User login

During the course of my residency training, I have experienced and witnessed patients and visitors harassing health care workers (HCWs) by cursing or directing racial slurs at them, making sexist comments, or threatening their lives. What should be the correct response to this harassment? To say nothing may avoid conflict, but the silence perpetuates such abuse. To speak up may provoke aggression or even a physical assault. Further, does our response change if it is not the patient but someone who is accompanying them who exhibits this behavior?

I conducted a survey of psychiatry HCWs at our institution to evaluate the prevalence of and factors associated with such harassment.

An all-too-common problem

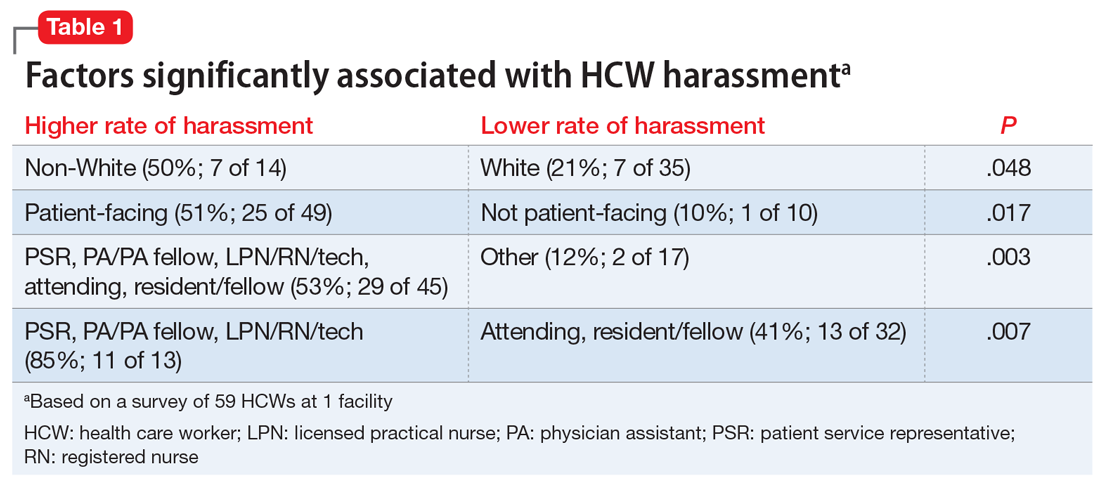

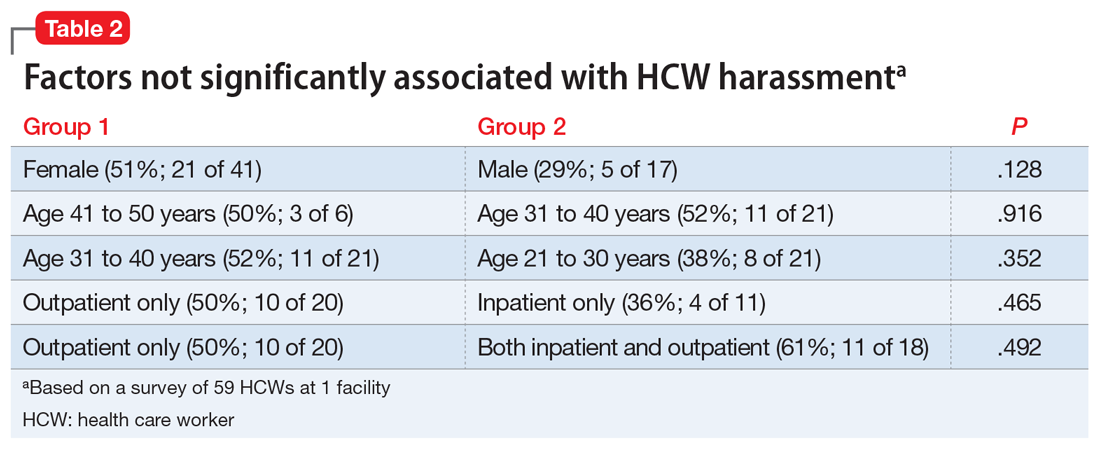

In a December 2020 internal survey at the University of Missouri Department of Psychiatry, 59 of 158 HCWs responded, and 26 (44%) reported experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse. Factors that were statistically significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included being non-White, working in a patient-facing position, and being a nonphysician patient-facing HCW (Table 1). Factors that were not significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included clinical setting, HCW age, and HCW gender (Table 2).

In addition to comments from patients and visitors, respondents stated that the harassment or abuse also included:

- physically threatening behavior and assault

- reporting a HCW for HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) violations after the HCW declined to provide an early refill of a controlled substance

- being accused of being a bad person for declining to prescribe a specific medication

- insults about not being intelligent enough to be on the treatment team

- comments from colleagues.

At the most basic level of response, the emergency department (ED) remains under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) obligation to see, screen, and stabilize any patient, and if psychiatry is consulted in the ED, we should similarly provide this standard of care. Beyond this, we can create behavioral plans for when a relevant diagnosis exists or does not exist, and patients and/or visitors can be terminated from their stay at the location/service/health care system. Whether or not a patient is receiving psychiatric care and/or treatment is irrelevant to the responses to harassment we might consider.

During the incident itself, we are empowered to remove ourselves from the patient encounter. Historically, HCWs have had strong opinions on the next steps, either deciding, “Yes, I am a professional and I will not be bullied,” or “No, I am a professional and I don’t need to deal with this.” Just as we prioritize our patients’ dignities, we should also respect our own and our colleagues’ dignities.

How harassment is handled at our facility

HCWs are commonly unsure whether to “call out” abusive comments during the encounter itself or afterwards. In our hospital, HCWs are encouraged to independently choose to immediately respond, immediately report to a supervisor or hospital security, or defer and report to leadership afterwards via the Patient Safety Network (PSN). The PSN is our hospital’s reporting system for medical errors, near misses, and abuse, neglect, and workplace violence. Relevant examples of abuse, neglect, and workplace violence include:

- Threats. Expression of intent to cause harm, including verbal or written threats and threatening body language

- Physical assault. Attacks ranging from slapping and beating to rape, the use of weapons, or homicide

- Sexual assault. Any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient, such as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape.

Continue to: Once complete...

Once complete, the PSN report is sent to Risk Management and other relevant groups, such as a 5-person team of security investigators, who are trained in trauma-informed interviewing and re-directive techniques. This team can immediately speak to the patient face-to-face in the inpatient setting or follow-up via phone in the outpatient setting.

The PSN report may result in the creation of a behavior plan for the patient that outlines the behaviors of concern, staff interventions, and consequences for persistent violations. The behavior plan is saved in the patient’s medical chart, and an alert pops up every time the chart is opened. The behavior plan is reviewed once annually for revision or deletion, as appropriate.

Lessons from our facility’s policy

In our health care system, our primary response to HCW harassment is to create a patient behavior plan that lays out specific expectations, care parameters, and consequences (up to terminating a patient from the entire health care system, except for EMTALA-level care). Clinicians are encouraged to report harassment to hospital administration, and a team of security investigators discusses expectations with the patient and/or visitors to prevent further abuse. We believe that describing our policies may be helpful to other health care systems and HCWs who confront this widespread issue.

During the course of my residency training, I have experienced and witnessed patients and visitors harassing health care workers (HCWs) by cursing or directing racial slurs at them, making sexist comments, or threatening their lives. What should be the correct response to this harassment? To say nothing may avoid conflict, but the silence perpetuates such abuse. To speak up may provoke aggression or even a physical assault. Further, does our response change if it is not the patient but someone who is accompanying them who exhibits this behavior?

I conducted a survey of psychiatry HCWs at our institution to evaluate the prevalence of and factors associated with such harassment.

An all-too-common problem

In a December 2020 internal survey at the University of Missouri Department of Psychiatry, 59 of 158 HCWs responded, and 26 (44%) reported experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse. Factors that were statistically significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included being non-White, working in a patient-facing position, and being a nonphysician patient-facing HCW (Table 1). Factors that were not significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included clinical setting, HCW age, and HCW gender (Table 2).

In addition to comments from patients and visitors, respondents stated that the harassment or abuse also included:

- physically threatening behavior and assault

- reporting a HCW for HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) violations after the HCW declined to provide an early refill of a controlled substance

- being accused of being a bad person for declining to prescribe a specific medication

- insults about not being intelligent enough to be on the treatment team

- comments from colleagues.

At the most basic level of response, the emergency department (ED) remains under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) obligation to see, screen, and stabilize any patient, and if psychiatry is consulted in the ED, we should similarly provide this standard of care. Beyond this, we can create behavioral plans for when a relevant diagnosis exists or does not exist, and patients and/or visitors can be terminated from their stay at the location/service/health care system. Whether or not a patient is receiving psychiatric care and/or treatment is irrelevant to the responses to harassment we might consider.

During the incident itself, we are empowered to remove ourselves from the patient encounter. Historically, HCWs have had strong opinions on the next steps, either deciding, “Yes, I am a professional and I will not be bullied,” or “No, I am a professional and I don’t need to deal with this.” Just as we prioritize our patients’ dignities, we should also respect our own and our colleagues’ dignities.

How harassment is handled at our facility

HCWs are commonly unsure whether to “call out” abusive comments during the encounter itself or afterwards. In our hospital, HCWs are encouraged to independently choose to immediately respond, immediately report to a supervisor or hospital security, or defer and report to leadership afterwards via the Patient Safety Network (PSN). The PSN is our hospital’s reporting system for medical errors, near misses, and abuse, neglect, and workplace violence. Relevant examples of abuse, neglect, and workplace violence include:

- Threats. Expression of intent to cause harm, including verbal or written threats and threatening body language

- Physical assault. Attacks ranging from slapping and beating to rape, the use of weapons, or homicide

- Sexual assault. Any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient, such as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape.

Continue to: Once complete...

Once complete, the PSN report is sent to Risk Management and other relevant groups, such as a 5-person team of security investigators, who are trained in trauma-informed interviewing and re-directive techniques. This team can immediately speak to the patient face-to-face in the inpatient setting or follow-up via phone in the outpatient setting.

The PSN report may result in the creation of a behavior plan for the patient that outlines the behaviors of concern, staff interventions, and consequences for persistent violations. The behavior plan is saved in the patient’s medical chart, and an alert pops up every time the chart is opened. The behavior plan is reviewed once annually for revision or deletion, as appropriate.

Lessons from our facility’s policy

In our health care system, our primary response to HCW harassment is to create a patient behavior plan that lays out specific expectations, care parameters, and consequences (up to terminating a patient from the entire health care system, except for EMTALA-level care). Clinicians are encouraged to report harassment to hospital administration, and a team of security investigators discusses expectations with the patient and/or visitors to prevent further abuse. We believe that describing our policies may be helpful to other health care systems and HCWs who confront this widespread issue.

During the course of my residency training, I have experienced and witnessed patients and visitors harassing health care workers (HCWs) by cursing or directing racial slurs at them, making sexist comments, or threatening their lives. What should be the correct response to this harassment? To say nothing may avoid conflict, but the silence perpetuates such abuse. To speak up may provoke aggression or even a physical assault. Further, does our response change if it is not the patient but someone who is accompanying them who exhibits this behavior?

I conducted a survey of psychiatry HCWs at our institution to evaluate the prevalence of and factors associated with such harassment.

An all-too-common problem

In a December 2020 internal survey at the University of Missouri Department of Psychiatry, 59 of 158 HCWs responded, and 26 (44%) reported experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse. Factors that were statistically significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included being non-White, working in a patient-facing position, and being a nonphysician patient-facing HCW (Table 1). Factors that were not significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included clinical setting, HCW age, and HCW gender (Table 2).

In addition to comments from patients and visitors, respondents stated that the harassment or abuse also included:

- physically threatening behavior and assault

- reporting a HCW for HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) violations after the HCW declined to provide an early refill of a controlled substance

- being accused of being a bad person for declining to prescribe a specific medication

- insults about not being intelligent enough to be on the treatment team

- comments from colleagues.

At the most basic level of response, the emergency department (ED) remains under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) obligation to see, screen, and stabilize any patient, and if psychiatry is consulted in the ED, we should similarly provide this standard of care. Beyond this, we can create behavioral plans for when a relevant diagnosis exists or does not exist, and patients and/or visitors can be terminated from their stay at the location/service/health care system. Whether or not a patient is receiving psychiatric care and/or treatment is irrelevant to the responses to harassment we might consider.

During the incident itself, we are empowered to remove ourselves from the patient encounter. Historically, HCWs have had strong opinions on the next steps, either deciding, “Yes, I am a professional and I will not be bullied,” or “No, I am a professional and I don’t need to deal with this.” Just as we prioritize our patients’ dignities, we should also respect our own and our colleagues’ dignities.

How harassment is handled at our facility

HCWs are commonly unsure whether to “call out” abusive comments during the encounter itself or afterwards. In our hospital, HCWs are encouraged to independently choose to immediately respond, immediately report to a supervisor or hospital security, or defer and report to leadership afterwards via the Patient Safety Network (PSN). The PSN is our hospital’s reporting system for medical errors, near misses, and abuse, neglect, and workplace violence. Relevant examples of abuse, neglect, and workplace violence include:

- Threats. Expression of intent to cause harm, including verbal or written threats and threatening body language

- Physical assault. Attacks ranging from slapping and beating to rape, the use of weapons, or homicide

- Sexual assault. Any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient, such as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape.

Continue to: Once complete...

Once complete, the PSN report is sent to Risk Management and other relevant groups, such as a 5-person team of security investigators, who are trained in trauma-informed interviewing and re-directive techniques. This team can immediately speak to the patient face-to-face in the inpatient setting or follow-up via phone in the outpatient setting.

The PSN report may result in the creation of a behavior plan for the patient that outlines the behaviors of concern, staff interventions, and consequences for persistent violations. The behavior plan is saved in the patient’s medical chart, and an alert pops up every time the chart is opened. The behavior plan is reviewed once annually for revision or deletion, as appropriate.

Lessons from our facility’s policy

In our health care system, our primary response to HCW harassment is to create a patient behavior plan that lays out specific expectations, care parameters, and consequences (up to terminating a patient from the entire health care system, except for EMTALA-level care). Clinicians are encouraged to report harassment to hospital administration, and a team of security investigators discusses expectations with the patient and/or visitors to prevent further abuse. We believe that describing our policies may be helpful to other health care systems and HCWs who confront this widespread issue.