User login

The online rating business is proliferating in the medical industry. This should really come as no surprise as health care is a service industry and online ratings have long been a staple in most other service industries. It has become routine practice for most of us to search such online reviews when seeking a pair of shoes, a toaster, or a restaurant; we almost can’t help but scour these sites to help us make the best decision possible.

Not dissimilarly, patients these days seek care and make decisions by using a variety of inputs, including:

- Anticipated cost (is the physician or practice in or out of network?).

- Availability or access to the service (location of the practice and how long it will take to be seen).

- How good the services and care will be when they get there.

That same article found that for those who used online physician ratings, about one-third had selected a physician based on good ratings, and about one-third had avoided a physician based on poor ratings. So patients do seem to be paying attention to these sites and seeking or avoiding care based on what information they find.

Based on that evidence, it is not surprising that so many physician rating sites have sprung up; not only is there a market demand for the availability of this information, the rating sites are also profitable for the host companies. Vitals.com, for example, makes most of its revenue from advertisements and turns a sizable profit every year. Other profitable health care rating sites include Healthgrades, Yelp, Zocdoc, and WebMD.

When I Google my own name, for example, Vitals.com is the first ratings website that appears in the search results. The first pop-up asks you to rate me and then it takes you to a site with all sorts of facts about me (most of which are notably inaccurate). If I had any online ratings (which I do not currently), you would then see my star ratings and any comments.

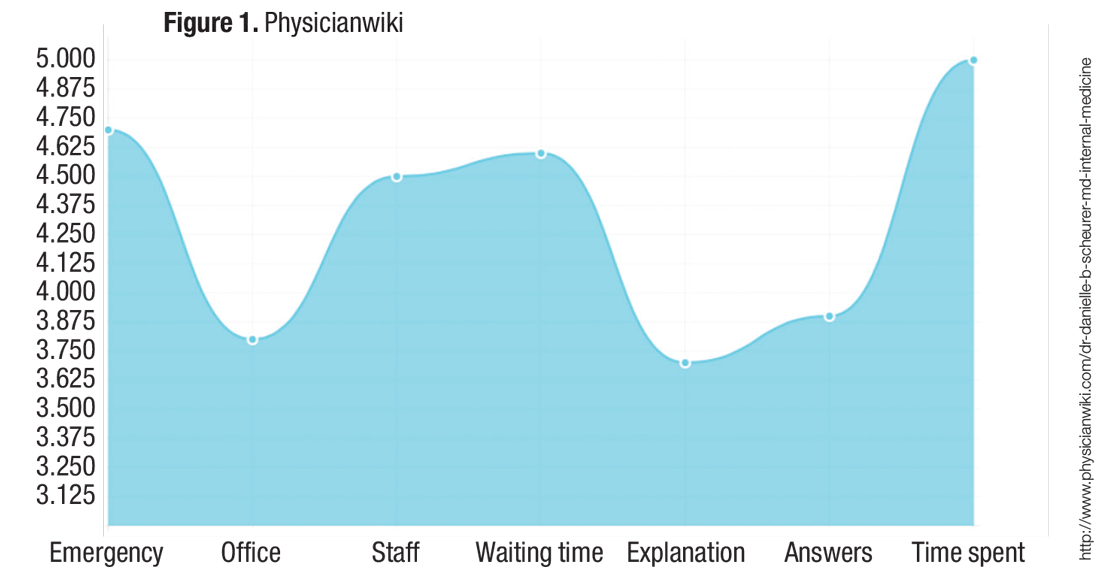

The second rating site that comes up for me via Google search is PhysicianWiki.com.There is a whole host of information on me (most of which is accurate), along with a set of personal ratings, including my office, my staff, and my waiting times (which, of course, do not make any sense given I am a hospitalist!). It is unclear how those ratings were generated or what volume of responses they represent.

My health care system proposed rolling out a similar online rating system, and it was met with great skepticism from many physicians. There were two primary concerns:

- They felt it was “tacky” and that the profession of medicine should not be relegated to oversimplified service ratings. They worried that they would feel pressured to please the patient rather than “do the right thing” for the patient. For example, they would be less likely to give difficult advice (such as lose weight or stop smoking) or to resist prescribing medications that they deemed unnecessary or frankly dangerous (for example, antibiotics or narcotics).

Although these are valid concerns, it is hard to ignore the proliferation and traffic of these online websites. For you and your team, I would recommend taking a look at what is online about the members of your group and thinking about online strategies to take control of the conversation.

I don’t think the controversy over online physician ratings will wane anytime soon, but there is no doubt that they are profitable for companies and are therefore highly likely to continue to multiply.

References

1.Hanauer DA, Zheng K, Singer DC, Gebremariam A, Davis MM. Public awareness, perception, and use of online physician rating sites. JAMA. 2014;311(7):734-735. 2. A to Z provider listing: find a U of U Health Care physician by last name. University of Utah website. Available at http://healthcare.utah.edu/fad. Accessed Nov. 16, 2016.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSc, SFHM, is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

The online rating business is proliferating in the medical industry. This should really come as no surprise as health care is a service industry and online ratings have long been a staple in most other service industries. It has become routine practice for most of us to search such online reviews when seeking a pair of shoes, a toaster, or a restaurant; we almost can’t help but scour these sites to help us make the best decision possible.

Not dissimilarly, patients these days seek care and make decisions by using a variety of inputs, including:

- Anticipated cost (is the physician or practice in or out of network?).

- Availability or access to the service (location of the practice and how long it will take to be seen).

- How good the services and care will be when they get there.

That same article found that for those who used online physician ratings, about one-third had selected a physician based on good ratings, and about one-third had avoided a physician based on poor ratings. So patients do seem to be paying attention to these sites and seeking or avoiding care based on what information they find.

Based on that evidence, it is not surprising that so many physician rating sites have sprung up; not only is there a market demand for the availability of this information, the rating sites are also profitable for the host companies. Vitals.com, for example, makes most of its revenue from advertisements and turns a sizable profit every year. Other profitable health care rating sites include Healthgrades, Yelp, Zocdoc, and WebMD.

When I Google my own name, for example, Vitals.com is the first ratings website that appears in the search results. The first pop-up asks you to rate me and then it takes you to a site with all sorts of facts about me (most of which are notably inaccurate). If I had any online ratings (which I do not currently), you would then see my star ratings and any comments.

The second rating site that comes up for me via Google search is PhysicianWiki.com.There is a whole host of information on me (most of which is accurate), along with a set of personal ratings, including my office, my staff, and my waiting times (which, of course, do not make any sense given I am a hospitalist!). It is unclear how those ratings were generated or what volume of responses they represent.

My health care system proposed rolling out a similar online rating system, and it was met with great skepticism from many physicians. There were two primary concerns:

- They felt it was “tacky” and that the profession of medicine should not be relegated to oversimplified service ratings. They worried that they would feel pressured to please the patient rather than “do the right thing” for the patient. For example, they would be less likely to give difficult advice (such as lose weight or stop smoking) or to resist prescribing medications that they deemed unnecessary or frankly dangerous (for example, antibiotics or narcotics).

Although these are valid concerns, it is hard to ignore the proliferation and traffic of these online websites. For you and your team, I would recommend taking a look at what is online about the members of your group and thinking about online strategies to take control of the conversation.

I don’t think the controversy over online physician ratings will wane anytime soon, but there is no doubt that they are profitable for companies and are therefore highly likely to continue to multiply.

References

1.Hanauer DA, Zheng K, Singer DC, Gebremariam A, Davis MM. Public awareness, perception, and use of online physician rating sites. JAMA. 2014;311(7):734-735. 2. A to Z provider listing: find a U of U Health Care physician by last name. University of Utah website. Available at http://healthcare.utah.edu/fad. Accessed Nov. 16, 2016.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSc, SFHM, is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

The online rating business is proliferating in the medical industry. This should really come as no surprise as health care is a service industry and online ratings have long been a staple in most other service industries. It has become routine practice for most of us to search such online reviews when seeking a pair of shoes, a toaster, or a restaurant; we almost can’t help but scour these sites to help us make the best decision possible.

Not dissimilarly, patients these days seek care and make decisions by using a variety of inputs, including:

- Anticipated cost (is the physician or practice in or out of network?).

- Availability or access to the service (location of the practice and how long it will take to be seen).

- How good the services and care will be when they get there.

That same article found that for those who used online physician ratings, about one-third had selected a physician based on good ratings, and about one-third had avoided a physician based on poor ratings. So patients do seem to be paying attention to these sites and seeking or avoiding care based on what information they find.

Based on that evidence, it is not surprising that so many physician rating sites have sprung up; not only is there a market demand for the availability of this information, the rating sites are also profitable for the host companies. Vitals.com, for example, makes most of its revenue from advertisements and turns a sizable profit every year. Other profitable health care rating sites include Healthgrades, Yelp, Zocdoc, and WebMD.

When I Google my own name, for example, Vitals.com is the first ratings website that appears in the search results. The first pop-up asks you to rate me and then it takes you to a site with all sorts of facts about me (most of which are notably inaccurate). If I had any online ratings (which I do not currently), you would then see my star ratings and any comments.

The second rating site that comes up for me via Google search is PhysicianWiki.com.There is a whole host of information on me (most of which is accurate), along with a set of personal ratings, including my office, my staff, and my waiting times (which, of course, do not make any sense given I am a hospitalist!). It is unclear how those ratings were generated or what volume of responses they represent.

My health care system proposed rolling out a similar online rating system, and it was met with great skepticism from many physicians. There were two primary concerns:

- They felt it was “tacky” and that the profession of medicine should not be relegated to oversimplified service ratings. They worried that they would feel pressured to please the patient rather than “do the right thing” for the patient. For example, they would be less likely to give difficult advice (such as lose weight or stop smoking) or to resist prescribing medications that they deemed unnecessary or frankly dangerous (for example, antibiotics or narcotics).

Although these are valid concerns, it is hard to ignore the proliferation and traffic of these online websites. For you and your team, I would recommend taking a look at what is online about the members of your group and thinking about online strategies to take control of the conversation.

I don’t think the controversy over online physician ratings will wane anytime soon, but there is no doubt that they are profitable for companies and are therefore highly likely to continue to multiply.

References

1.Hanauer DA, Zheng K, Singer DC, Gebremariam A, Davis MM. Public awareness, perception, and use of online physician rating sites. JAMA. 2014;311(7):734-735. 2. A to Z provider listing: find a U of U Health Care physician by last name. University of Utah website. Available at http://healthcare.utah.edu/fad. Accessed Nov. 16, 2016.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSc, SFHM, is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.