User login

More than 45% of people worldwide suffer from headache at some point in their life.1 Head pain can lead to disability and functional decline, yet headache disorders often are underdiagnosed and poorly assessed. For example, 60% of migraine and tension-type headaches go undiagnosed and 50% of persons suffering from migraine have severe functional disability or require bed rest.2-4

Because head pain can be associated with secondary medical and psychiatric conditions, diagnosis can be challenging. This article reviews the medical and psychological aspects of major headaches and assists with clinical assessment. We present clinical interviewing tools and a diagram to enhance focused, efficient assessment and inform treatment plans.

Classification of headache

Headache is a common complaint, yet it is often underdiagnosed and ineffectively treated. The World Health Organization estimates that, globally, 50% of people with headache self-treat their pain.5 The International Headache Society classifies headache as primary or secondary; approximately 90% of complaints are from primary headache.6

Assessment and diagnosis of headache can be complex because of overlapping, subjective symptoms. It is important to have a general understanding of primary and secondary causes of headache so that interrelated symptoms do not obscure the most accurate diagnosis and effective treatment course. Although most headache complaints are benign, ruling out secondary causes helps gauge the likelihood of developing severe sequelae from underlying pathology.

By definition, primary headaches are idiopathic and commonly include migraine, tension-type, cluster, and hemicrania continua headache. Secondary headaches have an underlying pathology, which could improve by targeting the disorder. Common secondary causes of headache include:

• trauma

• vascular abnormalities

• structural abnormalities

• chemical (including medications)

• inflammation or infection

• metabolic conditions

• diseases of the neck and pericranial and intracranial structures

• psychiatric conditions.

Table 1 illustrates common causes of head pain. More definitive criteria for symptoms and diagnosis can be found in the International Classification of Headache Disorders.7

Primary headache

Tension-type is the most common primary headache, accounting for more than one-half of all headaches.7 Patients usually describe a tight pain in a bilateral band-like distribution, which could be caused by sustained neck muscle contraction. Pain usually builds in intensity and can last 30 minutes to several days. There is a well-established association between emotional stress or depression and the development of tension-type headaches.8

Migraine typically causes pulsating pain in a localized area of the head that lasts as long as 72 hours and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phono-phobia, and aura. Patients report varying precipitating factors but commonly cite certain foods, menstruation, and sleep deprivation. Although rare, migraine with aura has been linked to ischemic stroke; most cases have been reported in female smokers and oral contraceptive users age <45.9

Because migraines can be debilitating, some patients—typically those with ≥4 attacks a month—opt for prophylactic medication. Effective prophylactics include amitriptyline, propranolol, divalproex sodium, and topiramate, which should be monitored closely and given a trial for several months before switching to another drug. Commonly used abortive treatments include triptans and anti-emetics such as metoclopramide.

Meperidine and ketorolac are popular second-line agents for migraine. Botulinum toxin A also has been used in severe cases to reduce the number of headache days in chronic migraine patients.6

Cluster headache is rare, but typically exhibits repeated burning and intense unilateral periorbital or retro-orbital pain that lasts 15 minutes to 3 hours over several weeks. Men are predominantly affected. Cluster headaches typically improve with oxygen treatment.

Biopsychosocial model of head pain

The biomedical model has helped iden tify pathophysiological pain mechanisms and pharmacotherapeutic agents for headache. However, during assessment, limiting one’s attention to the linear relationship between pathology, mechanism of action, and pain oversimplifies common questions clinicians face when assessing chronic head pain.

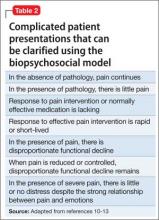

Advancements in the last 3 decades have expanded the conceptualization of head pain to integrate sociocultural, environmental, behavioral, affective, cognitive, and biological variables—otherwise known as the biopsychosocial model.10,11 The biopsychosocial model is a multidimensional theory that helps answer difficult clinical assessment questions and complex patient presentations (Table 2).10-13 Many unusual responses to pain treatment, questionable validity of pain behavior, and disproportionate pain perception and functional decline are explained by non-pathophysiological and non-biomechanical models.

Psychiatric comorbidity and head pain

Psychiatric conditions are highly prevalent among persons with primary headache. Verri et al14 found that 90% of chronic daily headache patients had ≥1 psychiatric condition; depression and anxiety were most common. Of concern, 1 study found that headache is associated with increased frequency of suicidal ideation among patients with chronic pain.15 It is critical for clinicians to screen for psychiatric comorbidities in patients with chronic headache. Conversely, clinicians might want to screen for headache in their patients with psychiatric illness.

Migraine. Mood disorders are common among patients who suffer from migraine. The rate of depression is 2 to 4 times higher in those with migraine compared with healthy controls.16,17 In a large-scale study, patients with migraine had a 1.9-fold higher risk (compared with controls) of having a comorbid depressive episode; a 2-fold higher risk of manic episodes; and a 3-fold higher risk of both mania and depression.18 In a study of 62 inpatients, Fasmer19 reported that 46% of patients with unipolar depression and 44% of patients with bipolar disorder experienced migraine (77% of the bipolar disorder patients with migraine had bipolar II disorder). Patients with migraine are at increased risk of suicide attempts (odds ratio 4.3; 95% CI, 1.2-15.7).20

Tension-type headache. The relationship between psychiatric comorbidity in tension-type headache is well established. In contrast to what is seen with migraines, Puca et al21 found a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders (52.5%) than depressive disorders (36.4%) in patients with tension-type headache. Generalized anxiety disorder was one of the most prevalent anxiety conditions (83.3%), and dysthymia was the most prevalent mood disorder (45.6%). In the same study, 21.7% of patients were found to have a comorbid somatoform disorder.21

Emotional and cognitive factors can co-occur in patients with tension-type headache and a comorbid psychiatric condition. For example, difficulty identifying or recognizing emotions—commonly referred to as alexithymia—has been linked to tension-type headache.22 Additionally, maladaptive cognitive appraisal of stress is more common among patients with tension-type headache when compared with those without headaches.23 Being mindful of and recognizing these co-occurring emotional and cognitive factors will help clinicians construct a more accurate assessment and effective behavioral treatment plan.

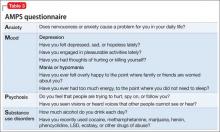

Clinical assessment with a useful mnemonic

Clinical assessment of psychiatric illness is essential when evaluating chronic pain patients. Using the acronym AMPS (Anxiety, Mood, Psychosis, and Substance use disorders) (Table 3) is an efficient way for the clinician to ask pertinent questions regarding common psychiatric conditions that could have a direct effect on chronic pain.24 Head pain can be more intense when combined with untreated anxiety, depression, psychosis, or a substance use disorder. Untreated anxiety, for example, can amplify sympathetic response to pain and complicate treatment.

Investigating head pain patients for an underlying mood disorder is essential to providing successful treatment. Consider:

• starting psychotherapy modalities that address both pain and psychiatric illness, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

• reframing unhelpful pain beliefs

• managing activity-rest levels

• biofeedback

• supportive group therapy

• reducing family members’ reinforcement of the patient’s pain behavior or sick role.25

Assessing for somatic symptom disorders

In addition to using the AMPS approach for psychiatric assessment, clinicians should evaluate for somatization, which can present as head pain. Somatic symptom disorders (SSD) are a class of conditions that are impacted by affective, cognitive, and reinforcing factors that might or might not be consciously or intentionally produced. Patients with an SSD have somatic symptoms that are distressing or cause significant disruption of daily life because of excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to the somatic symptoms, for ≥6 months. The Figure outlines SSD, related conditions, and their respective prominent symptoms to assist in the differential diagnosis.26

Note that some headache conditions present with severe distress because of their abrupt onset and severity of symptoms (eg, cluster headaches). Therefore, the expectation and likelihood of psychological disturbance should be factored into a diagnosis of SSD and related conditions as seen in the Figure.

Secondary factors of unusual pain behavior or treatment response. The role of thoughts, affect, and behaviors is clinically meaningful in understanding SSD and similar conditions. Specific questions about cultural beliefs and rituals as they relate to exacerbations of head pain are of value. Table 413,27 lists behavioral, cognitive, and affective dimensions of head pain using the biopsychosocial model, and further clarifies common questions that arise with unusual pain response and complex patient presentations, which were outlined in the beginning of the article.

Because depression and anxiety can be comorbid with head pain, it is important to recognize psychological factors that contribute to pain perception. Indifference or denial of emotional stress as a result of severe pain and disability can imply a somatization process, which could suggest emotional disconnection or dissociation from somatic functioning.28 This finding can be a component of alexithymia, in which a person is disconnected from emotions and how emotions impact the body. Therefore, recognizing alexithymia assists in identifying psychological factors when patients deny mood symptoms, particularly in tension-type headache.

Functional assessment to rule out the disproportional impact of pain on daily activities is helpful in understanding the somatization process. Neurocognitive functioning should be assessed, particularly because frontal and subcortical dysregulation has been observed in head pain sufferers.29,30 Patients with cognitive changes as a result of a medical illness (eg, stroke, head concussion, brain tumor, or seizures) are especially at risk for neurocognitive dysfunction.

Neuropsychological assessment can be useful, not only to assess neurocognitive functioning (eg, Repeated Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status) but to identify objective test profiles associated with altered motivation (eg, Rey 15-Item Test, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Form F Scale, Personality Assessment Inventory [PAI] Negative Impression Management) and somatization processes (eg, PAI Somatization Scale). These instruments help to identify the severity of psychiatric and neurocognitive symptoms by comparing scores to normative (eg, healthy control group), clinical (eg, somatization, traumatic brain injury, mild cognitive impairment), and altered motivation (eg, persons instructed to exaggerate symptoms) databases.

If the clinician pursues neurocognitive assessment, direct referral to a neuropsychologist, referral to neurologist, or administration of a cognitive screening tool such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Saint Louis University Mental Status, or Cognitive Log is recommended. If the cognitive screening is positive, next steps include: referring for full neuropsychological assessment, which includes complete cognitive and motor testing, personality testing, and integration of neuroimaging data (eg, MRI, CT scans, and/or EEG).

Assessing the patients’ self-talk or thought patterns as they describe their head pain will help clinicians understand belief systems that may be distorting the reality of the medical condition. For example, a patient might report that “my pain feels like someone is hitting me with an axe”; this is a catastrophic thought that can distort the clarity and perceptibility of pain. Encouraging patients to monitor and analyze their anxiety and associated negative thoughts is an important strategy for improving mood and decreasing somatization. Recording daily thoughts and CBT can help the patient identify and appropriately address his (her) cognitive distortions and futile thinking.

When implementing a treatment plan for somatization disorder, we propose the mnemonic device CARE MD:

• CBT

• Assess (by ruling out a medical cause for somatic complaints)

• Regular visits

• Empathy

• Med-psych interface (help the patient connect physical complaints and emotional stressors)

• Do no harm.

Clinical recommendations

Chronic head pain can be debilitating; psychodiagnostic assessment should therefore be considered an important part of the diagnosis and treatment plan. After ruling out common and emergent primary or secondary causes of head pain, consider psychiatric comorbidities. Depression and anxiety have a strong bidirectional relationship with chronic headache; therefore, we suggest evaluating patients with the intention of alleviating both psychiatric symptoms and head pain.

It is important to diligently assess for common psychiatric comorbidities; using the AMPS and CARE MD mnemonics, along with screening for somatization disorders, is an easy and effective way to evaluate for relevant psychiatric conditions associated with chronic head pain. Because many patients have unusual and complicated responses to head pain that can be explained by non-pathophysiological and non-biomechanical models, using the biopsychosocial model is essential for effective diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Abortive and prophylactic medical interventions, as well as behavioral, sociocultural, and cognitive assessment, are vital to a comprehensive treatment approach.

Bottom Line

The psychodiagnostic assessment can help the astute clinician identify comorbid psychiatric conditions, psychological factors, and somatic symptoms to develop a comprehensive biopsychosocial treatment plan for patients with chronic head pain. Rule out primary and secondary causes of pain and screen for somatization disorders. Consider medication and psychotherapeutic treatment options.

Related Resources

• Pompili M, Di Cosimo D, Innamorati M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic daily headache and migraine: a selective overview including personality traits and suicide risk. J Headache Pain. 2009;10(4):283-290.

• Sinclair AJ, Sturrock A, Davies B, et al. Headache management: pharmacological approaches [published online July 3, 2015]. Pract Neurol. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001167.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Meperidine • Demerol

Botulinum toxin A • Botox Metoclopramide • Reglan

Divalproex sodium • Depakote Propranolol • Inderide

Ketorolac • Toradol Topiramate • Topamax

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):193-210.

2. Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41(7):646-657.

3. The World Health Report 2001: Mental health: new understanding new hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

4. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_ disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf. Published 2004. Accessed July 31, 2015.

5. World Health Organization. Headache disorders. http:// www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs277/en/. Published October 2012. Accessed July 31, 2015.

6. Clinch C. Evaluation & management of headache. In: South- Paul JE, Matheny SC, Lewis EL. eds. Current diagnosis & treatment in family medicine, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015:293-297.

7. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629-808.

8. Mawet J, Kurth T, Ayata C. Migraine and stroke: in search of shared mechanisms. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(2):165-181.

9. Janke EA, Holroyd KA, Romanek K. Depression increases onset of tension-type headache following laboratory stress. Pain. 2004;111(3):230-238.

10. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136.

11. Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(5):535-544.

12. Turk DC, Flor H. Chronic pain: a biobehavioral perspective. In: Gatchel RJ, Turk DC, eds. Psychosocial factors in pain: critical perspectives. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999:18-34.

13. Andrasik F, Flor H, Turk DC. An expanded view of psychological aspects in head pain: the biopsychosocial model. Neurol Sci. 2005;26(suppl 2):s87-s91.

14. Verri AP, Proietti Cecchini A, Galli C, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in chronic daily headache. Cephalalgia. 1998; 18(suppl 21):45-49.

15. Ilgen MA, Zivin K, McCammon RJ, et al. Pain and suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(6):521-527.

16. Kowacs F, Socal MP, Ziomkowski SC, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety, and screening for mental disorders in migrainous patients. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(2):79-89.

17. Hamelsky SW, Lipton RB. Psychiatric comorbidity of migraine. Headache. 2006;46(9):1327-1333.

18. Nguyen TV, Low NC. Comorbidity of migraine and mood episodes in a nationally representative population-based sample. Headache. 2013;53(3):498-506.

19. Fasmer OB. The prevalence of migraine in patients with bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Cephalalgia. 2001; 21(9):894-899.

20. Breslau N. Migraine, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Neurology. 1992;42(2):392-395.

21. Puca F, Genco S, Prudenzano MP, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial stress in patients with tension-type headache from headache centers in Italy. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(3):159-164.

22. Yücel B, Kora K, Ozyalçín S, et al. Depression, automatic thoughts, alexithymia, and assertiveness in patients with tension-type headache. Headache. 2002;42(3):194-199.

23. Wittrock DA, Myers TC. The comparison of individuals with recurrent tension-type headache and headache-free controls in physiological response, appraisal, and coping with stressors: a review of the literature. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20(2):118-134.

24. Onate J, Xiong G, McCarron R. The primary care psychiatric interview. In: McCarron R, Xiong G, Bourgeois J. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2009:3-4.

25. Songer D. Psychotherapeutic approaches in the treatment of pain. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(5):19-24.

26. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

27. Hashmi JA, Baliki MN, Huang L, et al. Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain. 2013;136(pt 9):2751-2768.

28. Packard RC. Conversion headache. Headache. 1980;20(5):266-268.

29. Mongini F, Keller R, Deregibus A, et al. Frontal lobe dysfunction in patients with chronic migraine: a clinical-neuropsychological study. Psychiatry Res. 2005;133(1):101-106.

30. Martelli MF, Grayson RL, Zasler ND. Posttraumatic headache: neuropsychological and psychological effects and treatment implications. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1999;14(1):49-69.

More than 45% of people worldwide suffer from headache at some point in their life.1 Head pain can lead to disability and functional decline, yet headache disorders often are underdiagnosed and poorly assessed. For example, 60% of migraine and tension-type headaches go undiagnosed and 50% of persons suffering from migraine have severe functional disability or require bed rest.2-4

Because head pain can be associated with secondary medical and psychiatric conditions, diagnosis can be challenging. This article reviews the medical and psychological aspects of major headaches and assists with clinical assessment. We present clinical interviewing tools and a diagram to enhance focused, efficient assessment and inform treatment plans.

Classification of headache

Headache is a common complaint, yet it is often underdiagnosed and ineffectively treated. The World Health Organization estimates that, globally, 50% of people with headache self-treat their pain.5 The International Headache Society classifies headache as primary or secondary; approximately 90% of complaints are from primary headache.6

Assessment and diagnosis of headache can be complex because of overlapping, subjective symptoms. It is important to have a general understanding of primary and secondary causes of headache so that interrelated symptoms do not obscure the most accurate diagnosis and effective treatment course. Although most headache complaints are benign, ruling out secondary causes helps gauge the likelihood of developing severe sequelae from underlying pathology.

By definition, primary headaches are idiopathic and commonly include migraine, tension-type, cluster, and hemicrania continua headache. Secondary headaches have an underlying pathology, which could improve by targeting the disorder. Common secondary causes of headache include:

• trauma

• vascular abnormalities

• structural abnormalities

• chemical (including medications)

• inflammation or infection

• metabolic conditions

• diseases of the neck and pericranial and intracranial structures

• psychiatric conditions.

Table 1 illustrates common causes of head pain. More definitive criteria for symptoms and diagnosis can be found in the International Classification of Headache Disorders.7

Primary headache

Tension-type is the most common primary headache, accounting for more than one-half of all headaches.7 Patients usually describe a tight pain in a bilateral band-like distribution, which could be caused by sustained neck muscle contraction. Pain usually builds in intensity and can last 30 minutes to several days. There is a well-established association between emotional stress or depression and the development of tension-type headaches.8

Migraine typically causes pulsating pain in a localized area of the head that lasts as long as 72 hours and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phono-phobia, and aura. Patients report varying precipitating factors but commonly cite certain foods, menstruation, and sleep deprivation. Although rare, migraine with aura has been linked to ischemic stroke; most cases have been reported in female smokers and oral contraceptive users age <45.9

Because migraines can be debilitating, some patients—typically those with ≥4 attacks a month—opt for prophylactic medication. Effective prophylactics include amitriptyline, propranolol, divalproex sodium, and topiramate, which should be monitored closely and given a trial for several months before switching to another drug. Commonly used abortive treatments include triptans and anti-emetics such as metoclopramide.

Meperidine and ketorolac are popular second-line agents for migraine. Botulinum toxin A also has been used in severe cases to reduce the number of headache days in chronic migraine patients.6

Cluster headache is rare, but typically exhibits repeated burning and intense unilateral periorbital or retro-orbital pain that lasts 15 minutes to 3 hours over several weeks. Men are predominantly affected. Cluster headaches typically improve with oxygen treatment.

Biopsychosocial model of head pain

The biomedical model has helped iden tify pathophysiological pain mechanisms and pharmacotherapeutic agents for headache. However, during assessment, limiting one’s attention to the linear relationship between pathology, mechanism of action, and pain oversimplifies common questions clinicians face when assessing chronic head pain.

Advancements in the last 3 decades have expanded the conceptualization of head pain to integrate sociocultural, environmental, behavioral, affective, cognitive, and biological variables—otherwise known as the biopsychosocial model.10,11 The biopsychosocial model is a multidimensional theory that helps answer difficult clinical assessment questions and complex patient presentations (Table 2).10-13 Many unusual responses to pain treatment, questionable validity of pain behavior, and disproportionate pain perception and functional decline are explained by non-pathophysiological and non-biomechanical models.

Psychiatric comorbidity and head pain

Psychiatric conditions are highly prevalent among persons with primary headache. Verri et al14 found that 90% of chronic daily headache patients had ≥1 psychiatric condition; depression and anxiety were most common. Of concern, 1 study found that headache is associated with increased frequency of suicidal ideation among patients with chronic pain.15 It is critical for clinicians to screen for psychiatric comorbidities in patients with chronic headache. Conversely, clinicians might want to screen for headache in their patients with psychiatric illness.

Migraine. Mood disorders are common among patients who suffer from migraine. The rate of depression is 2 to 4 times higher in those with migraine compared with healthy controls.16,17 In a large-scale study, patients with migraine had a 1.9-fold higher risk (compared with controls) of having a comorbid depressive episode; a 2-fold higher risk of manic episodes; and a 3-fold higher risk of both mania and depression.18 In a study of 62 inpatients, Fasmer19 reported that 46% of patients with unipolar depression and 44% of patients with bipolar disorder experienced migraine (77% of the bipolar disorder patients with migraine had bipolar II disorder). Patients with migraine are at increased risk of suicide attempts (odds ratio 4.3; 95% CI, 1.2-15.7).20

Tension-type headache. The relationship between psychiatric comorbidity in tension-type headache is well established. In contrast to what is seen with migraines, Puca et al21 found a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders (52.5%) than depressive disorders (36.4%) in patients with tension-type headache. Generalized anxiety disorder was one of the most prevalent anxiety conditions (83.3%), and dysthymia was the most prevalent mood disorder (45.6%). In the same study, 21.7% of patients were found to have a comorbid somatoform disorder.21

Emotional and cognitive factors can co-occur in patients with tension-type headache and a comorbid psychiatric condition. For example, difficulty identifying or recognizing emotions—commonly referred to as alexithymia—has been linked to tension-type headache.22 Additionally, maladaptive cognitive appraisal of stress is more common among patients with tension-type headache when compared with those without headaches.23 Being mindful of and recognizing these co-occurring emotional and cognitive factors will help clinicians construct a more accurate assessment and effective behavioral treatment plan.

Clinical assessment with a useful mnemonic

Clinical assessment of psychiatric illness is essential when evaluating chronic pain patients. Using the acronym AMPS (Anxiety, Mood, Psychosis, and Substance use disorders) (Table 3) is an efficient way for the clinician to ask pertinent questions regarding common psychiatric conditions that could have a direct effect on chronic pain.24 Head pain can be more intense when combined with untreated anxiety, depression, psychosis, or a substance use disorder. Untreated anxiety, for example, can amplify sympathetic response to pain and complicate treatment.

Investigating head pain patients for an underlying mood disorder is essential to providing successful treatment. Consider:

• starting psychotherapy modalities that address both pain and psychiatric illness, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

• reframing unhelpful pain beliefs

• managing activity-rest levels

• biofeedback

• supportive group therapy

• reducing family members’ reinforcement of the patient’s pain behavior or sick role.25

Assessing for somatic symptom disorders

In addition to using the AMPS approach for psychiatric assessment, clinicians should evaluate for somatization, which can present as head pain. Somatic symptom disorders (SSD) are a class of conditions that are impacted by affective, cognitive, and reinforcing factors that might or might not be consciously or intentionally produced. Patients with an SSD have somatic symptoms that are distressing or cause significant disruption of daily life because of excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to the somatic symptoms, for ≥6 months. The Figure outlines SSD, related conditions, and their respective prominent symptoms to assist in the differential diagnosis.26

Note that some headache conditions present with severe distress because of their abrupt onset and severity of symptoms (eg, cluster headaches). Therefore, the expectation and likelihood of psychological disturbance should be factored into a diagnosis of SSD and related conditions as seen in the Figure.

Secondary factors of unusual pain behavior or treatment response. The role of thoughts, affect, and behaviors is clinically meaningful in understanding SSD and similar conditions. Specific questions about cultural beliefs and rituals as they relate to exacerbations of head pain are of value. Table 413,27 lists behavioral, cognitive, and affective dimensions of head pain using the biopsychosocial model, and further clarifies common questions that arise with unusual pain response and complex patient presentations, which were outlined in the beginning of the article.

Because depression and anxiety can be comorbid with head pain, it is important to recognize psychological factors that contribute to pain perception. Indifference or denial of emotional stress as a result of severe pain and disability can imply a somatization process, which could suggest emotional disconnection or dissociation from somatic functioning.28 This finding can be a component of alexithymia, in which a person is disconnected from emotions and how emotions impact the body. Therefore, recognizing alexithymia assists in identifying psychological factors when patients deny mood symptoms, particularly in tension-type headache.

Functional assessment to rule out the disproportional impact of pain on daily activities is helpful in understanding the somatization process. Neurocognitive functioning should be assessed, particularly because frontal and subcortical dysregulation has been observed in head pain sufferers.29,30 Patients with cognitive changes as a result of a medical illness (eg, stroke, head concussion, brain tumor, or seizures) are especially at risk for neurocognitive dysfunction.

Neuropsychological assessment can be useful, not only to assess neurocognitive functioning (eg, Repeated Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status) but to identify objective test profiles associated with altered motivation (eg, Rey 15-Item Test, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Form F Scale, Personality Assessment Inventory [PAI] Negative Impression Management) and somatization processes (eg, PAI Somatization Scale). These instruments help to identify the severity of psychiatric and neurocognitive symptoms by comparing scores to normative (eg, healthy control group), clinical (eg, somatization, traumatic brain injury, mild cognitive impairment), and altered motivation (eg, persons instructed to exaggerate symptoms) databases.

If the clinician pursues neurocognitive assessment, direct referral to a neuropsychologist, referral to neurologist, or administration of a cognitive screening tool such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Saint Louis University Mental Status, or Cognitive Log is recommended. If the cognitive screening is positive, next steps include: referring for full neuropsychological assessment, which includes complete cognitive and motor testing, personality testing, and integration of neuroimaging data (eg, MRI, CT scans, and/or EEG).

Assessing the patients’ self-talk or thought patterns as they describe their head pain will help clinicians understand belief systems that may be distorting the reality of the medical condition. For example, a patient might report that “my pain feels like someone is hitting me with an axe”; this is a catastrophic thought that can distort the clarity and perceptibility of pain. Encouraging patients to monitor and analyze their anxiety and associated negative thoughts is an important strategy for improving mood and decreasing somatization. Recording daily thoughts and CBT can help the patient identify and appropriately address his (her) cognitive distortions and futile thinking.

When implementing a treatment plan for somatization disorder, we propose the mnemonic device CARE MD:

• CBT

• Assess (by ruling out a medical cause for somatic complaints)

• Regular visits

• Empathy

• Med-psych interface (help the patient connect physical complaints and emotional stressors)

• Do no harm.

Clinical recommendations

Chronic head pain can be debilitating; psychodiagnostic assessment should therefore be considered an important part of the diagnosis and treatment plan. After ruling out common and emergent primary or secondary causes of head pain, consider psychiatric comorbidities. Depression and anxiety have a strong bidirectional relationship with chronic headache; therefore, we suggest evaluating patients with the intention of alleviating both psychiatric symptoms and head pain.

It is important to diligently assess for common psychiatric comorbidities; using the AMPS and CARE MD mnemonics, along with screening for somatization disorders, is an easy and effective way to evaluate for relevant psychiatric conditions associated with chronic head pain. Because many patients have unusual and complicated responses to head pain that can be explained by non-pathophysiological and non-biomechanical models, using the biopsychosocial model is essential for effective diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Abortive and prophylactic medical interventions, as well as behavioral, sociocultural, and cognitive assessment, are vital to a comprehensive treatment approach.

Bottom Line

The psychodiagnostic assessment can help the astute clinician identify comorbid psychiatric conditions, psychological factors, and somatic symptoms to develop a comprehensive biopsychosocial treatment plan for patients with chronic head pain. Rule out primary and secondary causes of pain and screen for somatization disorders. Consider medication and psychotherapeutic treatment options.

Related Resources

• Pompili M, Di Cosimo D, Innamorati M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic daily headache and migraine: a selective overview including personality traits and suicide risk. J Headache Pain. 2009;10(4):283-290.

• Sinclair AJ, Sturrock A, Davies B, et al. Headache management: pharmacological approaches [published online July 3, 2015]. Pract Neurol. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001167.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Meperidine • Demerol

Botulinum toxin A • Botox Metoclopramide • Reglan

Divalproex sodium • Depakote Propranolol • Inderide

Ketorolac • Toradol Topiramate • Topamax

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

More than 45% of people worldwide suffer from headache at some point in their life.1 Head pain can lead to disability and functional decline, yet headache disorders often are underdiagnosed and poorly assessed. For example, 60% of migraine and tension-type headaches go undiagnosed and 50% of persons suffering from migraine have severe functional disability or require bed rest.2-4

Because head pain can be associated with secondary medical and psychiatric conditions, diagnosis can be challenging. This article reviews the medical and psychological aspects of major headaches and assists with clinical assessment. We present clinical interviewing tools and a diagram to enhance focused, efficient assessment and inform treatment plans.

Classification of headache

Headache is a common complaint, yet it is often underdiagnosed and ineffectively treated. The World Health Organization estimates that, globally, 50% of people with headache self-treat their pain.5 The International Headache Society classifies headache as primary or secondary; approximately 90% of complaints are from primary headache.6

Assessment and diagnosis of headache can be complex because of overlapping, subjective symptoms. It is important to have a general understanding of primary and secondary causes of headache so that interrelated symptoms do not obscure the most accurate diagnosis and effective treatment course. Although most headache complaints are benign, ruling out secondary causes helps gauge the likelihood of developing severe sequelae from underlying pathology.

By definition, primary headaches are idiopathic and commonly include migraine, tension-type, cluster, and hemicrania continua headache. Secondary headaches have an underlying pathology, which could improve by targeting the disorder. Common secondary causes of headache include:

• trauma

• vascular abnormalities

• structural abnormalities

• chemical (including medications)

• inflammation or infection

• metabolic conditions

• diseases of the neck and pericranial and intracranial structures

• psychiatric conditions.

Table 1 illustrates common causes of head pain. More definitive criteria for symptoms and diagnosis can be found in the International Classification of Headache Disorders.7

Primary headache

Tension-type is the most common primary headache, accounting for more than one-half of all headaches.7 Patients usually describe a tight pain in a bilateral band-like distribution, which could be caused by sustained neck muscle contraction. Pain usually builds in intensity and can last 30 minutes to several days. There is a well-established association between emotional stress or depression and the development of tension-type headaches.8

Migraine typically causes pulsating pain in a localized area of the head that lasts as long as 72 hours and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phono-phobia, and aura. Patients report varying precipitating factors but commonly cite certain foods, menstruation, and sleep deprivation. Although rare, migraine with aura has been linked to ischemic stroke; most cases have been reported in female smokers and oral contraceptive users age <45.9

Because migraines can be debilitating, some patients—typically those with ≥4 attacks a month—opt for prophylactic medication. Effective prophylactics include amitriptyline, propranolol, divalproex sodium, and topiramate, which should be monitored closely and given a trial for several months before switching to another drug. Commonly used abortive treatments include triptans and anti-emetics such as metoclopramide.

Meperidine and ketorolac are popular second-line agents for migraine. Botulinum toxin A also has been used in severe cases to reduce the number of headache days in chronic migraine patients.6

Cluster headache is rare, but typically exhibits repeated burning and intense unilateral periorbital or retro-orbital pain that lasts 15 minutes to 3 hours over several weeks. Men are predominantly affected. Cluster headaches typically improve with oxygen treatment.

Biopsychosocial model of head pain

The biomedical model has helped iden tify pathophysiological pain mechanisms and pharmacotherapeutic agents for headache. However, during assessment, limiting one’s attention to the linear relationship between pathology, mechanism of action, and pain oversimplifies common questions clinicians face when assessing chronic head pain.

Advancements in the last 3 decades have expanded the conceptualization of head pain to integrate sociocultural, environmental, behavioral, affective, cognitive, and biological variables—otherwise known as the biopsychosocial model.10,11 The biopsychosocial model is a multidimensional theory that helps answer difficult clinical assessment questions and complex patient presentations (Table 2).10-13 Many unusual responses to pain treatment, questionable validity of pain behavior, and disproportionate pain perception and functional decline are explained by non-pathophysiological and non-biomechanical models.

Psychiatric comorbidity and head pain

Psychiatric conditions are highly prevalent among persons with primary headache. Verri et al14 found that 90% of chronic daily headache patients had ≥1 psychiatric condition; depression and anxiety were most common. Of concern, 1 study found that headache is associated with increased frequency of suicidal ideation among patients with chronic pain.15 It is critical for clinicians to screen for psychiatric comorbidities in patients with chronic headache. Conversely, clinicians might want to screen for headache in their patients with psychiatric illness.

Migraine. Mood disorders are common among patients who suffer from migraine. The rate of depression is 2 to 4 times higher in those with migraine compared with healthy controls.16,17 In a large-scale study, patients with migraine had a 1.9-fold higher risk (compared with controls) of having a comorbid depressive episode; a 2-fold higher risk of manic episodes; and a 3-fold higher risk of both mania and depression.18 In a study of 62 inpatients, Fasmer19 reported that 46% of patients with unipolar depression and 44% of patients with bipolar disorder experienced migraine (77% of the bipolar disorder patients with migraine had bipolar II disorder). Patients with migraine are at increased risk of suicide attempts (odds ratio 4.3; 95% CI, 1.2-15.7).20

Tension-type headache. The relationship between psychiatric comorbidity in tension-type headache is well established. In contrast to what is seen with migraines, Puca et al21 found a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders (52.5%) than depressive disorders (36.4%) in patients with tension-type headache. Generalized anxiety disorder was one of the most prevalent anxiety conditions (83.3%), and dysthymia was the most prevalent mood disorder (45.6%). In the same study, 21.7% of patients were found to have a comorbid somatoform disorder.21

Emotional and cognitive factors can co-occur in patients with tension-type headache and a comorbid psychiatric condition. For example, difficulty identifying or recognizing emotions—commonly referred to as alexithymia—has been linked to tension-type headache.22 Additionally, maladaptive cognitive appraisal of stress is more common among patients with tension-type headache when compared with those without headaches.23 Being mindful of and recognizing these co-occurring emotional and cognitive factors will help clinicians construct a more accurate assessment and effective behavioral treatment plan.

Clinical assessment with a useful mnemonic

Clinical assessment of psychiatric illness is essential when evaluating chronic pain patients. Using the acronym AMPS (Anxiety, Mood, Psychosis, and Substance use disorders) (Table 3) is an efficient way for the clinician to ask pertinent questions regarding common psychiatric conditions that could have a direct effect on chronic pain.24 Head pain can be more intense when combined with untreated anxiety, depression, psychosis, or a substance use disorder. Untreated anxiety, for example, can amplify sympathetic response to pain and complicate treatment.

Investigating head pain patients for an underlying mood disorder is essential to providing successful treatment. Consider:

• starting psychotherapy modalities that address both pain and psychiatric illness, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

• reframing unhelpful pain beliefs

• managing activity-rest levels

• biofeedback

• supportive group therapy

• reducing family members’ reinforcement of the patient’s pain behavior or sick role.25

Assessing for somatic symptom disorders

In addition to using the AMPS approach for psychiatric assessment, clinicians should evaluate for somatization, which can present as head pain. Somatic symptom disorders (SSD) are a class of conditions that are impacted by affective, cognitive, and reinforcing factors that might or might not be consciously or intentionally produced. Patients with an SSD have somatic symptoms that are distressing or cause significant disruption of daily life because of excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to the somatic symptoms, for ≥6 months. The Figure outlines SSD, related conditions, and their respective prominent symptoms to assist in the differential diagnosis.26

Note that some headache conditions present with severe distress because of their abrupt onset and severity of symptoms (eg, cluster headaches). Therefore, the expectation and likelihood of psychological disturbance should be factored into a diagnosis of SSD and related conditions as seen in the Figure.

Secondary factors of unusual pain behavior or treatment response. The role of thoughts, affect, and behaviors is clinically meaningful in understanding SSD and similar conditions. Specific questions about cultural beliefs and rituals as they relate to exacerbations of head pain are of value. Table 413,27 lists behavioral, cognitive, and affective dimensions of head pain using the biopsychosocial model, and further clarifies common questions that arise with unusual pain response and complex patient presentations, which were outlined in the beginning of the article.

Because depression and anxiety can be comorbid with head pain, it is important to recognize psychological factors that contribute to pain perception. Indifference or denial of emotional stress as a result of severe pain and disability can imply a somatization process, which could suggest emotional disconnection or dissociation from somatic functioning.28 This finding can be a component of alexithymia, in which a person is disconnected from emotions and how emotions impact the body. Therefore, recognizing alexithymia assists in identifying psychological factors when patients deny mood symptoms, particularly in tension-type headache.

Functional assessment to rule out the disproportional impact of pain on daily activities is helpful in understanding the somatization process. Neurocognitive functioning should be assessed, particularly because frontal and subcortical dysregulation has been observed in head pain sufferers.29,30 Patients with cognitive changes as a result of a medical illness (eg, stroke, head concussion, brain tumor, or seizures) are especially at risk for neurocognitive dysfunction.

Neuropsychological assessment can be useful, not only to assess neurocognitive functioning (eg, Repeated Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status) but to identify objective test profiles associated with altered motivation (eg, Rey 15-Item Test, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Form F Scale, Personality Assessment Inventory [PAI] Negative Impression Management) and somatization processes (eg, PAI Somatization Scale). These instruments help to identify the severity of psychiatric and neurocognitive symptoms by comparing scores to normative (eg, healthy control group), clinical (eg, somatization, traumatic brain injury, mild cognitive impairment), and altered motivation (eg, persons instructed to exaggerate symptoms) databases.

If the clinician pursues neurocognitive assessment, direct referral to a neuropsychologist, referral to neurologist, or administration of a cognitive screening tool such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Saint Louis University Mental Status, or Cognitive Log is recommended. If the cognitive screening is positive, next steps include: referring for full neuropsychological assessment, which includes complete cognitive and motor testing, personality testing, and integration of neuroimaging data (eg, MRI, CT scans, and/or EEG).

Assessing the patients’ self-talk or thought patterns as they describe their head pain will help clinicians understand belief systems that may be distorting the reality of the medical condition. For example, a patient might report that “my pain feels like someone is hitting me with an axe”; this is a catastrophic thought that can distort the clarity and perceptibility of pain. Encouraging patients to monitor and analyze their anxiety and associated negative thoughts is an important strategy for improving mood and decreasing somatization. Recording daily thoughts and CBT can help the patient identify and appropriately address his (her) cognitive distortions and futile thinking.

When implementing a treatment plan for somatization disorder, we propose the mnemonic device CARE MD:

• CBT

• Assess (by ruling out a medical cause for somatic complaints)

• Regular visits

• Empathy

• Med-psych interface (help the patient connect physical complaints and emotional stressors)

• Do no harm.

Clinical recommendations

Chronic head pain can be debilitating; psychodiagnostic assessment should therefore be considered an important part of the diagnosis and treatment plan. After ruling out common and emergent primary or secondary causes of head pain, consider psychiatric comorbidities. Depression and anxiety have a strong bidirectional relationship with chronic headache; therefore, we suggest evaluating patients with the intention of alleviating both psychiatric symptoms and head pain.

It is important to diligently assess for common psychiatric comorbidities; using the AMPS and CARE MD mnemonics, along with screening for somatization disorders, is an easy and effective way to evaluate for relevant psychiatric conditions associated with chronic head pain. Because many patients have unusual and complicated responses to head pain that can be explained by non-pathophysiological and non-biomechanical models, using the biopsychosocial model is essential for effective diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Abortive and prophylactic medical interventions, as well as behavioral, sociocultural, and cognitive assessment, are vital to a comprehensive treatment approach.

Bottom Line

The psychodiagnostic assessment can help the astute clinician identify comorbid psychiatric conditions, psychological factors, and somatic symptoms to develop a comprehensive biopsychosocial treatment plan for patients with chronic head pain. Rule out primary and secondary causes of pain and screen for somatization disorders. Consider medication and psychotherapeutic treatment options.

Related Resources

• Pompili M, Di Cosimo D, Innamorati M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic daily headache and migraine: a selective overview including personality traits and suicide risk. J Headache Pain. 2009;10(4):283-290.

• Sinclair AJ, Sturrock A, Davies B, et al. Headache management: pharmacological approaches [published online July 3, 2015]. Pract Neurol. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001167.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Meperidine • Demerol

Botulinum toxin A • Botox Metoclopramide • Reglan

Divalproex sodium • Depakote Propranolol • Inderide

Ketorolac • Toradol Topiramate • Topamax

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):193-210.

2. Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41(7):646-657.

3. The World Health Report 2001: Mental health: new understanding new hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

4. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_ disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf. Published 2004. Accessed July 31, 2015.

5. World Health Organization. Headache disorders. http:// www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs277/en/. Published October 2012. Accessed July 31, 2015.

6. Clinch C. Evaluation & management of headache. In: South- Paul JE, Matheny SC, Lewis EL. eds. Current diagnosis & treatment in family medicine, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015:293-297.

7. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629-808.

8. Mawet J, Kurth T, Ayata C. Migraine and stroke: in search of shared mechanisms. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(2):165-181.

9. Janke EA, Holroyd KA, Romanek K. Depression increases onset of tension-type headache following laboratory stress. Pain. 2004;111(3):230-238.

10. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136.

11. Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(5):535-544.

12. Turk DC, Flor H. Chronic pain: a biobehavioral perspective. In: Gatchel RJ, Turk DC, eds. Psychosocial factors in pain: critical perspectives. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999:18-34.

13. Andrasik F, Flor H, Turk DC. An expanded view of psychological aspects in head pain: the biopsychosocial model. Neurol Sci. 2005;26(suppl 2):s87-s91.

14. Verri AP, Proietti Cecchini A, Galli C, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in chronic daily headache. Cephalalgia. 1998; 18(suppl 21):45-49.

15. Ilgen MA, Zivin K, McCammon RJ, et al. Pain and suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(6):521-527.

16. Kowacs F, Socal MP, Ziomkowski SC, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety, and screening for mental disorders in migrainous patients. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(2):79-89.

17. Hamelsky SW, Lipton RB. Psychiatric comorbidity of migraine. Headache. 2006;46(9):1327-1333.

18. Nguyen TV, Low NC. Comorbidity of migraine and mood episodes in a nationally representative population-based sample. Headache. 2013;53(3):498-506.

19. Fasmer OB. The prevalence of migraine in patients with bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Cephalalgia. 2001; 21(9):894-899.

20. Breslau N. Migraine, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Neurology. 1992;42(2):392-395.

21. Puca F, Genco S, Prudenzano MP, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial stress in patients with tension-type headache from headache centers in Italy. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(3):159-164.

22. Yücel B, Kora K, Ozyalçín S, et al. Depression, automatic thoughts, alexithymia, and assertiveness in patients with tension-type headache. Headache. 2002;42(3):194-199.

23. Wittrock DA, Myers TC. The comparison of individuals with recurrent tension-type headache and headache-free controls in physiological response, appraisal, and coping with stressors: a review of the literature. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20(2):118-134.

24. Onate J, Xiong G, McCarron R. The primary care psychiatric interview. In: McCarron R, Xiong G, Bourgeois J. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2009:3-4.

25. Songer D. Psychotherapeutic approaches in the treatment of pain. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(5):19-24.

26. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

27. Hashmi JA, Baliki MN, Huang L, et al. Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain. 2013;136(pt 9):2751-2768.

28. Packard RC. Conversion headache. Headache. 1980;20(5):266-268.

29. Mongini F, Keller R, Deregibus A, et al. Frontal lobe dysfunction in patients with chronic migraine: a clinical-neuropsychological study. Psychiatry Res. 2005;133(1):101-106.

30. Martelli MF, Grayson RL, Zasler ND. Posttraumatic headache: neuropsychological and psychological effects and treatment implications. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1999;14(1):49-69.

1. Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):193-210.

2. Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41(7):646-657.

3. The World Health Report 2001: Mental health: new understanding new hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

4. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_ disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf. Published 2004. Accessed July 31, 2015.

5. World Health Organization. Headache disorders. http:// www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs277/en/. Published October 2012. Accessed July 31, 2015.

6. Clinch C. Evaluation & management of headache. In: South- Paul JE, Matheny SC, Lewis EL. eds. Current diagnosis & treatment in family medicine, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015:293-297.

7. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629-808.

8. Mawet J, Kurth T, Ayata C. Migraine and stroke: in search of shared mechanisms. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(2):165-181.

9. Janke EA, Holroyd KA, Romanek K. Depression increases onset of tension-type headache following laboratory stress. Pain. 2004;111(3):230-238.

10. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136.

11. Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(5):535-544.

12. Turk DC, Flor H. Chronic pain: a biobehavioral perspective. In: Gatchel RJ, Turk DC, eds. Psychosocial factors in pain: critical perspectives. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999:18-34.

13. Andrasik F, Flor H, Turk DC. An expanded view of psychological aspects in head pain: the biopsychosocial model. Neurol Sci. 2005;26(suppl 2):s87-s91.

14. Verri AP, Proietti Cecchini A, Galli C, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in chronic daily headache. Cephalalgia. 1998; 18(suppl 21):45-49.

15. Ilgen MA, Zivin K, McCammon RJ, et al. Pain and suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(6):521-527.

16. Kowacs F, Socal MP, Ziomkowski SC, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety, and screening for mental disorders in migrainous patients. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(2):79-89.

17. Hamelsky SW, Lipton RB. Psychiatric comorbidity of migraine. Headache. 2006;46(9):1327-1333.

18. Nguyen TV, Low NC. Comorbidity of migraine and mood episodes in a nationally representative population-based sample. Headache. 2013;53(3):498-506.

19. Fasmer OB. The prevalence of migraine in patients with bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Cephalalgia. 2001; 21(9):894-899.

20. Breslau N. Migraine, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Neurology. 1992;42(2):392-395.

21. Puca F, Genco S, Prudenzano MP, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial stress in patients with tension-type headache from headache centers in Italy. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(3):159-164.

22. Yücel B, Kora K, Ozyalçín S, et al. Depression, automatic thoughts, alexithymia, and assertiveness in patients with tension-type headache. Headache. 2002;42(3):194-199.

23. Wittrock DA, Myers TC. The comparison of individuals with recurrent tension-type headache and headache-free controls in physiological response, appraisal, and coping with stressors: a review of the literature. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20(2):118-134.

24. Onate J, Xiong G, McCarron R. The primary care psychiatric interview. In: McCarron R, Xiong G, Bourgeois J. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2009:3-4.

25. Songer D. Psychotherapeutic approaches in the treatment of pain. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(5):19-24.

26. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

27. Hashmi JA, Baliki MN, Huang L, et al. Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain. 2013;136(pt 9):2751-2768.

28. Packard RC. Conversion headache. Headache. 1980;20(5):266-268.

29. Mongini F, Keller R, Deregibus A, et al. Frontal lobe dysfunction in patients with chronic migraine: a clinical-neuropsychological study. Psychiatry Res. 2005;133(1):101-106.

30. Martelli MF, Grayson RL, Zasler ND. Posttraumatic headache: neuropsychological and psychological effects and treatment implications. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1999;14(1):49-69.