User login

Patients with heart failure (HF) present daily to busy EDs. An estimated 6.5 million Americans are living with this diagnosis, and the number is predicted to grow to 8 million by 2023.1 Most HF patients (82.1%) who present to EDs are hospitalized, while a selected minority are either managed in the ED and discharged (11.6%) or managed in observation units (OU) (6.3%).2 The prognosis after HF is initially diagnosed is poor, with a 5-year mortality of 50%,3 and after a single HF hospitalization, 29% will die within 1 year.4

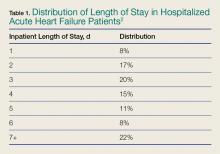

One-third of the total Medicare budget is spent on HF, despite the fact that HF represents only 10.5% of the Medicare population.2 Up to 80% of HF costs are for hospitalizations, which cost an average of $11,840 per inpatient admission.5,6 The high costs are due to an average length of stay (LOS) of 5.2 days7 (Table 1).

Adding to hospital costs is the degree of “reactivism,” with approximately 20% of patients discharged from the ED returning within 2 weeks, of whom nearly 50% will be hospitalized.11 Following HF hospitalization and discharge, the 30-day readmission rate is 26.2%,2 increasing to 36% by 90 days.12 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has incentivized hospitals and providers to reduce admissions, but penalize hospitals that do not. Overall, CMS will reduce payments by up to 3% to hospitals with excess readmissions for select conditions, including HF.13

Causes of Heart Failure

Heart failure represents a final common pathway, which in the United States is most often due to coronary artery disease (CAD). Many types of pathology ultimately result in left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and much of its rising prevalence is a result of the success we now have in managing historically fatal cardiovascular (CV) conditions. These include hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), CAD, and valvular and other CV structural conditions.

Heart failure is caused by either a dilated ventricle with a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and inability to eject volume, or a stiffened ventricle with a preserved EF (HFpEF) that is unable to receive increased venous return. Both conditions acutely decompensate pulmonary congestion. A preserved EF is defined as an EF at or greater than 50%, whereas a reduced EF is at or less than 40%, with the 41% to 49% range considered as borderline preserved EF.3

While there are important differences in the treatment of chronic and subacute HF, driven by the EF, the effect of EF on early decision-making and treatment in the ED is negligible: Although the probability of HFpEF increases with increasing initial ED systolic blood pressure (SBP), clinical presentation and treatment in the ED are initially identical—regardless of the EF.

Noninvasive continuous transcutaneous hemodynamic monitoring is available for ED use, and may provide further insight into the underlying pathophysiology. A study of 127 acute heart failure (AHF) ED patients identified three hemodynamic AHF phenotypes. These include normal cardiac index (CI) and systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI), low CI and SVRI, and low CI and elevated SVRI.14 While it is attractive to suggest therapeutic interventions based on these measurements, outcome data are lacking.

Presentation

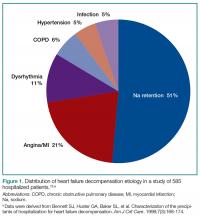

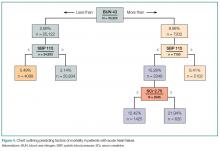

The most common ED presentation of patients suffering from AHF is dyspnea secondary to volume overload, or as the result of acute hypertension with relatively less volume overload. However, regardless of the cause of dyspnea, it is not only the most common resulting complaint, but one that requires immediate treatment. Ultimately, 59% of all HF admissions are attributed to volume overload and dyspnea (Figure 1).15

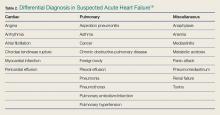

Heart failure can also present in a more protean manner, with cough, fatigue, and edema, as well as more subtle symptoms predominating and resulting in a complicated differential diagnosis (Table 2).16

Because HF is a disease that most significantly affects older patients who frequently have concomitant morbidities (eg, myocardial ischemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] exacerbation, uncontrolled DM), other less clinically obvious disease presentations may actually be the cause of the AHF exacerbation.

Diagnosis

A focused history and physical examination that is part of all ED evaluations should be expedited whenever there is evidence of hemodynamic instability or respiratory compromise. An early working diagnosis is essential to avoid a delay in appropriate treatment, which is associated with increased mortality.

When HF is likely, the potential etiology and precipitants for decompensation must be considered. This list is long, but medication noncompliance and dietary indiscretion are the most common causes.

Symptoms and Prior History of HF

The classic symptoms for AHF include dyspnea at rest or exertion, and orthopnea, both of which unfortunately have poor sensitivity and specificity for AHF. As an isolated symptom, dyspnea is of marginal diagnostic utility (sensitivity and specificity for an HF diagnosis is 56% and 53%, respectively), and orthopnea is only slightly better (sensitivity and specificity 77% and 50%, respectively). A prior HF diagnosis makes repeat presentations much more likely (sensitivity and specificity 60% and 90%, respectively).17

Physical Examination

Simple observation and a directed examination can rapidly point to the diagnosis (Figure 2).

Electrocardiography

Because CAD is one of the most common underlying AHF etiologies, an electrocardiogram (ECG) should always be obtained early for a patient presenting with potential AHF. Although the ECG does not usually contribute to ED management, the identification of new ST-segment changes or a malignant arrhythmia will guide critical management decisions.

Imaging Studies

Chest X-ray Imaging. A chest X-ray (CXR) study must be considered early when a patient presents with signs and symptoms suggestive of AHF. Although the classic findings of HF (eg, Kerley B lines [short horizontal lines perpendicular to the pleural surface],18 interstitial congestion, pulmonary effusion) can lag behind the clinical presentation, and also be nondiagnostic in the setting of mild HF, the CXR is an effective aid in identifying other causes of dyspnea such as pneumonia. Ultimately, the utility of the CXR for diagnosis is similar to that of the history and physical examination in that it will be diagnostic when positive but cannot exclude AHF if normal.

Ultrasound. Because it is fast, inexpensive, noninvasive, and readily available in the ED, ultrasound is frequently used to evaluate potential HF patients. Several studies have demonstrated that the presence of B lines in two or more regions is specific for AHF (specificity 75%-100%), although the sensitivity may be limited (40%-91%).19-21 The presence of inferior vena cava (IVC) dilation is also associated with adverse outcomes.22 In 80 patients hospitalized with acute decompensated HF (ADHF), a dilated IVC (≥1.9 cm) at admission was associated with higher 90-day mortality (25.4% vs 3.4%, P = 0.009).23 These findings may be considered in groups: In an evaluation of the combination of LV EF, IVC collapsibility, and B lines for an HF diagnosis, the combination of all three had a poor sensitivity (36%) but an excellent specificity (100%), and any two of the three had a specificity of at least 93%.24

Laboratory Evaluation

Myocardial Strain: BNP/NTproBNP. Natriuretic peptides (NPs) are not AHF-specific, but rather they are synthesized and released by the myocardium in the setting of myocardial pressure or volume stress. They are manufactured as preproBNP, then enzymatically cleaved into the active BNP and the inactive fragment N-terminal proBNP (NTproBNP). The predominant hormonal effects of BNP are vasodilation and natriuresis, as well as antagonism of the hormones associated with sodium retention (aldosterone) and vasoconstriction (endothelin, norepinephrine).

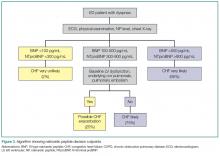

As AHF results in myocardial stress, NP elevation provides diagnostic and prognostic information. Clinical judgment supported by a BNP greater than 100 pg/mL is a better predictor of AHF than clinical judgment alone (accuracy 81% vs 74%, respectively).25 While low levels (BNP <100 pg/mL or NTproBNP <300 pg/mL) reliably exclude the diagnosis of HF (sensitivities >95%), higher levels (BNP >500 pg/mL, NTproBNP >900 pg/mL) are useful as “rule-in” markers, with specificity greater than 95%. The NTproBNP also requires adjustment for patients older than age 75 years, with a higher level (>1,800 pg/mL) to rule-in HF. The NP grey zone (BNP 100-500 pg/mL, NTproBNP 300-900 pg/mL)requires additional testing for accurate diagnoses (Figure 3).25-29

There are several confounders to the interpretation of NP results: NPs are negatively confounded by the presence of obesity, resulting in a lowering of the value as compared to the clinical presentation.Thus, the measured BNP level should be doubled if the patient’s body mass index exceeds 35 kg/m2.30 Secondly, because NP metabolism is partially renal dependent, elevated levels may not reflect AHF in the presence of renal failure. If the estimated glomerular filtration rate is less than 60 mL/min, measured BNP levels should be halved.31

AHF vs Myocardial Ischemia: Troponin Levels. Large registry data using contemporary troponin assays clearly identify the association between elevated troponin levels (>99th percentile in a healthy population) and increased short-term risk. With the US Food and Drug Association (FDA) approval of a high-sensitivity troponin (hs-cTnT) assay, a greater frequency of elevated cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and cardiac troponin I (cTnl) will be identified in AHF patients in the ED.

In one retrospective study of 4,705 AHF patients in the ED, hs-cTnT were elevated in 48.4% of cases (25.3% in cTnI, 37.9% in cTnT, and 82.2% in hs-cTnT). Although 1-year mortality was higher in those with elevated troponin (adjusted heart rate [HR] 1.61; CI 95% 1.38-1.88), elevated troponin was not associated with 30-day revisits to the ED (1.01; 0.87-1.19) and high sensitive elevations less than double the reference value had no impact on outcomes.32 Thus, in terms of management of AHF in the ED, slightly elevated stable serial troponins are more consistent with underlying HF, and should be managed as such. This is not true of rising/falling troponin levels, which should still engender concern for underlying myocardial ischemia and a different management pathway.

Renal function. Comprised renal function is an important predictor of AHF outcome. Large registry data from hospitalized HF patients demonstrate that a presenting blood urea nitrogen level greater than 43 mg/dL is one of the most important predictors of increased acute mortality,33 and levels below 30 mg/dL identify a cohort likely to be successfully managed in an observation environment.34 Creatinine is a helpful lagging indicator of mortality, with higher levels (>2.75 mg/dL) associated with increased short-term adverse outcomes and decreased therapeutic responsiveness (Figure 4).

For patients presenting with ADHF, a newer test recently approved by the FDA uses the product of the urine markers tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7, to generate a score predictive of acute kidney injury.35 While promising, no studies of ED outcomes are currently available.

Volume Assessment

Objective volume assessment is useful for diagnosis and prognosis in AHF. Bioimpedance vector analysis (BIVA) is a rapid, inexpensive, noninvasive technique that measures total body water by placing a pair of electrodes on the wrist and ipsilateral ankle. The BIVA measurements have strong correlations with the gold standard volume-assessment technique of deuterium dilution (r > 0.99).36 In HF, BIVA can assess volume depletion37 and overload,38 and identifies differences in hydration status between 90-day survivors and non-survivors (P < 0.01).39

Used in combination with BNP, one prospective study of 292 dyspneic patients found that, while BIVA was a strong predictor of AHF (c-statistic 0.93, P = 0.016), the most accurate volume status determination was the combination of both (c-statistic, 0.99; P = 0.005), for which the combined accuracy exceeded either alone.40 Finally, in 166 hospitalized HF patients discharged by BNP and BIVA parameters, vs 149 discharged based on clinical impressions, those assessed with BNP and BIVA had lower 6-month readmissions (23% vs 35%, P = 0.02) and overall cost of care.41

Combination Technologies

Obviously, EPs may consider multiple technologies to arrive at an accurate diagnosis. One prospective evaluation enrolled 236 patients to determine the diagnostic accuracy for AHF in the ED and reported lung ultrasound, CXR, and NTproBNP had a sensitivity of 57.7% and 88.0%, 74.5% and 86.3%, and a specificity of 97.6% and 28.0%. The best overall combination was the CXR with lung ultrasound (sensitivity 84.7%, specificity 77.7%).42

Another prospective study evaluated IVC diameter, bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), and NTproBNP in 96 elderly patients. ADHF patients had higher IVC diameters and lower collapsibility index, lower resistance and reactance, and higher NTproBNP levels. While all had high and statistically similar C-statistics (range 0.8 to 0.9) for an ADHF diagnosis, they concluded that IVC ultrasonography and BIA were as useful as NT-proBNP for diagnosing ADHF. 24

Diagnostic Scoring Systems

A scoring system has been proposed to improve diagnosis in the ED. Unfortunately, the value over clinical impression has not been clearly proven, though one randomized, controlled trial did not show statistically significant improvement in diagnostic accuracy when compared to standard care (77% vs 74%, P = 0.77).43

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for acute dyspnea is long and potentially arcane. Efforts should focus on excluding non-HF causes of dyspnea, while considering the high risk of alternative etiologies for signs and symptoms. These include asthma, COPD, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolism, which may represent the primary pathologies in a patient with a history of HF, or be the cause of a HF exacerbation. Additional causes of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema should also be considered (eg, acute respiratory distress syndrome, toxins, etc). Acute coronary syndrome and dyspnea may be angina equivalents—one important consideration.

Treatment and Management

Airway Management

Treatment of CH in the ED must always start with an immediate airway evaluation, with the possible need for endotracheal intubation preceding all diagnostic or other management considerations. Intubation is a decision most successfully based on physician clinical assessment, including oxygen (O2) selection rather than waiting for the results of objective measures such as arterial blood gas analysis.

Oxygen

Supplemental O2 should be administered to maintain an O2 saturation above 95%, but obviously is unnecessary in the absence of hypoxia.

Noninvasive Ventilation

Two kinds of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) are available, continuous positive airway pressure and bilevel positive airway pressure ventilation. The physiological differences between these types of NIV have little bearing on ED treatment.

Noninvasive ventilation has not been clearly shown to provide long-term mortality benefit. Large registry data44 report that outcomes are no worse than the alternative of endotracheal intubation, while multiple systematic reviews,45,46meta-analysis,47and Cochrane reviews48,49have established NIV as an acute pulmonary edema intervention that provides reductions in hospital mortality (numbers needed to treat [NNT] 13) and intubation (NNT 8), the prospective randomized C3PO (Congenital Cardiac Catheterization Project on Outcomes) trial50 failed to demonstrate any mortality reduction.

In patients with severe respiratory distress, NIV is a reasonable strategy during the aggressive administration of medical therapy in an attempt to avoid endotracheal intubation. However, NIV is not a stand-alone therapy and though its use may obviate the need for immediate intubation, its implementation should not be considered definitive management.

Correction of Abnormal Vital Signs: Abnormal SBP

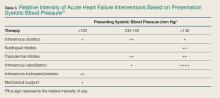

Vital signs are an important determinant of therapy, driving treatment strategies. Interventions for HF are based on the patient’s SBP, in particular correction of symptomatic hypotension and hypertensive HF (Table 3).51

Symptomatic Hypotension. The presence of symptomatic hypotension is an extremely poor prognostic finding in AHF. Inotrope therapy may be considered, but it does not reduce mortality except as a bridge to mechanical interventions (LV assist device or transplant).52-54 Temporary inotropic support is recommended for cardiogenic shock to maintain systemic perfusion and prevent end organ damage.3 The inotropic support includes administration of dopamine, dobutamine, or milrinone, though none have been proven to be superior over the other. The lowest possible dose of the selected inotrope should be used to limit arrhythmogenic effects. Inotropic agents should not be used in the absence of severe systolic dysfunction, or low BP, or impaired perfusion, or evidence of significantly decreased cardiac output.

Hypertensive Heart Failure. Defined as the rapid onset of pulmonary congestion with an SBP greater than 140 mm Hg, and commonly greater than 160 mm Hg, these patients may have profound dyspnea, requiring endotracheal intubation. However, in this situation, aggressive vasodilation is typically rapidly effective. Overall, patients presenting with an elevated SBP have lower rates of in-hospital mortality, 30-day myocardial infarction (MI), death, or rehospitalization, and a greater likelihood of discharge within 24 hours—as long as the elevated SBP is aggressively and rapidly treated.

Pharmacological Therapy

Pharmacological management is the mainstay for treating HF. No other acute therapy (eg, NIV) has demonstrated a morality benefit (See Table 4 for specific dose and administration strategies).55 The time to initiate pharmacological therapy and whether an aggressive approach is indicated must be based on the severity of the clinical symptoms and objective risk stratification measures (eg, NP, troponin levels).

Furosemide. Except for hypertensive HF—in which case BP lowering is the most important goal—diuretics are a mainstay of AHF treatment, and consensus guidelines provide a class I recommendation for their use.3 The DOSE (Diuretic Strategies in Patients with ADHF) trial56 prospectively evaluated diuretics in 308 hospitalized AHF patients and found no outcome differences in administration route (bolus or continuous infusion) or dose (high vs low dose). This study reported trends toward greater improvement with higher furosemide dosing, as well as greater diuresis, but at a cost of transient worsening of renal function.

In general, diuretics should be administered in an intravenous (IV) dose equal to 1 to 2.5 times the patient’s usual daily oral dose. For patients who are diuretic-naïve, a dose of 40 mg IV furosemide or 1 mg IV bumetanide, with subsequent dosing titrated to urine output, is recommended.

Vasodilators. In patients with both AHF and even mildly elevated BP, vasodilators can be extremely effective in achieving symptom improvement. The choice of vasodilator, and how aggressive to increase dosing, depends upon symptom severity. The purpose of vasodilators is to lower BP and therefore, should not be used in the setting of hypotension or signs of hypoperfusion. Flow-limiting, preload-dependent CV states (eg, right ventricular infarction) increase the risk of hypotension, and are relative contraindications to the use of vasodilators. For patients who are severely dyspneic and with critical presentations, the emergency physician (EP) should preclude a detailed history and examination to initiate immediate therapy with short-acting agents that can be terminated rapidly in the case of an adverse event (eg, unexpected hypotension) are preferred.

Nitroglycerin. Nitroglycerin is the vasodilation agent of choice for hypertensive AHF. It is a short-acting, rapid-onset, venous and arterial dilator that decreases BP by preload reduction, and by afterload reduction in higher doses. Nitroglycerin has coronary vasodilatory effects associated with decreased ischemia, but should be avoided in patients taking phosphodiesterase inhibitors.55 Its most common side effect is headache, and hypotension occurs in about 3.5% of patients.57

Commonly given as a continuous infusion at IV doses up to 400 mcg/min, nitroglycerin may be associated with higher costs and longer LOS.58 Some authors suggest that bolus nitroglycerin therapy may be superior: In a retrospective study of 395 patients, an IV bolus of nitroglycerin 0.5 mg was superior to both an infusion, or a combination of bolus and infusion, as demonstrated by lower rates of ICU admission (48% vs 67% and 79%, respectively, P = 0.006) and shorter hospital stays (4.4 vs 6.3 and 7.3 days, respectively, P = 0.01). In all cohorts, adverse event rates were similar for hypotension, troponin elevation, and creatinine increase over 48 hours.59 Nitroprusside. Nitroprusside is a potent arterial and venous dilator that causes rapid decrease in BP and LV-filling pressures. It is usually considered more effective than nitroglycerin, despite a small study showing similar hemodynamic responses.60

Initial dosing of nitroprusside starts at 0.3 µg/kg/min IV, and is increased every 5 minutes to a maximum of 10 mcg/kg/min, based on BP and clinical response. The most common acute complication of nitroprusside infusions is hypotension. Cyanide toxicity may occur with prolonged use, high doses, or in patients with renal failure.55

Nesiritide. Exogenously administered, the B-type NP nesiritide is effective in lowering BP and improving dyspnea in AHF,55 although large prospective studies showed it had little long-term advantage over standard care.61 In a small, randomized, controlled trial, nesiritide reduced 30-day revisit LOS when given in an OU.62 The 22-minute half-life of nesiritide is longer than that of the nitrates, and its side effect is predominately hypotension, which occurs at rates similar to those of other vasodilators.55

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. Because angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) have chronic mortality reduction benefits, their use in the acute setting is theoretically attractive, however, this has been poorly proven in AHF ED patients. In a retrospective review of 103 patients with elevated NTproBNP levels receiving bolus IV enalaprilat within 3 hours of presentation, the mean SBP decreased by 30 mm Hg, with only 2% of patients developing hypotension.63 However, with the longer half-life of ACEIs, if hypotension occurs, the potential for a prolonged BP-lowering effect exists.

Calcium Channel Blockers. Clevidipine and nicardipine are rapidly acting IV calcium channel blockers that lower BP by selective arteriolar vasodilation and increased cardiac output as vascular resistance declines.55 Because these agents have no negative inotropic or chronotropic effects, they may be beneficial in hypertensive AHF. In an open-label trial of 104 hypertensive AHF patients, clevidipine was more effective than standard care for the rapid control of BP and relief of dyspnea.64

Morphine. Large registry analyses have demonstrated potential harm with the routine use of morphine,65 as do recent propensity score matched analyses.66 Until there are studies demonstrating benefit, the use of morphine at present should be reserved for palliative care.

Time to Treatment

Although a randomized controlled trial on the importance of time to treatment of AHF is unlikely to ever be completed, data suggest that, as in the case of MI, delayed AHF therapy is associated with adverse outcomes. In a study of 499 suspected AHF patients transferred by ambulance, patients randomized to immediate therapy vs those whose therapy was not initiated until hospital arrival (mean delay of 36 minutes), had a 251% increase in survival (P < 0.01).67

Furthermore, the delayed administration of vasoactive agents, defined as medication administered to alter hemodynamics (eg, dobutamine, dopamine, nitroglycerin, nesiritide) is also associated with harm,68 and registry studies demonstrate increased death rates (n = 35,700).69 Finally, another registry (n = 14,900) study demonstrated early IV furosemide is associated with decreased mortality.70 This latter finding was also validated in a prospective observational cohort study (mortality 2.3 vs 6.0 in early vs delayed therapy groups, respectively).71

Patient Disposition

One of the unique features of emergency medicine is the need to determine, with very limited information and time, a patient’s very short-term clinical trajectory. Few physicians are required to have greater accuracy with less information or time than do EPs. Several studies report objective data points and risk scores to assist in this task, but none has been universally adopted, reflecting the challenge of applying population data to individuals.

Short-term Prognosis

In 1,638 patients evaluated for 14-day outcomes, an HR lower than 50% maximal HR (MHR), and an SBP greater than 140 mm Hg were associated with the lowest rate of serious adverse events (SAEs) (6%) and hospitalization (38%).72 An MHR over 75% was associated with the highest SAE rate, although SAEs decreased as SBP increased (30%, 24%, and 21% with SBPs < 120 mm Hg, 120-140 mm Hg, and > 140 mm Hg, respectively).72

Risk Scores

In a prospective, observational cohort study of 1,100 ED patients, the Ottawa Heart Failure Risk Scale, combined with NTproBNP values, had a sensitivity of 95.8%—at the cost of increasing the admission rate (from 60.8% to 88%)—for serious adverse events (defined as death within 30 days), admission to a monitored unit, intubation, NIV, MI, or relapse resulting in hospital admission within 14 days.73

Observation Unit

Overall, 44% of in-patient HF admissions are for less than 3 days (Table 1),2 supporting the practice of managing selected patients in shorter clinical-care environments than in inpatient units. Further, ED patients presenting with moderate dyspnea require both a diagnosis and an evaluation of their therapeutic response to determine the need for hospitalization. However, evaluating therapeutic response requires more time than is available in the typical ED. Thus, an ED OU offers the following:

(1) The OU provides the EP with a longer evaluation time, and therefore a more accurate disposition may be effected;

(2) Costs are significantly lower in patients managed in an ED OU; and

(3) Patient satisfaction may be improved, as most patients prefer home management over hospitalization.

All three of these opportunities are supported by a number of studies,74-78 with validated entry and exclusion criteria, treatment algorithms and discharge metrics. Most recently, in a registry of hospitals in Spain registry, patients presenting to hospitals that had OUs had a 2.2-day shorter LOS, lower 30-day ED revisit rate, and similar mortality rates compared to those in institutions without OUs—although these beneficial effects occurred at the cost of an 8.9% higher admission rate.79

Patient Education

Intuitively, it would be expected that patient education would reduce return visits, 30-day hospitalizations, and AHF-related mortality. Unfortunately, it has not been demonstrated that patient education results in a consistent benefit at hospital discharge, or in the outpatient environment.80-85

Although AHF education in the ED has been poorly studied, areas that have shown promise are education occurring before ED management (ie, in the ED waiting area) in underinsured patients,86 and during ED care for patients with poor health care literacy.87 As educational interventions are both inexpensive and unlikely to result in harm, their implementation should be considered.

Conclusion

The spectrum of HF is a common presentation in the ED. Because HF generally appears as dyspnea, in a cohort with multiple comorbidities, the diagnosis can be challenging. This is complicated by the fact that patients with severe presentations may require life-saving interventions long before a clinical evaluation is completed (or even initiated). The skill of the EP, and his or her ability to improve the clinical condition before intubation is required, will determine the patient’s trajectory. Conversely, as a chronic condition, HF may present with moderate symptoms for which a short diuretic “tune-up” in an observation environment may be appropriate.

How these decisions are made will depend upon the local environment, the availability of outpatient resources, and individual patient choices. There are few chronic diseases that are more complex, are seen more often in the ED, or that require more skill and finesse in management.

1. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-e603.

2. Fitch KV, Engel T, Lauet J. The cost burden of worsening heart failure in the Medicare fee for service population: an actuarial analysis. Milliman Web site. 2017. http://www.milliman.com/insight/2017/The-cost-burden-of-worsening-heart-failure-in-the-Medicare-fee-for-service-population-An-actuarial-analysis/ Published April 3, 2017. Accessed June 1, 2017.

3. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147-e239. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019.

4. Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998-2008. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1669-1678. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1474.

5. Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Stroke Council. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606-619. doi:10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a.

6. Dunlay SM, Shah ND, Shi Q, et al. Lifetime costs of medical care after heart failure diagnosis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(1):68-75. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957225.

7. HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS); 2014 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). HCUPnet Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. http://bit.ly/2u2ymFA. Published 2014. Accessed July 27, 2017.

8. FY 2017 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables. CMS 2014 data based on DRGs, Table 5:List of MS-DRGs, Relative Weighting Factors and Geometric and Arithmetic Mean Length of Stay. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2017-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2017-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html. Published 2017. Accessed August 28, 2017.

9. Hospital Adjusted Expenses per Inpatient Day by Ownership. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://www.kff.org/health-costs/state-indicator/expenses-per-inpatient-day-by-ownership/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed August 2, 2017

10. Ellison, A. Average cost per inpatient day across 50 states. Becker’s Hospital CFO Report. http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/average-cost-per-inpatient-day-across-50-states-2016.html. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed August 2, 2017

11. Claret PG, Calder LA, Stiell IG, et al. Rates and predictive factors of return to the emergency department following an initial release by the emergency department for acute heart failure. [published online ahead of print April 3, 2017]. CJEM. 1-8. doi:10.1017/cem.2017.14.

12. Yam FK, Lew T, Eraly SA, Lin HW, Hirsch JD, Devor M. Changes in medication regimen complexity and the risk for 90-day hospital readmission and/or emergency department visits in U.S. Veterans with heart failure. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12(5):713-721. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.10.004.

13. Readmissions Reduction Program. CMS. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html Updated April 18, 2016. Accessed July 13, 2017.

14. Nowak RM, Reed BP, DiSomma S, et al. Presenting phenotypes of acute heart failure patients in the ED: Identification and implications. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(4):536-542. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.12.003.

15. Bennett SJ, Huster GA, Baker SL, et al. Characterization of the precipitants of hospitalization for heart failure decompensation. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7(3):168-174.

16. Kuo DC, Peacock WF. Diagnosing and managing acute heart failure in the emergency department. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2015;2(3):141-149. eCollection 2015 Sep. doi:10.15441/ceem.15.007.

17. Wang CS, FitzGerald JM, Schulzer M, Mak E, Ayas NT. Does this dyspneic patient in the emergency department have congestive heart failure? JAMA. 2005;294:1944-1956.

18. Koga T, Fujimoto K. Images in clinical medicine. Kerley’s A, B, and C line. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1539. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm0708489.

19. Glöckner E, Christ M, Geier F, et al. Accuracy of point-of-care B-Line lung ultrasound in comparison to NT-ProBNP for screening acute heart failure. Ultrasound Int Open. 2016;2(3):e90-e92. doi:10.1055/s-0042-108343.

20. Bitar Z, Maadarani O, Almerri K. Sonographic chest B-lines anticipate elevated B-type natriuretic peptide level, irrespective of ejection fraction. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5(1): 56. doi:10.1186/s13613-015-0100-x.

21. Miglioranza MH, Gargani L, Sant’Anna RT, et al. Lung ultrasound for the evaluation of pulmonary congestion in outpatients: a comparison with clinical assessment, natriuretic peptides, and echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(11):1141-1151. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.08.004.

22. Anderson KL, Jenq KY, Fields JM, Panebianco NL, Dean AJ. Diagnosing heart failure among acutely dyspneic patients with cardiac, inferior vena cava, and lung ultrasonography. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(8):1208-1214. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.05.007.

23. Cubo-Romano P, Torres-Macho J, Soni NJ, et al. Admission inferior vena cava measurements are associated with mortality after hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):778-784. doi:10.1002/jhm.2620.

24. Martínez PG, Martínez DM, García JC, Loidi JC. Amino-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide, inferior vena cava ultrasound, and bioelectrical impedance analysis for the diagnosis of acute decompensated CHF. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(9): 1817–1822. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.06.043.

25. Maisel AS, Krishnaswamy P, Nowak RM, et al; Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study Investigators. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(3):161-167.

26. Van Kimmenade RR, Pinto YM, Bayes-Genis A, Lainchbury JG, Richards AM, Januzzi JL Jr. Usefulness of intermediate amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide concentrations for diagnosis and prognosis of acute heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(3):386-390.

27. Moe GW, Howlett J, Januzzi JL, Zowall H; Canadian Multicenter Improved Management of Patients With Congestive Heart Failure (IMPROVE-CHF) Study Investigators. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide testing improves the management of patients with suspected acute heart failure: primary results of the Canadian prospective randomized multicenter IMPROVE-CHF study. Circulation. 2007;115(24):3103-3110.

28. Mayo DD, Colletti JE, Kuo DC. Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) testing in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2006;31(2):201-210.

29. Mueller C, Scholer A, Laule-Kilian K, et al. Use of B-type natriuretic peptide in the evaluation and management of acute dyspnea. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(7):647-654.

30. Krauser DG, Lloyd-Jones DM, Chae CU, et al. Effect of body mass index on natriuretic peptide levels in patients with acute congestive heart failure: a ProBNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department (PRIDE) substudy. Am Heart J. 2005;149(4):744-750.

31. McCullough PA, Duc P, Omland T, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide and renal function in the diagnosis of heart failure: an analysis from the Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(3):571-579.

32. Jacob J, Roset A, Miró Ò, et al; ICA-SEMES Research Group. EAHFE - TROPICA2 study. Prognostic value of troponin in patients with acute heart failure treated in Spanish hospital emergency departments. Biomarkers. 2017;22(3-4):337-344. doi:10.1080/1354750X.2016.1265006.

33. Fonarow GC, Adams KF Jr, Abraham WT, et al; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee, Study Group, and Investigators. Risk stratification for in-hospital mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure: classification and regression tree analysis. JAMA. 2005;293(5):572-580.

34. Burkhardt J, Peacock WF, Emerman CL. Predictors of emergency department observation unit outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(9):869-874.

35. Schanz M, Shi J, Wasser C, Alscher MD, Kimmel M. Urinary [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] for risk prediction of acute kidney injury in decompensated heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(7):485-491. doi:10.1002/clc.22683.

36. Kushner RF, Schoeller DA, Fjeld CR, Danford L: Is the impedance index (ht2/R) significant in predicting total body water? Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56(5): 835-839.

37. Ackland GL, Singh-Ranger D, Fox S, et al. Assessment of preoperative fluid depletion using bioimpedance analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92(1): 134-136.

38. Uszko-Lencer NH, Bothmer F, van Pol PE, Schols AM. Measuring body composition in chronic heart failure: a comparison of methods. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8(2): 208-214.

39. Santarelli S, Russo V, Lalle I, et al; GREAT network. Usefulness of combining admission brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) plus hospital discharge bioelectrical impedance vector analysis (BIVA) in predicting 90 days cardiovascular mortality in patients with acute heart failure. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12(4):445-451. doi:10.1007/s11739-016-1581-9.

40. Parrinello G, Paterna S, Di Pasquale P, et al. The usefulness of bioelectrical impedance analysis in differentiating dyspnea due to decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008;14(8): 676-686. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.04.005.

41. Valle R, Aspromonte N, Carbonieri E, et al. Fall in readmission rate for heart failure after implementation of B-type natriuretic peptide testing for discharge decision: a retrospective study. Int J Cardiol. 2008;126(3): 400-406.

42. Sartini S, Frizzi J, Borselli M, et al. Which method is best for an early accurate diagnosis of acute heart failure? Comparison between lung ultrasound, chest X-ray and NT pro-BNP performance: a prospective study. [published online ahead of print July 11, 2016]. Intern Emerg Med. doi:10.1007/s11739-016-1498-3.

43. Steinhart BD, Levy P, Vandenberghe H, et al. A randomized control trial using a validated prediction model for diagnosing acute heart failure in undifferentiated dyspneic emergency department patients-results of the GASP4Ar study. J Card Fail. 2017;23(2):145-152. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.08.007.

44. Tallman TA, Peacock WF, Emerman CL, et al; ADHERE Registry. Noninvasive ventilation outcomes in 2,430 acute decompensated heart failure patients: an ADHERE registry analysis. Acad EM. 2008;15(4):355–362. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00059.x.

45. Pang D, Keenan SP, Cook DJ, Sibbald WJ. The effect of positive pressure airway support on mortality and the need for intubation in cardiogenic pulmonary edema: a systematic review. Chest. 1998;114(4):1185-1192.

46. Peter JV, Moran JL, Phillips-Hughes J, Graham P, Bersten AD. Effect of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) on mortality in patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;367(9517):1155-1163.

47. Weng CL, Zhao YT, Liu QH, et al. Meta-analysis: Noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(9):590-600

48. Vital FM, Saconato H, Ladeira MT, et al. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (CPAP or bilevel NPPV) for cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD005351. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005351.pub2.

49. Vital FM, Ladeira MT, Atallah AN. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (CPAP or bilevel NPPV) for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD005351. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005351.pub3.

50. Gray A, Goodacre S, Seah M, Tilley S. Diuretic, opiate and nitrate use in severe acidotic acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema: analysis from the 3CPO trial. QJM. 2010;103(8):573-581. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcq077.

51. Collins SP, Storrow AB, Levy PD, et al. Early management of patients with acute heart failure: state of the art and future directions—a consensus document from the SAEM/HFSA acute heart failure working group. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(1):94-112. doi:10.1111/acem.12538.]

52. O’Connor CM, Gattis WA, Uretsky BF, et al. Continuous intravenous dobutamine is associated with an increased risk of death in patients with advanced heart failure: insights from the Flolan International Randomized Survival Trial (FIRST). Am Heart J. 1999;138(1 Pt 1):78-86.

53. Hershberger RE, Nauman D, Walker TL, Dutton D, Burgess D. Care processes and clinical outcomes of continuous outpatient support with inotropes (COSI) in patients with refractory endstage heart failure. J Card Fail. 2003;(9):180-187.

54. Gorodeski EZ, Chu EC, Reese JR, Shishehbor MH, Hsich E, Starling RC. Prognosis on chronic dobutamine or milrinone infusions for stage D heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(4):320-324. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.839076.

55. Collins SP, Levy PD, Martindale JL, et al. Clinical and research considerations for patients with hypertensive acute heart failure: A consensus statement from the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine and the Heart Failure Society of America Acute Heart Failure Working Group. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(8):922-931. doi:10.1111/acem.13025.

56. Felker GM, Lee KL, Bull DA, et al. Diuretic strategies in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364(9):797-805. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1005419.

57. Publication Committee for the VMAC Investigators (Vasodilatation in the Management of Acute CHF). Intravenous nesiritide vs nitroglycerin for treatment of decompensated congestive heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;287(12):1531-1540.

58. Gradman AH, Vekeman F, Eldar-Lissai A, Trahey A, Ong SH, Duh MS. Is addition of vasodilators to loop diuretics of value in the care of hospitalized acute heart failure patients? Real-world evidence from a retrospective analysis of a large United States hospital database. J Card Fail. 2014;20(11):853-863. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.08.006.

59. Wilson SS, Kwiatkowski GM, Millis SR, Purakal JD, Mahajan AP, Levy PD. Use of nitroglycerin by bolus prevents intensive care unit admission in patients with acute hypertensive heart failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(1):126-131. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.038.

60. Eryonucu B, Guler N, Guntekin U, Tuncer M. Comparison of the effects of nitroglycerin and nitroprusside on transmitral Doppler flow parameters in patients with hypertensive urgency. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(6):997–1001.

61. O’Connor CM, Starling RC, Hernandez AF, et al. Effect of nesiritide in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(1):32-43. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1100171.

62. Peacock WF 4th, Holland R, Gyarmathy R, et al. Observation unit treatment of heart failure with nesiritide: results from the proaction trial. J Emerg Med. 2005;29(3):243-252.

63. Ayaz SI, Sharkey CM, Kwiatkowski GM, et al. Intravenous enalaprilat for treatment of acute hypertensive heart failure in the emergency department. Int J Emerg Med. 2016;9(1):28. doi:10.1186/s12245-016-0125-4.

64. Peacock WF 4th, Chandra A, Char D, et al. Clevidipine in acute heart failure: results of the A study of BP control in acute heart failure-a pilot study (PRONTO). Am Heart J. 2014;167(4):529-536. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.12.023.

65. Peacock WF 4th, Hollander JE, Diercks DB, et al. Morphine and outcomes in acute decompensated heart failure: an ADHERE analysis. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(4):205-209. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.050419.

66. Miró Ò, Gil V, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Herrero-Puente P, Jet al; ICA-SEMES Research Group. Morphine use in the ED and outcomes of patients with acute heart failure: a propensity score-matching analysis based on the EAHFE registry. [published ahead of print April 12, 2017] Chest. pii:S0012-3692(17)30707-9. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.037.

67. Wuerz RC, Meador SA. Effects of prehospital medications on mortality and length of stay in congestive heart failure. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21(6):669-674.

68. Peacock WF 4th, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, Mills RM, Wynne J; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators; Adhere Study Group. Impact of early initiation of intravenous therapy for acute decompensated heart failure on outcomes in ADHERE. Cardiology. 2007; 107(1):44-51. doi:10.1159/000093612.

69. Peacock WF, Emerman C, Costanzo MR, Diercks DB, Lopatin M, Fonarow GC. Early vasoactive drugs improve heart failure outcomes. Congest Heart Fail. 2009;15(6): 256-264. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7133.2009.00112.x.

70. Maisel AS, Peacock WF, McMullin N, et al. Timing of immunoreactive B-type natriuretic peptide levels and treatment delay in acute decompensated heart failure: an ADHERE (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(7):534-540. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.010.

71. Matsue Y, Damman K, Voors AA, et al. Time-to-Furosemide Treatment and Mortality in Patients Hospitalized With Acute Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Jun 27;69(25):3042-3051. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.042.

72. Claret PG, Stiell IG, Yan JW, et al. Hemodynamic, management, and outcomes of patients admitted to emergency department with heart failure. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24(1):132.

73. Stiell IG, Perry JJ, Clement CM, et al. Prospective and explicit clinical validation of the Ottawa Heart Failure Risk Scale, with and without use of quantitative NT-proBNP. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(3):316-327. doi:10.1111/acem.13141.

74. Pang PS, Jesse R, Collins SP, Maisel A. Patients with acute heart failure in the emergency department: do they all need to be admitted? J Card Fail. 2012;18:900-903. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.10.014.

75. Peacock WF 4th, Young J, Collins S, Emerman C, Diercks D. Heart failure observation units: optimizing care. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(1):22-33.

76. Storrow AB, Collins SP, Lyons MS, Wagoner LE, Gibler WB, Lindsell CJ. Emergency department observation of heart failure: preliminary analysis of safety and cost. Congest Heart Fail. 2005;11(2):68-72.

77. Peacock WF 4th, Remer EE, Aponte J, Moffa DA, Emerman CE, Albert NM. Effective observation unit treatment of decompensated heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2002;8(2):68 -73.

78. Peacock WF 4th, Albert NM. Observation unit management of heart failure. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19(1):209-232.

79. Miró O, Carbajosa V, Peacock WF 4th, et al; ICA-SEMES group. The effect of a short-stay unit on hospital admission and length of stay in acute heart failure: REDUCE-AHF study. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;40:30-36. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2017.01.015.

80. Ekman I, Andersson B, Ehnfors M, Matejka G, Persson B, Fagerberg B. Feasibility of a nurse-monitored, outpatient-care programme for elderly patients with moderate-to-severe, chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1998;19(8):1254-1260.

81. Riegel B, Carlson B, Kopp Z, LePetri B, Glaser D, Unger A. Effect of a standardized nurse case-management telephone intervention on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(6):705-712.

82. Laramee AS, Levinsky SK, Sargent J, Ross R, Callas P. Case management in a heterogeneous congestive heart failure population: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(7):809-817.

83. Stewart S, Pearson S, Horowitz JD. Effects of a home-based intervention among patients with congestive heart failure discharged from acute hospital care. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(10):1067-1072.

84. Stewart S, Marley JE, Horowitz JD. Effects of a multidisciplinary, home-based intervention on unplanned readmissions and survival among patients with chronic congestive heart failure: a randomised controlled study. Lancet. 1999;354(9184):1077-1083.

85. Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on primary care and hospital readmission. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(22):1441-1447.

86. Asthana V, Sundararajan M, Karun V, et al. Educational strategy for management of heart failure markedly reduces 90-day emergency department and hospital readmissions in un- and underinsured patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11Suppl): 780. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(17)34169-4.

87. Bell SP, Schnipper JL, Goggins K, et al; Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease (PILL-CVD) Study Group. Effect of pharmacist counseling intervention on health care utilization following hospital discharge: a randomized control trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):470-477. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3596-3.

Patients with heart failure (HF) present daily to busy EDs. An estimated 6.5 million Americans are living with this diagnosis, and the number is predicted to grow to 8 million by 2023.1 Most HF patients (82.1%) who present to EDs are hospitalized, while a selected minority are either managed in the ED and discharged (11.6%) or managed in observation units (OU) (6.3%).2 The prognosis after HF is initially diagnosed is poor, with a 5-year mortality of 50%,3 and after a single HF hospitalization, 29% will die within 1 year.4

One-third of the total Medicare budget is spent on HF, despite the fact that HF represents only 10.5% of the Medicare population.2 Up to 80% of HF costs are for hospitalizations, which cost an average of $11,840 per inpatient admission.5,6 The high costs are due to an average length of stay (LOS) of 5.2 days7 (Table 1).

Adding to hospital costs is the degree of “reactivism,” with approximately 20% of patients discharged from the ED returning within 2 weeks, of whom nearly 50% will be hospitalized.11 Following HF hospitalization and discharge, the 30-day readmission rate is 26.2%,2 increasing to 36% by 90 days.12 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has incentivized hospitals and providers to reduce admissions, but penalize hospitals that do not. Overall, CMS will reduce payments by up to 3% to hospitals with excess readmissions for select conditions, including HF.13

Causes of Heart Failure

Heart failure represents a final common pathway, which in the United States is most often due to coronary artery disease (CAD). Many types of pathology ultimately result in left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and much of its rising prevalence is a result of the success we now have in managing historically fatal cardiovascular (CV) conditions. These include hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), CAD, and valvular and other CV structural conditions.

Heart failure is caused by either a dilated ventricle with a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and inability to eject volume, or a stiffened ventricle with a preserved EF (HFpEF) that is unable to receive increased venous return. Both conditions acutely decompensate pulmonary congestion. A preserved EF is defined as an EF at or greater than 50%, whereas a reduced EF is at or less than 40%, with the 41% to 49% range considered as borderline preserved EF.3

While there are important differences in the treatment of chronic and subacute HF, driven by the EF, the effect of EF on early decision-making and treatment in the ED is negligible: Although the probability of HFpEF increases with increasing initial ED systolic blood pressure (SBP), clinical presentation and treatment in the ED are initially identical—regardless of the EF.

Noninvasive continuous transcutaneous hemodynamic monitoring is available for ED use, and may provide further insight into the underlying pathophysiology. A study of 127 acute heart failure (AHF) ED patients identified three hemodynamic AHF phenotypes. These include normal cardiac index (CI) and systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI), low CI and SVRI, and low CI and elevated SVRI.14 While it is attractive to suggest therapeutic interventions based on these measurements, outcome data are lacking.

Presentation

The most common ED presentation of patients suffering from AHF is dyspnea secondary to volume overload, or as the result of acute hypertension with relatively less volume overload. However, regardless of the cause of dyspnea, it is not only the most common resulting complaint, but one that requires immediate treatment. Ultimately, 59% of all HF admissions are attributed to volume overload and dyspnea (Figure 1).15

Heart failure can also present in a more protean manner, with cough, fatigue, and edema, as well as more subtle symptoms predominating and resulting in a complicated differential diagnosis (Table 2).16

Because HF is a disease that most significantly affects older patients who frequently have concomitant morbidities (eg, myocardial ischemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] exacerbation, uncontrolled DM), other less clinically obvious disease presentations may actually be the cause of the AHF exacerbation.

Diagnosis

A focused history and physical examination that is part of all ED evaluations should be expedited whenever there is evidence of hemodynamic instability or respiratory compromise. An early working diagnosis is essential to avoid a delay in appropriate treatment, which is associated with increased mortality.

When HF is likely, the potential etiology and precipitants for decompensation must be considered. This list is long, but medication noncompliance and dietary indiscretion are the most common causes.

Symptoms and Prior History of HF

The classic symptoms for AHF include dyspnea at rest or exertion, and orthopnea, both of which unfortunately have poor sensitivity and specificity for AHF. As an isolated symptom, dyspnea is of marginal diagnostic utility (sensitivity and specificity for an HF diagnosis is 56% and 53%, respectively), and orthopnea is only slightly better (sensitivity and specificity 77% and 50%, respectively). A prior HF diagnosis makes repeat presentations much more likely (sensitivity and specificity 60% and 90%, respectively).17

Physical Examination

Simple observation and a directed examination can rapidly point to the diagnosis (Figure 2).

Electrocardiography

Because CAD is one of the most common underlying AHF etiologies, an electrocardiogram (ECG) should always be obtained early for a patient presenting with potential AHF. Although the ECG does not usually contribute to ED management, the identification of new ST-segment changes or a malignant arrhythmia will guide critical management decisions.

Imaging Studies

Chest X-ray Imaging. A chest X-ray (CXR) study must be considered early when a patient presents with signs and symptoms suggestive of AHF. Although the classic findings of HF (eg, Kerley B lines [short horizontal lines perpendicular to the pleural surface],18 interstitial congestion, pulmonary effusion) can lag behind the clinical presentation, and also be nondiagnostic in the setting of mild HF, the CXR is an effective aid in identifying other causes of dyspnea such as pneumonia. Ultimately, the utility of the CXR for diagnosis is similar to that of the history and physical examination in that it will be diagnostic when positive but cannot exclude AHF if normal.

Ultrasound. Because it is fast, inexpensive, noninvasive, and readily available in the ED, ultrasound is frequently used to evaluate potential HF patients. Several studies have demonstrated that the presence of B lines in two or more regions is specific for AHF (specificity 75%-100%), although the sensitivity may be limited (40%-91%).19-21 The presence of inferior vena cava (IVC) dilation is also associated with adverse outcomes.22 In 80 patients hospitalized with acute decompensated HF (ADHF), a dilated IVC (≥1.9 cm) at admission was associated with higher 90-day mortality (25.4% vs 3.4%, P = 0.009).23 These findings may be considered in groups: In an evaluation of the combination of LV EF, IVC collapsibility, and B lines for an HF diagnosis, the combination of all three had a poor sensitivity (36%) but an excellent specificity (100%), and any two of the three had a specificity of at least 93%.24

Laboratory Evaluation

Myocardial Strain: BNP/NTproBNP. Natriuretic peptides (NPs) are not AHF-specific, but rather they are synthesized and released by the myocardium in the setting of myocardial pressure or volume stress. They are manufactured as preproBNP, then enzymatically cleaved into the active BNP and the inactive fragment N-terminal proBNP (NTproBNP). The predominant hormonal effects of BNP are vasodilation and natriuresis, as well as antagonism of the hormones associated with sodium retention (aldosterone) and vasoconstriction (endothelin, norepinephrine).

As AHF results in myocardial stress, NP elevation provides diagnostic and prognostic information. Clinical judgment supported by a BNP greater than 100 pg/mL is a better predictor of AHF than clinical judgment alone (accuracy 81% vs 74%, respectively).25 While low levels (BNP <100 pg/mL or NTproBNP <300 pg/mL) reliably exclude the diagnosis of HF (sensitivities >95%), higher levels (BNP >500 pg/mL, NTproBNP >900 pg/mL) are useful as “rule-in” markers, with specificity greater than 95%. The NTproBNP also requires adjustment for patients older than age 75 years, with a higher level (>1,800 pg/mL) to rule-in HF. The NP grey zone (BNP 100-500 pg/mL, NTproBNP 300-900 pg/mL)requires additional testing for accurate diagnoses (Figure 3).25-29

There are several confounders to the interpretation of NP results: NPs are negatively confounded by the presence of obesity, resulting in a lowering of the value as compared to the clinical presentation.Thus, the measured BNP level should be doubled if the patient’s body mass index exceeds 35 kg/m2.30 Secondly, because NP metabolism is partially renal dependent, elevated levels may not reflect AHF in the presence of renal failure. If the estimated glomerular filtration rate is less than 60 mL/min, measured BNP levels should be halved.31

AHF vs Myocardial Ischemia: Troponin Levels. Large registry data using contemporary troponin assays clearly identify the association between elevated troponin levels (>99th percentile in a healthy population) and increased short-term risk. With the US Food and Drug Association (FDA) approval of a high-sensitivity troponin (hs-cTnT) assay, a greater frequency of elevated cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and cardiac troponin I (cTnl) will be identified in AHF patients in the ED.

In one retrospective study of 4,705 AHF patients in the ED, hs-cTnT were elevated in 48.4% of cases (25.3% in cTnI, 37.9% in cTnT, and 82.2% in hs-cTnT). Although 1-year mortality was higher in those with elevated troponin (adjusted heart rate [HR] 1.61; CI 95% 1.38-1.88), elevated troponin was not associated with 30-day revisits to the ED (1.01; 0.87-1.19) and high sensitive elevations less than double the reference value had no impact on outcomes.32 Thus, in terms of management of AHF in the ED, slightly elevated stable serial troponins are more consistent with underlying HF, and should be managed as such. This is not true of rising/falling troponin levels, which should still engender concern for underlying myocardial ischemia and a different management pathway.

Renal function. Comprised renal function is an important predictor of AHF outcome. Large registry data from hospitalized HF patients demonstrate that a presenting blood urea nitrogen level greater than 43 mg/dL is one of the most important predictors of increased acute mortality,33 and levels below 30 mg/dL identify a cohort likely to be successfully managed in an observation environment.34 Creatinine is a helpful lagging indicator of mortality, with higher levels (>2.75 mg/dL) associated with increased short-term adverse outcomes and decreased therapeutic responsiveness (Figure 4).

For patients presenting with ADHF, a newer test recently approved by the FDA uses the product of the urine markers tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7, to generate a score predictive of acute kidney injury.35 While promising, no studies of ED outcomes are currently available.

Volume Assessment

Objective volume assessment is useful for diagnosis and prognosis in AHF. Bioimpedance vector analysis (BIVA) is a rapid, inexpensive, noninvasive technique that measures total body water by placing a pair of electrodes on the wrist and ipsilateral ankle. The BIVA measurements have strong correlations with the gold standard volume-assessment technique of deuterium dilution (r > 0.99).36 In HF, BIVA can assess volume depletion37 and overload,38 and identifies differences in hydration status between 90-day survivors and non-survivors (P < 0.01).39

Used in combination with BNP, one prospective study of 292 dyspneic patients found that, while BIVA was a strong predictor of AHF (c-statistic 0.93, P = 0.016), the most accurate volume status determination was the combination of both (c-statistic, 0.99; P = 0.005), for which the combined accuracy exceeded either alone.40 Finally, in 166 hospitalized HF patients discharged by BNP and BIVA parameters, vs 149 discharged based on clinical impressions, those assessed with BNP and BIVA had lower 6-month readmissions (23% vs 35%, P = 0.02) and overall cost of care.41

Combination Technologies

Obviously, EPs may consider multiple technologies to arrive at an accurate diagnosis. One prospective evaluation enrolled 236 patients to determine the diagnostic accuracy for AHF in the ED and reported lung ultrasound, CXR, and NTproBNP had a sensitivity of 57.7% and 88.0%, 74.5% and 86.3%, and a specificity of 97.6% and 28.0%. The best overall combination was the CXR with lung ultrasound (sensitivity 84.7%, specificity 77.7%).42

Another prospective study evaluated IVC diameter, bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), and NTproBNP in 96 elderly patients. ADHF patients had higher IVC diameters and lower collapsibility index, lower resistance and reactance, and higher NTproBNP levels. While all had high and statistically similar C-statistics (range 0.8 to 0.9) for an ADHF diagnosis, they concluded that IVC ultrasonography and BIA were as useful as NT-proBNP for diagnosing ADHF. 24

Diagnostic Scoring Systems

A scoring system has been proposed to improve diagnosis in the ED. Unfortunately, the value over clinical impression has not been clearly proven, though one randomized, controlled trial did not show statistically significant improvement in diagnostic accuracy when compared to standard care (77% vs 74%, P = 0.77).43

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for acute dyspnea is long and potentially arcane. Efforts should focus on excluding non-HF causes of dyspnea, while considering the high risk of alternative etiologies for signs and symptoms. These include asthma, COPD, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolism, which may represent the primary pathologies in a patient with a history of HF, or be the cause of a HF exacerbation. Additional causes of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema should also be considered (eg, acute respiratory distress syndrome, toxins, etc). Acute coronary syndrome and dyspnea may be angina equivalents—one important consideration.

Treatment and Management

Airway Management

Treatment of CH in the ED must always start with an immediate airway evaluation, with the possible need for endotracheal intubation preceding all diagnostic or other management considerations. Intubation is a decision most successfully based on physician clinical assessment, including oxygen (O2) selection rather than waiting for the results of objective measures such as arterial blood gas analysis.

Oxygen

Supplemental O2 should be administered to maintain an O2 saturation above 95%, but obviously is unnecessary in the absence of hypoxia.

Noninvasive Ventilation

Two kinds of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) are available, continuous positive airway pressure and bilevel positive airway pressure ventilation. The physiological differences between these types of NIV have little bearing on ED treatment.

Noninvasive ventilation has not been clearly shown to provide long-term mortality benefit. Large registry data44 report that outcomes are no worse than the alternative of endotracheal intubation, while multiple systematic reviews,45,46meta-analysis,47and Cochrane reviews48,49have established NIV as an acute pulmonary edema intervention that provides reductions in hospital mortality (numbers needed to treat [NNT] 13) and intubation (NNT 8), the prospective randomized C3PO (Congenital Cardiac Catheterization Project on Outcomes) trial50 failed to demonstrate any mortality reduction.

In patients with severe respiratory distress, NIV is a reasonable strategy during the aggressive administration of medical therapy in an attempt to avoid endotracheal intubation. However, NIV is not a stand-alone therapy and though its use may obviate the need for immediate intubation, its implementation should not be considered definitive management.

Correction of Abnormal Vital Signs: Abnormal SBP

Vital signs are an important determinant of therapy, driving treatment strategies. Interventions for HF are based on the patient’s SBP, in particular correction of symptomatic hypotension and hypertensive HF (Table 3).51

Symptomatic Hypotension. The presence of symptomatic hypotension is an extremely poor prognostic finding in AHF. Inotrope therapy may be considered, but it does not reduce mortality except as a bridge to mechanical interventions (LV assist device or transplant).52-54 Temporary inotropic support is recommended for cardiogenic shock to maintain systemic perfusion and prevent end organ damage.3 The inotropic support includes administration of dopamine, dobutamine, or milrinone, though none have been proven to be superior over the other. The lowest possible dose of the selected inotrope should be used to limit arrhythmogenic effects. Inotropic agents should not be used in the absence of severe systolic dysfunction, or low BP, or impaired perfusion, or evidence of significantly decreased cardiac output.

Hypertensive Heart Failure. Defined as the rapid onset of pulmonary congestion with an SBP greater than 140 mm Hg, and commonly greater than 160 mm Hg, these patients may have profound dyspnea, requiring endotracheal intubation. However, in this situation, aggressive vasodilation is typically rapidly effective. Overall, patients presenting with an elevated SBP have lower rates of in-hospital mortality, 30-day myocardial infarction (MI), death, or rehospitalization, and a greater likelihood of discharge within 24 hours—as long as the elevated SBP is aggressively and rapidly treated.

Pharmacological Therapy

Pharmacological management is the mainstay for treating HF. No other acute therapy (eg, NIV) has demonstrated a morality benefit (See Table 4 for specific dose and administration strategies).55 The time to initiate pharmacological therapy and whether an aggressive approach is indicated must be based on the severity of the clinical symptoms and objective risk stratification measures (eg, NP, troponin levels).

Furosemide. Except for hypertensive HF—in which case BP lowering is the most important goal—diuretics are a mainstay of AHF treatment, and consensus guidelines provide a class I recommendation for their use.3 The DOSE (Diuretic Strategies in Patients with ADHF) trial56 prospectively evaluated diuretics in 308 hospitalized AHF patients and found no outcome differences in administration route (bolus or continuous infusion) or dose (high vs low dose). This study reported trends toward greater improvement with higher furosemide dosing, as well as greater diuresis, but at a cost of transient worsening of renal function.

In general, diuretics should be administered in an intravenous (IV) dose equal to 1 to 2.5 times the patient’s usual daily oral dose. For patients who are diuretic-naïve, a dose of 40 mg IV furosemide or 1 mg IV bumetanide, with subsequent dosing titrated to urine output, is recommended.

Vasodilators. In patients with both AHF and even mildly elevated BP, vasodilators can be extremely effective in achieving symptom improvement. The choice of vasodilator, and how aggressive to increase dosing, depends upon symptom severity. The purpose of vasodilators is to lower BP and therefore, should not be used in the setting of hypotension or signs of hypoperfusion. Flow-limiting, preload-dependent CV states (eg, right ventricular infarction) increase the risk of hypotension, and are relative contraindications to the use of vasodilators. For patients who are severely dyspneic and with critical presentations, the emergency physician (EP) should preclude a detailed history and examination to initiate immediate therapy with short-acting agents that can be terminated rapidly in the case of an adverse event (eg, unexpected hypotension) are preferred.

Nitroglycerin. Nitroglycerin is the vasodilation agent of choice for hypertensive AHF. It is a short-acting, rapid-onset, venous and arterial dilator that decreases BP by preload reduction, and by afterload reduction in higher doses. Nitroglycerin has coronary vasodilatory effects associated with decreased ischemia, but should be avoided in patients taking phosphodiesterase inhibitors.55 Its most common side effect is headache, and hypotension occurs in about 3.5% of patients.57

Commonly given as a continuous infusion at IV doses up to 400 mcg/min, nitroglycerin may be associated with higher costs and longer LOS.58 Some authors suggest that bolus nitroglycerin therapy may be superior: In a retrospective study of 395 patients, an IV bolus of nitroglycerin 0.5 mg was superior to both an infusion, or a combination of bolus and infusion, as demonstrated by lower rates of ICU admission (48% vs 67% and 79%, respectively, P = 0.006) and shorter hospital stays (4.4 vs 6.3 and 7.3 days, respectively, P = 0.01). In all cohorts, adverse event rates were similar for hypotension, troponin elevation, and creatinine increase over 48 hours.59 Nitroprusside. Nitroprusside is a potent arterial and venous dilator that causes rapid decrease in BP and LV-filling pressures. It is usually considered more effective than nitroglycerin, despite a small study showing similar hemodynamic responses.60

Initial dosing of nitroprusside starts at 0.3 µg/kg/min IV, and is increased every 5 minutes to a maximum of 10 mcg/kg/min, based on BP and clinical response. The most common acute complication of nitroprusside infusions is hypotension. Cyanide toxicity may occur with prolonged use, high doses, or in patients with renal failure.55

Nesiritide. Exogenously administered, the B-type NP nesiritide is effective in lowering BP and improving dyspnea in AHF,55 although large prospective studies showed it had little long-term advantage over standard care.61 In a small, randomized, controlled trial, nesiritide reduced 30-day revisit LOS when given in an OU.62 The 22-minute half-life of nesiritide is longer than that of the nitrates, and its side effect is predominately hypotension, which occurs at rates similar to those of other vasodilators.55

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. Because angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) have chronic mortality reduction benefits, their use in the acute setting is theoretically attractive, however, this has been poorly proven in AHF ED patients. In a retrospective review of 103 patients with elevated NTproBNP levels receiving bolus IV enalaprilat within 3 hours of presentation, the mean SBP decreased by 30 mm Hg, with only 2% of patients developing hypotension.63 However, with the longer half-life of ACEIs, if hypotension occurs, the potential for a prolonged BP-lowering effect exists.

Calcium Channel Blockers. Clevidipine and nicardipine are rapidly acting IV calcium channel blockers that lower BP by selective arteriolar vasodilation and increased cardiac output as vascular resistance declines.55 Because these agents have no negative inotropic or chronotropic effects, they may be beneficial in hypertensive AHF. In an open-label trial of 104 hypertensive AHF patients, clevidipine was more effective than standard care for the rapid control of BP and relief of dyspnea.64

Morphine. Large registry analyses have demonstrated potential harm with the routine use of morphine,65 as do recent propensity score matched analyses.66 Until there are studies demonstrating benefit, the use of morphine at present should be reserved for palliative care.

Time to Treatment

Although a randomized controlled trial on the importance of time to treatment of AHF is unlikely to ever be completed, data suggest that, as in the case of MI, delayed AHF therapy is associated with adverse outcomes. In a study of 499 suspected AHF patients transferred by ambulance, patients randomized to immediate therapy vs those whose therapy was not initiated until hospital arrival (mean delay of 36 minutes), had a 251% increase in survival (P < 0.01).67

Furthermore, the delayed administration of vasoactive agents, defined as medication administered to alter hemodynamics (eg, dobutamine, dopamine, nitroglycerin, nesiritide) is also associated with harm,68 and registry studies demonstrate increased death rates (n = 35,700).69 Finally, another registry (n = 14,900) study demonstrated early IV furosemide is associated with decreased mortality.70 This latter finding was also validated in a prospective observational cohort study (mortality 2.3 vs 6.0 in early vs delayed therapy groups, respectively).71

Patient Disposition

One of the unique features of emergency medicine is the need to determine, with very limited information and time, a patient’s very short-term clinical trajectory. Few physicians are required to have greater accuracy with less information or time than do EPs. Several studies report objective data points and risk scores to assist in this task, but none has been universally adopted, reflecting the challenge of applying population data to individuals.

Short-term Prognosis

In 1,638 patients evaluated for 14-day outcomes, an HR lower than 50% maximal HR (MHR), and an SBP greater than 140 mm Hg were associated with the lowest rate of serious adverse events (SAEs) (6%) and hospitalization (38%).72 An MHR over 75% was associated with the highest SAE rate, although SAEs decreased as SBP increased (30%, 24%, and 21% with SBPs < 120 mm Hg, 120-140 mm Hg, and > 140 mm Hg, respectively).72

Risk Scores

In a prospective, observational cohort study of 1,100 ED patients, the Ottawa Heart Failure Risk Scale, combined with NTproBNP values, had a sensitivity of 95.8%—at the cost of increasing the admission rate (from 60.8% to 88%)—for serious adverse events (defined as death within 30 days), admission to a monitored unit, intubation, NIV, MI, or relapse resulting in hospital admission within 14 days.73

Observation Unit

Overall, 44% of in-patient HF admissions are for less than 3 days (Table 1),2 supporting the practice of managing selected patients in shorter clinical-care environments than in inpatient units. Further, ED patients presenting with moderate dyspnea require both a diagnosis and an evaluation of their therapeutic response to determine the need for hospitalization. However, evaluating therapeutic response requires more time than is available in the typical ED. Thus, an ED OU offers the following:

(1) The OU provides the EP with a longer evaluation time, and therefore a more accurate disposition may be effected;

(2) Costs are significantly lower in patients managed in an ED OU; and

(3) Patient satisfaction may be improved, as most patients prefer home management over hospitalization.

All three of these opportunities are supported by a number of studies,74-78 with validated entry and exclusion criteria, treatment algorithms and discharge metrics. Most recently, in a registry of hospitals in Spain registry, patients presenting to hospitals that had OUs had a 2.2-day shorter LOS, lower 30-day ED revisit rate, and similar mortality rates compared to those in institutions without OUs—although these beneficial effects occurred at the cost of an 8.9% higher admission rate.79

Patient Education

Intuitively, it would be expected that patient education would reduce return visits, 30-day hospitalizations, and AHF-related mortality. Unfortunately, it has not been demonstrated that patient education results in a consistent benefit at hospital discharge, or in the outpatient environment.80-85

Although AHF education in the ED has been poorly studied, areas that have shown promise are education occurring before ED management (ie, in the ED waiting area) in underinsured patients,86 and during ED care for patients with poor health care literacy.87 As educational interventions are both inexpensive and unlikely to result in harm, their implementation should be considered.

Conclusion