User login

Chronic pain and psychiatric illness: Managing comorbid conditions

Pain is one of the most common symptoms for which patients seek medical care, with an associated estimated annual cost of $600 billion.1 Using a multimodal approach to care—thorough evaluation, cognitive-behavioral and psychophysiological therapy, physical therapy, medications, and other interventions—can help patients effectively manage their condition and achieve healthier outcomes.

Evaluating a patient with pain

When developing a safe, comprehensive, and effective treatment plan for patients with chronic pain, first perform a thorough history and physical exam using the following elements:

Pain history. The PQRST mnemonic (Table 1) can help you obtain critical information and assist in determining the appropriate diagnosis and cause of the patient’s pain complaints.

Psychiatric history. Document the mental health history of the patient and first-degree relatives.

Medical history. Knowing the medical history could reveal comorbidities contributing to a patient’s pain complaint.

Treatment history. Listing past and current treatments for pain, including effectiveness, helps the clinician understand if an existing treatment plan should be modified.

Functional status. Document current level of daily activity, how life activities are affected by pain; strategies used to help cope with pain; level of physical and emotional support provided in home, work, and school environments; and active stressors (eg, financial, interpersonal).

Psychosocial history. Document historical information related to coping skills, trauma history, family of origin, abuse, interpersonal relationships, social support, and academic and vocational functioning.

Substance use or abuse. Assess for use of controlled substances (ie, early refills; lost medications; obtaining medications from multiple prescribers, friends, families, or strangers; use of prescribed and non-prescribed medications for non-medical and medical purposes), nicotine, alcohol, illicit substances, and caffeine. A thorough inventory can help to identify substances a patient is using that could affect daily functioning and pain level.

Behavioral observations. Assessing mental status (eg, insight, pain behavior, cooperation) can be useful. Paying attention to pain behaviors, such as complaints of pain, decreased activity, increased medication intake, or altered facial expressions or body posture, can help the clinician gain insight to the extent that pain affects the patient’s quality of life.

The information gathered in the patient evaluation can be used to design a multimodal treatment plan to achieve maximum effectiveness.

Assessing psychiatric illness

Current approaches to pain evaluation and treatment recommend use of a biopsychosocial orientation because psychological, behavioral, and social factors can influence the experience and impact of pain, regardless of the primary cause.2 A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment plan should consider the broader context in which a patient’s pain occurs.

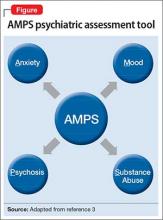

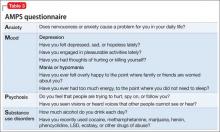

Regarding psychiatric illness, past and current symptoms, treatment history, and risk assessment should all be included. Using the “AMPS approach” (Figure)3—assessing Anxiety, Mood (depression and mania), Psychotic symptoms (paranoid ideation and hallucinations), and Substance use—helps screen for comorbid psychiatric conditions in patients with chronic pain.

Sleep assessment

Chronic pain patients often experience significant sleep disturbance that could be caused by physiological aspects of the pain condition, environmental factors (eg, uncomfortable bedding), a comorbid sleep disorder (eg, sleep apnea), a psychiatric disorder, or a combination of the above.

Obstructive and central sleep apnea are characterized by nighttime hypoxia, which leads to frequent disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and often manifests as daytime fatigue, irritability, depression, drowsiness, headaches, and increased pain sensitivity. Changes in sleep arousal can lead to neuropsychological changes during the day, such as decreased attention, memory problems, impaired executive functioning, and reduced impulse control.

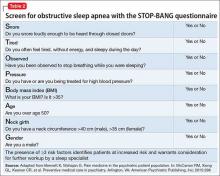

Screen patients for central and obstructive sleep apnea before prescribing opioids or benzodiazepines for pain because these medications can cause or exacerbate underlying sleep apnea. Although many screening tools, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, assess daytime somnolence,4 the STOP-BANG questionnaire is a quick, validated, and efficient screening tool that often is used to assess sleep apnea risk5,6 (Table 2). The presence of ≥3 risk factors identifies patients at increased risk and warrants consideration for further workup by a sleep specialist.7,8

Pharmacotherapy for chronic pain

Non-opioid medications. Pain can be broadly categorized as neuropathic or nociceptive. Neuropathic pain can be described by patients as numbness, burning, electric-like, and tingling, and is associated with nerve damage. Nociceptive pain commonly is described as similar to a toothache with descriptors such as stabbing, sharp, or a dull aching sensation; it is often, but not always, associated with acute injury or ongoing trauma to tissue. Drug treatment is most successful when the appropriate class of medication is matched to the specific type of pain.

Nociceptive pain often is successfully treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen. Non-selective COX inhibitors (eg, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac) and COX-2 selective inhibitors (eg, celecoxib) have been associated with cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and renal disease; acetaminophen is associated with liver dysfunction.9-11 However, the absolute risk for complications in healthy patients is low.12 To minimize risk, use these agents for the shortest duration and at the lowest effective dosage possible.

Neuropathic pain can be addressed with certain antidepressants13—specifically, those that increase serotonin and norepinephrine (eg, tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs] and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs]), or medications that block ion channels (eg, anticonvulsants). TCAs (eg, desipramine, nortriptyline, amitriptyline) are among the best studied and most cost effective medications for treating neuropathic pain,14,15 but they can have sedating and anticholinergic effects, as well as cardiac adverse effects (ie, prolongation of the QTc interval). SNRIs (eg, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran) can be effective and often are better tolerated than TCAs.14

Some newer anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin and pregabalin) have been found to be more effective than placebo for a variety of neuropathic pain conditions.16,17 Although they have few drug-drug interactions, anticonvulsants can cause dizziness, forgetfulness, and sedation. These adverse effects can be minimized by starting at a low dosage and titrating carefully. Because hepatic or renal impairment can affect metabolism or excretion of these drugs, review the prescribing information to determine safe dosing.

Targeted injection of medications to major pain generators (eg, an epidural steroid for radicular neck and back pain; facet injections for facet-related neck and back pain; trigger point injections for myofascial pain; occipital nerve blocks for occipital neuralgia; and botulinum toxin A injections for chronic migraine headache) can be effective in reducing discomfort and increasing function in patients with chronic pain. A detailed discussion of such therapies is beyond the scope of this article, but have been reviewed extensively elsewhere.18,19

Opioids. Although there is little evidence of long-term efficacy with chronic opioid therapy for most patients, a trial of opioids might be warranted for select patients who do not respond to other medications. Because the risk–benefit ratio for chronic opioid therapy is high,20-22 a decision to initiate a trial of a low-dosage opioid should be made only after careful consideration of those risks. It is generally agreed that treatment of chronic pain with low-dosage opioid therapy is more likely to be successful when it is used as an adjuvant to non-opioid modalities (eg, physical reconditioning, injection therapies, spinal cord stimulation, neurobehavioral interventions, non-opioid medications).

The Federation of State Medical Boards has stated that excessive reliance on opioid medications for treating chronic pain is a deviation from best practices.23 To maximize benefit and minimize risk, clinicians should carefully select appropriate patients, establish functional goals, and regularly monitor for efficacy and compliance. Thoroughly document these steps in the patient’s record for later reference.23

After establishing a clinical diagnosis for the cause of the pain, you should determine the risk of opioid abuse or misuse by using any one of the available risk assessment tools (Box). Understand, however, that no single tool has been shown to be more effective than others.

Although patients and some clinicians tend to overvalue the benefits of chronic opioid therapy, many do not fully appreciate the risks (eg, respiratory depression and death), which can be exacerbated if the patient is using other substance that suppress respiration (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, and illicit substances). Written informed consent and treatment agreement is highly recommended; components of such a document are listed in Table 3.23

Develop a treatment plan that emphasizes functional goals based on the patient’s physical limitations and that incorporates some type of daily, atraumatic physical activity. This plan should be documented and reviewed regularly to help monitor treatment effectiveness.

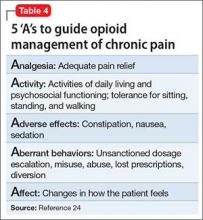

After an initial trial of a few weeks, the patient and clinician should meet to review the 5 “A”s (Table 4)24 to determine the success of the opioid regimen. Consulting your state’s prescription drug monitoring program (if one is available), obtaining a random urine drug test, and doing a pill count can provide useful, objective data. If the patient has not made progress but has experienced no adverse effects, then a small dosage increase might be warranted. If any of the 5 “A”s indicates lack of improvement or increased risk, consider stopping opioid therapy and exploring non-opioid options to manage chronic pain.

Referrals to a pain specialist or an addiction specialist, or both, might be needed, depending on the patient’s condition at any given follow-up visit. Such referral decisions, as well as all treatment plans, should be documented clearly in the medical record to prevent any misunderstanding, false accusations, or medicolegal repercussions regarding the rationale for continuing or terminating opioid-based treatment.

Non-pharmaceutical therapy for treating pain

The pain management field has successfully integrated the biopsychosocial model into regular practice. This model advocates the use of multimodal non-drug interventions in conjunction with opioid and non-opioid medications. Such interventions address behavioral, cognitive, sociocultural (psychosocial), lifestyle, and physiological dimensions of pain. A partial list of non-drug interventions is provided in Table 5.

Integration of these interventions within a biopsychosocial framework can assist you in making a comprehensive treatment plan. For example, patients with focal myofascial shoulder and back pain might derive only transient benefit from trigger point injection. However, concurrent referral to a pain psychologist and physical therapist could substantially improve functional outcomes by addressing factors that directly and indirectly influence myofascial pain. Inclusion of cognitive-behavioral therapy (addressing psychosocial and lifestyle dimensions), surface electromyography, psychophysiological interventions/biofeedback (addressing psychosocial, lifestyle, and physiological dimensions), and physical therapy (addressing lifestyle and physiological dimensions) allows the patient to learn coping skills, decrease physiological arousal that can lead to unnecessary tensing of muscles, and strengthen core muscle groups.

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20 Files/2011/Relieving-Pain-in-America-A-Blueprint-for- Transforming-Prevention-Care-Education-Research/ Pain%20Research%202011%20Report%20Brief.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed April 15, 2015.

2. Jensen MP, Moore MR, Bockow TB, et al. Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in persons with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(1):146-160.

3. McCarron R, Xiong G, Bourgeois J. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

4. Abrishami A, Khajehdehi A, Chung F. A systematic review of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):423-438.

5. Boynton G, Vahabzadeh A, Hammoud S, et al. Validation of the STOP-BANG questionnaire among patients referred for suspected obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Disord Treat Care. 2013;2(4). doi: 10.4172/2325-9639.1000121.

6. Vana KD, Silva GE, Goldberg R. Predictive abilities of the STOP-Bang and Epworth Sleepiness Scale in identifying sleep clinic patients at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36(1):84-94.

7. Chung F, Elsaid H. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea before surgery: why is it important? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22(3):405-411.

8. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812-821.

9. Forman JP, Rimm EB, Curhan GC. Frequency of analgesic use and risk of hypertension among men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):394-399.

10. Sudano I, Flammer AJ, Périat D, et al. Acetaminophen increases blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1789-1796.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Questions and answers about oral prescription acetaminophen products to be limited to 325 mg per dosage unit. http://www.fda.gov/ drugs/drugsafety/informationbydrugclass/ucm239871. htm. Updated December 11, 2014. Accessed February 23, 2015.

12. Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al; Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):769-779.

13. Sullivan MD, Robinson JP. Antidepressant and anticonvulsant medication for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2006;17(2):381-400, vi-vii.

14. Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, et al. Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;96(6):399-409.

15. Pilowsky I, Hallett EC, Bassett DL, et al. A controlled study of amitriptyline in the treatment of chronic pain. Pain. 1982;14(2):169-179.

16. Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150(3):573-581.

17. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

18. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. An update of comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in chronic spinal pain. Part II: guidance and recommendations. Pain Physician. 2013;16(suppl 2):S49-S283.

19. Singh V, Trescot A, Nishio I. Injections for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):249-261.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers— United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492.

21. Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657-659.

22. Chen L, Vo T, Seefeld L, et al. Lack of correlation between opioid dose adjustment and pain score change in a group of chronic pain patients. J Pain. 2013;14(4):384-392.

23. Federation of State Medical Boards. Model policy for the use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of chronic pain. http:// www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/ pain_policy_july2013.pdf. Published July 2013. Accessed December 18, 2015.

24. Passik SD, Weinreb HJ. Managing chronic nonmalignant pain: overcoming obstacles to the use of opioids. Adv Ther. 2000;17(2):70-83.

Pain is one of the most common symptoms for which patients seek medical care, with an associated estimated annual cost of $600 billion.1 Using a multimodal approach to care—thorough evaluation, cognitive-behavioral and psychophysiological therapy, physical therapy, medications, and other interventions—can help patients effectively manage their condition and achieve healthier outcomes.

Evaluating a patient with pain

When developing a safe, comprehensive, and effective treatment plan for patients with chronic pain, first perform a thorough history and physical exam using the following elements:

Pain history. The PQRST mnemonic (Table 1) can help you obtain critical information and assist in determining the appropriate diagnosis and cause of the patient’s pain complaints.

Psychiatric history. Document the mental health history of the patient and first-degree relatives.

Medical history. Knowing the medical history could reveal comorbidities contributing to a patient’s pain complaint.

Treatment history. Listing past and current treatments for pain, including effectiveness, helps the clinician understand if an existing treatment plan should be modified.

Functional status. Document current level of daily activity, how life activities are affected by pain; strategies used to help cope with pain; level of physical and emotional support provided in home, work, and school environments; and active stressors (eg, financial, interpersonal).

Psychosocial history. Document historical information related to coping skills, trauma history, family of origin, abuse, interpersonal relationships, social support, and academic and vocational functioning.

Substance use or abuse. Assess for use of controlled substances (ie, early refills; lost medications; obtaining medications from multiple prescribers, friends, families, or strangers; use of prescribed and non-prescribed medications for non-medical and medical purposes), nicotine, alcohol, illicit substances, and caffeine. A thorough inventory can help to identify substances a patient is using that could affect daily functioning and pain level.

Behavioral observations. Assessing mental status (eg, insight, pain behavior, cooperation) can be useful. Paying attention to pain behaviors, such as complaints of pain, decreased activity, increased medication intake, or altered facial expressions or body posture, can help the clinician gain insight to the extent that pain affects the patient’s quality of life.

The information gathered in the patient evaluation can be used to design a multimodal treatment plan to achieve maximum effectiveness.

Assessing psychiatric illness

Current approaches to pain evaluation and treatment recommend use of a biopsychosocial orientation because psychological, behavioral, and social factors can influence the experience and impact of pain, regardless of the primary cause.2 A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment plan should consider the broader context in which a patient’s pain occurs.

Regarding psychiatric illness, past and current symptoms, treatment history, and risk assessment should all be included. Using the “AMPS approach” (Figure)3—assessing Anxiety, Mood (depression and mania), Psychotic symptoms (paranoid ideation and hallucinations), and Substance use—helps screen for comorbid psychiatric conditions in patients with chronic pain.

Sleep assessment

Chronic pain patients often experience significant sleep disturbance that could be caused by physiological aspects of the pain condition, environmental factors (eg, uncomfortable bedding), a comorbid sleep disorder (eg, sleep apnea), a psychiatric disorder, or a combination of the above.

Obstructive and central sleep apnea are characterized by nighttime hypoxia, which leads to frequent disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and often manifests as daytime fatigue, irritability, depression, drowsiness, headaches, and increased pain sensitivity. Changes in sleep arousal can lead to neuropsychological changes during the day, such as decreased attention, memory problems, impaired executive functioning, and reduced impulse control.

Screen patients for central and obstructive sleep apnea before prescribing opioids or benzodiazepines for pain because these medications can cause or exacerbate underlying sleep apnea. Although many screening tools, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, assess daytime somnolence,4 the STOP-BANG questionnaire is a quick, validated, and efficient screening tool that often is used to assess sleep apnea risk5,6 (Table 2). The presence of ≥3 risk factors identifies patients at increased risk and warrants consideration for further workup by a sleep specialist.7,8

Pharmacotherapy for chronic pain

Non-opioid medications. Pain can be broadly categorized as neuropathic or nociceptive. Neuropathic pain can be described by patients as numbness, burning, electric-like, and tingling, and is associated with nerve damage. Nociceptive pain commonly is described as similar to a toothache with descriptors such as stabbing, sharp, or a dull aching sensation; it is often, but not always, associated with acute injury or ongoing trauma to tissue. Drug treatment is most successful when the appropriate class of medication is matched to the specific type of pain.

Nociceptive pain often is successfully treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen. Non-selective COX inhibitors (eg, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac) and COX-2 selective inhibitors (eg, celecoxib) have been associated with cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and renal disease; acetaminophen is associated with liver dysfunction.9-11 However, the absolute risk for complications in healthy patients is low.12 To minimize risk, use these agents for the shortest duration and at the lowest effective dosage possible.

Neuropathic pain can be addressed with certain antidepressants13—specifically, those that increase serotonin and norepinephrine (eg, tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs] and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs]), or medications that block ion channels (eg, anticonvulsants). TCAs (eg, desipramine, nortriptyline, amitriptyline) are among the best studied and most cost effective medications for treating neuropathic pain,14,15 but they can have sedating and anticholinergic effects, as well as cardiac adverse effects (ie, prolongation of the QTc interval). SNRIs (eg, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran) can be effective and often are better tolerated than TCAs.14

Some newer anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin and pregabalin) have been found to be more effective than placebo for a variety of neuropathic pain conditions.16,17 Although they have few drug-drug interactions, anticonvulsants can cause dizziness, forgetfulness, and sedation. These adverse effects can be minimized by starting at a low dosage and titrating carefully. Because hepatic or renal impairment can affect metabolism or excretion of these drugs, review the prescribing information to determine safe dosing.

Targeted injection of medications to major pain generators (eg, an epidural steroid for radicular neck and back pain; facet injections for facet-related neck and back pain; trigger point injections for myofascial pain; occipital nerve blocks for occipital neuralgia; and botulinum toxin A injections for chronic migraine headache) can be effective in reducing discomfort and increasing function in patients with chronic pain. A detailed discussion of such therapies is beyond the scope of this article, but have been reviewed extensively elsewhere.18,19

Opioids. Although there is little evidence of long-term efficacy with chronic opioid therapy for most patients, a trial of opioids might be warranted for select patients who do not respond to other medications. Because the risk–benefit ratio for chronic opioid therapy is high,20-22 a decision to initiate a trial of a low-dosage opioid should be made only after careful consideration of those risks. It is generally agreed that treatment of chronic pain with low-dosage opioid therapy is more likely to be successful when it is used as an adjuvant to non-opioid modalities (eg, physical reconditioning, injection therapies, spinal cord stimulation, neurobehavioral interventions, non-opioid medications).

The Federation of State Medical Boards has stated that excessive reliance on opioid medications for treating chronic pain is a deviation from best practices.23 To maximize benefit and minimize risk, clinicians should carefully select appropriate patients, establish functional goals, and regularly monitor for efficacy and compliance. Thoroughly document these steps in the patient’s record for later reference.23

After establishing a clinical diagnosis for the cause of the pain, you should determine the risk of opioid abuse or misuse by using any one of the available risk assessment tools (Box). Understand, however, that no single tool has been shown to be more effective than others.

Although patients and some clinicians tend to overvalue the benefits of chronic opioid therapy, many do not fully appreciate the risks (eg, respiratory depression and death), which can be exacerbated if the patient is using other substance that suppress respiration (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, and illicit substances). Written informed consent and treatment agreement is highly recommended; components of such a document are listed in Table 3.23

Develop a treatment plan that emphasizes functional goals based on the patient’s physical limitations and that incorporates some type of daily, atraumatic physical activity. This plan should be documented and reviewed regularly to help monitor treatment effectiveness.

After an initial trial of a few weeks, the patient and clinician should meet to review the 5 “A”s (Table 4)24 to determine the success of the opioid regimen. Consulting your state’s prescription drug monitoring program (if one is available), obtaining a random urine drug test, and doing a pill count can provide useful, objective data. If the patient has not made progress but has experienced no adverse effects, then a small dosage increase might be warranted. If any of the 5 “A”s indicates lack of improvement or increased risk, consider stopping opioid therapy and exploring non-opioid options to manage chronic pain.

Referrals to a pain specialist or an addiction specialist, or both, might be needed, depending on the patient’s condition at any given follow-up visit. Such referral decisions, as well as all treatment plans, should be documented clearly in the medical record to prevent any misunderstanding, false accusations, or medicolegal repercussions regarding the rationale for continuing or terminating opioid-based treatment.

Non-pharmaceutical therapy for treating pain

The pain management field has successfully integrated the biopsychosocial model into regular practice. This model advocates the use of multimodal non-drug interventions in conjunction with opioid and non-opioid medications. Such interventions address behavioral, cognitive, sociocultural (psychosocial), lifestyle, and physiological dimensions of pain. A partial list of non-drug interventions is provided in Table 5.

Integration of these interventions within a biopsychosocial framework can assist you in making a comprehensive treatment plan. For example, patients with focal myofascial shoulder and back pain might derive only transient benefit from trigger point injection. However, concurrent referral to a pain psychologist and physical therapist could substantially improve functional outcomes by addressing factors that directly and indirectly influence myofascial pain. Inclusion of cognitive-behavioral therapy (addressing psychosocial and lifestyle dimensions), surface electromyography, psychophysiological interventions/biofeedback (addressing psychosocial, lifestyle, and physiological dimensions), and physical therapy (addressing lifestyle and physiological dimensions) allows the patient to learn coping skills, decrease physiological arousal that can lead to unnecessary tensing of muscles, and strengthen core muscle groups.

Pain is one of the most common symptoms for which patients seek medical care, with an associated estimated annual cost of $600 billion.1 Using a multimodal approach to care—thorough evaluation, cognitive-behavioral and psychophysiological therapy, physical therapy, medications, and other interventions—can help patients effectively manage their condition and achieve healthier outcomes.

Evaluating a patient with pain

When developing a safe, comprehensive, and effective treatment plan for patients with chronic pain, first perform a thorough history and physical exam using the following elements:

Pain history. The PQRST mnemonic (Table 1) can help you obtain critical information and assist in determining the appropriate diagnosis and cause of the patient’s pain complaints.

Psychiatric history. Document the mental health history of the patient and first-degree relatives.

Medical history. Knowing the medical history could reveal comorbidities contributing to a patient’s pain complaint.

Treatment history. Listing past and current treatments for pain, including effectiveness, helps the clinician understand if an existing treatment plan should be modified.

Functional status. Document current level of daily activity, how life activities are affected by pain; strategies used to help cope with pain; level of physical and emotional support provided in home, work, and school environments; and active stressors (eg, financial, interpersonal).

Psychosocial history. Document historical information related to coping skills, trauma history, family of origin, abuse, interpersonal relationships, social support, and academic and vocational functioning.

Substance use or abuse. Assess for use of controlled substances (ie, early refills; lost medications; obtaining medications from multiple prescribers, friends, families, or strangers; use of prescribed and non-prescribed medications for non-medical and medical purposes), nicotine, alcohol, illicit substances, and caffeine. A thorough inventory can help to identify substances a patient is using that could affect daily functioning and pain level.

Behavioral observations. Assessing mental status (eg, insight, pain behavior, cooperation) can be useful. Paying attention to pain behaviors, such as complaints of pain, decreased activity, increased medication intake, or altered facial expressions or body posture, can help the clinician gain insight to the extent that pain affects the patient’s quality of life.

The information gathered in the patient evaluation can be used to design a multimodal treatment plan to achieve maximum effectiveness.

Assessing psychiatric illness

Current approaches to pain evaluation and treatment recommend use of a biopsychosocial orientation because psychological, behavioral, and social factors can influence the experience and impact of pain, regardless of the primary cause.2 A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment plan should consider the broader context in which a patient’s pain occurs.

Regarding psychiatric illness, past and current symptoms, treatment history, and risk assessment should all be included. Using the “AMPS approach” (Figure)3—assessing Anxiety, Mood (depression and mania), Psychotic symptoms (paranoid ideation and hallucinations), and Substance use—helps screen for comorbid psychiatric conditions in patients with chronic pain.

Sleep assessment

Chronic pain patients often experience significant sleep disturbance that could be caused by physiological aspects of the pain condition, environmental factors (eg, uncomfortable bedding), a comorbid sleep disorder (eg, sleep apnea), a psychiatric disorder, or a combination of the above.

Obstructive and central sleep apnea are characterized by nighttime hypoxia, which leads to frequent disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and often manifests as daytime fatigue, irritability, depression, drowsiness, headaches, and increased pain sensitivity. Changes in sleep arousal can lead to neuropsychological changes during the day, such as decreased attention, memory problems, impaired executive functioning, and reduced impulse control.

Screen patients for central and obstructive sleep apnea before prescribing opioids or benzodiazepines for pain because these medications can cause or exacerbate underlying sleep apnea. Although many screening tools, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, assess daytime somnolence,4 the STOP-BANG questionnaire is a quick, validated, and efficient screening tool that often is used to assess sleep apnea risk5,6 (Table 2). The presence of ≥3 risk factors identifies patients at increased risk and warrants consideration for further workup by a sleep specialist.7,8

Pharmacotherapy for chronic pain

Non-opioid medications. Pain can be broadly categorized as neuropathic or nociceptive. Neuropathic pain can be described by patients as numbness, burning, electric-like, and tingling, and is associated with nerve damage. Nociceptive pain commonly is described as similar to a toothache with descriptors such as stabbing, sharp, or a dull aching sensation; it is often, but not always, associated with acute injury or ongoing trauma to tissue. Drug treatment is most successful when the appropriate class of medication is matched to the specific type of pain.

Nociceptive pain often is successfully treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen. Non-selective COX inhibitors (eg, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac) and COX-2 selective inhibitors (eg, celecoxib) have been associated with cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and renal disease; acetaminophen is associated with liver dysfunction.9-11 However, the absolute risk for complications in healthy patients is low.12 To minimize risk, use these agents for the shortest duration and at the lowest effective dosage possible.

Neuropathic pain can be addressed with certain antidepressants13—specifically, those that increase serotonin and norepinephrine (eg, tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs] and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs]), or medications that block ion channels (eg, anticonvulsants). TCAs (eg, desipramine, nortriptyline, amitriptyline) are among the best studied and most cost effective medications for treating neuropathic pain,14,15 but they can have sedating and anticholinergic effects, as well as cardiac adverse effects (ie, prolongation of the QTc interval). SNRIs (eg, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran) can be effective and often are better tolerated than TCAs.14

Some newer anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin and pregabalin) have been found to be more effective than placebo for a variety of neuropathic pain conditions.16,17 Although they have few drug-drug interactions, anticonvulsants can cause dizziness, forgetfulness, and sedation. These adverse effects can be minimized by starting at a low dosage and titrating carefully. Because hepatic or renal impairment can affect metabolism or excretion of these drugs, review the prescribing information to determine safe dosing.

Targeted injection of medications to major pain generators (eg, an epidural steroid for radicular neck and back pain; facet injections for facet-related neck and back pain; trigger point injections for myofascial pain; occipital nerve blocks for occipital neuralgia; and botulinum toxin A injections for chronic migraine headache) can be effective in reducing discomfort and increasing function in patients with chronic pain. A detailed discussion of such therapies is beyond the scope of this article, but have been reviewed extensively elsewhere.18,19

Opioids. Although there is little evidence of long-term efficacy with chronic opioid therapy for most patients, a trial of opioids might be warranted for select patients who do not respond to other medications. Because the risk–benefit ratio for chronic opioid therapy is high,20-22 a decision to initiate a trial of a low-dosage opioid should be made only after careful consideration of those risks. It is generally agreed that treatment of chronic pain with low-dosage opioid therapy is more likely to be successful when it is used as an adjuvant to non-opioid modalities (eg, physical reconditioning, injection therapies, spinal cord stimulation, neurobehavioral interventions, non-opioid medications).

The Federation of State Medical Boards has stated that excessive reliance on opioid medications for treating chronic pain is a deviation from best practices.23 To maximize benefit and minimize risk, clinicians should carefully select appropriate patients, establish functional goals, and regularly monitor for efficacy and compliance. Thoroughly document these steps in the patient’s record for later reference.23

After establishing a clinical diagnosis for the cause of the pain, you should determine the risk of opioid abuse or misuse by using any one of the available risk assessment tools (Box). Understand, however, that no single tool has been shown to be more effective than others.

Although patients and some clinicians tend to overvalue the benefits of chronic opioid therapy, many do not fully appreciate the risks (eg, respiratory depression and death), which can be exacerbated if the patient is using other substance that suppress respiration (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, and illicit substances). Written informed consent and treatment agreement is highly recommended; components of such a document are listed in Table 3.23

Develop a treatment plan that emphasizes functional goals based on the patient’s physical limitations and that incorporates some type of daily, atraumatic physical activity. This plan should be documented and reviewed regularly to help monitor treatment effectiveness.

After an initial trial of a few weeks, the patient and clinician should meet to review the 5 “A”s (Table 4)24 to determine the success of the opioid regimen. Consulting your state’s prescription drug monitoring program (if one is available), obtaining a random urine drug test, and doing a pill count can provide useful, objective data. If the patient has not made progress but has experienced no adverse effects, then a small dosage increase might be warranted. If any of the 5 “A”s indicates lack of improvement or increased risk, consider stopping opioid therapy and exploring non-opioid options to manage chronic pain.

Referrals to a pain specialist or an addiction specialist, or both, might be needed, depending on the patient’s condition at any given follow-up visit. Such referral decisions, as well as all treatment plans, should be documented clearly in the medical record to prevent any misunderstanding, false accusations, or medicolegal repercussions regarding the rationale for continuing or terminating opioid-based treatment.

Non-pharmaceutical therapy for treating pain

The pain management field has successfully integrated the biopsychosocial model into regular practice. This model advocates the use of multimodal non-drug interventions in conjunction with opioid and non-opioid medications. Such interventions address behavioral, cognitive, sociocultural (psychosocial), lifestyle, and physiological dimensions of pain. A partial list of non-drug interventions is provided in Table 5.

Integration of these interventions within a biopsychosocial framework can assist you in making a comprehensive treatment plan. For example, patients with focal myofascial shoulder and back pain might derive only transient benefit from trigger point injection. However, concurrent referral to a pain psychologist and physical therapist could substantially improve functional outcomes by addressing factors that directly and indirectly influence myofascial pain. Inclusion of cognitive-behavioral therapy (addressing psychosocial and lifestyle dimensions), surface electromyography, psychophysiological interventions/biofeedback (addressing psychosocial, lifestyle, and physiological dimensions), and physical therapy (addressing lifestyle and physiological dimensions) allows the patient to learn coping skills, decrease physiological arousal that can lead to unnecessary tensing of muscles, and strengthen core muscle groups.

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20 Files/2011/Relieving-Pain-in-America-A-Blueprint-for- Transforming-Prevention-Care-Education-Research/ Pain%20Research%202011%20Report%20Brief.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed April 15, 2015.

2. Jensen MP, Moore MR, Bockow TB, et al. Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in persons with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(1):146-160.

3. McCarron R, Xiong G, Bourgeois J. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

4. Abrishami A, Khajehdehi A, Chung F. A systematic review of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):423-438.

5. Boynton G, Vahabzadeh A, Hammoud S, et al. Validation of the STOP-BANG questionnaire among patients referred for suspected obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Disord Treat Care. 2013;2(4). doi: 10.4172/2325-9639.1000121.

6. Vana KD, Silva GE, Goldberg R. Predictive abilities of the STOP-Bang and Epworth Sleepiness Scale in identifying sleep clinic patients at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36(1):84-94.

7. Chung F, Elsaid H. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea before surgery: why is it important? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22(3):405-411.

8. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812-821.

9. Forman JP, Rimm EB, Curhan GC. Frequency of analgesic use and risk of hypertension among men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):394-399.

10. Sudano I, Flammer AJ, Périat D, et al. Acetaminophen increases blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1789-1796.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Questions and answers about oral prescription acetaminophen products to be limited to 325 mg per dosage unit. http://www.fda.gov/ drugs/drugsafety/informationbydrugclass/ucm239871. htm. Updated December 11, 2014. Accessed February 23, 2015.

12. Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al; Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):769-779.

13. Sullivan MD, Robinson JP. Antidepressant and anticonvulsant medication for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2006;17(2):381-400, vi-vii.

14. Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, et al. Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;96(6):399-409.

15. Pilowsky I, Hallett EC, Bassett DL, et al. A controlled study of amitriptyline in the treatment of chronic pain. Pain. 1982;14(2):169-179.

16. Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150(3):573-581.

17. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

18. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. An update of comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in chronic spinal pain. Part II: guidance and recommendations. Pain Physician. 2013;16(suppl 2):S49-S283.

19. Singh V, Trescot A, Nishio I. Injections for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):249-261.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers— United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492.

21. Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657-659.

22. Chen L, Vo T, Seefeld L, et al. Lack of correlation between opioid dose adjustment and pain score change in a group of chronic pain patients. J Pain. 2013;14(4):384-392.

23. Federation of State Medical Boards. Model policy for the use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of chronic pain. http:// www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/ pain_policy_july2013.pdf. Published July 2013. Accessed December 18, 2015.

24. Passik SD, Weinreb HJ. Managing chronic nonmalignant pain: overcoming obstacles to the use of opioids. Adv Ther. 2000;17(2):70-83.

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20 Files/2011/Relieving-Pain-in-America-A-Blueprint-for- Transforming-Prevention-Care-Education-Research/ Pain%20Research%202011%20Report%20Brief.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed April 15, 2015.

2. Jensen MP, Moore MR, Bockow TB, et al. Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in persons with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(1):146-160.

3. McCarron R, Xiong G, Bourgeois J. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

4. Abrishami A, Khajehdehi A, Chung F. A systematic review of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):423-438.

5. Boynton G, Vahabzadeh A, Hammoud S, et al. Validation of the STOP-BANG questionnaire among patients referred for suspected obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Disord Treat Care. 2013;2(4). doi: 10.4172/2325-9639.1000121.

6. Vana KD, Silva GE, Goldberg R. Predictive abilities of the STOP-Bang and Epworth Sleepiness Scale in identifying sleep clinic patients at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36(1):84-94.

7. Chung F, Elsaid H. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea before surgery: why is it important? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22(3):405-411.

8. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812-821.

9. Forman JP, Rimm EB, Curhan GC. Frequency of analgesic use and risk of hypertension among men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):394-399.

10. Sudano I, Flammer AJ, Périat D, et al. Acetaminophen increases blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1789-1796.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Questions and answers about oral prescription acetaminophen products to be limited to 325 mg per dosage unit. http://www.fda.gov/ drugs/drugsafety/informationbydrugclass/ucm239871. htm. Updated December 11, 2014. Accessed February 23, 2015.

12. Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al; Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):769-779.

13. Sullivan MD, Robinson JP. Antidepressant and anticonvulsant medication for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2006;17(2):381-400, vi-vii.

14. Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, et al. Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;96(6):399-409.

15. Pilowsky I, Hallett EC, Bassett DL, et al. A controlled study of amitriptyline in the treatment of chronic pain. Pain. 1982;14(2):169-179.

16. Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150(3):573-581.

17. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

18. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. An update of comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in chronic spinal pain. Part II: guidance and recommendations. Pain Physician. 2013;16(suppl 2):S49-S283.

19. Singh V, Trescot A, Nishio I. Injections for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):249-261.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers— United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492.

21. Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657-659.

22. Chen L, Vo T, Seefeld L, et al. Lack of correlation between opioid dose adjustment and pain score change in a group of chronic pain patients. J Pain. 2013;14(4):384-392.

23. Federation of State Medical Boards. Model policy for the use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of chronic pain. http:// www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/ pain_policy_july2013.pdf. Published July 2013. Accessed December 18, 2015.

24. Passik SD, Weinreb HJ. Managing chronic nonmalignant pain: overcoming obstacles to the use of opioids. Adv Ther. 2000;17(2):70-83.

Assessing head pain

Head pain and psychiatric illness: Applying the biopsychosocial model to care

More than 45% of people worldwide suffer from headache at some point in their life.1 Head pain can lead to disability and functional decline, yet headache disorders often are underdiagnosed and poorly assessed. For example, 60% of migraine and tension-type headaches go undiagnosed and 50% of persons suffering from migraine have severe functional disability or require bed rest.2-4

Because head pain can be associated with secondary medical and psychiatric conditions, diagnosis can be challenging. This article reviews the medical and psychological aspects of major headaches and assists with clinical assessment. We present clinical interviewing tools and a diagram to enhance focused, efficient assessment and inform treatment plans.

Classification of headache

Headache is a common complaint, yet it is often underdiagnosed and ineffectively treated. The World Health Organization estimates that, globally, 50% of people with headache self-treat their pain.5 The International Headache Society classifies headache as primary or secondary; approximately 90% of complaints are from primary headache.6

Assessment and diagnosis of headache can be complex because of overlapping, subjective symptoms. It is important to have a general understanding of primary and secondary causes of headache so that interrelated symptoms do not obscure the most accurate diagnosis and effective treatment course. Although most headache complaints are benign, ruling out secondary causes helps gauge the likelihood of developing severe sequelae from underlying pathology.

By definition, primary headaches are idiopathic and commonly include migraine, tension-type, cluster, and hemicrania continua headache. Secondary headaches have an underlying pathology, which could improve by targeting the disorder. Common secondary causes of headache include:

• trauma

• vascular abnormalities

• structural abnormalities

• chemical (including medications)

• inflammation or infection

• metabolic conditions

• diseases of the neck and pericranial and intracranial structures

• psychiatric conditions.

Table 1 illustrates common causes of head pain. More definitive criteria for symptoms and diagnosis can be found in the International Classification of Headache Disorders.7

Primary headache

Tension-type is the most common primary headache, accounting for more than one-half of all headaches.7 Patients usually describe a tight pain in a bilateral band-like distribution, which could be caused by sustained neck muscle contraction. Pain usually builds in intensity and can last 30 minutes to several days. There is a well-established association between emotional stress or depression and the development of tension-type headaches.8

Migraine typically causes pulsating pain in a localized area of the head that lasts as long as 72 hours and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phono-phobia, and aura. Patients report varying precipitating factors but commonly cite certain foods, menstruation, and sleep deprivation. Although rare, migraine with aura has been linked to ischemic stroke; most cases have been reported in female smokers and oral contraceptive users age <45.9

Because migraines can be debilitating, some patients—typically those with ≥4 attacks a month—opt for prophylactic medication. Effective prophylactics include amitriptyline, propranolol, divalproex sodium, and topiramate, which should be monitored closely and given a trial for several months before switching to another drug. Commonly used abortive treatments include triptans and anti-emetics such as metoclopramide.

Meperidine and ketorolac are popular second-line agents for migraine. Botulinum toxin A also has been used in severe cases to reduce the number of headache days in chronic migraine patients.6

Cluster headache is rare, but typically exhibits repeated burning and intense unilateral periorbital or retro-orbital pain that lasts 15 minutes to 3 hours over several weeks. Men are predominantly affected. Cluster headaches typically improve with oxygen treatment.

Biopsychosocial model of head pain

The biomedical model has helped iden tify pathophysiological pain mechanisms and pharmacotherapeutic agents for headache. However, during assessment, limiting one’s attention to the linear relationship between pathology, mechanism of action, and pain oversimplifies common questions clinicians face when assessing chronic head pain.

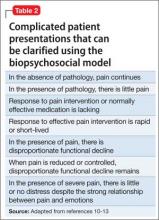

Advancements in the last 3 decades have expanded the conceptualization of head pain to integrate sociocultural, environmental, behavioral, affective, cognitive, and biological variables—otherwise known as the biopsychosocial model.10,11 The biopsychosocial model is a multidimensional theory that helps answer difficult clinical assessment questions and complex patient presentations (Table 2).10-13 Many unusual responses to pain treatment, questionable validity of pain behavior, and disproportionate pain perception and functional decline are explained by non-pathophysiological and non-biomechanical models.

Psychiatric comorbidity and head pain

Psychiatric conditions are highly prevalent among persons with primary headache. Verri et al14 found that 90% of chronic daily headache patients had ≥1 psychiatric condition; depression and anxiety were most common. Of concern, 1 study found that headache is associated with increased frequency of suicidal ideation among patients with chronic pain.15 It is critical for clinicians to screen for psychiatric comorbidities in patients with chronic headache. Conversely, clinicians might want to screen for headache in their patients with psychiatric illness.

Migraine. Mood disorders are common among patients who suffer from migraine. The rate of depression is 2 to 4 times higher in those with migraine compared with healthy controls.16,17 In a large-scale study, patients with migraine had a 1.9-fold higher risk (compared with controls) of having a comorbid depressive episode; a 2-fold higher risk of manic episodes; and a 3-fold higher risk of both mania and depression.18 In a study of 62 inpatients, Fasmer19 reported that 46% of patients with unipolar depression and 44% of patients with bipolar disorder experienced migraine (77% of the bipolar disorder patients with migraine had bipolar II disorder). Patients with migraine are at increased risk of suicide attempts (odds ratio 4.3; 95% CI, 1.2-15.7).20

Tension-type headache. The relationship between psychiatric comorbidity in tension-type headache is well established. In contrast to what is seen with migraines, Puca et al21 found a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders (52.5%) than depressive disorders (36.4%) in patients with tension-type headache. Generalized anxiety disorder was one of the most prevalent anxiety conditions (83.3%), and dysthymia was the most prevalent mood disorder (45.6%). In the same study, 21.7% of patients were found to have a comorbid somatoform disorder.21

Emotional and cognitive factors can co-occur in patients with tension-type headache and a comorbid psychiatric condition. For example, difficulty identifying or recognizing emotions—commonly referred to as alexithymia—has been linked to tension-type headache.22 Additionally, maladaptive cognitive appraisal of stress is more common among patients with tension-type headache when compared with those without headaches.23 Being mindful of and recognizing these co-occurring emotional and cognitive factors will help clinicians construct a more accurate assessment and effective behavioral treatment plan.

Clinical assessment with a useful mnemonic

Clinical assessment of psychiatric illness is essential when evaluating chronic pain patients. Using the acronym AMPS (Anxiety, Mood, Psychosis, and Substance use disorders) (Table 3) is an efficient way for the clinician to ask pertinent questions regarding common psychiatric conditions that could have a direct effect on chronic pain.24 Head pain can be more intense when combined with untreated anxiety, depression, psychosis, or a substance use disorder. Untreated anxiety, for example, can amplify sympathetic response to pain and complicate treatment.

Investigating head pain patients for an underlying mood disorder is essential to providing successful treatment. Consider:

• starting psychotherapy modalities that address both pain and psychiatric illness, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

• reframing unhelpful pain beliefs

• managing activity-rest levels

• biofeedback

• supportive group therapy

• reducing family members’ reinforcement of the patient’s pain behavior or sick role.25

Assessing for somatic symptom disorders

In addition to using the AMPS approach for psychiatric assessment, clinicians should evaluate for somatization, which can present as head pain. Somatic symptom disorders (SSD) are a class of conditions that are impacted by affective, cognitive, and reinforcing factors that might or might not be consciously or intentionally produced. Patients with an SSD have somatic symptoms that are distressing or cause significant disruption of daily life because of excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to the somatic symptoms, for ≥6 months. The Figure outlines SSD, related conditions, and their respective prominent symptoms to assist in the differential diagnosis.26

Note that some headache conditions present with severe distress because of their abrupt onset and severity of symptoms (eg, cluster headaches). Therefore, the expectation and likelihood of psychological disturbance should be factored into a diagnosis of SSD and related conditions as seen in the Figure.

Secondary factors of unusual pain behavior or treatment response. The role of thoughts, affect, and behaviors is clinically meaningful in understanding SSD and similar conditions. Specific questions about cultural beliefs and rituals as they relate to exacerbations of head pain are of value. Table 413,27 lists behavioral, cognitive, and affective dimensions of head pain using the biopsychosocial model, and further clarifies common questions that arise with unusual pain response and complex patient presentations, which were outlined in the beginning of the article.

Because depression and anxiety can be comorbid with head pain, it is important to recognize psychological factors that contribute to pain perception. Indifference or denial of emotional stress as a result of severe pain and disability can imply a somatization process, which could suggest emotional disconnection or dissociation from somatic functioning.28 This finding can be a component of alexithymia, in which a person is disconnected from emotions and how emotions impact the body. Therefore, recognizing alexithymia assists in identifying psychological factors when patients deny mood symptoms, particularly in tension-type headache.

Functional assessment to rule out the disproportional impact of pain on daily activities is helpful in understanding the somatization process. Neurocognitive functioning should be assessed, particularly because frontal and subcortical dysregulation has been observed in head pain sufferers.29,30 Patients with cognitive changes as a result of a medical illness (eg, stroke, head concussion, brain tumor, or seizures) are especially at risk for neurocognitive dysfunction.

Neuropsychological assessment can be useful, not only to assess neurocognitive functioning (eg, Repeated Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status) but to identify objective test profiles associated with altered motivation (eg, Rey 15-Item Test, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Form F Scale, Personality Assessment Inventory [PAI] Negative Impression Management) and somatization processes (eg, PAI Somatization Scale). These instruments help to identify the severity of psychiatric and neurocognitive symptoms by comparing scores to normative (eg, healthy control group), clinical (eg, somatization, traumatic brain injury, mild cognitive impairment), and altered motivation (eg, persons instructed to exaggerate symptoms) databases.

If the clinician pursues neurocognitive assessment, direct referral to a neuropsychologist, referral to neurologist, or administration of a cognitive screening tool such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Saint Louis University Mental Status, or Cognitive Log is recommended. If the cognitive screening is positive, next steps include: referring for full neuropsychological assessment, which includes complete cognitive and motor testing, personality testing, and integration of neuroimaging data (eg, MRI, CT scans, and/or EEG).

Assessing the patients’ self-talk or thought patterns as they describe their head pain will help clinicians understand belief systems that may be distorting the reality of the medical condition. For example, a patient might report that “my pain feels like someone is hitting me with an axe”; this is a catastrophic thought that can distort the clarity and perceptibility of pain. Encouraging patients to monitor and analyze their anxiety and associated negative thoughts is an important strategy for improving mood and decreasing somatization. Recording daily thoughts and CBT can help the patient identify and appropriately address his (her) cognitive distortions and futile thinking.

When implementing a treatment plan for somatization disorder, we propose the mnemonic device CARE MD:

• CBT

• Assess (by ruling out a medical cause for somatic complaints)

• Regular visits

• Empathy

• Med-psych interface (help the patient connect physical complaints and emotional stressors)

• Do no harm.

Clinical recommendations

Chronic head pain can be debilitating; psychodiagnostic assessment should therefore be considered an important part of the diagnosis and treatment plan. After ruling out common and emergent primary or secondary causes of head pain, consider psychiatric comorbidities. Depression and anxiety have a strong bidirectional relationship with chronic headache; therefore, we suggest evaluating patients with the intention of alleviating both psychiatric symptoms and head pain.

It is important to diligently assess for common psychiatric comorbidities; using the AMPS and CARE MD mnemonics, along with screening for somatization disorders, is an easy and effective way to evaluate for relevant psychiatric conditions associated with chronic head pain. Because many patients have unusual and complicated responses to head pain that can be explained by non-pathophysiological and non-biomechanical models, using the biopsychosocial model is essential for effective diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Abortive and prophylactic medical interventions, as well as behavioral, sociocultural, and cognitive assessment, are vital to a comprehensive treatment approach.

Bottom Line

The psychodiagnostic assessment can help the astute clinician identify comorbid psychiatric conditions, psychological factors, and somatic symptoms to develop a comprehensive biopsychosocial treatment plan for patients with chronic head pain. Rule out primary and secondary causes of pain and screen for somatization disorders. Consider medication and psychotherapeutic treatment options.

Related Resources

• Pompili M, Di Cosimo D, Innamorati M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic daily headache and migraine: a selective overview including personality traits and suicide risk. J Headache Pain. 2009;10(4):283-290.

• Sinclair AJ, Sturrock A, Davies B, et al. Headache management: pharmacological approaches [published online July 3, 2015]. Pract Neurol. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001167.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Meperidine • Demerol

Botulinum toxin A • Botox Metoclopramide • Reglan

Divalproex sodium • Depakote Propranolol • Inderide

Ketorolac • Toradol Topiramate • Topamax

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):193-210.

2. Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41(7):646-657.

3. The World Health Report 2001: Mental health: new understanding new hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

4. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_ disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf. Published 2004. Accessed July 31, 2015.

5. World Health Organization. Headache disorders. http:// www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs277/en/. Published October 2012. Accessed July 31, 2015.

6. Clinch C. Evaluation & management of headache. In: South- Paul JE, Matheny SC, Lewis EL. eds. Current diagnosis & treatment in family medicine, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015:293-297.

7. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629-808.

8. Mawet J, Kurth T, Ayata C. Migraine and stroke: in search of shared mechanisms. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(2):165-181.

9. Janke EA, Holroyd KA, Romanek K. Depression increases onset of tension-type headache following laboratory stress. Pain. 2004;111(3):230-238.

10. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136.

11. Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(5):535-544.

12. Turk DC, Flor H. Chronic pain: a biobehavioral perspective. In: Gatchel RJ, Turk DC, eds. Psychosocial factors in pain: critical perspectives. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999:18-34.

13. Andrasik F, Flor H, Turk DC. An expanded view of psychological aspects in head pain: the biopsychosocial model. Neurol Sci. 2005;26(suppl 2):s87-s91.

14. Verri AP, Proietti Cecchini A, Galli C, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in chronic daily headache. Cephalalgia. 1998; 18(suppl 21):45-49.

15. Ilgen MA, Zivin K, McCammon RJ, et al. Pain and suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(6):521-527.

16. Kowacs F, Socal MP, Ziomkowski SC, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety, and screening for mental disorders in migrainous patients. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(2):79-89.

17. Hamelsky SW, Lipton RB. Psychiatric comorbidity of migraine. Headache. 2006;46(9):1327-1333.

18. Nguyen TV, Low NC. Comorbidity of migraine and mood episodes in a nationally representative population-based sample. Headache. 2013;53(3):498-506.

19. Fasmer OB. The prevalence of migraine in patients with bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Cephalalgia. 2001; 21(9):894-899.

20. Breslau N. Migraine, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Neurology. 1992;42(2):392-395.

21. Puca F, Genco S, Prudenzano MP, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial stress in patients with tension-type headache from headache centers in Italy. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(3):159-164.

22. Yücel B, Kora K, Ozyalçín S, et al. Depression, automatic thoughts, alexithymia, and assertiveness in patients with tension-type headache. Headache. 2002;42(3):194-199.

23. Wittrock DA, Myers TC. The comparison of individuals with recurrent tension-type headache and headache-free controls in physiological response, appraisal, and coping with stressors: a review of the literature. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20(2):118-134.

24. Onate J, Xiong G, McCarron R. The primary care psychiatric interview. In: McCarron R, Xiong G, Bourgeois J. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2009:3-4.

25. Songer D. Psychotherapeutic approaches in the treatment of pain. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(5):19-24.

26. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

27. Hashmi JA, Baliki MN, Huang L, et al. Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain. 2013;136(pt 9):2751-2768.

28. Packard RC. Conversion headache. Headache. 1980;20(5):266-268.

29. Mongini F, Keller R, Deregibus A, et al. Frontal lobe dysfunction in patients with chronic migraine: a clinical-neuropsychological study. Psychiatry Res. 2005;133(1):101-106.

30. Martelli MF, Grayson RL, Zasler ND. Posttraumatic headache: neuropsychological and psychological effects and treatment implications. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1999;14(1):49-69.

More than 45% of people worldwide suffer from headache at some point in their life.1 Head pain can lead to disability and functional decline, yet headache disorders often are underdiagnosed and poorly assessed. For example, 60% of migraine and tension-type headaches go undiagnosed and 50% of persons suffering from migraine have severe functional disability or require bed rest.2-4

Because head pain can be associated with secondary medical and psychiatric conditions, diagnosis can be challenging. This article reviews the medical and psychological aspects of major headaches and assists with clinical assessment. We present clinical interviewing tools and a diagram to enhance focused, efficient assessment and inform treatment plans.

Classification of headache

Headache is a common complaint, yet it is often underdiagnosed and ineffectively treated. The World Health Organization estimates that, globally, 50% of people with headache self-treat their pain.5 The International Headache Society classifies headache as primary or secondary; approximately 90% of complaints are from primary headache.6

Assessment and diagnosis of headache can be complex because of overlapping, subjective symptoms. It is important to have a general understanding of primary and secondary causes of headache so that interrelated symptoms do not obscure the most accurate diagnosis and effective treatment course. Although most headache complaints are benign, ruling out secondary causes helps gauge the likelihood of developing severe sequelae from underlying pathology.

By definition, primary headaches are idiopathic and commonly include migraine, tension-type, cluster, and hemicrania continua headache. Secondary headaches have an underlying pathology, which could improve by targeting the disorder. Common secondary causes of headache include:

• trauma

• vascular abnormalities

• structural abnormalities

• chemical (including medications)

• inflammation or infection

• metabolic conditions

• diseases of the neck and pericranial and intracranial structures

• psychiatric conditions.

Table 1 illustrates common causes of head pain. More definitive criteria for symptoms and diagnosis can be found in the International Classification of Headache Disorders.7

Primary headache

Tension-type is the most common primary headache, accounting for more than one-half of all headaches.7 Patients usually describe a tight pain in a bilateral band-like distribution, which could be caused by sustained neck muscle contraction. Pain usually builds in intensity and can last 30 minutes to several days. There is a well-established association between emotional stress or depression and the development of tension-type headaches.8

Migraine typically causes pulsating pain in a localized area of the head that lasts as long as 72 hours and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phono-phobia, and aura. Patients report varying precipitating factors but commonly cite certain foods, menstruation, and sleep deprivation. Although rare, migraine with aura has been linked to ischemic stroke; most cases have been reported in female smokers and oral contraceptive users age <45.9

Because migraines can be debilitating, some patients—typically those with ≥4 attacks a month—opt for prophylactic medication. Effective prophylactics include amitriptyline, propranolol, divalproex sodium, and topiramate, which should be monitored closely and given a trial for several months before switching to another drug. Commonly used abortive treatments include triptans and anti-emetics such as metoclopramide.

Meperidine and ketorolac are popular second-line agents for migraine. Botulinum toxin A also has been used in severe cases to reduce the number of headache days in chronic migraine patients.6

Cluster headache is rare, but typically exhibits repeated burning and intense unilateral periorbital or retro-orbital pain that lasts 15 minutes to 3 hours over several weeks. Men are predominantly affected. Cluster headaches typically improve with oxygen treatment.

Biopsychosocial model of head pain

The biomedical model has helped iden tify pathophysiological pain mechanisms and pharmacotherapeutic agents for headache. However, during assessment, limiting one’s attention to the linear relationship between pathology, mechanism of action, and pain oversimplifies common questions clinicians face when assessing chronic head pain.

Advancements in the last 3 decades have expanded the conceptualization of head pain to integrate sociocultural, environmental, behavioral, affective, cognitive, and biological variables—otherwise known as the biopsychosocial model.10,11 The biopsychosocial model is a multidimensional theory that helps answer difficult clinical assessment questions and complex patient presentations (Table 2).10-13 Many unusual responses to pain treatment, questionable validity of pain behavior, and disproportionate pain perception and functional decline are explained by non-pathophysiological and non-biomechanical models.

Psychiatric comorbidity and head pain

Psychiatric conditions are highly prevalent among persons with primary headache. Verri et al14 found that 90% of chronic daily headache patients had ≥1 psychiatric condition; depression and anxiety were most common. Of concern, 1 study found that headache is associated with increased frequency of suicidal ideation among patients with chronic pain.15 It is critical for clinicians to screen for psychiatric comorbidities in patients with chronic headache. Conversely, clinicians might want to screen for headache in their patients with psychiatric illness.

Migraine. Mood disorders are common among patients who suffer from migraine. The rate of depression is 2 to 4 times higher in those with migraine compared with healthy controls.16,17 In a large-scale study, patients with migraine had a 1.9-fold higher risk (compared with controls) of having a comorbid depressive episode; a 2-fold higher risk of manic episodes; and a 3-fold higher risk of both mania and depression.18 In a study of 62 inpatients, Fasmer19 reported that 46% of patients with unipolar depression and 44% of patients with bipolar disorder experienced migraine (77% of the bipolar disorder patients with migraine had bipolar II disorder). Patients with migraine are at increased risk of suicide attempts (odds ratio 4.3; 95% CI, 1.2-15.7).20

Tension-type headache. The relationship between psychiatric comorbidity in tension-type headache is well established. In contrast to what is seen with migraines, Puca et al21 found a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders (52.5%) than depressive disorders (36.4%) in patients with tension-type headache. Generalized anxiety disorder was one of the most prevalent anxiety conditions (83.3%), and dysthymia was the most prevalent mood disorder (45.6%). In the same study, 21.7% of patients were found to have a comorbid somatoform disorder.21

Emotional and cognitive factors can co-occur in patients with tension-type headache and a comorbid psychiatric condition. For example, difficulty identifying or recognizing emotions—commonly referred to as alexithymia—has been linked to tension-type headache.22 Additionally, maladaptive cognitive appraisal of stress is more common among patients with tension-type headache when compared with those without headaches.23 Being mindful of and recognizing these co-occurring emotional and cognitive factors will help clinicians construct a more accurate assessment and effective behavioral treatment plan.

Clinical assessment with a useful mnemonic