User login

By the time a mortician in the northeast British town of Hyde, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom, noticed Dr. Harold Shipman’s patients were dying at an exorbitant rate, the doctor had probably killed close to 300 of them, according to Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine and author of “Demon Doctors: Physicians as Serial Killers.”

Shipman, labeled ‘‘the most prolific serial killer in the history of the United Kingdom—and probably the world,’’ was officially convicted of killing 15 patients in 2000 and sentenced to 15 consecutive life sentences.1 In January 2004 he was found hanged in his prison cell.

Sometimes referred to as caregiver-associated serial killings, these incidents generate profound shock in the healthcare community. As repellent and relatively rare as this behavior is, and as controversial as the topic is, neither individuals nor institutions can afford to disassociate themselves from the subject. Hospitalists should not hide from this issue and should not feel they will be accused of “treason” if they educate themselves and bring suspicious behavior to the awareness of superiors, says Beatrice Crofts Yorker, JD, RN, MS, FAAN, dean of the College of Health and Human Services at California State University, Los Angeles. On the contrary, she says, “first, do no harm” also entails ensuring everyone else around you follows the same ethic.

Dr. Yorker, who has been studying this phenomenon since 1986, published the first examination of cases of serial murder by nurses in the American Journal of Nursing (AJN) in 1988. “It is a serious problem that has been under-recognized, and it is the right thing to blow the whistle when adverse patient incidents are associated with the presence of a specific healthcare provider,” says Dr. Yorker. “In fact, most of the cases came to the attention of authorities because a nurse blew the whistle. The sad thing is that some of the nurses were disciplined for their protective actions; however, they were ultimately vindicated.”

A veteran of the phenomenon urges continued vigilance. “As a general caveat, there needs to be a higher index of suspicion for these incidents,” says Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH, the former head of the veterans healthcare system who had to deal with three incidents of serial murder at Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals in the 1990s. “These incidents are grossly underreported.”

Incidence and Cause of Death

Drs. Kizer and Yorker were two of the investigators who reviewed epidemiologic studies, toxicology evidence, and court transcripts for data on healthcare professionals prosecuted between 1970 and 2006.

“Dr. Robert Forrest, who was a forensic toxicologist getting a law degree and wrote his dissertation on the topic of serial murder by healthcare providers, contacted me after the AJN article came out,” says Dr. Yorker. Dr. Forrest has been the testifying expert in most of the U.K. cases. “After the Charles Cullen case hit the news, The New York Times and Modern Healthcare contacted me regarding my study in AJN and the Journal of Nursing Law. That is how Ken Kizer and Paula Lampe found me.” (Cullen, a registered nurse, received 11 consecutive life sentences in 2006 after pleading guilty to administering lethal doses of medication to more than 40 patients in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.)

Lampe, an author, had been studying cases in Europe. “Because both Robert and Paula provided additional data on some cases, they were co-authors—as was Ken—who provided data on the VA cases and an important public policy perspective,” says Dr. Yorker.

The search showed 90 criminal prosecutions of healthcare providers who met the criteria of serial murder of patients. Of those, 54 have been convicted—45 for serial murder, four for attempted murder, and five on lesser charges. Since the publication of their study, one more of the accused has received a sentence of life in prison, another has been convicted and sentenced to 20 years, one committed suicide in prison, and two additional nurses in Germany and the Czech Republic have been arrested and confessed to serial murder of patients. In addition, Dr. Yorker is continuing to follow two large-scale murder-for-profit prosecutions. There are four defendants in each case. Further, three individuals have been found liable for wrongful death in the amounts of $27 million, $8 million, and $450,000 in damages.

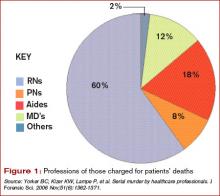

Injection was the main method used by healthcare killers, followed by suffocation, poisoning, and tampering with equipment. Prosecutions were reported in 20 countries, with 40% of the incidents taking place in the United States. Nursing personnel were 86% of the healthcare providers prosecuted; 12% were physicians, and 2% were allied health professionals. The number of patient deaths that resulted in a murder conviction is 317, and the number of suspicious patient deaths attributed to the 54 convicted caregivers is 2,113.

“Physicians as serial killers are remarkably uncommon,” says Dr. Iserson, who is also director of the Arizona Bioethics Program at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson. “Nurses [who are serial killers] are much more common, but of course there are more nurses in the hospital, just as there are ancillary people.” (See Figure 1, left.) Dr. Iserson, who practices emergency medicine and consults nationally on bioethics, advises maintaining caution when examining data of charges or suspicions that were never proved.

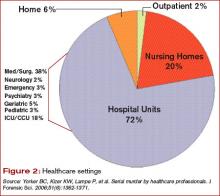

Most of these crimes (70%) occur in hospital units. (See Figure 2, left.) Victims are almost always female, as are almost half (49%) of convicted serial killers and 55% of the total number of prosecuted healthcare providers. Males are disproportionately represented among prosecuted nurses.

Motives: Who Is Always There?

Although the motives are complex, some common threads connect these crimes. “There are some classical signs, if you will,” says Dr. Kizer.

When the same person repeatedly calls a code and always seems to be in the thick of it, that is one prime indicator. These people are usually legitimately present in those settings and circumstances—for example, they are on call or working a shift—which makes it more difficult to discern when something is awry. Commonly, the perpetrators have easy access to high-alert drugs without sufficient accountability. Sometimes, once an investigation has been launched it is discovered the person has falsified his or her credentials.

In hospitals, experts say, the “rescuer” or “hero” personality is often on display in those who kill patients—the first person there to give the patient drugs or attempt to save the patient.

“What you are going to see as a pattern,” says Dr. Iserson, “is that they need to be near death.” Codes or calls for respiratory arrest are the most common; patients who have cardiac arrests are much harder to save. Being the hero is not always the motive; the converse can also apply.

Such is the case with nurse Orville Lynn Majors, LPN, convicted of six murders at the Vermillion county hospital in Clinton, Ind. The deaths were consistent with injections of potassium chloride and epinephrine according to prosecutors. Majors’ coworkers were concerned that patients were coding in alarming numbers while in his care. Although this information did not come out until after he was apprehended, his coworkers had a good idea which of his patients would not survive: Patients who were whiny, demanding, or required a lot of work. “The scuttlebutt or rumor among his coworkers,” says Dr. Kizer, “is that they could almost predict which patients would have a demise under his care.”

Although a typical profile of the serial healthcare murderer has been demonstrated in many cases, in many other cases the demographics and behaviors of these killers have deviated widely from generalized assumptions.2 Therefore, before looking at people, look at the numbers.

An unusual number of calls and codes may occur in a particular area of the hospital. “In ICUs you expect a lot of [codes and calls], but not on general post-op wards or the pediatrics MICU,” Dr. Kizer says. “When this happens in these settings it should raise a red flag.”

Unfortunately, most hospitals don’t track mortality on a monthly basis per unit or ward or ICU, so they may not recognize when something is out of line in a timely manner. Also, the hospital committee assigned to review deaths may be remiss in its duty to meet regularly or otherwise perform according to policy.

Another factor that should raise a red flag is a disproportionate number of codes or deaths on the same shift—most often the night shift. Often, someone says, “Gee, it seems like there’s an awful lot of codes lately,” explains Dr. Kizer. An unusually high rate of successful codes is another sign.

For example, in the 1995-1996 case of Kristen Gilbert, an RN convicted of four murders at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Northampton, Mass., she was having an extramarital affair with a hospital security guard who worked the evening shift. Protocol required that security be called to all cardiopulmonary arrests. Gilbert used stimulant epinephrine to make their hearts race out of control. The epidemiologic data later showed that suspicious codes occurred when both were on duty. “The patients always seemed to recover and she was the hero,” says Dr. Kizer. “She wanted to look good for her boyfriend.”

Similarly, Richard Angelo, a charge nurse at Good Samaritan Hospital in West Islip, Long Island, N.Y., admitted that between 1987 and 1989 he injected patients with paralyzing drugs Pavulon (pancuronium) and Anectine (succinylcholine). He wanted his colleagues to admire him for performing well in a code. During his confession, he likened himself to volunteer firefighters who set fires. In fact, Dr. Iserson makes this same parallel. “From what we can tell,” he says, “these people don’t really care whether the person dies or not. They would rather they not [die], so they can be seen as the hero. It’s all about them.” As with instances of arson, he says, the perpetrator is “the first one to show up at the fire watch, over and over again.”

Obstacles to Disclosure

Even when healthcare workers and related personnel come forward with their suspicions, law enforcement may be a barrier to prosecution.

In the United Kingdom, a Manchester mortician took her observations about the excessive deaths and cremations in Harold Shipman’s practice to her father and brother, who were also in the family business. She also obtained the support of a local female general practitioner. The two women went to the police, explaining that most patients who had died had not been critically ill and noted that the doctor had exhibited peculiar behavior when he was questioned.

But, says Dr. Iserson, the response again was typical: “‘Oh, foolish women. That can’t be happening.’ And it wasn’t until Shipman killed the wrong person [a former town mayor, mother of a prominent lawyer] that things started to unravel for him.” When police finally looked at other deaths Shipman had certified, a pattern emerged. He would overdose patients with diamorphine, sign their death certificates, then forge medical records to indicate they were in poor health.

A second common response by institutions is just as much of a barrier to bringing these crimes to light and ultimately, prosecution. “In essence,” says Dr. Iserson, “that response is, ‘Well, maybe it is happening but, boy, it sure is going to put our institution in a bad light. So let’s just not say anything.’ ”

This was the case with Michael Swango, a doctor who worked in several states and a number of countries. He was charged with five murders and may have been involved in 126 deaths. Swango confessed to the deaths that occurred in a Veterans Affairs hospital in Northport, N.Y., where he reportedly injected three veterans with a drug that stopped their hearts. He had forged “do not resuscitate” orders for the three. He was sentenced to two life sentences. It is possible that he killed as many as 35-60 people in the United States and Zimbabwe. But before it was all out in the open, “some very prominent people were involved in sweeping it under the rug,” says Dr. Iserson, “and they didn’t even get a slap on the wrist.”

Hiring Practices

One of the most shocking aspects of the Cullen case was that institutional coverup and employee privacy policies meant his prior employers never revealed the problems to prospective employers.

“Identifying potential serial killers is not at all the total problem,” says Dr. Iserson. “The problem is getting the powers that be to act. What they typically do is pass the problem on to somebody else, in effect, saying, ‘We don’t want you to work here anymore. We won’t necessarily write you a good letter of recommendation, but we will say that you worked here, and basically we just want you to go away.’ ”

An investigation revealed that Cullen had a history of reported incidents at hospitals in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, but there were no tracking or disclosure systems in place as he moved from one hospital to another. His employment history included termination from several hospitals because of misconduct, hospitalizations for mental illness, and a criminal investigation regarding improper medication administration.

In an open letter published in The New York Times on March 14, 2004, Somerset Medical Center (Somerville, N.J.) asserted: “Mr. Cullen worked at nine other healthcare facilities over a 16-year period. His former work history problems were not revealed to us. Nor were any state agencies or licensing boards able to provide us with accurate information about his employment history.”

Cullen had been investigated by three hospitals, a nursing home, and two prosecutors for suspicious patient deaths. He was fired by five hospitals and one nursing home for suspected wrongdoing. But Cullen continued to find employment and kill patients.

“Confidentiality is essential [as is] not leaking to the media, which can taint the investigation,” says Dr. Yorker. “The Charles Cullen case should motivate hospitalists to [participate in helping to stop the systemic mechanism that made possible] his killing over 40 patients in nine different hospitals and a nursing home before being stopped. This erodes the public trust in hospitals.”

The Health Care Quality Improvement Act provides some immunity for reporters of adverse information, but it applies only to physicians—not communications between employers.

The American Society for Healthcare Risk Management (ASHRM) and Dr. Kizer and his colleagues are in alignment in advocating for the provision of more comprehensive immunity to help healthcare employees and patients when they report these incidents.3

“If you have information that a worker is harming patients, the institution should be able to tell prospective employers and not worry about getting sued,” says Dr. Yorker. A number of states have passed varying forms of legislation so far, and ASHRM is recommending this be a federal matter. Dr. Kizer and his group recommend that reporting of suspected serial murderers should be considered for coverage under Good Samaritan laws.

Other Complicating Factors

Another problem in bringing legitimate cases to prosecution is when providers are accused on trumped-up charges, which in Dr. Iserson’s view amounts to prosecutorial malpractice. Examples are cases post-Hurricane Katrina, when physicians and nurses were charged with patient deaths.

Internationally, an example is the case in Libya where the main defendants—a Palestinian doctor and five Bulgarian nurses—were charged with injecting 426 children with HIV in 1998, causing an epidemic at El-Fath Children’s Hospital in Benghazi. According to World Politics Watch, dozens of foreign medical professionals were arrested, with six eventually charged and forced to confess by Libyan authorities. Subsequent research published in the journal Nature indicated that viral strains present in the infected children were present at the hospital before 1998.

“This was a case of political blackmail,” says Dr. Iserson. These cases may not be clear-cut and may be open to negative interpretations that “make people skittish. That is why institutions are prone to say, ‘Gee, maybe it’s just one of those kinds of cases. We don’t want to make that kind of mistake.’ ”

Also problematic is the variable rate at which hospitals perform autopsies.

“Autopsy rates are down in many communities to 1% or 2% or even lower,” says Dr. Kizer. “When the data point to the possibility of a crime on a particular unit, the site needs to be treated as a crime scene. In most hospitals, when someone dies, you get them off the floor and you clean up as quickly as possible. That shouldn’t be the case if it is a suspected crime scene. Ideally there should be standardized processes or protocols whenever there is suspicion. And those protocols may be different than when a patient ordinarily dies.”

Seeking Solutions

Hospitalists and other professionals—especially nurses and ancillary personnel—have an obligation to be informed and astute regarding individual characteristics and signs of suspicious patient deaths. Appropriate epidemiological, toxicological, and psychological data must be collected and analyzed routinely.

“Data about this phenomenon need to be disseminated to heighten awareness that serial murder of patients is a significant concern that extends beyond a few shocking, isolated incidents,” write Drs. Yorker and Kizer and their co-authors.

Institutional hiring practices must be changed so balance is achieved between preventing wrongful discharge or denial-of-employment lawsuits and protecting patient safety. Existing state legislation and future federal legislation for institutional immunity is an important element of patient advocacy that hospitalists can support.

Ultimately, hospitalists must be informed, aware, and alert. “Most [suspicions] will not be anything,” says Dr. Iserson. “Just pay attention to it.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Yorker BC, Kizer KW, Lampe P, et al. Serial murder by healthcare professionals. J Forensic Sci. 2006 Nov;51(6):1362-1371.

- Wolf BC, Lavezzi WA. Paths to destruction: the lives and crimes of two serial killers. J Forensic Sci. 2007 Jan;52(1):199-203.

- ASHRM. American Society for Healthcare Risk Management. A call for federal immunity to protect health care employers … and patients. Chicago: Monograph; April 1, 2005; www.ashrm.org/ashrm/resources/files/Monograph.Immunity.pdf.

By the time a mortician in the northeast British town of Hyde, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom, noticed Dr. Harold Shipman’s patients were dying at an exorbitant rate, the doctor had probably killed close to 300 of them, according to Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine and author of “Demon Doctors: Physicians as Serial Killers.”

Shipman, labeled ‘‘the most prolific serial killer in the history of the United Kingdom—and probably the world,’’ was officially convicted of killing 15 patients in 2000 and sentenced to 15 consecutive life sentences.1 In January 2004 he was found hanged in his prison cell.

Sometimes referred to as caregiver-associated serial killings, these incidents generate profound shock in the healthcare community. As repellent and relatively rare as this behavior is, and as controversial as the topic is, neither individuals nor institutions can afford to disassociate themselves from the subject. Hospitalists should not hide from this issue and should not feel they will be accused of “treason” if they educate themselves and bring suspicious behavior to the awareness of superiors, says Beatrice Crofts Yorker, JD, RN, MS, FAAN, dean of the College of Health and Human Services at California State University, Los Angeles. On the contrary, she says, “first, do no harm” also entails ensuring everyone else around you follows the same ethic.

Dr. Yorker, who has been studying this phenomenon since 1986, published the first examination of cases of serial murder by nurses in the American Journal of Nursing (AJN) in 1988. “It is a serious problem that has been under-recognized, and it is the right thing to blow the whistle when adverse patient incidents are associated with the presence of a specific healthcare provider,” says Dr. Yorker. “In fact, most of the cases came to the attention of authorities because a nurse blew the whistle. The sad thing is that some of the nurses were disciplined for their protective actions; however, they were ultimately vindicated.”

A veteran of the phenomenon urges continued vigilance. “As a general caveat, there needs to be a higher index of suspicion for these incidents,” says Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH, the former head of the veterans healthcare system who had to deal with three incidents of serial murder at Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals in the 1990s. “These incidents are grossly underreported.”

Incidence and Cause of Death

Drs. Kizer and Yorker were two of the investigators who reviewed epidemiologic studies, toxicology evidence, and court transcripts for data on healthcare professionals prosecuted between 1970 and 2006.

“Dr. Robert Forrest, who was a forensic toxicologist getting a law degree and wrote his dissertation on the topic of serial murder by healthcare providers, contacted me after the AJN article came out,” says Dr. Yorker. Dr. Forrest has been the testifying expert in most of the U.K. cases. “After the Charles Cullen case hit the news, The New York Times and Modern Healthcare contacted me regarding my study in AJN and the Journal of Nursing Law. That is how Ken Kizer and Paula Lampe found me.” (Cullen, a registered nurse, received 11 consecutive life sentences in 2006 after pleading guilty to administering lethal doses of medication to more than 40 patients in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.)

Lampe, an author, had been studying cases in Europe. “Because both Robert and Paula provided additional data on some cases, they were co-authors—as was Ken—who provided data on the VA cases and an important public policy perspective,” says Dr. Yorker.

The search showed 90 criminal prosecutions of healthcare providers who met the criteria of serial murder of patients. Of those, 54 have been convicted—45 for serial murder, four for attempted murder, and five on lesser charges. Since the publication of their study, one more of the accused has received a sentence of life in prison, another has been convicted and sentenced to 20 years, one committed suicide in prison, and two additional nurses in Germany and the Czech Republic have been arrested and confessed to serial murder of patients. In addition, Dr. Yorker is continuing to follow two large-scale murder-for-profit prosecutions. There are four defendants in each case. Further, three individuals have been found liable for wrongful death in the amounts of $27 million, $8 million, and $450,000 in damages.

Injection was the main method used by healthcare killers, followed by suffocation, poisoning, and tampering with equipment. Prosecutions were reported in 20 countries, with 40% of the incidents taking place in the United States. Nursing personnel were 86% of the healthcare providers prosecuted; 12% were physicians, and 2% were allied health professionals. The number of patient deaths that resulted in a murder conviction is 317, and the number of suspicious patient deaths attributed to the 54 convicted caregivers is 2,113.

“Physicians as serial killers are remarkably uncommon,” says Dr. Iserson, who is also director of the Arizona Bioethics Program at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson. “Nurses [who are serial killers] are much more common, but of course there are more nurses in the hospital, just as there are ancillary people.” (See Figure 1, left.) Dr. Iserson, who practices emergency medicine and consults nationally on bioethics, advises maintaining caution when examining data of charges or suspicions that were never proved.

Most of these crimes (70%) occur in hospital units. (See Figure 2, left.) Victims are almost always female, as are almost half (49%) of convicted serial killers and 55% of the total number of prosecuted healthcare providers. Males are disproportionately represented among prosecuted nurses.

Motives: Who Is Always There?

Although the motives are complex, some common threads connect these crimes. “There are some classical signs, if you will,” says Dr. Kizer.

When the same person repeatedly calls a code and always seems to be in the thick of it, that is one prime indicator. These people are usually legitimately present in those settings and circumstances—for example, they are on call or working a shift—which makes it more difficult to discern when something is awry. Commonly, the perpetrators have easy access to high-alert drugs without sufficient accountability. Sometimes, once an investigation has been launched it is discovered the person has falsified his or her credentials.

In hospitals, experts say, the “rescuer” or “hero” personality is often on display in those who kill patients—the first person there to give the patient drugs or attempt to save the patient.

“What you are going to see as a pattern,” says Dr. Iserson, “is that they need to be near death.” Codes or calls for respiratory arrest are the most common; patients who have cardiac arrests are much harder to save. Being the hero is not always the motive; the converse can also apply.

Such is the case with nurse Orville Lynn Majors, LPN, convicted of six murders at the Vermillion county hospital in Clinton, Ind. The deaths were consistent with injections of potassium chloride and epinephrine according to prosecutors. Majors’ coworkers were concerned that patients were coding in alarming numbers while in his care. Although this information did not come out until after he was apprehended, his coworkers had a good idea which of his patients would not survive: Patients who were whiny, demanding, or required a lot of work. “The scuttlebutt or rumor among his coworkers,” says Dr. Kizer, “is that they could almost predict which patients would have a demise under his care.”

Although a typical profile of the serial healthcare murderer has been demonstrated in many cases, in many other cases the demographics and behaviors of these killers have deviated widely from generalized assumptions.2 Therefore, before looking at people, look at the numbers.

An unusual number of calls and codes may occur in a particular area of the hospital. “In ICUs you expect a lot of [codes and calls], but not on general post-op wards or the pediatrics MICU,” Dr. Kizer says. “When this happens in these settings it should raise a red flag.”

Unfortunately, most hospitals don’t track mortality on a monthly basis per unit or ward or ICU, so they may not recognize when something is out of line in a timely manner. Also, the hospital committee assigned to review deaths may be remiss in its duty to meet regularly or otherwise perform according to policy.

Another factor that should raise a red flag is a disproportionate number of codes or deaths on the same shift—most often the night shift. Often, someone says, “Gee, it seems like there’s an awful lot of codes lately,” explains Dr. Kizer. An unusually high rate of successful codes is another sign.

For example, in the 1995-1996 case of Kristen Gilbert, an RN convicted of four murders at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Northampton, Mass., she was having an extramarital affair with a hospital security guard who worked the evening shift. Protocol required that security be called to all cardiopulmonary arrests. Gilbert used stimulant epinephrine to make their hearts race out of control. The epidemiologic data later showed that suspicious codes occurred when both were on duty. “The patients always seemed to recover and she was the hero,” says Dr. Kizer. “She wanted to look good for her boyfriend.”

Similarly, Richard Angelo, a charge nurse at Good Samaritan Hospital in West Islip, Long Island, N.Y., admitted that between 1987 and 1989 he injected patients with paralyzing drugs Pavulon (pancuronium) and Anectine (succinylcholine). He wanted his colleagues to admire him for performing well in a code. During his confession, he likened himself to volunteer firefighters who set fires. In fact, Dr. Iserson makes this same parallel. “From what we can tell,” he says, “these people don’t really care whether the person dies or not. They would rather they not [die], so they can be seen as the hero. It’s all about them.” As with instances of arson, he says, the perpetrator is “the first one to show up at the fire watch, over and over again.”

Obstacles to Disclosure

Even when healthcare workers and related personnel come forward with their suspicions, law enforcement may be a barrier to prosecution.

In the United Kingdom, a Manchester mortician took her observations about the excessive deaths and cremations in Harold Shipman’s practice to her father and brother, who were also in the family business. She also obtained the support of a local female general practitioner. The two women went to the police, explaining that most patients who had died had not been critically ill and noted that the doctor had exhibited peculiar behavior when he was questioned.

But, says Dr. Iserson, the response again was typical: “‘Oh, foolish women. That can’t be happening.’ And it wasn’t until Shipman killed the wrong person [a former town mayor, mother of a prominent lawyer] that things started to unravel for him.” When police finally looked at other deaths Shipman had certified, a pattern emerged. He would overdose patients with diamorphine, sign their death certificates, then forge medical records to indicate they were in poor health.

A second common response by institutions is just as much of a barrier to bringing these crimes to light and ultimately, prosecution. “In essence,” says Dr. Iserson, “that response is, ‘Well, maybe it is happening but, boy, it sure is going to put our institution in a bad light. So let’s just not say anything.’ ”

This was the case with Michael Swango, a doctor who worked in several states and a number of countries. He was charged with five murders and may have been involved in 126 deaths. Swango confessed to the deaths that occurred in a Veterans Affairs hospital in Northport, N.Y., where he reportedly injected three veterans with a drug that stopped their hearts. He had forged “do not resuscitate” orders for the three. He was sentenced to two life sentences. It is possible that he killed as many as 35-60 people in the United States and Zimbabwe. But before it was all out in the open, “some very prominent people were involved in sweeping it under the rug,” says Dr. Iserson, “and they didn’t even get a slap on the wrist.”

Hiring Practices

One of the most shocking aspects of the Cullen case was that institutional coverup and employee privacy policies meant his prior employers never revealed the problems to prospective employers.

“Identifying potential serial killers is not at all the total problem,” says Dr. Iserson. “The problem is getting the powers that be to act. What they typically do is pass the problem on to somebody else, in effect, saying, ‘We don’t want you to work here anymore. We won’t necessarily write you a good letter of recommendation, but we will say that you worked here, and basically we just want you to go away.’ ”

An investigation revealed that Cullen had a history of reported incidents at hospitals in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, but there were no tracking or disclosure systems in place as he moved from one hospital to another. His employment history included termination from several hospitals because of misconduct, hospitalizations for mental illness, and a criminal investigation regarding improper medication administration.

In an open letter published in The New York Times on March 14, 2004, Somerset Medical Center (Somerville, N.J.) asserted: “Mr. Cullen worked at nine other healthcare facilities over a 16-year period. His former work history problems were not revealed to us. Nor were any state agencies or licensing boards able to provide us with accurate information about his employment history.”

Cullen had been investigated by three hospitals, a nursing home, and two prosecutors for suspicious patient deaths. He was fired by five hospitals and one nursing home for suspected wrongdoing. But Cullen continued to find employment and kill patients.

“Confidentiality is essential [as is] not leaking to the media, which can taint the investigation,” says Dr. Yorker. “The Charles Cullen case should motivate hospitalists to [participate in helping to stop the systemic mechanism that made possible] his killing over 40 patients in nine different hospitals and a nursing home before being stopped. This erodes the public trust in hospitals.”

The Health Care Quality Improvement Act provides some immunity for reporters of adverse information, but it applies only to physicians—not communications between employers.

The American Society for Healthcare Risk Management (ASHRM) and Dr. Kizer and his colleagues are in alignment in advocating for the provision of more comprehensive immunity to help healthcare employees and patients when they report these incidents.3

“If you have information that a worker is harming patients, the institution should be able to tell prospective employers and not worry about getting sued,” says Dr. Yorker. A number of states have passed varying forms of legislation so far, and ASHRM is recommending this be a federal matter. Dr. Kizer and his group recommend that reporting of suspected serial murderers should be considered for coverage under Good Samaritan laws.

Other Complicating Factors

Another problem in bringing legitimate cases to prosecution is when providers are accused on trumped-up charges, which in Dr. Iserson’s view amounts to prosecutorial malpractice. Examples are cases post-Hurricane Katrina, when physicians and nurses were charged with patient deaths.

Internationally, an example is the case in Libya where the main defendants—a Palestinian doctor and five Bulgarian nurses—were charged with injecting 426 children with HIV in 1998, causing an epidemic at El-Fath Children’s Hospital in Benghazi. According to World Politics Watch, dozens of foreign medical professionals were arrested, with six eventually charged and forced to confess by Libyan authorities. Subsequent research published in the journal Nature indicated that viral strains present in the infected children were present at the hospital before 1998.

“This was a case of political blackmail,” says Dr. Iserson. These cases may not be clear-cut and may be open to negative interpretations that “make people skittish. That is why institutions are prone to say, ‘Gee, maybe it’s just one of those kinds of cases. We don’t want to make that kind of mistake.’ ”

Also problematic is the variable rate at which hospitals perform autopsies.

“Autopsy rates are down in many communities to 1% or 2% or even lower,” says Dr. Kizer. “When the data point to the possibility of a crime on a particular unit, the site needs to be treated as a crime scene. In most hospitals, when someone dies, you get them off the floor and you clean up as quickly as possible. That shouldn’t be the case if it is a suspected crime scene. Ideally there should be standardized processes or protocols whenever there is suspicion. And those protocols may be different than when a patient ordinarily dies.”

Seeking Solutions

Hospitalists and other professionals—especially nurses and ancillary personnel—have an obligation to be informed and astute regarding individual characteristics and signs of suspicious patient deaths. Appropriate epidemiological, toxicological, and psychological data must be collected and analyzed routinely.

“Data about this phenomenon need to be disseminated to heighten awareness that serial murder of patients is a significant concern that extends beyond a few shocking, isolated incidents,” write Drs. Yorker and Kizer and their co-authors.

Institutional hiring practices must be changed so balance is achieved between preventing wrongful discharge or denial-of-employment lawsuits and protecting patient safety. Existing state legislation and future federal legislation for institutional immunity is an important element of patient advocacy that hospitalists can support.

Ultimately, hospitalists must be informed, aware, and alert. “Most [suspicions] will not be anything,” says Dr. Iserson. “Just pay attention to it.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Yorker BC, Kizer KW, Lampe P, et al. Serial murder by healthcare professionals. J Forensic Sci. 2006 Nov;51(6):1362-1371.

- Wolf BC, Lavezzi WA. Paths to destruction: the lives and crimes of two serial killers. J Forensic Sci. 2007 Jan;52(1):199-203.

- ASHRM. American Society for Healthcare Risk Management. A call for federal immunity to protect health care employers … and patients. Chicago: Monograph; April 1, 2005; www.ashrm.org/ashrm/resources/files/Monograph.Immunity.pdf.

By the time a mortician in the northeast British town of Hyde, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom, noticed Dr. Harold Shipman’s patients were dying at an exorbitant rate, the doctor had probably killed close to 300 of them, according to Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine and author of “Demon Doctors: Physicians as Serial Killers.”

Shipman, labeled ‘‘the most prolific serial killer in the history of the United Kingdom—and probably the world,’’ was officially convicted of killing 15 patients in 2000 and sentenced to 15 consecutive life sentences.1 In January 2004 he was found hanged in his prison cell.

Sometimes referred to as caregiver-associated serial killings, these incidents generate profound shock in the healthcare community. As repellent and relatively rare as this behavior is, and as controversial as the topic is, neither individuals nor institutions can afford to disassociate themselves from the subject. Hospitalists should not hide from this issue and should not feel they will be accused of “treason” if they educate themselves and bring suspicious behavior to the awareness of superiors, says Beatrice Crofts Yorker, JD, RN, MS, FAAN, dean of the College of Health and Human Services at California State University, Los Angeles. On the contrary, she says, “first, do no harm” also entails ensuring everyone else around you follows the same ethic.

Dr. Yorker, who has been studying this phenomenon since 1986, published the first examination of cases of serial murder by nurses in the American Journal of Nursing (AJN) in 1988. “It is a serious problem that has been under-recognized, and it is the right thing to blow the whistle when adverse patient incidents are associated with the presence of a specific healthcare provider,” says Dr. Yorker. “In fact, most of the cases came to the attention of authorities because a nurse blew the whistle. The sad thing is that some of the nurses were disciplined for their protective actions; however, they were ultimately vindicated.”

A veteran of the phenomenon urges continued vigilance. “As a general caveat, there needs to be a higher index of suspicion for these incidents,” says Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH, the former head of the veterans healthcare system who had to deal with three incidents of serial murder at Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals in the 1990s. “These incidents are grossly underreported.”

Incidence and Cause of Death

Drs. Kizer and Yorker were two of the investigators who reviewed epidemiologic studies, toxicology evidence, and court transcripts for data on healthcare professionals prosecuted between 1970 and 2006.

“Dr. Robert Forrest, who was a forensic toxicologist getting a law degree and wrote his dissertation on the topic of serial murder by healthcare providers, contacted me after the AJN article came out,” says Dr. Yorker. Dr. Forrest has been the testifying expert in most of the U.K. cases. “After the Charles Cullen case hit the news, The New York Times and Modern Healthcare contacted me regarding my study in AJN and the Journal of Nursing Law. That is how Ken Kizer and Paula Lampe found me.” (Cullen, a registered nurse, received 11 consecutive life sentences in 2006 after pleading guilty to administering lethal doses of medication to more than 40 patients in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.)

Lampe, an author, had been studying cases in Europe. “Because both Robert and Paula provided additional data on some cases, they were co-authors—as was Ken—who provided data on the VA cases and an important public policy perspective,” says Dr. Yorker.

The search showed 90 criminal prosecutions of healthcare providers who met the criteria of serial murder of patients. Of those, 54 have been convicted—45 for serial murder, four for attempted murder, and five on lesser charges. Since the publication of their study, one more of the accused has received a sentence of life in prison, another has been convicted and sentenced to 20 years, one committed suicide in prison, and two additional nurses in Germany and the Czech Republic have been arrested and confessed to serial murder of patients. In addition, Dr. Yorker is continuing to follow two large-scale murder-for-profit prosecutions. There are four defendants in each case. Further, three individuals have been found liable for wrongful death in the amounts of $27 million, $8 million, and $450,000 in damages.

Injection was the main method used by healthcare killers, followed by suffocation, poisoning, and tampering with equipment. Prosecutions were reported in 20 countries, with 40% of the incidents taking place in the United States. Nursing personnel were 86% of the healthcare providers prosecuted; 12% were physicians, and 2% were allied health professionals. The number of patient deaths that resulted in a murder conviction is 317, and the number of suspicious patient deaths attributed to the 54 convicted caregivers is 2,113.

“Physicians as serial killers are remarkably uncommon,” says Dr. Iserson, who is also director of the Arizona Bioethics Program at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson. “Nurses [who are serial killers] are much more common, but of course there are more nurses in the hospital, just as there are ancillary people.” (See Figure 1, left.) Dr. Iserson, who practices emergency medicine and consults nationally on bioethics, advises maintaining caution when examining data of charges or suspicions that were never proved.

Most of these crimes (70%) occur in hospital units. (See Figure 2, left.) Victims are almost always female, as are almost half (49%) of convicted serial killers and 55% of the total number of prosecuted healthcare providers. Males are disproportionately represented among prosecuted nurses.

Motives: Who Is Always There?

Although the motives are complex, some common threads connect these crimes. “There are some classical signs, if you will,” says Dr. Kizer.

When the same person repeatedly calls a code and always seems to be in the thick of it, that is one prime indicator. These people are usually legitimately present in those settings and circumstances—for example, they are on call or working a shift—which makes it more difficult to discern when something is awry. Commonly, the perpetrators have easy access to high-alert drugs without sufficient accountability. Sometimes, once an investigation has been launched it is discovered the person has falsified his or her credentials.

In hospitals, experts say, the “rescuer” or “hero” personality is often on display in those who kill patients—the first person there to give the patient drugs or attempt to save the patient.

“What you are going to see as a pattern,” says Dr. Iserson, “is that they need to be near death.” Codes or calls for respiratory arrest are the most common; patients who have cardiac arrests are much harder to save. Being the hero is not always the motive; the converse can also apply.

Such is the case with nurse Orville Lynn Majors, LPN, convicted of six murders at the Vermillion county hospital in Clinton, Ind. The deaths were consistent with injections of potassium chloride and epinephrine according to prosecutors. Majors’ coworkers were concerned that patients were coding in alarming numbers while in his care. Although this information did not come out until after he was apprehended, his coworkers had a good idea which of his patients would not survive: Patients who were whiny, demanding, or required a lot of work. “The scuttlebutt or rumor among his coworkers,” says Dr. Kizer, “is that they could almost predict which patients would have a demise under his care.”

Although a typical profile of the serial healthcare murderer has been demonstrated in many cases, in many other cases the demographics and behaviors of these killers have deviated widely from generalized assumptions.2 Therefore, before looking at people, look at the numbers.

An unusual number of calls and codes may occur in a particular area of the hospital. “In ICUs you expect a lot of [codes and calls], but not on general post-op wards or the pediatrics MICU,” Dr. Kizer says. “When this happens in these settings it should raise a red flag.”

Unfortunately, most hospitals don’t track mortality on a monthly basis per unit or ward or ICU, so they may not recognize when something is out of line in a timely manner. Also, the hospital committee assigned to review deaths may be remiss in its duty to meet regularly or otherwise perform according to policy.

Another factor that should raise a red flag is a disproportionate number of codes or deaths on the same shift—most often the night shift. Often, someone says, “Gee, it seems like there’s an awful lot of codes lately,” explains Dr. Kizer. An unusually high rate of successful codes is another sign.

For example, in the 1995-1996 case of Kristen Gilbert, an RN convicted of four murders at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Northampton, Mass., she was having an extramarital affair with a hospital security guard who worked the evening shift. Protocol required that security be called to all cardiopulmonary arrests. Gilbert used stimulant epinephrine to make their hearts race out of control. The epidemiologic data later showed that suspicious codes occurred when both were on duty. “The patients always seemed to recover and she was the hero,” says Dr. Kizer. “She wanted to look good for her boyfriend.”

Similarly, Richard Angelo, a charge nurse at Good Samaritan Hospital in West Islip, Long Island, N.Y., admitted that between 1987 and 1989 he injected patients with paralyzing drugs Pavulon (pancuronium) and Anectine (succinylcholine). He wanted his colleagues to admire him for performing well in a code. During his confession, he likened himself to volunteer firefighters who set fires. In fact, Dr. Iserson makes this same parallel. “From what we can tell,” he says, “these people don’t really care whether the person dies or not. They would rather they not [die], so they can be seen as the hero. It’s all about them.” As with instances of arson, he says, the perpetrator is “the first one to show up at the fire watch, over and over again.”

Obstacles to Disclosure

Even when healthcare workers and related personnel come forward with their suspicions, law enforcement may be a barrier to prosecution.

In the United Kingdom, a Manchester mortician took her observations about the excessive deaths and cremations in Harold Shipman’s practice to her father and brother, who were also in the family business. She also obtained the support of a local female general practitioner. The two women went to the police, explaining that most patients who had died had not been critically ill and noted that the doctor had exhibited peculiar behavior when he was questioned.

But, says Dr. Iserson, the response again was typical: “‘Oh, foolish women. That can’t be happening.’ And it wasn’t until Shipman killed the wrong person [a former town mayor, mother of a prominent lawyer] that things started to unravel for him.” When police finally looked at other deaths Shipman had certified, a pattern emerged. He would overdose patients with diamorphine, sign their death certificates, then forge medical records to indicate they were in poor health.

A second common response by institutions is just as much of a barrier to bringing these crimes to light and ultimately, prosecution. “In essence,” says Dr. Iserson, “that response is, ‘Well, maybe it is happening but, boy, it sure is going to put our institution in a bad light. So let’s just not say anything.’ ”

This was the case with Michael Swango, a doctor who worked in several states and a number of countries. He was charged with five murders and may have been involved in 126 deaths. Swango confessed to the deaths that occurred in a Veterans Affairs hospital in Northport, N.Y., where he reportedly injected three veterans with a drug that stopped their hearts. He had forged “do not resuscitate” orders for the three. He was sentenced to two life sentences. It is possible that he killed as many as 35-60 people in the United States and Zimbabwe. But before it was all out in the open, “some very prominent people were involved in sweeping it under the rug,” says Dr. Iserson, “and they didn’t even get a slap on the wrist.”

Hiring Practices

One of the most shocking aspects of the Cullen case was that institutional coverup and employee privacy policies meant his prior employers never revealed the problems to prospective employers.

“Identifying potential serial killers is not at all the total problem,” says Dr. Iserson. “The problem is getting the powers that be to act. What they typically do is pass the problem on to somebody else, in effect, saying, ‘We don’t want you to work here anymore. We won’t necessarily write you a good letter of recommendation, but we will say that you worked here, and basically we just want you to go away.’ ”

An investigation revealed that Cullen had a history of reported incidents at hospitals in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, but there were no tracking or disclosure systems in place as he moved from one hospital to another. His employment history included termination from several hospitals because of misconduct, hospitalizations for mental illness, and a criminal investigation regarding improper medication administration.

In an open letter published in The New York Times on March 14, 2004, Somerset Medical Center (Somerville, N.J.) asserted: “Mr. Cullen worked at nine other healthcare facilities over a 16-year period. His former work history problems were not revealed to us. Nor were any state agencies or licensing boards able to provide us with accurate information about his employment history.”

Cullen had been investigated by three hospitals, a nursing home, and two prosecutors for suspicious patient deaths. He was fired by five hospitals and one nursing home for suspected wrongdoing. But Cullen continued to find employment and kill patients.

“Confidentiality is essential [as is] not leaking to the media, which can taint the investigation,” says Dr. Yorker. “The Charles Cullen case should motivate hospitalists to [participate in helping to stop the systemic mechanism that made possible] his killing over 40 patients in nine different hospitals and a nursing home before being stopped. This erodes the public trust in hospitals.”

The Health Care Quality Improvement Act provides some immunity for reporters of adverse information, but it applies only to physicians—not communications between employers.

The American Society for Healthcare Risk Management (ASHRM) and Dr. Kizer and his colleagues are in alignment in advocating for the provision of more comprehensive immunity to help healthcare employees and patients when they report these incidents.3

“If you have information that a worker is harming patients, the institution should be able to tell prospective employers and not worry about getting sued,” says Dr. Yorker. A number of states have passed varying forms of legislation so far, and ASHRM is recommending this be a federal matter. Dr. Kizer and his group recommend that reporting of suspected serial murderers should be considered for coverage under Good Samaritan laws.

Other Complicating Factors

Another problem in bringing legitimate cases to prosecution is when providers are accused on trumped-up charges, which in Dr. Iserson’s view amounts to prosecutorial malpractice. Examples are cases post-Hurricane Katrina, when physicians and nurses were charged with patient deaths.

Internationally, an example is the case in Libya where the main defendants—a Palestinian doctor and five Bulgarian nurses—were charged with injecting 426 children with HIV in 1998, causing an epidemic at El-Fath Children’s Hospital in Benghazi. According to World Politics Watch, dozens of foreign medical professionals were arrested, with six eventually charged and forced to confess by Libyan authorities. Subsequent research published in the journal Nature indicated that viral strains present in the infected children were present at the hospital before 1998.

“This was a case of political blackmail,” says Dr. Iserson. These cases may not be clear-cut and may be open to negative interpretations that “make people skittish. That is why institutions are prone to say, ‘Gee, maybe it’s just one of those kinds of cases. We don’t want to make that kind of mistake.’ ”

Also problematic is the variable rate at which hospitals perform autopsies.

“Autopsy rates are down in many communities to 1% or 2% or even lower,” says Dr. Kizer. “When the data point to the possibility of a crime on a particular unit, the site needs to be treated as a crime scene. In most hospitals, when someone dies, you get them off the floor and you clean up as quickly as possible. That shouldn’t be the case if it is a suspected crime scene. Ideally there should be standardized processes or protocols whenever there is suspicion. And those protocols may be different than when a patient ordinarily dies.”

Seeking Solutions

Hospitalists and other professionals—especially nurses and ancillary personnel—have an obligation to be informed and astute regarding individual characteristics and signs of suspicious patient deaths. Appropriate epidemiological, toxicological, and psychological data must be collected and analyzed routinely.

“Data about this phenomenon need to be disseminated to heighten awareness that serial murder of patients is a significant concern that extends beyond a few shocking, isolated incidents,” write Drs. Yorker and Kizer and their co-authors.

Institutional hiring practices must be changed so balance is achieved between preventing wrongful discharge or denial-of-employment lawsuits and protecting patient safety. Existing state legislation and future federal legislation for institutional immunity is an important element of patient advocacy that hospitalists can support.

Ultimately, hospitalists must be informed, aware, and alert. “Most [suspicions] will not be anything,” says Dr. Iserson. “Just pay attention to it.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Yorker BC, Kizer KW, Lampe P, et al. Serial murder by healthcare professionals. J Forensic Sci. 2006 Nov;51(6):1362-1371.

- Wolf BC, Lavezzi WA. Paths to destruction: the lives and crimes of two serial killers. J Forensic Sci. 2007 Jan;52(1):199-203.

- ASHRM. American Society for Healthcare Risk Management. A call for federal immunity to protect health care employers … and patients. Chicago: Monograph; April 1, 2005; www.ashrm.org/ashrm/resources/files/Monograph.Immunity.pdf.