User login

Remarkable progress has been made over the past 30-plus years in the identification of the human immunodeficiency virus, in the development of drugs to treat HIV infection, and in providing access and assuring adherence to these increasingly effective therapies. As a result, we can now offer women with HIV infection a significantly improved prognosis as well as a very high likelihood of having children who will not be infected with HIV.

While HIV infection is still an incurable, lifelong disease, it has in many ways become a chronic disease just like many other chronic diseases – a status that just a generation ago would have been a pipe dream. Today when I see a patient who has hypertension, diabetes, and HIV infection, I am often more worried about managing the hypertension and diabetes than I am about managing the HIV.

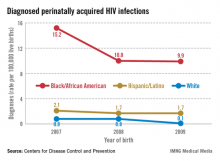

In my state of New York, for example, the number of babies born with HIV infection 15 years ago was approximately 100; in 2010, this number was 3.

Whether we practice in an area of high or low prevalence, we each have a responsibility to identify HIV-infected women and, in the context of pregnancy, to ensure that each patient’s prognosis is optimized, and perinatal transmission is prevented by bringing her viral load to an undetectable level. In cases in which an uninfected woman is considering pregnancy and her partner is HIV infected, periconception administration of antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis is a new and promising tool.

Identifying patients

None of these benefits can be provided to HIV-infected women if their status is unknown. Just as we have to measure blood pressure in order to be able to treat hypertension, we must ensure that women in our practices know their HIV status so that they can avail themselves of the remarkable advances that have been made in the care of HIV infection and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Testing appropriately is part of our role.

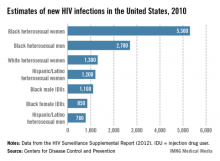

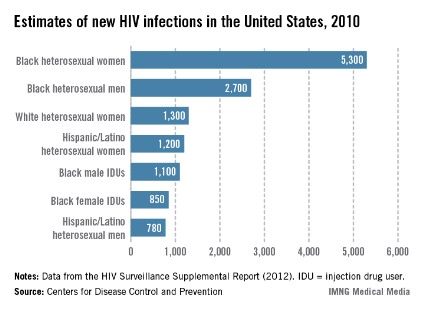

Certainly, HIV incidence and risk for infection vary across the United States; there are dramatic differences in risk, for instance, between Des Moines, where prevalence is low, and Washington, D.C., where almost 3% of the population is infected with HIV. Still, regardless of geography, we must appreciate that the impact of the epidemic on women has grown significantly over time, such that women now account for approximately one in four people living with HIV, according to the CDC.

What is especially important for us to appreciate is the fact that a sizable portion of all people with HIV still do not know their HIV status. The CDC estimates that approximately 18% of all HIV-infected individuals are unaware of their status.

A significant percentage of the children who are infected, moreover, were born to women whose status was unknown. According to the CDC, approximately 27% of the mothers of HIV-infected infants reported from 2003 to 2007 were diagnosed with HIV after delivery, and only 29% of the mothers of infected infants received antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy.

The CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other national organizations have long called for universal prenatal HIV testing to improve the health outcomes of the mother and infant.

On a broader level, the approach to testing has evolved. In 2006, the CDC moved away from targeted risk-based HIV testing recommendations and advised routine opt-out testing for all patients aged 13-64 years. The agency concluded that universal testing is more effective largely because many patients found to be infected did not consider themselves to be at risk. ACOG weighed in the following year, also recommending universal testing with patient notification and an opt-out option, which removes the need for detailed, testing-related informed consent.

Some state laws do not allow opt-out testing and still require affirmative consent, however, so it is important to know your state’s laws. Regardless of your state’s situation, however, failing to test because you deem a patient unlikely to be infected is no longer acceptable.

Testing should be approached just as a blood pressure check is approached – as part of a routine battery of tests that is performed unless the patient declines.

Although the adverse consequences of being identified as HIV positive remain to some extent, it is by no means as severe as it was in the 1980s, when women with positive test results were stigmatized and discriminated against. As primary care providers, we should be reassuring in this regard and much more assertive in making sure patients understand the benefits of testing.

In a related move this year, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is recommending that all patients aged 15-65 years should be screened for HIV, regardless of their risk level.

Treating infection

Strategies for preventing perinatal transmission and managing HIV disease in pregnancy are evolving so rapidly that it is often best for obstetricians who see only a few HIV-infected patients a year to work in consultation with an obstetrician with expertise in HIV in pregnancy, an infectious disease specialist or HIV specialty care provider, or an internist with expert knowledge of the antiretroviral drugs. The National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women, last updated in July 2012, can be a useful reference.

The latest generation of ARV drugs are not only more effective, but also many require only once-a-day dosing schedules, which can improve patient adherence. On the flip side, there are dozens of choices for individualizing treatment, making treatment decisions much more complex than a decade ago.

Among the important trends and changes for ob.gyns to be aware of are the following:

• A "test and treat" paradigm. We are entering a "test and treat" era in the treatment of HIV infection overall, with the paradigm shifting to a much more liberal and immediate recourse to therapy for HIV-infected adults.

Previously, regular monitoring of virologic status would help guide the timing of therapy initiation. For example, CD4 T-lymphocyte counts of less than 350 mm3 or plasma HIV RNA levels that exceeded certain thresholds were the recommended triggers for initiation of ARV therapy. Although there remains some disagreement among experts who support treating a patient when CD4 counts reach 550 mm3 and experts who support treating a patient regardless of CD4 or viral load, I believe the scale is tipping toward treating almost everyone upon diagnosis. Waiting until patients have become more immunocompromised and reached a chronic infection–induced inflammatory state can drive the development of cardiovascular disease and other long-term health care problems.

While some debate persists as to whether all HIV-infected individuals should begin treatment regardless of CD4 count, there is no question as to the appropriate approach for the pregnant woman.

For HIV-infected pregnant women, it is currently recommended that a combination ARV drug regimen be implemented as early as possible antepartum to prevent perinatal transmission, regardless of HIV RNA copy number or CD4 T-lymphocyte count. Evidence that transmission may be lowered with earlier initiation of ART, combined with growing evidence regarding the safety of ARV drugs, has shifted the mindset from a paradigm of avoiding therapy in the first trimester unless absolutely necessary, to a slightly more aggressive approach with earlier initiation of ARV drugs.

Women who enter pregnancy on an effective ARV regimen should continue this regimen without disruption, as drugs changes during pregnancy may be associated with loss of viral control and increased risk of perinatal transmission.

• Lessening concern about risks. Certainly, the known benefits of ARV drugs for a pregnant woman must be weighed against the potential risks of adverse events to the woman, fetus, and newborn. The NIH clinical guidelines categorize various antiretroviral agents for use in pregnancy as preferred, alternative, or for "use in special circumstances."

In general, however, we have acquired more information on the safety of many of these drugs in pregnancy. As data have accumulated, concerns about potential teratogenic effects and other adverse effects of ARV drugs on fetuses and newborns have lessened.

For example, long-standing concerns about tenofovir decreasing fetal bone porosity and potentially causing other anomalies have lessened with recent studies suggesting that adverse events from tenofovir occur infrequently. The use of other drugs, such as efavirenz, also has been liberalized with recent evidence showing that the risk of adverse events is much lower than once believed; recent guidelines now advise that efavirenz rarely needs to be discontinued among women who were receiving it prior to pregnancy.

Obstetricians’ chief role in working with consultants is to ensure that a less-effective drug is not prescribed merely because a patient is pregnant. An effective Class C drug should not be replaced by an ineffective Class B drug solely because an internist does not understand drug use in pregnancy. Obstetricians understand that risks of drugs must be balanced against the risks of untreated diseases.

We sometimes prescribe antiseizure drugs and other category D medications during pregnancy when the benefits outweigh the risks, and preventing HIV transmission from mother to fetus is no different. Suppressing the virus is the primary goal in HIV treatment today, and pregnancy should not preclude the use of therapeutics that can attain that goal.

• New intrapartum approach. Probably the most significant recent change to the NIH guidelines concerns the use of intravenous zidovudine (AZT) during labor in women infected with HIV.

Parenteral AZT had been the standard of care since 1994; however, the 2012 guidelines state that AZT is no longer required during labor for HIV-infected women who are receiving combination antiretroviral regimens and who have an undetectable viral load (HIV RNA less than 400 copies/mL near delivery). Studies have shown that with these two criteria met, the transmission rate is low enough that there is no reason to believe that AZT would provide any additional benefit.

Utilizing the Ob. skill set

The choice of drug regiments for HIV-infected pregnant women should be based on the same principles used to choose regimens for nonpregnant individuals, and it is the obstetrician’s job – not the job of the internist or other expert – to decide whether there are compelling pregnancy-specific reasons that should cause modifications.

When there is concern about an elevated risk of preterm birth, as there is with the use of protease inhibitors in the first trimester, obstetricians can utilize cervical length screening and/or appropriate techniques and approaches for monitoring patients, just as they would monitor other patients with elevated risk.

Obstetricians also can also bring their expertise and knowledge of current obstetrical technologies to the table when it comes to the use of amniocentesis in HIV-infected pregnant women. The risks of amniocentesis are minimal (no perinatal transmissions have been reported after amniocentesis in women without detectable virus and on effective ART), but any small potential or perceived risk can be further reduced by using new tests that allow a determination of the likelihood of chromosomal abnormalities through peripheral blood sampling. If a patient’s peripheral blood status is indicative of lower-than-expected risks of aneuploidy, for instance, the patient may decide she can forego amniocentesis.

Additionally, the field of safe reproduction for HIV-discordant couples is progressing. Data from the NIH-supported HPTN 052 randomized clinical trial show that early initiation of ART in the infected partner significantly reduces HIV transmission to the uninfected partner.

Although not as well studied, periconception administration of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-uninfected partners may offer an additional tool for reducing the risk of sexual transmission. (The NIH guidelines for use of ARV drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women include a section on "Reproductive Options of HIV-Concordant and Serodiscordant Couples.")

Uninfected women should be regularly counseled about consistent condom use, but especially in cases in which couples are opposed to protected intercourse and the use of assisted reproductive techniques (sperm preparation techniques coupled with either intrauterine insemination or in vitro fertilization), the use of antiretroviral medications by uninfected women may provide for safer conception.

Dr. Minkoff serves as chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Maimonides Medical Center in New York and is a distinguished professor of obstetrics and gynecology at State University of New York–Health Science Center. Hef has published extensively on HIV detection and treatment and has been involved over the years on numerous panels, task forces, and guideline committees dealing with the care of HIV-infected women. He currently serves on the panel for the National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women.

Dr. Minkoff reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Remarkable progress has been made over the past 30-plus years in the identification of the human immunodeficiency virus, in the development of drugs to treat HIV infection, and in providing access and assuring adherence to these increasingly effective therapies. As a result, we can now offer women with HIV infection a significantly improved prognosis as well as a very high likelihood of having children who will not be infected with HIV.

While HIV infection is still an incurable, lifelong disease, it has in many ways become a chronic disease just like many other chronic diseases – a status that just a generation ago would have been a pipe dream. Today when I see a patient who has hypertension, diabetes, and HIV infection, I am often more worried about managing the hypertension and diabetes than I am about managing the HIV.

In my state of New York, for example, the number of babies born with HIV infection 15 years ago was approximately 100; in 2010, this number was 3.

Whether we practice in an area of high or low prevalence, we each have a responsibility to identify HIV-infected women and, in the context of pregnancy, to ensure that each patient’s prognosis is optimized, and perinatal transmission is prevented by bringing her viral load to an undetectable level. In cases in which an uninfected woman is considering pregnancy and her partner is HIV infected, periconception administration of antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis is a new and promising tool.

Identifying patients

None of these benefits can be provided to HIV-infected women if their status is unknown. Just as we have to measure blood pressure in order to be able to treat hypertension, we must ensure that women in our practices know their HIV status so that they can avail themselves of the remarkable advances that have been made in the care of HIV infection and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Testing appropriately is part of our role.

Certainly, HIV incidence and risk for infection vary across the United States; there are dramatic differences in risk, for instance, between Des Moines, where prevalence is low, and Washington, D.C., where almost 3% of the population is infected with HIV. Still, regardless of geography, we must appreciate that the impact of the epidemic on women has grown significantly over time, such that women now account for approximately one in four people living with HIV, according to the CDC.

What is especially important for us to appreciate is the fact that a sizable portion of all people with HIV still do not know their HIV status. The CDC estimates that approximately 18% of all HIV-infected individuals are unaware of their status.

A significant percentage of the children who are infected, moreover, were born to women whose status was unknown. According to the CDC, approximately 27% of the mothers of HIV-infected infants reported from 2003 to 2007 were diagnosed with HIV after delivery, and only 29% of the mothers of infected infants received antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy.

The CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other national organizations have long called for universal prenatal HIV testing to improve the health outcomes of the mother and infant.

On a broader level, the approach to testing has evolved. In 2006, the CDC moved away from targeted risk-based HIV testing recommendations and advised routine opt-out testing for all patients aged 13-64 years. The agency concluded that universal testing is more effective largely because many patients found to be infected did not consider themselves to be at risk. ACOG weighed in the following year, also recommending universal testing with patient notification and an opt-out option, which removes the need for detailed, testing-related informed consent.

Some state laws do not allow opt-out testing and still require affirmative consent, however, so it is important to know your state’s laws. Regardless of your state’s situation, however, failing to test because you deem a patient unlikely to be infected is no longer acceptable.

Testing should be approached just as a blood pressure check is approached – as part of a routine battery of tests that is performed unless the patient declines.

Although the adverse consequences of being identified as HIV positive remain to some extent, it is by no means as severe as it was in the 1980s, when women with positive test results were stigmatized and discriminated against. As primary care providers, we should be reassuring in this regard and much more assertive in making sure patients understand the benefits of testing.

In a related move this year, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is recommending that all patients aged 15-65 years should be screened for HIV, regardless of their risk level.

Treating infection

Strategies for preventing perinatal transmission and managing HIV disease in pregnancy are evolving so rapidly that it is often best for obstetricians who see only a few HIV-infected patients a year to work in consultation with an obstetrician with expertise in HIV in pregnancy, an infectious disease specialist or HIV specialty care provider, or an internist with expert knowledge of the antiretroviral drugs. The National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women, last updated in July 2012, can be a useful reference.

The latest generation of ARV drugs are not only more effective, but also many require only once-a-day dosing schedules, which can improve patient adherence. On the flip side, there are dozens of choices for individualizing treatment, making treatment decisions much more complex than a decade ago.

Among the important trends and changes for ob.gyns to be aware of are the following:

• A "test and treat" paradigm. We are entering a "test and treat" era in the treatment of HIV infection overall, with the paradigm shifting to a much more liberal and immediate recourse to therapy for HIV-infected adults.

Previously, regular monitoring of virologic status would help guide the timing of therapy initiation. For example, CD4 T-lymphocyte counts of less than 350 mm3 or plasma HIV RNA levels that exceeded certain thresholds were the recommended triggers for initiation of ARV therapy. Although there remains some disagreement among experts who support treating a patient when CD4 counts reach 550 mm3 and experts who support treating a patient regardless of CD4 or viral load, I believe the scale is tipping toward treating almost everyone upon diagnosis. Waiting until patients have become more immunocompromised and reached a chronic infection–induced inflammatory state can drive the development of cardiovascular disease and other long-term health care problems.

While some debate persists as to whether all HIV-infected individuals should begin treatment regardless of CD4 count, there is no question as to the appropriate approach for the pregnant woman.

For HIV-infected pregnant women, it is currently recommended that a combination ARV drug regimen be implemented as early as possible antepartum to prevent perinatal transmission, regardless of HIV RNA copy number or CD4 T-lymphocyte count. Evidence that transmission may be lowered with earlier initiation of ART, combined with growing evidence regarding the safety of ARV drugs, has shifted the mindset from a paradigm of avoiding therapy in the first trimester unless absolutely necessary, to a slightly more aggressive approach with earlier initiation of ARV drugs.

Women who enter pregnancy on an effective ARV regimen should continue this regimen without disruption, as drugs changes during pregnancy may be associated with loss of viral control and increased risk of perinatal transmission.

• Lessening concern about risks. Certainly, the known benefits of ARV drugs for a pregnant woman must be weighed against the potential risks of adverse events to the woman, fetus, and newborn. The NIH clinical guidelines categorize various antiretroviral agents for use in pregnancy as preferred, alternative, or for "use in special circumstances."

In general, however, we have acquired more information on the safety of many of these drugs in pregnancy. As data have accumulated, concerns about potential teratogenic effects and other adverse effects of ARV drugs on fetuses and newborns have lessened.

For example, long-standing concerns about tenofovir decreasing fetal bone porosity and potentially causing other anomalies have lessened with recent studies suggesting that adverse events from tenofovir occur infrequently. The use of other drugs, such as efavirenz, also has been liberalized with recent evidence showing that the risk of adverse events is much lower than once believed; recent guidelines now advise that efavirenz rarely needs to be discontinued among women who were receiving it prior to pregnancy.

Obstetricians’ chief role in working with consultants is to ensure that a less-effective drug is not prescribed merely because a patient is pregnant. An effective Class C drug should not be replaced by an ineffective Class B drug solely because an internist does not understand drug use in pregnancy. Obstetricians understand that risks of drugs must be balanced against the risks of untreated diseases.

We sometimes prescribe antiseizure drugs and other category D medications during pregnancy when the benefits outweigh the risks, and preventing HIV transmission from mother to fetus is no different. Suppressing the virus is the primary goal in HIV treatment today, and pregnancy should not preclude the use of therapeutics that can attain that goal.

• New intrapartum approach. Probably the most significant recent change to the NIH guidelines concerns the use of intravenous zidovudine (AZT) during labor in women infected with HIV.

Parenteral AZT had been the standard of care since 1994; however, the 2012 guidelines state that AZT is no longer required during labor for HIV-infected women who are receiving combination antiretroviral regimens and who have an undetectable viral load (HIV RNA less than 400 copies/mL near delivery). Studies have shown that with these two criteria met, the transmission rate is low enough that there is no reason to believe that AZT would provide any additional benefit.

Utilizing the Ob. skill set

The choice of drug regiments for HIV-infected pregnant women should be based on the same principles used to choose regimens for nonpregnant individuals, and it is the obstetrician’s job – not the job of the internist or other expert – to decide whether there are compelling pregnancy-specific reasons that should cause modifications.

When there is concern about an elevated risk of preterm birth, as there is with the use of protease inhibitors in the first trimester, obstetricians can utilize cervical length screening and/or appropriate techniques and approaches for monitoring patients, just as they would monitor other patients with elevated risk.

Obstetricians also can also bring their expertise and knowledge of current obstetrical technologies to the table when it comes to the use of amniocentesis in HIV-infected pregnant women. The risks of amniocentesis are minimal (no perinatal transmissions have been reported after amniocentesis in women without detectable virus and on effective ART), but any small potential or perceived risk can be further reduced by using new tests that allow a determination of the likelihood of chromosomal abnormalities through peripheral blood sampling. If a patient’s peripheral blood status is indicative of lower-than-expected risks of aneuploidy, for instance, the patient may decide she can forego amniocentesis.

Additionally, the field of safe reproduction for HIV-discordant couples is progressing. Data from the NIH-supported HPTN 052 randomized clinical trial show that early initiation of ART in the infected partner significantly reduces HIV transmission to the uninfected partner.

Although not as well studied, periconception administration of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-uninfected partners may offer an additional tool for reducing the risk of sexual transmission. (The NIH guidelines for use of ARV drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women include a section on "Reproductive Options of HIV-Concordant and Serodiscordant Couples.")

Uninfected women should be regularly counseled about consistent condom use, but especially in cases in which couples are opposed to protected intercourse and the use of assisted reproductive techniques (sperm preparation techniques coupled with either intrauterine insemination or in vitro fertilization), the use of antiretroviral medications by uninfected women may provide for safer conception.

Dr. Minkoff serves as chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Maimonides Medical Center in New York and is a distinguished professor of obstetrics and gynecology at State University of New York–Health Science Center. Hef has published extensively on HIV detection and treatment and has been involved over the years on numerous panels, task forces, and guideline committees dealing with the care of HIV-infected women. He currently serves on the panel for the National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women.

Dr. Minkoff reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Remarkable progress has been made over the past 30-plus years in the identification of the human immunodeficiency virus, in the development of drugs to treat HIV infection, and in providing access and assuring adherence to these increasingly effective therapies. As a result, we can now offer women with HIV infection a significantly improved prognosis as well as a very high likelihood of having children who will not be infected with HIV.

While HIV infection is still an incurable, lifelong disease, it has in many ways become a chronic disease just like many other chronic diseases – a status that just a generation ago would have been a pipe dream. Today when I see a patient who has hypertension, diabetes, and HIV infection, I am often more worried about managing the hypertension and diabetes than I am about managing the HIV.

In my state of New York, for example, the number of babies born with HIV infection 15 years ago was approximately 100; in 2010, this number was 3.

Whether we practice in an area of high or low prevalence, we each have a responsibility to identify HIV-infected women and, in the context of pregnancy, to ensure that each patient’s prognosis is optimized, and perinatal transmission is prevented by bringing her viral load to an undetectable level. In cases in which an uninfected woman is considering pregnancy and her partner is HIV infected, periconception administration of antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis is a new and promising tool.

Identifying patients

None of these benefits can be provided to HIV-infected women if their status is unknown. Just as we have to measure blood pressure in order to be able to treat hypertension, we must ensure that women in our practices know their HIV status so that they can avail themselves of the remarkable advances that have been made in the care of HIV infection and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Testing appropriately is part of our role.

Certainly, HIV incidence and risk for infection vary across the United States; there are dramatic differences in risk, for instance, between Des Moines, where prevalence is low, and Washington, D.C., where almost 3% of the population is infected with HIV. Still, regardless of geography, we must appreciate that the impact of the epidemic on women has grown significantly over time, such that women now account for approximately one in four people living with HIV, according to the CDC.

What is especially important for us to appreciate is the fact that a sizable portion of all people with HIV still do not know their HIV status. The CDC estimates that approximately 18% of all HIV-infected individuals are unaware of their status.

A significant percentage of the children who are infected, moreover, were born to women whose status was unknown. According to the CDC, approximately 27% of the mothers of HIV-infected infants reported from 2003 to 2007 were diagnosed with HIV after delivery, and only 29% of the mothers of infected infants received antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy.

The CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other national organizations have long called for universal prenatal HIV testing to improve the health outcomes of the mother and infant.

On a broader level, the approach to testing has evolved. In 2006, the CDC moved away from targeted risk-based HIV testing recommendations and advised routine opt-out testing for all patients aged 13-64 years. The agency concluded that universal testing is more effective largely because many patients found to be infected did not consider themselves to be at risk. ACOG weighed in the following year, also recommending universal testing with patient notification and an opt-out option, which removes the need for detailed, testing-related informed consent.

Some state laws do not allow opt-out testing and still require affirmative consent, however, so it is important to know your state’s laws. Regardless of your state’s situation, however, failing to test because you deem a patient unlikely to be infected is no longer acceptable.

Testing should be approached just as a blood pressure check is approached – as part of a routine battery of tests that is performed unless the patient declines.

Although the adverse consequences of being identified as HIV positive remain to some extent, it is by no means as severe as it was in the 1980s, when women with positive test results were stigmatized and discriminated against. As primary care providers, we should be reassuring in this regard and much more assertive in making sure patients understand the benefits of testing.

In a related move this year, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is recommending that all patients aged 15-65 years should be screened for HIV, regardless of their risk level.

Treating infection

Strategies for preventing perinatal transmission and managing HIV disease in pregnancy are evolving so rapidly that it is often best for obstetricians who see only a few HIV-infected patients a year to work in consultation with an obstetrician with expertise in HIV in pregnancy, an infectious disease specialist or HIV specialty care provider, or an internist with expert knowledge of the antiretroviral drugs. The National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women, last updated in July 2012, can be a useful reference.

The latest generation of ARV drugs are not only more effective, but also many require only once-a-day dosing schedules, which can improve patient adherence. On the flip side, there are dozens of choices for individualizing treatment, making treatment decisions much more complex than a decade ago.

Among the important trends and changes for ob.gyns to be aware of are the following:

• A "test and treat" paradigm. We are entering a "test and treat" era in the treatment of HIV infection overall, with the paradigm shifting to a much more liberal and immediate recourse to therapy for HIV-infected adults.

Previously, regular monitoring of virologic status would help guide the timing of therapy initiation. For example, CD4 T-lymphocyte counts of less than 350 mm3 or plasma HIV RNA levels that exceeded certain thresholds were the recommended triggers for initiation of ARV therapy. Although there remains some disagreement among experts who support treating a patient when CD4 counts reach 550 mm3 and experts who support treating a patient regardless of CD4 or viral load, I believe the scale is tipping toward treating almost everyone upon diagnosis. Waiting until patients have become more immunocompromised and reached a chronic infection–induced inflammatory state can drive the development of cardiovascular disease and other long-term health care problems.

While some debate persists as to whether all HIV-infected individuals should begin treatment regardless of CD4 count, there is no question as to the appropriate approach for the pregnant woman.

For HIV-infected pregnant women, it is currently recommended that a combination ARV drug regimen be implemented as early as possible antepartum to prevent perinatal transmission, regardless of HIV RNA copy number or CD4 T-lymphocyte count. Evidence that transmission may be lowered with earlier initiation of ART, combined with growing evidence regarding the safety of ARV drugs, has shifted the mindset from a paradigm of avoiding therapy in the first trimester unless absolutely necessary, to a slightly more aggressive approach with earlier initiation of ARV drugs.

Women who enter pregnancy on an effective ARV regimen should continue this regimen without disruption, as drugs changes during pregnancy may be associated with loss of viral control and increased risk of perinatal transmission.

• Lessening concern about risks. Certainly, the known benefits of ARV drugs for a pregnant woman must be weighed against the potential risks of adverse events to the woman, fetus, and newborn. The NIH clinical guidelines categorize various antiretroviral agents for use in pregnancy as preferred, alternative, or for "use in special circumstances."

In general, however, we have acquired more information on the safety of many of these drugs in pregnancy. As data have accumulated, concerns about potential teratogenic effects and other adverse effects of ARV drugs on fetuses and newborns have lessened.

For example, long-standing concerns about tenofovir decreasing fetal bone porosity and potentially causing other anomalies have lessened with recent studies suggesting that adverse events from tenofovir occur infrequently. The use of other drugs, such as efavirenz, also has been liberalized with recent evidence showing that the risk of adverse events is much lower than once believed; recent guidelines now advise that efavirenz rarely needs to be discontinued among women who were receiving it prior to pregnancy.

Obstetricians’ chief role in working with consultants is to ensure that a less-effective drug is not prescribed merely because a patient is pregnant. An effective Class C drug should not be replaced by an ineffective Class B drug solely because an internist does not understand drug use in pregnancy. Obstetricians understand that risks of drugs must be balanced against the risks of untreated diseases.

We sometimes prescribe antiseizure drugs and other category D medications during pregnancy when the benefits outweigh the risks, and preventing HIV transmission from mother to fetus is no different. Suppressing the virus is the primary goal in HIV treatment today, and pregnancy should not preclude the use of therapeutics that can attain that goal.

• New intrapartum approach. Probably the most significant recent change to the NIH guidelines concerns the use of intravenous zidovudine (AZT) during labor in women infected with HIV.

Parenteral AZT had been the standard of care since 1994; however, the 2012 guidelines state that AZT is no longer required during labor for HIV-infected women who are receiving combination antiretroviral regimens and who have an undetectable viral load (HIV RNA less than 400 copies/mL near delivery). Studies have shown that with these two criteria met, the transmission rate is low enough that there is no reason to believe that AZT would provide any additional benefit.

Utilizing the Ob. skill set

The choice of drug regiments for HIV-infected pregnant women should be based on the same principles used to choose regimens for nonpregnant individuals, and it is the obstetrician’s job – not the job of the internist or other expert – to decide whether there are compelling pregnancy-specific reasons that should cause modifications.

When there is concern about an elevated risk of preterm birth, as there is with the use of protease inhibitors in the first trimester, obstetricians can utilize cervical length screening and/or appropriate techniques and approaches for monitoring patients, just as they would monitor other patients with elevated risk.

Obstetricians also can also bring their expertise and knowledge of current obstetrical technologies to the table when it comes to the use of amniocentesis in HIV-infected pregnant women. The risks of amniocentesis are minimal (no perinatal transmissions have been reported after amniocentesis in women without detectable virus and on effective ART), but any small potential or perceived risk can be further reduced by using new tests that allow a determination of the likelihood of chromosomal abnormalities through peripheral blood sampling. If a patient’s peripheral blood status is indicative of lower-than-expected risks of aneuploidy, for instance, the patient may decide she can forego amniocentesis.

Additionally, the field of safe reproduction for HIV-discordant couples is progressing. Data from the NIH-supported HPTN 052 randomized clinical trial show that early initiation of ART in the infected partner significantly reduces HIV transmission to the uninfected partner.

Although not as well studied, periconception administration of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-uninfected partners may offer an additional tool for reducing the risk of sexual transmission. (The NIH guidelines for use of ARV drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women include a section on "Reproductive Options of HIV-Concordant and Serodiscordant Couples.")

Uninfected women should be regularly counseled about consistent condom use, but especially in cases in which couples are opposed to protected intercourse and the use of assisted reproductive techniques (sperm preparation techniques coupled with either intrauterine insemination or in vitro fertilization), the use of antiretroviral medications by uninfected women may provide for safer conception.

Dr. Minkoff serves as chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Maimonides Medical Center in New York and is a distinguished professor of obstetrics and gynecology at State University of New York–Health Science Center. Hef has published extensively on HIV detection and treatment and has been involved over the years on numerous panels, task forces, and guideline committees dealing with the care of HIV-infected women. He currently serves on the panel for the National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women.

Dr. Minkoff reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.