User login

An immunization update

As ob.gyns., we pride ourselves on being primary care providers as well as specialists. A central obligation of the primary care physician is the prevention of disease, and immunization of vaccine-preventable diseases is an essential component of prevention. In fact, nothing is more effective at preventing infectious diseases than immunization.

Immunization has not traditionally been as central to our role as it has been for pediatricians, who have long viewed vaccines as a core component of their care. However, although there are certain vaccines that pediatricians can give more easily than we can, such as the human papillomavirus vaccine, there are other vaccines that ob.gyns. can more easily provide. For example, we are better positioned than pediatricians to protect newborns from pertussis.

No other physician, moreover, is better situated to vaccinate vulnerable populations than is the ob.gyn. We are important sources of information and advice for adolescents, adults, and pregnant women. We therefore have a critically important opportunity to identify the diseases that put our patients and their progeny at greatest risk, and a responsibility to make immunization an integral part of our practices.

Numerous investigations and reports addressing vaccine implementation strategies have relevance for both obstetric and gynecologic patients, and studies addressing successful strategies for immunization of pregnant women in particular have increased since the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.

Last spring, the Committee on Obstetric Practice and Committee on Gynecologic Practice of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published guidance on how to successfully incorporate immunizations into routine care and develop an immunization culture (Committee Opinion No. 558, Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:897-903).

Among the key points:

• Make direct recommendations. Talk to your patients directly. Recommend individual immunizations. A provider recommendation has been shown to be one of the strongest influences on patient acceptance. Tell patients, "You should have this vaccine," or "It is important for you," or "I’m telling you as your health care specialist that this vaccine is in your best interest."

Physician scripts for several immunizations are available on ACOG’s immunization website, immunizationforwomen.org, and numerous other sources.

• Designate a vaccine coordinator. As the "vaccine champion," this person orders and receives the vaccines, ensures that the vaccines are stored properly, and has knowledge of appropriate billing codes for vaccination services. He or she also maintains contact with the state health department’s immunization program manager, who can answer physicians’ questions and help practices.

• Institute standing orders. Such orders allow for an indicated vaccine to be administered to patients without an individual physician order. For example, every pregnant woman who shows up during flu season should have a standing order for the influenza vaccination.

Evaluate your prompts, paper or electronic, to remind providers and staff which patients need to be immunized. Hold everyone accountable.

• Get yourself and your staff immunized. Educate staff about the safety and efficacy of immunizations, and ensure that your office health care providers, your entire staff, and you are immunized as recommended. If your staff or you are not immunized, it can be hard to convince patients to receive a vaccine. As ACOG’s Committee Opinion on "Integrating Immunizations into Practice" highlights, moreover, office personnel who express their own uncertainty or lack of knowledge to patients can negatively affect patients’ willingness to receive a vaccine. Additionally, being a potential source of infection for your patients violates ethical obligations.

Research has shown that educational efforts for office staff can markedly increase office immunization rates. In one study of the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009, educational sessions for ob.gyns’ staff were part of a multifaceted approach that led to a high vaccine acceptance rate of 76% in an ethnically diverse population of 157 obstetrics patients (Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;2011:746214 [doi: 10.1155/2011/746214]). The educational sessions for staff were instituted proactively prior to availability of the vaccine.

Influenza vaccination

Influenza affects 10%-20% of the U.S. population annually, and pregnant women are more likely to have serious complications should they contract the virus. Pregnant women are at least 4-5 times more likely to be hospitalized and equally more likely to die from infection, and their infants are more likely to have influenza-related respiratory illnesses and die.

A 2010 study of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic showed that although pregnant women in the United States represent 1%-2% of the population, they accounted for up to 7%-10% of the hospitalized patients, 6%-9% of the ICU patients, and 6%-10% of the patients who died (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010:362:1708-19).

A study published in early 2013 showed that vaccination was 70% successful in preventing 2009 H1N1 influenza infection in pregnant women in Norway during the pandemic, and that the risk of fetal death nearly doubled among women who contracted influenza (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:333-40). Of almost 120,000 pregnant women in the study, approximately half had received the flu vaccine.

Studies of earlier influenza pandemics and large epidemiologic studies of otherwise healthy pregnant women who contracted nonpandemic seasonal influenza have similarly demonstrated how pregnant women and their infants disproportionately experience severe sequelae.

We need to inform our pregnant patients that the influenza vaccine protects their newborns as well as themselves. We must also work harder to dispel misconceptions about the safety of the vaccine.

One barrier to pregnant women receiving the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine was perceived risks to the fetus (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:S124-7). The source of much of this concern stems from the fact that some influenza vaccines contain trace amounts of the preservative thimerosal.

Influenza vaccines that contain a mercury-free preservative are available, but pregnant women should be informed that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Institute of Medicine, and numerous other health organizations have concluded that the thimerosal used in the vaccine is safe. The only flu vaccine that pregnant women should not receive is the attenuated vaccine.

An additional concern for some is that the influenza vaccine contains chicken egg protein, an allergen for some individuals. However, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices now recommends that individuals who have only had hives after exposure to egg should receive the influenza vaccine, though physicians should take extra precautions, such as observing these patients for at least 30 minutes after administering the vaccine (www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).

With influenza immunization, we should celebrate our successes. As described in ACOG’s Committee Opinion on integrating vaccinations, vaccination of pregnant women increased nationwide to a level of approximately 50% in 2009, a significant increase over pre-pandemic rates of approximately 15%. Rates during the 2011-2012 influenza season remained approximately 47%.

Such improvement shows that immunization is achievable in our practices. However, rates hovering around half of all pregnant women are still just slightly north of mediocre. We should continue to make the benefits of vaccination clear to staff and patients, and the algorithm for implementation simple.

Given that the flu season begins in October and can run into spring – and that it takes about 2 weeks for production of protective antibody levels – it is rare that a pregnant woman will not need the vaccine.

Full recommendations for the prevention and control of influenza in 2013-2014 were expected at the time of this writing to be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Tdap

Pertussis is highly infectious, and infants who contract the bacterium have increased rates of whooping cough attacks and are at the greatest risk for severe disease and death. Pertussis outbreaks have become common in the United States, and can be difficult to identify and manage. Infants continue to have the highest reported rates.

When immunization is an integral part of one’s office (with standing orders, etc.), administering a dose of Tdap during each pregnancy to prevent pertussis in infants – as is recommended in the CDC immunization schedule released in January 2013 – should be relatively simple during prenatal office visits.

The postpartum "cocooning" approach recommended by the CDC in 2006 and supported by ACOG has been practically and logistically difficult to implement. While the concept is sound, it has proved too cumbersome overall to vaccinate every family member and caregiver who will have close contact with an infant. Merely having the parents vaccinated immediately postpartum – the other part of cocooning – has been difficult enough.

The new recommendations draw upon the proven paradigm of maternal vaccination for newborn benefit and the relative ease of immunization during prenatal care visits. Ob.gyns. should administer a dose of Tdap during each pregnancy – optimally between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation – irrespective of the patient’s prior history of receiving Tdap.

Infants do not start their vaccination series against these pathogens until age 2 months; maternal immunization in late pregnancy leads to high transplacental antibody transfer, which will protect infants until they receive their own vaccines.

Although the optimal timing for maternal Tdap immunization is later in pregnancy, the vaccine may be given at any time if necessitated by clinical circumstance. For example, if a woman steps on a rusty nail during her first trimester and has not had a tetanus booster in the prior 5 years, or if a local school reports an epidemic, she should receive the Tdap vaccine immediately.

Cocooning is now the default; if Tdap is not administered during pregnancy for some reason, it should be administered immediately postpartum, with as much cocooning as possible.

The challenge with the Tdap vaccine is that few people who live outside areas where pertussis epidemics have occurred know someone who has had the bacterial disease. Education and a direct recommendation for the vaccine are therefore critical.

Human papillomavirus, hepatitis B

HPV vaccines are not recommended for use in pregnant women, and although ob.gyns. are not the central players with these vaccines, we still have an important role to play in HPV immunization. We can help backstop pediatricians and facilitate the recommended "catch-up" for females aged 13-26 years who were not immunized at the recommended starting age of 11 or 12 years.

Unfortunately, the three-dose HPV vaccine series was misframed in the United States as a vaccine to prevent a sexually transmitted infection, rather than being framed, as it was in other countries, as a vaccine to prevent cancer. The unintended consequence has been widespread unwillingness of many U.S. parents to vaccinate their young daughters – a phenomenon that has challenged pediatricians and limited uptake of the vaccine.

For ob.gyns., the catch-up role means that many of their patients who are potential candidates for the vaccines are already sexually active and carrying HPV. Still, ob.gyns. should review the vaccine history with their patients and administer remaining or all doses as needed.

Both of the available vaccines – the quadrivalent HPV vaccine and the bivalent HPV vaccine – protect against viral genotypes 16 and 18, which are associated with 70% of cervical cancers. The quadrivalent vaccine provides extra protection against genotypes 6 and 11, which are associated with 90% of genital warts cases. Both vaccines protect against vulvar, vaginal, anal, and penile dysplasias.

The HPV vaccines have been used broadly throughout the world. In Australia, where vaccine coverage has been high, there is now evidence of herd immunity, with the number of males presenting with new diagnoses of genital warts declining even though females are the ones being vaccinated.

With respect to hepatitis B infection, sexual transmission is the most common mode of transmission in the United States, and in this sense, ob.gyns. have an important opportunity to ensure that women at risk for hepatitis B infection are vaccinated. Ob.gyns. should take a history of a sexually transmitted infection, in particular, as a trigger for action. It should be second nature for us to tell a patient who had gonorrhea 2 years ago that we recommend the hepatitis B vaccine for her.

A history of a sexually transmitted infection is only one of the risk factors for hepatitis B – others include recurrent or current injection drug use, previous incarceration, and exposure to blood products – but it is the one that most clearly calls us into a public health role. A significant number of women who see us during any given year do not see any other physicians or health care providers, so we cannot depend on other providers to take the lead on immunization.

Remember, you cannot always learn of a history of a sexually transmitted infection by simply asking, have you ever had a sexually transmitted infection? Women should be given a list of specific sexually transmitted infections and asked whether they’re ever had any of them. Research has shown that women commonly do not equate pelvic inflammatory disease or Trichomonas vaginalis, for instance, with sexual transmission.

Dr. Minkoff serves as chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Maimonides Medical Center, and is a distinguished professor of obstetrics and gynecology at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, both in Brooklyn, N.Y. Dr. Minkoff reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

As ob.gyns., we pride ourselves on being primary care providers as well as specialists. A central obligation of the primary care physician is the prevention of disease, and immunization of vaccine-preventable diseases is an essential component of prevention. In fact, nothing is more effective at preventing infectious diseases than immunization.

Immunization has not traditionally been as central to our role as it has been for pediatricians, who have long viewed vaccines as a core component of their care. However, although there are certain vaccines that pediatricians can give more easily than we can, such as the human papillomavirus vaccine, there are other vaccines that ob.gyns. can more easily provide. For example, we are better positioned than pediatricians to protect newborns from pertussis.

No other physician, moreover, is better situated to vaccinate vulnerable populations than is the ob.gyn. We are important sources of information and advice for adolescents, adults, and pregnant women. We therefore have a critically important opportunity to identify the diseases that put our patients and their progeny at greatest risk, and a responsibility to make immunization an integral part of our practices.

Numerous investigations and reports addressing vaccine implementation strategies have relevance for both obstetric and gynecologic patients, and studies addressing successful strategies for immunization of pregnant women in particular have increased since the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.

Last spring, the Committee on Obstetric Practice and Committee on Gynecologic Practice of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published guidance on how to successfully incorporate immunizations into routine care and develop an immunization culture (Committee Opinion No. 558, Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:897-903).

Among the key points:

• Make direct recommendations. Talk to your patients directly. Recommend individual immunizations. A provider recommendation has been shown to be one of the strongest influences on patient acceptance. Tell patients, "You should have this vaccine," or "It is important for you," or "I’m telling you as your health care specialist that this vaccine is in your best interest."

Physician scripts for several immunizations are available on ACOG’s immunization website, immunizationforwomen.org, and numerous other sources.

• Designate a vaccine coordinator. As the "vaccine champion," this person orders and receives the vaccines, ensures that the vaccines are stored properly, and has knowledge of appropriate billing codes for vaccination services. He or she also maintains contact with the state health department’s immunization program manager, who can answer physicians’ questions and help practices.

• Institute standing orders. Such orders allow for an indicated vaccine to be administered to patients without an individual physician order. For example, every pregnant woman who shows up during flu season should have a standing order for the influenza vaccination.

Evaluate your prompts, paper or electronic, to remind providers and staff which patients need to be immunized. Hold everyone accountable.

• Get yourself and your staff immunized. Educate staff about the safety and efficacy of immunizations, and ensure that your office health care providers, your entire staff, and you are immunized as recommended. If your staff or you are not immunized, it can be hard to convince patients to receive a vaccine. As ACOG’s Committee Opinion on "Integrating Immunizations into Practice" highlights, moreover, office personnel who express their own uncertainty or lack of knowledge to patients can negatively affect patients’ willingness to receive a vaccine. Additionally, being a potential source of infection for your patients violates ethical obligations.

Research has shown that educational efforts for office staff can markedly increase office immunization rates. In one study of the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009, educational sessions for ob.gyns’ staff were part of a multifaceted approach that led to a high vaccine acceptance rate of 76% in an ethnically diverse population of 157 obstetrics patients (Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;2011:746214 [doi: 10.1155/2011/746214]). The educational sessions for staff were instituted proactively prior to availability of the vaccine.

Influenza vaccination

Influenza affects 10%-20% of the U.S. population annually, and pregnant women are more likely to have serious complications should they contract the virus. Pregnant women are at least 4-5 times more likely to be hospitalized and equally more likely to die from infection, and their infants are more likely to have influenza-related respiratory illnesses and die.

A 2010 study of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic showed that although pregnant women in the United States represent 1%-2% of the population, they accounted for up to 7%-10% of the hospitalized patients, 6%-9% of the ICU patients, and 6%-10% of the patients who died (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010:362:1708-19).

A study published in early 2013 showed that vaccination was 70% successful in preventing 2009 H1N1 influenza infection in pregnant women in Norway during the pandemic, and that the risk of fetal death nearly doubled among women who contracted influenza (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:333-40). Of almost 120,000 pregnant women in the study, approximately half had received the flu vaccine.

Studies of earlier influenza pandemics and large epidemiologic studies of otherwise healthy pregnant women who contracted nonpandemic seasonal influenza have similarly demonstrated how pregnant women and their infants disproportionately experience severe sequelae.

We need to inform our pregnant patients that the influenza vaccine protects their newborns as well as themselves. We must also work harder to dispel misconceptions about the safety of the vaccine.

One barrier to pregnant women receiving the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine was perceived risks to the fetus (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:S124-7). The source of much of this concern stems from the fact that some influenza vaccines contain trace amounts of the preservative thimerosal.

Influenza vaccines that contain a mercury-free preservative are available, but pregnant women should be informed that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Institute of Medicine, and numerous other health organizations have concluded that the thimerosal used in the vaccine is safe. The only flu vaccine that pregnant women should not receive is the attenuated vaccine.

An additional concern for some is that the influenza vaccine contains chicken egg protein, an allergen for some individuals. However, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices now recommends that individuals who have only had hives after exposure to egg should receive the influenza vaccine, though physicians should take extra precautions, such as observing these patients for at least 30 minutes after administering the vaccine (www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).

With influenza immunization, we should celebrate our successes. As described in ACOG’s Committee Opinion on integrating vaccinations, vaccination of pregnant women increased nationwide to a level of approximately 50% in 2009, a significant increase over pre-pandemic rates of approximately 15%. Rates during the 2011-2012 influenza season remained approximately 47%.

Such improvement shows that immunization is achievable in our practices. However, rates hovering around half of all pregnant women are still just slightly north of mediocre. We should continue to make the benefits of vaccination clear to staff and patients, and the algorithm for implementation simple.

Given that the flu season begins in October and can run into spring – and that it takes about 2 weeks for production of protective antibody levels – it is rare that a pregnant woman will not need the vaccine.

Full recommendations for the prevention and control of influenza in 2013-2014 were expected at the time of this writing to be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Tdap

Pertussis is highly infectious, and infants who contract the bacterium have increased rates of whooping cough attacks and are at the greatest risk for severe disease and death. Pertussis outbreaks have become common in the United States, and can be difficult to identify and manage. Infants continue to have the highest reported rates.

When immunization is an integral part of one’s office (with standing orders, etc.), administering a dose of Tdap during each pregnancy to prevent pertussis in infants – as is recommended in the CDC immunization schedule released in January 2013 – should be relatively simple during prenatal office visits.

The postpartum "cocooning" approach recommended by the CDC in 2006 and supported by ACOG has been practically and logistically difficult to implement. While the concept is sound, it has proved too cumbersome overall to vaccinate every family member and caregiver who will have close contact with an infant. Merely having the parents vaccinated immediately postpartum – the other part of cocooning – has been difficult enough.

The new recommendations draw upon the proven paradigm of maternal vaccination for newborn benefit and the relative ease of immunization during prenatal care visits. Ob.gyns. should administer a dose of Tdap during each pregnancy – optimally between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation – irrespective of the patient’s prior history of receiving Tdap.

Infants do not start their vaccination series against these pathogens until age 2 months; maternal immunization in late pregnancy leads to high transplacental antibody transfer, which will protect infants until they receive their own vaccines.

Although the optimal timing for maternal Tdap immunization is later in pregnancy, the vaccine may be given at any time if necessitated by clinical circumstance. For example, if a woman steps on a rusty nail during her first trimester and has not had a tetanus booster in the prior 5 years, or if a local school reports an epidemic, she should receive the Tdap vaccine immediately.

Cocooning is now the default; if Tdap is not administered during pregnancy for some reason, it should be administered immediately postpartum, with as much cocooning as possible.

The challenge with the Tdap vaccine is that few people who live outside areas where pertussis epidemics have occurred know someone who has had the bacterial disease. Education and a direct recommendation for the vaccine are therefore critical.

Human papillomavirus, hepatitis B

HPV vaccines are not recommended for use in pregnant women, and although ob.gyns. are not the central players with these vaccines, we still have an important role to play in HPV immunization. We can help backstop pediatricians and facilitate the recommended "catch-up" for females aged 13-26 years who were not immunized at the recommended starting age of 11 or 12 years.

Unfortunately, the three-dose HPV vaccine series was misframed in the United States as a vaccine to prevent a sexually transmitted infection, rather than being framed, as it was in other countries, as a vaccine to prevent cancer. The unintended consequence has been widespread unwillingness of many U.S. parents to vaccinate their young daughters – a phenomenon that has challenged pediatricians and limited uptake of the vaccine.

For ob.gyns., the catch-up role means that many of their patients who are potential candidates for the vaccines are already sexually active and carrying HPV. Still, ob.gyns. should review the vaccine history with their patients and administer remaining or all doses as needed.

Both of the available vaccines – the quadrivalent HPV vaccine and the bivalent HPV vaccine – protect against viral genotypes 16 and 18, which are associated with 70% of cervical cancers. The quadrivalent vaccine provides extra protection against genotypes 6 and 11, which are associated with 90% of genital warts cases. Both vaccines protect against vulvar, vaginal, anal, and penile dysplasias.

The HPV vaccines have been used broadly throughout the world. In Australia, where vaccine coverage has been high, there is now evidence of herd immunity, with the number of males presenting with new diagnoses of genital warts declining even though females are the ones being vaccinated.

With respect to hepatitis B infection, sexual transmission is the most common mode of transmission in the United States, and in this sense, ob.gyns. have an important opportunity to ensure that women at risk for hepatitis B infection are vaccinated. Ob.gyns. should take a history of a sexually transmitted infection, in particular, as a trigger for action. It should be second nature for us to tell a patient who had gonorrhea 2 years ago that we recommend the hepatitis B vaccine for her.

A history of a sexually transmitted infection is only one of the risk factors for hepatitis B – others include recurrent or current injection drug use, previous incarceration, and exposure to blood products – but it is the one that most clearly calls us into a public health role. A significant number of women who see us during any given year do not see any other physicians or health care providers, so we cannot depend on other providers to take the lead on immunization.

Remember, you cannot always learn of a history of a sexually transmitted infection by simply asking, have you ever had a sexually transmitted infection? Women should be given a list of specific sexually transmitted infections and asked whether they’re ever had any of them. Research has shown that women commonly do not equate pelvic inflammatory disease or Trichomonas vaginalis, for instance, with sexual transmission.

Dr. Minkoff serves as chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Maimonides Medical Center, and is a distinguished professor of obstetrics and gynecology at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, both in Brooklyn, N.Y. Dr. Minkoff reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

As ob.gyns., we pride ourselves on being primary care providers as well as specialists. A central obligation of the primary care physician is the prevention of disease, and immunization of vaccine-preventable diseases is an essential component of prevention. In fact, nothing is more effective at preventing infectious diseases than immunization.

Immunization has not traditionally been as central to our role as it has been for pediatricians, who have long viewed vaccines as a core component of their care. However, although there are certain vaccines that pediatricians can give more easily than we can, such as the human papillomavirus vaccine, there are other vaccines that ob.gyns. can more easily provide. For example, we are better positioned than pediatricians to protect newborns from pertussis.

No other physician, moreover, is better situated to vaccinate vulnerable populations than is the ob.gyn. We are important sources of information and advice for adolescents, adults, and pregnant women. We therefore have a critically important opportunity to identify the diseases that put our patients and their progeny at greatest risk, and a responsibility to make immunization an integral part of our practices.

Numerous investigations and reports addressing vaccine implementation strategies have relevance for both obstetric and gynecologic patients, and studies addressing successful strategies for immunization of pregnant women in particular have increased since the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.

Last spring, the Committee on Obstetric Practice and Committee on Gynecologic Practice of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published guidance on how to successfully incorporate immunizations into routine care and develop an immunization culture (Committee Opinion No. 558, Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:897-903).

Among the key points:

• Make direct recommendations. Talk to your patients directly. Recommend individual immunizations. A provider recommendation has been shown to be one of the strongest influences on patient acceptance. Tell patients, "You should have this vaccine," or "It is important for you," or "I’m telling you as your health care specialist that this vaccine is in your best interest."

Physician scripts for several immunizations are available on ACOG’s immunization website, immunizationforwomen.org, and numerous other sources.

• Designate a vaccine coordinator. As the "vaccine champion," this person orders and receives the vaccines, ensures that the vaccines are stored properly, and has knowledge of appropriate billing codes for vaccination services. He or she also maintains contact with the state health department’s immunization program manager, who can answer physicians’ questions and help practices.

• Institute standing orders. Such orders allow for an indicated vaccine to be administered to patients without an individual physician order. For example, every pregnant woman who shows up during flu season should have a standing order for the influenza vaccination.

Evaluate your prompts, paper or electronic, to remind providers and staff which patients need to be immunized. Hold everyone accountable.

• Get yourself and your staff immunized. Educate staff about the safety and efficacy of immunizations, and ensure that your office health care providers, your entire staff, and you are immunized as recommended. If your staff or you are not immunized, it can be hard to convince patients to receive a vaccine. As ACOG’s Committee Opinion on "Integrating Immunizations into Practice" highlights, moreover, office personnel who express their own uncertainty or lack of knowledge to patients can negatively affect patients’ willingness to receive a vaccine. Additionally, being a potential source of infection for your patients violates ethical obligations.

Research has shown that educational efforts for office staff can markedly increase office immunization rates. In one study of the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009, educational sessions for ob.gyns’ staff were part of a multifaceted approach that led to a high vaccine acceptance rate of 76% in an ethnically diverse population of 157 obstetrics patients (Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;2011:746214 [doi: 10.1155/2011/746214]). The educational sessions for staff were instituted proactively prior to availability of the vaccine.

Influenza vaccination

Influenza affects 10%-20% of the U.S. population annually, and pregnant women are more likely to have serious complications should they contract the virus. Pregnant women are at least 4-5 times more likely to be hospitalized and equally more likely to die from infection, and their infants are more likely to have influenza-related respiratory illnesses and die.

A 2010 study of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic showed that although pregnant women in the United States represent 1%-2% of the population, they accounted for up to 7%-10% of the hospitalized patients, 6%-9% of the ICU patients, and 6%-10% of the patients who died (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010:362:1708-19).

A study published in early 2013 showed that vaccination was 70% successful in preventing 2009 H1N1 influenza infection in pregnant women in Norway during the pandemic, and that the risk of fetal death nearly doubled among women who contracted influenza (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:333-40). Of almost 120,000 pregnant women in the study, approximately half had received the flu vaccine.

Studies of earlier influenza pandemics and large epidemiologic studies of otherwise healthy pregnant women who contracted nonpandemic seasonal influenza have similarly demonstrated how pregnant women and their infants disproportionately experience severe sequelae.

We need to inform our pregnant patients that the influenza vaccine protects their newborns as well as themselves. We must also work harder to dispel misconceptions about the safety of the vaccine.

One barrier to pregnant women receiving the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine was perceived risks to the fetus (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:S124-7). The source of much of this concern stems from the fact that some influenza vaccines contain trace amounts of the preservative thimerosal.

Influenza vaccines that contain a mercury-free preservative are available, but pregnant women should be informed that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Institute of Medicine, and numerous other health organizations have concluded that the thimerosal used in the vaccine is safe. The only flu vaccine that pregnant women should not receive is the attenuated vaccine.

An additional concern for some is that the influenza vaccine contains chicken egg protein, an allergen for some individuals. However, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices now recommends that individuals who have only had hives after exposure to egg should receive the influenza vaccine, though physicians should take extra precautions, such as observing these patients for at least 30 minutes after administering the vaccine (www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).

With influenza immunization, we should celebrate our successes. As described in ACOG’s Committee Opinion on integrating vaccinations, vaccination of pregnant women increased nationwide to a level of approximately 50% in 2009, a significant increase over pre-pandemic rates of approximately 15%. Rates during the 2011-2012 influenza season remained approximately 47%.

Such improvement shows that immunization is achievable in our practices. However, rates hovering around half of all pregnant women are still just slightly north of mediocre. We should continue to make the benefits of vaccination clear to staff and patients, and the algorithm for implementation simple.

Given that the flu season begins in October and can run into spring – and that it takes about 2 weeks for production of protective antibody levels – it is rare that a pregnant woman will not need the vaccine.

Full recommendations for the prevention and control of influenza in 2013-2014 were expected at the time of this writing to be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Tdap

Pertussis is highly infectious, and infants who contract the bacterium have increased rates of whooping cough attacks and are at the greatest risk for severe disease and death. Pertussis outbreaks have become common in the United States, and can be difficult to identify and manage. Infants continue to have the highest reported rates.

When immunization is an integral part of one’s office (with standing orders, etc.), administering a dose of Tdap during each pregnancy to prevent pertussis in infants – as is recommended in the CDC immunization schedule released in January 2013 – should be relatively simple during prenatal office visits.

The postpartum "cocooning" approach recommended by the CDC in 2006 and supported by ACOG has been practically and logistically difficult to implement. While the concept is sound, it has proved too cumbersome overall to vaccinate every family member and caregiver who will have close contact with an infant. Merely having the parents vaccinated immediately postpartum – the other part of cocooning – has been difficult enough.

The new recommendations draw upon the proven paradigm of maternal vaccination for newborn benefit and the relative ease of immunization during prenatal care visits. Ob.gyns. should administer a dose of Tdap during each pregnancy – optimally between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation – irrespective of the patient’s prior history of receiving Tdap.

Infants do not start their vaccination series against these pathogens until age 2 months; maternal immunization in late pregnancy leads to high transplacental antibody transfer, which will protect infants until they receive their own vaccines.

Although the optimal timing for maternal Tdap immunization is later in pregnancy, the vaccine may be given at any time if necessitated by clinical circumstance. For example, if a woman steps on a rusty nail during her first trimester and has not had a tetanus booster in the prior 5 years, or if a local school reports an epidemic, she should receive the Tdap vaccine immediately.

Cocooning is now the default; if Tdap is not administered during pregnancy for some reason, it should be administered immediately postpartum, with as much cocooning as possible.

The challenge with the Tdap vaccine is that few people who live outside areas where pertussis epidemics have occurred know someone who has had the bacterial disease. Education and a direct recommendation for the vaccine are therefore critical.

Human papillomavirus, hepatitis B

HPV vaccines are not recommended for use in pregnant women, and although ob.gyns. are not the central players with these vaccines, we still have an important role to play in HPV immunization. We can help backstop pediatricians and facilitate the recommended "catch-up" for females aged 13-26 years who were not immunized at the recommended starting age of 11 or 12 years.

Unfortunately, the three-dose HPV vaccine series was misframed in the United States as a vaccine to prevent a sexually transmitted infection, rather than being framed, as it was in other countries, as a vaccine to prevent cancer. The unintended consequence has been widespread unwillingness of many U.S. parents to vaccinate their young daughters – a phenomenon that has challenged pediatricians and limited uptake of the vaccine.

For ob.gyns., the catch-up role means that many of their patients who are potential candidates for the vaccines are already sexually active and carrying HPV. Still, ob.gyns. should review the vaccine history with their patients and administer remaining or all doses as needed.

Both of the available vaccines – the quadrivalent HPV vaccine and the bivalent HPV vaccine – protect against viral genotypes 16 and 18, which are associated with 70% of cervical cancers. The quadrivalent vaccine provides extra protection against genotypes 6 and 11, which are associated with 90% of genital warts cases. Both vaccines protect against vulvar, vaginal, anal, and penile dysplasias.

The HPV vaccines have been used broadly throughout the world. In Australia, where vaccine coverage has been high, there is now evidence of herd immunity, with the number of males presenting with new diagnoses of genital warts declining even though females are the ones being vaccinated.

With respect to hepatitis B infection, sexual transmission is the most common mode of transmission in the United States, and in this sense, ob.gyns. have an important opportunity to ensure that women at risk for hepatitis B infection are vaccinated. Ob.gyns. should take a history of a sexually transmitted infection, in particular, as a trigger for action. It should be second nature for us to tell a patient who had gonorrhea 2 years ago that we recommend the hepatitis B vaccine for her.

A history of a sexually transmitted infection is only one of the risk factors for hepatitis B – others include recurrent or current injection drug use, previous incarceration, and exposure to blood products – but it is the one that most clearly calls us into a public health role. A significant number of women who see us during any given year do not see any other physicians or health care providers, so we cannot depend on other providers to take the lead on immunization.

Remember, you cannot always learn of a history of a sexually transmitted infection by simply asking, have you ever had a sexually transmitted infection? Women should be given a list of specific sexually transmitted infections and asked whether they’re ever had any of them. Research has shown that women commonly do not equate pelvic inflammatory disease or Trichomonas vaginalis, for instance, with sexual transmission.

Dr. Minkoff serves as chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Maimonides Medical Center, and is a distinguished professor of obstetrics and gynecology at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, both in Brooklyn, N.Y. Dr. Minkoff reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

HIV in Pregnancy: An Update

Remarkable progress has been made over the past 30-plus years in the identification of the human immunodeficiency virus, in the development of drugs to treat HIV infection, and in providing access and assuring adherence to these increasingly effective therapies. As a result, we can now offer women with HIV infection a significantly improved prognosis as well as a very high likelihood of having children who will not be infected with HIV.

While HIV infection is still an incurable, lifelong disease, it has in many ways become a chronic disease just like many other chronic diseases – a status that just a generation ago would have been a pipe dream. Today when I see a patient who has hypertension, diabetes, and HIV infection, I am often more worried about managing the hypertension and diabetes than I am about managing the HIV.

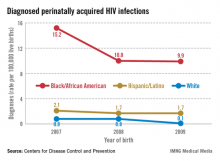

In my state of New York, for example, the number of babies born with HIV infection 15 years ago was approximately 100; in 2010, this number was 3.

Whether we practice in an area of high or low prevalence, we each have a responsibility to identify HIV-infected women and, in the context of pregnancy, to ensure that each patient’s prognosis is optimized, and perinatal transmission is prevented by bringing her viral load to an undetectable level. In cases in which an uninfected woman is considering pregnancy and her partner is HIV infected, periconception administration of antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis is a new and promising tool.

Identifying patients

None of these benefits can be provided to HIV-infected women if their status is unknown. Just as we have to measure blood pressure in order to be able to treat hypertension, we must ensure that women in our practices know their HIV status so that they can avail themselves of the remarkable advances that have been made in the care of HIV infection and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Testing appropriately is part of our role.

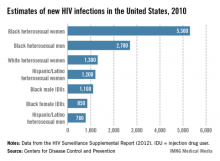

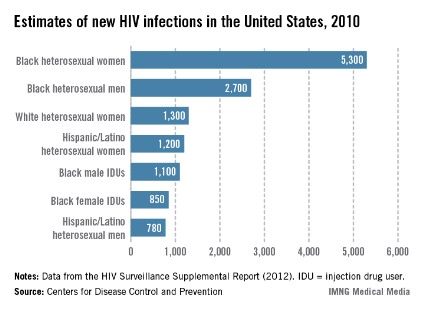

Certainly, HIV incidence and risk for infection vary across the United States; there are dramatic differences in risk, for instance, between Des Moines, where prevalence is low, and Washington, D.C., where almost 3% of the population is infected with HIV. Still, regardless of geography, we must appreciate that the impact of the epidemic on women has grown significantly over time, such that women now account for approximately one in four people living with HIV, according to the CDC.

What is especially important for us to appreciate is the fact that a sizable portion of all people with HIV still do not know their HIV status. The CDC estimates that approximately 18% of all HIV-infected individuals are unaware of their status.

A significant percentage of the children who are infected, moreover, were born to women whose status was unknown. According to the CDC, approximately 27% of the mothers of HIV-infected infants reported from 2003 to 2007 were diagnosed with HIV after delivery, and only 29% of the mothers of infected infants received antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy.

The CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other national organizations have long called for universal prenatal HIV testing to improve the health outcomes of the mother and infant.

On a broader level, the approach to testing has evolved. In 2006, the CDC moved away from targeted risk-based HIV testing recommendations and advised routine opt-out testing for all patients aged 13-64 years. The agency concluded that universal testing is more effective largely because many patients found to be infected did not consider themselves to be at risk. ACOG weighed in the following year, also recommending universal testing with patient notification and an opt-out option, which removes the need for detailed, testing-related informed consent.

Some state laws do not allow opt-out testing and still require affirmative consent, however, so it is important to know your state’s laws. Regardless of your state’s situation, however, failing to test because you deem a patient unlikely to be infected is no longer acceptable.

Testing should be approached just as a blood pressure check is approached – as part of a routine battery of tests that is performed unless the patient declines.

Although the adverse consequences of being identified as HIV positive remain to some extent, it is by no means as severe as it was in the 1980s, when women with positive test results were stigmatized and discriminated against. As primary care providers, we should be reassuring in this regard and much more assertive in making sure patients understand the benefits of testing.

In a related move this year, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is recommending that all patients aged 15-65 years should be screened for HIV, regardless of their risk level.

Treating infection

Strategies for preventing perinatal transmission and managing HIV disease in pregnancy are evolving so rapidly that it is often best for obstetricians who see only a few HIV-infected patients a year to work in consultation with an obstetrician with expertise in HIV in pregnancy, an infectious disease specialist or HIV specialty care provider, or an internist with expert knowledge of the antiretroviral drugs. The National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women, last updated in July 2012, can be a useful reference.

The latest generation of ARV drugs are not only more effective, but also many require only once-a-day dosing schedules, which can improve patient adherence. On the flip side, there are dozens of choices for individualizing treatment, making treatment decisions much more complex than a decade ago.

Among the important trends and changes for ob.gyns to be aware of are the following:

• A "test and treat" paradigm. We are entering a "test and treat" era in the treatment of HIV infection overall, with the paradigm shifting to a much more liberal and immediate recourse to therapy for HIV-infected adults.

Previously, regular monitoring of virologic status would help guide the timing of therapy initiation. For example, CD4 T-lymphocyte counts of less than 350 mm3 or plasma HIV RNA levels that exceeded certain thresholds were the recommended triggers for initiation of ARV therapy. Although there remains some disagreement among experts who support treating a patient when CD4 counts reach 550 mm3 and experts who support treating a patient regardless of CD4 or viral load, I believe the scale is tipping toward treating almost everyone upon diagnosis. Waiting until patients have become more immunocompromised and reached a chronic infection–induced inflammatory state can drive the development of cardiovascular disease and other long-term health care problems.

While some debate persists as to whether all HIV-infected individuals should begin treatment regardless of CD4 count, there is no question as to the appropriate approach for the pregnant woman.

For HIV-infected pregnant women, it is currently recommended that a combination ARV drug regimen be implemented as early as possible antepartum to prevent perinatal transmission, regardless of HIV RNA copy number or CD4 T-lymphocyte count. Evidence that transmission may be lowered with earlier initiation of ART, combined with growing evidence regarding the safety of ARV drugs, has shifted the mindset from a paradigm of avoiding therapy in the first trimester unless absolutely necessary, to a slightly more aggressive approach with earlier initiation of ARV drugs.

Women who enter pregnancy on an effective ARV regimen should continue this regimen without disruption, as drugs changes during pregnancy may be associated with loss of viral control and increased risk of perinatal transmission.

• Lessening concern about risks. Certainly, the known benefits of ARV drugs for a pregnant woman must be weighed against the potential risks of adverse events to the woman, fetus, and newborn. The NIH clinical guidelines categorize various antiretroviral agents for use in pregnancy as preferred, alternative, or for "use in special circumstances."

In general, however, we have acquired more information on the safety of many of these drugs in pregnancy. As data have accumulated, concerns about potential teratogenic effects and other adverse effects of ARV drugs on fetuses and newborns have lessened.

For example, long-standing concerns about tenofovir decreasing fetal bone porosity and potentially causing other anomalies have lessened with recent studies suggesting that adverse events from tenofovir occur infrequently. The use of other drugs, such as efavirenz, also has been liberalized with recent evidence showing that the risk of adverse events is much lower than once believed; recent guidelines now advise that efavirenz rarely needs to be discontinued among women who were receiving it prior to pregnancy.

Obstetricians’ chief role in working with consultants is to ensure that a less-effective drug is not prescribed merely because a patient is pregnant. An effective Class C drug should not be replaced by an ineffective Class B drug solely because an internist does not understand drug use in pregnancy. Obstetricians understand that risks of drugs must be balanced against the risks of untreated diseases.

We sometimes prescribe antiseizure drugs and other category D medications during pregnancy when the benefits outweigh the risks, and preventing HIV transmission from mother to fetus is no different. Suppressing the virus is the primary goal in HIV treatment today, and pregnancy should not preclude the use of therapeutics that can attain that goal.

• New intrapartum approach. Probably the most significant recent change to the NIH guidelines concerns the use of intravenous zidovudine (AZT) during labor in women infected with HIV.

Parenteral AZT had been the standard of care since 1994; however, the 2012 guidelines state that AZT is no longer required during labor for HIV-infected women who are receiving combination antiretroviral regimens and who have an undetectable viral load (HIV RNA less than 400 copies/mL near delivery). Studies have shown that with these two criteria met, the transmission rate is low enough that there is no reason to believe that AZT would provide any additional benefit.

Utilizing the Ob. skill set

The choice of drug regiments for HIV-infected pregnant women should be based on the same principles used to choose regimens for nonpregnant individuals, and it is the obstetrician’s job – not the job of the internist or other expert – to decide whether there are compelling pregnancy-specific reasons that should cause modifications.

When there is concern about an elevated risk of preterm birth, as there is with the use of protease inhibitors in the first trimester, obstetricians can utilize cervical length screening and/or appropriate techniques and approaches for monitoring patients, just as they would monitor other patients with elevated risk.

Obstetricians also can also bring their expertise and knowledge of current obstetrical technologies to the table when it comes to the use of amniocentesis in HIV-infected pregnant women. The risks of amniocentesis are minimal (no perinatal transmissions have been reported after amniocentesis in women without detectable virus and on effective ART), but any small potential or perceived risk can be further reduced by using new tests that allow a determination of the likelihood of chromosomal abnormalities through peripheral blood sampling. If a patient’s peripheral blood status is indicative of lower-than-expected risks of aneuploidy, for instance, the patient may decide she can forego amniocentesis.

Additionally, the field of safe reproduction for HIV-discordant couples is progressing. Data from the NIH-supported HPTN 052 randomized clinical trial show that early initiation of ART in the infected partner significantly reduces HIV transmission to the uninfected partner.

Although not as well studied, periconception administration of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-uninfected partners may offer an additional tool for reducing the risk of sexual transmission. (The NIH guidelines for use of ARV drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women include a section on "Reproductive Options of HIV-Concordant and Serodiscordant Couples.")

Uninfected women should be regularly counseled about consistent condom use, but especially in cases in which couples are opposed to protected intercourse and the use of assisted reproductive techniques (sperm preparation techniques coupled with either intrauterine insemination or in vitro fertilization), the use of antiretroviral medications by uninfected women may provide for safer conception.

Dr. Minkoff serves as chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Maimonides Medical Center in New York and is a distinguished professor of obstetrics and gynecology at State University of New York–Health Science Center. Hef has published extensively on HIV detection and treatment and has been involved over the years on numerous panels, task forces, and guideline committees dealing with the care of HIV-infected women. He currently serves on the panel for the National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women.

Dr. Minkoff reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Remarkable progress has been made over the past 30-plus years in the identification of the human immunodeficiency virus, in the development of drugs to treat HIV infection, and in providing access and assuring adherence to these increasingly effective therapies. As a result, we can now offer women with HIV infection a significantly improved prognosis as well as a very high likelihood of having children who will not be infected with HIV.

While HIV infection is still an incurable, lifelong disease, it has in many ways become a chronic disease just like many other chronic diseases – a status that just a generation ago would have been a pipe dream. Today when I see a patient who has hypertension, diabetes, and HIV infection, I am often more worried about managing the hypertension and diabetes than I am about managing the HIV.

In my state of New York, for example, the number of babies born with HIV infection 15 years ago was approximately 100; in 2010, this number was 3.

Whether we practice in an area of high or low prevalence, we each have a responsibility to identify HIV-infected women and, in the context of pregnancy, to ensure that each patient’s prognosis is optimized, and perinatal transmission is prevented by bringing her viral load to an undetectable level. In cases in which an uninfected woman is considering pregnancy and her partner is HIV infected, periconception administration of antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis is a new and promising tool.

Identifying patients

None of these benefits can be provided to HIV-infected women if their status is unknown. Just as we have to measure blood pressure in order to be able to treat hypertension, we must ensure that women in our practices know their HIV status so that they can avail themselves of the remarkable advances that have been made in the care of HIV infection and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Testing appropriately is part of our role.

Certainly, HIV incidence and risk for infection vary across the United States; there are dramatic differences in risk, for instance, between Des Moines, where prevalence is low, and Washington, D.C., where almost 3% of the population is infected with HIV. Still, regardless of geography, we must appreciate that the impact of the epidemic on women has grown significantly over time, such that women now account for approximately one in four people living with HIV, according to the CDC.

What is especially important for us to appreciate is the fact that a sizable portion of all people with HIV still do not know their HIV status. The CDC estimates that approximately 18% of all HIV-infected individuals are unaware of their status.

A significant percentage of the children who are infected, moreover, were born to women whose status was unknown. According to the CDC, approximately 27% of the mothers of HIV-infected infants reported from 2003 to 2007 were diagnosed with HIV after delivery, and only 29% of the mothers of infected infants received antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy.

The CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other national organizations have long called for universal prenatal HIV testing to improve the health outcomes of the mother and infant.

On a broader level, the approach to testing has evolved. In 2006, the CDC moved away from targeted risk-based HIV testing recommendations and advised routine opt-out testing for all patients aged 13-64 years. The agency concluded that universal testing is more effective largely because many patients found to be infected did not consider themselves to be at risk. ACOG weighed in the following year, also recommending universal testing with patient notification and an opt-out option, which removes the need for detailed, testing-related informed consent.

Some state laws do not allow opt-out testing and still require affirmative consent, however, so it is important to know your state’s laws. Regardless of your state’s situation, however, failing to test because you deem a patient unlikely to be infected is no longer acceptable.

Testing should be approached just as a blood pressure check is approached – as part of a routine battery of tests that is performed unless the patient declines.

Although the adverse consequences of being identified as HIV positive remain to some extent, it is by no means as severe as it was in the 1980s, when women with positive test results were stigmatized and discriminated against. As primary care providers, we should be reassuring in this regard and much more assertive in making sure patients understand the benefits of testing.

In a related move this year, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is recommending that all patients aged 15-65 years should be screened for HIV, regardless of their risk level.

Treating infection

Strategies for preventing perinatal transmission and managing HIV disease in pregnancy are evolving so rapidly that it is often best for obstetricians who see only a few HIV-infected patients a year to work in consultation with an obstetrician with expertise in HIV in pregnancy, an infectious disease specialist or HIV specialty care provider, or an internist with expert knowledge of the antiretroviral drugs. The National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women, last updated in July 2012, can be a useful reference.

The latest generation of ARV drugs are not only more effective, but also many require only once-a-day dosing schedules, which can improve patient adherence. On the flip side, there are dozens of choices for individualizing treatment, making treatment decisions much more complex than a decade ago.

Among the important trends and changes for ob.gyns to be aware of are the following:

• A "test and treat" paradigm. We are entering a "test and treat" era in the treatment of HIV infection overall, with the paradigm shifting to a much more liberal and immediate recourse to therapy for HIV-infected adults.

Previously, regular monitoring of virologic status would help guide the timing of therapy initiation. For example, CD4 T-lymphocyte counts of less than 350 mm3 or plasma HIV RNA levels that exceeded certain thresholds were the recommended triggers for initiation of ARV therapy. Although there remains some disagreement among experts who support treating a patient when CD4 counts reach 550 mm3 and experts who support treating a patient regardless of CD4 or viral load, I believe the scale is tipping toward treating almost everyone upon diagnosis. Waiting until patients have become more immunocompromised and reached a chronic infection–induced inflammatory state can drive the development of cardiovascular disease and other long-term health care problems.

While some debate persists as to whether all HIV-infected individuals should begin treatment regardless of CD4 count, there is no question as to the appropriate approach for the pregnant woman.

For HIV-infected pregnant women, it is currently recommended that a combination ARV drug regimen be implemented as early as possible antepartum to prevent perinatal transmission, regardless of HIV RNA copy number or CD4 T-lymphocyte count. Evidence that transmission may be lowered with earlier initiation of ART, combined with growing evidence regarding the safety of ARV drugs, has shifted the mindset from a paradigm of avoiding therapy in the first trimester unless absolutely necessary, to a slightly more aggressive approach with earlier initiation of ARV drugs.

Women who enter pregnancy on an effective ARV regimen should continue this regimen without disruption, as drugs changes during pregnancy may be associated with loss of viral control and increased risk of perinatal transmission.

• Lessening concern about risks. Certainly, the known benefits of ARV drugs for a pregnant woman must be weighed against the potential risks of adverse events to the woman, fetus, and newborn. The NIH clinical guidelines categorize various antiretroviral agents for use in pregnancy as preferred, alternative, or for "use in special circumstances."

In general, however, we have acquired more information on the safety of many of these drugs in pregnancy. As data have accumulated, concerns about potential teratogenic effects and other adverse effects of ARV drugs on fetuses and newborns have lessened.

For example, long-standing concerns about tenofovir decreasing fetal bone porosity and potentially causing other anomalies have lessened with recent studies suggesting that adverse events from tenofovir occur infrequently. The use of other drugs, such as efavirenz, also has been liberalized with recent evidence showing that the risk of adverse events is much lower than once believed; recent guidelines now advise that efavirenz rarely needs to be discontinued among women who were receiving it prior to pregnancy.

Obstetricians’ chief role in working with consultants is to ensure that a less-effective drug is not prescribed merely because a patient is pregnant. An effective Class C drug should not be replaced by an ineffective Class B drug solely because an internist does not understand drug use in pregnancy. Obstetricians understand that risks of drugs must be balanced against the risks of untreated diseases.

We sometimes prescribe antiseizure drugs and other category D medications during pregnancy when the benefits outweigh the risks, and preventing HIV transmission from mother to fetus is no different. Suppressing the virus is the primary goal in HIV treatment today, and pregnancy should not preclude the use of therapeutics that can attain that goal.

• New intrapartum approach. Probably the most significant recent change to the NIH guidelines concerns the use of intravenous zidovudine (AZT) during labor in women infected with HIV.

Parenteral AZT had been the standard of care since 1994; however, the 2012 guidelines state that AZT is no longer required during labor for HIV-infected women who are receiving combination antiretroviral regimens and who have an undetectable viral load (HIV RNA less than 400 copies/mL near delivery). Studies have shown that with these two criteria met, the transmission rate is low enough that there is no reason to believe that AZT would provide any additional benefit.

Utilizing the Ob. skill set

The choice of drug regiments for HIV-infected pregnant women should be based on the same principles used to choose regimens for nonpregnant individuals, and it is the obstetrician’s job – not the job of the internist or other expert – to decide whether there are compelling pregnancy-specific reasons that should cause modifications.

When there is concern about an elevated risk of preterm birth, as there is with the use of protease inhibitors in the first trimester, obstetricians can utilize cervical length screening and/or appropriate techniques and approaches for monitoring patients, just as they would monitor other patients with elevated risk.

Obstetricians also can also bring their expertise and knowledge of current obstetrical technologies to the table when it comes to the use of amniocentesis in HIV-infected pregnant women. The risks of amniocentesis are minimal (no perinatal transmissions have been reported after amniocentesis in women without detectable virus and on effective ART), but any small potential or perceived risk can be further reduced by using new tests that allow a determination of the likelihood of chromosomal abnormalities through peripheral blood sampling. If a patient’s peripheral blood status is indicative of lower-than-expected risks of aneuploidy, for instance, the patient may decide she can forego amniocentesis.

Additionally, the field of safe reproduction for HIV-discordant couples is progressing. Data from the NIH-supported HPTN 052 randomized clinical trial show that early initiation of ART in the infected partner significantly reduces HIV transmission to the uninfected partner.

Although not as well studied, periconception administration of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-uninfected partners may offer an additional tool for reducing the risk of sexual transmission. (The NIH guidelines for use of ARV drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women include a section on "Reproductive Options of HIV-Concordant and Serodiscordant Couples.")

Uninfected women should be regularly counseled about consistent condom use, but especially in cases in which couples are opposed to protected intercourse and the use of assisted reproductive techniques (sperm preparation techniques coupled with either intrauterine insemination or in vitro fertilization), the use of antiretroviral medications by uninfected women may provide for safer conception.

Dr. Minkoff serves as chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Maimonides Medical Center in New York and is a distinguished professor of obstetrics and gynecology at State University of New York–Health Science Center. Hef has published extensively on HIV detection and treatment and has been involved over the years on numerous panels, task forces, and guideline committees dealing with the care of HIV-infected women. He currently serves on the panel for the National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women.

Dr. Minkoff reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Remarkable progress has been made over the past 30-plus years in the identification of the human immunodeficiency virus, in the development of drugs to treat HIV infection, and in providing access and assuring adherence to these increasingly effective therapies. As a result, we can now offer women with HIV infection a significantly improved prognosis as well as a very high likelihood of having children who will not be infected with HIV.

While HIV infection is still an incurable, lifelong disease, it has in many ways become a chronic disease just like many other chronic diseases – a status that just a generation ago would have been a pipe dream. Today when I see a patient who has hypertension, diabetes, and HIV infection, I am often more worried about managing the hypertension and diabetes than I am about managing the HIV.

In my state of New York, for example, the number of babies born with HIV infection 15 years ago was approximately 100; in 2010, this number was 3.

Whether we practice in an area of high or low prevalence, we each have a responsibility to identify HIV-infected women and, in the context of pregnancy, to ensure that each patient’s prognosis is optimized, and perinatal transmission is prevented by bringing her viral load to an undetectable level. In cases in which an uninfected woman is considering pregnancy and her partner is HIV infected, periconception administration of antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis is a new and promising tool.

Identifying patients

None of these benefits can be provided to HIV-infected women if their status is unknown. Just as we have to measure blood pressure in order to be able to treat hypertension, we must ensure that women in our practices know their HIV status so that they can avail themselves of the remarkable advances that have been made in the care of HIV infection and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Testing appropriately is part of our role.

Certainly, HIV incidence and risk for infection vary across the United States; there are dramatic differences in risk, for instance, between Des Moines, where prevalence is low, and Washington, D.C., where almost 3% of the population is infected with HIV. Still, regardless of geography, we must appreciate that the impact of the epidemic on women has grown significantly over time, such that women now account for approximately one in four people living with HIV, according to the CDC.

What is especially important for us to appreciate is the fact that a sizable portion of all people with HIV still do not know their HIV status. The CDC estimates that approximately 18% of all HIV-infected individuals are unaware of their status.

A significant percentage of the children who are infected, moreover, were born to women whose status was unknown. According to the CDC, approximately 27% of the mothers of HIV-infected infants reported from 2003 to 2007 were diagnosed with HIV after delivery, and only 29% of the mothers of infected infants received antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy.

The CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other national organizations have long called for universal prenatal HIV testing to improve the health outcomes of the mother and infant.

On a broader level, the approach to testing has evolved. In 2006, the CDC moved away from targeted risk-based HIV testing recommendations and advised routine opt-out testing for all patients aged 13-64 years. The agency concluded that universal testing is more effective largely because many patients found to be infected did not consider themselves to be at risk. ACOG weighed in the following year, also recommending universal testing with patient notification and an opt-out option, which removes the need for detailed, testing-related informed consent.

Some state laws do not allow opt-out testing and still require affirmative consent, however, so it is important to know your state’s laws. Regardless of your state’s situation, however, failing to test because you deem a patient unlikely to be infected is no longer acceptable.

Testing should be approached just as a blood pressure check is approached – as part of a routine battery of tests that is performed unless the patient declines.

Although the adverse consequences of being identified as HIV positive remain to some extent, it is by no means as severe as it was in the 1980s, when women with positive test results were stigmatized and discriminated against. As primary care providers, we should be reassuring in this regard and much more assertive in making sure patients understand the benefits of testing.

In a related move this year, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is recommending that all patients aged 15-65 years should be screened for HIV, regardless of their risk level.

Treating infection

Strategies for preventing perinatal transmission and managing HIV disease in pregnancy are evolving so rapidly that it is often best for obstetricians who see only a few HIV-infected patients a year to work in consultation with an obstetrician with expertise in HIV in pregnancy, an infectious disease specialist or HIV specialty care provider, or an internist with expert knowledge of the antiretroviral drugs. The National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs in pregnant HIV-infected women, last updated in July 2012, can be a useful reference.

The latest generation of ARV drugs are not only more effective, but also many require only once-a-day dosing schedules, which can improve patient adherence. On the flip side, there are dozens of choices for individualizing treatment, making treatment decisions much more complex than a decade ago.

Among the important trends and changes for ob.gyns to be aware of are the following:

• A "test and treat" paradigm. We are entering a "test and treat" era in the treatment of HIV infection overall, with the paradigm shifting to a much more liberal and immediate recourse to therapy for HIV-infected adults.

Previously, regular monitoring of virologic status would help guide the timing of therapy initiation. For example, CD4 T-lymphocyte counts of less than 350 mm3 or plasma HIV RNA levels that exceeded certain thresholds were the recommended triggers for initiation of ARV therapy. Although there remains some disagreement among experts who support treating a patient when CD4 counts reach 550 mm3 and experts who support treating a patient regardless of CD4 or viral load, I believe the scale is tipping toward treating almost everyone upon diagnosis. Waiting until patients have become more immunocompromised and reached a chronic infection–induced inflammatory state can drive the development of cardiovascular disease and other long-term health care problems.

While some debate persists as to whether all HIV-infected individuals should begin treatment regardless of CD4 count, there is no question as to the appropriate approach for the pregnant woman.

For HIV-infected pregnant women, it is currently recommended that a combination ARV drug regimen be implemented as early as possible antepartum to prevent perinatal transmission, regardless of HIV RNA copy number or CD4 T-lymphocyte count. Evidence that transmission may be lowered with earlier initiation of ART, combined with growing evidence regarding the safety of ARV drugs, has shifted the mindset from a paradigm of avoiding therapy in the first trimester unless absolutely necessary, to a slightly more aggressive approach with earlier initiation of ARV drugs.

Women who enter pregnancy on an effective ARV regimen should continue this regimen without disruption, as drugs changes during pregnancy may be associated with loss of viral control and increased risk of perinatal transmission.

• Lessening concern about risks. Certainly, the known benefits of ARV drugs for a pregnant woman must be weighed against the potential risks of adverse events to the woman, fetus, and newborn. The NIH clinical guidelines categorize various antiretroviral agents for use in pregnancy as preferred, alternative, or for "use in special circumstances."

In general, however, we have acquired more information on the safety of many of these drugs in pregnancy. As data have accumulated, concerns about potential teratogenic effects and other adverse effects of ARV drugs on fetuses and newborns have lessened.

For example, long-standing concerns about tenofovir decreasing fetal bone porosity and potentially causing other anomalies have lessened with recent studies suggesting that adverse events from tenofovir occur infrequently. The use of other drugs, such as efavirenz, also has been liberalized with recent evidence showing that the risk of adverse events is much lower than once believed; recent guidelines now advise that efavirenz rarely needs to be discontinued among women who were receiving it prior to pregnancy.

Obstetricians’ chief role in working with consultants is to ensure that a less-effective drug is not prescribed merely because a patient is pregnant. An effective Class C drug should not be replaced by an ineffective Class B drug solely because an internist does not understand drug use in pregnancy. Obstetricians understand that risks of drugs must be balanced against the risks of untreated diseases.