User login

Genital herpes is a common infection caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) or herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). Although life-threatening health consequences of HSV infection after infancy are uncommon, women with genital herpes remain at risk for recurrent symptoms, which can be associated with significant physical and psychosocial distress. These patients also can transmit the disease to their partners and neonates, and have a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of HIV acquisition. In this article, we review the diagnosis and management of genital herpes in pregnant women.

CASE Asymptomatic pregnant patient tests positive for herpes

Sarah is a healthy 32-year-old (G1P0) presenting at 8 weeks’ gestation for her first prenatal visit. She requests HSV testing as she learned that genital herpes is common and it can be transmitted to the baby. You order the HSV-2 IgG assay from your laboratory, which performs the HerpeSelect HSV-2 enzyme immunoassay as the standard test. The test result is positive, with an index value of 2.2 (the manufacturer defines an index value >1.1 as positive). Repeat testing in 4 weeks returns positive results again, with an index value of 2.8.

The patient is distressed at this news. She has no history of genital lesions or symptoms consistent with genital herpes and is worried that her husband has been unfaithful. How would you manage this case?

How prevalent is HSV?

Genital herpes is a chronic viral infection transmitted through close contact with a person who is shedding the virus from genital or oral mucosa. In the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicated an HSV-2 seroprevalence of 16% among persons aged 14 to 49 in 2005–2010, a decline from 21% in 1988–1991.1 The prevalence among women is twice as high as among men, at 20% versus 11%, respectively. Among those with HSV-2, 87% are not aware that they are infected; they are at risk of infecting their partners, however.1

In the same age group, the prevalence of HSV-1 is 54%.2 The seroprevalence of HSV-1 in adolescents declined from 39% in 1999–2004 to 30% in 2005–2010, resulting in a high number of young people who are seronegative at the time of sexual debut. Concurrently, genital HSV-1 has emerged as a frequent cause of first-episode genital herpes, often associated with oral-genital contact during sexual debut.2,3

When evaluating patients for possible genital herpes provide general educational messages regarding HSV infection and obtain a detailed medical and sexual history to determine the best diagnostic approach.

What are the clinical features of genital HSV infection?

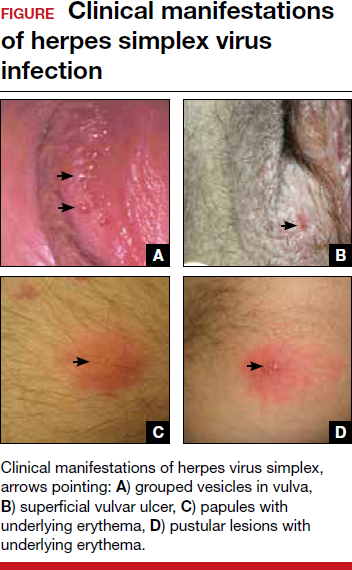

The clinical manifestations of genital herpes vary according to whether the infection is primary, nonprimary first episode, or recurrent.

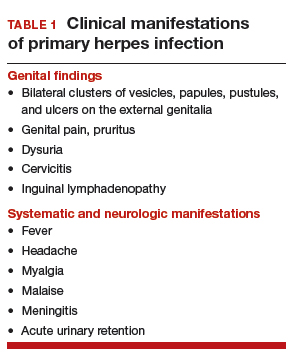

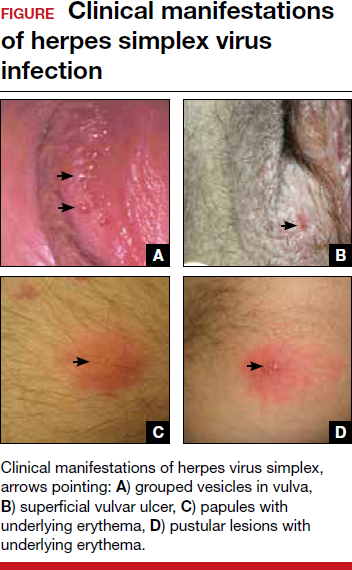

Primary infection. During primary infection,which occurs 4 to 12 days after sexual exposure and in the absence of pre-existing antibodies to HSV-1 or HSV-2, patients may experience genital and systemic symptoms (FIGURE and TABLE 1). Since this infection usually occurs in otherwise healthy people, for many, this is the most severe disease that they have experienced. However, most patients with primary infection develop mild, atypical, or completely asymptomatic presentation and are not diagnosed at the time of HSV acquisition. Whether primary infection is caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2 cannot be differentiated based on the clinical presentation alone.

Nonprimary first episode infection. In a nonprimary infection, newly acquired infection with HSV-1 or HSV-2 occurs in a person with pre-existing antibodies to the other virus. Almost always, this means new HSV-2 infection in a HSV-1 seropositive person, as prior HSV-2 infection appears to protect against HSV-1 acquisition. In general, the clinical presentation of nonprimary infection is somewhat milder and the rate of complications is lower, but clinically the overlap is great, and antibody tests are needed to define whether the patient has primary or nonprimary infection.4

Recurrent genital herpes infection occurs in most patients with genital herpes. The rate of recurrence is low in patients with genital HSV-1 and often high in patients with genital HSV-2 infection. The median number of recurrences is 1 in the first year of genital HSV-1 infection, and many patients will not have any recurrences following the first year. By contrast, in patients with genital HSV-2 infection, the median number of recurrences is 4, and a high rate of recurrences can continue for many years. Prodromal symptoms (localized irritation, paresthesias, and pruritus) can precede recurrences, which usually present with fewer lesions and last a shorter time than primary infection. Recurrent genital lesions tend to heal in approximately 5 to 10 days in the absence of antiviral treatment, and systemic symptoms are uncommon.5

Asymptomatic viral shedding. After resolution of a primary HSV infection, people shed the virus in the genital tract despite symptom absence. Asymptomatic shedding tends to be more frequent and prolonged with primary genital HSV-2 infection compared with HSV-1 infection.6,7 The frequency of HSV shedding is highest in the first year of infection, and decreases subsequently.8 However, it is likely to persist intermittently for many years. Because the natural history is so strikingly different in genital HSV-1 versus HSV-2, identification of the viral type is important for prognostic information.

The first HSV episode does not necessarily indicate a new or recent infection—in about 25% of persons it represents the first recognized genital herpes episode. Additional serologic and virologic evaluation can be pursued to determine if the first episode represents a new infection.

Read about the diagnostic tests for genital HSV.

What diagnostic tests are available for genital herpes?

Most HSV infections are clinically silent. Therefore, laboratory tests are required to diagnose the infection. Even if symptoms are present, diagnoses based only on clinical presentation have a 20% false-positive rate. Always confirm diagnosis by laboratory assay.9 Furthermore, couples that are discordant for HSV-2 by history are often concordant by serologic assays, as the transmission already has occurred but was not recognized. In these cases, the direction of transmission cannot be determined, and stable couples often experience relief learning that they are not discordant.

Related article:

Effective treatment of recurrent bacterial vaginosis

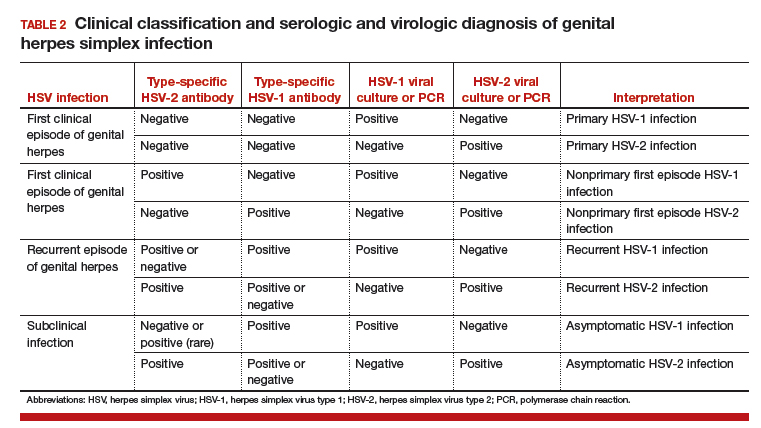

Several laboratory tools for HSV diagnosis based on direct viral detection and antibody detection can be used in clinical settings (TABLE 2). Among patients with symptomatic genital herpes, a sample from the lesion can be used to confirm and identify viral type. Because polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is substantially more sensitive than viral culture and increasingly available it has emerged as the preferred test.9 Viral culture is highly specific (>99%), but sensitivity varies according to collection technique and stage of the lesions. (The test is less sensitive when lesions are healing.)9,10 Antigen detection by immunofluorescence (direct fluorescent antibody) detects HSV from active lesions with high specificity, but sensitivity is low. Cytologic identification of infected cells (using Tzanck or Pap test) has limited utility for diagnosis due to low sensitivity and specificity.9

Type-specific antibodies to HSV develop during the first several weeks after acquisition and persist indefinitely.11 Most accurate type-specific serologic tests are based on detection of glycoprotein G1 and glycoprotein G2 for HSV-1 and HSV-2, respectively.

HerpeSelect HSV-2 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is one of the most commonly used tests in the United States. The manufacturer considers results with index values 1.1 or greater as showing HSV-2 infection. Unfortunately, low positive results, often with a defined index value of 1.1 to 3.5, are frequently false positive. These low positive values should be confirmed with another test, such as Western blot.9

Western blot has been considered the gold standard assay for HSV-1 and HSV-2 antibody detection; this test is available at the University of Washington in Seattle. When comparing the HSV-1 EIA and HSV-2 EIA with the Western blot assay in clinical practice, the estimated sensitivity and specificity are 70.2% and 91.6%, respectively, for HSV-1 and 91.9% and 57.4%, respectively, for HSV-2.12

HerpeSelect HSV-2 Immunoblot testing should not be considered as confirmatory because this assay detects the same antigen as the HSV-2 EIA. Serologic tests based on detection of HSV-IgM should not be used for diagnosis of genital herpes as IgM response can present during a new infection or HSV reactivation and because IgM responses are not type-specific. Clearly, more accurate commercial type-specific antibody tests are needed.

Specific HSV antibodies can take up to 12 weeks to develop. Therefore, repeat serologic testing for patients in whom initial HSV antibody results are negative yet recent genital herpes acquisition is suspected.11 A confirmed positive HSV-2 antibody test indicates anogenital infection, even in a person who lacks genital symptoms. This finding became evident through a study of 53 HSV-2 seropositive patients who lacked a history of genital herpes. Patients were followed for 3 months, and all but 1 developed either virologic or clinical (or both) evidence of genital herpes.13

In the absence of genital or orolabial symptoms among individuals with positive HSV-1, serologic testing cannot distinguish anogenital from orolabial infection. Most of these infections may represent oral HSV-1 infection; however, given increasing occurrence of genital HSV-1 infection, this could also represent a genital infection.

What are the clinical uses of type-specific HSV serology?

Type-specific serologic tests are helpful in diagnosing patients with atypical or asymptomatic infection and managing the care of persons whose sex partners have genital herpes. Serologic testing can be useful to confirm a clinical diagnosis of HSV, to determine whether atypical lesions or symptoms are attributable to HSV, and as part of evaluation for sexually transmitted diseases in select patients. Screening for HSV-1 and HSV-2 in the general population is not supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for several reasons9,10:

- suboptimal performance of commercial HSV antibody tests

- low positive predictive value of these tests in low prevalence HSV settings

- lack of widely available confirmatory testing

- lack of cost-effectiveness

- potential for psychological harm.

Read about treating HSV infection during pregnancy.

Case Continued…

Because Sarah did not have a history of genital herpes, a serum sample was tested by the University of Washington Western blot. The results indicated that Sarah is seronegative for HSV-1 and HSV-2.

Sarah, who is now at 16 weeks’ gestation, returns for evaluation of new genital pain. On examination, she has several shallow ulcerations on the labia and bilateral tender inguinal adenopathy. Her husband recently had cold sores. She is anxious and would like to know if she has genital herpes and if her baby is at risk for HSV infection. You swab the base of a lesion for HSV PCR testing and start antiviral treatment.

Treating HSV infection during pregnancy

Women presenting with a new genital ulcer consistent with HSV should receive empiric antiviral treatment while awaiting confirmatory diagnostic laboratory testing, even during pregnancy. Antiviral therapy with acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir is the backbone of management of most symptomatic patients with herpes. Antiviral drugs can reduce signs and symptoms of first or recurrent genital herpes and can be used for daily suppressive therapy to prevent recurrences. These drugs do not eradicate the infection or alter the risk of frequency or severity after the drug is discontinued.

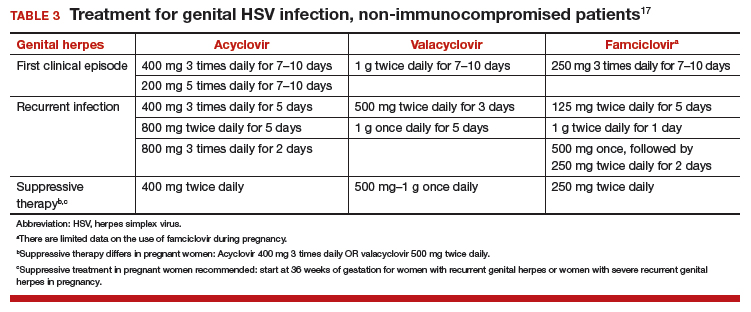

Antiviral advantages/disadvantages. Acyclovir is the least expensive drug, but valacyclovir is the most convenient therapy given its less frequent dosing. Acyclovir and valacyclovir are equally efficacious in treating first-episode genital herpes infection with respect to duration of viral shedding, time of healing, duration of pain, and time to symptom clearance. Two randomized clinical trials showed similar benefits of acyclovir and valacyclovir for suppressive therapy management of genital herpes.14,15 Only 1 study compared the efficacy of famciclovir to valacyclovir for suppression and showed that valacyclovir was more effective.16 The cost of famciclovir is usually higher, and it has the least data on use in pregnant women. Acyclovir therapy can be safely used throughout pregnancy and during breastfeeding.9 Antiviral regimens for the treatment of genital HSV in pregnant and nonpregnant women recommended by the CDC are summarized in TABLE 3.17

Related article:

5 ways to reduce infection risk during pregnancy

Will your patient’s infant develop neonatal herpes infection?

Neonatal herpes is a potentially devastating infection that results from exposure to HSV from the maternal genital tract at vaginal delivery. Most cases occur in infants born to women who lack a history of genital herpes.18 In a large cohort study conducted in Washington State, isolation of HSV at the time of labor was strongly associated with vertical transmission (odds ratio [OR], 346).19 The risk of neonatal herpes increased among women shedding HSV-1 compared with HSV-2 (OR, 16.5). The highest risk of transmission to the neonate is in women who acquire genital herpes in a period close to the delivery (30% to 50% risk of transmission), compared with women with a prenatal history of herpes or who acquired herpes early in pregnancy (about 1% to 3% risk of transmission), most likely due to protective HSV-specific maternal antibodies and lower viral load during reactivation versus primary infection.18

Neonatal HSV-1 infection also has been reported in neonates born to women with primary HSV-1 gingivostomatitis during pregnancy; 70% of these women had oral clinical symptoms during the peripartum period.20 Potential mechanisms are exposure to infected genital secretions, direct maternal hematogenous spread, or oral shedding from close contacts.

Although prenatal HSV screening is not recommended by the CDC or USPSTF, serologic testing could be helpful when identifying appropriate pregnancy management for women with a prior history of HSV infection. It also could be beneficial in identifying women without HSV to guide counseling prevention for HSV acquisition. In patients presenting with active genital lesions, viral-specific diagnostic evaluation should be obtained. In those with a history of laboratory confirmed genital herpes, no additional testing is warranted.

Preventing neonatal herpes

There are no prevention strategies for neonatal herpes in the United States, and the incidence of neonatal herpes has not changed in several decades.10 The current treatment guidelines focus on managing women who may be at risk for HSV acquisition during pregnancy and the management of genital lesions in women during pregnancy.9,10,21

When the partner has HSV. Women who have no history of genital herpes or who are seronegative for HSV-2 should avoid intercourse during the third trimester with a partner known to have genital herpes.9 Those who have no history of orolabial herpes or who are seronegative for HSV-1 and have a seropositive partner should avoid receptive oral-genital contact and genital intercourse.9 Condoms can reduce but not eliminate the risk of HSV transmission; to effectively avoid genital herpes infection, abstinence is recommended.

When the patient has HSV. When managing the care of a pregnant woman with genital herpes evaluate for clinical symptoms and timing of infection or recurrence relative to time of delivery:

- Monitor women with a mild recurrence of HSV during the first 35 weeks of pregnancy without antiviral treatment, as most of the recurrent episodes of genital herpes are short.

- Consider antivirals for women with severe symptoms or multiple recurrences.

- Offer women with a history of genital lesions suppressive antiviral therapy at 36 weeks of gestation until delivery.21

In a meta-analysis of 7 randomized trials, 1,249 women with a history of genital herpes prior to or during pregnancy received prophylaxis with either acyclovir or valacyclovir versus placebo or no treatment at 36 weeks of gestation. Antiviral therapy reduced the risk of HSV recurrence at delivery (relative risk [RR], 0.28), cesarean delivery in those with recurrent genital herpes (RR, 0.3), and asymptomatic shedding at delivery (RR, 0.14).22 No data are available regarding the effectiveness of this approach to prevention of neonatal HSV, and case reports confirm neonatal HSV in infants born to women who received suppressive antiviral therapy at the end of pregnancy.23

When cesarean delivery is warranted. At the time of delivery, ask all women about symptoms of genital herpes, including prodromal symptoms, and examine them for genital lesions. For women with active lesions or prodromal symptoms, offer cesarean delivery at the onset of labor or rupture of membranes—this recommendation is supported by the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.9,21 The protective effect of cesarean delivery was evaluated in a large cohort study that found: among women who were shedding HSV at the time of delivery, neonates born by cesarean delivery were less likely to develop HSV infection compared with those born through vaginal delivery (1.2% vs 7.7%, respectively).19 Cesarean delivery is not indicated in patients with a history of HSV without clinical recurrence or prodrome at delivery, as such women have a very low risk of transmitting the infection to the neonate.24

Avoid transcervical antepartum obstetric procedures to reduce the risk of placenta or membrane HSV infection; however, transabdominal invasive procedures can be performed safely, even in the presence of active genital lesions.21 Intrapartum procedures that can cause fetal skin disruption, such as use of fetal scalp electrode or forceps, are risk factors for HSV transmission and should be avoided in women with a history of genital herpes.

Related articles:

8 common questions about newborn circumcision

Case Resolved

Sarah’s genital lesion PCR results returned positive for HSV-1. She probably acquired the infection from oral-genital sex with her husband who likely has oral HSV-1, given the history of cold sores. You treat Sarah with acyclovir 400 mg 3 times per day for 7 days. At 36 weeks’ gestation, Sarah begins suppressive antiviral therapy until delivery. She spontaneously labors at 39 weeks’ gestation; at that time, she has no genital lesions and she delivers vaginally a healthy baby.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Fanfair RN, Zaidi A, Taylor LD, Xu F, Gottlieb S, Markowitz L. Trends in seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 among non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites aged 14 to 49 years–United States, 1988 to 2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(11):860–864.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, McQuillan GM. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2–United States, 1999-2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(3):325–333.

- Bernstein DI, Bellamy AR, Hook EW, 3rd, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(3):344–351.

- Kimberlin DW, Rouse DJ. Clinical practice. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(19):1970–1977.

- Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, Holmes KK. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98(6):958–972.

- Wald A, Zeh J, Selke S, Ashley RL, Corey L. Virologic characteristics of subclinical and symptomatic genital herpes infections. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(12):770–775.

- Reeves WC, Corey L, Adams HG, Vontver LA, Holmes KK. Risk of recurrence after first episodes of genital herpes. Relation to HSV type and antibody response. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(6):315–319.

- Phipps W, Saracino M, Magaret A, et al. Persistent genital herpes simplex virus-2 shedding years following the first clinical episode. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(2):180–187.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1–137.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al; US Preventive Task Force. Serologic screening for genital herpes infection: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316(23):2525–2530.

- Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. 2007;370(9605):2127–2137.

- Agyemang E, Le QA, Warren T, et al. Performance of commercial enzyme-linked immunoassays 1 (EIA) for diagnosis of herpes simplex virus-1 and herpes simplex virus-2 infection in a clinical setting. Sex Transm Dis. 2017; doi:10.1097/olq.0000000000000689.

- Wald A, Zeh J, Selke S, et al. Reactivation of genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in asymptomatic seropositive persons. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(12):844–850.

- Gupta R, Wald A, Krantz E, et al. Valacyclovir and acyclovir for suppression of shedding of herpes simplex virus in the genital tract. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(8):1374–1381.

- Reitano M, Tyring S, Lang W, et al. Valaciclovir for the suppression of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection: a large-scale dose range-finding study. International Valaciclovir HSV Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(3): 603–610.

- Wald A, Selke S, Warren T, et al. Comparative efficacy of famciclovir and valacyclovir for suppression of recurrent genital herpes and viral shedding. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(9):529–533.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015 [published correction appears in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(33):924]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1–137.

- Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1376–1385.

- Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, Selke S, Zeh J, Corey L. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA. 2003;289(2):203–209.

- Healy SA, Mohan KM, Melvin AJ, Wald A. Primary maternal herpes simplex virus-1 gingivostomatitis during pregnancy and neonatal herpes: case series and literature review. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2012;1(4):299–305.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecoloigsts Committee on Practice Bulletins. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 82: Management of herpes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(6):1489–1498.

- Hollier LM, Wendel GD. Third trimester antiviral prophylaxis for preventing maternal genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) recurrences and neonatal infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(1):CD004946.

- Pinninti SG, Angara R, Feja KN, et al. Neonatal herpes disease following maternal antenatal antiviral suppressive therapy: a multicenter case series. J Pediatr. 2012;161(1):134–138.e1–e3.

- Vontver LA, Hickok DE, Brown Z, Reid L, Corey L. Recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection in pregnancy: infant outcome and frequency of asymptomatic recurrences. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1982;143(1):75–84.

Genital herpes is a common infection caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) or herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). Although life-threatening health consequences of HSV infection after infancy are uncommon, women with genital herpes remain at risk for recurrent symptoms, which can be associated with significant physical and psychosocial distress. These patients also can transmit the disease to their partners and neonates, and have a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of HIV acquisition. In this article, we review the diagnosis and management of genital herpes in pregnant women.

CASE Asymptomatic pregnant patient tests positive for herpes

Sarah is a healthy 32-year-old (G1P0) presenting at 8 weeks’ gestation for her first prenatal visit. She requests HSV testing as she learned that genital herpes is common and it can be transmitted to the baby. You order the HSV-2 IgG assay from your laboratory, which performs the HerpeSelect HSV-2 enzyme immunoassay as the standard test. The test result is positive, with an index value of 2.2 (the manufacturer defines an index value >1.1 as positive). Repeat testing in 4 weeks returns positive results again, with an index value of 2.8.

The patient is distressed at this news. She has no history of genital lesions or symptoms consistent with genital herpes and is worried that her husband has been unfaithful. How would you manage this case?

How prevalent is HSV?

Genital herpes is a chronic viral infection transmitted through close contact with a person who is shedding the virus from genital or oral mucosa. In the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicated an HSV-2 seroprevalence of 16% among persons aged 14 to 49 in 2005–2010, a decline from 21% in 1988–1991.1 The prevalence among women is twice as high as among men, at 20% versus 11%, respectively. Among those with HSV-2, 87% are not aware that they are infected; they are at risk of infecting their partners, however.1

In the same age group, the prevalence of HSV-1 is 54%.2 The seroprevalence of HSV-1 in adolescents declined from 39% in 1999–2004 to 30% in 2005–2010, resulting in a high number of young people who are seronegative at the time of sexual debut. Concurrently, genital HSV-1 has emerged as a frequent cause of first-episode genital herpes, often associated with oral-genital contact during sexual debut.2,3

When evaluating patients for possible genital herpes provide general educational messages regarding HSV infection and obtain a detailed medical and sexual history to determine the best diagnostic approach.

What are the clinical features of genital HSV infection?

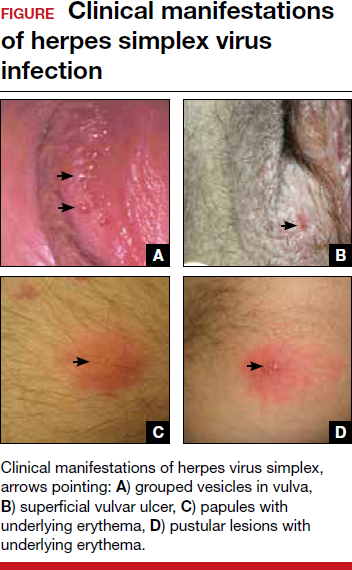

The clinical manifestations of genital herpes vary according to whether the infection is primary, nonprimary first episode, or recurrent.

Primary infection. During primary infection,which occurs 4 to 12 days after sexual exposure and in the absence of pre-existing antibodies to HSV-1 or HSV-2, patients may experience genital and systemic symptoms (FIGURE and TABLE 1). Since this infection usually occurs in otherwise healthy people, for many, this is the most severe disease that they have experienced. However, most patients with primary infection develop mild, atypical, or completely asymptomatic presentation and are not diagnosed at the time of HSV acquisition. Whether primary infection is caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2 cannot be differentiated based on the clinical presentation alone.

Nonprimary first episode infection. In a nonprimary infection, newly acquired infection with HSV-1 or HSV-2 occurs in a person with pre-existing antibodies to the other virus. Almost always, this means new HSV-2 infection in a HSV-1 seropositive person, as prior HSV-2 infection appears to protect against HSV-1 acquisition. In general, the clinical presentation of nonprimary infection is somewhat milder and the rate of complications is lower, but clinically the overlap is great, and antibody tests are needed to define whether the patient has primary or nonprimary infection.4

Recurrent genital herpes infection occurs in most patients with genital herpes. The rate of recurrence is low in patients with genital HSV-1 and often high in patients with genital HSV-2 infection. The median number of recurrences is 1 in the first year of genital HSV-1 infection, and many patients will not have any recurrences following the first year. By contrast, in patients with genital HSV-2 infection, the median number of recurrences is 4, and a high rate of recurrences can continue for many years. Prodromal symptoms (localized irritation, paresthesias, and pruritus) can precede recurrences, which usually present with fewer lesions and last a shorter time than primary infection. Recurrent genital lesions tend to heal in approximately 5 to 10 days in the absence of antiviral treatment, and systemic symptoms are uncommon.5

Asymptomatic viral shedding. After resolution of a primary HSV infection, people shed the virus in the genital tract despite symptom absence. Asymptomatic shedding tends to be more frequent and prolonged with primary genital HSV-2 infection compared with HSV-1 infection.6,7 The frequency of HSV shedding is highest in the first year of infection, and decreases subsequently.8 However, it is likely to persist intermittently for many years. Because the natural history is so strikingly different in genital HSV-1 versus HSV-2, identification of the viral type is important for prognostic information.

The first HSV episode does not necessarily indicate a new or recent infection—in about 25% of persons it represents the first recognized genital herpes episode. Additional serologic and virologic evaluation can be pursued to determine if the first episode represents a new infection.

Read about the diagnostic tests for genital HSV.

What diagnostic tests are available for genital herpes?

Most HSV infections are clinically silent. Therefore, laboratory tests are required to diagnose the infection. Even if symptoms are present, diagnoses based only on clinical presentation have a 20% false-positive rate. Always confirm diagnosis by laboratory assay.9 Furthermore, couples that are discordant for HSV-2 by history are often concordant by serologic assays, as the transmission already has occurred but was not recognized. In these cases, the direction of transmission cannot be determined, and stable couples often experience relief learning that they are not discordant.

Related article:

Effective treatment of recurrent bacterial vaginosis

Several laboratory tools for HSV diagnosis based on direct viral detection and antibody detection can be used in clinical settings (TABLE 2). Among patients with symptomatic genital herpes, a sample from the lesion can be used to confirm and identify viral type. Because polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is substantially more sensitive than viral culture and increasingly available it has emerged as the preferred test.9 Viral culture is highly specific (>99%), but sensitivity varies according to collection technique and stage of the lesions. (The test is less sensitive when lesions are healing.)9,10 Antigen detection by immunofluorescence (direct fluorescent antibody) detects HSV from active lesions with high specificity, but sensitivity is low. Cytologic identification of infected cells (using Tzanck or Pap test) has limited utility for diagnosis due to low sensitivity and specificity.9

Type-specific antibodies to HSV develop during the first several weeks after acquisition and persist indefinitely.11 Most accurate type-specific serologic tests are based on detection of glycoprotein G1 and glycoprotein G2 for HSV-1 and HSV-2, respectively.

HerpeSelect HSV-2 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is one of the most commonly used tests in the United States. The manufacturer considers results with index values 1.1 or greater as showing HSV-2 infection. Unfortunately, low positive results, often with a defined index value of 1.1 to 3.5, are frequently false positive. These low positive values should be confirmed with another test, such as Western blot.9

Western blot has been considered the gold standard assay for HSV-1 and HSV-2 antibody detection; this test is available at the University of Washington in Seattle. When comparing the HSV-1 EIA and HSV-2 EIA with the Western blot assay in clinical practice, the estimated sensitivity and specificity are 70.2% and 91.6%, respectively, for HSV-1 and 91.9% and 57.4%, respectively, for HSV-2.12

HerpeSelect HSV-2 Immunoblot testing should not be considered as confirmatory because this assay detects the same antigen as the HSV-2 EIA. Serologic tests based on detection of HSV-IgM should not be used for diagnosis of genital herpes as IgM response can present during a new infection or HSV reactivation and because IgM responses are not type-specific. Clearly, more accurate commercial type-specific antibody tests are needed.

Specific HSV antibodies can take up to 12 weeks to develop. Therefore, repeat serologic testing for patients in whom initial HSV antibody results are negative yet recent genital herpes acquisition is suspected.11 A confirmed positive HSV-2 antibody test indicates anogenital infection, even in a person who lacks genital symptoms. This finding became evident through a study of 53 HSV-2 seropositive patients who lacked a history of genital herpes. Patients were followed for 3 months, and all but 1 developed either virologic or clinical (or both) evidence of genital herpes.13

In the absence of genital or orolabial symptoms among individuals with positive HSV-1, serologic testing cannot distinguish anogenital from orolabial infection. Most of these infections may represent oral HSV-1 infection; however, given increasing occurrence of genital HSV-1 infection, this could also represent a genital infection.

What are the clinical uses of type-specific HSV serology?

Type-specific serologic tests are helpful in diagnosing patients with atypical or asymptomatic infection and managing the care of persons whose sex partners have genital herpes. Serologic testing can be useful to confirm a clinical diagnosis of HSV, to determine whether atypical lesions or symptoms are attributable to HSV, and as part of evaluation for sexually transmitted diseases in select patients. Screening for HSV-1 and HSV-2 in the general population is not supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for several reasons9,10:

- suboptimal performance of commercial HSV antibody tests

- low positive predictive value of these tests in low prevalence HSV settings

- lack of widely available confirmatory testing

- lack of cost-effectiveness

- potential for psychological harm.

Read about treating HSV infection during pregnancy.

Case Continued…

Because Sarah did not have a history of genital herpes, a serum sample was tested by the University of Washington Western blot. The results indicated that Sarah is seronegative for HSV-1 and HSV-2.

Sarah, who is now at 16 weeks’ gestation, returns for evaluation of new genital pain. On examination, she has several shallow ulcerations on the labia and bilateral tender inguinal adenopathy. Her husband recently had cold sores. She is anxious and would like to know if she has genital herpes and if her baby is at risk for HSV infection. You swab the base of a lesion for HSV PCR testing and start antiviral treatment.

Treating HSV infection during pregnancy

Women presenting with a new genital ulcer consistent with HSV should receive empiric antiviral treatment while awaiting confirmatory diagnostic laboratory testing, even during pregnancy. Antiviral therapy with acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir is the backbone of management of most symptomatic patients with herpes. Antiviral drugs can reduce signs and symptoms of first or recurrent genital herpes and can be used for daily suppressive therapy to prevent recurrences. These drugs do not eradicate the infection or alter the risk of frequency or severity after the drug is discontinued.

Antiviral advantages/disadvantages. Acyclovir is the least expensive drug, but valacyclovir is the most convenient therapy given its less frequent dosing. Acyclovir and valacyclovir are equally efficacious in treating first-episode genital herpes infection with respect to duration of viral shedding, time of healing, duration of pain, and time to symptom clearance. Two randomized clinical trials showed similar benefits of acyclovir and valacyclovir for suppressive therapy management of genital herpes.14,15 Only 1 study compared the efficacy of famciclovir to valacyclovir for suppression and showed that valacyclovir was more effective.16 The cost of famciclovir is usually higher, and it has the least data on use in pregnant women. Acyclovir therapy can be safely used throughout pregnancy and during breastfeeding.9 Antiviral regimens for the treatment of genital HSV in pregnant and nonpregnant women recommended by the CDC are summarized in TABLE 3.17

Related article:

5 ways to reduce infection risk during pregnancy

Will your patient’s infant develop neonatal herpes infection?

Neonatal herpes is a potentially devastating infection that results from exposure to HSV from the maternal genital tract at vaginal delivery. Most cases occur in infants born to women who lack a history of genital herpes.18 In a large cohort study conducted in Washington State, isolation of HSV at the time of labor was strongly associated with vertical transmission (odds ratio [OR], 346).19 The risk of neonatal herpes increased among women shedding HSV-1 compared with HSV-2 (OR, 16.5). The highest risk of transmission to the neonate is in women who acquire genital herpes in a period close to the delivery (30% to 50% risk of transmission), compared with women with a prenatal history of herpes or who acquired herpes early in pregnancy (about 1% to 3% risk of transmission), most likely due to protective HSV-specific maternal antibodies and lower viral load during reactivation versus primary infection.18

Neonatal HSV-1 infection also has been reported in neonates born to women with primary HSV-1 gingivostomatitis during pregnancy; 70% of these women had oral clinical symptoms during the peripartum period.20 Potential mechanisms are exposure to infected genital secretions, direct maternal hematogenous spread, or oral shedding from close contacts.

Although prenatal HSV screening is not recommended by the CDC or USPSTF, serologic testing could be helpful when identifying appropriate pregnancy management for women with a prior history of HSV infection. It also could be beneficial in identifying women without HSV to guide counseling prevention for HSV acquisition. In patients presenting with active genital lesions, viral-specific diagnostic evaluation should be obtained. In those with a history of laboratory confirmed genital herpes, no additional testing is warranted.

Preventing neonatal herpes

There are no prevention strategies for neonatal herpes in the United States, and the incidence of neonatal herpes has not changed in several decades.10 The current treatment guidelines focus on managing women who may be at risk for HSV acquisition during pregnancy and the management of genital lesions in women during pregnancy.9,10,21

When the partner has HSV. Women who have no history of genital herpes or who are seronegative for HSV-2 should avoid intercourse during the third trimester with a partner known to have genital herpes.9 Those who have no history of orolabial herpes or who are seronegative for HSV-1 and have a seropositive partner should avoid receptive oral-genital contact and genital intercourse.9 Condoms can reduce but not eliminate the risk of HSV transmission; to effectively avoid genital herpes infection, abstinence is recommended.

When the patient has HSV. When managing the care of a pregnant woman with genital herpes evaluate for clinical symptoms and timing of infection or recurrence relative to time of delivery:

- Monitor women with a mild recurrence of HSV during the first 35 weeks of pregnancy without antiviral treatment, as most of the recurrent episodes of genital herpes are short.

- Consider antivirals for women with severe symptoms or multiple recurrences.

- Offer women with a history of genital lesions suppressive antiviral therapy at 36 weeks of gestation until delivery.21

In a meta-analysis of 7 randomized trials, 1,249 women with a history of genital herpes prior to or during pregnancy received prophylaxis with either acyclovir or valacyclovir versus placebo or no treatment at 36 weeks of gestation. Antiviral therapy reduced the risk of HSV recurrence at delivery (relative risk [RR], 0.28), cesarean delivery in those with recurrent genital herpes (RR, 0.3), and asymptomatic shedding at delivery (RR, 0.14).22 No data are available regarding the effectiveness of this approach to prevention of neonatal HSV, and case reports confirm neonatal HSV in infants born to women who received suppressive antiviral therapy at the end of pregnancy.23

When cesarean delivery is warranted. At the time of delivery, ask all women about symptoms of genital herpes, including prodromal symptoms, and examine them for genital lesions. For women with active lesions or prodromal symptoms, offer cesarean delivery at the onset of labor or rupture of membranes—this recommendation is supported by the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.9,21 The protective effect of cesarean delivery was evaluated in a large cohort study that found: among women who were shedding HSV at the time of delivery, neonates born by cesarean delivery were less likely to develop HSV infection compared with those born through vaginal delivery (1.2% vs 7.7%, respectively).19 Cesarean delivery is not indicated in patients with a history of HSV without clinical recurrence or prodrome at delivery, as such women have a very low risk of transmitting the infection to the neonate.24

Avoid transcervical antepartum obstetric procedures to reduce the risk of placenta or membrane HSV infection; however, transabdominal invasive procedures can be performed safely, even in the presence of active genital lesions.21 Intrapartum procedures that can cause fetal skin disruption, such as use of fetal scalp electrode or forceps, are risk factors for HSV transmission and should be avoided in women with a history of genital herpes.

Related articles:

8 common questions about newborn circumcision

Case Resolved

Sarah’s genital lesion PCR results returned positive for HSV-1. She probably acquired the infection from oral-genital sex with her husband who likely has oral HSV-1, given the history of cold sores. You treat Sarah with acyclovir 400 mg 3 times per day for 7 days. At 36 weeks’ gestation, Sarah begins suppressive antiviral therapy until delivery. She spontaneously labors at 39 weeks’ gestation; at that time, she has no genital lesions and she delivers vaginally a healthy baby.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Genital herpes is a common infection caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) or herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). Although life-threatening health consequences of HSV infection after infancy are uncommon, women with genital herpes remain at risk for recurrent symptoms, which can be associated with significant physical and psychosocial distress. These patients also can transmit the disease to their partners and neonates, and have a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of HIV acquisition. In this article, we review the diagnosis and management of genital herpes in pregnant women.

CASE Asymptomatic pregnant patient tests positive for herpes

Sarah is a healthy 32-year-old (G1P0) presenting at 8 weeks’ gestation for her first prenatal visit. She requests HSV testing as she learned that genital herpes is common and it can be transmitted to the baby. You order the HSV-2 IgG assay from your laboratory, which performs the HerpeSelect HSV-2 enzyme immunoassay as the standard test. The test result is positive, with an index value of 2.2 (the manufacturer defines an index value >1.1 as positive). Repeat testing in 4 weeks returns positive results again, with an index value of 2.8.

The patient is distressed at this news. She has no history of genital lesions or symptoms consistent with genital herpes and is worried that her husband has been unfaithful. How would you manage this case?

How prevalent is HSV?

Genital herpes is a chronic viral infection transmitted through close contact with a person who is shedding the virus from genital or oral mucosa. In the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicated an HSV-2 seroprevalence of 16% among persons aged 14 to 49 in 2005–2010, a decline from 21% in 1988–1991.1 The prevalence among women is twice as high as among men, at 20% versus 11%, respectively. Among those with HSV-2, 87% are not aware that they are infected; they are at risk of infecting their partners, however.1

In the same age group, the prevalence of HSV-1 is 54%.2 The seroprevalence of HSV-1 in adolescents declined from 39% in 1999–2004 to 30% in 2005–2010, resulting in a high number of young people who are seronegative at the time of sexual debut. Concurrently, genital HSV-1 has emerged as a frequent cause of first-episode genital herpes, often associated with oral-genital contact during sexual debut.2,3

When evaluating patients for possible genital herpes provide general educational messages regarding HSV infection and obtain a detailed medical and sexual history to determine the best diagnostic approach.

What are the clinical features of genital HSV infection?

The clinical manifestations of genital herpes vary according to whether the infection is primary, nonprimary first episode, or recurrent.

Primary infection. During primary infection,which occurs 4 to 12 days after sexual exposure and in the absence of pre-existing antibodies to HSV-1 or HSV-2, patients may experience genital and systemic symptoms (FIGURE and TABLE 1). Since this infection usually occurs in otherwise healthy people, for many, this is the most severe disease that they have experienced. However, most patients with primary infection develop mild, atypical, or completely asymptomatic presentation and are not diagnosed at the time of HSV acquisition. Whether primary infection is caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2 cannot be differentiated based on the clinical presentation alone.

Nonprimary first episode infection. In a nonprimary infection, newly acquired infection with HSV-1 or HSV-2 occurs in a person with pre-existing antibodies to the other virus. Almost always, this means new HSV-2 infection in a HSV-1 seropositive person, as prior HSV-2 infection appears to protect against HSV-1 acquisition. In general, the clinical presentation of nonprimary infection is somewhat milder and the rate of complications is lower, but clinically the overlap is great, and antibody tests are needed to define whether the patient has primary or nonprimary infection.4

Recurrent genital herpes infection occurs in most patients with genital herpes. The rate of recurrence is low in patients with genital HSV-1 and often high in patients with genital HSV-2 infection. The median number of recurrences is 1 in the first year of genital HSV-1 infection, and many patients will not have any recurrences following the first year. By contrast, in patients with genital HSV-2 infection, the median number of recurrences is 4, and a high rate of recurrences can continue for many years. Prodromal symptoms (localized irritation, paresthesias, and pruritus) can precede recurrences, which usually present with fewer lesions and last a shorter time than primary infection. Recurrent genital lesions tend to heal in approximately 5 to 10 days in the absence of antiviral treatment, and systemic symptoms are uncommon.5

Asymptomatic viral shedding. After resolution of a primary HSV infection, people shed the virus in the genital tract despite symptom absence. Asymptomatic shedding tends to be more frequent and prolonged with primary genital HSV-2 infection compared with HSV-1 infection.6,7 The frequency of HSV shedding is highest in the first year of infection, and decreases subsequently.8 However, it is likely to persist intermittently for many years. Because the natural history is so strikingly different in genital HSV-1 versus HSV-2, identification of the viral type is important for prognostic information.

The first HSV episode does not necessarily indicate a new or recent infection—in about 25% of persons it represents the first recognized genital herpes episode. Additional serologic and virologic evaluation can be pursued to determine if the first episode represents a new infection.

Read about the diagnostic tests for genital HSV.

What diagnostic tests are available for genital herpes?

Most HSV infections are clinically silent. Therefore, laboratory tests are required to diagnose the infection. Even if symptoms are present, diagnoses based only on clinical presentation have a 20% false-positive rate. Always confirm diagnosis by laboratory assay.9 Furthermore, couples that are discordant for HSV-2 by history are often concordant by serologic assays, as the transmission already has occurred but was not recognized. In these cases, the direction of transmission cannot be determined, and stable couples often experience relief learning that they are not discordant.

Related article:

Effective treatment of recurrent bacterial vaginosis

Several laboratory tools for HSV diagnosis based on direct viral detection and antibody detection can be used in clinical settings (TABLE 2). Among patients with symptomatic genital herpes, a sample from the lesion can be used to confirm and identify viral type. Because polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is substantially more sensitive than viral culture and increasingly available it has emerged as the preferred test.9 Viral culture is highly specific (>99%), but sensitivity varies according to collection technique and stage of the lesions. (The test is less sensitive when lesions are healing.)9,10 Antigen detection by immunofluorescence (direct fluorescent antibody) detects HSV from active lesions with high specificity, but sensitivity is low. Cytologic identification of infected cells (using Tzanck or Pap test) has limited utility for diagnosis due to low sensitivity and specificity.9

Type-specific antibodies to HSV develop during the first several weeks after acquisition and persist indefinitely.11 Most accurate type-specific serologic tests are based on detection of glycoprotein G1 and glycoprotein G2 for HSV-1 and HSV-2, respectively.

HerpeSelect HSV-2 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is one of the most commonly used tests in the United States. The manufacturer considers results with index values 1.1 or greater as showing HSV-2 infection. Unfortunately, low positive results, often with a defined index value of 1.1 to 3.5, are frequently false positive. These low positive values should be confirmed with another test, such as Western blot.9

Western blot has been considered the gold standard assay for HSV-1 and HSV-2 antibody detection; this test is available at the University of Washington in Seattle. When comparing the HSV-1 EIA and HSV-2 EIA with the Western blot assay in clinical practice, the estimated sensitivity and specificity are 70.2% and 91.6%, respectively, for HSV-1 and 91.9% and 57.4%, respectively, for HSV-2.12

HerpeSelect HSV-2 Immunoblot testing should not be considered as confirmatory because this assay detects the same antigen as the HSV-2 EIA. Serologic tests based on detection of HSV-IgM should not be used for diagnosis of genital herpes as IgM response can present during a new infection or HSV reactivation and because IgM responses are not type-specific. Clearly, more accurate commercial type-specific antibody tests are needed.

Specific HSV antibodies can take up to 12 weeks to develop. Therefore, repeat serologic testing for patients in whom initial HSV antibody results are negative yet recent genital herpes acquisition is suspected.11 A confirmed positive HSV-2 antibody test indicates anogenital infection, even in a person who lacks genital symptoms. This finding became evident through a study of 53 HSV-2 seropositive patients who lacked a history of genital herpes. Patients were followed for 3 months, and all but 1 developed either virologic or clinical (or both) evidence of genital herpes.13

In the absence of genital or orolabial symptoms among individuals with positive HSV-1, serologic testing cannot distinguish anogenital from orolabial infection. Most of these infections may represent oral HSV-1 infection; however, given increasing occurrence of genital HSV-1 infection, this could also represent a genital infection.

What are the clinical uses of type-specific HSV serology?

Type-specific serologic tests are helpful in diagnosing patients with atypical or asymptomatic infection and managing the care of persons whose sex partners have genital herpes. Serologic testing can be useful to confirm a clinical diagnosis of HSV, to determine whether atypical lesions or symptoms are attributable to HSV, and as part of evaluation for sexually transmitted diseases in select patients. Screening for HSV-1 and HSV-2 in the general population is not supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for several reasons9,10:

- suboptimal performance of commercial HSV antibody tests

- low positive predictive value of these tests in low prevalence HSV settings

- lack of widely available confirmatory testing

- lack of cost-effectiveness

- potential for psychological harm.

Read about treating HSV infection during pregnancy.

Case Continued…

Because Sarah did not have a history of genital herpes, a serum sample was tested by the University of Washington Western blot. The results indicated that Sarah is seronegative for HSV-1 and HSV-2.

Sarah, who is now at 16 weeks’ gestation, returns for evaluation of new genital pain. On examination, she has several shallow ulcerations on the labia and bilateral tender inguinal adenopathy. Her husband recently had cold sores. She is anxious and would like to know if she has genital herpes and if her baby is at risk for HSV infection. You swab the base of a lesion for HSV PCR testing and start antiviral treatment.

Treating HSV infection during pregnancy

Women presenting with a new genital ulcer consistent with HSV should receive empiric antiviral treatment while awaiting confirmatory diagnostic laboratory testing, even during pregnancy. Antiviral therapy with acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir is the backbone of management of most symptomatic patients with herpes. Antiviral drugs can reduce signs and symptoms of first or recurrent genital herpes and can be used for daily suppressive therapy to prevent recurrences. These drugs do not eradicate the infection or alter the risk of frequency or severity after the drug is discontinued.

Antiviral advantages/disadvantages. Acyclovir is the least expensive drug, but valacyclovir is the most convenient therapy given its less frequent dosing. Acyclovir and valacyclovir are equally efficacious in treating first-episode genital herpes infection with respect to duration of viral shedding, time of healing, duration of pain, and time to symptom clearance. Two randomized clinical trials showed similar benefits of acyclovir and valacyclovir for suppressive therapy management of genital herpes.14,15 Only 1 study compared the efficacy of famciclovir to valacyclovir for suppression and showed that valacyclovir was more effective.16 The cost of famciclovir is usually higher, and it has the least data on use in pregnant women. Acyclovir therapy can be safely used throughout pregnancy and during breastfeeding.9 Antiviral regimens for the treatment of genital HSV in pregnant and nonpregnant women recommended by the CDC are summarized in TABLE 3.17

Related article:

5 ways to reduce infection risk during pregnancy

Will your patient’s infant develop neonatal herpes infection?

Neonatal herpes is a potentially devastating infection that results from exposure to HSV from the maternal genital tract at vaginal delivery. Most cases occur in infants born to women who lack a history of genital herpes.18 In a large cohort study conducted in Washington State, isolation of HSV at the time of labor was strongly associated with vertical transmission (odds ratio [OR], 346).19 The risk of neonatal herpes increased among women shedding HSV-1 compared with HSV-2 (OR, 16.5). The highest risk of transmission to the neonate is in women who acquire genital herpes in a period close to the delivery (30% to 50% risk of transmission), compared with women with a prenatal history of herpes or who acquired herpes early in pregnancy (about 1% to 3% risk of transmission), most likely due to protective HSV-specific maternal antibodies and lower viral load during reactivation versus primary infection.18

Neonatal HSV-1 infection also has been reported in neonates born to women with primary HSV-1 gingivostomatitis during pregnancy; 70% of these women had oral clinical symptoms during the peripartum period.20 Potential mechanisms are exposure to infected genital secretions, direct maternal hematogenous spread, or oral shedding from close contacts.

Although prenatal HSV screening is not recommended by the CDC or USPSTF, serologic testing could be helpful when identifying appropriate pregnancy management for women with a prior history of HSV infection. It also could be beneficial in identifying women without HSV to guide counseling prevention for HSV acquisition. In patients presenting with active genital lesions, viral-specific diagnostic evaluation should be obtained. In those with a history of laboratory confirmed genital herpes, no additional testing is warranted.

Preventing neonatal herpes

There are no prevention strategies for neonatal herpes in the United States, and the incidence of neonatal herpes has not changed in several decades.10 The current treatment guidelines focus on managing women who may be at risk for HSV acquisition during pregnancy and the management of genital lesions in women during pregnancy.9,10,21

When the partner has HSV. Women who have no history of genital herpes or who are seronegative for HSV-2 should avoid intercourse during the third trimester with a partner known to have genital herpes.9 Those who have no history of orolabial herpes or who are seronegative for HSV-1 and have a seropositive partner should avoid receptive oral-genital contact and genital intercourse.9 Condoms can reduce but not eliminate the risk of HSV transmission; to effectively avoid genital herpes infection, abstinence is recommended.

When the patient has HSV. When managing the care of a pregnant woman with genital herpes evaluate for clinical symptoms and timing of infection or recurrence relative to time of delivery:

- Monitor women with a mild recurrence of HSV during the first 35 weeks of pregnancy without antiviral treatment, as most of the recurrent episodes of genital herpes are short.

- Consider antivirals for women with severe symptoms or multiple recurrences.

- Offer women with a history of genital lesions suppressive antiviral therapy at 36 weeks of gestation until delivery.21

In a meta-analysis of 7 randomized trials, 1,249 women with a history of genital herpes prior to or during pregnancy received prophylaxis with either acyclovir or valacyclovir versus placebo or no treatment at 36 weeks of gestation. Antiviral therapy reduced the risk of HSV recurrence at delivery (relative risk [RR], 0.28), cesarean delivery in those with recurrent genital herpes (RR, 0.3), and asymptomatic shedding at delivery (RR, 0.14).22 No data are available regarding the effectiveness of this approach to prevention of neonatal HSV, and case reports confirm neonatal HSV in infants born to women who received suppressive antiviral therapy at the end of pregnancy.23

When cesarean delivery is warranted. At the time of delivery, ask all women about symptoms of genital herpes, including prodromal symptoms, and examine them for genital lesions. For women with active lesions or prodromal symptoms, offer cesarean delivery at the onset of labor or rupture of membranes—this recommendation is supported by the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.9,21 The protective effect of cesarean delivery was evaluated in a large cohort study that found: among women who were shedding HSV at the time of delivery, neonates born by cesarean delivery were less likely to develop HSV infection compared with those born through vaginal delivery (1.2% vs 7.7%, respectively).19 Cesarean delivery is not indicated in patients with a history of HSV without clinical recurrence or prodrome at delivery, as such women have a very low risk of transmitting the infection to the neonate.24

Avoid transcervical antepartum obstetric procedures to reduce the risk of placenta or membrane HSV infection; however, transabdominal invasive procedures can be performed safely, even in the presence of active genital lesions.21 Intrapartum procedures that can cause fetal skin disruption, such as use of fetal scalp electrode or forceps, are risk factors for HSV transmission and should be avoided in women with a history of genital herpes.

Related articles:

8 common questions about newborn circumcision

Case Resolved

Sarah’s genital lesion PCR results returned positive for HSV-1. She probably acquired the infection from oral-genital sex with her husband who likely has oral HSV-1, given the history of cold sores. You treat Sarah with acyclovir 400 mg 3 times per day for 7 days. At 36 weeks’ gestation, Sarah begins suppressive antiviral therapy until delivery. She spontaneously labors at 39 weeks’ gestation; at that time, she has no genital lesions and she delivers vaginally a healthy baby.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Fanfair RN, Zaidi A, Taylor LD, Xu F, Gottlieb S, Markowitz L. Trends in seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 among non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites aged 14 to 49 years–United States, 1988 to 2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(11):860–864.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, McQuillan GM. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2–United States, 1999-2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(3):325–333.

- Bernstein DI, Bellamy AR, Hook EW, 3rd, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(3):344–351.

- Kimberlin DW, Rouse DJ. Clinical practice. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(19):1970–1977.

- Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, Holmes KK. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98(6):958–972.

- Wald A, Zeh J, Selke S, Ashley RL, Corey L. Virologic characteristics of subclinical and symptomatic genital herpes infections. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(12):770–775.

- Reeves WC, Corey L, Adams HG, Vontver LA, Holmes KK. Risk of recurrence after first episodes of genital herpes. Relation to HSV type and antibody response. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(6):315–319.

- Phipps W, Saracino M, Magaret A, et al. Persistent genital herpes simplex virus-2 shedding years following the first clinical episode. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(2):180–187.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1–137.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al; US Preventive Task Force. Serologic screening for genital herpes infection: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316(23):2525–2530.

- Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. 2007;370(9605):2127–2137.

- Agyemang E, Le QA, Warren T, et al. Performance of commercial enzyme-linked immunoassays 1 (EIA) for diagnosis of herpes simplex virus-1 and herpes simplex virus-2 infection in a clinical setting. Sex Transm Dis. 2017; doi:10.1097/olq.0000000000000689.

- Wald A, Zeh J, Selke S, et al. Reactivation of genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in asymptomatic seropositive persons. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(12):844–850.

- Gupta R, Wald A, Krantz E, et al. Valacyclovir and acyclovir for suppression of shedding of herpes simplex virus in the genital tract. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(8):1374–1381.

- Reitano M, Tyring S, Lang W, et al. Valaciclovir for the suppression of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection: a large-scale dose range-finding study. International Valaciclovir HSV Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(3): 603–610.

- Wald A, Selke S, Warren T, et al. Comparative efficacy of famciclovir and valacyclovir for suppression of recurrent genital herpes and viral shedding. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(9):529–533.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015 [published correction appears in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(33):924]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1–137.

- Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1376–1385.

- Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, Selke S, Zeh J, Corey L. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA. 2003;289(2):203–209.

- Healy SA, Mohan KM, Melvin AJ, Wald A. Primary maternal herpes simplex virus-1 gingivostomatitis during pregnancy and neonatal herpes: case series and literature review. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2012;1(4):299–305.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecoloigsts Committee on Practice Bulletins. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 82: Management of herpes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(6):1489–1498.

- Hollier LM, Wendel GD. Third trimester antiviral prophylaxis for preventing maternal genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) recurrences and neonatal infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(1):CD004946.

- Pinninti SG, Angara R, Feja KN, et al. Neonatal herpes disease following maternal antenatal antiviral suppressive therapy: a multicenter case series. J Pediatr. 2012;161(1):134–138.e1–e3.

- Vontver LA, Hickok DE, Brown Z, Reid L, Corey L. Recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection in pregnancy: infant outcome and frequency of asymptomatic recurrences. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1982;143(1):75–84.

- Fanfair RN, Zaidi A, Taylor LD, Xu F, Gottlieb S, Markowitz L. Trends in seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 among non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites aged 14 to 49 years–United States, 1988 to 2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(11):860–864.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, McQuillan GM. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2–United States, 1999-2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(3):325–333.

- Bernstein DI, Bellamy AR, Hook EW, 3rd, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(3):344–351.

- Kimberlin DW, Rouse DJ. Clinical practice. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(19):1970–1977.

- Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, Holmes KK. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98(6):958–972.

- Wald A, Zeh J, Selke S, Ashley RL, Corey L. Virologic characteristics of subclinical and symptomatic genital herpes infections. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(12):770–775.

- Reeves WC, Corey L, Adams HG, Vontver LA, Holmes KK. Risk of recurrence after first episodes of genital herpes. Relation to HSV type and antibody response. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(6):315–319.

- Phipps W, Saracino M, Magaret A, et al. Persistent genital herpes simplex virus-2 shedding years following the first clinical episode. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(2):180–187.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1–137.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al; US Preventive Task Force. Serologic screening for genital herpes infection: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316(23):2525–2530.

- Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. 2007;370(9605):2127–2137.

- Agyemang E, Le QA, Warren T, et al. Performance of commercial enzyme-linked immunoassays 1 (EIA) for diagnosis of herpes simplex virus-1 and herpes simplex virus-2 infection in a clinical setting. Sex Transm Dis. 2017; doi:10.1097/olq.0000000000000689.

- Wald A, Zeh J, Selke S, et al. Reactivation of genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in asymptomatic seropositive persons. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(12):844–850.

- Gupta R, Wald A, Krantz E, et al. Valacyclovir and acyclovir for suppression of shedding of herpes simplex virus in the genital tract. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(8):1374–1381.

- Reitano M, Tyring S, Lang W, et al. Valaciclovir for the suppression of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection: a large-scale dose range-finding study. International Valaciclovir HSV Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(3): 603–610.

- Wald A, Selke S, Warren T, et al. Comparative efficacy of famciclovir and valacyclovir for suppression of recurrent genital herpes and viral shedding. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(9):529–533.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015 [published correction appears in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(33):924]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1–137.

- Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1376–1385.

- Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, Selke S, Zeh J, Corey L. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA. 2003;289(2):203–209.

- Healy SA, Mohan KM, Melvin AJ, Wald A. Primary maternal herpes simplex virus-1 gingivostomatitis during pregnancy and neonatal herpes: case series and literature review. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2012;1(4):299–305.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecoloigsts Committee on Practice Bulletins. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 82: Management of herpes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(6):1489–1498.

- Hollier LM, Wendel GD. Third trimester antiviral prophylaxis for preventing maternal genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) recurrences and neonatal infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(1):CD004946.

- Pinninti SG, Angara R, Feja KN, et al. Neonatal herpes disease following maternal antenatal antiviral suppressive therapy: a multicenter case series. J Pediatr. 2012;161(1):134–138.e1–e3.

- Vontver LA, Hickok DE, Brown Z, Reid L, Corey L. Recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection in pregnancy: infant outcome and frequency of asymptomatic recurrences. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1982;143(1):75–84.