User login

Hand infections, if not treated properly, can cause severe chronic morbidity. The conditions I review here range from superficial to deep seated: herpetic whitlow located in the epidermis; felon in subcutaneous tissue; pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis (FTS) in the tendon sheath; and human bite infection at any level including possibly synovium and bone.

Superficial infections usually respond to nonsurgical management. However, antimicrobial therapy is not straightforward. There is no single regimen that covers all possible pathogens. Combination therapy must usually be started and then tailored once an organism and its susceptibility are known. Subcutaneous, tendon sheath, synovial, and bone infections frequently require surgical management.

Herpetic whitlow

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is common, with as much as 90% of the population exposed by 60 years of age.1 Initial infection usually occurs in the oropharynx and is known as a fever blister or cold sore. However, HSV-1 also can cause herpetic whitlow, a primary infection in the fingertip in which the virus penetrates the subcutaneous tissue, usually after a breakdown in the skin barrier either from infected saliva or the lips of an infected individual.1

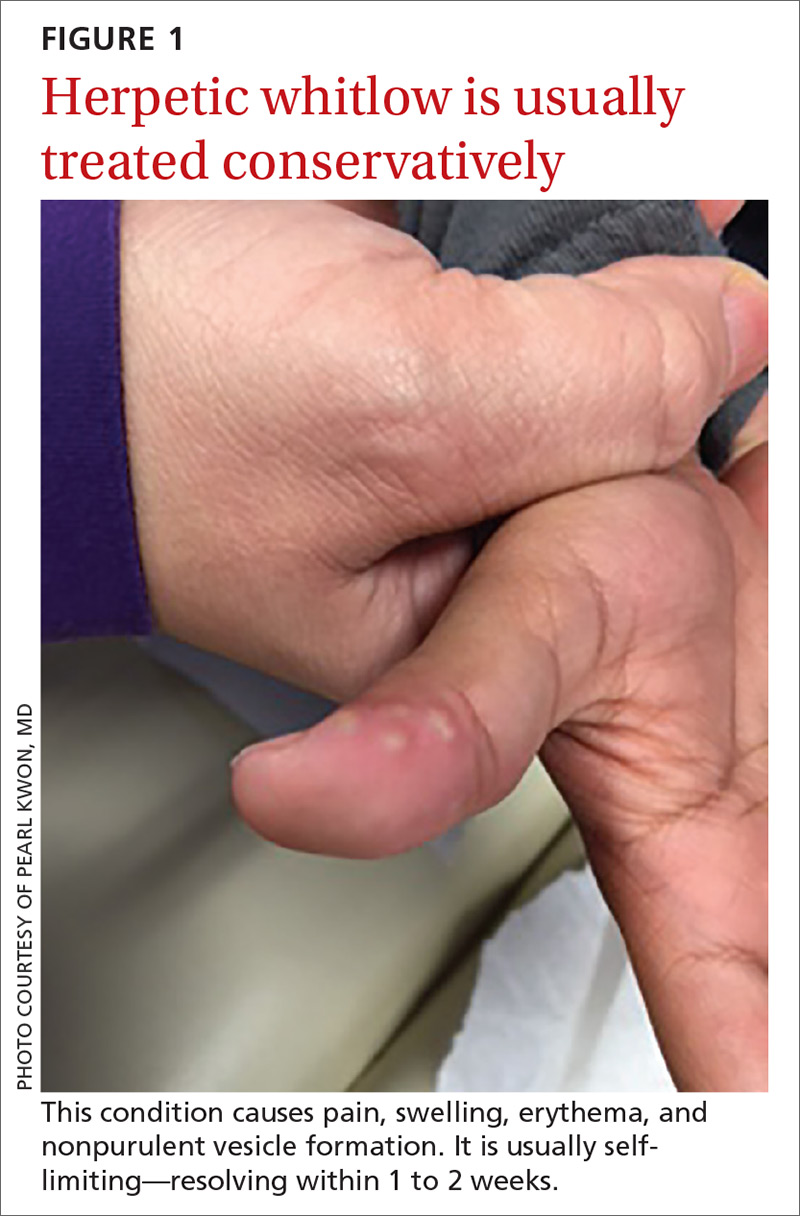

What you’ll see. The lesion is characterized by pain, swelling, erythema, and nonpurulent vesicle formation (FIGURE 1). The condition is usually self-limiting, with the inflammation resolving spontaneously, leaving normal healthy skin within 1 to 2 weeks. Herpetic whitlow is an occupational hazard for medical, nursing, paramedical, and dental personnel, and standard precautions should be used when handling secretions (Strength of Recommendation [SOR]: A).2

Reactivation of HSV-1 (and HSV-2) is common, with a prodrome of a “tingling sensation” and subsequent blister formation in the same location as the previous infection. It can cause pain and discomfort and may render the individual unable to perform usual activities.1,3 This lesion is often confused with bacterial (pyogenic) infections of the pulp of the finger or thumb (felon).1 Herpetic whitlow can be distinguished from a felon by its formation of vesicles, lack of a tense pulp space, and serous, rather than purulent, drainage. Scarring is not associated with herpes infection because penetration is limited to the epidermal area. Superimposed bacterial infection can be mistaken for an abscess (felon) and lead to unnecessary incision and drainage, causing associated morbidity and potential scarring in the affected area.1

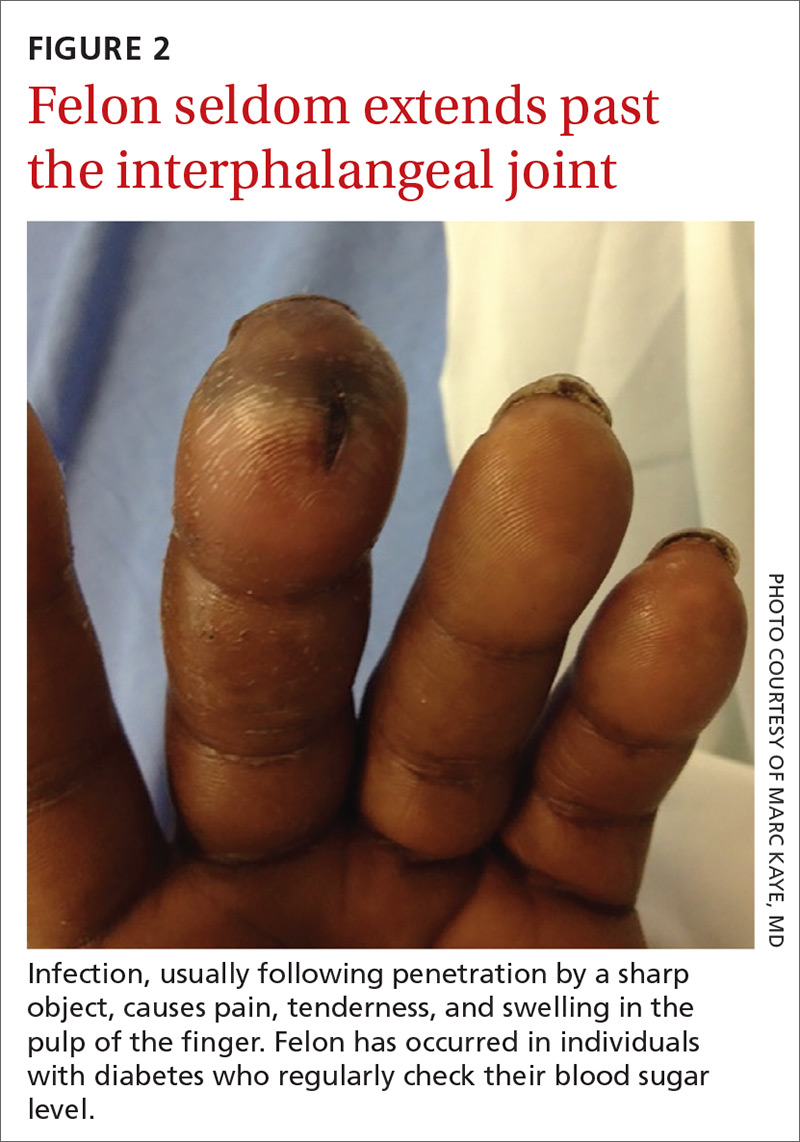

How it’s treated. Treatment of herpetic whitlow is usually conservative, and topical application of acyclovir 5% appears to be beneficial (SOR: C).4 Two studies also suggest that oral acyclovir is beneficial for herpetic whitlow and may reduce the frequency of recurrence.5,6 Controlled studies in the use of acyclovir for herpetic whitlow have not been conducted. Despite a lack of direct evidence, acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir are accepted therapies for herpetic whitlow (TABLE 17) (SOR: B).6,8

Felon

A felon is a closed-space infection affecting the pulp of the fingers or thumb. The anatomy of the finger is unique in that there are multiple septa attaching the periosteum to the skin, thereby creating several closed spaces prone to develop pockets of infection.

Continue to: What you'll see

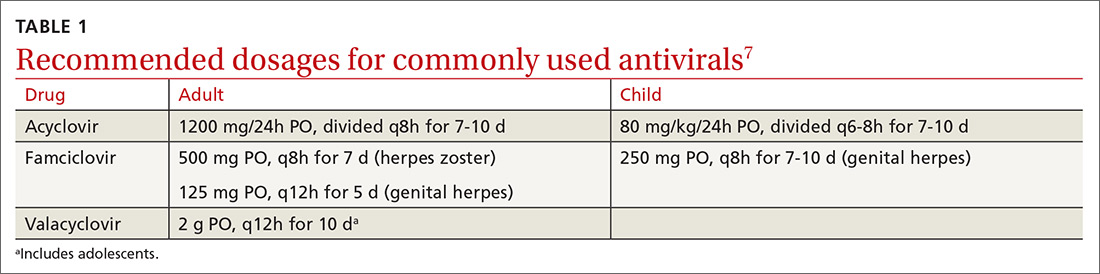

What you’ll see. Clinical signs and symptoms include pain in the pulp of the finger with tenderness and swelling. Bacteria are usually introduced into fingertip space (fat pad) by a penetrating object. Some reported cases have involved individuals with diabetes who regularly check their blood sugar (FIGURE 2).9 A defining characteristic is that the infection usually does not extend past the interphalangeal joint. Radiologic evaluation may be necessary to detect the presence of foreign bodies or to assess bone involvement (osteomyelitis of the distal phalanx).10 The differential diagnosis includes paronychia, in which the infection starts in the nail area and pain is not as intense as in a felon infection.11

How it’s treated. Surgical treatment of felon is controversial. There is no doubt that pus should be drained; how the incision is best performed, however, has been debated.12 Before surgical debridement, obtain a sample of pus for Gram stain and for cultures of aerobic and anaerobic organisms, acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and fungi (SOR: A).13,14 Several surgical techniques and their pitfalls are described in the literature.

Lateral and tip incisions may help avoid painful scars. However, multiple reports of this procedure describe injury to neurovascular bundles, leading to ischemia and anesthesia.12 The “fish-mouth” incision and the “hockey stick” or “J” incision, as well as the transverse palmar incision, are no longer recommended due to painful sequelae, sensorial alterations, and risk of cutting the digital nerves.15 The preferred surgical procedure at this time is to make a very short incision over the area of maximum tenderness, then open and drain the abscess. Avoid placing packing in the affected area. Post-surgical management includes elevation, immobilization with an appropriate splint, and application of compresses until the wound has healed.12,15,16

Since Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus sp are the most common bacteria causing felon, start

Acute pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis

FTS is an aggressive closed-space bacterial infection that involves the flexor tendon synovial sheath. FTS accounts for up to 10% of acute hand infections and requires prompt medical attention with wound lavage, surgical management, and antimicrobial therapy to minimize serious consequences to the digit.18

Continue to: What you'll see

What you’ll see. FTS is diagnosed using clinical criteria19,20: fusiform swelling of the finger; exquisite tenderness over the entire course of the flexor tendon sheath; pain on passive extension; and flexed posture of the digit (FIGURE 3). Patients usually recall some type of trauma or puncture wound to the affected area, but hematogenous spread of Neisseria gonorrhoeae also has been reported.21 The most common bacterial pathogens are Staphylococcus sp or Streptococcus sp. However, obtain a sample for Gram stain and culture for aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, and fungal agents before irrigating the wound with copious fluids and initiating empirical antibiotic therapy.14 Once a pathogen has been isolated, tailor antimicrobial therapy based on identified sensitivities and local antibiogram.13

How it’s treated. Early treatment of FTS is of utmost importance to avoid adverse outcomes. If FTS is diagnosed early, manage conservatively with elevation of the hand, splinting in a neutral position, and intravenous (IV) antibiotics. The use of adjunct antibiotics has improved range-of-motion outcomes compared with elevation and splinting alone (54% excellent vs 14% excellent) (SOR: A).22

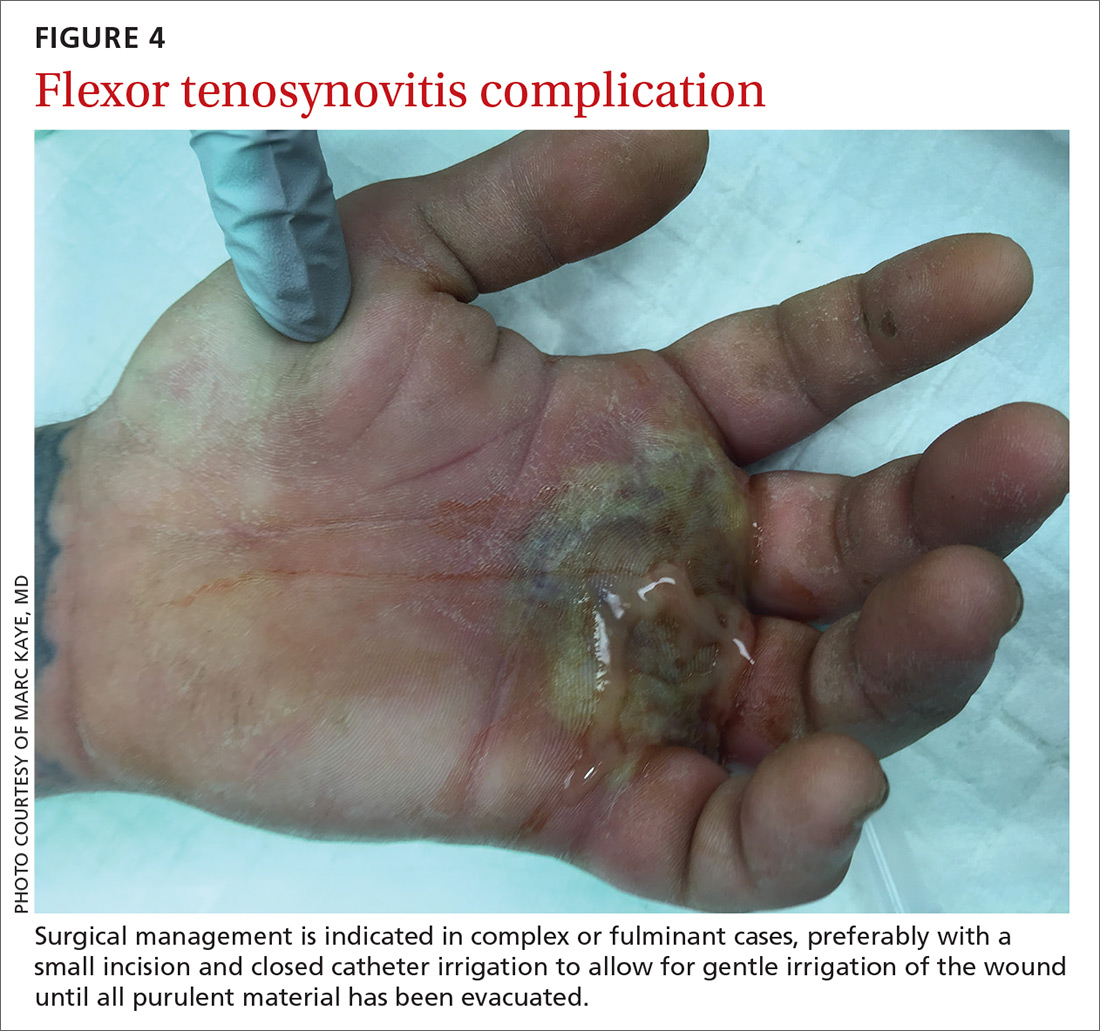

Surgical management of FTS has involved either an open or closed method. The open approach consists of open incision and drainage with exposure of the flexor tendon sheath, followed by large-volume sheath irrigation and closure of incision, in some cases over a drain. The closed approach with irrigation, rather than open washout, has been associated with improved outcomes (71% excellent vs 26% excellent).22 As a result, the procedure of choice is the closed approach, which uses closed catheter irrigation. An incision and placement of an angiocatheter allows for gentle irrigation of the wound until all purulent material has been evacuated (SOR: C).22,23

Human bite injuries

A human bite injury occurs in 1 of 2 ways, and each has a distinct pattern.

What you’ll see

Closed-fist injury occurs when a clenched fist strikes the teeth of another person. The resulting lesion can easily fool a clinician by appearing to show very little damage. If not appropriately evaluated and treated, the lesion can cause considerable morbidity (FIGURE 5). Injury to the extensor mechanism and joint capsule can also damage the articular cartilage and bone, allowing bacteria to grow in a closed environment. This usually affects the metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP) due to its prominence when a hand is clenched. Initially the lesion seems to be minor, with a small laceration of 3 to 5 mm on the overlying skin, thus inoculating mouth flora deep in the hand tissue. Once the hand is relaxed, the broken skin retracts proximally, covering the wound and making it look innocuous.24

Continue to: Occlusive bite injury...

Occlusive bite injury occurs when one individual forcibly bites another. Such wounds tend to be less penetrating than clenched-fist injuries. However, they can vary from superficial lacerations to wounds with tissue loss, including traumatic finger amputation.24,25

One randomized prospective study compared mechanical wound care alone with combined mechanical wound care and oral or IV antibiotics and found that 47% of patients receiving wound care alone became infected vs no infection among those given oral or parenteral antibiotics (SOR: C).26 Experts in the field advise examining the wound after administering a local anesthetic, thereby allowing better visualization of possible tendon damage, joint penetration, fracture, or deep-tissue infection. The procedure should be performed by a physician experienced in treating hand wounds, whether in the emergency department (ED) or in an operating suite.

How it’s treated. There is controversy regarding whether an affected patient can be adequately treated as an outpatient. Most traumatic bite lesions occur in men, and in those abusing drugs or alcohol.25 In the latter case, individuals may be less likely to return for subsequent care or to finish the antibiotic course as prescribed. It is therefore strongly suggested that those individuals be admitted to receive IV antibiotics and physical therapy to expedite healing and avoid morbidity and sequelae of the lesions (SOR: C).25,27

Obtain cultures from the wound after giving analgesia but before starting the procedure. The sample should be sent to the Microbiology Department or outpatient reference lab for aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, and fungal cultures. Recommend that the laboratory use 10% CO2-enriched media for Eikenella corrodens isolation (SOR: A).28,29

Among oral human flora are large concentrations of anaerobic bacteria such as Bacteroides sp (including B fragilis), Prevotella sp, Peptostreptococcus sp, Fusobacterium sp, Veillonella sp, Enterobateriaceae, and Clostridum. B fragilis accounts for up to 41% of isolates in some studies.30 Most of them are beta-lactamase producers. The most common aerobic bacteria are alpha- and beta-hemolytic Streptococci, S aureus, Staphylococcus epidermis, Corynebacterium, and E corrodens. E corrodens accounts for up to 25% of bacteria isolated in clenched-fist injuries.27,29

Continue to: HSV-1 and HSV-2...

HSV-1 and HSV-2, as well as hepatitis B and C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can be isolated in saliva of infected individuals and can be transmitted when contaminated blood is exposed to an open wound. Still, the presence of HIV in saliva is unlikely to result in disease transmission, due to salivary inhibitors rendering the virus non-infective in most cases.25 Obtain HIV and hepatitis B and C serology at baseline and at 3 and 6 months.25 If HIV infection is known or suspected, or if there was exposure to blood in the wound, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends postexposure prophylaxis with a 28-day course of anti-retroviral medication (SOR: A).24,31

Hepatitis B virus has an infectivity 100-fold greater than HIV.27 If possible, the 2 people involved in the altercation should be tested for hepatitis B surface antigen. If the result is positive, the individual with the skin wound should receive hepatitis B immune globulin (0.06 mL/kg/dose),32 and the vaccination schedule started if not done previously (SOR: A).33

Most experts recommend early antibiotic therapy given over 3 to 5 days for fresh, superficial wounds and specifically for wounds affecting hands, feet, joint, and genital area.11 For treatment of cellulitis or abscess, 10 to 14 days is sufficient; tenosynovitis requires 2 to 3 weeks; osteomyelitis requires 4 to 6 weeks.24 Wound care associated with daily dressing changes and antimicrobial therapy was superior to wound care alone (0% vs 47%).30 Assess tetanus status in all cases (SOR: A).17,33,34

Antimicrobial therapy for contamination with oral secretion is not straightforward. No one medication covers all possible pathogens. Use a combination therapy initially and then narrow coverage once the microorganism has been identified and susceptibilities are known. Empirical oral therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanate would be reasonable.

If IV therapy is needed, consider using ampicillin-sulbactam, cefazolin, or clindamycin. These antibiotics usually cover S aureus, Streptococcus sp, E corrodens and some anaerobes. Dicloxacillin will cover S aureus but provides poor coverage for E corrodens. First-generation cephalosporins cover S aureus, but E corrodens resistance is common. For penicillin-allergic individuals, use trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole to cover E corrodens. Doxycycline can be used in children older than 8 years and in adults; avoid it in pregnant women.

Continue to: General principles guiding wound care, microbiology, and antibiotic management

General principles guiding wound care, microbiology, and antibiotic management

Elapsed time between injury and seeking medical attention is characterized as an early (24 hours), late (1-7 days), or delayed (> 7 days) presentation. The timing of an individual’s presentation and a determination of whether the wound is “clean” or “dirty” are both factors in the risk of infection and in associated morbidity and long-term sequelae.

General principles of surgery are important. The cornerstones of treatment are the use of topical anesthesia to provide pain control, which allows for better examination of the wound, debridement of devitalized tissue, collection of wound cultures, and irrigation of the wound with large volume of fluids to mechanically remove dirt, foreign bodies, and bacteria.

Surgical knowledge of hand anatomy increases the likelihood of favorable outcomes in morbidity and functionality. Depending on the circumstances and location, this procedure may be performed by an experienced hand surgeon or an ED physician. (Diversity in settings and available resources may explain why there is so much variability in the composition of patient populations and outcomes found in the medical literature.)

To maximize appropriate bacteriologic success, the Microbiology Department or lab needs to be informed of the type of samples that have been collected. Cultures should be sent for aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, and fungal cultures. Enrichment of aerobic culture with 10% CO2 increases the likelihood of isolating E corrodens (fastidious bacterium), which has been identified in approximately 25% of clenched-fist wounds.

Populations at heightened risk for human bite injuries include alcohol and drug abusers and those of poor socioeconomic status who may not have the resources to visit a medical facility early enough to obtain appropriate medical care. These patients are at risk for being lost to follow-up as well as medication noncompliance, so inpatient admission may diminish the possibilities of incomplete medical treatment, complications, and adverse outcomes such as loss of functionality of the affected extremity.

Continue to: Antimicrobial therapy is not easy

Antimicrobial therapy is not easy. No single regimen covers all possibilities. Start antimicrobial treatment empirically with wide-spectrum coverage, and tailor the regimen, as needed, based on microbiology results.

In clean surgical procedures, S aureus is the most common pathogen. It is acceptable to start empirical treatment with an antistaphylococcal penicillin, first-generation cephalosporin, or clindamycin. In contaminated wounds, gram-negative bacteria, anaerobes, fungal organisms, and mixed infections are more commonly seen.35-37

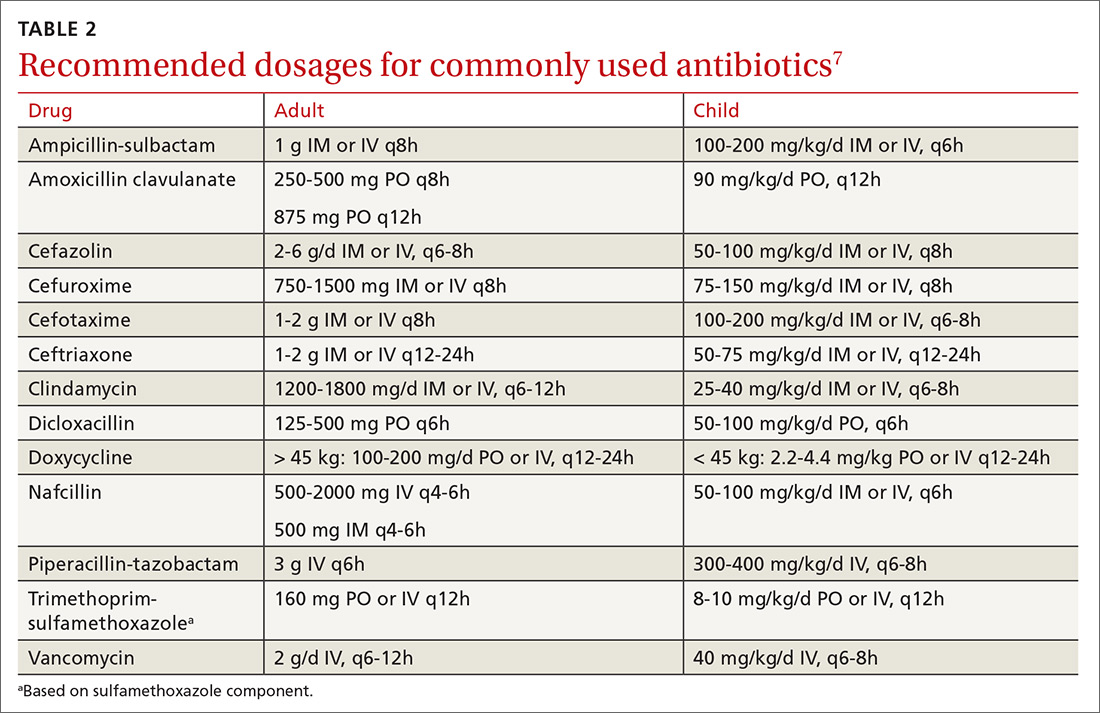

First-generation cephalosporin provides good coverage for gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in clean wounds. However, in contaminated wounds with devitalized tissue, a more aggressive scheme is recommended: start with a penicillin and aminoglycoside.35-37 In some cases, monotherapy with either ampicillin/sulbactam, imipenem, meropenem, piperacillin/tazobactam, or tigecylline may be sufficient until culture results are available; at that point, antibiotic coverage can be narrowed as indicated (TABLE 27).35,36

CORRESPONDENCE

Carlos A. Arango, MD, 8399 Bayberry Road, Jacksonville, FL 32256; carlos.arango@jax.ufl.edu.

1. Lewis MA. Herpes simplex virus: an occupational hazard in dentistry. Int Dent J. 2004;54:103-111.

2. CDC. Recommended infection-control practices for dentistry. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;42:1-16.

3. Merchant VA, Molinari JA, Sabes WR. Herpetic whitlow: report of a case with multiple recurrences. Oral Surg. 1983;555:568-571.

4. Richards DM, Carmine AA, Brogden RN, et al. Acyclovir. A review of its pharmacodynamic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1983;26:378-438.

5. Laskin OL. Acyclovir and suppression of frequently recurring herpetic whitlow. Ann Int Med. 1985;102:494-495.

6. Schwandt NW, Mjos DP, Lubow RM. Acyclovir and the treatment of herpetic whitlow. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64:255-258.

7. Robertson J, Shilkofsk N, eds. The Harriet Lane Handbook. 17th Edition. Maryland Heights, MO; Elsevier Mosby; 2005:679-1009.

8. Usatine PR, Tinitigan R. Nongenital herpes simplex virus. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:1075-1082.

9. Newfield RS, Vargas I, Huma Z. Eikenella corrodens infections. Case report in two adolescent females with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:1011-1013.

10. Patel DB, Emmanuel NB, Stevanovic MV, et al. Hand infections: anatomy, types and spread of infection, imaging findings, and treatment options. Radiographics. 2014; 34:1968-1986.

11. Blumberg G, Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical mimics: an emergency medicine-focused review of cellulitis mimics. J Emerg Med. 2017;53:474-484.

12. Kilgore ES Jr, Brown LG, Newmeyer WL, et al. Treatment of felons. Am J Surgery. 1975;130:194-198.

13. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:e10-e52.

14. Baron EJ, Miller M, Weinstein MP, et al. A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2013 recommendations by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:e22–e121.

15. Clark DC. Common acute hand infections. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:2167-2176.

16. Swope BM. Panonychiae and felons. Op Tech Gen Surgery. 2002;4:270-273.

17. Yen C, Murray E, Zipprich J, et al. Missed opportunities for tetanus postexposure prophylaxis — California, January 2008-March 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:243-246.

18. Barry RL, Adams NS, Martin MD. Pyogenic (suppurative) flexor tenosynovitis: assessment and management. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic7.

19. The symptoms, signs, and diagnosis of tenosynovitis and major facial space abscess. In: Kanavel AB, ed. Infections of the Hand. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1912:201-226.

20. Kennedy CD, Huang JI, Hanel DP. In brief: Kanavel’s signs and pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. Clin Ortho Relat Res. 2016;474;280-284.

21. Krieger LE, Schnall SB, Holtom PD, et al. Acute gonococcal flexor tenosynovitis. Orthopedics. 1997;20:649-650.

22. Giladi AM, Malay S, Chung KC. A systematic review of the management of acute pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2015;40:720-728.

23. Gutowski KA, Ochoa O, Adams WP Jr. Closed-catheter irrigation is as effective as open drainage for treatment of pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. Ann Plastic Surgery. 2002;49:350-354.

24. Kennedy SA, Stoll LE, Lauder AS. Human and other mammalian bite injuries of the hand: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:47-57.

25. Henry FP, Purcell EM, Eadie PA. The human bite injury: a clinical audit and discussion regarding the management of this alcohol fueled phenomenon. Emer Med J. 2007;24:455-458.

26. Zubowicz VN, Gravier M. Management of early human bites of the hand: a prospective randomized study. Plas Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:111-114.

27. Kelly IP, Cunney RJ, Smyth EG, et al. The management of human bite injuries of the hand. Injury. 1996;27:481-484.

28. Udaka T, Hiraki N, Shiomori T, et al. Eikenella corrodens in head and neck infections. J Infect. 2007;54:343-348.

29. Decker MD. Eikenella corrodens. Infect Control. 1986;7:36-41.

30. Griego RD, Rosen T, Orengo IF, et al. Dog, cats, and human bites: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:1019-1029.

31. Panlilio AL, Cardo DM, Grohskopf LA, et al. Updated U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1:17.

32. American Academy of Pediatrics. Hepatitis B. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS. Eds. Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018:415.

33. Chapman LE, Sullivent EE, Grohskopf LA, et al. Recommendations for postexposure interventions to prevent infection with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, or human immunodeficiency virus, and tetanus in persons wounded during bombings and other mass-casualty events—United States, 2008: recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1-21.

34. Harrison M. A 4-year review of human bite injuries presenting to emergency medicine and proposed evidence-based guidelines. Injury. 2009;40:826-830.

35. Taplitz RA. Managing bite wounds. Currently recommended antibiotics for treatment and prophylaxis. Postgrad Med. 2004;116:49-52.

36. Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:705-710.

37. Shapiro DB. Postoperative infection in hand surgery. Cause, prevention, and treatment. Hands Clinic. 1998;14:669-681.

Hand infections, if not treated properly, can cause severe chronic morbidity. The conditions I review here range from superficial to deep seated: herpetic whitlow located in the epidermis; felon in subcutaneous tissue; pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis (FTS) in the tendon sheath; and human bite infection at any level including possibly synovium and bone.

Superficial infections usually respond to nonsurgical management. However, antimicrobial therapy is not straightforward. There is no single regimen that covers all possible pathogens. Combination therapy must usually be started and then tailored once an organism and its susceptibility are known. Subcutaneous, tendon sheath, synovial, and bone infections frequently require surgical management.

Herpetic whitlow

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is common, with as much as 90% of the population exposed by 60 years of age.1 Initial infection usually occurs in the oropharynx and is known as a fever blister or cold sore. However, HSV-1 also can cause herpetic whitlow, a primary infection in the fingertip in which the virus penetrates the subcutaneous tissue, usually after a breakdown in the skin barrier either from infected saliva or the lips of an infected individual.1

What you’ll see. The lesion is characterized by pain, swelling, erythema, and nonpurulent vesicle formation (FIGURE 1). The condition is usually self-limiting, with the inflammation resolving spontaneously, leaving normal healthy skin within 1 to 2 weeks. Herpetic whitlow is an occupational hazard for medical, nursing, paramedical, and dental personnel, and standard precautions should be used when handling secretions (Strength of Recommendation [SOR]: A).2

Reactivation of HSV-1 (and HSV-2) is common, with a prodrome of a “tingling sensation” and subsequent blister formation in the same location as the previous infection. It can cause pain and discomfort and may render the individual unable to perform usual activities.1,3 This lesion is often confused with bacterial (pyogenic) infections of the pulp of the finger or thumb (felon).1 Herpetic whitlow can be distinguished from a felon by its formation of vesicles, lack of a tense pulp space, and serous, rather than purulent, drainage. Scarring is not associated with herpes infection because penetration is limited to the epidermal area. Superimposed bacterial infection can be mistaken for an abscess (felon) and lead to unnecessary incision and drainage, causing associated morbidity and potential scarring in the affected area.1

How it’s treated. Treatment of herpetic whitlow is usually conservative, and topical application of acyclovir 5% appears to be beneficial (SOR: C).4 Two studies also suggest that oral acyclovir is beneficial for herpetic whitlow and may reduce the frequency of recurrence.5,6 Controlled studies in the use of acyclovir for herpetic whitlow have not been conducted. Despite a lack of direct evidence, acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir are accepted therapies for herpetic whitlow (TABLE 17) (SOR: B).6,8

Felon

A felon is a closed-space infection affecting the pulp of the fingers or thumb. The anatomy of the finger is unique in that there are multiple septa attaching the periosteum to the skin, thereby creating several closed spaces prone to develop pockets of infection.

Continue to: What you'll see

What you’ll see. Clinical signs and symptoms include pain in the pulp of the finger with tenderness and swelling. Bacteria are usually introduced into fingertip space (fat pad) by a penetrating object. Some reported cases have involved individuals with diabetes who regularly check their blood sugar (FIGURE 2).9 A defining characteristic is that the infection usually does not extend past the interphalangeal joint. Radiologic evaluation may be necessary to detect the presence of foreign bodies or to assess bone involvement (osteomyelitis of the distal phalanx).10 The differential diagnosis includes paronychia, in which the infection starts in the nail area and pain is not as intense as in a felon infection.11

How it’s treated. Surgical treatment of felon is controversial. There is no doubt that pus should be drained; how the incision is best performed, however, has been debated.12 Before surgical debridement, obtain a sample of pus for Gram stain and for cultures of aerobic and anaerobic organisms, acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and fungi (SOR: A).13,14 Several surgical techniques and their pitfalls are described in the literature.

Lateral and tip incisions may help avoid painful scars. However, multiple reports of this procedure describe injury to neurovascular bundles, leading to ischemia and anesthesia.12 The “fish-mouth” incision and the “hockey stick” or “J” incision, as well as the transverse palmar incision, are no longer recommended due to painful sequelae, sensorial alterations, and risk of cutting the digital nerves.15 The preferred surgical procedure at this time is to make a very short incision over the area of maximum tenderness, then open and drain the abscess. Avoid placing packing in the affected area. Post-surgical management includes elevation, immobilization with an appropriate splint, and application of compresses until the wound has healed.12,15,16

Since Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus sp are the most common bacteria causing felon, start

Acute pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis

FTS is an aggressive closed-space bacterial infection that involves the flexor tendon synovial sheath. FTS accounts for up to 10% of acute hand infections and requires prompt medical attention with wound lavage, surgical management, and antimicrobial therapy to minimize serious consequences to the digit.18

Continue to: What you'll see

What you’ll see. FTS is diagnosed using clinical criteria19,20: fusiform swelling of the finger; exquisite tenderness over the entire course of the flexor tendon sheath; pain on passive extension; and flexed posture of the digit (FIGURE 3). Patients usually recall some type of trauma or puncture wound to the affected area, but hematogenous spread of Neisseria gonorrhoeae also has been reported.21 The most common bacterial pathogens are Staphylococcus sp or Streptococcus sp. However, obtain a sample for Gram stain and culture for aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, and fungal agents before irrigating the wound with copious fluids and initiating empirical antibiotic therapy.14 Once a pathogen has been isolated, tailor antimicrobial therapy based on identified sensitivities and local antibiogram.13

How it’s treated. Early treatment of FTS is of utmost importance to avoid adverse outcomes. If FTS is diagnosed early, manage conservatively with elevation of the hand, splinting in a neutral position, and intravenous (IV) antibiotics. The use of adjunct antibiotics has improved range-of-motion outcomes compared with elevation and splinting alone (54% excellent vs 14% excellent) (SOR: A).22

Surgical management of FTS has involved either an open or closed method. The open approach consists of open incision and drainage with exposure of the flexor tendon sheath, followed by large-volume sheath irrigation and closure of incision, in some cases over a drain. The closed approach with irrigation, rather than open washout, has been associated with improved outcomes (71% excellent vs 26% excellent).22 As a result, the procedure of choice is the closed approach, which uses closed catheter irrigation. An incision and placement of an angiocatheter allows for gentle irrigation of the wound until all purulent material has been evacuated (SOR: C).22,23

Human bite injuries

A human bite injury occurs in 1 of 2 ways, and each has a distinct pattern.

What you’ll see

Closed-fist injury occurs when a clenched fist strikes the teeth of another person. The resulting lesion can easily fool a clinician by appearing to show very little damage. If not appropriately evaluated and treated, the lesion can cause considerable morbidity (FIGURE 5). Injury to the extensor mechanism and joint capsule can also damage the articular cartilage and bone, allowing bacteria to grow in a closed environment. This usually affects the metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP) due to its prominence when a hand is clenched. Initially the lesion seems to be minor, with a small laceration of 3 to 5 mm on the overlying skin, thus inoculating mouth flora deep in the hand tissue. Once the hand is relaxed, the broken skin retracts proximally, covering the wound and making it look innocuous.24

Continue to: Occlusive bite injury...

Occlusive bite injury occurs when one individual forcibly bites another. Such wounds tend to be less penetrating than clenched-fist injuries. However, they can vary from superficial lacerations to wounds with tissue loss, including traumatic finger amputation.24,25

One randomized prospective study compared mechanical wound care alone with combined mechanical wound care and oral or IV antibiotics and found that 47% of patients receiving wound care alone became infected vs no infection among those given oral or parenteral antibiotics (SOR: C).26 Experts in the field advise examining the wound after administering a local anesthetic, thereby allowing better visualization of possible tendon damage, joint penetration, fracture, or deep-tissue infection. The procedure should be performed by a physician experienced in treating hand wounds, whether in the emergency department (ED) or in an operating suite.

How it’s treated. There is controversy regarding whether an affected patient can be adequately treated as an outpatient. Most traumatic bite lesions occur in men, and in those abusing drugs or alcohol.25 In the latter case, individuals may be less likely to return for subsequent care or to finish the antibiotic course as prescribed. It is therefore strongly suggested that those individuals be admitted to receive IV antibiotics and physical therapy to expedite healing and avoid morbidity and sequelae of the lesions (SOR: C).25,27

Obtain cultures from the wound after giving analgesia but before starting the procedure. The sample should be sent to the Microbiology Department or outpatient reference lab for aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, and fungal cultures. Recommend that the laboratory use 10% CO2-enriched media for Eikenella corrodens isolation (SOR: A).28,29

Among oral human flora are large concentrations of anaerobic bacteria such as Bacteroides sp (including B fragilis), Prevotella sp, Peptostreptococcus sp, Fusobacterium sp, Veillonella sp, Enterobateriaceae, and Clostridum. B fragilis accounts for up to 41% of isolates in some studies.30 Most of them are beta-lactamase producers. The most common aerobic bacteria are alpha- and beta-hemolytic Streptococci, S aureus, Staphylococcus epidermis, Corynebacterium, and E corrodens. E corrodens accounts for up to 25% of bacteria isolated in clenched-fist injuries.27,29

Continue to: HSV-1 and HSV-2...

HSV-1 and HSV-2, as well as hepatitis B and C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can be isolated in saliva of infected individuals and can be transmitted when contaminated blood is exposed to an open wound. Still, the presence of HIV in saliva is unlikely to result in disease transmission, due to salivary inhibitors rendering the virus non-infective in most cases.25 Obtain HIV and hepatitis B and C serology at baseline and at 3 and 6 months.25 If HIV infection is known or suspected, or if there was exposure to blood in the wound, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends postexposure prophylaxis with a 28-day course of anti-retroviral medication (SOR: A).24,31

Hepatitis B virus has an infectivity 100-fold greater than HIV.27 If possible, the 2 people involved in the altercation should be tested for hepatitis B surface antigen. If the result is positive, the individual with the skin wound should receive hepatitis B immune globulin (0.06 mL/kg/dose),32 and the vaccination schedule started if not done previously (SOR: A).33

Most experts recommend early antibiotic therapy given over 3 to 5 days for fresh, superficial wounds and specifically for wounds affecting hands, feet, joint, and genital area.11 For treatment of cellulitis or abscess, 10 to 14 days is sufficient; tenosynovitis requires 2 to 3 weeks; osteomyelitis requires 4 to 6 weeks.24 Wound care associated with daily dressing changes and antimicrobial therapy was superior to wound care alone (0% vs 47%).30 Assess tetanus status in all cases (SOR: A).17,33,34

Antimicrobial therapy for contamination with oral secretion is not straightforward. No one medication covers all possible pathogens. Use a combination therapy initially and then narrow coverage once the microorganism has been identified and susceptibilities are known. Empirical oral therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanate would be reasonable.

If IV therapy is needed, consider using ampicillin-sulbactam, cefazolin, or clindamycin. These antibiotics usually cover S aureus, Streptococcus sp, E corrodens and some anaerobes. Dicloxacillin will cover S aureus but provides poor coverage for E corrodens. First-generation cephalosporins cover S aureus, but E corrodens resistance is common. For penicillin-allergic individuals, use trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole to cover E corrodens. Doxycycline can be used in children older than 8 years and in adults; avoid it in pregnant women.

Continue to: General principles guiding wound care, microbiology, and antibiotic management

General principles guiding wound care, microbiology, and antibiotic management

Elapsed time between injury and seeking medical attention is characterized as an early (24 hours), late (1-7 days), or delayed (> 7 days) presentation. The timing of an individual’s presentation and a determination of whether the wound is “clean” or “dirty” are both factors in the risk of infection and in associated morbidity and long-term sequelae.

General principles of surgery are important. The cornerstones of treatment are the use of topical anesthesia to provide pain control, which allows for better examination of the wound, debridement of devitalized tissue, collection of wound cultures, and irrigation of the wound with large volume of fluids to mechanically remove dirt, foreign bodies, and bacteria.

Surgical knowledge of hand anatomy increases the likelihood of favorable outcomes in morbidity and functionality. Depending on the circumstances and location, this procedure may be performed by an experienced hand surgeon or an ED physician. (Diversity in settings and available resources may explain why there is so much variability in the composition of patient populations and outcomes found in the medical literature.)

To maximize appropriate bacteriologic success, the Microbiology Department or lab needs to be informed of the type of samples that have been collected. Cultures should be sent for aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, and fungal cultures. Enrichment of aerobic culture with 10% CO2 increases the likelihood of isolating E corrodens (fastidious bacterium), which has been identified in approximately 25% of clenched-fist wounds.

Populations at heightened risk for human bite injuries include alcohol and drug abusers and those of poor socioeconomic status who may not have the resources to visit a medical facility early enough to obtain appropriate medical care. These patients are at risk for being lost to follow-up as well as medication noncompliance, so inpatient admission may diminish the possibilities of incomplete medical treatment, complications, and adverse outcomes such as loss of functionality of the affected extremity.

Continue to: Antimicrobial therapy is not easy

Antimicrobial therapy is not easy. No single regimen covers all possibilities. Start antimicrobial treatment empirically with wide-spectrum coverage, and tailor the regimen, as needed, based on microbiology results.

In clean surgical procedures, S aureus is the most common pathogen. It is acceptable to start empirical treatment with an antistaphylococcal penicillin, first-generation cephalosporin, or clindamycin. In contaminated wounds, gram-negative bacteria, anaerobes, fungal organisms, and mixed infections are more commonly seen.35-37

First-generation cephalosporin provides good coverage for gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in clean wounds. However, in contaminated wounds with devitalized tissue, a more aggressive scheme is recommended: start with a penicillin and aminoglycoside.35-37 In some cases, monotherapy with either ampicillin/sulbactam, imipenem, meropenem, piperacillin/tazobactam, or tigecylline may be sufficient until culture results are available; at that point, antibiotic coverage can be narrowed as indicated (TABLE 27).35,36

CORRESPONDENCE

Carlos A. Arango, MD, 8399 Bayberry Road, Jacksonville, FL 32256; carlos.arango@jax.ufl.edu.

Hand infections, if not treated properly, can cause severe chronic morbidity. The conditions I review here range from superficial to deep seated: herpetic whitlow located in the epidermis; felon in subcutaneous tissue; pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis (FTS) in the tendon sheath; and human bite infection at any level including possibly synovium and bone.

Superficial infections usually respond to nonsurgical management. However, antimicrobial therapy is not straightforward. There is no single regimen that covers all possible pathogens. Combination therapy must usually be started and then tailored once an organism and its susceptibility are known. Subcutaneous, tendon sheath, synovial, and bone infections frequently require surgical management.

Herpetic whitlow

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is common, with as much as 90% of the population exposed by 60 years of age.1 Initial infection usually occurs in the oropharynx and is known as a fever blister or cold sore. However, HSV-1 also can cause herpetic whitlow, a primary infection in the fingertip in which the virus penetrates the subcutaneous tissue, usually after a breakdown in the skin barrier either from infected saliva or the lips of an infected individual.1

What you’ll see. The lesion is characterized by pain, swelling, erythema, and nonpurulent vesicle formation (FIGURE 1). The condition is usually self-limiting, with the inflammation resolving spontaneously, leaving normal healthy skin within 1 to 2 weeks. Herpetic whitlow is an occupational hazard for medical, nursing, paramedical, and dental personnel, and standard precautions should be used when handling secretions (Strength of Recommendation [SOR]: A).2

Reactivation of HSV-1 (and HSV-2) is common, with a prodrome of a “tingling sensation” and subsequent blister formation in the same location as the previous infection. It can cause pain and discomfort and may render the individual unable to perform usual activities.1,3 This lesion is often confused with bacterial (pyogenic) infections of the pulp of the finger or thumb (felon).1 Herpetic whitlow can be distinguished from a felon by its formation of vesicles, lack of a tense pulp space, and serous, rather than purulent, drainage. Scarring is not associated with herpes infection because penetration is limited to the epidermal area. Superimposed bacterial infection can be mistaken for an abscess (felon) and lead to unnecessary incision and drainage, causing associated morbidity and potential scarring in the affected area.1

How it’s treated. Treatment of herpetic whitlow is usually conservative, and topical application of acyclovir 5% appears to be beneficial (SOR: C).4 Two studies also suggest that oral acyclovir is beneficial for herpetic whitlow and may reduce the frequency of recurrence.5,6 Controlled studies in the use of acyclovir for herpetic whitlow have not been conducted. Despite a lack of direct evidence, acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir are accepted therapies for herpetic whitlow (TABLE 17) (SOR: B).6,8

Felon

A felon is a closed-space infection affecting the pulp of the fingers or thumb. The anatomy of the finger is unique in that there are multiple septa attaching the periosteum to the skin, thereby creating several closed spaces prone to develop pockets of infection.

Continue to: What you'll see

What you’ll see. Clinical signs and symptoms include pain in the pulp of the finger with tenderness and swelling. Bacteria are usually introduced into fingertip space (fat pad) by a penetrating object. Some reported cases have involved individuals with diabetes who regularly check their blood sugar (FIGURE 2).9 A defining characteristic is that the infection usually does not extend past the interphalangeal joint. Radiologic evaluation may be necessary to detect the presence of foreign bodies or to assess bone involvement (osteomyelitis of the distal phalanx).10 The differential diagnosis includes paronychia, in which the infection starts in the nail area and pain is not as intense as in a felon infection.11

How it’s treated. Surgical treatment of felon is controversial. There is no doubt that pus should be drained; how the incision is best performed, however, has been debated.12 Before surgical debridement, obtain a sample of pus for Gram stain and for cultures of aerobic and anaerobic organisms, acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and fungi (SOR: A).13,14 Several surgical techniques and their pitfalls are described in the literature.

Lateral and tip incisions may help avoid painful scars. However, multiple reports of this procedure describe injury to neurovascular bundles, leading to ischemia and anesthesia.12 The “fish-mouth” incision and the “hockey stick” or “J” incision, as well as the transverse palmar incision, are no longer recommended due to painful sequelae, sensorial alterations, and risk of cutting the digital nerves.15 The preferred surgical procedure at this time is to make a very short incision over the area of maximum tenderness, then open and drain the abscess. Avoid placing packing in the affected area. Post-surgical management includes elevation, immobilization with an appropriate splint, and application of compresses until the wound has healed.12,15,16

Since Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus sp are the most common bacteria causing felon, start

Acute pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis

FTS is an aggressive closed-space bacterial infection that involves the flexor tendon synovial sheath. FTS accounts for up to 10% of acute hand infections and requires prompt medical attention with wound lavage, surgical management, and antimicrobial therapy to minimize serious consequences to the digit.18

Continue to: What you'll see

What you’ll see. FTS is diagnosed using clinical criteria19,20: fusiform swelling of the finger; exquisite tenderness over the entire course of the flexor tendon sheath; pain on passive extension; and flexed posture of the digit (FIGURE 3). Patients usually recall some type of trauma or puncture wound to the affected area, but hematogenous spread of Neisseria gonorrhoeae also has been reported.21 The most common bacterial pathogens are Staphylococcus sp or Streptococcus sp. However, obtain a sample for Gram stain and culture for aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, and fungal agents before irrigating the wound with copious fluids and initiating empirical antibiotic therapy.14 Once a pathogen has been isolated, tailor antimicrobial therapy based on identified sensitivities and local antibiogram.13

How it’s treated. Early treatment of FTS is of utmost importance to avoid adverse outcomes. If FTS is diagnosed early, manage conservatively with elevation of the hand, splinting in a neutral position, and intravenous (IV) antibiotics. The use of adjunct antibiotics has improved range-of-motion outcomes compared with elevation and splinting alone (54% excellent vs 14% excellent) (SOR: A).22

Surgical management of FTS has involved either an open or closed method. The open approach consists of open incision and drainage with exposure of the flexor tendon sheath, followed by large-volume sheath irrigation and closure of incision, in some cases over a drain. The closed approach with irrigation, rather than open washout, has been associated with improved outcomes (71% excellent vs 26% excellent).22 As a result, the procedure of choice is the closed approach, which uses closed catheter irrigation. An incision and placement of an angiocatheter allows for gentle irrigation of the wound until all purulent material has been evacuated (SOR: C).22,23

Human bite injuries

A human bite injury occurs in 1 of 2 ways, and each has a distinct pattern.

What you’ll see

Closed-fist injury occurs when a clenched fist strikes the teeth of another person. The resulting lesion can easily fool a clinician by appearing to show very little damage. If not appropriately evaluated and treated, the lesion can cause considerable morbidity (FIGURE 5). Injury to the extensor mechanism and joint capsule can also damage the articular cartilage and bone, allowing bacteria to grow in a closed environment. This usually affects the metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP) due to its prominence when a hand is clenched. Initially the lesion seems to be minor, with a small laceration of 3 to 5 mm on the overlying skin, thus inoculating mouth flora deep in the hand tissue. Once the hand is relaxed, the broken skin retracts proximally, covering the wound and making it look innocuous.24

Continue to: Occlusive bite injury...

Occlusive bite injury occurs when one individual forcibly bites another. Such wounds tend to be less penetrating than clenched-fist injuries. However, they can vary from superficial lacerations to wounds with tissue loss, including traumatic finger amputation.24,25

One randomized prospective study compared mechanical wound care alone with combined mechanical wound care and oral or IV antibiotics and found that 47% of patients receiving wound care alone became infected vs no infection among those given oral or parenteral antibiotics (SOR: C).26 Experts in the field advise examining the wound after administering a local anesthetic, thereby allowing better visualization of possible tendon damage, joint penetration, fracture, or deep-tissue infection. The procedure should be performed by a physician experienced in treating hand wounds, whether in the emergency department (ED) or in an operating suite.

How it’s treated. There is controversy regarding whether an affected patient can be adequately treated as an outpatient. Most traumatic bite lesions occur in men, and in those abusing drugs or alcohol.25 In the latter case, individuals may be less likely to return for subsequent care or to finish the antibiotic course as prescribed. It is therefore strongly suggested that those individuals be admitted to receive IV antibiotics and physical therapy to expedite healing and avoid morbidity and sequelae of the lesions (SOR: C).25,27

Obtain cultures from the wound after giving analgesia but before starting the procedure. The sample should be sent to the Microbiology Department or outpatient reference lab for aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, and fungal cultures. Recommend that the laboratory use 10% CO2-enriched media for Eikenella corrodens isolation (SOR: A).28,29

Among oral human flora are large concentrations of anaerobic bacteria such as Bacteroides sp (including B fragilis), Prevotella sp, Peptostreptococcus sp, Fusobacterium sp, Veillonella sp, Enterobateriaceae, and Clostridum. B fragilis accounts for up to 41% of isolates in some studies.30 Most of them are beta-lactamase producers. The most common aerobic bacteria are alpha- and beta-hemolytic Streptococci, S aureus, Staphylococcus epidermis, Corynebacterium, and E corrodens. E corrodens accounts for up to 25% of bacteria isolated in clenched-fist injuries.27,29

Continue to: HSV-1 and HSV-2...

HSV-1 and HSV-2, as well as hepatitis B and C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can be isolated in saliva of infected individuals and can be transmitted when contaminated blood is exposed to an open wound. Still, the presence of HIV in saliva is unlikely to result in disease transmission, due to salivary inhibitors rendering the virus non-infective in most cases.25 Obtain HIV and hepatitis B and C serology at baseline and at 3 and 6 months.25 If HIV infection is known or suspected, or if there was exposure to blood in the wound, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends postexposure prophylaxis with a 28-day course of anti-retroviral medication (SOR: A).24,31

Hepatitis B virus has an infectivity 100-fold greater than HIV.27 If possible, the 2 people involved in the altercation should be tested for hepatitis B surface antigen. If the result is positive, the individual with the skin wound should receive hepatitis B immune globulin (0.06 mL/kg/dose),32 and the vaccination schedule started if not done previously (SOR: A).33

Most experts recommend early antibiotic therapy given over 3 to 5 days for fresh, superficial wounds and specifically for wounds affecting hands, feet, joint, and genital area.11 For treatment of cellulitis or abscess, 10 to 14 days is sufficient; tenosynovitis requires 2 to 3 weeks; osteomyelitis requires 4 to 6 weeks.24 Wound care associated with daily dressing changes and antimicrobial therapy was superior to wound care alone (0% vs 47%).30 Assess tetanus status in all cases (SOR: A).17,33,34

Antimicrobial therapy for contamination with oral secretion is not straightforward. No one medication covers all possible pathogens. Use a combination therapy initially and then narrow coverage once the microorganism has been identified and susceptibilities are known. Empirical oral therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanate would be reasonable.

If IV therapy is needed, consider using ampicillin-sulbactam, cefazolin, or clindamycin. These antibiotics usually cover S aureus, Streptococcus sp, E corrodens and some anaerobes. Dicloxacillin will cover S aureus but provides poor coverage for E corrodens. First-generation cephalosporins cover S aureus, but E corrodens resistance is common. For penicillin-allergic individuals, use trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole to cover E corrodens. Doxycycline can be used in children older than 8 years and in adults; avoid it in pregnant women.

Continue to: General principles guiding wound care, microbiology, and antibiotic management

General principles guiding wound care, microbiology, and antibiotic management

Elapsed time between injury and seeking medical attention is characterized as an early (24 hours), late (1-7 days), or delayed (> 7 days) presentation. The timing of an individual’s presentation and a determination of whether the wound is “clean” or “dirty” are both factors in the risk of infection and in associated morbidity and long-term sequelae.

General principles of surgery are important. The cornerstones of treatment are the use of topical anesthesia to provide pain control, which allows for better examination of the wound, debridement of devitalized tissue, collection of wound cultures, and irrigation of the wound with large volume of fluids to mechanically remove dirt, foreign bodies, and bacteria.

Surgical knowledge of hand anatomy increases the likelihood of favorable outcomes in morbidity and functionality. Depending on the circumstances and location, this procedure may be performed by an experienced hand surgeon or an ED physician. (Diversity in settings and available resources may explain why there is so much variability in the composition of patient populations and outcomes found in the medical literature.)

To maximize appropriate bacteriologic success, the Microbiology Department or lab needs to be informed of the type of samples that have been collected. Cultures should be sent for aerobic, anaerobic, AFB, and fungal cultures. Enrichment of aerobic culture with 10% CO2 increases the likelihood of isolating E corrodens (fastidious bacterium), which has been identified in approximately 25% of clenched-fist wounds.

Populations at heightened risk for human bite injuries include alcohol and drug abusers and those of poor socioeconomic status who may not have the resources to visit a medical facility early enough to obtain appropriate medical care. These patients are at risk for being lost to follow-up as well as medication noncompliance, so inpatient admission may diminish the possibilities of incomplete medical treatment, complications, and adverse outcomes such as loss of functionality of the affected extremity.

Continue to: Antimicrobial therapy is not easy

Antimicrobial therapy is not easy. No single regimen covers all possibilities. Start antimicrobial treatment empirically with wide-spectrum coverage, and tailor the regimen, as needed, based on microbiology results.

In clean surgical procedures, S aureus is the most common pathogen. It is acceptable to start empirical treatment with an antistaphylococcal penicillin, first-generation cephalosporin, or clindamycin. In contaminated wounds, gram-negative bacteria, anaerobes, fungal organisms, and mixed infections are more commonly seen.35-37

First-generation cephalosporin provides good coverage for gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in clean wounds. However, in contaminated wounds with devitalized tissue, a more aggressive scheme is recommended: start with a penicillin and aminoglycoside.35-37 In some cases, monotherapy with either ampicillin/sulbactam, imipenem, meropenem, piperacillin/tazobactam, or tigecylline may be sufficient until culture results are available; at that point, antibiotic coverage can be narrowed as indicated (TABLE 27).35,36

CORRESPONDENCE

Carlos A. Arango, MD, 8399 Bayberry Road, Jacksonville, FL 32256; carlos.arango@jax.ufl.edu.

1. Lewis MA. Herpes simplex virus: an occupational hazard in dentistry. Int Dent J. 2004;54:103-111.

2. CDC. Recommended infection-control practices for dentistry. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;42:1-16.

3. Merchant VA, Molinari JA, Sabes WR. Herpetic whitlow: report of a case with multiple recurrences. Oral Surg. 1983;555:568-571.

4. Richards DM, Carmine AA, Brogden RN, et al. Acyclovir. A review of its pharmacodynamic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1983;26:378-438.

5. Laskin OL. Acyclovir and suppression of frequently recurring herpetic whitlow. Ann Int Med. 1985;102:494-495.

6. Schwandt NW, Mjos DP, Lubow RM. Acyclovir and the treatment of herpetic whitlow. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64:255-258.

7. Robertson J, Shilkofsk N, eds. The Harriet Lane Handbook. 17th Edition. Maryland Heights, MO; Elsevier Mosby; 2005:679-1009.

8. Usatine PR, Tinitigan R. Nongenital herpes simplex virus. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:1075-1082.

9. Newfield RS, Vargas I, Huma Z. Eikenella corrodens infections. Case report in two adolescent females with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:1011-1013.

10. Patel DB, Emmanuel NB, Stevanovic MV, et al. Hand infections: anatomy, types and spread of infection, imaging findings, and treatment options. Radiographics. 2014; 34:1968-1986.

11. Blumberg G, Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical mimics: an emergency medicine-focused review of cellulitis mimics. J Emerg Med. 2017;53:474-484.

12. Kilgore ES Jr, Brown LG, Newmeyer WL, et al. Treatment of felons. Am J Surgery. 1975;130:194-198.

13. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:e10-e52.

14. Baron EJ, Miller M, Weinstein MP, et al. A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2013 recommendations by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:e22–e121.

15. Clark DC. Common acute hand infections. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:2167-2176.

16. Swope BM. Panonychiae and felons. Op Tech Gen Surgery. 2002;4:270-273.

17. Yen C, Murray E, Zipprich J, et al. Missed opportunities for tetanus postexposure prophylaxis — California, January 2008-March 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:243-246.

18. Barry RL, Adams NS, Martin MD. Pyogenic (suppurative) flexor tenosynovitis: assessment and management. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic7.

19. The symptoms, signs, and diagnosis of tenosynovitis and major facial space abscess. In: Kanavel AB, ed. Infections of the Hand. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1912:201-226.

20. Kennedy CD, Huang JI, Hanel DP. In brief: Kanavel’s signs and pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. Clin Ortho Relat Res. 2016;474;280-284.

21. Krieger LE, Schnall SB, Holtom PD, et al. Acute gonococcal flexor tenosynovitis. Orthopedics. 1997;20:649-650.

22. Giladi AM, Malay S, Chung KC. A systematic review of the management of acute pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2015;40:720-728.

23. Gutowski KA, Ochoa O, Adams WP Jr. Closed-catheter irrigation is as effective as open drainage for treatment of pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. Ann Plastic Surgery. 2002;49:350-354.

24. Kennedy SA, Stoll LE, Lauder AS. Human and other mammalian bite injuries of the hand: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:47-57.

25. Henry FP, Purcell EM, Eadie PA. The human bite injury: a clinical audit and discussion regarding the management of this alcohol fueled phenomenon. Emer Med J. 2007;24:455-458.

26. Zubowicz VN, Gravier M. Management of early human bites of the hand: a prospective randomized study. Plas Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:111-114.

27. Kelly IP, Cunney RJ, Smyth EG, et al. The management of human bite injuries of the hand. Injury. 1996;27:481-484.

28. Udaka T, Hiraki N, Shiomori T, et al. Eikenella corrodens in head and neck infections. J Infect. 2007;54:343-348.

29. Decker MD. Eikenella corrodens. Infect Control. 1986;7:36-41.

30. Griego RD, Rosen T, Orengo IF, et al. Dog, cats, and human bites: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:1019-1029.

31. Panlilio AL, Cardo DM, Grohskopf LA, et al. Updated U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1:17.

32. American Academy of Pediatrics. Hepatitis B. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS. Eds. Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018:415.

33. Chapman LE, Sullivent EE, Grohskopf LA, et al. Recommendations for postexposure interventions to prevent infection with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, or human immunodeficiency virus, and tetanus in persons wounded during bombings and other mass-casualty events—United States, 2008: recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1-21.

34. Harrison M. A 4-year review of human bite injuries presenting to emergency medicine and proposed evidence-based guidelines. Injury. 2009;40:826-830.

35. Taplitz RA. Managing bite wounds. Currently recommended antibiotics for treatment and prophylaxis. Postgrad Med. 2004;116:49-52.

36. Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:705-710.

37. Shapiro DB. Postoperative infection in hand surgery. Cause, prevention, and treatment. Hands Clinic. 1998;14:669-681.

1. Lewis MA. Herpes simplex virus: an occupational hazard in dentistry. Int Dent J. 2004;54:103-111.

2. CDC. Recommended infection-control practices for dentistry. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;42:1-16.

3. Merchant VA, Molinari JA, Sabes WR. Herpetic whitlow: report of a case with multiple recurrences. Oral Surg. 1983;555:568-571.

4. Richards DM, Carmine AA, Brogden RN, et al. Acyclovir. A review of its pharmacodynamic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1983;26:378-438.

5. Laskin OL. Acyclovir and suppression of frequently recurring herpetic whitlow. Ann Int Med. 1985;102:494-495.

6. Schwandt NW, Mjos DP, Lubow RM. Acyclovir and the treatment of herpetic whitlow. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64:255-258.

7. Robertson J, Shilkofsk N, eds. The Harriet Lane Handbook. 17th Edition. Maryland Heights, MO; Elsevier Mosby; 2005:679-1009.

8. Usatine PR, Tinitigan R. Nongenital herpes simplex virus. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:1075-1082.

9. Newfield RS, Vargas I, Huma Z. Eikenella corrodens infections. Case report in two adolescent females with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:1011-1013.

10. Patel DB, Emmanuel NB, Stevanovic MV, et al. Hand infections: anatomy, types and spread of infection, imaging findings, and treatment options. Radiographics. 2014; 34:1968-1986.

11. Blumberg G, Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical mimics: an emergency medicine-focused review of cellulitis mimics. J Emerg Med. 2017;53:474-484.

12. Kilgore ES Jr, Brown LG, Newmeyer WL, et al. Treatment of felons. Am J Surgery. 1975;130:194-198.

13. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:e10-e52.

14. Baron EJ, Miller M, Weinstein MP, et al. A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2013 recommendations by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:e22–e121.

15. Clark DC. Common acute hand infections. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:2167-2176.

16. Swope BM. Panonychiae and felons. Op Tech Gen Surgery. 2002;4:270-273.

17. Yen C, Murray E, Zipprich J, et al. Missed opportunities for tetanus postexposure prophylaxis — California, January 2008-March 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:243-246.

18. Barry RL, Adams NS, Martin MD. Pyogenic (suppurative) flexor tenosynovitis: assessment and management. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic7.

19. The symptoms, signs, and diagnosis of tenosynovitis and major facial space abscess. In: Kanavel AB, ed. Infections of the Hand. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1912:201-226.

20. Kennedy CD, Huang JI, Hanel DP. In brief: Kanavel’s signs and pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. Clin Ortho Relat Res. 2016;474;280-284.

21. Krieger LE, Schnall SB, Holtom PD, et al. Acute gonococcal flexor tenosynovitis. Orthopedics. 1997;20:649-650.

22. Giladi AM, Malay S, Chung KC. A systematic review of the management of acute pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2015;40:720-728.

23. Gutowski KA, Ochoa O, Adams WP Jr. Closed-catheter irrigation is as effective as open drainage for treatment of pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. Ann Plastic Surgery. 2002;49:350-354.

24. Kennedy SA, Stoll LE, Lauder AS. Human and other mammalian bite injuries of the hand: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:47-57.

25. Henry FP, Purcell EM, Eadie PA. The human bite injury: a clinical audit and discussion regarding the management of this alcohol fueled phenomenon. Emer Med J. 2007;24:455-458.

26. Zubowicz VN, Gravier M. Management of early human bites of the hand: a prospective randomized study. Plas Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:111-114.

27. Kelly IP, Cunney RJ, Smyth EG, et al. The management of human bite injuries of the hand. Injury. 1996;27:481-484.

28. Udaka T, Hiraki N, Shiomori T, et al. Eikenella corrodens in head and neck infections. J Infect. 2007;54:343-348.

29. Decker MD. Eikenella corrodens. Infect Control. 1986;7:36-41.

30. Griego RD, Rosen T, Orengo IF, et al. Dog, cats, and human bites: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:1019-1029.

31. Panlilio AL, Cardo DM, Grohskopf LA, et al. Updated U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1:17.

32. American Academy of Pediatrics. Hepatitis B. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS. Eds. Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018:415.

33. Chapman LE, Sullivent EE, Grohskopf LA, et al. Recommendations for postexposure interventions to prevent infection with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, or human immunodeficiency virus, and tetanus in persons wounded during bombings and other mass-casualty events—United States, 2008: recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1-21.

34. Harrison M. A 4-year review of human bite injuries presenting to emergency medicine and proposed evidence-based guidelines. Injury. 2009;40:826-830.

35. Taplitz RA. Managing bite wounds. Currently recommended antibiotics for treatment and prophylaxis. Postgrad Med. 2004;116:49-52.

36. Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:705-710.

37. Shapiro DB. Postoperative infection in hand surgery. Cause, prevention, and treatment. Hands Clinic. 1998;14:669-681.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Obtain a sample of pus for Gram stain and for cultures of aerobic and anaerobic organisms, acid-fast bacilli, and fungi. A

› Use antibiotics as an adjunct to elevation and splinting in flexor tenosynovitis to improve range-of-motion outcomes. A

› Notify your microbiology lab to enrich cultures with 10% CO2 to isolate Eikenella corrodens. A

› Consider prescribing acyclovir, famciclovir, or valacyclovir for herpetic whitlow. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series