User login

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with impaired psychosocial functioning,1-4 reduced health-related quality of life,5 high utilization of services,6,7 and excess mortality.8-10 Although BPD occurs in up to 40% of psychiatric inpatients11 and 10% of outpatients,12 it is underrecognized.13-15 Often, patients with BPD do not receive an accurate diagnosis until ≥10 years after initially seeking treatment.16 The treatment and clinical implications of failing to recognize BPD include overprescribing medication and underutilizing empirically effective psychotherapies.14

This review summarizes studies of the underdiagnosis of BPD in routine clinical practice, describes which patients should be screened, and reviews alternative approaches to screening.

Underrecognition of BPD

The Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) project is an ongoing clinical research study involving the integration of research assessment methods into routine clinical practice.17 In an early report from the MIDAS project, BPD diagnoses derived from structured and unstructured clinical interviews were compared between 2 groups of psychiatric outpatients in the same practice.15 Individuals in the structured interview cohort were 35 times more often diagnosed with BPD than individuals evaluated with an unstructured clinical interview. Importantly, when the information from the structured interview was presented to the clinicians, BPD was more likely to be diagnosed clinically.

Other studies13,16 also found that the rate of diagnosing BPD was higher when the diagnosis was based on a semi-structured diagnostic interview compared with an unstructured clinical interview, and that clinicians were reluctant to diagnose BPD during their routine intake diagnostic evaluation.

Clinicians, however, do not use semi-structured interviews in their practice, and they also do not tend to diagnose personality disorders (PDs) based on direct questioning, as they typically would when assessing a symptom-based disorder such as depression or anxiety. Rather, clinicians report that they rely on longitudinal observations to diagnose PDs.18 However, the results from the MIDAS project were inconsistent with clinicians’ reports. When clinicians were presented with the results of the semi-structured interview, they usually would diagnose BPD, even though it was the initial evaluation. If clinicians actually relied on longitudinal observations and considered information based on the direct question approach of research interviews to be irrelevant or invalid, then the results from the semi-structured interview should not have influenced the rate at which they diagnosed BPD. This suggests that the primary issue in diagnosing PDs is not the need for longitudinal observation but rather the need for more information, and that there is a role for screening questionnaires.

One potential criticism of studies demonstrating underrecognition of BPD in clinical practice is that patients typically were interviewed when they presented for treatment, when most were depressed or anxious. The possible pathologizing effects of psychiatric state on personality have been known for years.19 However, a large body of literature examining the treatment, prognostic, familial, and biological correlates of PDs supports the validity of diagnosing PDs in this manner. Moreover, from a clinical perspective, the sooner a clinician is aware of the presence of BPD, the more likely this information can be used for treatment planning.

Who should be screened for BPD?

BPD is underrecognized and underdiagnosed because patients with BPD often also have comorbid mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders.20,21 The symptoms associated with these disorders are typically the chief concern of patients with undiagnosed BPD who present for treatment. Patients with BPD rarely present for an intake evaluation and state that they are struggling with abandonment fears, chronic feelings of emptiness, or an identity disturbance. If patients identified these problems as their chief concerns, BPD would be easier to recognize.

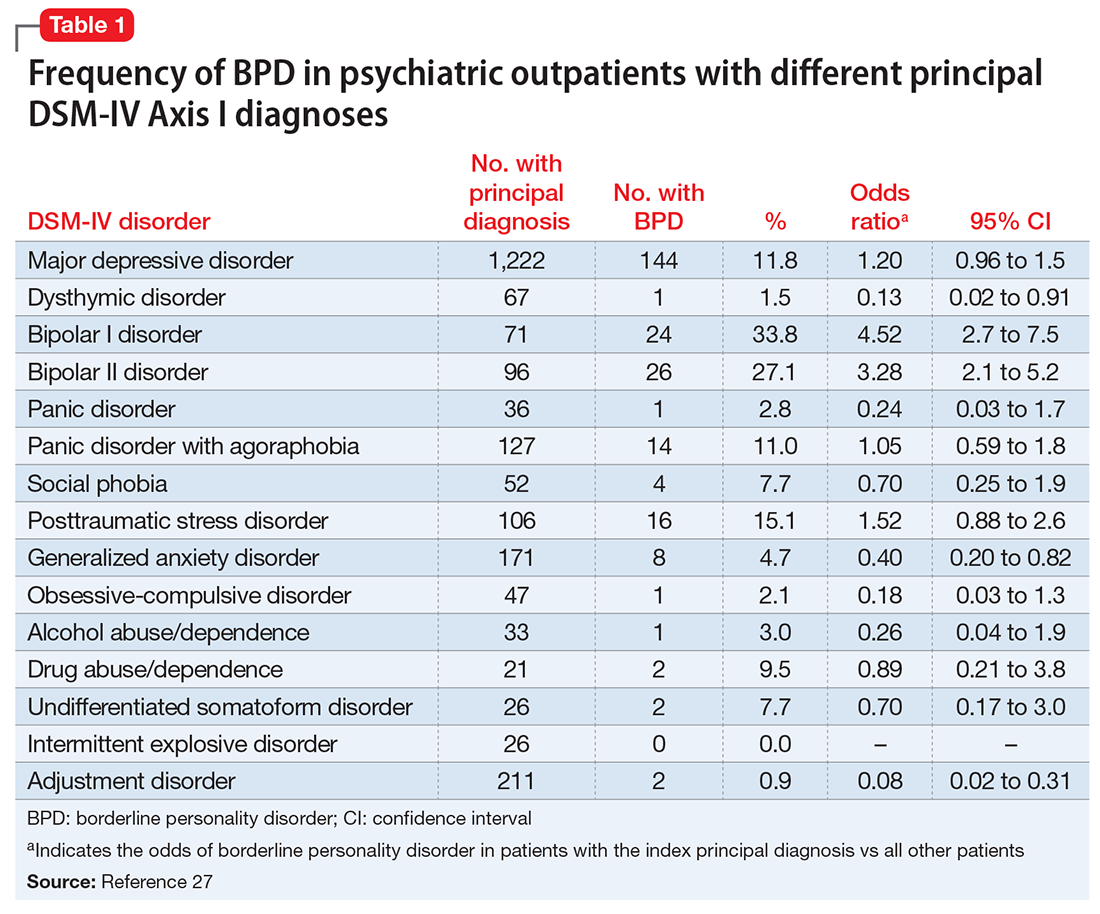

Although several studies have documented the frequency of BPD in patients with a specific psychiatric diagnosis such as major depressive disorder (MDD) or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,22-26 the MIDAS project examined the frequency of BPD in patients with various diagnoses and evaluated which disorders were associated with a significantly increased rate of BPD.27 The highest rate of BPD was found in patients with bipolar disorder. Approximately 25% of patients with bipolar II disorder and one-third of those with bipolar I disorder were diagnosed with BPD; these rates were significantly higher than the rate of BPD in patients without these disorders (Table 127). The rate of BPD was second highest in patients with a principal diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and MDD; however, the rate of BPD in these patients was not significantly elevated compared with patients who did not have these principal diagnoses. Three disorders were associated with a significantly lower rate of BPD: adjustment disorder, dysthymic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder.

It would be easy to recommend screening for BPD in all psychiatric patients. However, that is not feasible or practical. In making screening recommendations, absolute risk should be considered more important than relative risk. Clinicians should screen for BPD in patients presenting to a general psychiatric outpatient practice with a principal diagnosis of MDD, bipolar disorder, PTSD, or panic disorder with agoraphobia. That is, I recommend screening for BPD in patients with a principal diagnosis in which the prevalence of BPD is ≥10% (Table 127).

A brief review of screening statistics

Screening tests for most psychiatric disorders are based on multi-item scales in which a total score is computed from a sum of item scores, and a cutoff point is established to determine who does and does not screen positive on the test. However, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values are not invariant properties of a screening test with a continuous score distribution. Rather, the performance statistics of a scale can be altered by changing the threshold score to distinguish cases from non-cases. When the screening threshold is lowered, sensitivity increases and specificity decreases.

For screening, a broad net needs to be cast so that all (or almost all) cases are included. Therefore, the cutoff score should be set low to prioritize the sensitivity of the instrument. A screening scale also should have high negative predictive value so that the clinician can be confident that patients who screen negative on the test do not have the disorder.

Screening questionnaires for BPD

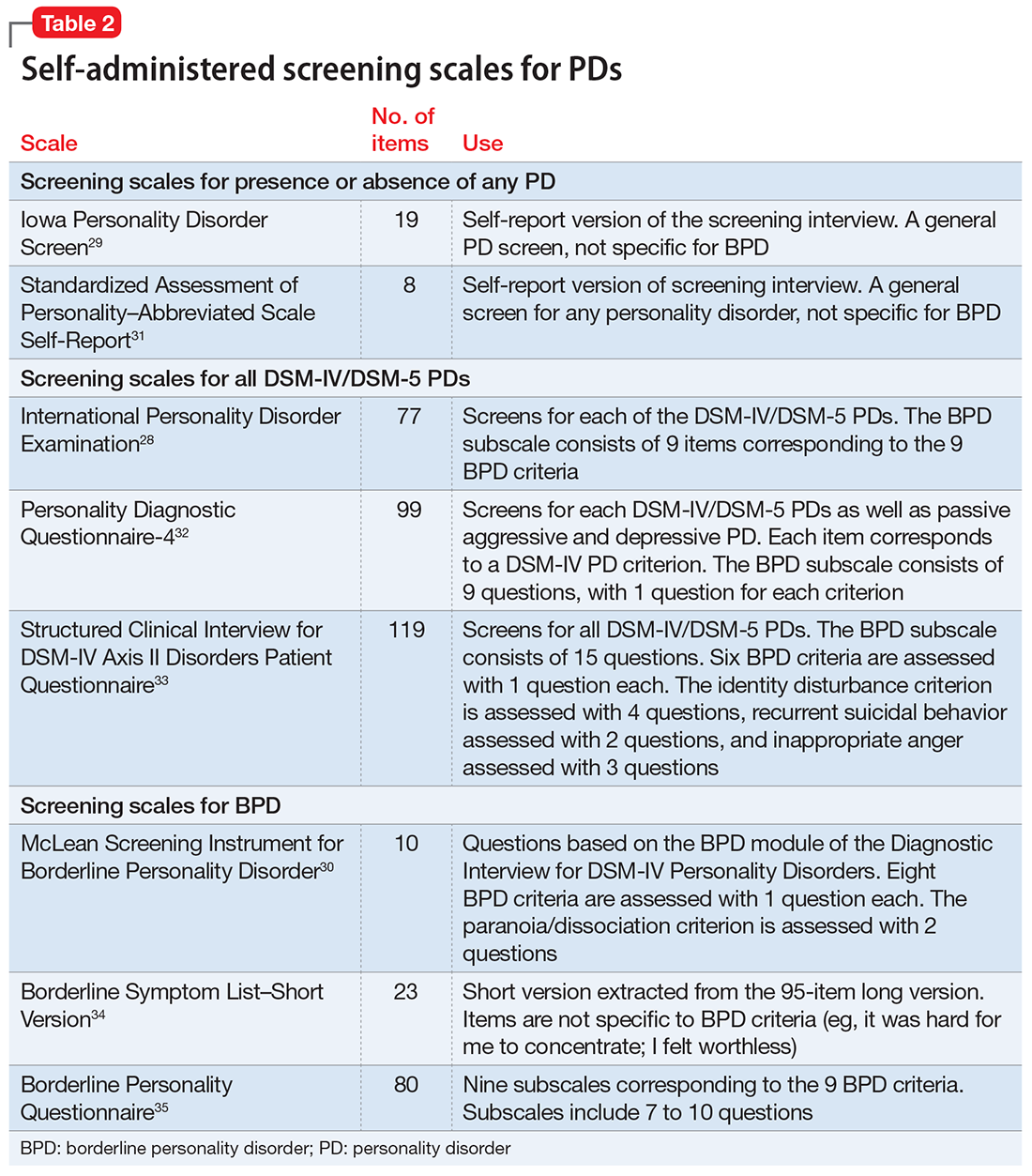

Several questionnaires have been developed to screen for PDs (Table 228-35). Some screen for each of the DSM PDs,28,36-42 and some screen more broadly for the presence or absence of any PD.29,43,44 The most commonly studied self-report scale for BPD is the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD),30 a 10-item self-report scale derived from a subset of questions from the BPD module of a semi-structured diagnostic interview.

The initial validation study30 found that the optimal cutoff score was 7, which resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 89%. Three studies have evaluated the scale in adolescents and young adults,45-47 and 3 studies examined the scale in adult outpatients.48-50 Across all 6 studies, at the optimal cutoff scores determined in each study, the sensitivity of the MSI-BPD ranged from 68% to 94% (mean, 80%) and the specificity ranged from 66% to 80% (mean, 72%).

Problems with screening questionnaires. Although screening scales have been developed for many psychiatric disorders, they have not been widely used in mental health settings. In a previous commentary, I argued that the conceptual justification for using self-report screening scales for single disorders in psychiatric settings is questionable.51 Another problem with screening scales is their potential misuse as case-finding instruments. In the literature on bipolar disorder screening, several researchers misconstrued a positive screen to indicate caseness.51 Although this is not a problem with the screening measures or the selection of a cutoff score, caution must be taken to not confuse screening with diagnosis.52

Screening for BPD as part of your diagnostic interview

An alternative approach to using self-administered questionnaires for screening is for clinicians to include questions in their evaluation as part of a psychiatric review of systems. When conducting a diagnostic interview, clinicians typically screen for disorders that are comorbid with the principal diagnosis by asking about the comorbid disorders’ necessary features or “gate criteria.” For example, in a patient with a principal diagnosis of MDD, the clinician would inquire about the presence of panic attacks, excessive worry, or substance use to screen for the presence of panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or a substance use disorder. In contrast, for polythetically defined disorders such as BPD, there is no single gate criterion, because the disorder is diagnosed based on the presence of at least 5 of 9 criteria and no single one of these criteria is required to be present to establish the diagnosis.

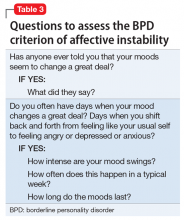

As part of the MIDAS project, the psychometric properties of the BPD criteria were examined to determine if it was possible to identify 1 or 2 criteria that could serve as gate criteria to screen for the disorder. If the sensitivity of 1 criterion or a combination of 2 BPD criteria was sufficiently high (ie, >90%), then the assessment of this criterion (or these criteria) could be included in a psychiatric review of systems, thus potentially improving the detection of BPD. Researchers hypothesized that affective instability, considered first by Linehan53 and later by other theorists54 to be of central importance to the clinical manifestations of BPD, could function as a gate criterion. In the sample of 3,674 psychiatric outpatients who were evaluated with a semi-structured interview, the sensitivity of the affective instability criterion was 92.8%, and the negative predictive value of the criterion was 99%.

Identifying a single BPD criterion that is present in the vast majority of patients diagnosed with BPD will allow clinicians to follow their usual clinical practice when conducting a psychiatric review of systems and inquire about the gate criteria of various disorders. Several studies have found that >90% of patients with BPD report affective instability. However, this does not mean that the diagnosis of BPD can be abbreviated to an assessment of the presence or absence of affective instability. Many patients who screen positive will not have BPD when a more definitive diagnostic evaluation is conducted. In the case of BPD, the more costly definitive diagnostic procedure simply entails inquiry of the other diagnostic criteria.

1. Bellino S, Patria L, Paradiso E, et al. Major depression in patients with borderline personality disorder: a clinical investigation. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(4):234-238.

2. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):276-283.

3. Gunderson JG, Stout RL, McGlashan TH, et al. Ten-year course of borderline personality disorder: psychopathology and function from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):827-837.

4. Zanarini MC, Jacoby RJ, Frankenburg FR, et al. The 10-year course of social security disability income reported by patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(4):346-356.

5. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533-545.

6. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):295-302.

7. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al. Mental health service utilization by borderline personality disorder patients and Axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for 6 years. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(1):28-36.

8. Pompili M, Girardi P, Ruberto A, et al. Suicide in borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Nord J Psychiatry. 2005;59(5):319-324.

9. Oldham JM. Borderline personality disorder and suicidality. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):20-26.

10. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(3):226-239.

11. Marinangeli M, Butti G, Scinto A, et al. Patterns of comorbidity among DSM-III-R personality disorders. Psychopathology. 2000;33(2):69-74.

12. Zimmerman M, Rothschild L, Chelminski I. The frequency of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1911-1918.

13. Comtois KA, Carmel A. Borderline personality disorder and high utilization of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization: concordance between research and clinical diagnosis. J Behav Health Servi Res. 2016;43(2):272-280.

14. Paris J, Black DW. Borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder: what is the difference and why does it matter? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(1):3-7.

15. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Differences between clinical and research practice in diagnosing borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1570-1574.

16. Magnavita JJ, Levy KN, Critchfield KL, et al. Ethical considerations in treatment of personality dysfunction: using evidence, principles, and clinical judgment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2010;41(1):64-74.

17. Zimmerman M. A review of 20 years of research on overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis in the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(2):71-79.

18. Westen D. Divergences between clinical and research methods for assessing personality disorders: implications for research and the evolution of axis II. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(7):895-903.

19. Zimmerman M. Diagnosing personality disorders: a review of issues and research methods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(3):225-245.

20. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenberg FR. Axis I phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1989;30(2):149-156.

21. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Axis I diagnostic comorbidity and borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(4):245-252.

22. Gunderson JG, Morey LC, Stout RL, et al. Major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder revisited: longitudinal interactions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1049-1056.

23. Bayes AJ, Parker GB. Clinical vs. DSM diagnosis of bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder and their co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;135(3):259-265.

24. Carpenter RW, Wood PK, Trull TJ. Comorbidity of borderline personality disorder and lifetime substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample. J Pers Disord. 2016;30(3):336-350.

25. Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, et al. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: a review and integration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20(2):235-253.

26. Matthies SD, Philipsen A. Common ground in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD)-review of recent findings. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2014;1:3.

27. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K, et al. Principal diagnoses in psychiatric outpatients with borderline personality disorder: implications for screening recommendations. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(1):54-60.

28. Magallón-Neri EM, Forns M, Canalda G, et al. Usefulness of the International Personality Disorder Examination Screening Questionnaire for borderline and impulsive personality pathology in adolescents. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(3):301-308.

29. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Langbehn DR, et al. The Iowa Personality Disorder Screen. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2010;26(1):11-18.

30. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord. 2003;17(6):568-573.

31. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Hodiamont PP. Results of the search for personality disorder screening tools: clinical implications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(2):165-173.

32. Hyler SE. Personality diagnostic questionnaire-4. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994.

33. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders - Patient edition (SCID-I/P, version 2.0). New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995.

34. Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, et al. The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology. 2009;42(1):32-39.

35. Poreh AM, Rawlings D, Claridge G, et al. The BPQ: a scale for the assessment of boderline personality based on DSM-IV criteria. J Pers Disord. 2006;20(3):247-260.

36. Ekselius L, Lindstrom E, von Knorring L, et al. SCID II interviews and the SCID Screen questionnaire as diagnostic tools for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(2):120-123.

37. Hyler SE, Skodol AE, Oldham JM, et al. Validity of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-Revised: a replication in an outpatient sample. Compr Psychiatry. 1992;33(2):73-77.

38. Davison S, Leese M, Taylor PJ. Examination of the screening properties of the personality diagnostic questionnaire 4+ (PDQ-4+) in a prison population. J Pers Disord. 2001;15(2):180-194.

39. Jacobsberg L, Perry S, Frances A. Diagnostic agreement between the SCID-II screening questionnaire and the Personality Disorder Examination. J Pers Assess. 1995;65(3):428-433.

40. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Masthoff ED, et al. Diagnostic efficiency among psychiatric outpatients of a self-report version of a subset of screen items of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Psychol Assess. 2010;22(4):945-952.

41. Lloyd C, Overall JE, Click M Jr. Screening for borderline personality disorders with the MMPI-168. J Clin Psychol. 1983;39(5):722-726.

42. Neal LA, Fox C, Carroll N, et al. Development and validation of a computerized screening test for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95(4):351-356.

43. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Moran P, et al. The Self-Report Standardized Assessment of Personality-abbreviated Scale: preliminary results of a brief screening test for personality disorders. Pers Ment Health. 2008;2(2):70-76.

44. Moran P, Leese M, Lee T, et al. Standardized Assessment of Personality - Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): preliminary validation of a brief screen for personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:228-232.

45. Chanen AM, Jovev M, Djaja D, et al. Screening for borderline personality disorder in outpatient youth. J Pers Disord. 2008;22(4):353-364.

46. van Alebeek A, van der Heijden PT, Hessels C, et al. Comparison of three questionnaires to screen for borderline personality disorder in adolescents and young adults. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2017:33;123-128.

47. Noblin JL, Venta A, Sharp C. The validity of the MSI-BPD among inpatient adolescents. Assessment. 2014;21(2):210-217.

48. Kröger C, Vonau M, Kliem S, et al. Emotion dysregulation as a core feature of borderline personality disorder: comparison of the discriminatory ability of two self-rating measures. Psychopathology. 2011;44(4):253-260.

49. Soler J, Domínguez-Clav E, García-Rizo C, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016;9(4):195-202.

50. Melartin T, Häkkinen M, Koivisto M, et al. Screening of psychiatric outpatients for borderline personality disorder with the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(6):475-479.

51. Zimmerman M. Misuse of the Mood Disorders Questionnaire as a case-finding measure and a critique of the concept of using a screening scale for bipolar disorder in psychiatric practice. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(2):127-134.

52. Zimmerman M. Screening for bipolar disorder: confusion between case-finding and screening. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(5):259-262.

53. Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993.

54. Koenigsberg HW, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, et al. Are the interpersonal and identity disturbances in the borderline personality disorder criteria linked to the traits of affective instability and impulsivity? J Pers Disord. 2001;15(4):358-370.

55. Grilo CM, Becker DF, Anez LM, et al. Diagnostic efficiency of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: an evaluation in Hispanic men and women with substance use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(1):126-131.

56. Korfine L, Hooley JM. Detecting individuals with borderline personality disorder in the community: an ascertainment strategy and comparison with a hospital sample. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(1):62-75.

57. Leppänen V, Lindeman S, Arntz A, et al. Preliminary evaluation of psychometric properties of the Finnish Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index: Oulu-BPD-Study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2013;67(5):312-319.

58. Pfohl B, Coryell W, Zimmerman M, et al. DSM-III personality disorders: diagnostic overlap and internal consistency of individual DSM-III criteria. Compr Psychiatry. 1986;27(1):22-34.

59. Reich J. Criteria for diagnosing DSM-III borderline personality disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1990;2(3):189-197.

60. Nurnberg HG, Raskin M, Levine PE, et al. Hierarchy of DSM-III-R criteria efficiency for the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 1991;5(3):211-224.

61. Farmer RF, Chapman AL. Evaluation of DSM-IV personality disorder criteria as assessed by the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(4):285-300.

62. Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, et al. Internal consistency, intercriterion overlap and diagnostic efficiency of criteria sets for DSM-IV schizotypal, borderline, avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(4):264-272.

63. Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Skodol AE, et al. Longitudinal diagnostic efficiency of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: a 2-year prospective study. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(6):357-362.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with impaired psychosocial functioning,1-4 reduced health-related quality of life,5 high utilization of services,6,7 and excess mortality.8-10 Although BPD occurs in up to 40% of psychiatric inpatients11 and 10% of outpatients,12 it is underrecognized.13-15 Often, patients with BPD do not receive an accurate diagnosis until ≥10 years after initially seeking treatment.16 The treatment and clinical implications of failing to recognize BPD include overprescribing medication and underutilizing empirically effective psychotherapies.14

This review summarizes studies of the underdiagnosis of BPD in routine clinical practice, describes which patients should be screened, and reviews alternative approaches to screening.

Underrecognition of BPD

The Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) project is an ongoing clinical research study involving the integration of research assessment methods into routine clinical practice.17 In an early report from the MIDAS project, BPD diagnoses derived from structured and unstructured clinical interviews were compared between 2 groups of psychiatric outpatients in the same practice.15 Individuals in the structured interview cohort were 35 times more often diagnosed with BPD than individuals evaluated with an unstructured clinical interview. Importantly, when the information from the structured interview was presented to the clinicians, BPD was more likely to be diagnosed clinically.

Other studies13,16 also found that the rate of diagnosing BPD was higher when the diagnosis was based on a semi-structured diagnostic interview compared with an unstructured clinical interview, and that clinicians were reluctant to diagnose BPD during their routine intake diagnostic evaluation.

Clinicians, however, do not use semi-structured interviews in their practice, and they also do not tend to diagnose personality disorders (PDs) based on direct questioning, as they typically would when assessing a symptom-based disorder such as depression or anxiety. Rather, clinicians report that they rely on longitudinal observations to diagnose PDs.18 However, the results from the MIDAS project were inconsistent with clinicians’ reports. When clinicians were presented with the results of the semi-structured interview, they usually would diagnose BPD, even though it was the initial evaluation. If clinicians actually relied on longitudinal observations and considered information based on the direct question approach of research interviews to be irrelevant or invalid, then the results from the semi-structured interview should not have influenced the rate at which they diagnosed BPD. This suggests that the primary issue in diagnosing PDs is not the need for longitudinal observation but rather the need for more information, and that there is a role for screening questionnaires.

One potential criticism of studies demonstrating underrecognition of BPD in clinical practice is that patients typically were interviewed when they presented for treatment, when most were depressed or anxious. The possible pathologizing effects of psychiatric state on personality have been known for years.19 However, a large body of literature examining the treatment, prognostic, familial, and biological correlates of PDs supports the validity of diagnosing PDs in this manner. Moreover, from a clinical perspective, the sooner a clinician is aware of the presence of BPD, the more likely this information can be used for treatment planning.

Who should be screened for BPD?

BPD is underrecognized and underdiagnosed because patients with BPD often also have comorbid mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders.20,21 The symptoms associated with these disorders are typically the chief concern of patients with undiagnosed BPD who present for treatment. Patients with BPD rarely present for an intake evaluation and state that they are struggling with abandonment fears, chronic feelings of emptiness, or an identity disturbance. If patients identified these problems as their chief concerns, BPD would be easier to recognize.

Although several studies have documented the frequency of BPD in patients with a specific psychiatric diagnosis such as major depressive disorder (MDD) or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,22-26 the MIDAS project examined the frequency of BPD in patients with various diagnoses and evaluated which disorders were associated with a significantly increased rate of BPD.27 The highest rate of BPD was found in patients with bipolar disorder. Approximately 25% of patients with bipolar II disorder and one-third of those with bipolar I disorder were diagnosed with BPD; these rates were significantly higher than the rate of BPD in patients without these disorders (Table 127). The rate of BPD was second highest in patients with a principal diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and MDD; however, the rate of BPD in these patients was not significantly elevated compared with patients who did not have these principal diagnoses. Three disorders were associated with a significantly lower rate of BPD: adjustment disorder, dysthymic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder.

It would be easy to recommend screening for BPD in all psychiatric patients. However, that is not feasible or practical. In making screening recommendations, absolute risk should be considered more important than relative risk. Clinicians should screen for BPD in patients presenting to a general psychiatric outpatient practice with a principal diagnosis of MDD, bipolar disorder, PTSD, or panic disorder with agoraphobia. That is, I recommend screening for BPD in patients with a principal diagnosis in which the prevalence of BPD is ≥10% (Table 127).

A brief review of screening statistics

Screening tests for most psychiatric disorders are based on multi-item scales in which a total score is computed from a sum of item scores, and a cutoff point is established to determine who does and does not screen positive on the test. However, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values are not invariant properties of a screening test with a continuous score distribution. Rather, the performance statistics of a scale can be altered by changing the threshold score to distinguish cases from non-cases. When the screening threshold is lowered, sensitivity increases and specificity decreases.

For screening, a broad net needs to be cast so that all (or almost all) cases are included. Therefore, the cutoff score should be set low to prioritize the sensitivity of the instrument. A screening scale also should have high negative predictive value so that the clinician can be confident that patients who screen negative on the test do not have the disorder.

Screening questionnaires for BPD

Several questionnaires have been developed to screen for PDs (Table 228-35). Some screen for each of the DSM PDs,28,36-42 and some screen more broadly for the presence or absence of any PD.29,43,44 The most commonly studied self-report scale for BPD is the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD),30 a 10-item self-report scale derived from a subset of questions from the BPD module of a semi-structured diagnostic interview.

The initial validation study30 found that the optimal cutoff score was 7, which resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 89%. Three studies have evaluated the scale in adolescents and young adults,45-47 and 3 studies examined the scale in adult outpatients.48-50 Across all 6 studies, at the optimal cutoff scores determined in each study, the sensitivity of the MSI-BPD ranged from 68% to 94% (mean, 80%) and the specificity ranged from 66% to 80% (mean, 72%).

Problems with screening questionnaires. Although screening scales have been developed for many psychiatric disorders, they have not been widely used in mental health settings. In a previous commentary, I argued that the conceptual justification for using self-report screening scales for single disorders in psychiatric settings is questionable.51 Another problem with screening scales is their potential misuse as case-finding instruments. In the literature on bipolar disorder screening, several researchers misconstrued a positive screen to indicate caseness.51 Although this is not a problem with the screening measures or the selection of a cutoff score, caution must be taken to not confuse screening with diagnosis.52

Screening for BPD as part of your diagnostic interview

An alternative approach to using self-administered questionnaires for screening is for clinicians to include questions in their evaluation as part of a psychiatric review of systems. When conducting a diagnostic interview, clinicians typically screen for disorders that are comorbid with the principal diagnosis by asking about the comorbid disorders’ necessary features or “gate criteria.” For example, in a patient with a principal diagnosis of MDD, the clinician would inquire about the presence of panic attacks, excessive worry, or substance use to screen for the presence of panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or a substance use disorder. In contrast, for polythetically defined disorders such as BPD, there is no single gate criterion, because the disorder is diagnosed based on the presence of at least 5 of 9 criteria and no single one of these criteria is required to be present to establish the diagnosis.

As part of the MIDAS project, the psychometric properties of the BPD criteria were examined to determine if it was possible to identify 1 or 2 criteria that could serve as gate criteria to screen for the disorder. If the sensitivity of 1 criterion or a combination of 2 BPD criteria was sufficiently high (ie, >90%), then the assessment of this criterion (or these criteria) could be included in a psychiatric review of systems, thus potentially improving the detection of BPD. Researchers hypothesized that affective instability, considered first by Linehan53 and later by other theorists54 to be of central importance to the clinical manifestations of BPD, could function as a gate criterion. In the sample of 3,674 psychiatric outpatients who were evaluated with a semi-structured interview, the sensitivity of the affective instability criterion was 92.8%, and the negative predictive value of the criterion was 99%.

Identifying a single BPD criterion that is present in the vast majority of patients diagnosed with BPD will allow clinicians to follow their usual clinical practice when conducting a psychiatric review of systems and inquire about the gate criteria of various disorders. Several studies have found that >90% of patients with BPD report affective instability. However, this does not mean that the diagnosis of BPD can be abbreviated to an assessment of the presence or absence of affective instability. Many patients who screen positive will not have BPD when a more definitive diagnostic evaluation is conducted. In the case of BPD, the more costly definitive diagnostic procedure simply entails inquiry of the other diagnostic criteria.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with impaired psychosocial functioning,1-4 reduced health-related quality of life,5 high utilization of services,6,7 and excess mortality.8-10 Although BPD occurs in up to 40% of psychiatric inpatients11 and 10% of outpatients,12 it is underrecognized.13-15 Often, patients with BPD do not receive an accurate diagnosis until ≥10 years after initially seeking treatment.16 The treatment and clinical implications of failing to recognize BPD include overprescribing medication and underutilizing empirically effective psychotherapies.14

This review summarizes studies of the underdiagnosis of BPD in routine clinical practice, describes which patients should be screened, and reviews alternative approaches to screening.

Underrecognition of BPD

The Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) project is an ongoing clinical research study involving the integration of research assessment methods into routine clinical practice.17 In an early report from the MIDAS project, BPD diagnoses derived from structured and unstructured clinical interviews were compared between 2 groups of psychiatric outpatients in the same practice.15 Individuals in the structured interview cohort were 35 times more often diagnosed with BPD than individuals evaluated with an unstructured clinical interview. Importantly, when the information from the structured interview was presented to the clinicians, BPD was more likely to be diagnosed clinically.

Other studies13,16 also found that the rate of diagnosing BPD was higher when the diagnosis was based on a semi-structured diagnostic interview compared with an unstructured clinical interview, and that clinicians were reluctant to diagnose BPD during their routine intake diagnostic evaluation.

Clinicians, however, do not use semi-structured interviews in their practice, and they also do not tend to diagnose personality disorders (PDs) based on direct questioning, as they typically would when assessing a symptom-based disorder such as depression or anxiety. Rather, clinicians report that they rely on longitudinal observations to diagnose PDs.18 However, the results from the MIDAS project were inconsistent with clinicians’ reports. When clinicians were presented with the results of the semi-structured interview, they usually would diagnose BPD, even though it was the initial evaluation. If clinicians actually relied on longitudinal observations and considered information based on the direct question approach of research interviews to be irrelevant or invalid, then the results from the semi-structured interview should not have influenced the rate at which they diagnosed BPD. This suggests that the primary issue in diagnosing PDs is not the need for longitudinal observation but rather the need for more information, and that there is a role for screening questionnaires.

One potential criticism of studies demonstrating underrecognition of BPD in clinical practice is that patients typically were interviewed when they presented for treatment, when most were depressed or anxious. The possible pathologizing effects of psychiatric state on personality have been known for years.19 However, a large body of literature examining the treatment, prognostic, familial, and biological correlates of PDs supports the validity of diagnosing PDs in this manner. Moreover, from a clinical perspective, the sooner a clinician is aware of the presence of BPD, the more likely this information can be used for treatment planning.

Who should be screened for BPD?

BPD is underrecognized and underdiagnosed because patients with BPD often also have comorbid mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders.20,21 The symptoms associated with these disorders are typically the chief concern of patients with undiagnosed BPD who present for treatment. Patients with BPD rarely present for an intake evaluation and state that they are struggling with abandonment fears, chronic feelings of emptiness, or an identity disturbance. If patients identified these problems as their chief concerns, BPD would be easier to recognize.

Although several studies have documented the frequency of BPD in patients with a specific psychiatric diagnosis such as major depressive disorder (MDD) or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,22-26 the MIDAS project examined the frequency of BPD in patients with various diagnoses and evaluated which disorders were associated with a significantly increased rate of BPD.27 The highest rate of BPD was found in patients with bipolar disorder. Approximately 25% of patients with bipolar II disorder and one-third of those with bipolar I disorder were diagnosed with BPD; these rates were significantly higher than the rate of BPD in patients without these disorders (Table 127). The rate of BPD was second highest in patients with a principal diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and MDD; however, the rate of BPD in these patients was not significantly elevated compared with patients who did not have these principal diagnoses. Three disorders were associated with a significantly lower rate of BPD: adjustment disorder, dysthymic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder.

It would be easy to recommend screening for BPD in all psychiatric patients. However, that is not feasible or practical. In making screening recommendations, absolute risk should be considered more important than relative risk. Clinicians should screen for BPD in patients presenting to a general psychiatric outpatient practice with a principal diagnosis of MDD, bipolar disorder, PTSD, or panic disorder with agoraphobia. That is, I recommend screening for BPD in patients with a principal diagnosis in which the prevalence of BPD is ≥10% (Table 127).

A brief review of screening statistics

Screening tests for most psychiatric disorders are based on multi-item scales in which a total score is computed from a sum of item scores, and a cutoff point is established to determine who does and does not screen positive on the test. However, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values are not invariant properties of a screening test with a continuous score distribution. Rather, the performance statistics of a scale can be altered by changing the threshold score to distinguish cases from non-cases. When the screening threshold is lowered, sensitivity increases and specificity decreases.

For screening, a broad net needs to be cast so that all (or almost all) cases are included. Therefore, the cutoff score should be set low to prioritize the sensitivity of the instrument. A screening scale also should have high negative predictive value so that the clinician can be confident that patients who screen negative on the test do not have the disorder.

Screening questionnaires for BPD

Several questionnaires have been developed to screen for PDs (Table 228-35). Some screen for each of the DSM PDs,28,36-42 and some screen more broadly for the presence or absence of any PD.29,43,44 The most commonly studied self-report scale for BPD is the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD),30 a 10-item self-report scale derived from a subset of questions from the BPD module of a semi-structured diagnostic interview.

The initial validation study30 found that the optimal cutoff score was 7, which resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 89%. Three studies have evaluated the scale in adolescents and young adults,45-47 and 3 studies examined the scale in adult outpatients.48-50 Across all 6 studies, at the optimal cutoff scores determined in each study, the sensitivity of the MSI-BPD ranged from 68% to 94% (mean, 80%) and the specificity ranged from 66% to 80% (mean, 72%).

Problems with screening questionnaires. Although screening scales have been developed for many psychiatric disorders, they have not been widely used in mental health settings. In a previous commentary, I argued that the conceptual justification for using self-report screening scales for single disorders in psychiatric settings is questionable.51 Another problem with screening scales is their potential misuse as case-finding instruments. In the literature on bipolar disorder screening, several researchers misconstrued a positive screen to indicate caseness.51 Although this is not a problem with the screening measures or the selection of a cutoff score, caution must be taken to not confuse screening with diagnosis.52

Screening for BPD as part of your diagnostic interview

An alternative approach to using self-administered questionnaires for screening is for clinicians to include questions in their evaluation as part of a psychiatric review of systems. When conducting a diagnostic interview, clinicians typically screen for disorders that are comorbid with the principal diagnosis by asking about the comorbid disorders’ necessary features or “gate criteria.” For example, in a patient with a principal diagnosis of MDD, the clinician would inquire about the presence of panic attacks, excessive worry, or substance use to screen for the presence of panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or a substance use disorder. In contrast, for polythetically defined disorders such as BPD, there is no single gate criterion, because the disorder is diagnosed based on the presence of at least 5 of 9 criteria and no single one of these criteria is required to be present to establish the diagnosis.

As part of the MIDAS project, the psychometric properties of the BPD criteria were examined to determine if it was possible to identify 1 or 2 criteria that could serve as gate criteria to screen for the disorder. If the sensitivity of 1 criterion or a combination of 2 BPD criteria was sufficiently high (ie, >90%), then the assessment of this criterion (or these criteria) could be included in a psychiatric review of systems, thus potentially improving the detection of BPD. Researchers hypothesized that affective instability, considered first by Linehan53 and later by other theorists54 to be of central importance to the clinical manifestations of BPD, could function as a gate criterion. In the sample of 3,674 psychiatric outpatients who were evaluated with a semi-structured interview, the sensitivity of the affective instability criterion was 92.8%, and the negative predictive value of the criterion was 99%.

Identifying a single BPD criterion that is present in the vast majority of patients diagnosed with BPD will allow clinicians to follow their usual clinical practice when conducting a psychiatric review of systems and inquire about the gate criteria of various disorders. Several studies have found that >90% of patients with BPD report affective instability. However, this does not mean that the diagnosis of BPD can be abbreviated to an assessment of the presence or absence of affective instability. Many patients who screen positive will not have BPD when a more definitive diagnostic evaluation is conducted. In the case of BPD, the more costly definitive diagnostic procedure simply entails inquiry of the other diagnostic criteria.

1. Bellino S, Patria L, Paradiso E, et al. Major depression in patients with borderline personality disorder: a clinical investigation. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(4):234-238.

2. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):276-283.

3. Gunderson JG, Stout RL, McGlashan TH, et al. Ten-year course of borderline personality disorder: psychopathology and function from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):827-837.

4. Zanarini MC, Jacoby RJ, Frankenburg FR, et al. The 10-year course of social security disability income reported by patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(4):346-356.

5. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533-545.

6. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):295-302.

7. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al. Mental health service utilization by borderline personality disorder patients and Axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for 6 years. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(1):28-36.

8. Pompili M, Girardi P, Ruberto A, et al. Suicide in borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Nord J Psychiatry. 2005;59(5):319-324.

9. Oldham JM. Borderline personality disorder and suicidality. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):20-26.

10. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(3):226-239.

11. Marinangeli M, Butti G, Scinto A, et al. Patterns of comorbidity among DSM-III-R personality disorders. Psychopathology. 2000;33(2):69-74.

12. Zimmerman M, Rothschild L, Chelminski I. The frequency of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1911-1918.

13. Comtois KA, Carmel A. Borderline personality disorder and high utilization of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization: concordance between research and clinical diagnosis. J Behav Health Servi Res. 2016;43(2):272-280.

14. Paris J, Black DW. Borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder: what is the difference and why does it matter? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(1):3-7.

15. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Differences between clinical and research practice in diagnosing borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1570-1574.

16. Magnavita JJ, Levy KN, Critchfield KL, et al. Ethical considerations in treatment of personality dysfunction: using evidence, principles, and clinical judgment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2010;41(1):64-74.

17. Zimmerman M. A review of 20 years of research on overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis in the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(2):71-79.

18. Westen D. Divergences between clinical and research methods for assessing personality disorders: implications for research and the evolution of axis II. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(7):895-903.

19. Zimmerman M. Diagnosing personality disorders: a review of issues and research methods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(3):225-245.

20. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenberg FR. Axis I phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1989;30(2):149-156.

21. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Axis I diagnostic comorbidity and borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(4):245-252.

22. Gunderson JG, Morey LC, Stout RL, et al. Major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder revisited: longitudinal interactions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1049-1056.

23. Bayes AJ, Parker GB. Clinical vs. DSM diagnosis of bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder and their co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;135(3):259-265.

24. Carpenter RW, Wood PK, Trull TJ. Comorbidity of borderline personality disorder and lifetime substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample. J Pers Disord. 2016;30(3):336-350.

25. Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, et al. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: a review and integration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20(2):235-253.

26. Matthies SD, Philipsen A. Common ground in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD)-review of recent findings. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2014;1:3.

27. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K, et al. Principal diagnoses in psychiatric outpatients with borderline personality disorder: implications for screening recommendations. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(1):54-60.

28. Magallón-Neri EM, Forns M, Canalda G, et al. Usefulness of the International Personality Disorder Examination Screening Questionnaire for borderline and impulsive personality pathology in adolescents. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(3):301-308.

29. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Langbehn DR, et al. The Iowa Personality Disorder Screen. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2010;26(1):11-18.

30. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord. 2003;17(6):568-573.

31. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Hodiamont PP. Results of the search for personality disorder screening tools: clinical implications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(2):165-173.

32. Hyler SE. Personality diagnostic questionnaire-4. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994.

33. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders - Patient edition (SCID-I/P, version 2.0). New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995.

34. Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, et al. The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology. 2009;42(1):32-39.

35. Poreh AM, Rawlings D, Claridge G, et al. The BPQ: a scale for the assessment of boderline personality based on DSM-IV criteria. J Pers Disord. 2006;20(3):247-260.

36. Ekselius L, Lindstrom E, von Knorring L, et al. SCID II interviews and the SCID Screen questionnaire as diagnostic tools for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(2):120-123.

37. Hyler SE, Skodol AE, Oldham JM, et al. Validity of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-Revised: a replication in an outpatient sample. Compr Psychiatry. 1992;33(2):73-77.

38. Davison S, Leese M, Taylor PJ. Examination of the screening properties of the personality diagnostic questionnaire 4+ (PDQ-4+) in a prison population. J Pers Disord. 2001;15(2):180-194.

39. Jacobsberg L, Perry S, Frances A. Diagnostic agreement between the SCID-II screening questionnaire and the Personality Disorder Examination. J Pers Assess. 1995;65(3):428-433.

40. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Masthoff ED, et al. Diagnostic efficiency among psychiatric outpatients of a self-report version of a subset of screen items of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Psychol Assess. 2010;22(4):945-952.

41. Lloyd C, Overall JE, Click M Jr. Screening for borderline personality disorders with the MMPI-168. J Clin Psychol. 1983;39(5):722-726.

42. Neal LA, Fox C, Carroll N, et al. Development and validation of a computerized screening test for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95(4):351-356.

43. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Moran P, et al. The Self-Report Standardized Assessment of Personality-abbreviated Scale: preliminary results of a brief screening test for personality disorders. Pers Ment Health. 2008;2(2):70-76.

44. Moran P, Leese M, Lee T, et al. Standardized Assessment of Personality - Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): preliminary validation of a brief screen for personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:228-232.

45. Chanen AM, Jovev M, Djaja D, et al. Screening for borderline personality disorder in outpatient youth. J Pers Disord. 2008;22(4):353-364.

46. van Alebeek A, van der Heijden PT, Hessels C, et al. Comparison of three questionnaires to screen for borderline personality disorder in adolescents and young adults. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2017:33;123-128.

47. Noblin JL, Venta A, Sharp C. The validity of the MSI-BPD among inpatient adolescents. Assessment. 2014;21(2):210-217.

48. Kröger C, Vonau M, Kliem S, et al. Emotion dysregulation as a core feature of borderline personality disorder: comparison of the discriminatory ability of two self-rating measures. Psychopathology. 2011;44(4):253-260.

49. Soler J, Domínguez-Clav E, García-Rizo C, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016;9(4):195-202.

50. Melartin T, Häkkinen M, Koivisto M, et al. Screening of psychiatric outpatients for borderline personality disorder with the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(6):475-479.

51. Zimmerman M. Misuse of the Mood Disorders Questionnaire as a case-finding measure and a critique of the concept of using a screening scale for bipolar disorder in psychiatric practice. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(2):127-134.

52. Zimmerman M. Screening for bipolar disorder: confusion between case-finding and screening. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(5):259-262.

53. Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993.

54. Koenigsberg HW, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, et al. Are the interpersonal and identity disturbances in the borderline personality disorder criteria linked to the traits of affective instability and impulsivity? J Pers Disord. 2001;15(4):358-370.

55. Grilo CM, Becker DF, Anez LM, et al. Diagnostic efficiency of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: an evaluation in Hispanic men and women with substance use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(1):126-131.

56. Korfine L, Hooley JM. Detecting individuals with borderline personality disorder in the community: an ascertainment strategy and comparison with a hospital sample. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(1):62-75.

57. Leppänen V, Lindeman S, Arntz A, et al. Preliminary evaluation of psychometric properties of the Finnish Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index: Oulu-BPD-Study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2013;67(5):312-319.

58. Pfohl B, Coryell W, Zimmerman M, et al. DSM-III personality disorders: diagnostic overlap and internal consistency of individual DSM-III criteria. Compr Psychiatry. 1986;27(1):22-34.

59. Reich J. Criteria for diagnosing DSM-III borderline personality disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1990;2(3):189-197.

60. Nurnberg HG, Raskin M, Levine PE, et al. Hierarchy of DSM-III-R criteria efficiency for the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 1991;5(3):211-224.

61. Farmer RF, Chapman AL. Evaluation of DSM-IV personality disorder criteria as assessed by the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(4):285-300.

62. Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, et al. Internal consistency, intercriterion overlap and diagnostic efficiency of criteria sets for DSM-IV schizotypal, borderline, avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(4):264-272.

63. Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Skodol AE, et al. Longitudinal diagnostic efficiency of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: a 2-year prospective study. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(6):357-362.

1. Bellino S, Patria L, Paradiso E, et al. Major depression in patients with borderline personality disorder: a clinical investigation. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(4):234-238.

2. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):276-283.

3. Gunderson JG, Stout RL, McGlashan TH, et al. Ten-year course of borderline personality disorder: psychopathology and function from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):827-837.

4. Zanarini MC, Jacoby RJ, Frankenburg FR, et al. The 10-year course of social security disability income reported by patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(4):346-356.

5. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533-545.

6. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):295-302.

7. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al. Mental health service utilization by borderline personality disorder patients and Axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for 6 years. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(1):28-36.

8. Pompili M, Girardi P, Ruberto A, et al. Suicide in borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Nord J Psychiatry. 2005;59(5):319-324.

9. Oldham JM. Borderline personality disorder and suicidality. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):20-26.

10. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(3):226-239.

11. Marinangeli M, Butti G, Scinto A, et al. Patterns of comorbidity among DSM-III-R personality disorders. Psychopathology. 2000;33(2):69-74.

12. Zimmerman M, Rothschild L, Chelminski I. The frequency of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1911-1918.

13. Comtois KA, Carmel A. Borderline personality disorder and high utilization of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization: concordance between research and clinical diagnosis. J Behav Health Servi Res. 2016;43(2):272-280.

14. Paris J, Black DW. Borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder: what is the difference and why does it matter? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(1):3-7.

15. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Differences between clinical and research practice in diagnosing borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1570-1574.

16. Magnavita JJ, Levy KN, Critchfield KL, et al. Ethical considerations in treatment of personality dysfunction: using evidence, principles, and clinical judgment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2010;41(1):64-74.

17. Zimmerman M. A review of 20 years of research on overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis in the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(2):71-79.

18. Westen D. Divergences between clinical and research methods for assessing personality disorders: implications for research and the evolution of axis II. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(7):895-903.

19. Zimmerman M. Diagnosing personality disorders: a review of issues and research methods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(3):225-245.

20. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenberg FR. Axis I phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1989;30(2):149-156.

21. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Axis I diagnostic comorbidity and borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(4):245-252.

22. Gunderson JG, Morey LC, Stout RL, et al. Major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder revisited: longitudinal interactions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1049-1056.

23. Bayes AJ, Parker GB. Clinical vs. DSM diagnosis of bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder and their co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;135(3):259-265.

24. Carpenter RW, Wood PK, Trull TJ. Comorbidity of borderline personality disorder and lifetime substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample. J Pers Disord. 2016;30(3):336-350.

25. Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, et al. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: a review and integration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20(2):235-253.

26. Matthies SD, Philipsen A. Common ground in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD)-review of recent findings. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2014;1:3.

27. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K, et al. Principal diagnoses in psychiatric outpatients with borderline personality disorder: implications for screening recommendations. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(1):54-60.

28. Magallón-Neri EM, Forns M, Canalda G, et al. Usefulness of the International Personality Disorder Examination Screening Questionnaire for borderline and impulsive personality pathology in adolescents. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(3):301-308.

29. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Langbehn DR, et al. The Iowa Personality Disorder Screen. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2010;26(1):11-18.

30. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord. 2003;17(6):568-573.

31. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Hodiamont PP. Results of the search for personality disorder screening tools: clinical implications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(2):165-173.

32. Hyler SE. Personality diagnostic questionnaire-4. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994.

33. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders - Patient edition (SCID-I/P, version 2.0). New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995.

34. Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, et al. The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology. 2009;42(1):32-39.

35. Poreh AM, Rawlings D, Claridge G, et al. The BPQ: a scale for the assessment of boderline personality based on DSM-IV criteria. J Pers Disord. 2006;20(3):247-260.

36. Ekselius L, Lindstrom E, von Knorring L, et al. SCID II interviews and the SCID Screen questionnaire as diagnostic tools for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(2):120-123.

37. Hyler SE, Skodol AE, Oldham JM, et al. Validity of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-Revised: a replication in an outpatient sample. Compr Psychiatry. 1992;33(2):73-77.

38. Davison S, Leese M, Taylor PJ. Examination of the screening properties of the personality diagnostic questionnaire 4+ (PDQ-4+) in a prison population. J Pers Disord. 2001;15(2):180-194.

39. Jacobsberg L, Perry S, Frances A. Diagnostic agreement between the SCID-II screening questionnaire and the Personality Disorder Examination. J Pers Assess. 1995;65(3):428-433.

40. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Masthoff ED, et al. Diagnostic efficiency among psychiatric outpatients of a self-report version of a subset of screen items of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Psychol Assess. 2010;22(4):945-952.

41. Lloyd C, Overall JE, Click M Jr. Screening for borderline personality disorders with the MMPI-168. J Clin Psychol. 1983;39(5):722-726.

42. Neal LA, Fox C, Carroll N, et al. Development and validation of a computerized screening test for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95(4):351-356.

43. Germans S, Van Heck GL, Moran P, et al. The Self-Report Standardized Assessment of Personality-abbreviated Scale: preliminary results of a brief screening test for personality disorders. Pers Ment Health. 2008;2(2):70-76.

44. Moran P, Leese M, Lee T, et al. Standardized Assessment of Personality - Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): preliminary validation of a brief screen for personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:228-232.

45. Chanen AM, Jovev M, Djaja D, et al. Screening for borderline personality disorder in outpatient youth. J Pers Disord. 2008;22(4):353-364.

46. van Alebeek A, van der Heijden PT, Hessels C, et al. Comparison of three questionnaires to screen for borderline personality disorder in adolescents and young adults. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2017:33;123-128.

47. Noblin JL, Venta A, Sharp C. The validity of the MSI-BPD among inpatient adolescents. Assessment. 2014;21(2):210-217.

48. Kröger C, Vonau M, Kliem S, et al. Emotion dysregulation as a core feature of borderline personality disorder: comparison of the discriminatory ability of two self-rating measures. Psychopathology. 2011;44(4):253-260.

49. Soler J, Domínguez-Clav E, García-Rizo C, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016;9(4):195-202.

50. Melartin T, Häkkinen M, Koivisto M, et al. Screening of psychiatric outpatients for borderline personality disorder with the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(6):475-479.

51. Zimmerman M. Misuse of the Mood Disorders Questionnaire as a case-finding measure and a critique of the concept of using a screening scale for bipolar disorder in psychiatric practice. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(2):127-134.

52. Zimmerman M. Screening for bipolar disorder: confusion between case-finding and screening. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(5):259-262.

53. Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993.

54. Koenigsberg HW, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, et al. Are the interpersonal and identity disturbances in the borderline personality disorder criteria linked to the traits of affective instability and impulsivity? J Pers Disord. 2001;15(4):358-370.

55. Grilo CM, Becker DF, Anez LM, et al. Diagnostic efficiency of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: an evaluation in Hispanic men and women with substance use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(1):126-131.

56. Korfine L, Hooley JM. Detecting individuals with borderline personality disorder in the community: an ascertainment strategy and comparison with a hospital sample. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(1):62-75.

57. Leppänen V, Lindeman S, Arntz A, et al. Preliminary evaluation of psychometric properties of the Finnish Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index: Oulu-BPD-Study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2013;67(5):312-319.

58. Pfohl B, Coryell W, Zimmerman M, et al. DSM-III personality disorders: diagnostic overlap and internal consistency of individual DSM-III criteria. Compr Psychiatry. 1986;27(1):22-34.

59. Reich J. Criteria for diagnosing DSM-III borderline personality disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1990;2(3):189-197.

60. Nurnberg HG, Raskin M, Levine PE, et al. Hierarchy of DSM-III-R criteria efficiency for the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 1991;5(3):211-224.

61. Farmer RF, Chapman AL. Evaluation of DSM-IV personality disorder criteria as assessed by the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(4):285-300.

62. Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, et al. Internal consistency, intercriterion overlap and diagnostic efficiency of criteria sets for DSM-IV schizotypal, borderline, avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(4):264-272.

63. Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Skodol AE, et al. Longitudinal diagnostic efficiency of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: a 2-year prospective study. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(6):357-362.