User login

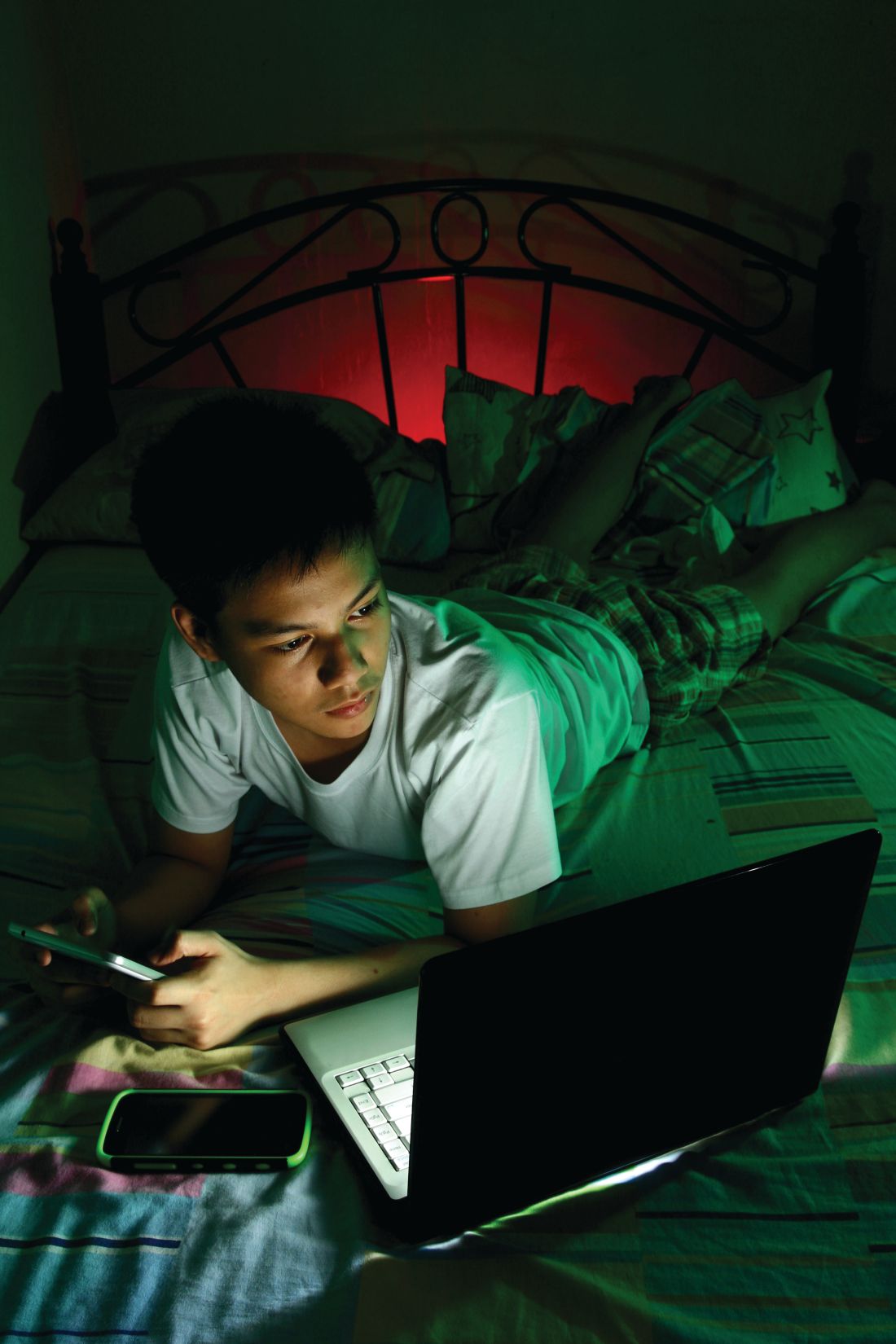

NEW ORLEANS – Social media and electronics aren’t the only barriers to a good night’s sleep for teens, according to Adiaha I. A. Spinks-Franklin, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Another half-dozen “sleep enemies” interfere with adolescents’ sleep and can contribute to insomnia or other sleep disorders, she told attendees at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Knowing what normal sleep physiology looks like in youth and understanding the most common sleep enemies and sleep-behavior problems can help you use effective interventions to help your patients get the sleep they need, she said.

Infants need the most sleep, about 12-16 hours each 24-hour period, including naps, for those aged 4-12 months. As they grow into toddlerhood and preschool age, children gradually need less: Children aged 1-2 years need 11-14 hours and children aged 3-5 years need 10-13 hours, including naps. By the time children are in school, ages 6-12, they should have dropped their naps and need 9-12 hours a night.

In fact, 75% of high school seniors get less than 8 hours of sleep a day and live with a chronic sleep debt, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Although social media use and electronics in the bedroom – TVs, computers, cell phones, and video games – can certainly contribute to inadequate sleep, a heavy academic load and extracurricular activities can be just as problematic, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Teens who work after school also may have difficulty getting enough sleep, especially if they also have to balance a heavier academic load or even one or two extracurricular activities.

Socializing with friends also can interfere with sleep, especially when get-togethers run late; drinking caffeinated drinks in the afternoon onward can make it difficult for adolescents to get the sleep they need as well. Less-modifiable contributors to too little sleep are stress and early school start times, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

The two most common sleep problems seen in teens are insomnia and delayed sleep phase syndrome. Addressing these is important because the effects of chronic insufficient sleep can have far-reaching consequences. Obesity and related chronic health conditions are associated with inadequate sleep, as are poor academic performance, poor judgment, poor executive functioning, and mental health disorders like depression.

Short-term effects of insufficient sleep also can be problematic and can exacerbate existing sleep problems, such as sleeping in on the weekends to “catch up” on sleep or drinking more caffeine to try to stay awake during the day. Increased caffeine intake can interfere with non-REM deep sleep, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said, and therefore reduce the quality of sleep even if the person gets the total hours they need.

Insomnia in adolescents

Insomnia can refer to difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, sleeping for long enough, or getting enough sleep in one period of time even when the opportunity is there. Some people may have no trouble falling asleep, but they wake up too early – before they have had gotten the sleep they need – and cannot return to sleep.

To be insomnia, the problem must occur “despite having enough time available for sleep,” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. “Patient who restrict the amount of time for sleep due to work or social commitments may have trouble sleeping and daytime sleepiness but do not have insomnia.”

Daytime impairment also is part of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s definition of insomnia. The rare teen who doesn’t need as much sleep as average and functions without difficulty during the day does not necessarily have insomnia.

But the impairment may not necessarily just be fatigue or sleepiness. In fact, many of the symptoms are the same as those seen with ADHD.

Daytime consequences of insomnia can include the following:

- Depression, feeling sad or “blue,” or emotional hypersensitivity.

- Mood swings, crankiness, or irritability.

- Difficulty concentrating or paying attention, poor memory, mind wandering, or even inability to sit still.

- Job or school problems, such as not being able to finish homework, not finishing tasks they start, or forgetfulness.

- Difficulty in social situations, such as discomfort with others or problems with friends.

- Daytime sleepiness, even when unable to actually take a nap.

- Behavioral problems, such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, or aggression.

- Frequent mistakes, especially at work, at school, or while driving (often “errors of omission,” such as not seeing a street sign or not hearing an instruction).

- Lower levels of motivation or initiative, feeling less energetic.

- Excessive worry about sleep.

Evaluation of insomnia can be framed with “the three-factor model,” which includes predisposing factors, precipitating factors, and perpetuating factors.

Predisposing factors – those that indicate a person already may be at risk for insomnia – include potential genetic influences as well as their typical response to stress. “Do they sleep more or less?” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Even teens predisposed to insomnia may not develop it, however, without a precipitating trigger.

These triggers could include stress, anxiety, poor initial sleep hygiene that becomes a pattern, dietary intake or behaviors (such as drinking caffeine or eating too much or too late in the evening), changes to their schedule, or side effects of medications.

Once insomnia begins, various factors can then perpetuate the cycle, including some of those that triggered it, such as anxiety or a school or work schedule. Sometimes it can be difficult to pinpoint the factor prolonging insomnia, such as the unconscious reward of going to work or school late with few or no consequences.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome

Delayed sleep phase syndrome occurs when someone has a delayed onset of melatonin secretion that pushes back the time when they can fall asleep. Melatonin is the neurotransmitter produced by the pineal gland that signals the start of nighttime. Although it has a hereditary component, delayed sleep phase syndrome also can result from a pattern of poor sleep onset and sleeping in on the weekends.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin described the typical cycle: A teen doesn’t go to sleep until after midnight and then wants to sleep in later in the morning. Because they have to wake up early for school, they sleep in on the weekends to try to regain the sleep they lost. Sleeping in pushes their circadian rhythm even later, perpetuating the problem.

Interventions for sleep disorders

The recommended treatment for insomnia is cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia, for which strong evidence exists. Before seeking cognitive-behavior therapy, however, families can work to improve sleep hygiene and reduce stimuli that contribute to insomnia.

Teens should avoid screens for at least 1 hour before bedtime and avoid caffeine and exercise for at least 4 hours before going to bed. They also need to develop a schedule with a consistent bedtime and wake-up time, including on the weekends. They should avoid sleeping in on the weekends or taking naps during the day, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome is more resistant to treatment and has a high recurrence rate, she said, and it requires commitment from the parent and their child to address it successfully. Teens with this condition also can start with sleep hygiene practices: a consistent wake-up time that they maintain on the weekends and no daytime naps. Phototherapy in the morning can be added to hopefully induce an earlier onset of melatonin release in the evening.

The next step is making changes to the youth’s schedule, particularly evening and/or weekend activities. They can try to gradually advance their biological clock by changing their sleep schedule.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin also briefly addressed the use of over-the-counter melatonin supplements for treating sleep problems. Melatonin can be effective for treating insomnia by improving sleep onset and sleep quality, particularly in children and teens with autism spectrum disorder or ADHD.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin had no disclosures, and her presentation used no outside funding.

NEW ORLEANS – Social media and electronics aren’t the only barriers to a good night’s sleep for teens, according to Adiaha I. A. Spinks-Franklin, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Another half-dozen “sleep enemies” interfere with adolescents’ sleep and can contribute to insomnia or other sleep disorders, she told attendees at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Knowing what normal sleep physiology looks like in youth and understanding the most common sleep enemies and sleep-behavior problems can help you use effective interventions to help your patients get the sleep they need, she said.

Infants need the most sleep, about 12-16 hours each 24-hour period, including naps, for those aged 4-12 months. As they grow into toddlerhood and preschool age, children gradually need less: Children aged 1-2 years need 11-14 hours and children aged 3-5 years need 10-13 hours, including naps. By the time children are in school, ages 6-12, they should have dropped their naps and need 9-12 hours a night.

In fact, 75% of high school seniors get less than 8 hours of sleep a day and live with a chronic sleep debt, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Although social media use and electronics in the bedroom – TVs, computers, cell phones, and video games – can certainly contribute to inadequate sleep, a heavy academic load and extracurricular activities can be just as problematic, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Teens who work after school also may have difficulty getting enough sleep, especially if they also have to balance a heavier academic load or even one or two extracurricular activities.

Socializing with friends also can interfere with sleep, especially when get-togethers run late; drinking caffeinated drinks in the afternoon onward can make it difficult for adolescents to get the sleep they need as well. Less-modifiable contributors to too little sleep are stress and early school start times, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

The two most common sleep problems seen in teens are insomnia and delayed sleep phase syndrome. Addressing these is important because the effects of chronic insufficient sleep can have far-reaching consequences. Obesity and related chronic health conditions are associated with inadequate sleep, as are poor academic performance, poor judgment, poor executive functioning, and mental health disorders like depression.

Short-term effects of insufficient sleep also can be problematic and can exacerbate existing sleep problems, such as sleeping in on the weekends to “catch up” on sleep or drinking more caffeine to try to stay awake during the day. Increased caffeine intake can interfere with non-REM deep sleep, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said, and therefore reduce the quality of sleep even if the person gets the total hours they need.

Insomnia in adolescents

Insomnia can refer to difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, sleeping for long enough, or getting enough sleep in one period of time even when the opportunity is there. Some people may have no trouble falling asleep, but they wake up too early – before they have had gotten the sleep they need – and cannot return to sleep.

To be insomnia, the problem must occur “despite having enough time available for sleep,” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. “Patient who restrict the amount of time for sleep due to work or social commitments may have trouble sleeping and daytime sleepiness but do not have insomnia.”

Daytime impairment also is part of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s definition of insomnia. The rare teen who doesn’t need as much sleep as average and functions without difficulty during the day does not necessarily have insomnia.

But the impairment may not necessarily just be fatigue or sleepiness. In fact, many of the symptoms are the same as those seen with ADHD.

Daytime consequences of insomnia can include the following:

- Depression, feeling sad or “blue,” or emotional hypersensitivity.

- Mood swings, crankiness, or irritability.

- Difficulty concentrating or paying attention, poor memory, mind wandering, or even inability to sit still.

- Job or school problems, such as not being able to finish homework, not finishing tasks they start, or forgetfulness.

- Difficulty in social situations, such as discomfort with others or problems with friends.

- Daytime sleepiness, even when unable to actually take a nap.

- Behavioral problems, such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, or aggression.

- Frequent mistakes, especially at work, at school, or while driving (often “errors of omission,” such as not seeing a street sign or not hearing an instruction).

- Lower levels of motivation or initiative, feeling less energetic.

- Excessive worry about sleep.

Evaluation of insomnia can be framed with “the three-factor model,” which includes predisposing factors, precipitating factors, and perpetuating factors.

Predisposing factors – those that indicate a person already may be at risk for insomnia – include potential genetic influences as well as their typical response to stress. “Do they sleep more or less?” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Even teens predisposed to insomnia may not develop it, however, without a precipitating trigger.

These triggers could include stress, anxiety, poor initial sleep hygiene that becomes a pattern, dietary intake or behaviors (such as drinking caffeine or eating too much or too late in the evening), changes to their schedule, or side effects of medications.

Once insomnia begins, various factors can then perpetuate the cycle, including some of those that triggered it, such as anxiety or a school or work schedule. Sometimes it can be difficult to pinpoint the factor prolonging insomnia, such as the unconscious reward of going to work or school late with few or no consequences.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome

Delayed sleep phase syndrome occurs when someone has a delayed onset of melatonin secretion that pushes back the time when they can fall asleep. Melatonin is the neurotransmitter produced by the pineal gland that signals the start of nighttime. Although it has a hereditary component, delayed sleep phase syndrome also can result from a pattern of poor sleep onset and sleeping in on the weekends.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin described the typical cycle: A teen doesn’t go to sleep until after midnight and then wants to sleep in later in the morning. Because they have to wake up early for school, they sleep in on the weekends to try to regain the sleep they lost. Sleeping in pushes their circadian rhythm even later, perpetuating the problem.

Interventions for sleep disorders

The recommended treatment for insomnia is cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia, for which strong evidence exists. Before seeking cognitive-behavior therapy, however, families can work to improve sleep hygiene and reduce stimuli that contribute to insomnia.

Teens should avoid screens for at least 1 hour before bedtime and avoid caffeine and exercise for at least 4 hours before going to bed. They also need to develop a schedule with a consistent bedtime and wake-up time, including on the weekends. They should avoid sleeping in on the weekends or taking naps during the day, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome is more resistant to treatment and has a high recurrence rate, she said, and it requires commitment from the parent and their child to address it successfully. Teens with this condition also can start with sleep hygiene practices: a consistent wake-up time that they maintain on the weekends and no daytime naps. Phototherapy in the morning can be added to hopefully induce an earlier onset of melatonin release in the evening.

The next step is making changes to the youth’s schedule, particularly evening and/or weekend activities. They can try to gradually advance their biological clock by changing their sleep schedule.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin also briefly addressed the use of over-the-counter melatonin supplements for treating sleep problems. Melatonin can be effective for treating insomnia by improving sleep onset and sleep quality, particularly in children and teens with autism spectrum disorder or ADHD.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin had no disclosures, and her presentation used no outside funding.

NEW ORLEANS – Social media and electronics aren’t the only barriers to a good night’s sleep for teens, according to Adiaha I. A. Spinks-Franklin, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Another half-dozen “sleep enemies” interfere with adolescents’ sleep and can contribute to insomnia or other sleep disorders, she told attendees at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Knowing what normal sleep physiology looks like in youth and understanding the most common sleep enemies and sleep-behavior problems can help you use effective interventions to help your patients get the sleep they need, she said.

Infants need the most sleep, about 12-16 hours each 24-hour period, including naps, for those aged 4-12 months. As they grow into toddlerhood and preschool age, children gradually need less: Children aged 1-2 years need 11-14 hours and children aged 3-5 years need 10-13 hours, including naps. By the time children are in school, ages 6-12, they should have dropped their naps and need 9-12 hours a night.

In fact, 75% of high school seniors get less than 8 hours of sleep a day and live with a chronic sleep debt, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Although social media use and electronics in the bedroom – TVs, computers, cell phones, and video games – can certainly contribute to inadequate sleep, a heavy academic load and extracurricular activities can be just as problematic, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Teens who work after school also may have difficulty getting enough sleep, especially if they also have to balance a heavier academic load or even one or two extracurricular activities.

Socializing with friends also can interfere with sleep, especially when get-togethers run late; drinking caffeinated drinks in the afternoon onward can make it difficult for adolescents to get the sleep they need as well. Less-modifiable contributors to too little sleep are stress and early school start times, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

The two most common sleep problems seen in teens are insomnia and delayed sleep phase syndrome. Addressing these is important because the effects of chronic insufficient sleep can have far-reaching consequences. Obesity and related chronic health conditions are associated with inadequate sleep, as are poor academic performance, poor judgment, poor executive functioning, and mental health disorders like depression.

Short-term effects of insufficient sleep also can be problematic and can exacerbate existing sleep problems, such as sleeping in on the weekends to “catch up” on sleep or drinking more caffeine to try to stay awake during the day. Increased caffeine intake can interfere with non-REM deep sleep, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said, and therefore reduce the quality of sleep even if the person gets the total hours they need.

Insomnia in adolescents

Insomnia can refer to difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, sleeping for long enough, or getting enough sleep in one period of time even when the opportunity is there. Some people may have no trouble falling asleep, but they wake up too early – before they have had gotten the sleep they need – and cannot return to sleep.

To be insomnia, the problem must occur “despite having enough time available for sleep,” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. “Patient who restrict the amount of time for sleep due to work or social commitments may have trouble sleeping and daytime sleepiness but do not have insomnia.”

Daytime impairment also is part of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s definition of insomnia. The rare teen who doesn’t need as much sleep as average and functions without difficulty during the day does not necessarily have insomnia.

But the impairment may not necessarily just be fatigue or sleepiness. In fact, many of the symptoms are the same as those seen with ADHD.

Daytime consequences of insomnia can include the following:

- Depression, feeling sad or “blue,” or emotional hypersensitivity.

- Mood swings, crankiness, or irritability.

- Difficulty concentrating or paying attention, poor memory, mind wandering, or even inability to sit still.

- Job or school problems, such as not being able to finish homework, not finishing tasks they start, or forgetfulness.

- Difficulty in social situations, such as discomfort with others or problems with friends.

- Daytime sleepiness, even when unable to actually take a nap.

- Behavioral problems, such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, or aggression.

- Frequent mistakes, especially at work, at school, or while driving (often “errors of omission,” such as not seeing a street sign or not hearing an instruction).

- Lower levels of motivation or initiative, feeling less energetic.

- Excessive worry about sleep.

Evaluation of insomnia can be framed with “the three-factor model,” which includes predisposing factors, precipitating factors, and perpetuating factors.

Predisposing factors – those that indicate a person already may be at risk for insomnia – include potential genetic influences as well as their typical response to stress. “Do they sleep more or less?” Dr. Spinks-Franklin said. Even teens predisposed to insomnia may not develop it, however, without a precipitating trigger.

These triggers could include stress, anxiety, poor initial sleep hygiene that becomes a pattern, dietary intake or behaviors (such as drinking caffeine or eating too much or too late in the evening), changes to their schedule, or side effects of medications.

Once insomnia begins, various factors can then perpetuate the cycle, including some of those that triggered it, such as anxiety or a school or work schedule. Sometimes it can be difficult to pinpoint the factor prolonging insomnia, such as the unconscious reward of going to work or school late with few or no consequences.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome

Delayed sleep phase syndrome occurs when someone has a delayed onset of melatonin secretion that pushes back the time when they can fall asleep. Melatonin is the neurotransmitter produced by the pineal gland that signals the start of nighttime. Although it has a hereditary component, delayed sleep phase syndrome also can result from a pattern of poor sleep onset and sleeping in on the weekends.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin described the typical cycle: A teen doesn’t go to sleep until after midnight and then wants to sleep in later in the morning. Because they have to wake up early for school, they sleep in on the weekends to try to regain the sleep they lost. Sleeping in pushes their circadian rhythm even later, perpetuating the problem.

Interventions for sleep disorders

The recommended treatment for insomnia is cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia, for which strong evidence exists. Before seeking cognitive-behavior therapy, however, families can work to improve sleep hygiene and reduce stimuli that contribute to insomnia.

Teens should avoid screens for at least 1 hour before bedtime and avoid caffeine and exercise for at least 4 hours before going to bed. They also need to develop a schedule with a consistent bedtime and wake-up time, including on the weekends. They should avoid sleeping in on the weekends or taking naps during the day, Dr. Spinks-Franklin said.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome is more resistant to treatment and has a high recurrence rate, she said, and it requires commitment from the parent and their child to address it successfully. Teens with this condition also can start with sleep hygiene practices: a consistent wake-up time that they maintain on the weekends and no daytime naps. Phototherapy in the morning can be added to hopefully induce an earlier onset of melatonin release in the evening.

The next step is making changes to the youth’s schedule, particularly evening and/or weekend activities. They can try to gradually advance their biological clock by changing their sleep schedule.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin also briefly addressed the use of over-the-counter melatonin supplements for treating sleep problems. Melatonin can be effective for treating insomnia by improving sleep onset and sleep quality, particularly in children and teens with autism spectrum disorder or ADHD.

Dr. Spinks-Franklin had no disclosures, and her presentation used no outside funding.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 19