Participants were not taking psychotropic medications or had been on a stable medication regimen for ≥4 weeks.

- Exclusion criteria included past or present psychosis, schizophrenia, BD, seizure disorder, substance use disorder, trauma to the head or brain damage, severe cognitive impairment, serious physical health concerns necessitating surgery or with prognosis <6 months, and pregnancy.

- Participants were randomized to 1 of 3 baseline durations: 2 weeks, 4 weeks, or 6 weeks. They then could access the smartphone program Daylight. The trial lasted for 12 to 16 weeks.

- Primary anxiety outcomes were assessed daily and weekly, while secondary outcomes (depressive symptoms, sleep) were measured weekly.

- Postintervention was defined as 6 weeks after the start of the intervention and follow-up was 10 weeks after the start of the intervention.

- Participants were deemed not to have clinically significant anxiety if they scored <10 on GAD-7; not to have significant depressive symptoms if they scored <10 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9); and not to have sleep difficulty if they scored >16 on the Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI-8). The change was considered reliable if patients scored below the previously discussed thresholds and showed a difference in score greater than the known unreliability of the questionnaire (GAD-7 reductions ≥5, PHQ-9 reductions ≥6, SCI-8 increases ≥7).

Outcomes

- In terms of feasibility, 76% of participants completed all 4 modules, 81% completed 3 modules, 86% completed 2 modules, and all participants completed at least 1 module.

- No serious adverse events were observed, but 43% of participants reported unwanted symptoms such as agitation, fatigue, low mood, or reduced motivation.

- As evaluated by the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire, the program received moderate to high credibility scores. Participants indicated they were mostly satisfied with the program, although some expressed technical difficulties and a lack of specificity to their anxiety symptoms.

- Overall daily anxiety scores significantly decreased from baseline to postintervention (P < .001). Weekly anxiety scores significantly decreased from baseline to postintervention (P = .024), and follow-up (P = .017) as measured by the GAD-7.

- For participants with anxiety, 70% no longer had clinically significant anxiety symptoms postintervention, and 65% had both clinically significant and reliable change at postintervention. Eighty percent had clinically significant and reliable change at follow-up.

- For participants with depressive symptoms, 61% had clinical and reliable change at postintervention and 44% maintained both at follow-up.

- For participants with sleep disturbances, 35% had clinical and reliable improvement at postintervention and 40% had clinical and reliable change at follow-up.

Conclusions/limitations

- Daylight appears to be a feasible program with regards to acceptability, engagement, credibility, satisfaction, and safety.

- The daily and weekly outcomes support preliminary evidence of program efficacy in improving GAD symptoms.

- Most participants identified as female and were recruited online, which limits generalizability, and the study had a small sample size.

Continue to: #8

8. Hirsch CR, Krahé C, Whyte J, et al. Internet-delivered interpretation training reduces worry and anxiety in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled experiment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2021;89(7):575-589. doi:10.1037/ccp0000660

The cognitive model of pathological worry posits that worry in GAD occurs due to various factors, including automatic cognitive bias in which ambiguous events are perceived as threatening to the individual.22 Cognitive bias modification for interpretation (CBM) is an approach that assesses an individual’s interpretation bias and resolves ambiguity through the individual’s reading or listening to multiple ambiguous situations.12 Hirsch et al12 examined if an internet-delivered CBM approach would promote positive interpretations and reduce worry and anxiety in patients with GAD.

Study design

- In this dual-arm, parallel group, single-blind RCT, adult participants were randomized to a CBM group (n = 115) or a control group (n = 115); only 186 participants were included in the analyses.

- Patients with GAD only and those with GAD comorbid with MDD who scored ≥62 on the PSWQ and ≥10 on the GAD-7 were recruited. Patients receiving psychotropic medication had to be stable on their regimen for ≥3 months prior to the trial.

- Exclusion criteria included residing outside the United Kingdom, severe depression as measured by a PHQ-9 score ≥23, self-harm in the past 12 months or suicide attempt in past 2 years, a PHQ-9 suicidal ideation score >1, concurrent psychosis, BD, BPD, substance abuse, and current or recent (within the past 6 months) psychological treatment.

- The groups completed up to 10 online training (CBM) or control (listened to ambiguous scenarios but not asked to resolve the ambiguity) sessions in 1 month.

- Primary outcome measures included the scrambled sentences test (SST) and a recognition test (RT) to assess interpretation bias.

- Secondary outcome measures included a breathing focus task (BFT), PSWQ and PSWQ-past week, Ruminative Response Scale (RRS), Repetitive Thinking Questionnaire-trait (RTQ-T), PHQ-9, and GAD-7.

- Scores were assessed preintervention (T0), postintervention (T1), 1 month postintervention (T2), and 3 months postintervention (T3).

Outcomes

- CBM was associated with a more positive interpretation at T1 than the control sessions (P < .001 on both SST and RT).

- CBM was associated with significantly reduced negative intrusions as per BFTs at T1.

- The CBM group had significant less worry as per PSWQ, and significantly less anxiety as per GAD-7 at T1, T2, and T3.

- The CBM group had significantly fewer depressive symptoms as per PHQ-9 at T1, T2, and T3.

- The CBM group had significantly lower levels of ruminations as per RRS at T1, T2, and T3.

- The CBM group had significantly lower levels of general repetitive negative thinking (RNT) as per RTQ-T at T1 and T2, but not T3.

Conclusions/limitations

- Digital CBM appears to promote a positive interpretation bias.

- CBM appears to reduce negative intrusions after the intervention, as well as reduced levels of worrying, anxiety, RNT, and ruminations, with effects lasting ≤3 months except for the RNT.

- CBM appears to be an efficacious, low-intensity, easily accessible intervention that can help individuals with GAD.

- The study recruited participants via advertisements rather than clinical services, and excluded individuals with severe depression.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed., text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

2. Carl E, Witcraft SM, Kauffman BY, et al. Psychological and pharmacological treatments for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD): a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cogn Behav Ther. 2020;49(1):1-21. doi:10.1080/16506073.2018.1560358

3. Cuijpers P, Cristea IA, Karyotaki E, et al. How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta‐analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(3):245-258. doi:10.1002/wps.20346

4. Saeed SA, Majarwitz DJ. Generalized anxiety disorder: 8 studies of biological interventions. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(7):10-12,20,22-27. doi:10.12788/cp.02645

5. Simon NM, Hofmann SG, Rosenfield D, et al. Efficacy of yoga vs cognitive behavioral therapy vs stress education for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(1):13-20. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2496

6. Gould RL, Wetherell JL, Serfaty MA, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for older people with treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder: the FACTOID feasibility study. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(54):1-150. doi:10.3310/hta25540

7. Stefan S, Cristea IA, Szentagotai Tatar A, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for generalized anxiety disorder: contrasting various CBT approaches in a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(7):1188-1202. doi:10.1002/jclp.22779

8. Plag J, Schmidt-Hellinger P, Klippstein T, et al. Working out the worries: a randomized controlled trial of high intensity interval training in generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;76:102311. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102311

9. Amir N, Taboas W, Montero M. Feasibility and dissemination of a computerized home-based treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Behav Res Ther. 2019;120:103446. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2019.103446

10. Burke J, Richards D, Timulak L. Helpful and hindering events in internet-delivered cognitive behavioural treatment for generalized anxiety. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2019;47(3):386-399. doi:10.1017/S1352465818000504

11. Miller CB, Gu J, Henry AL, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a digital CBT intervention for symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized multiple-baseline study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2021;70:101609. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2020.101609

12. Hirsch CR, Krahé C, Whyte J, et al. Internet-delivered interpretation training reduces worry and anxiety in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled experiment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2021;89(7):575-589. doi:10.1037/ccp0000660

13. Hofmann SG, Smits JAJ. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):621-632. doi:10.4088/jcp.v69n0415

14. Clarke TC, Barnes PM, Black LI, et al. Use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractors among U.S. adults aged 18 and over. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;(325):1-8.

15. Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(6):502-514. doi:10.1002/da.22728

16. Covin R, Ouimet AJ, Seeds PM, et al. A meta-analysis of CBT for pathological worry among clients with GAD. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(1):108-116. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.002

17. Merom D, Phongsavan P, Wagner R, et al. Promoting walking as an adjunct intervention to group cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders--a pilot group randomized trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(6):959-968. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.010

18. Herring MP, Jacob ML, Suveg C, et al. Feasibility of exercise training for the short-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81(1):21-28. doi:10.1159/000327898

19. Bischoff S, Wieder G, Einsle F, et al. Running for extinction? Aerobic exercise as an augmentation of exposure therapy in panic disorder with agoraphobia. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;101:34-41. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.03.001

20. Korman N, Armour M, Chapman J, et al. High Intensity Interval training (HIIT) for people with severe mental illness: a systematic review & meta-analysis of intervention studies- considering diverse approaches for mental and physical recovery. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112601. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112601

21. Amir N, Beard C, Cobb M, et al. Attention modification program in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(1):28-33. doi:10.1037/a0012589

22. Hirsh CR, Mathews A. A cognitive model of pathological worry. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(10):636-646. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.007

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

For patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), the intensity, duration, and frequency of an individual’s anxiety and worry are out of proportion to the actual likelihood or impact of an anticipated event, and they often find it difficult to prevent worrisome thoughts from interfering with daily life.1 Successful treatment for GAD is patient-specific and requires clinicians to consider all available psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic options.

In a 2020 meta-analysis of 79 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 11,002 participants diagnosed with GAD, Carl et al2 focused on pooled effect sizes of evidence-based psychotherapies and medications for GAD. Their analysis showed a medium to large effect size (Hedges g = 0.76) for psychotherapy, compared to a small effect size (Hedges g = 0.38) for medication on GAD outcomes. Other meta-analyses have shown that evidence-based psychotherapies have large effect sizes on GAD outcomes.3

However, in most of the studies included in these meta-analyses, the 2 treatment modalities—psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy—use different control types. The pharmacotherapy trials used a placebo, while psychotherapy studies often had a waitlist control. Thus, the findings of these meta-analyses should not lead to the conclusion that psychotherapy is necessarily more effective for GAD symptoms than pharmacotherapy. However, there is clear evidence that psychosocial interventions are at least as effective as medications for treating GAD. Also, patients often prefer psychosocial treatment over medication.

Part 1 (

1. Simon NM, Hofmann SG, Rosenfield D, et al. Efficacy of yoga vs cognitive behavioral therapy vs stress education for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(1):13-20. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2496

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a first-line therapy for GAD.13 However, patients may not pursue CBT due to fiscal and logistical constraints, as well as the stigma associated with it. Yoga is a common complementary health practice used by adults in the United States,14 although evidence has been inconclusive for its use in treating anxiety. Simon et al5 examined the efficacy of Kundalini yoga (KY) vs stress education (SE) and CBT for treating GAD.

Study design

- A prospective, parallel-group, randomized-controlled, single-blind trial in 2 academic centers evaluated 226 adults age ≥18 who met DSM-5 criteria for GAD.

- Participants were randomized into 3 groups: KY (n = 93), SE (n = 43), or CBT (n = 90), and monitored for 12 weeks to determine the efficacy of each therapy.

- Exclusion criteria included current posttraumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, substance use disorders, significant suicidal ideation, mental disorder due to a medical or neurocognitive condition, lifetime psychosis, bipolar disorder (BD), developmental disorders, and having completed more than 5 yoga or CBT sessions in the past 5 years. Additionally, patients were either not taking medication for ≥2 weeks prior to the trial or had a stable regimen for ≥6 weeks.

- Each therapy was guided by 2 instructors during 12 120-minute sessions with 20 minutes of daily assignments and presented in cohorts of 4 to 6 participants.

- The primary outcome was an improvement in score on the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement scale from baseline at Week 12. Secondary measures included scores on the Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire.

Outcomes

- A total of 155 participants finished the posttreatment assessment, with similar completion rates between the groups, and 123 participants completed the 6-month follow-up assessment.

- The KY group had a significantly higher response rate (54.2%) than the SE group (33%) at posttreatment, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 4.59. At 6-month follow-up, the response rate in the KY group was not significantly higher than that of the SE group.

- The CBT group had a significantly higher response rate (70.8%) than the SE group (33%) at posttreatment, with a NNT of 2.62. At 6-month follow-up, the CBT response rate (76.7%) was significantly higher than the SE group (48%), with a NNT of 3.51.

- KY was not found to be as effective as CBT on noninferiority testing.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- CBT and KY were both more effective than SE as assessed by short-term response rates.

- The authors did not find KY to be as effective as CBT at posttreatment or the 6-month follow-up. Additionally, CBT appeared to have better long-term response outcomes compared to SE, while KY did not display a benefit in follow-up analyses. Overall, KY appears to have a less robust efficacy compared to CBT in the treatment of GAD.

- These findings may not generalize to how CBT and yoga are approached in the community. Future studies can assess community-based methods.

2. Gould RL, Wetherell JL, Serfaty MA, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for older people with treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder: the FACTOID feasibility study. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(54):1-150. doi:10.3310/hta25540

Older adults with GAD may experience treatment resistance to first-line therapies, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and CBT. Gould et al6 assessed whether acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) could be a cost-effective option for older adults with treatment-resistant GAD (TR-GAD).

Study design

- In Stage 1 (intervention planning), individual interviews were conducted with 15 participants (11 female) with TR-GAD and 31 health care professionals, as well as 5 academic clinicians. The objective was to assess intervention preferences and priorities.

- Stage 2 included 37 participants, 8 clinicians, and 15 therapists, with the goal of assessing intervention design and feedback on the interventions.

- Participants were age ≥65 and met Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) and DSM-IV criteria for GAD. They were living in the community and had not responded to the 3 steps of the stepped-care approach for GAD (ie, 6 weeks of an age-appropriate dose of antidepressant or a course of individual psychotherapy). Patients with dementia were excluded.

- Patients received ≤16 1-on-1 sessions of ACT.

- Self-reported outcomes were assessed at baseline and Week 20.

- The primary outcomes for Stage 2 were acceptability (attendance and satisfaction with ACT) and feasibility (recruitment and retention).

Outcomes

- ACT had high feasibility, with a recruitment rate of 93% and a retention rate of 81%.

- It also had high acceptability, with 70% of participants attending ≥10 sessions and 60% of participants showing satisfaction with therapy by scoring ≥21 points on the Satisfaction with Therapy subscale of the Satisfaction with Therapy and Therapist Scale-Revised. However, 80% of participants had not finished their ACT sessions when scores were collected.

- At Week 20, 13 patients showed reliable improvement on the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory, and 15 showed no reliable change. Seven participants showed reliable improvement in Geriatric Depression Scale-15 scores and 22 showed no reliable change. Seven participants showed improvement in the Action and Acceptance Questionnaire-II and 19 showed no reliable change.

Conclusions/limitations

- ACT had high levels of feasibility and acceptability, and large RCTs warrant further assessment of the benefits of this intervention.

- There was some evidence of reductions in anxiety and depression, as well as improvement with psychological flexibility.

- The study was not powered to assess clinical effectiveness, and recruitment for Stage 2 was limited to London.

Continue to: #3

3. Stefan S, Cristea IA, Szentagotai Tatar A, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for generalized anxiety disorder: contrasting various CBT approaches in a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(7):1188-1202. doi:10.1002/jclp.22779

Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT for treating GAD.15,16 However, CBT involves varying approaches, which make it difficult to conclude which model of CBT is more effective. Stefan et al7 aimed to assess the efficacy of 3 versions of CBT for GAD.

Study design

- This RCT investigated 3 versions of CBT: cognitive therapy/Borkovec’s treatment package (CT/BTP), rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), and acceptance and commitment therapy/acceptance-based behavioral therapy (ACT/ABBT).

- A total of 75 adults (60 women) age 20 to 51 and diagnosed with GAD by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV were initially randomized to one of the treatment arms for 20 sessions; 4 dropped out before receiving the allocated intervention. Exclusion criteria included panic disorder, severe major depressive disorder (MDD), BD, substance use or dependence, psychotic disorders, suicidal or homicidal ideation, organic brain syndrome, disabling medical conditions, intellectual disability, treatment with a psychotropic drug within the past 3 months, and psychotherapy provided outside the trial.

- The primary outcomes were scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire IV (GAD-Q-IV) and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ). A secondary outcome included assessing negative automatic thoughts by the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire.

Outcomes

- There were no significant differences among the 3 treatment groups with regards to demographic data.

- Approximately 70% of patients (16 of 23) in the CT/BTP group had scores below the cutoff point for response (9) on the GAD-Q-IV, approximately 71% of patients (17 of 24) in the REBT group scored below the cutoff point, and approximately 79% of patients (19 of 24) in the ACT/ABBT group scored below the cutoff point.

- Approximately 83% of patients in the CT/BTP scored below the cutoff point for response (65) on the PSWQ, approximately 83% of patients in the REBT group scored below the cutoff point, and approximately 80% of patients in the ACT/ABBT group scored below the cutoff point.

- There were positive correlations between pre-post changes in GAD symptoms and dysfunctional automatic thoughts in each group.

- There was no statistically significant difference among the 3 versions of CBT.

Conclusions/limitations

- CT/BTP, REBT, and ACT/ABBT each appear to be efficacious in reducing GAD symptoms, allowing the choice of treatment to be determined by patient and clinician preference.

- The study’s small sample size may have prevented differences between the groups from being detected.

- There was no control group, and only 39 of 75 individuals completed the study in its entirety.

4. Plag J, Schmidt-Hellinger P, Klippstein T, et al. Working out the worries: a randomized controlled trial of high intensity interval training in generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;76:102311. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.10231

Research has shown the efficacy of aerobic exercise for various anxiety disorders,17-19 but differs regarding the type of exercise and its intensity, frequency, and duration. There is evidence that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) may be beneficial in treating serious mental illness.20 Plag et al8 examined the efficacy and acceptance of HIIT in patients with GAD.

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- A total of 33 German adults (24 women) age ≥18 who met DSM-5 criteria for GAD were enrolled in a parallel-group, assessor-blinded RCT. Participants were blinded to the hypotheses of the trial, but not to the intervention.

- Participants were randomized to a HIIT group (engaged in HIIT on a bicycle ergometer every second day within 12 days, with each session lasting 20 minutes and consisting of alternating sessions of 77% to 95% maximum heart rate and <70% maximum heart rate) or a control group of lower-intensity exercise (LIT; consisted of 6 30-minute sessions within 12 days involving stretching and adapted yoga positions with heart rate <70% maximum heart rate).

- Exclusion criteria included severe depression, schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder (BPD), substance use disorder, suicidality, epilepsy, severe respiratory or cardiovascular diseases, and current psychotherapy. The use of medications was allowed if the patient was stable ≥4 weeks prior to the trial and remained stable during the trial.

- The primary outcome of worrying was assessed by the PSWQ. Other assessment tools included the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Anxiety Control Questionnaire, and Screening for Somatoform Symptoms-7 (SOMS-7).

Outcomes

- Baseline PSWQ scores in both groups were >60, indicating “high worriers.”

- Both groups experienced reductions in worrying as measured by PSWQ scores. However, the HIIT group had a larger decrease in worrying compared to the LIT group (P < .02). Post-hoc analyses showed significant reductions in symptom severity from baseline to poststudy (P < .01; d = 0.68), and at 30-day follow-up (P < .01; d = 0.62) in the HIIT group. There was no significant difference in the LIT group from baseline to poststudy or at follow-up.

- Secondary outcome measures included a greater reduction in anxiety and depression as determined by change in HAM-A and HAM-D scores in the HIIT group compared to the LIT group.

- All measures showed improvement in the HIIT group, whereas the LIT group showed improvement in HAM-A and HAM-D scores poststudy and at follow-up, as well as SOMS-7 scores at follow-up.

Conclusions/limitations

- HIIT demonstrated a large treatment effect for treating GAD, including somatic symptoms and worrying.

- HIIT displayed a fast onset of action and low cancellation rate, which suggests it is tolerable.

- This study had a small sample size consisting of participants from only 1 institution, which limits generalizability, and did not look at the long-term effects of the interventions.

5. Amir N, Taboas W, Montero M. Feasibility and dissemination of a computerized home-based treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Behav Res Ther. 2019;120:103446. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2019.103446

Many patients with anxiety disorders do not receive treatment, and logistical factors such as limited time, expertise, and available resources hinder patients from obtaining quality CBT. Attention bias modification (ABM) is a computer-based approach in which patients complete tasks guiding their attention away from threat-relevant cues.21 Applied relaxation psychoeducation (AR-pe) is another empirically supported treatment that can be administered via computer. Amir et al9 examined the feasibility and effectiveness of a home-based computerized regimen of sequenced or simultaneous ABM and AR-pe in patients with GAD.

Study design

- A total of 169 adults age 18 to 65 who met DSM-IV criteria for GAD were randomized into 4 groups: ABM followed by AR-pe, AR-pe followed by ABM, simultaneous ABM and AR-pe, or a clinical monitoring assessment only control group (CM).

- Participants were expected to complete up to 24 30-minute sessions on their home computer over 12 weeks.

- Exclusion criteria included current psychotropic medications/CBT initiated 3 months prior to the study, BD, schizophrenia, or substance use disorder.

- The primary outcome measure was anxiety symptoms as assessed by the HAM-A (remission was defined as a score ≤7 at Week 13). Other measures included the PSWQ, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Sheehan Disability Scale, and Beck Depression Inventory.

- Participants were assessed at Month 3, Month 6, and Month 12 poststudy.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Baseline characteristics did not significantly differ between groups.

- In the active groups, 41% of participants met remission criteria, compared to 19% in the CM group.

- The ABM followed by AR-pe group and the AR-pe followed by ABM group had significant reductions in HAM-A scores (P = .003 and P = .020) compared to the CM group.

- The simultaneous ABM and AR-pe group did not have a significant difference in outcomes compared to the CM group (P = .081).

- On the PSWQ, the CM group had a larger decrease in worry than all active cohorts combined, with follow-up analysis indicating the CM group surpassed the ABM group (P = .019).

Conclusions/limitations

- Sequential delivery of ABM and AR-pe may be a viable, easy-to-access treatment option for patients with GAD who have limited access to other therapies.

- Individuals assigned to receive simultaneous ABM and AR-pe appeared to complete fewer tasks compared to those in the sequential groups, which suggests that participants were less inclined to complete all tasks despite being allowed more time.

- This study did not examine the effects of ABM only or AR-pe only.

- This study was unable to accurately assess home usage of the program.

6. Burke J, Richards D, Timulak L. Helpful and hindering events in internet-delivered cognitive behavioural treatment for generalized anxiety. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2019;47(3):386-399. doi:10.1017/S1352465818000504

Patients with GAD may not be able to obtain adequate treatment due to financial or logistical constraints. Internet-delivered interventions are easily accessible and provide an opportunity for patients who cannot or do not want to seek traditional therapy options. Burke et al10 aimed to better understand the useful and impeding events of internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (iCBT).

Study design

- A total of 36 adults (25 women) age 18 to 45 from an Irish university were randomized to an immediate iCBT treatment group or a delayed access to treatment/waiting list control group. The iCBT program, called Calming Anxiety, involved 6 modules of CBT for GAD.

- Participants initially scored ≥10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7).

- The study employed the Helpful and Hindering Aspects of Therapy (HAT) questionnaire to assess the most useful and impeding events in therapy.

- The data were divided into 4 domains: helpful events, helpful impacts, hindering events, and hindering impacts.

Outcomes

- Of the 8 helpful events identified, the top 3 were psychoeducation, supporter interaction, and monitoring.

- Of the 5 helpful impacts identified, the top 3 were support and validation, applying coping strategies/behavioral change, and clarification, awareness, and insight.

- The 2 identified hindering events were treatment content/form and amount of work/technical issues.

- The 3 identified hindering impacts were frustration/irritation, increased anxiety, and isolation.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- iCBT may be a useful and accessible approach for treating GAD, although there are still hindrances to its use.

- This study was qualitative and did not comment on the efficacy of the applied intervention.

- The benefits of iCBT may differ depending on the patient’s level of computer literacy.

7. Miller CB, Gu J, Henry AL, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a digital CBT intervention for symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized multiple-baseline study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2021;70:101609. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2020.101609

Access to CBT is limited due to cost, dearth of trained therapists, scheduling availability, stigma, and transportation. Digital CBT may help overcome these obstacles. Miller et al11 studied the feasibility and efficacy of a new automated, digital CBT intervention named Daylight.

Study design

- This randomized, multiple-baseline, single-case, experimental trial included 21 adults (20 women) age ≥18 who scored ≥10 on the GAD-7 and screened positive for GAD on MINI version 7 for DSM-5.

- Participants were not taking psychotropic medications or had been on a stable medication regimen for ≥4 weeks.

- Exclusion criteria included past or present psychosis, schizophrenia, BD, seizure disorder, substance use disorder, trauma to the head or brain damage, severe cognitive impairment, serious physical health concerns necessitating surgery or with prognosis <6 months, and pregnancy.

- Participants were randomized to 1 of 3 baseline durations: 2 weeks, 4 weeks, or 6 weeks. They then could access the smartphone program Daylight. The trial lasted for 12 to 16 weeks.

- Primary anxiety outcomes were assessed daily and weekly, while secondary outcomes (depressive symptoms, sleep) were measured weekly.

- Postintervention was defined as 6 weeks after the start of the intervention and follow-up was 10 weeks after the start of the intervention.

- Participants were deemed not to have clinically significant anxiety if they scored <10 on GAD-7; not to have significant depressive symptoms if they scored <10 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9); and not to have sleep difficulty if they scored >16 on the Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI-8). The change was considered reliable if patients scored below the previously discussed thresholds and showed a difference in score greater than the known unreliability of the questionnaire (GAD-7 reductions ≥5, PHQ-9 reductions ≥6, SCI-8 increases ≥7).

Outcomes

- In terms of feasibility, 76% of participants completed all 4 modules, 81% completed 3 modules, 86% completed 2 modules, and all participants completed at least 1 module.

- No serious adverse events were observed, but 43% of participants reported unwanted symptoms such as agitation, fatigue, low mood, or reduced motivation.

- As evaluated by the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire, the program received moderate to high credibility scores. Participants indicated they were mostly satisfied with the program, although some expressed technical difficulties and a lack of specificity to their anxiety symptoms.

- Overall daily anxiety scores significantly decreased from baseline to postintervention (P < .001). Weekly anxiety scores significantly decreased from baseline to postintervention (P = .024), and follow-up (P = .017) as measured by the GAD-7.

- For participants with anxiety, 70% no longer had clinically significant anxiety symptoms postintervention, and 65% had both clinically significant and reliable change at postintervention. Eighty percent had clinically significant and reliable change at follow-up.

- For participants with depressive symptoms, 61% had clinical and reliable change at postintervention and 44% maintained both at follow-up.

- For participants with sleep disturbances, 35% had clinical and reliable improvement at postintervention and 40% had clinical and reliable change at follow-up.

Conclusions/limitations

- Daylight appears to be a feasible program with regards to acceptability, engagement, credibility, satisfaction, and safety.

- The daily and weekly outcomes support preliminary evidence of program efficacy in improving GAD symptoms.

- Most participants identified as female and were recruited online, which limits generalizability, and the study had a small sample size.

Continue to: #8

8. Hirsch CR, Krahé C, Whyte J, et al. Internet-delivered interpretation training reduces worry and anxiety in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled experiment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2021;89(7):575-589. doi:10.1037/ccp0000660

The cognitive model of pathological worry posits that worry in GAD occurs due to various factors, including automatic cognitive bias in which ambiguous events are perceived as threatening to the individual.22 Cognitive bias modification for interpretation (CBM) is an approach that assesses an individual’s interpretation bias and resolves ambiguity through the individual’s reading or listening to multiple ambiguous situations.12 Hirsch et al12 examined if an internet-delivered CBM approach would promote positive interpretations and reduce worry and anxiety in patients with GAD.

Study design

- In this dual-arm, parallel group, single-blind RCT, adult participants were randomized to a CBM group (n = 115) or a control group (n = 115); only 186 participants were included in the analyses.

- Patients with GAD only and those with GAD comorbid with MDD who scored ≥62 on the PSWQ and ≥10 on the GAD-7 were recruited. Patients receiving psychotropic medication had to be stable on their regimen for ≥3 months prior to the trial.

- Exclusion criteria included residing outside the United Kingdom, severe depression as measured by a PHQ-9 score ≥23, self-harm in the past 12 months or suicide attempt in past 2 years, a PHQ-9 suicidal ideation score >1, concurrent psychosis, BD, BPD, substance abuse, and current or recent (within the past 6 months) psychological treatment.

- The groups completed up to 10 online training (CBM) or control (listened to ambiguous scenarios but not asked to resolve the ambiguity) sessions in 1 month.

- Primary outcome measures included the scrambled sentences test (SST) and a recognition test (RT) to assess interpretation bias.

- Secondary outcome measures included a breathing focus task (BFT), PSWQ and PSWQ-past week, Ruminative Response Scale (RRS), Repetitive Thinking Questionnaire-trait (RTQ-T), PHQ-9, and GAD-7.

- Scores were assessed preintervention (T0), postintervention (T1), 1 month postintervention (T2), and 3 months postintervention (T3).

Outcomes

- CBM was associated with a more positive interpretation at T1 than the control sessions (P < .001 on both SST and RT).

- CBM was associated with significantly reduced negative intrusions as per BFTs at T1.

- The CBM group had significant less worry as per PSWQ, and significantly less anxiety as per GAD-7 at T1, T2, and T3.

- The CBM group had significantly fewer depressive symptoms as per PHQ-9 at T1, T2, and T3.

- The CBM group had significantly lower levels of ruminations as per RRS at T1, T2, and T3.

- The CBM group had significantly lower levels of general repetitive negative thinking (RNT) as per RTQ-T at T1 and T2, but not T3.

Conclusions/limitations

- Digital CBM appears to promote a positive interpretation bias.

- CBM appears to reduce negative intrusions after the intervention, as well as reduced levels of worrying, anxiety, RNT, and ruminations, with effects lasting ≤3 months except for the RNT.

- CBM appears to be an efficacious, low-intensity, easily accessible intervention that can help individuals with GAD.

- The study recruited participants via advertisements rather than clinical services, and excluded individuals with severe depression.

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

For patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), the intensity, duration, and frequency of an individual’s anxiety and worry are out of proportion to the actual likelihood or impact of an anticipated event, and they often find it difficult to prevent worrisome thoughts from interfering with daily life.1 Successful treatment for GAD is patient-specific and requires clinicians to consider all available psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic options.

In a 2020 meta-analysis of 79 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 11,002 participants diagnosed with GAD, Carl et al2 focused on pooled effect sizes of evidence-based psychotherapies and medications for GAD. Their analysis showed a medium to large effect size (Hedges g = 0.76) for psychotherapy, compared to a small effect size (Hedges g = 0.38) for medication on GAD outcomes. Other meta-analyses have shown that evidence-based psychotherapies have large effect sizes on GAD outcomes.3

However, in most of the studies included in these meta-analyses, the 2 treatment modalities—psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy—use different control types. The pharmacotherapy trials used a placebo, while psychotherapy studies often had a waitlist control. Thus, the findings of these meta-analyses should not lead to the conclusion that psychotherapy is necessarily more effective for GAD symptoms than pharmacotherapy. However, there is clear evidence that psychosocial interventions are at least as effective as medications for treating GAD. Also, patients often prefer psychosocial treatment over medication.

Part 1 (

1. Simon NM, Hofmann SG, Rosenfield D, et al. Efficacy of yoga vs cognitive behavioral therapy vs stress education for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(1):13-20. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2496

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a first-line therapy for GAD.13 However, patients may not pursue CBT due to fiscal and logistical constraints, as well as the stigma associated with it. Yoga is a common complementary health practice used by adults in the United States,14 although evidence has been inconclusive for its use in treating anxiety. Simon et al5 examined the efficacy of Kundalini yoga (KY) vs stress education (SE) and CBT for treating GAD.

Study design

- A prospective, parallel-group, randomized-controlled, single-blind trial in 2 academic centers evaluated 226 adults age ≥18 who met DSM-5 criteria for GAD.

- Participants were randomized into 3 groups: KY (n = 93), SE (n = 43), or CBT (n = 90), and monitored for 12 weeks to determine the efficacy of each therapy.

- Exclusion criteria included current posttraumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, substance use disorders, significant suicidal ideation, mental disorder due to a medical or neurocognitive condition, lifetime psychosis, bipolar disorder (BD), developmental disorders, and having completed more than 5 yoga or CBT sessions in the past 5 years. Additionally, patients were either not taking medication for ≥2 weeks prior to the trial or had a stable regimen for ≥6 weeks.

- Each therapy was guided by 2 instructors during 12 120-minute sessions with 20 minutes of daily assignments and presented in cohorts of 4 to 6 participants.

- The primary outcome was an improvement in score on the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement scale from baseline at Week 12. Secondary measures included scores on the Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire.

Outcomes

- A total of 155 participants finished the posttreatment assessment, with similar completion rates between the groups, and 123 participants completed the 6-month follow-up assessment.

- The KY group had a significantly higher response rate (54.2%) than the SE group (33%) at posttreatment, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 4.59. At 6-month follow-up, the response rate in the KY group was not significantly higher than that of the SE group.

- The CBT group had a significantly higher response rate (70.8%) than the SE group (33%) at posttreatment, with a NNT of 2.62. At 6-month follow-up, the CBT response rate (76.7%) was significantly higher than the SE group (48%), with a NNT of 3.51.

- KY was not found to be as effective as CBT on noninferiority testing.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- CBT and KY were both more effective than SE as assessed by short-term response rates.

- The authors did not find KY to be as effective as CBT at posttreatment or the 6-month follow-up. Additionally, CBT appeared to have better long-term response outcomes compared to SE, while KY did not display a benefit in follow-up analyses. Overall, KY appears to have a less robust efficacy compared to CBT in the treatment of GAD.

- These findings may not generalize to how CBT and yoga are approached in the community. Future studies can assess community-based methods.

2. Gould RL, Wetherell JL, Serfaty MA, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for older people with treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder: the FACTOID feasibility study. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(54):1-150. doi:10.3310/hta25540

Older adults with GAD may experience treatment resistance to first-line therapies, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and CBT. Gould et al6 assessed whether acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) could be a cost-effective option for older adults with treatment-resistant GAD (TR-GAD).

Study design

- In Stage 1 (intervention planning), individual interviews were conducted with 15 participants (11 female) with TR-GAD and 31 health care professionals, as well as 5 academic clinicians. The objective was to assess intervention preferences and priorities.

- Stage 2 included 37 participants, 8 clinicians, and 15 therapists, with the goal of assessing intervention design and feedback on the interventions.

- Participants were age ≥65 and met Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) and DSM-IV criteria for GAD. They were living in the community and had not responded to the 3 steps of the stepped-care approach for GAD (ie, 6 weeks of an age-appropriate dose of antidepressant or a course of individual psychotherapy). Patients with dementia were excluded.

- Patients received ≤16 1-on-1 sessions of ACT.

- Self-reported outcomes were assessed at baseline and Week 20.

- The primary outcomes for Stage 2 were acceptability (attendance and satisfaction with ACT) and feasibility (recruitment and retention).

Outcomes

- ACT had high feasibility, with a recruitment rate of 93% and a retention rate of 81%.

- It also had high acceptability, with 70% of participants attending ≥10 sessions and 60% of participants showing satisfaction with therapy by scoring ≥21 points on the Satisfaction with Therapy subscale of the Satisfaction with Therapy and Therapist Scale-Revised. However, 80% of participants had not finished their ACT sessions when scores were collected.

- At Week 20, 13 patients showed reliable improvement on the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory, and 15 showed no reliable change. Seven participants showed reliable improvement in Geriatric Depression Scale-15 scores and 22 showed no reliable change. Seven participants showed improvement in the Action and Acceptance Questionnaire-II and 19 showed no reliable change.

Conclusions/limitations

- ACT had high levels of feasibility and acceptability, and large RCTs warrant further assessment of the benefits of this intervention.

- There was some evidence of reductions in anxiety and depression, as well as improvement with psychological flexibility.

- The study was not powered to assess clinical effectiveness, and recruitment for Stage 2 was limited to London.

Continue to: #3

3. Stefan S, Cristea IA, Szentagotai Tatar A, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for generalized anxiety disorder: contrasting various CBT approaches in a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(7):1188-1202. doi:10.1002/jclp.22779

Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT for treating GAD.15,16 However, CBT involves varying approaches, which make it difficult to conclude which model of CBT is more effective. Stefan et al7 aimed to assess the efficacy of 3 versions of CBT for GAD.

Study design

- This RCT investigated 3 versions of CBT: cognitive therapy/Borkovec’s treatment package (CT/BTP), rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), and acceptance and commitment therapy/acceptance-based behavioral therapy (ACT/ABBT).

- A total of 75 adults (60 women) age 20 to 51 and diagnosed with GAD by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV were initially randomized to one of the treatment arms for 20 sessions; 4 dropped out before receiving the allocated intervention. Exclusion criteria included panic disorder, severe major depressive disorder (MDD), BD, substance use or dependence, psychotic disorders, suicidal or homicidal ideation, organic brain syndrome, disabling medical conditions, intellectual disability, treatment with a psychotropic drug within the past 3 months, and psychotherapy provided outside the trial.

- The primary outcomes were scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire IV (GAD-Q-IV) and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ). A secondary outcome included assessing negative automatic thoughts by the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire.

Outcomes

- There were no significant differences among the 3 treatment groups with regards to demographic data.

- Approximately 70% of patients (16 of 23) in the CT/BTP group had scores below the cutoff point for response (9) on the GAD-Q-IV, approximately 71% of patients (17 of 24) in the REBT group scored below the cutoff point, and approximately 79% of patients (19 of 24) in the ACT/ABBT group scored below the cutoff point.

- Approximately 83% of patients in the CT/BTP scored below the cutoff point for response (65) on the PSWQ, approximately 83% of patients in the REBT group scored below the cutoff point, and approximately 80% of patients in the ACT/ABBT group scored below the cutoff point.

- There were positive correlations between pre-post changes in GAD symptoms and dysfunctional automatic thoughts in each group.

- There was no statistically significant difference among the 3 versions of CBT.

Conclusions/limitations

- CT/BTP, REBT, and ACT/ABBT each appear to be efficacious in reducing GAD symptoms, allowing the choice of treatment to be determined by patient and clinician preference.

- The study’s small sample size may have prevented differences between the groups from being detected.

- There was no control group, and only 39 of 75 individuals completed the study in its entirety.

4. Plag J, Schmidt-Hellinger P, Klippstein T, et al. Working out the worries: a randomized controlled trial of high intensity interval training in generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;76:102311. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.10231

Research has shown the efficacy of aerobic exercise for various anxiety disorders,17-19 but differs regarding the type of exercise and its intensity, frequency, and duration. There is evidence that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) may be beneficial in treating serious mental illness.20 Plag et al8 examined the efficacy and acceptance of HIIT in patients with GAD.

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- A total of 33 German adults (24 women) age ≥18 who met DSM-5 criteria for GAD were enrolled in a parallel-group, assessor-blinded RCT. Participants were blinded to the hypotheses of the trial, but not to the intervention.

- Participants were randomized to a HIIT group (engaged in HIIT on a bicycle ergometer every second day within 12 days, with each session lasting 20 minutes and consisting of alternating sessions of 77% to 95% maximum heart rate and <70% maximum heart rate) or a control group of lower-intensity exercise (LIT; consisted of 6 30-minute sessions within 12 days involving stretching and adapted yoga positions with heart rate <70% maximum heart rate).

- Exclusion criteria included severe depression, schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder (BPD), substance use disorder, suicidality, epilepsy, severe respiratory or cardiovascular diseases, and current psychotherapy. The use of medications was allowed if the patient was stable ≥4 weeks prior to the trial and remained stable during the trial.

- The primary outcome of worrying was assessed by the PSWQ. Other assessment tools included the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Anxiety Control Questionnaire, and Screening for Somatoform Symptoms-7 (SOMS-7).

Outcomes

- Baseline PSWQ scores in both groups were >60, indicating “high worriers.”

- Both groups experienced reductions in worrying as measured by PSWQ scores. However, the HIIT group had a larger decrease in worrying compared to the LIT group (P < .02). Post-hoc analyses showed significant reductions in symptom severity from baseline to poststudy (P < .01; d = 0.68), and at 30-day follow-up (P < .01; d = 0.62) in the HIIT group. There was no significant difference in the LIT group from baseline to poststudy or at follow-up.

- Secondary outcome measures included a greater reduction in anxiety and depression as determined by change in HAM-A and HAM-D scores in the HIIT group compared to the LIT group.

- All measures showed improvement in the HIIT group, whereas the LIT group showed improvement in HAM-A and HAM-D scores poststudy and at follow-up, as well as SOMS-7 scores at follow-up.

Conclusions/limitations

- HIIT demonstrated a large treatment effect for treating GAD, including somatic symptoms and worrying.

- HIIT displayed a fast onset of action and low cancellation rate, which suggests it is tolerable.

- This study had a small sample size consisting of participants from only 1 institution, which limits generalizability, and did not look at the long-term effects of the interventions.

5. Amir N, Taboas W, Montero M. Feasibility and dissemination of a computerized home-based treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Behav Res Ther. 2019;120:103446. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2019.103446

Many patients with anxiety disorders do not receive treatment, and logistical factors such as limited time, expertise, and available resources hinder patients from obtaining quality CBT. Attention bias modification (ABM) is a computer-based approach in which patients complete tasks guiding their attention away from threat-relevant cues.21 Applied relaxation psychoeducation (AR-pe) is another empirically supported treatment that can be administered via computer. Amir et al9 examined the feasibility and effectiveness of a home-based computerized regimen of sequenced or simultaneous ABM and AR-pe in patients with GAD.

Study design

- A total of 169 adults age 18 to 65 who met DSM-IV criteria for GAD were randomized into 4 groups: ABM followed by AR-pe, AR-pe followed by ABM, simultaneous ABM and AR-pe, or a clinical monitoring assessment only control group (CM).

- Participants were expected to complete up to 24 30-minute sessions on their home computer over 12 weeks.

- Exclusion criteria included current psychotropic medications/CBT initiated 3 months prior to the study, BD, schizophrenia, or substance use disorder.

- The primary outcome measure was anxiety symptoms as assessed by the HAM-A (remission was defined as a score ≤7 at Week 13). Other measures included the PSWQ, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Sheehan Disability Scale, and Beck Depression Inventory.

- Participants were assessed at Month 3, Month 6, and Month 12 poststudy.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Baseline characteristics did not significantly differ between groups.

- In the active groups, 41% of participants met remission criteria, compared to 19% in the CM group.

- The ABM followed by AR-pe group and the AR-pe followed by ABM group had significant reductions in HAM-A scores (P = .003 and P = .020) compared to the CM group.

- The simultaneous ABM and AR-pe group did not have a significant difference in outcomes compared to the CM group (P = .081).

- On the PSWQ, the CM group had a larger decrease in worry than all active cohorts combined, with follow-up analysis indicating the CM group surpassed the ABM group (P = .019).

Conclusions/limitations

- Sequential delivery of ABM and AR-pe may be a viable, easy-to-access treatment option for patients with GAD who have limited access to other therapies.

- Individuals assigned to receive simultaneous ABM and AR-pe appeared to complete fewer tasks compared to those in the sequential groups, which suggests that participants were less inclined to complete all tasks despite being allowed more time.

- This study did not examine the effects of ABM only or AR-pe only.

- This study was unable to accurately assess home usage of the program.

6. Burke J, Richards D, Timulak L. Helpful and hindering events in internet-delivered cognitive behavioural treatment for generalized anxiety. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2019;47(3):386-399. doi:10.1017/S1352465818000504

Patients with GAD may not be able to obtain adequate treatment due to financial or logistical constraints. Internet-delivered interventions are easily accessible and provide an opportunity for patients who cannot or do not want to seek traditional therapy options. Burke et al10 aimed to better understand the useful and impeding events of internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (iCBT).

Study design

- A total of 36 adults (25 women) age 18 to 45 from an Irish university were randomized to an immediate iCBT treatment group or a delayed access to treatment/waiting list control group. The iCBT program, called Calming Anxiety, involved 6 modules of CBT for GAD.

- Participants initially scored ≥10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7).

- The study employed the Helpful and Hindering Aspects of Therapy (HAT) questionnaire to assess the most useful and impeding events in therapy.

- The data were divided into 4 domains: helpful events, helpful impacts, hindering events, and hindering impacts.

Outcomes

- Of the 8 helpful events identified, the top 3 were psychoeducation, supporter interaction, and monitoring.

- Of the 5 helpful impacts identified, the top 3 were support and validation, applying coping strategies/behavioral change, and clarification, awareness, and insight.

- The 2 identified hindering events were treatment content/form and amount of work/technical issues.

- The 3 identified hindering impacts were frustration/irritation, increased anxiety, and isolation.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- iCBT may be a useful and accessible approach for treating GAD, although there are still hindrances to its use.

- This study was qualitative and did not comment on the efficacy of the applied intervention.

- The benefits of iCBT may differ depending on the patient’s level of computer literacy.

7. Miller CB, Gu J, Henry AL, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a digital CBT intervention for symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized multiple-baseline study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2021;70:101609. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2020.101609

Access to CBT is limited due to cost, dearth of trained therapists, scheduling availability, stigma, and transportation. Digital CBT may help overcome these obstacles. Miller et al11 studied the feasibility and efficacy of a new automated, digital CBT intervention named Daylight.

Study design

- This randomized, multiple-baseline, single-case, experimental trial included 21 adults (20 women) age ≥18 who scored ≥10 on the GAD-7 and screened positive for GAD on MINI version 7 for DSM-5.

- Participants were not taking psychotropic medications or had been on a stable medication regimen for ≥4 weeks.