User login

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

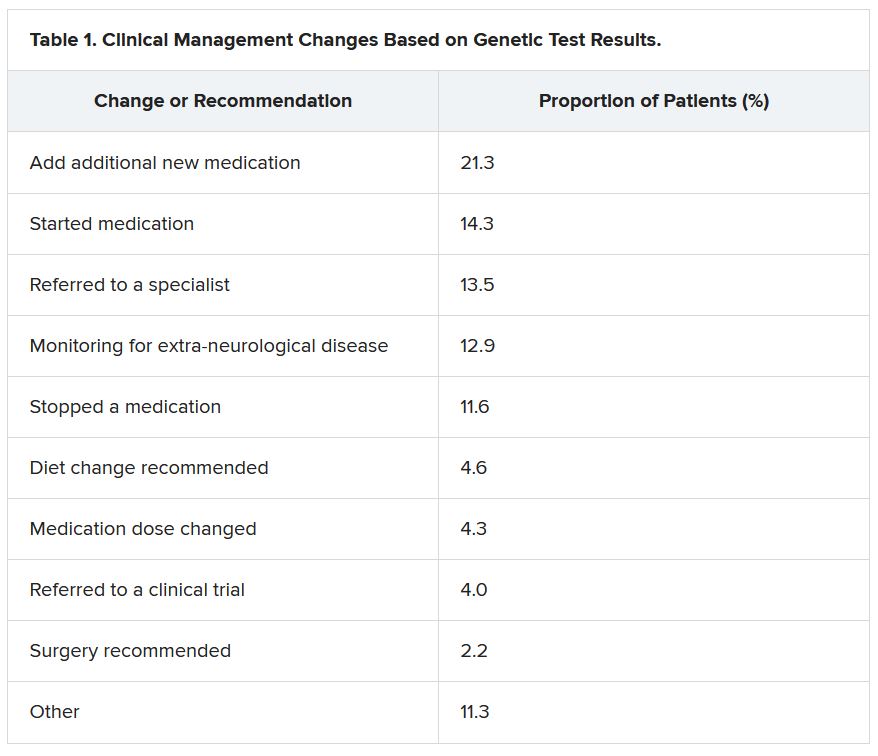

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

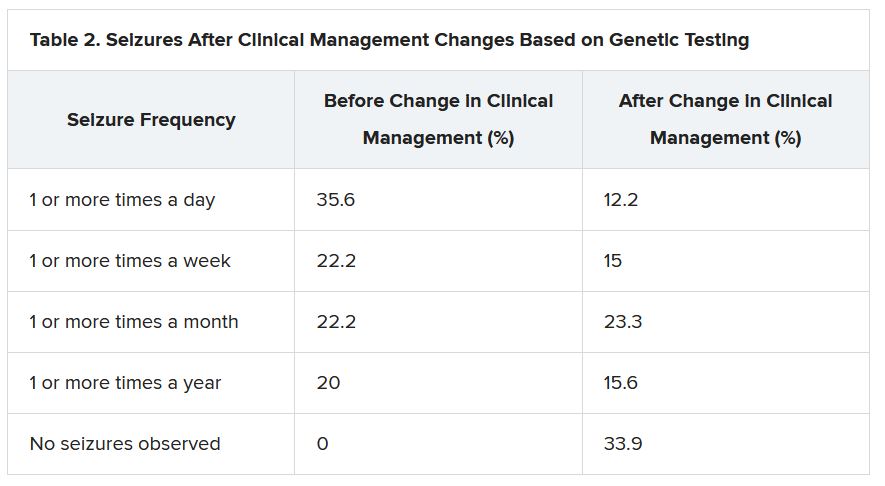

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From WCN 2021